Abstract

Adults perform better than juveniles in food-seeking tasks. Using the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans to probe the neural mechanisms underlying behavioral maturation, we found that adults and juveniles require different combinations of sensory neurons to generate age-specific food-seeking behavior. We first show that adults and juveniles differ in their response to and preference for food-associated odors, and we analyze genetic mutants to map the neuronal circuits required for those behavioral responses. We developed a novel device to trap juveniles and record their neuronal activity. Activity measurements revealed that adult and juvenile AWA sensory neurons respond to the addition of diacetyl stimulus, whereas AWB, ASK, and AWC sensory neurons encode its removal specifically in adults. Further, we show that reducing neurotransmission from the additional AWB, ASK, and AWC sensory neurons transforms odor preferences from an adult to a juvenile-like state. We also show that AWB and ASK neurons drive behavioral changes exclusively in adults, providing more evidence that age-specific circuits drive age-specific behavior. Collectively, our results show that an odor-evoked sensory code is modified during the juvenile-to-adult transition in animal development to drive age-appropriate behavior. We suggest that this altered sensory code specifically enables adults to extract additional stimulus features and generate robust behavior.

Keywords: behavior, chemotaxis, development, neural circuits, sensory code

Significance Statement

How does mature behavior arise during development? We use the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, to probe this question at the level of sensory neural circuits. Interestingly, despite having the same sets of sensory neurons, juveniles are worse than adults at seeking food. We found that adults use more neurons than juveniles to drive food-seeking behavior. We confirm the requirement for additional sensory neurons in the adult using functional imaging. Further, we show that these additional neurons participate exclusively in adults, and that blocking neurotransmission from these neurons transforms adult odor preferences to a juvenile-like state. We speculate that adults acquire additional features for a given food stimulus that allows them to find food more efficiently.

Introduction

In most animals, adults and juveniles have large differences in their behavioral repertoire. For example, adult humans process social information differently than their adolescent counterparts (Blakemore 2008). Although imaging and behavioral studies in humans have suggested that the adolescent brain is plastic (Fuhrmann et al., 2015), less is known about the mechanisms driving this plasticity. Animal models, particularly hamsters, have been used to show that while juveniles and adults both detect social cues, they differ in their behavioral responses to those cues (Romeo et al., 1998; Petrulis 2009; Schulz et al., 2009). Additional studies have shown that adults and juveniles use different brain regions to process social cues, suggesting that differences in regional processing might explain the behavioral differences (Bell et al., 2013). However, the neural mechanisms that drive the differences between adult and juvenile behaviors remain poorly understood.

Work in nonmodel mammalian systems has attempted to understand the role of developmental behavioral differences at the level of sensory encoding and perception (Sarro et al., 2011). In particular, juvenile gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) exhibit neural sensitivity that is superior to their behavioral threshold, suggesting that the capacity for robust behavior exists but is not executed in immature animals (Sarro et al., 2011). Here, we establish the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a genetically tractable model for understanding the mechanisms driving behavioral maturation during development. C. elegans is an ideal model for decoding developmental plasticity: its cellular lineage (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977; Sulston et al., 1983) and neuronal connectome (White et al., 1986) are fully mapped. Additionally, it undergoes a stereotyped developmental program that includes four juvenile larval stages (L1, L2, L3, and L4) separated by individual molts before reaching adulthood (Brenner, 1974). This rigorously executed developmental program provides well-defined stages that enable easier characterization of age-specific food-seeking behavior (Ward, 1973). In addition, developmental plasticity in the C. elegans system has been previously characterized. The C. elegans life cycle is regulated by environment; when juveniles, but not adults, are exposed to unfavorable conditions, they enter an alternate dauer diapause stage (Golden and Riddle, 1982, 1984). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that exposing C. elegans juveniles to stress affects both gene expression and behavior in adults (Hall et al., 2010; Sims et al., 2016). These results demonstrate that C. elegans exhibit age-specific behaviors that are subject to environmental influences and suggest that C. elegans is ideal for uncovering cellular-level mechanisms of behavioral maturation.

We focused our analysis on the maturation of food-seeking behavior, where adults are shown to have robust and quantitative readouts (Ward, 1973; Bargmann, 2006; Albrecht and Bargmann, 2011). Moreover, the sensory neurons driving these behaviors have also been mapped using cell ablations. The AWA chemosensory neurons are required for attraction to the food odor diacetyl (Bargmann et al., 1993; Larsch et al., 2015), while AWC neurons drive attraction to isoamyl alcohol, benzaldehyde, and 2,3-pentanedione (Bargmann et al., 1993; Wes and Bargmann, 2001, Bargmann, 2006). By contrast, AWB neurons drive repulsion from the volatile repellent, 2-nonanone (Troemel et al., 1997). When we examined food-seeking behavior in juveniles, we discovered that juveniles, compared with adults, have reduced attraction to the food-associated odor diacetyl and altered odor preferences. We show that both adults and juveniles detect diacetyl odor, but that adults use additional sensory neurons to encode diacetyl information. Further, we find that altering neurotransmission from the additional neurons can attenuate adult attraction to diacetyl and transform adults to a juvenile-like odor preference, linking changes in odor code to behavior. Our results highlight how the diacetyl odor code is altered during development and suggest that neurotransmitter pathways play a crucial role in generating plasticity in sensory neurons during maturation.

Materials and Methods

Odor chemotaxis

We conducted hatch-offs to obtain synchronously staged worms for behavioral analysis. Briefly, we placed 40–50 adults on 10-cm NGM agar plates seeded with an Escherichia coli OP50 lawn and allowed them to lay eggs for 2–3 h. The adults were removed, and egg-covered plates were incubated at 20°C for 48 h for L3 and 96 h for adult day 1 hermaphrodites.

Chemotaxis assays on square plates (Troemel et al., 1997) were conducted for 1 h at room temperature as previously described (Leinwand et al., 2015). Briefly, assay plates were poured using 11 ml of 1.6% agar solution containing 5 mm KPO4 (pH 6), 1 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm MgSO4. Animals were washed once in M9+MgSO4 followed by three washes in chemotaxis assay buffer (5 mm KPO4, 1 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm MgSO4). We used the following odors diluted in ethanol: (1) 2,3-butanedione (diacetyl; Sigma-Aldrich cat. # 11038), (2) benzaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich cat. # 418099), (3) 2,3-pentanedione (Sigma-Aldrich cat. # 241962), (4) 2-nonanone (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. # 108731), and (5) pyrazine (Sigma-Aldrich cat. # P56003-10G) as indicated. Average chemotaxis index from six or more assays performed over at least three different days are shown.

Diacetyl preference assays were conducted as described by Fujiwara et al. (2016). Two-tailed, unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA were used to compare the responses of different genotypes or stages. Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied when appropriate. Source data and associated p-values for all behavior experiments are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Raw data for chemotaxis and preference assays

| Strain | Stage | Assay | Odor and concentration (%) | A + B or (total odor responders) | E + F or (total control responders) | A + B + C + D + E + F or (total responders) | CI or PI | SEM | Total plates (n) | Figure | p–value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 1 | 1548 | 71 | 1691 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 17 | Fig. 1B* | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 1 | 1158 | 182 | 1641 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 19 | Fig. 1B* | 2.31E–08 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.2 | 1383 | 77 | 1486 | 0.88 | 0.04 | 13 | Fig. 1B | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.2 | 1325 | 335 | 1954 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 11 | Fig. 1B | 5.61E–06 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 5901 | 638 | 6748 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 61 | Fig. 1B* | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 4579 | 1318 | 7258 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 51 | Fig. 1B* | 4.03E–19 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.05 | 1243 | 216 | 1505 | 0.68 | 0.04 | 14 | Fig. 1B | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.05 | 688 | 368 | 1316 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 10 | Fig. 1B | 2.80E–05 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.02 | 974 | 263 | 1294 | 0.55 | 0.08 | 12 | Fig. 1B | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.02 | 982 | 647 | 2065 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 12 | Fig. 1B | 2.18E–04 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 4144 | 1476 | 6040 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 51 | Fig. 1B | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 3549 | 2315 | 7729 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 55 | Fig. 1B | 1.28E–12 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.001 | 484 | 503 | 1197 | –0.02 | 0.07 | 10 | Fig. 1B | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.001 | 389 | 374 | 1064 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 11 | Fig. 1B | 0.51 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | IAA 100 | 1117 | 16 | 1200 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 10 | Fig. 1C | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | IAA 100 | 764 | 52 | 997 | 0.71 | 0.03 | 9 | Fig. 1C | 2.21E–05 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | IAA 0.1 | 1784 | 97 | 1940 | 0.87 | 0.03 | 17 | Fig. 1C | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | IAA 0.1 | 1111 | 119 | 1381 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 1C | 3.42E–03 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | IAA 0.01 | 768 | 213 | 1012 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 9 | Fig. 1C | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | IAA 0.01 | 776 | 485 | 1581 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 9 | Fig. 1C | 0.01 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | BZ 0.1 | 1575 | 333 | 1947 | 0.64 | 0.04 | 17 | Fig. 1D | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | BZ 0.1 | 1138 | 402 | 1843 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 15 | Fig. 1D | 5.32E–04 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | BZ 0.01 | 1834 | 1000 | 3058 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 26 | Fig. 1D | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | BZ 0.01 | 778 | 688 | 2164 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 17 | Fig. 1D | 3.73E–06 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | PENT 0.1 | 838 | 10 | 862 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 7 | Fig. 1E | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | PENT 0.1 | 903 | 34 | 1029 | 0.84 | 0.03 | 6 | Fig. 1E | 0.01 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | PENT 0.01 | 633 | 66 | 720 | 0.79 | 0.04 | 6 | Fig. 1E | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | PENT 0.01 | 1198 | 355 | 2023 | 0.42 | 0.08 | 8 | Fig. 1E | 3.28E–03 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | NON 10 | 858 | 1516 | 2790 | –0.24 | 0.06 | 23 | Fig. 1F | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | NON 10 | 679 | 1601 | 2974 | –0.31 | 0.05 | 20 | Fig. 1F | 0.26 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | NON 2 | 433 | 492 | 1013 | –0.06 | 0.06 | 10 | Fig. 1F | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | NON 2 | 558 | 910 | 1946 | –0.18 | 0.07 | 10 | Fig. 1F | 0.14 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | NON 1 | 686 | 896 | 1738 | –0.12 | 0.06 | 14 | Fig. 1F | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | NON 1 | 530 | 785 | 1779 | –0.14 | 0.05 | 12 | Fig. 1F | 0.80 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | BZ 100 | 12 | 676 | 919 | –0.72 | 0.04 | 9 | Fig. 1G | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | BZ 100 | 8 | 782 | 1084 | –0.71 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 1G | 0.81 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 100 | 300 | 1177 | 1859 | –0.47 | 0.05 | 19 | Fig. 1H* | — |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 100 | 259 | 510 | 1120 | –0.22 | 0.03 | 13 | Fig. 1H* | 3.21E–05 |

