Abstract

Autophagy is the major intracellular degradation system by which cytoplasmic materials are delivered to and degraded in the vacuole/lysosome in eukaryotic cells. MoAtg14 in M. oryzae, a hitherto uncharacterized protein, is the highly divergent homolog of the yeast Atg14 and the mammal BARKOR. The MoATG14 deletion mutant exhibited collapse in the center of the colonies, poor conidiation and a complete loss of virulence. Significantly, the ΔMoatg14 mutant showed delayed breakdown of glycogen, less lipid bodies, reduced turgor pressure in the appressorium and impaired conidial autophagic cell death. The autophagic process was blocked in the ΔMoatg14 mutant, and the autophagic degradation of the marker protein GFP-MoAtg8 was interrupted. GFP-MoAtg14 co-localized with mCherry-MoAtg8 in the aerial hypha. In addition, a conserved coiled-coil domain was predicted in the N-terminal region of the MoAtg14 protein, a domain which could mediate the interaction between MoAtg14 and MoAtg6. The coiled-coil domain of the MoAtg14 protein is essential for its function in autophagy and pathogenicity.

Magnaporthe oryzae, the causal agent of rice blast, has been chosen as a model to study the interaction between fungi and plants. Common to many other plant pathogenic fungi, M. oryzae elaborates a signature penetration structure, the appressorium, to infect its host1,2,3. The whole infectious cycle of M. oryzae, from surface recognition, adherence, and appressorium formation to infectious growth and pathogenicity, is closely related to signal transduction pathways and protein degradation processes. The typical signal transduction pathways, including mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), and calcium signal transduction pathways4,5,6,7, and the protein degradation processes, including autophagy8,9,10, ubiquitin mediated protein degradation11,12,13 and calpains14,15, have been confirmed to play significant roles in cell cycling, cellular differentiation and pathogenesis of M. oryzae.

Autophagy is an intracellular degradation system that delivers cytoplasmic materials to the lysosome/vacuole during development and in response to nutrient stress in eukaryotic cells16. The autophagy process was verified as an essential catabolic process that plays important roles in cell stress management and nutrient homeostasis. The differentiation, cell vitality, and infectious structures are impaired when the autophagy process is blocked. Current studies have shown that the Atg proteins required for autophagy constitute the following five functional groups: (i) the Atg1 kinase complex (Atg1-13-17-29-31), (ii) the Atg9 membrane protein recycling system, (iii) the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) complex (Atg6-Atg14-Vps15-Vps34) (hereafter, PI3-K indicates the class III PI3-K), (iv) the Atg12-Atg5-Atg16 protein conjugation system, and (v) the Atg8 lipid conjugation system16,17. For the past two decades, the core proteins of every autophagy group have been verified to function in M. oryzae, for example, MoAtg1 in the Atg1 kinase complex18, MoAtg9 in the Atg9 membrane protein recycling system19, MoAtg5 in the conjugation system20, and MoAtg4 and MoAtg8 in the lipid conjugation system8,21,22. Extensive research has been performed on other plant pathogenic fungi, including Fusarium23,24,25, Colletotrichum26,27,28, Ustilago29,30, and Verticillium31. However, there are few studies of the PI3-K complex in plant pathogenic fungi.

PI3-K is essential for both autophagy and vacuolar protein sorting in yeast and mammals32,33,34. Atg14 is the autophagy-specific subunit of the PI3-K complex and a key factor in determining the function of the PI3-K complex. Atg14 is present on the preautophagosomal structure (PAS) and is thought to function at an early stage of autophagosome formation. Initially, Atg14 was only described in yeast species35. Recently, a protein with an extremely low similarity to yeast Atg14 was identified in humans and named ATG14/ATG14L/BARKOR36,37. In M. oryzae, a conventional BLAST database search failed to identify a homolog of Atg14. Using a combination of Pfam domain analysis, position specific iterated (PSI)-BLAST and the pattern hit-initiated basic local alignment search tool (PHI-BLAST), MoAtg14 was identified in the database of M. oryzae. The conserved coiled-coil protein MGG_03698, designated MoAtg14 in the genome of M. oryzae, was shown to have very weak similarity to ScAtg14 and HsAtg14.

To date, no experimental evidence has emerged to explain the functions of the homolog of Atg14 in M. oryzae. In our research, we found that MoAtg14 was conserved in the filamentous ascomycetes. Deletion of MoAtg14 resulted in defects in conidiation, breakdown of glycogen and lipid bodies, turgor pressure of appressoria, pathogenicity, and the autophagy process. Subcellular localization and microscopic examination indicated that MoAtg14 is present on the PAS and plays key roles at the stage of autophagosome formation. The localization of MoAtg8 was impaired in the MoAtg14 deletion mutant. The conserved coiled-coil domain of MoAtg14 plays critical roles in M. oryzae.