| N2 | Adult | Preference | DAC 0.1, PYR 0.8mg/ml | 1222 (DAC) | 761 (PYR) | 1983 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 14 | Fig. 1J* | — |

| N2 | L3 | Preference | DAC 0.1, PYR 0.8mg/ml | 164 (DAC) | 681 (PYR) | 845 | –0.61 | 0.04 | 12 | Fig. 1J* | 3.21E–12 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 3826 | 1204 | 5418 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 46 | Fig. 2A | — |

| AWA- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 768 | 637 | 1541 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 12 | Fig. 2A | <0.05 |

| AWB- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 953 | 492 | 1620 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 11 | Fig. 2A | <0.05 |

| AWC- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 921 | 257 | 1290 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 11 | Fig. 2A | >0.05 |

| ASE- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 1151 | 409 | 1614 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 12 | Fig. 2A | >0.05 |

| ASH- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 750 | 276 | 1142 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 11 | Fig. 2A | >0.05 |

| ASK- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 771 | 430 | 1276 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 10 | Fig. 2A | <0.05 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 3253 | 1916 | 6859 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 48 | Fig. 2A | — |

| AWA- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 340 | 393 | 997 | –0.05 | 0.05 | 10 | Fig. 2A | <0.05 |

| AWB- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 812 | 470 | 1769 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 13 | Fig. 2A | >0.05 |

| AWC- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 874 | 495 | 1748 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 2A | >0.05 |

| ASE- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 887 | 421 | 1603 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 14 | Fig. 2A | >0.05 |

| ASH- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 582 | 401 | 1329 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 2A | >0.05 |

| ASK- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 494 | 391 | 1141 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 12 | Fig. 2A | >0.05 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 5901 | 638 | 6748 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 61 | Fig. 2C* | — |

| AWA- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 490 | 491 | 1096 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 2C | <0.05 |

| AWB- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 949 | 85 | 1064 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 2C | >0.05 |

| AWC- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1391 | 112 | 1566 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 12 | Fig. 2C | >0.05 |

| ASE- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1079 | 125 | 1224 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 10 | Fig. 2C | >0.05 |

| ASH- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 964 | 95 | 1108 | 0.78 | 0.05 | 10 | Fig. 2C | >0.05 |

| ASK- | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 909 | 242 | 1195 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 11 | Fig. 2C | <0.05 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 4579 | 1318 | 7258 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 51 | Fig. 2C | — |

| AWA- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 423 | 419 | 1191 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 2C | <0.05 |

| AWB- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 910 | 193 | 1428 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 13 | Fig. 2C | >0.05 |

| AWC- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1223 | 247 | 1804 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 2C | >0.05 |

| ASE- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1640 | 345 | 2278 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 16 | Fig. 2C | <0.05 |

| ASH- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1099 | 227 | 1682 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 11 | Fig. 2C | >0.05 |

| ASK- | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 668 | 253 | 1087 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 10 | Fig. 2C | >0.05 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 1 | 1548 | 71 | 1691 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 17 | Fig. 2E* | — |

| AWA- | Adult | SPC | DAC 1 | 975 | 253 | 1369 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 12 | Fig. 2E | <0.05 |

| AWB- | Adult | SPC | DAC 1 | 1259 | 45 | 1417 | 0.86 | 0.01 | 12 | Fig. 2E | >0.05 |

| AWC- | Adult | SPC | DAC 1 | 642 | 58 | 792 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 10 | Fig. 2E | >0.05 |

| ASE- | Adult | SPC | DAC 1 | 893 | 22 | 931 | 0.94 | 0.02 | 10 | Fig. 2E | >0.05 |

| ASH- | Adult | SPC | DAC 1 | 805 | 24 | 866 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 10 | Fig. 2E | >0.05 |

| ASK- | Adult | SPC | DAC 1 | 808 | 115 | 953 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 12 | Fig. 2E | >0.05 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 1 | 1158 | 182 | 1641 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 19 | Fig. 2E* | — |

| AWA- | L3 | SPC | DAC 1 | 1597 | 539 | 2611 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 15 | Fig. 2E | <0.05 |

| AWB- | L3 | SPC | DAC 1 | 848 | 94 | 1130 | 0.67 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 2E | >0.05 |

| AWC- | L3 | SPC | DAC 1 | 818 | 124 | 1256 | 0.55 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 2E | >0.05 |

| ASE- | L3 | SPC | DAC 1 | 1131 | 72 | 1251 | 0.85 | 0.02 | 11 | Fig. 2E | <0.05 |

| ASH- | L3 | SPC | DAC 1 | 715 | 47 | 920 | 0.73 | 0.03 | 11 | Fig. 2E | >0.05 |

| ASK- | L3 | SPC | DAC 1 | 911 | 185 | 1364 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 12 | Fig. 2E | >0.05 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 100 | 300 | 1177 | 1859 | –0.47 | 0.05 | 19 | Fig.2-1B* | — |

| AWA- | Adult | SPC | DAC 100 | 239 | 758 | 1115 | –0.47 | 0.11 | 10 | Fig. 2-1A | >0.05 |

| AWB- | Adult | SPC | DAC 100 | 187 | 625 | 1007 | –0.43 | 0.07 | 11 | Fig. 2-1B | >0.05 |

| AWC- | Adult | SPC | DAC 100 | 115 | 893 | 1324 | –0.59 | 0.05 | 14 | Fig. 2-1B | >0.05 |

| ASE- | Adult | SPC | DAC 100 | 301 | 660 | 1117 | –0.32 | 0.07 | 10 | Fig. 2-1B | >0.05 |

| ASH- | Adult | SPC | DAC 100 | 320 | 272 | 751 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 10 | Fig. 2-1B | <0.05 |

| ASK- | Adult | SPC | DAC 100 | 90 | 703 | 852 | –0.72 | 0.07 | 10 | Fig. 2-1B | >0.05 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 100 | 259 | 510 | 1120 | –0.22 | 0.03 | 13 | Fig.2-1B* | — |

| AWA- | L3 | SPC | DAC 100 | 666 | 242 | 1384 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 2-1A | <0.05 |

| AWB- | L3 | SPC | DAC 100 | 280 | 381 | 994 | –0.10 | 0.06 | 11 | Fig. 2-1A | >0.05 |

| AWC- | L3 | SPC | DAC 100 | 248 | 477 | 1157 | –0.20 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 2-1A | >0.05 |

| ASE- | L3 | SPC | DAC 100 | 552 | 870 | 1797 | –0.18 | 0.06 | 11 | Fig. 2-1A | >0.05 |

| ASH- | L3 | SPC | DAC 100 | 286 | 166 | 655 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 10 | Fig. 2-1A | <0.05 |

| ASK- | L3 | SPC | DAC 100 | 321 | 272 | 856 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 10 | Fig. 2-1A | <0.05 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1758 | 163 | 2006 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 19 | Fig. 4B | — |

| AWB::TeTx line 12 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 872 | 84 | 1003 | 0.79 | 0.04 | 11 | Fig. 4B | 0.4683 |

| AWB::TeTx line 2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 234 | 23 | 260 | 0.81 | 0.02 | 3 | Table 1 | 0.9668 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 1738 | 573 | 2955 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 25 | Fig. 4B | — |

| AWB::TeTx line 12 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 634 | 214 | 949 | 0.44 | 0.07 | 10 | Fig. 4B | 0.8496 |

| AWB::TeTx line 2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 256 | 80 | 377 | 0.47 | 0.09 | 3 | Table 1 | 0.8941 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 855 | 79 | 990 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 4C | — |

| AWC::TeTx | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 672 | 86 | 815 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 11 | Fig. 4C | 0.2740 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 871 | 327 | 1385 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 4C | — |

| AWC::TeTx | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 516 | 205 | 816 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 12 | Fig. 4C | 0.8106 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 928 | 132 | 1128 | 0.71 | 0.03 | 11 | Fig. 4D | — |

| ASK::TeTx | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 667 | 106 | 820 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 11 | Fig. 4D | 0.7824 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 823 | 288 | 1229 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 11 | Fig. 4D | — |

| ASK::TeTx | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 375 | 169 | 609 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 11 | Fig. 4D | 0.2431 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1988 | 207 | 2289 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 18 | Fig. 4E | — |

| AWB,AWC,ASK::TeTx line 5 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 544 | 85 | 687 | 0.67 | 0.03 | 12 | Fig. 4E | 0.01149 |

| AWB,AWC,ASK::TeTx line 2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 662 | 147 | 898 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 11 | Table1 | 0.01 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 1044 | 261 | 1441 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 14 | Fig. 4E | — |

| AWB,AWC,ASK::TeTx line 5 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 576 | 248 | 939 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 13 | Fig. 4E | 2.87E–03 |

| AWB,AWC,ASK::TeTx line 2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 476 | 215 | 827 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 11 | Table1 | 6.34E–03 |

| N2 | Adult | Preference | DAC 0.1, PYR 0.8mg/ml | 1222 (DAC) | 761 (PYR) | 1983 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 14 | Fig. 4F* | — |

| AWB,AWC,ASK::TeTx line 5 | Adult | Preference | DAC 0.1, PYR 0.8mg/ml | 292 (DAC) | 440 (PYR) | 732 | –0.20 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 4F | 6.62E–09 |

| N2 | L3 | Preference | DAC 0.1, PYR 0.8mg/ml | 164 (DAC) | 681 (PYR) | 845 | –0.61 | 0.04 | 12 | Fig. 4F* | — |

| AWB,AWC,ASK::TeTx line 5 | L3 | Preference | DAC 0.1, PYR 0.8mg/ml | 47 (DAC) | 145 (PYR) | 192 | –0.52 | 0.06 | 10 | Fig. 4F | 0.1926 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 719 | 290 | 1336 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 13 | Fig. 4-1A | — |

| AWB::TeTx line 12 |

L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1087 | 349 | 1835 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 11 | Fig. 4-1A | 0.3929 |

| AWB::TeTx line 2 |

L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 675 | 240 | 1210 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 5 | Table 1 | 0.9479 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 1410 | 752 | 2812 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 22 | Fig.4-1A* | — |

| AWB::TeTx line 12 |

L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 470 | 231 | 956 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 11 | Fig. 4-1A | 0.8853 |

| AWB::TeTx line 2 |

L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 71 | 42 | 166 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 3 | Table 1 | 0.9606 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 602 | 260 | 1199 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 12 | Fig.4-1B* | — |

| AWC::TeTx | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 439 | 132 | 697 | 0.44 | 0.06 | 11 | Fig. 4-1B | 0.7025 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 503 | 427 | 1256 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 14 | Fig. 4-1B | — |

| AWC::TeTx | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 315 | 215 | 730 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 4-1B | 0.1650 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 617 | 256 | 1142 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 11 | Fig. 4-1C | — |