Results

Identification of MoAtg14 in M. oryzae

Pfam domain analysis of the M. oryzae proteome was used to identify the proteins. The integrated module of the Pfam domain was searched with the CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen, Germany) using the default parameters. The Pfam database used in the analysis was version 27. MGG_03698 and MGG_13375 were found to contain the conserved domain PF10186. We reanalyzed protein databases at the NCBI by position specific iterated (PSI-BLAST) and pattern hit-initiated basic local alignment search tool (PHI-BLAST) using both yeast and human Atg14. The conserved coiled-coil protein MGG_03698 in the genome of M. oryzae was confirmed to have weak similarity to ScAtg14 and HsAtg14 and was designated MoAtg14. The other protein, MGG_13375, showed more similarity to mammalian UVRAG proteins (a counterpart of the mammalian Vps38)37,38, implying that MGG_13375 might represent the fungal ortholog of Vps38.

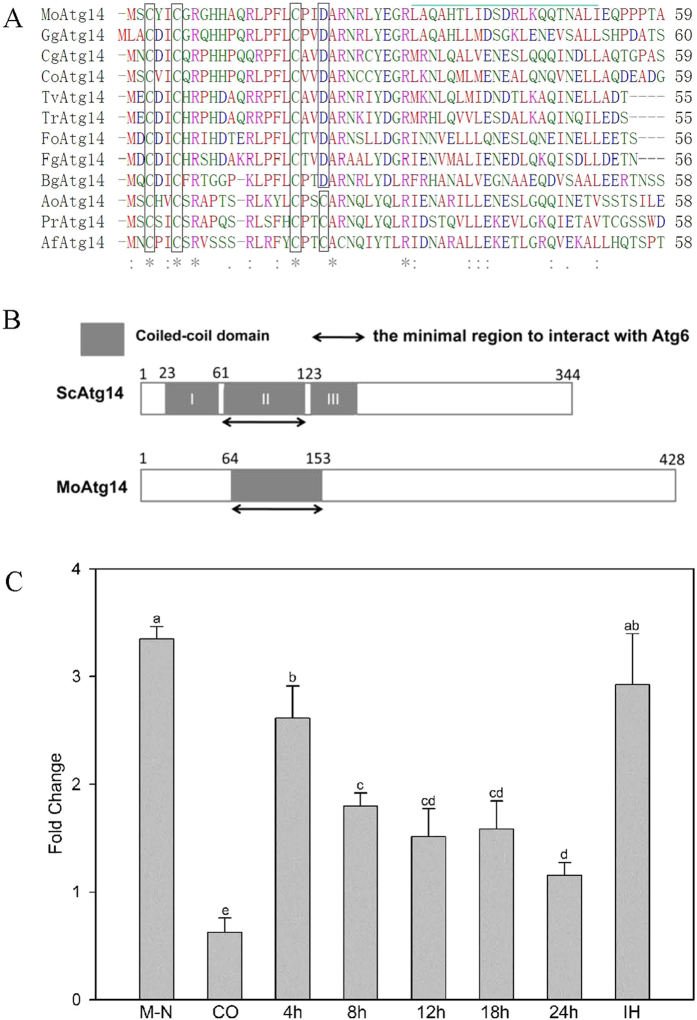

Analysis of the domain of MoAtg14 showed that it contains a conserved Cys-rich motif at its N-terminus (Fig. 1A). The motif is also present in yeast and human Atg14, and it displays high levels of similarity to homologs in other filamentous ascomycetes, including Gaeumannomyces graminis (55% identity), Colletotrichum orbiculare (50% identity), Fusarium graminearum (46% identity) and Blumeria graminis (39% identity). To verify the high similarity of MoAtg14 with Atg14 in other ascomycetes, we selected F. graminearum Atg14 (FgAtg14) and Trichoderma reesei Atg14 (TrAtg14) to complement the ΔMoatg14 mutant. Reintroduction of FgAtg14 or TrAtg14 to the mutant, the defects of the ΔMoatg14 mutant could be recovered completely (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

(A) The amino acid sequence of the N-terminal motif containing the conserved cysteine residues in the ascomycetes fungi. The conserved cysteine residues are in the box. The green line indicates the start of the conserved coiled-coil region. GgAtg14, accession No. XP_009224438; CgAtg14, accession No. EQB48915; CoAtg14, accession No. ENH80301; TvAtg14, accession No. XP_013959553; TrAtg14, accession No. XP_006966865; FoAtg14, accession No. EMT61395; FgAtg14, accession No. XP_011316371; BgAtg14, accession No. EPQ63265; AoAtg14, accession No. BAE65502; AfAtg14, accession No. XP_747209; PrAtg14, accession No. CDM36188. (B) The domains of the yeast ScAtg14 and M. oryzae MoAtg14. Boxes in grey indicate the coiled-coil domains. (C) The expression profiles of the MoATG14 gene in development, pathogenicity and starvation stress. qRT-PCR assays were carried out with RNA samples obtained from different stages of the wild-type strain Guy11, including vegetative hyphae, conidia (CO), appressoria, invasive hyphae (IH) and nitrogen starved hyphae (MM-N). Gene expression levels were normalized using the β-tubulin gene as an internal standard. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results, and the error bars represent the standard deviations of three replicates (P < 0.01). Different letters indicate a significant difference.

It has been reported that three predicted coiled-coil domains exist in the N-terminal half of yeast Atg14. These coiled-coil domains are sufficient to support the autophagic ability as revealed by deletion analysis of yeast Atg14. The second coiled-coil domain of yeast Atg14 interacted with Atg635,39. However, only one coiled-coil domain exists in the N-terminus of MoAtg14 in M. oryzae as predicted by COILS (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/COILS_form.html) (Figs 1B and S2). Our research revealed the detailed functions of MoAtg14, as described below. In addition, MoVps38 contains a coiled-coil domain (Figure S3). Unfortunately, we were not able to isolate a null mutant of MoVps38.

To determine the expression profiles of the MoATG14 gene during development (in vegetative hyphae, conidia, and appressoria), pathogenicity (in infective hyphae) and starvation stress (in nitrogen starved hyphae), expression was evaluated using qRT-PCR assays (Fig. 1C). Compared with the expression level of MoATG14 in vegetative hyphae, in the nitrogen starved hyphae, the expression level was more than 3-fold higher. In addition, the expression level of MoATG14 was more than 2-fold higher in 4 h -appressoria and invasive hyphae than in vegetative hyphae.

Deletion of MoATG14 in M. oryzae

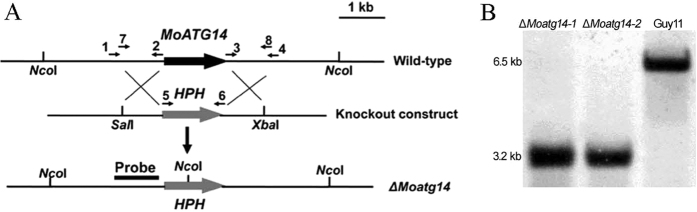

To determine the biological functions of MoATG14 in M. oryzae, we constructed a deletion mutant by targeted gene replacement using ATMT (Fig. 2A). Southern blot assays were performed to confirm single-copy genomic integration and exclude additional ectopic integrations. An approximately 3.2 kb band was detected in ΔMoatg14 mutants, in contrast to an approximately 6.5 kb band in the wild-type strain Guy11 (Fig. 2B). Two ΔMoatg14 mutants showed comparable phenotypes, and ΔMoatg14-1 was chosen for further studies. Complementation assays of ΔMoatg14-1 were carried out, and the transformant Moatg14c, which contained a full-length gene copy of MoATG14, was selected for further studies.

Figure 2. Targeted gene deletion of MoATG14 in M. oryzae.

(A) The MoATG14 locus and gene deletion vector. Arrows 1–8 indicate the primers ATG14up-1/2, ATG14dn-1/2, HPH-1/2 and ATG14-N1/2. (B) Southern blot analysis of ΔMoatg14 mutants 1 and 2, and the wild-type strain Guy11. Genomic DNA was digested with NcoI and separated on a 0.7% agarose gel. The DNA was hybridized with the probe (indicated in A) amplified from genomic DNA of Guy11.