| ASK::TeTx | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 506 | 143 | 788 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 11 | Fig. 4-1C | 0.1666 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 435 | 357 | 1102 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 12 | Fig. 4-1C | — |

| ASK::TeTx | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 252 | 170 | 623 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 4-1C | 0.2759 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 900 | 251 | 1424 | 0.46 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 4-1D | — |

| AWB,AWC,ASK::TeTx line 5 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 375 | 89 | 622 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 10 | Fig. 4-1D | 0.6579 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 742 | 317 | 1373 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 10 | Fig. 4-1D | — |

| AWB,AWC,ASK::TeTx line 5 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 180 | 77 | 361 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 10 | Fig. 4-1D | 0.9266 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 737 | 112 | 900 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 5B | — |

| AWC::tom-1A | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 762 | 56 | 849 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 14 | Fig. 5B | 0.0221 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 624 | 231 | 1165 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 12 | Fig. 5B* | — |

| AWC::tom-1a | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 352 | 127 | 588 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 13 | Fig. 5B | 0.0192 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 1525 | 519 | 2291 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 17 | Fig. 5C | — |

| AWB::tom-1A line 18 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 598 | 133 | 841 | 0.55 | 0.03 | 10 | Fig. 5C | 0.0279 |

| AWB::tom-1A line 10 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 771 | 174 | 1050 | 0.57 | 0.05 | 10 | Table 1 | 0.0517 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 1410 | 752 | 2812 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 22 | Fig. 5C | — |

| AWB::tom-1a line 18 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 300 | 163 | 640 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 12 | Fig. 5C | 0.7991 |

| AWB::tom-1a line 10 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 141 | 64 | 280 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 6 | Table 1 | 0.6714 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 1875 | 633 | 2798 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 21 | Fig. 5D | — |

| ASK::tom-1A line 1 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 612 | 129 | 802 | 0.6 | 0.04 | 12 | Fig. 5D | 3.20E–03 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 1410 | 752 | 2812 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 22 | Fig. 5D | — |

| ASK:: tom-1a line 1 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 244 | 103 | 467 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 10 | Fig. 5D | 0.8374 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 813 | 264 | 1203 | 0.46 | 0.04 | 12 | Fig. 5-1A | — |

| AWC::tom-1A | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 679 | 148 | 886 | 0.60 | 0.05 | 15 | Fig. 5-1A | 0.1612 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 362 | 357 | 974 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 5-1A | — |

| AWC::tom-1a | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.01 | 276 | 151 | 610 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 11 | Fig. 5-1A | 8.97E–03 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1179 | 102 | 1338 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 14 | Fig. 5-1B | — |

| AWB::tom-1a line 18 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 544 | 20 | 575 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 5-1B | 0.0535 |

| AWB::tom-1a line 10 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 645 | 41 | 711 | 0.85 | 0.06 | 11 | Table 1 | 0.5762 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1738 | 573 | 2955 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 25 | Fig.5-1B* | — |

| AWB::tom-1a line 18 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 212 | 105 | 406 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 10 | Fig. 5-1B | 0.1370 |

| AWB::tom-1a line 10 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 165 | 54 | 312 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 8 | Table 1 | 0.9818 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1758 | 163 | 2006 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 19 | Fig. 5-1C | |

| ASK::tom-1A line 1 | Adult | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 621 | 52 | 684 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 12 | Fig. 5-1C | 0.9466 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 1738 | 573 | 2955 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 25 | Fig.5-1C* | — |

| ASK:: tom-1a line 1 | L3 | SPC | DAC 0.1 | 242 | 72 | 397 | 0.43 | 0.08 | 10 | Fig. 5-1C | 0.5807 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | BZ 0.1 | 1575 | 333 | 1947 | 0.64 | 0.04 | 17 | Fig. 5-1D | — |

| AWC::tom-1A | Adult | SPC | BZ 0.1 | 706 | 181 | 998 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 10 | Fig. 5-1D | 0.0244 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | BZ 0.1 | 1138 | 402 | 1843 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 15 | Fig. 5-1D | — |

| AWC::tom-1A | L3 | SPC | BZ 0.1 | 375 | 148 | 683 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 5-1D | 0.4917 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | IAA 0.1 | 1784 | 97 | 1940 | 0.87 | 0.03 | 17 | Fig. 5-1E | — |

| AWC::tom-1A | Adult | SPC | IAA 0.1 | 602 | 60 | 706 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 5-1E | 0.1000 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | IAA 0.1 | 1111 | 119 | 1381 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 10 | Fig. 5-1E | — |

| AWC::tom-1A | L3 | SPC | IAA 0.1 | 536 | 76 | 701 | 0.66 | 0.05 | 10 | Fig. 5-1E | 0.2885 |

| N2 | Adult | SPC | NON 10 |

858 | 1516 | 2790 | –0.24 | 0.06 | 23 | Fig. 5-1F | — |

| AWC::tom-1A | Adult | SPC | NON 10 |

207 | 364 | 712 | –0.22 | 0.06 | 8 | Fig. 5-1F | 0.9443 |

| N2 | L3 | SPC | NON 10 |

679 | 1601 | 2974 | –0.31 | 0.05 | 20 | Fig. 5-1F | — |

| AWC::tom-1A | L3 | SPC | NON 10 |

178 | 284 | 692 | –0.15 | 0.11 | 8 | Fig. 5-1F | 0.3410 |

Summary counts for all chemotaxis behavior in response to varying odor concentrations. Chemotaxis index (CI) = [(#A + #B) – (#F + #E)]/(#A + #B + #C + #F + #E + #D). Diacetyl preference index (PI) = (total odor responders) – (total control responders)/total responders. p-values are also reported here. DAC, diacetyl; BZ, benzaldehyde; IAA, isoamyl alcohol; NON, 2-nonanone; PYR, pyrazine; SPC, square plate chemotaxis. *Wild–type data used in generating multiple figures.

Tracking

To assess the speed of L3 and adults, we recorded their locomotion on modified chemotaxis assay plates using a Pixelink camera PL-741B and analyzed their movements using custom software (Calhoun et al., 2015). The modified chemotaxis assay is a variant of the odor preference assay described above (see also Fig. 1-1B). Briefly, animals were washed once in M9+MgSO4 followed by three times in S Basal. Ten to thirty animals were placed at the origin and allowed to move toward a diacetyl spot (1/1000) on a round 6-cm plate for 30 min. Data presented were collected from at least four plates over three different days.

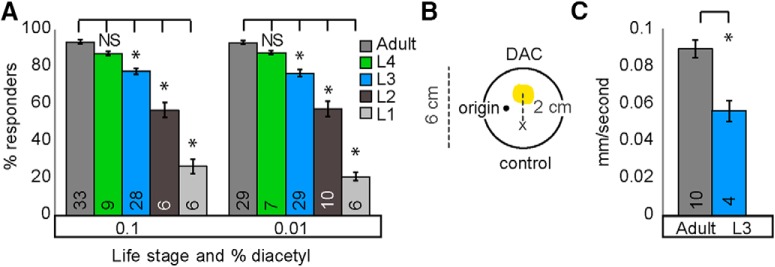

Figure 1-1.

A, Larval worms generally respond less than adults in attractive diacetyl chemotaxis assays. Less than 50% of L1 and L2 stage worms responded in diacetyl behavioral assays so subsequent experiments focused on L3 and later stages. Averages and s.e.m. are shown. Numbers in brackets in or above each bar indicate number of assay plates. Data was compared using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (*=p<0.05). B, Schematic of modified round plate assay used to track speed while 10-30 worms performed chemotaxis. (See also Materials and Methods). C, Adult populations move faster than L3 populations during attractive diacetyl chemotaxis. Averages and s.e.m. are shown. Numbers in each bar indicate number of assay plates. Data were compared using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests (*p < 0.05).

Calcium imaging

Transgenic animals expressing GCaMP family of calcium indicators under cell-selective promoters have been previously described (Leinwand et al., 2015). For this study, we recorded from sensory neurons expressing either GCaMP2.2b or GCaMP3. We developed a novel device to trap and record activity from neurons in L3 juveniles. Briefly (see also Fig. 3A), the L3 device contains channels of three thicknesses: the worm trap channel (10 μm thick), the stimulus-buffer flow channels (40 μm thick), and the inlet and outlets channel (65 μm thick; see also Multimedia File 1 to observe flow patterns and Multimedia File 2 for the AutoCAD design of the L3 device). Adult neurons were imaged as previously described (Chalasani et al., 2007; Chronis et al., 2007). Both adults and juveniles were exposed to identical diacetyl concentrations with stimulus added to the nose at t = 10 s and removed at t = 130 s in each recording. To determine odor responsiveness, we compared the averages and standard deviation of the ratio of ΔF/F0 for a given neuron stimulated with odor to buffer controls. In all imaging traces, the average fluorescence in a 3-s window for t = 3–6 s for on-responses (F0ON) and 121–124 s for off-responses (F0OFF) were used as baselines. Neurons whose ΔF/F0 value was >3 standard deviations above the buffer responses were counted as responders (see also Table 2).

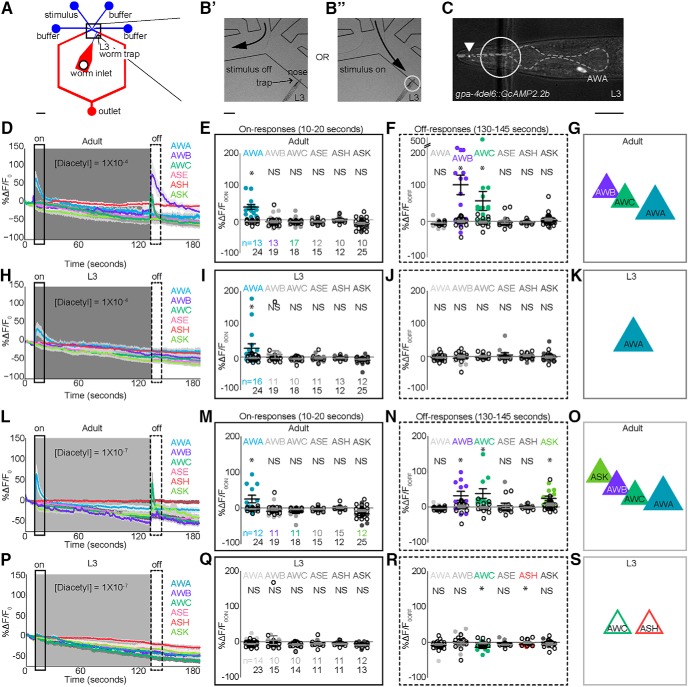

Figure 3.