MoAtg14 is required for hyphal development, conidiogenesis and pathogenicity

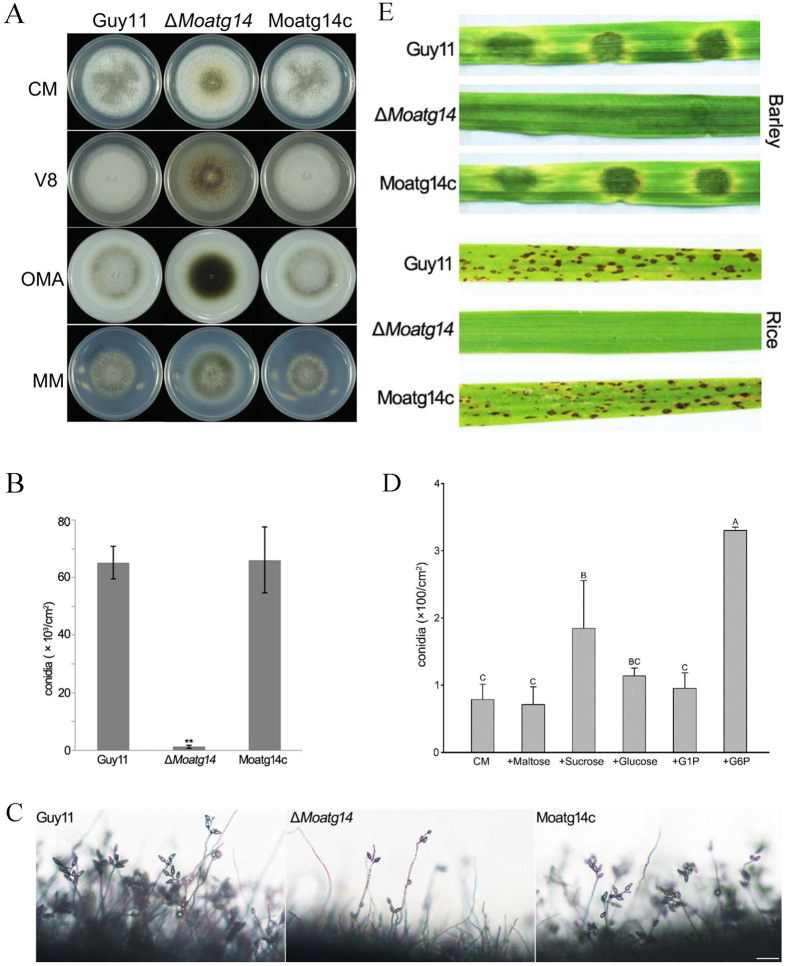

On CM plates, the ΔMoatg14 mutant showed vegetative growth similar to that of the wild-type strain Guy11, and the complemented strain Moatg14c. However, the ΔMoatg14 mutant showed sparse hyphae with necrotic centrality, especially on the V8 and OMA media, in contrast to the dense hyphae of Guy11 and Moatg14c (Fig. 3A). On a 10-day-old CM plate, the number of conidia produced by the ΔMoatg14 mutant was only 1/50 of the number produced by Guy11 (Fig. 3B). Microscopic examination revealed that small numbers of conidia were observed on the conidiophores of the ΔMoatg14 mutant at 24 h post-conidial induction after an 8-day incubation (Fig. 3C). These observations suggested that the MoATG14 gene plays key roles in hyphal development and conidiogenesis.

Figure 3. Characteristics of M. oryzae strains.

(A) Guy11, the ΔMoatg14 mutant, and the complemented strain Moatg14c were grown on CM, V8, OMA, and MM medium for 8 days. (B) Few conidia were produced by the ΔMoatg14 mutant, in contrast to Guy11 and Moatg14c. Error bars represent one standard deviation (P < 0.01). Different letters indicate a significant difference in the conidiation of the ΔMoatg14 mutant, Guy11, and Moatg14c. (C) Development of conidia on conidiophores observed under cover slips with a light microscope 24 h after induction of conidiation. Few conidia developed in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. Scale bar = 50 μm. (D) Conidiation in the ΔMoatg14 mutant grown on CM medium and CM medium supplemented with 10 g/L maltose, 6.25 g/L sucrose, 10 g/L glucose, 1 mM G1P and 0.5 mM G6P. Error bars represent one standard deviation (P < 0.01). Different letters indicate a significant difference. (E) The MoAtg14 deletion mutant is nonpathogenic. Disease symptoms on cut leaves of barley inoculated with mycelial plugs from Guy11, the ΔMoatg14 mutant, and Moatg14c. Typical leaves were photographed 4 days after inoculation. Two-week-old rice seedlings were inoculated by spraying with 1 × 105 conidia/ml conidia suspensions from Guy11, the ΔMoatg14 mutant, and Moatg14c. Lesion formation on the rice leaves was evaluated 7 days after inoculation.

It has been reported that alternate carbon sources (mostly sugars) can suppress the conidiation defects of the ΔMoatg8 mutant22. To explore the effects of alternate carbon sources on the conidiation capability of the ΔMoatg14 mutant, the conidia of the mutant were collected and counted after 10 days on complete medium (CM) supplemented with additional maltose, sucrose, glucose, glucose 1-phosphate (G1P), or glucose 6-phosphate (G6P). As expected, the addition of G6P significantly restored conidiation in the ΔMoatg14 mutant (Fig. 3D). There were 3 times more conidia on CM supplemented with G6P than on CM. In addition, the number of conidia on CM supplemented with sucrose was approximately 2-fold that on CM. These data confirmed that alternate sugar sources could relieve the conidiation defects resulting from the loss of autophagy.

In infection assays with two susceptible hosts (rice and barley), the ΔMoatg14 mutant failed to penetrate either host. Disease symptoms were not observed when mycelial plugs of ΔMoatg14 were inoculated onto barley. In contrast, the wild-type strain Guy11 and the complemented strain Moatg14c, induced susceptible lesions. Similarly, no spindle-shaped lesions were observed on rice inoculated with a ΔMoatg14 conidial suspension (1 × 105 conidia/ml). These data indicated that the MoATG14 gene is important for plant infection (Fig. 3E).

MoAtg14 is required for glycogen mobilization, quantity of lipid bodies, and the turgor pressure of appressoria

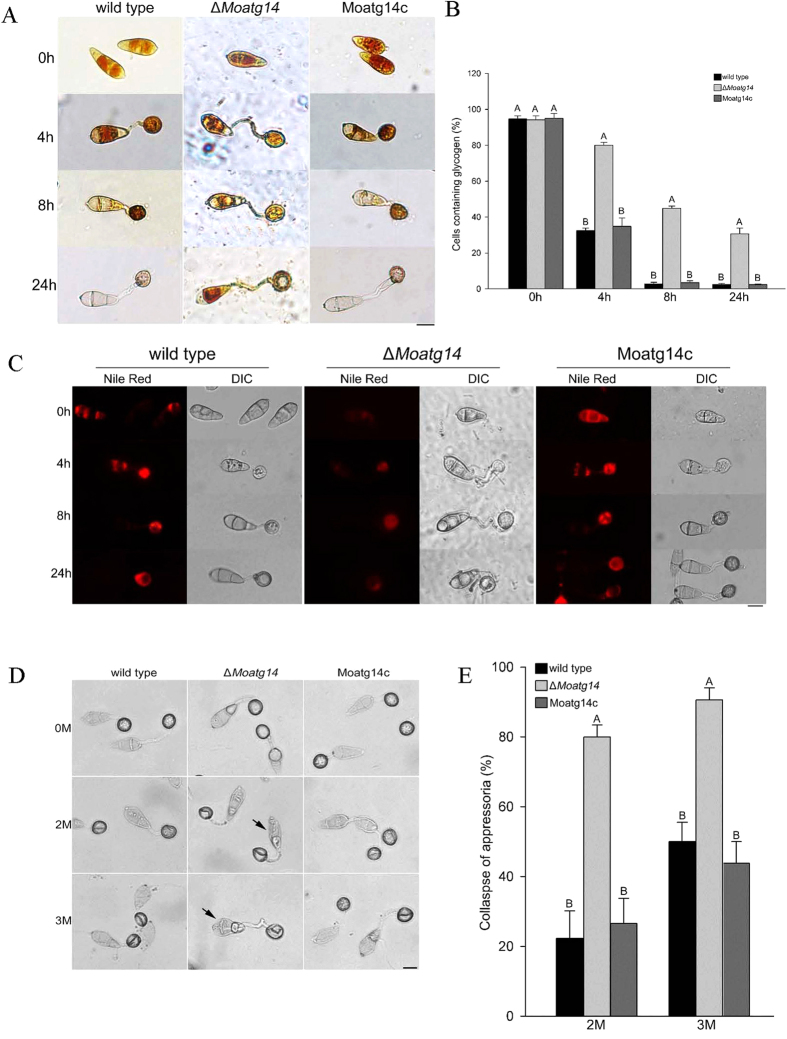

Glycogen and lipids are the most abundant storage products in M. oryzae conidia. Glycogen is rapidly degraded during conidial germination, and lipid bodies are transported to the developing appressoria and degraded at the onset of turgor generation40. Previous studies showed that the breakdown of glycogen and lipid bodies was delayed in the autophagy-deficient mutants (ΔMoatg1, ΔMoatg4, ΔMoatg5, ΔMoatg8, and ΔMoatg9)8,18,19,20,21,22. Therefore, the cellular distribution of glycogen and lipid bodies was examined during appressorium development in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. The wild-type strain and the ΔMoatg14 mutant show similar distributions of glycogen in conidia (Fig. 4A, 0 h). With the development of conidia, the glycogen in the conidia was degraded gradually in the wild-type strain. After 24 h, a very small proportion of the wild-type conidia contained glycogen. In contrast, a high proportion of the ΔMoatg14 conidia contained glycogen from the stage of the germ tube to mature appressoria (Fig. 4A). At 24 h, 30% of the cells of the ΔMoatg14 conidia contained glycogen compared to 2% of the cells of the wild-type conidia (Fig. 4B). These data indicated that the breakdown of glycogen was significantly retarded in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. Next, we investigated the distribution of lipid bodies by Nile red staining in the ΔMoatg14 mutant from conidia to appressoria (Fig. 4C). The ΔMoatg14 mutant showed faint fluorescence in contrast to the bright fluorescence of the wild type.

Figure 4. Conidia of the wild-type strain, the ΔMoatg14 mutant, and the complemented mutant Moatg14c were allowed to form appressoria on plastic coverslips at 0 h, 4 h, 8 h and 24 h after inoculation.

(A) Cellular distribution of glycogen. Samples were stained with KI/I2 solution. Microscopically, the glycogen appears as dark brown deposits. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) The proportion of the conidial cells containing glycogen stained by KI/I2 solution during appressorium development in the Guy11, the ΔMoAtg14 mutant, and Moatg14c. Error bars represent one standard deviation (P < 0.01). Different letters indicate a significant difference. (C) Cellular distribution of lipid droplets. Samples were stained with Nile red and observed in the dark with UV epifluorescence. The lipid droplets show a red signal fluorescence. Scale bar = 10 μm. (D) Collapse of appressoria. Conidia were allowed to form appressoria on plastic coverslips 24 h after inoculation, and the collapsed appressoria were assessed after exposure to 2 M or 3 M glycerol solution for ten minutes. Arrows indicate the collapsed portions of the conidia. Scale bar = 10 μm. (E) The turgor pressure of the appressoria was measured by incipient cytorrhysis assays. The proportion of the collapsed appressoria after exposure to 2 M or 3 M glycerol solution for ten minutes are shown. Error bars represent one standard deviation (P < 0.01). Different letters indicate a significant difference.

Glycogen mobilization was delayed significantly and lipid bodies were reduced in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. We examine the turgor pressure of the ΔMoatg14 appressoria using the incipient cytorrhysis assays. As shown in Fig. 4D, the appressoria of ΔMoatg14 severely collapsed in 2 M glycerol. In the ΔMoatg14 mutant, 80% of the appressoria collapsed at 24 h compared to 22% and 26% of the appressoria of the wild-type and complemented strains, respectively. In 3 M glycerol, a high proportion of the ΔMoatg14 appressoria remained severely collapsed (Fig. 4D,E). In summary, the turgor pressure of the ΔMoatg14 appressoria was significantly lower than in the wild-type or the complemented strain.