Juveniles and adults use different sensory neurons to encode diacetyl. A, Schematic of novel PDMS-based microfluidic device for imaging L3 neurons (see also Materials and Methods). B, Magnified views of L3 worm (circled region) trapped in device with stimulus off (B′) or stimulus on (B″). C, Example L3 AWA expressing GCaMP2.2b under a reduced gpa-4 promoter. Anterior is to the left. White arrowhead indicates portion of dendritic tip in nose. Dashed gray outlines pharynx; used to landmark the position of sensory neuron cell bodies. D, L, Adult AWA, AWB, AWC, ASE, ASK, and ASH responses to different concentrations of diacetyl stimulus. Solid lines indicate average, and the light shadow represents SEM. Gray box here and in subsequent figures highlights stimulus duration (10–130 s). E, M, Scatterplots showing ratio of fluorescence changes (average) in a 10-s window (black rectangle) after stimulus addition (on-responses, 10–20 s). F, N, Average responses in a 15-s window (dashed rectangle) after stimulus removal (off-responses, 130–145 s). A similar analysis was performed on L3, and the resulting traces and scatter plots are shown in H–K and P–S. Responders were estimated by comparing the average responses of individual neurons to the baseline controls (see Table 2 and Materials and Methods for details). Numbers of neurons imaged in each condition are shown in E, I, M, and Q (n). Adult AWA neurons responded to the addition of all presented [diacetyl], whereas L3 AWA neurons responded only to the highest presented [diacetyl] (compare D, H, L, and P). Moreover, adult AWB, AWC, and ASK responded to the removal of odor. Data in E, F, I, J, M, N, Q, and R were compared using two-tailed, unpaired t-tests (*p < 0.05). Solid colored circles represent responses of a given cell to odor, and open black circles represent the same cell’s response to a buffer-only control. Scale bar is 300 μm in A, 40 μm in B′, and 10 μm in C. G, K, O, S, Schematics of adult and L3 neurons encoding diacetyl.

Table 2.

Sensory neurons that responded to the addition or removal of diacetyl

| [DAC] | SN | Stage | +1 SD ON responder | +2 SD ON responder | +3 SD ON responder | +1 SD OFF responder | +2 SD OFF responder | +3 SD OFF responder | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 × 10−7 | AWA | Adult | 8 | 6 | 6 | # | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.50 | % | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.08 | |||

| 1 × 10−7 | AWA | L3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | AWB | Adult | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | AWB | L3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | AWC | Adult | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 3 | |

| 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.27 | 0.27 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | AWC | L3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | ASE | Adult | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | ASE | L3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.09 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | ASH | Adult | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | ASH | L3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | ASK | Adult | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 1 | |

| 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.08 | ||||

| 1 × 10−7 | ASK | L3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | AWA | Adult | 13 | 13 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | AWA | L3 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | AWB | Adult | 2 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 8 | |

| 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.62 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | AWB | L3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | AWC | Adult | 9 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 9 | 8 | |

| 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.47 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | AWC | L3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | ASE | Adult | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | ASE | L3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.18 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | ASH | Adult | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | ASH | L3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | ASK | Adult | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1 × 10−4 | ASK | L3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

Table 3.

Summary of all strains and genotypes

| Strain | Genotype | Description | Figures |

|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | Wild type | Figs. 1B–H,J; 1–1; 2A,C,E; 2–1B; 4B–F; 4–1; 5B–D; 5–1; Table 1 | |

| CX4 | odr-7 (ky4) X | “AWA-” | Figs. 2A,C,E; 2–1B; Table 1 |

| JN1715 | peIs1715 [str-1p::mCasp-1, unc-122p::venus] | “AWB-” | Figs. 2A,C,E; 2–1B; Table 1 |

| PY7502 | oyIs85 [ceh36delp::TU#813; ceh-36delp::TU#814; srtx-1p::GFP, unc-122p::dsRED] | “AWC-” | Figs. 2A,C,E; 2–1B; Table 1 |

| PR672 | che-1(p672) I | “ASE-” | Figs. 2A,C,E; 2–1B; Table 1 |

| JN1713 | peIs1713 [sra-6p::mCasp-1, unc-122p::mcherry] | “ASH-” | Figs. 2A,C,E; 2–1B; Table 1 |

| QS4 (PS6025) |

qrIs2 [sra-9p::mCasp-1, elt-2p::GFP] | “ASK-” | Figs. 2A,C,E; 2–1B; Table 1 |

| PY6554 | oyEx6554 [gpa-4p::GCaMP2.2b, unc-122p::dsRed] | “AWA” | Figs. 3C–O, 3–1A–D; Table 2 |

| PY7336 | oyEx7336 [str-1p::GCaMP3, unc-122p::dsRed] | “AWB” | Figs. 3C–O; Table 2 |

| CX10536 | kyEx2595 [str-2p::GCaMP2.2b;unc-122p::GFP] | “AWC” | Figs. 3C–O; Table 2 |

| IV388 | ueEx7 [gcy-7p::GCaMP3, unc-122p::GFP] | “ASE” | Figs. 3C–O; Table 2 |

| IV346 | kyEx2865 [sra-6p:: GCaMP3, unc-122p::GFP] | “ASH” | Figs. 3C–O; 3–1E; Table 2 |

| CX10981 | kyEx2866 [sra-9p::GCaMP2.2b; unc-122p::GFP] | “ASK” | Figs. 3C–O; Table 2 |

| IV746 | ueEx535 [str-1p::TeTx:sl2mcherry, elt-2p::GFP] |

“AWB::TeTx (line 2)” |

Table 1 |

| IV747 | ueEx536 [str-1p::TeTx:sl2mcherry, elt-2p::GFP] |

“AWB::TeTx (line 12)” |

Figs. 4B; 4–1A; Table 1 |

| IV216 | ueEx131 [odr3p:TeTx:sl2mcherry, elt-2p::GFP] | “AWC::TeTx” | Figs. 4C; 4–1B; Table 1 |

| CX11576 | kyEx3097 [sra-9p::tetx::sl2mcherry, elt-2p::GFP] | “ASK::TeTx” | Figs. 4D; 4–1C; Table 1 |

| IV683 | ueEx473 [str-1p::TeTx:sl2mcherry, odr-3p::TeTx:sl2mcherry, sra-9p::TeTx:sl2mcherry, elt-2p::GFP] |

“AWB,AWC, ASK::TeTx (line 2)” |

Table 1 |

| IV684 | ueEx474 [str-1p::TeTx:sl2mcherry, odr-3p::TeTx:sl2mcherry, sra-9p::TeTx:sl2mcherry, elt-2p::GFP] |

“AWB,AWC, ASK::TeTx (line 5)” |

Figs. 4E; 4–1D; Table 1 |

| PY10824 (IV387) | pyEx10824 [ceh-36delp::tom-1A::sl2mcherry sense + anti-sense, unc-122p::GFP] | “AWC::tom-1A” | Figs. 5B, 5–1A,D–F; Table 1 |

| IV745 | ueEx531 [str-1p::tom-1:: sl2mcherry sense+anti-sense, elt-2p::GFP] | “AWB::tom-1A (line 10)” | Table 1 |

| IV742 | ueEx531 [str-1p::tom-1:: sl2mcherry sense+anti-sense, elt-2p::GFP] | “AWB::tom-1A (line 18)” | Figs. 5C; 5–1B; Table 1 |

| IV750 | ueEx539 [sra-9::tom-1A::sl2mcherry sense+anti-sense, elt-2p::GFP] | “ASK::tom-1A (line 1)” | Figs. 5D; 5–1C; Table 1 |

Movie showing the switching of the flow patterns between “stimulus on” and “stimulus off” in the novel L3-microfluidic device. A stimulus change occurs at 2 s in clip. Movie is sped up 30×.

Strains and molecular biology

Strains were cultured using standard practices (Brenner, 1974). A 4.5-kb sequence fragment for str-1 promoter (AWB; Harris et al., 2014) was synthesized (Genscript) and used to express tetanus toxin and tom-1A sense and antisense constructs to block and increase neurotransmission, respectively (Schiavo et al., 1992; Gracheva et al., 2007). To misexpress tetanus toxin in AWB, AWC, and ASK simultaneously, we performed germline transformations by microinjection of plasmids (Mello and Fire, 1995) at 100 ng/μl each of str-1p::TeTx:sl2mcherry, odr-3p:TeTx:sl2mcherry (Calhoun et al., 2015), and sra-9p::TeTx:sl2mcherry (Calhoun et al., 2015) along with 10 ng/μl elt-2p::gfp as a co-injection marker. Similarly, to misexpress tetanus toxin in AWB, we injected str-1p::TeTx:sl2mcherry plasmid at 100 ng/μl and elt-2p::GFP plasmid at 10 ng/μl. We also generated lines specifically expressing tom-1A sense and antisense in AWB by injecting str-1p::tom-1A sense and anti-sense plasmid at 50 ng/μl and elt-2p::GFP plasmid at 10 ng/μl and in ASK by injecting sra-9p::tom-1A sense and anti-sense plasmid at 100 ng/μl and elt-2p::GFP plasmid at 10 ng/μl.

Results

Juveniles perform worse than adults at attractive chemotaxis behaviors

To test whether juveniles and adults perform similarly on odor-evoked food-seeking tasks, we used a chemotaxis assay in which animals can move toward or away from a volatile test compound (Fig. 1A). Worms were washed from growth plates and placed in a central region of the assay plates (termed “origin”; see also Materials and Methods). We found that >70% of animals in the third larval stage, L3, left the origin, allowing them to respond to the odor gradients. In contrast, <50% of the younger L2 and L1 larvae left the origin, suggesting that the chemotaxis assay is unsuitable to analyze the behavior of very young worms (Fig. 1-1A). Thus, we focused our analysis on L3 juveniles, comparing L3 and adult behavior in response to a number of volatile food-associated odors. We found that L3 juveniles were significantly less attracted than adults to diacetyl (Fig. 1B), isoamyl alcohol (Fig. 1C), benzaldehyde (Fig. 1D), and 2,3-pentanedione (Fig. 1E). We also found that L3 juveniles and adults have different locomotion speeds (Fig. 1-1B, C). To eliminate the possibility that defective L3 behavior is simply a result of slower movement speed, we tested their performance to additional odors. Both L3 and adults similarly avoided the volatile repellent 2-nonanone (Fig. 1F), suggesting that L3 juveniles are indeed competent to generate adult-like chemotaxis responses. We found additional evidence of similarity between L3 juveniles and adults in their responses to repellents. Both L3 juveniles and adults avoided high concentrations of the volatile odor, benzaldehyde (Fig. 1G; Yoshida et al., 2012). However, we observed that L3 juveniles are less repelled than adults from high concentrations of diacetyl (Fig. 1H), suggesting that diacetyl circuits are specifically altered during the juvenile-to-adult transition.