MoAtg14 is required for autophagy and conidial autophagic cell death

In yeasts, Atg14 is a key player in orchestrating autophagy35. To determine whether the loss of MoATG14 affects autophagy in M. oryzae, vacuoles of hyphal cells were examined with starvation induction assays. When cultured in sterile distilled water in the presence of 2 mM PMSF for 4 h, no autophagic bodies were detected in the lumen of vacuoles in the ΔMoatg14 mutant hyphae, whereas a large number of autophagic bodies existed in the vacuole lumen of Guy11 and Moatg14c cultures (Fig. 5A).

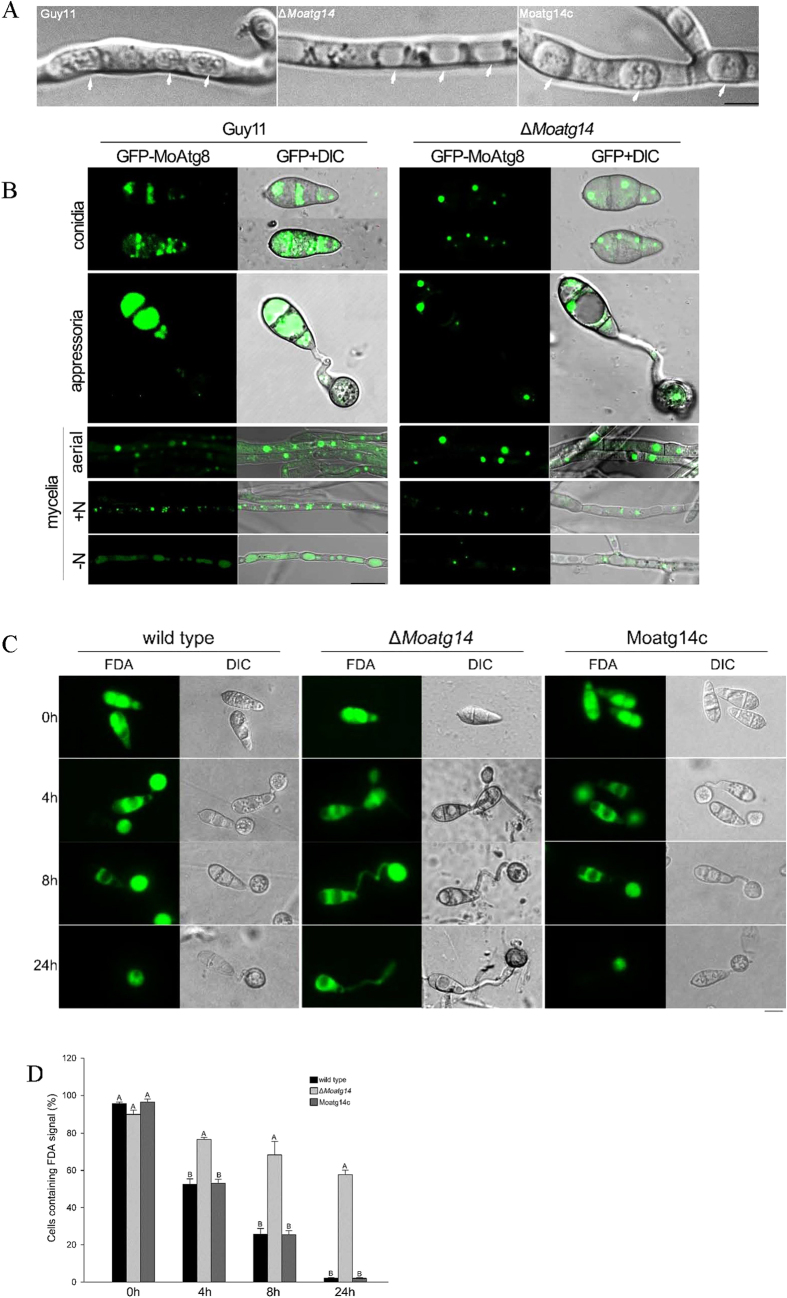

Figure 5. Autophagy was blocked in the ΔMoatg14 mutant.

(A) Autophagy was triggered in the starved mycelia. Numerous autophagic bodies were detected in the vacuoles of Guy11 and Moatg14c under starvation conditions. The mycelia were treated with 4 mM PMSF under nitrogen starvation for 4 h. No autophagic bodies were evident in ΔMoatg14 mutant vacuoles under the same conditions. Arrows indicate the vacuoles. (B) Normal GFP-MoAtg8 localization was impaired in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. Conidia were collected from the Guy11 and ΔMoAtg14 strains expressing GFP-MoAtg8. Appressoria: 1 × 104 conidia of Guy11 and ΔMoAtg14 expressing GFP-MoAtg8 were inoculated on the hydrophobic cover slip and incubated for 8 h. Mycelia: aerial hyphae of Guy11 and ΔMoAtg14 expressing GFP-MoAtg8. The strains Guy11 and ΔMoAtg14 expressing GFP-MoAtg8 were grown in liquid CM medium at 25 °C for 48 h (N+), and shifted to liquid MM-N medium with 4 mM PMSF for 4 h (N−). Scale bar = 10 μm. (C) Conidial autophagic cell death assays of strains. The conidial cells of the wild-type strain and Moatg14c showed conidial autophagic cell death during appressoria development. The ΔMoAtg14 mutant had defects in conidial autophagic cell death. (D) The proportion of the conidial cells containing an FDA signal during the development of the Guy11, ΔMoAtg14 and Moatg14c strains. Error bars represent one standard deviation (P < 0.01). Different letters indicate a significant difference.