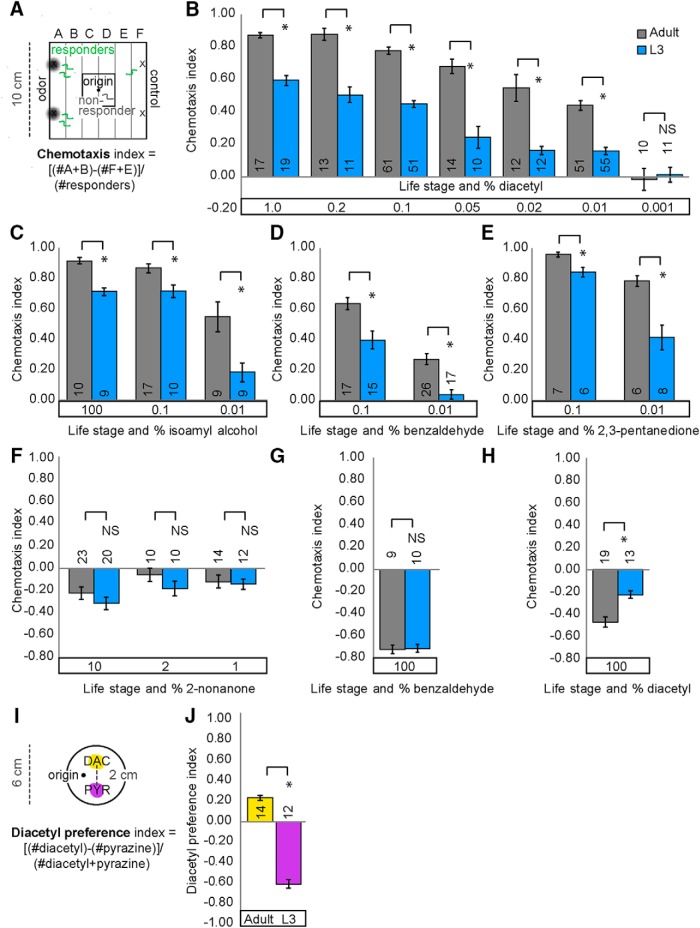

Figure 1.

Juveniles and adults differ in attractive chemotaxis behavior. A, Schematic of square plate (10 cm) assay used to assess chemotaxis behavior; both adult and L3 assays were conducted for 1 h (see also Materials and Methods). B, Wild-type (N2) adult (gray) and L3 (blue) differ in their attraction across a range of attractive diacetyl concentrations. Wild-type adult and L3 also differ in chemotaxis behavior for various attractive AWC-sensed odors: isoamyl alcohol (C), benzaldehyde (D), and 2,3-pentandione (E). (F) Adults and juveniles are similarly repulsed by AWB-sensed 2-nonanone. Their behavior does not differ for repulsion to 100% benzaldehyde (G) but does for repulsive concentrations of diacetyl (H). I, Schematic of round plate (6 cm) assay used to assess stage-specific choice preference (Fujiwara et al., 2016). J, N2 adult prefer diacetyl (DAC) whereas N2 L3 prefer pyrazine (PYR). Averages and SEM are shown with numbers on each bar representing the number of assays. Brackets above bars indicate data compared using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests (*p < 0.05).

To provide further evidence that L3 juveniles and adults respond differently to diacetyl, we conducted an odor preference assay in which animals were presented with opposing gradients of diacetyl and pyrazine (Fig. 1I; Fujiwara et al., 2016). We found that L3 juveniles prefer pyrazine, whereas adults prefer diacetyl (Fig. 1J), consistent with recently published results (Fujiwara et al., 2016). The chemotaxis results reveal that L3 juveniles have impaired responses to attractive and repulsive gradients of diacetyl and attractive gradients of isoamyl alcohol, benzaldehyde, and 2,3-pentanedione. Because AWA sensory neurons are required for diacetyl attraction and AWC neurons drive attraction toward isoamyl alcohol, benzaldehyde, and 2,3-pentandione (Bargmann et al., 1993; Bargmann, 2006), our results suggest that behaviors toward AWA- and AWC-sensed odors are altered during development. These results are consistent with a recent study showing that L3 juveniles, compared with adults, have reduced diacetyl attraction and altered odor preferences (Fujiwara et al., 2016). Moreover, these results show that C. elegans executes age-specific food and diacetyl-seeking behavior.

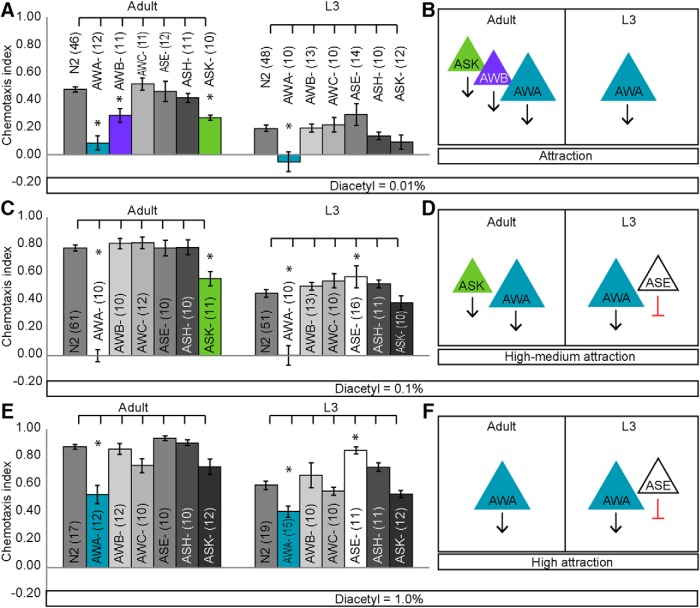

Adults and juveniles require multiple sensory neurons to drive diacetyl chemotaxis

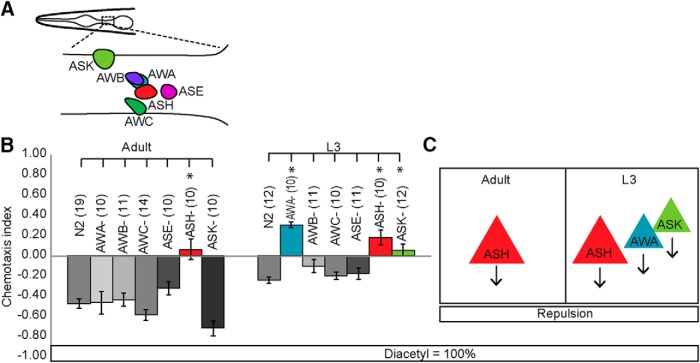

Because L3 juveniles have altered responses to both attractant and repellent concentrations of diacetyl, we focused our analysis on the mechanisms generating developmental plasticity to the AWA-sensed diacetyl. However, L3 juveniles, similar to adults, have all 12 pairs of amphid chemosensory neurons (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977; White et al., 1986). Thus, we tested the hypothesis that adults and juveniles differ in chemotaxis because they use, rather than possess, different sets of neurons to drive behavior. To probe the underlying sensory circuit generating attraction to diacetyl in adults and juveniles, we tested the behavioral responses of animals lacking individual chemosensory neurons including those that sense volatile odors: AWA, AWB, AWC, ASH (Larsch et al., 2013; Taniguchi et al., 2014; Zaslaver et al., 2015), water soluble chemicals: ASE (Suzuki et al., 2008), food: ASK (Calhoun et al., 2015), and temperature: AFD (Satterlee et al., 2001). We analyzed animals expressing caspase under ASH (sra-6), ASK (sra-9), AWC (ceh-36), and AWB (str-1) selective promoters (Beverly et al., 2011; Taniguchi et al., 2014) or mutants in transcription factors that specifically eliminate functional ASE (che-1), AFD (ttx-1), and AWA (odr-7) neurons (Fig. 2-1A; Sengupta et al., 1994; Satterlee et al., 2001; Uchida et al., 2003). Consistent with previous results (Bargmann et al., 1993), we found that adults missing AWA neurons were defective in their diacetyl attraction (Fig. 2A). Additionally, we found that adult animals lacking AWB and ASK neurons had reduced attraction to diacetyl (Fig. 2A). In contrast, we found that L3 animals lacking AWA, but not other chemosensory neurons, had severely impaired diacetyl attraction (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that whereas AWA drives attraction to diacetyl in both juveniles and adults, AWB and ASK are additionally required in adults (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2-1.

Juveniles and adults also have different sensory neurons for repulsive diacetyl behavior. A, Schematic of sensory neurons tested in chemotaxis behavior. B, Behavioral responses of adults and L3 to a repulsive concentration of diacetyl. C, Schematic summarizing adult and L3 repulsive sensory neurons. Averages and SEM are shown. Numbers in brackets in or above each bar indicate number of assay plates. Data were compared using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (*p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Juveniles and adults require different sets of sensory neurons for attractive diacetyl chemotaxis. A–E, AWA is required in adults and juveniles for attraction to diacetyl. A, B, Interestingly, AWB and ASK are also required in adults, but not L3, for attraction. C, D, At intermediate levels of diacetyl, AWA and ASK are required in adults for attraction. ASE is also involved in L3 attraction. E, F, At a high level of diacetyl, only AWA is required in adults. By contrast, AWA and ASE play roles in L3 chemotaxis. Averages and SEM are shown in A, C, and E with numbers on each bar representing the number of assays. Data were compared using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (*p < 0.05). B, D, F, Schematics of adult and L3 neurons required for attractive diacetyl behavior.

Odor sensory codes are modified by stimulus strength (Yoshida et al., 2012; Leinwand et al., 2015), so we tested whether the diacetyl sensory code is similarly altered by analyzing behavioral responses to other diacetyl concentrations. In each of the concentrations tested, we found that different combinations of sensory neurons are required in adults and juveniles. We found that at intermediate attractive concentrations, adults require AWA and ASK neurons, whereas juveniles use AWA and ASE sensory neurons for attractive chemotaxis (Fig. 2C, D). In contrast, at highly attractive concentrations, juveniles use ASE and AWA, whereas adults require only AWA to drive attraction (Fig. 2E, F). Next, we tested whether juveniles and adults use different sensory neurons to generate repulsion. We found that adults use ASH neurons, whereas juveniles use ASH, AWA, and ASK neurons to avoid undiluted diacetyl (Fig. 2-1). Together, these results indicate that adults and juveniles require different combinations of sensory neurons to drive behavioral responses to food-associated diacetyl odor.

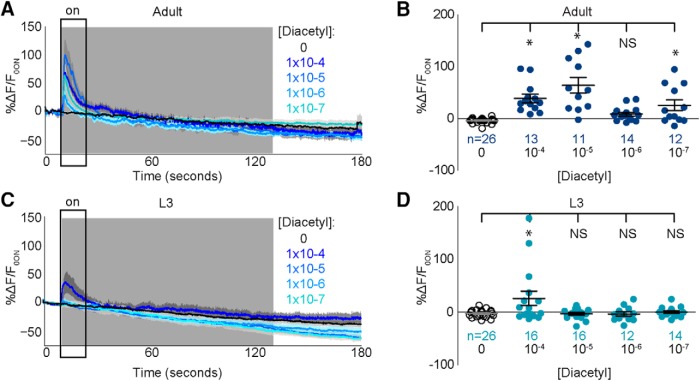

Juveniles and adults use different sets of sensory neurons to encode diacetyl

To test odor-evoked neuronal responses underlying odor behavior in juveniles, we developed a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based microfluidic device (Fig. 3A) for calcium imaging that successfully trapped L3 juveniles (Fig. 3B, C). We used a similar device to record adult sensory neuron responses to diacetyl (Fig. 3-1A, B; Chalasani et al., 2007; Leinwand et al., 2015) and validated our novel imaging device by recording activity from AWA neurons in L3 juveniles (Fig. 3-1C, D). Consistent with experiments using adults (Larsch et al., 2015), we found that juvenile AWA neurons also responded to addition of diacetyl odor (Fig. 3-1A–D) confirming the utility of the L3 trap to record juvenile neuronal responses.