To identify other functions of MoATG14 in autophagy, GFP-MoAtg8 trafficking assays were performed. Under normal conditions in the wild-type, Guy11, GFP-MoAtg8 was localized to punctate structures that were proximal to the vacuoles, whereas in nitrogen starvation conditions, GFP fluorescence showed an even distribution in the lumen of the vacuoles (Fig. 5B, Guy11). In contrast, in the ΔMoatg14 mutant, GFP-MoAtg8 failed to localize in the vacuoles upon nitrogen starvation (Fig. 5B, ΔMoatg14). Accumulation of GFP in vacuoles was absent in every developmental phase of ΔMoAtg14, including conidia, appressoria and mycelia (Fig. 5B, ΔMoatg14). Multiple punctate structures of GFP-MoAtg8 were assembled into larger dots proximal to the vacuoles, and no green signals were observed in the vacuole lumen after 4 h of nitrogen starvation in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. Conversely, GFP accumulated in the vacuoles of the wild-type, Guy11, from conidia to mature appressoria (Fig. 5B, Guy11). The results indicated that GFP-MoAtg8 trafficking was impaired in the ΔMoatg14 mutant.

Because ΔMoatg14 failed to deliver GFP-Atg8 to the vacuoles upon nitrogen starvation, GFP-MoAtg8 proteolysis assays were performed to monitor the autophagy process. Under normal conditions, the 41-kDa GFP-MoAtg8 fusion band was detected in anti-GFP western blotting in the wild-type, Guy11. When cultured hyphae were shifted to starvation conditions, the levels of free GFP increased with time, apparently at the expense of full-length GFP-MoAtg8. In contrast, only full-length GFP-MoAtg8 was detected in the ΔMoatg14 mutant (Figure S4). The proteolysis of GFP-MoAtg8 was completely prevented in the ΔMoatg14 mutant.

All these data confirmed that the autophagy pathway was blocked in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. Next, we examined the conidial cell death in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. The cells were strained by fluorescein diacetate (FDA), a viability stain for cells. The green fluorescence proved that the cells were still alive. As shown in Fig. 5D, a high proportion of the cells of the ΔMoatg14 conidia showed green fluorescence after 24 hpi on the plastic coverslip (Fig. 5C,D). In contrast, very few cells of the wild-type conidia showed fluorescence after 24 hpi on the plastic coverslip. These results indicated that the ΔMoatg14 mutant did not show conidial cell death.

MoAtg14 is present in PAS

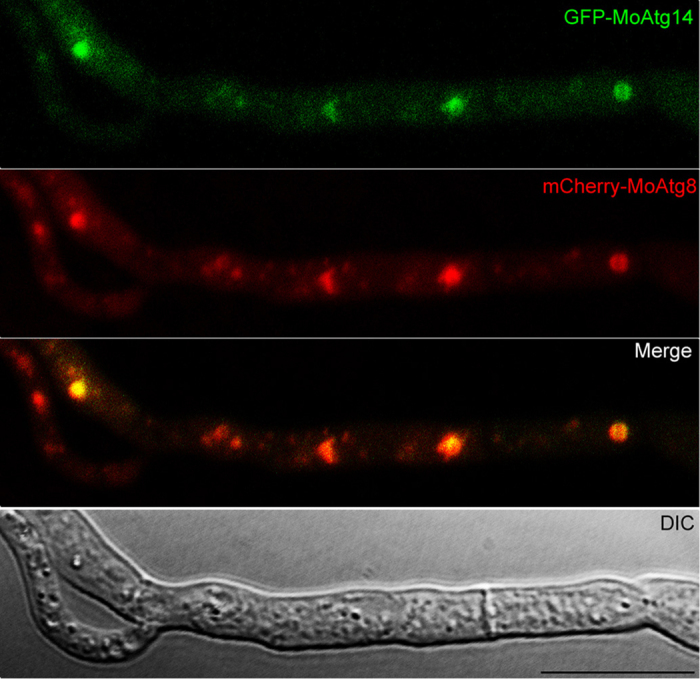

To determine the location of MoAtg14, we transformed the GFP-MoAtg14 fusion expression vector into the ΔMoatg14 mutant. In the transformants, the defects of ΔMoatg14 were complemented, which indicated that the GFP-MoATG14 fusion protein is functional (data not shown). Faint fluorescence could be detected in the cytoplasm of conidia, mycelia and appressoria (Figure S5). However, in aerial hyphae, which are without external nutrients, GFP-MoAtg14 appeared as punctuate dots. Our previous study showed that mCherry-MoAtg8 localized at multiple PAS sites in M. oryzae19. To investigate the localization of the GFP-MoAtg14 dots, mCherry-MoAtg8 was transformed into the mutant containing GFP-MoAtg14. We found that puncta of GFP-MoAtg14 co-localized with mCherry-MoAtg8, leaving other green signals distributed throughout the entire cytoplasm (Fig. 6). The co-localization of GFP-MoAtg14 and mCherry-MoAtg8 suggested that MoAtg14 is present in the PAS in M. oryzae.