Figure 3-1.

AWA encodes the addition of diacetyl in juveniles and adults. A, Adult AWA responses to different diacetyl concentrations. Solid lines indicate average, and the light shadow represents SEM. Gray box here and in subsequent figures highlights stimulus duration (10–130 s). B, Scatterplots showing average responses in a 10-s window immediately after stimulus addition (black rectangle). C, D, A similar analysis was performed on L3, and the resulting traces (C) and scatterplots (D) are shown. Solid colored circles represent responses of a given cell to odor, and open black circles represent the same cell’s response to a buffer-only control. Responders were estimated by comparing the average responses of individual neurons to the baseline controls (see Fig. 3-2 and Materials and Methods for details). Numbers of neurons imaged in each condition are shown in B and D (n). Adult AWA neurons responded to all presented [diacetyl], whereas L3 AWA neurons responded only to the highest presented [diacetyl] (compare B and D). E, Representative trace of L3 ASH responding to the addition of a repellent (black arrow indicates start of 2-nonanone stimulation). Data in B and D were compared using two-tailed, unpaired t-tests (*p < 0.05).

To confirm a functional role for the sensory neurons identified above through behavioral analysis, we examined their activity in L3 and adults. We hypothesized that diacetyl is encoded across multiple neurons, as previous studies have shown that chemical stimuli are encoded by the combined activity of multiple sensory neurons (Harris et al., 2014; Leinwand et al., 2015; Zaslaver et al., 2015). We examined the activity of several amphid sensory neurons, including those that sense volatile odors: AWA, AWB, AWC, ASH (Larsch et al., 2013; Taniguchi et al., 2014; Zaslaver et al., 2015); water-soluble chemicals: ASE (Suzuki et al., 2008); and food: ASK (Calhoun et al., 2015). Consistent with our behavioral analysis, we found that in both adults (Fig. 3D–G) and juveniles (Fig. 3H–K), AWA neurons respond to addition of diacetyl. Next, we analyzed the averaged responses of additional amphid sensory neurons. In both adults and L3, we found that, except for AWA, none of the neurons analyzed responded to the addition of diacetyl stimulus (Fig. 3D, E, H, and I). Rather, we observed that adult AWC and AWB neurons responded to the removal of stimulus (Fig. 3F), whereas we observed no such activation of these neurons in L3 juveniles (Fig. 3J). Although AWC was previously implicated in driving attraction to diacetyl (Chou et al., 2001), our results reveal novel roles for AWB and ASK in encoding diacetyl. Moreover, we found that adult AWA responded to the addition of a lower diacetyl concentration, whereas AWB, AWC, and ASK neurons were activated by its removal (Fig. 3L–O), suggesting that diacetyl strength is likely encoded by activity in different combination of sensory neurons. On average, L3 sensory neurons did not respond to a lower diacetyl concentration, but AWC and ASH were weakly suppressed (Fig. 3P–S). Collectively, the imaging results show that L3 and adults use different sets of chemosensory neurons to encode diacetyl. Adult AWA neurons encode the addition of diacetyl, and activity in AWB, AWC, and ASK encodes its removal, whereas L3 animals use AWA activity to encode diacetyl at a higher concentration (Fig. 3G, K, O and S). These results are consistent with recent studies confirming a role for AWC (Larsch et al., 2015; Fujiwara et al., 2016) along with AWA in driving diacetyl attraction.

We observed discrepancies in the sensory circuits identified using behavior or neural activity as readouts for neuronal function. Our behavior analysis showed that adults use ASK and AWB neurons in addition to AWA to drive attraction, whereas our imaging analysis also identified a role for AWC in encoding diacetyl in the adult. Consistent with previous observations in the benzaldehyde circuit (Leinwand et al., 2015), we found that different combinations of sensory neurons encode the concentration of diacetyl stimulus. We suggest that these discrepancies may arise from variations in the stimuli that the animals experience in the two assays: animals respond to a gradient of diacetyl stimulus (with the concentration of the point source indicated) in behavior assays, and imaging studies record neuronal responses to a known concentration of odor delivered to the nose of the animal.

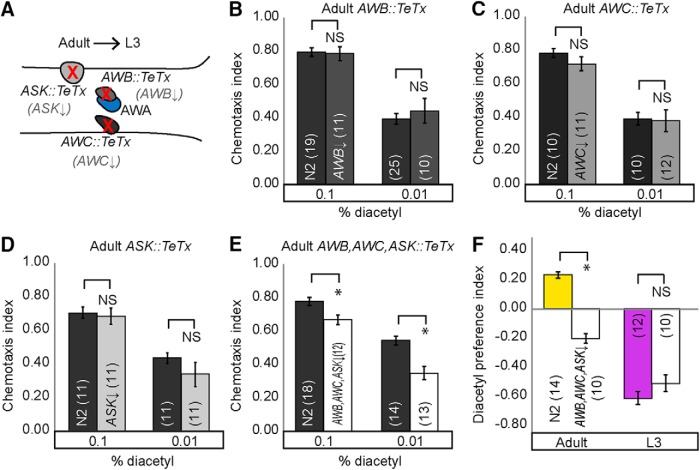

Altering the adult sensory code transforms adult behavior to juvenile-like states

We hypothesized that altering the adult sensory code, identified in behavioral and imaging experiments, by reducing neurotransmission from the additional sensory neurons that function specifically in adults for diacetyl-evoked behavior (Fig. 4A) would transform adult behavior into a L3-like state. We selectively blocked neurotransmission individually in AWB (Figs. 4B and 4-1A), AWC (Fig. 4C and 4-1B), and ASK (Figs. 4D and 4–1C) and in all three (Figs. 4E and 4-1D) by expressing tetanus toxin (TeTx). Previously, TeTx has been shown to block synaptic neurotransmission by cleaving synaptobrevin (Schiavo et al., 1992). In support of our hypothesis, TeTx misexpression in AWC, AWB, and ASK neurons together attenuates adult but not L3 diacetyl attraction (Figs. 4E and 4-1D). These results confirm our model that AWC, AWB, and ASK do not participate in driving diacetyl attraction in L3 juveniles. Moreover, blocking neurotransmission from AWC, AWB, and ASK individually did not affect adult (Fig. 4B–D) or L3 behavior (Fig. 4-1A–C), suggesting that these sensory neurons might be redundant in their ability to contribute to adult attraction to diacetyl. Additionally, we tested whether AWB, AWC, and ASK are required to generate age-appropriate odor preferences. We found that blocking neurotransmission from AWC, AWB, and ASK transformed adult preferences from diacetyl to pyrazine, without altering L3 odor preferences (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that neurotransmitter release from additional sensory neurons plays a crucial role in generating adult-specific responses: enhanced attraction to, and a preference for, diacetyl.

Figure 4.

Knocking down neurotransmission of cells specific to adult circuit results in juvenile-like behavior. A, Schematic for transforming adult to L3 behavior by misexpressing TeTx in AWB, AWC, and ASK neurons, and consequently decreasing synaptic transmission from those cells. Chemotaxis is not altered when TeTx is misexpressed individually in AWB*, AWC, or ASK (B–D), but does decline when misexpressed collectively in AWB, AWC, or ASK* (E). F, Adults have a juvenile-like odor preference. Adult worms with decreased synaptic transmission in AWB, AWC, and ASK neurons prefer pyrazine, unlike their wild-type counterparts. Averages and SEM are shown with numbers on each bar representing the number of assays. Data were compared using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests (*p < 0.05) and, when appropriate, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (B, E). *See also Table 1 for additional tested lines.

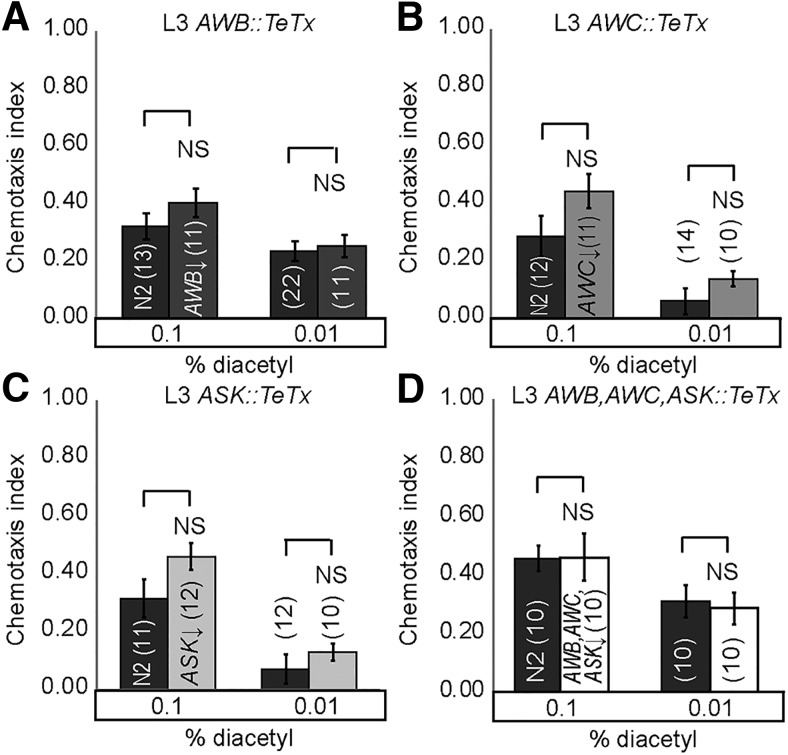

Figure 4-1.

Manipulating AWB, AWC, and ASK sensory neuron activity in L3. Decreasing synaptic transmission by TeTx misexpression in L3 AWC (A), AWB* (B), ASK (C), or all three (D) does not alter chemotaxis. Averages and SEM are shown. Numbers in brackets in or above each bar indicate number of assay plates. Data were compared using two-tailed, unpaired t-tests (B) with Bonferroni correction, *p < 0.05. See also Table 1 for additionally tested lines.

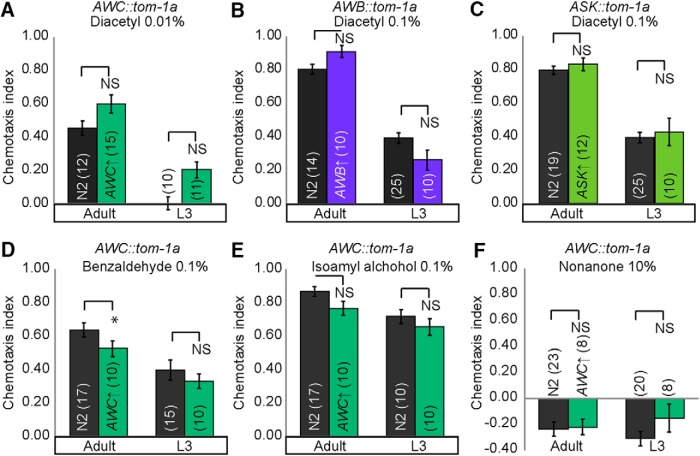

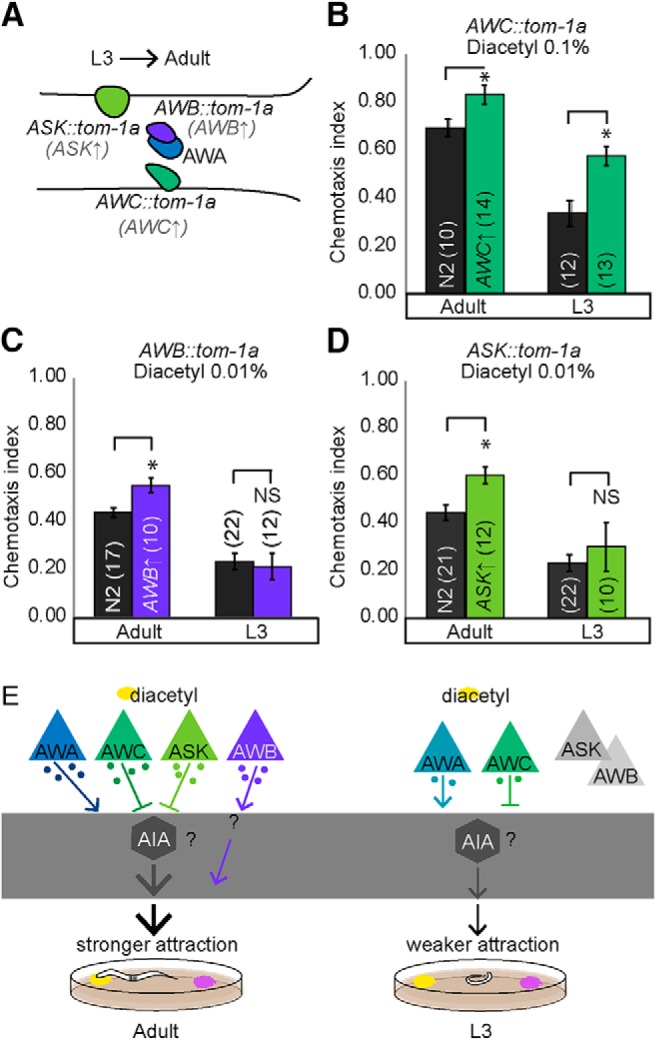

To further manipulate the adult and juvenile sensory codes, we artificially increased neurotransmission from target sensory neurons. Knocking down tomosyn (tom-1A in C. elegans) increases both classic neurotransmission and neuropeptide signaling by upregulating dense-core vesicle release (Gracheva et al., 2007; Leinwand et al., 2015) and synaptic vesicles (Hu et al., 2013). We predicted that increasing neurotransmission from juvenile or adult sensory neurons detecting diacetyl would improve diacetyl attraction (Fig. 5A). Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that increasing neurotransmission from AWC improves diacetyl attraction in both juveniles and adults (Fig. 5B), confirming a role for this neuron at both life stages. This result is inconsistent with our calcium imaging experiments, in which we did not observe juvenile AWC neuronal activity in response to diacetyl. However, we suggest that calcium imaging might not reveal all AWC neural activity, as has been previously reported for other amphid sensory neurons (Zahratka et al., 2015). In contrast, we found that increasing neurotransmission from AWB and ASK improved diacetyl attraction in adults, but not juveniles (Figs. 5C, D, and 5-1). These data are consistent with our behavioral and imaging analysis and suggest that AWB and ASK are exclusively used in adults for diacetyl attraction.

Figure 5.

Increasing neurotransmission from cells specific to the adult circuit enhances diacetyl attraction in a contextually appropriate manner. A, Schematic transforming L3 to adult behavior by knocking down tom-1A in AWC (B), AWB (C), and ASK (D). These manipulations specifically increase synaptic transmission from sensory neurons. B–D, Enhanced attraction in adults is observed only for concentration-appropriate sensory circuits (see also Figs. 2 and 5-1A–C). Chemotaxis improves in L3 worms lacking tom-1A in AWC (B) but not for AWB and ASK tom-1A knockdowns (C, D). Averages and SEM are shown in B–D with numbers on each bar representing the number of assays. Data were compared using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests (*p < 0.05). E, Developmental differences in neurotransmission may underlie plasticity of diacetyl attraction.

Figure 5-1.

Increasing neurotransmission from AWB, AWC, and ASK sensory neurons in adults and L3. Increasing synaptic transmission by knocking down tom-1a in AWC (A), AWB (B), and ASK (C) does not enhance behavioral performance of adults and juveniles to low or higher concentrations of diacetyl. Tom-1A knockdown also does not enhance behavioral performance of adults and juveniles to benzaldehyde (D), isoamyl alcohol (E), or 2-nonanone (F). Averages and SEM are shown. Numbers in brackets in or above each bar indicate number of assay plates. Data were compared using two-tailed, unpaired t-tests, *p < 0.05.

Discussion

Recent work showed that the diacetyl sensory circuit is modified by the developing germline leading to more robust attraction in the adult (Fujiwara et al., 2016). However, our results suggest a second nonexclusive mechanism that also explains developmental plasticity for diacetyl-evoked behavior.

In this study, we identify a novel role for altered sensory coding in driving the maturation of chemosensory circuits during development. Our imaging experiments reveal that adult AWA sensory neurons respond to the addition of diacetyl, whereas AWC, AWB, and ASK neurons respond to the removal of stimulus in a concentration-dependent manner. This combinatorial odor code has also been previously observed where multiple sensory neurons encode benzaldehyde (Leinwand et al., 2015) and isoamyl alcohol (Yoshida et al., 2012). Although AWC neurons have been implicated in diacetyl attraction (Chou et al., 2001), our results reveal a novel role for AWB and ASK in diacetyl attraction. We speculate that in adults AWB, AWC, and ASK neurons may initially be hyperpolarized by the addition of diacetyl and are activated upon its removal (Fig. 3D). Previous studies have identified a key role for AWA sensory neurons and the downstream AIA interneurons in sensing a broad range of diacetyl concentrations (Larsch et al., 2015). Additionally, this study also found that AWC sensory neurons acted upstream of these AIA interneurons in generating diacetyl attraction (Larsch et al., 2015). Previously, AWC neurons have also been shown to suppress AIA interneurons (Chalasani et al., 2010). Similarly, ASK might also inhibit AIA activity, as ablating ASK and AIA neurons has opposing effects on behavior (Gray et al., 2005). Because both AWC and ASK sensory neurons synapse onto AIA interneurons (White et al., 1986), we further hypothesize that these sensory neurons are likely to suppress AIA activity upon removal of diacetyl stimulus. Suppressing AIA interneurons increases turn behavior (Chalasani et al., 2007), perhaps enabling the animal to move toward the attractant. In addition, AWB neurons can function downstream of AWA neurons in refining attraction to benzaldehyde (Leinwand et al., 2015). Thus, we suggest that AWA neurons might also signal to AWB neurons to modify diacetyl attraction. Collectively, the combined activity across AWA, AWB, AWC, and ASK neurons enables adults to maintain strong diacetyl attraction, perhaps by modifying turn behaviors (Fig. 5E).

Through behavioral analyses of genetic mutants and transgenic animals, we show that both L3 and adults use AWA and AWC neurons to encode diacetyl, but that adults additionally use AWB and ASK neurons to encode the odor. By altering neurotransmission, we show that these additional sensory neurons play a crucial role in driving the enhanced adult attraction to diacetyl. Previous work has shown that neurotransmitter signaling can be altered by sensory context or aging (Leinwand and Chalasani, 2013; Leinwand et al., 2015). As development progresses, sensory experience, internal signals, and unfurling genetic programs modify the underlying neural pathways, perhaps at the level of neurotransmitter signaling, leading to a more complex and diverse adult-specific diacetyl sensory circuit that includes additional sensory neurons. We suggest that the larger adult circuit plays a crucial role in generating stronger attraction in the adults, perhaps by encoding more stimulus features or enabling a larger dynamic range for detection. Our results are consistent with those observed in desert locusts, in which adults show an increased number of chemical stimuli–responding sensory neurons compared with juveniles (Anton et al., 2002). We speculate that developmental plasticity allows juveniles to adapt to changes in their local environment, generating adults that can appropriately use available resources and even compensate for early negative experiences. This speculation is consistent with the observation that adult zebra finch males that experience starvation during development adapt compensatory mechanisms to enhance their reproductive fitness (Krause and Naguib, 2015).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: We thank C. Bargmann, Y. Iino, P. Sengupta, A. Frand, G. Jansen, K. Shen, T. Wakabayashi, Y. Zhang, C. Hammel, S. Lockery, Y. Lin, D. Portman, and Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) for strains and plasmids. We greatly appreciate Mark Saddler, Kyle De Alva, Daphne Bazopoulou, Jeffrey Kuhn, Sarah Leinwand, Caz O’Connor, Chris Benner, Max Shokirev, Lourdes Tames, and Zheng Liu for their technical help. We are also grateful to K.-F. Lee, K. Quach, L. Shipp, E. Lau, A. Pribadi, members of the Chalasani Lab, and J. Driscoll for critical comments, insights, and advice.

Synthesis

Reviewing Editor: Piali Sengupta, Brandeis University

Decisions are customarily a result of the Reviewing Editor and the peer reviewers coming together and discussing their recommendations until a consensus is reached. When revisions are invited, a fact-based synthesis statement explaining their decision and outlining what is needed to prepare a revision will be listed below. The following reviewer(s) agreed to reveal their identity: Koutarou Kimura.

Writing edits:

1. Introduction: The Introduction needs to be expanded to place the work in a broader context and to appeal to a broader readership. As it is currently written, it is far too narrowly focused even for the C. elegans community.

2. Methods: Please provide additional details in the Methods regarding the 'hatch-off' protocol, the new microfluidics device, and the chemotaxis assay (please see note about chemotaxis assay below). Also, please provide relevant details regarding the parameters for the calcium imaging experiments (or include reference to previous work if parameters are the same), including the version of GCaMP used in each experiment.

3. Chemotaxis assay: Please specifically note duration time and scale for the assay in the figure or figure legend. It seems like the L3s are not as efficient at chemotaxing to nearly all odorants, and since this effect generalizes across attractants, it is possible that their small size and reduced crawling speed makes them less efficient at positive chemotaxis. The authors don't seem to have clearly distinguished size effects from age effects with their assay. Based on the Fujiwara paper, larvae do in fact have different odor preferences- Fujiwara et al. controlled for possible size effects by doing an odor preference assay and still saw differences in adults vs. larvae - but no similar control is provided here. Thus, while Fujiwara et al. demonstrate changes in odor preferences, it's less clear what the authors are looking at here. This point would be particularly interesting to address with regard to Figure 4, where inactivation of AWB, ASK, and AWC in adults reduces attraction. If an odor preference assay had been used for this experiment, and the AWB-, ASK-, AWC- adults showed reversed odor preferences that were analogous to the odor preferences of L3s, this would be more convincing. With only a regular chemotaxis assay, it's hard to know whether the reduced behavioral response is really analogous to an L3-like state.

4. The statement "transforms adults into a juvenile-like state" is a bit strong - please reword throughout.

5. Use of the term 'sensory circuit': Since you haven't shown that the sensory neurons you identified are technically in a circuit (for eg. not clear whether each neuron is a primary sensor or drives responses in a second neuron), please reword.

6. There are references missing throughout - TeTx, tom-1, the Chronis reference for the microfluidics device. Wrong reference in line 182 - Should be Chou, Bargmann and Sengupta 2001. Since the Fujiwara manuscript is now published, this work needs to be discussed and referenced.

7. Please check grammar and syntax. Reviewers noted multiple errors that I am not listing here. Please remove the last paragraph in the Discussion which is redundant.

8. Figure 3-2 is not included in the manuscript.

Statistics:

Please ensure that you have used the appropriate statistical test. In several cases shown, t-tests are not appropriate and data should be compared via ANOVA with a post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons (eg. Figs 1-1, 2. 2-1, 3, 3-1, etc).

Experimental:

1. Please show data for the responses of the triple-Tetx line (AWB ASK AWC) in the larval stage since the individual ablations have no effect in even the adult stage.

2. Can the tom-1 data be recapitulated with for instance pkc-1gf?

3. For Figure 5D, the n for the ASK-Tom1 is much smaller compared to the n shown for other data. A power analysis might be useful here to determine if you are underpowered.

References

- Albrecht DR, Bargmann CI (2011) High-content behavioral analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans in precise spatiotemporal chemical environments. Nat Methods 8:599–605. 10.1038/nmeth.1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton S, Ignell R, Hansson BS (2002) Developmental changes in the structure and function of the central olfactory system in gregarious and solitary desert locusts. Microsc Res Tech 56:281–291. 10.1002/jemt.10032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI (2006). Chemosensation in C. elegans. WormBook; 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR (1993) Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans. Cell 74:515–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MR, De Lorme KC, Figueira RJ, Kashy DA, Sisk CL (2013) Adolescent gain in positive valence of a socially relevant stimulus: engagement of the mesocorticolimbic reward circuitry. Eur J Neurosci 37:457–468. 10.1111/ejn.12058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beverly M, Anbil S, Sengupta P (2011) Degeneracy and neuromodulation among thermosensory neurons contribute to robust thermosensory behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci 31:11718–11727. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1098-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ (2008) The social brain in adolescence. Nat Rev Neurosci 9:267–277. 10.1038/nrn2353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77:71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun AJ, Tong A, Pokala N, Fitzpatrick JA, Sharpee TO, Chalasani SH (2015) Neural mechanisms for evaluating environmental variability in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuron 86:428–441. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani SH, Chronis N, Tsunozaki M, Gray JM, Ramot D, Goodman MB, Bargmann CI (2007) Dissecting a circuit for olfactory behaviour in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 450:63–70. 10.1038/nature06292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani SH, Kato S, Albrecht DR, Nakagawa T, Abbott LF, Bargmann CI (2010) Neuropeptide feedback modifies odor-evoked dynamics in Caenorhabditis elegans olfactory neurons. Nat Neurosci 13:615–621. 10.1038/nn.2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou JH, Bargmann CI, Sengupta P (2001) The Caenorhabditis elegans odr-2 gene encodes a novel Ly-6-related protein required for olfaction. Genetics 157:211–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis N, Zimmer M, Bargmann CI (2007) Microfluidics for in vivo imaging of neuronal and behavioral activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Methods 4:727–731. 10.1038/nmeth1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann D, Knoll LJ, Blakemore SJ (2015) Adolescence as a sensitive period of brain development. Trends Cogn Sci 19:558–566. 10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara M, Aoyama I, Hino T, Teramoto T, Ishihara T (2016) Gonadal maturation changes chemotaxis behavior and neural processing in the olfactory circuit of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol 26:1522–1531. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.04.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden JW, Riddle DL (1982) A pheromone influences larval development in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 218:578–580. 10.1126/science.6896933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden JW, Riddle DL (1984) The Caenorhabditis elegans dauer larva: developmental effects of pheromone, food, and temperature. Dev Biol 102:368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracheva EO, Burdina AO, Touroutine D, Berthelot-Grosjean M, Parekh H, Richmond JE (2007) Tomosyn negatively regulates both synaptic transmitter and neuropeptide release at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. J Physiol 585:705–709. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JM, Hill JJ, Bargmann CI (2005) A circuit for navigation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:3184–3191. 10.1073/pnas.0409009101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SE, Beverly M, Russ C, Nusbaum C, Sengupta P (2010) A cellular memory of developmental history generates phenotypic diversity in C. elegans. Curr Biol 20:149–155. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G, Shen Y, Ha H, Donato A, Wallis S, Zhang X, Zhang Y (2014) Dissecting the signaling mechanisms underlying recognition and preference of food odors. J Neurosci 34:9389–9403. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0012-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Tong XJ, Kaplan JM (2013) UNC-13L, UNC-13S, and Tomosyn form a protein code for fast and slow neurotransmitter release in Caenorhabditis elegans. Elife 2:e00967. 10.7554/eLife.00967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause ET, Naguib M (2015) Zebra finch males compensate in plumage ornaments at sexual maturation for a bad start in life. Front Zool 12: Suppl 1: S11. 10.1186/1742-9994-12-S1-S11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsch J, Flavell SW, Liu Q, Gordus A, Albrecht DR, Bargmann CI (2015) A circuit for gradient climbing in C. elegans chemotaxis. Cell Rep 12:1748–1760. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsch J, Ventimiglia D, Bargmann CI, Albrecht DR (2013) High-throughput imaging of neuronal activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E4266–42E4273. 10.1073/pnas.1318325110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinwand SG, Chalasani SH (2013) Neuropeptide signaling remodels chemosensory circuit composition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Neurosci 16:1461–1467. 10.1038/nn.3511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinwand SG, Yang CJ, Bazopoulou D, Chronis N, Srinivasan J, Chalasani SH (2015) Circuit mechanisms encoding odors and driving aging-associated behavioral declines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Elife 4:e10181 10.7554/eLife.10181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C, Fire A (1995) DNA transformation. Methods Cell Biol 48:451–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrulis A (2009) Neural mechanisms of individual and sexual recognition in Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus). Behav Brain Res 200:260–267. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD, Parfitt DB, Richardson HN, Sisk CL (1998) Pheromones elicit equivalent levels of Fos-immunoreactivity in prepubertal and adult male Syrian hamsters. Horm Behav 34:48–55. 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarro EC, Rosen MJ, Sanes DH (2011) Taking advantage of behavioral changes during development and training to assess sensory coding mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1225:142–154. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterlee JS, Sasakura H, Kuhara A, Berkeley M, Mori I, Sengupta P (2001) Specification of thermosensory neuron fate in C. elegans requires ttx-1, a homolog of otd/Otx. Neuron 31:943–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavo G, Benfenati F, Poulain B, Rossetto O, Polverino de Laureto P, DasGupta BR, Montecucco C (1992) Tetanus and botulinum-B neurotoxins block neurotransmitter release by proteolytic cleavage of synaptobrevin. Nature 359:832–835. 10.1038/359832a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KM, Zehr JL, Salas-Ramirez KY, Sisk CL (2009) Testosterone programs adult social behavior before and during, but not after, adolescence. Endocrinology 150:3690–3698. 10.1210/en.2008-1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta P, Colbert HA, Bargmann CI (1994) The C. elegans gene odr-7 encodes an olfactory-specific member of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Cell 79:971–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims JR, Ow MC, Nishiguchi MA, Kim K, Sengupta P, Hall SE (2016) Developmental programming modulates olfactory behavior in C. elegans via endogenous RNAi pathways. Elife 5 10.7554/eLife.11642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR (1977) Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 56:110–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN (1983) The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 100:64–119. 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Thiele TR, Faumont S, Ezcurra M, Lockery SR, Schafer WR (2008) Functional asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans taste neurons and its computational role in chemotaxis. Nature 454:114–117. 10.1038/nature06927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi G, Uozumi T, Kiriyama K, Kamizaki T, Hirotsu T (2014) Screening of odor-receptor pairs in Caenorhabditis elegans reveals different receptors for high and low odor concentrations. Sci Signal 7:ra39. 10.1126/scisignal.2005136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troemel ER, Kimmel BE, Bargmann CI (1997) Reprogramming chemotaxis responses: sensory neurons define olfactory preferences in C. elegans. Cell 91:161–169. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80399-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida O, Nakano H, Koga M, Ohshima Y (2003) The C. elegans che-1 gene encodes a zinc finger transcription factor required for specification of the ASE chemosensory neurons. Development 130:1215–1224. 10.1242/dev.00341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S (1973) Chemotaxis by the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: identification of attractants and analysis of the response by use of mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 70:817–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wes PD, Bargmann CI (2001) C. elegans odour discrimination requires asymmetric diversity in olfactory neurons. Nature 410:698–701. 10.1038/35070581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S (1986) The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 314:1–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Hirotsu T, Tagawa T, Oda S, Wakabayashi T, Iino Y, Ishihara T (2012) Odour concentration-dependent olfactory preference change in C. elegans. Nat Commun 3:739 10.1038/ncomms1750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahratka JA, Williams PD, Summers PJ, Komuniecki RW, Bamber BA (2015) Serotonin differentially modulates Ca2+ transients and depolarization in a C. elegans nociceptor. J Neurophysiol 113:1041–1050. 10.1152/jn.00665.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaslaver A, Liani I, Shtangel O, Ginzburg S, Yee L, Sternberg PW (2015) Hierarchical sparse coding in the sensory system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:1185–1189. 10.1073/pnas.1423656112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie showing the switching of the flow patterns between “stimulus on” and “stimulus off” in the novel L3-microfluidic device. A stimulus change occurs at 2 s in clip. Movie is sped up 30×.