Figure 6. Co-localization of GFP-MoAtg14 and mCherry-MoAtg8. Scale bar = 10 μm.

The coiled-coil domain of MoAtg14 plays crucial roles in M. oryzae

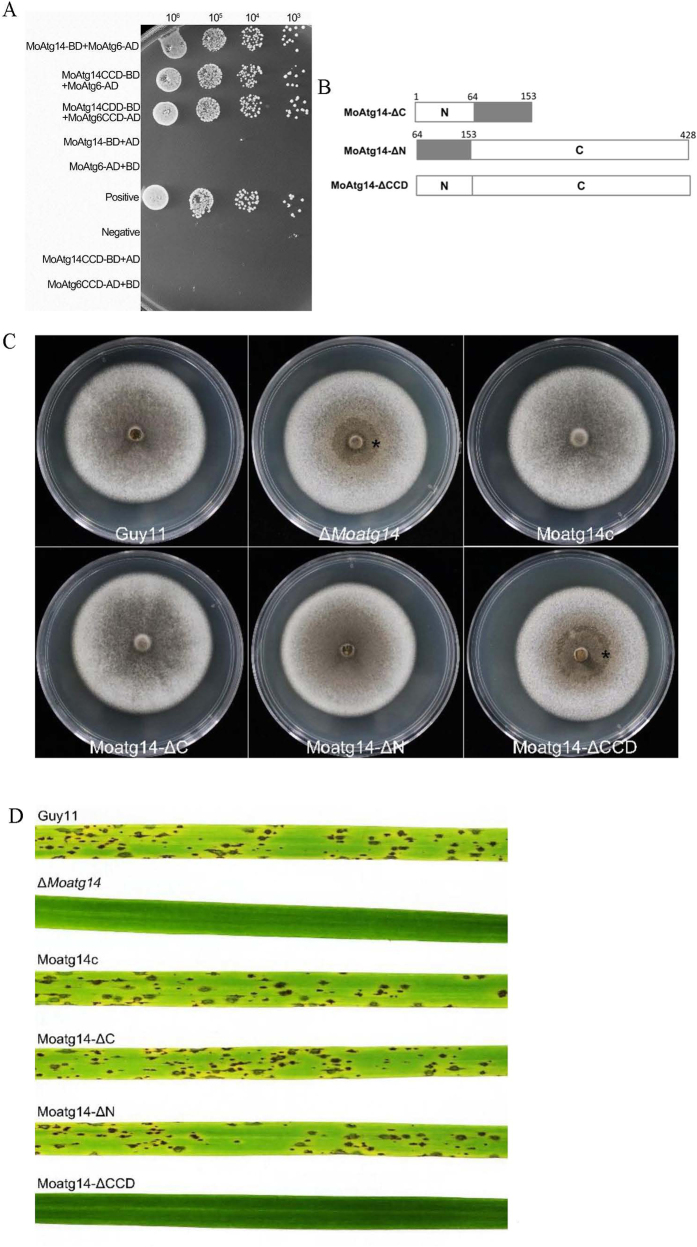

As previously described, Atg14/Barkor physically interacts with Atg6/Beclin1 in yeasts and mammals37,38. To determine whether MoAtg14 interacts with MoAtg6 in M. oryzae, yeast two-hybrid assays were performed. The results showed that yeast cells containing the full-length MoAtg14 (prey) and MoAtg6 (bait) on two-hybrid plasmids could grow well on the Ade-His-Leu-Trp-minus-selective plates (Fig. 7A). The coiled-coil domain of MoAtg14 (MoAtg1464–153) was cloned into the pGADT7 vector to generate the prey vector pAD-MoAtg1464–153. Cells containing pAD-MoAtg1464–153 could grow on the Ade-His-Leu-Trp-minus selective plates in combination with the full-length MoAtg6 (BD) vector. The N-terminus (MoAtg141–73) and C-terminus (MoAtg14144–428) were cloned into the pGADT7 vector and co-transformed into AH109 cells. However, the cells could not grow on the Ade-His-Leu-Trp-minus selective plates in combination with the full-length MoAtg6 (bait) vector (Fig. 7A). We obtained similar results when we used the coiled-coil domain of MoAtg6 as bait. The coiled-coil domain of MoAtg6 interacted with the full-length MoAtg14 or MoAtg1464–153. Cells could grow on the Ade-His-Leu-Trp-minus-selective plates. This result indicated that the coiled-coil domain of MoAtg14 was required for the interaction with MoAtg6. The primary function of MoAtg14 is mediated by protein-protein interactions of the coiled-coil domain.

Figure 7.

(A) Yeast two-hybrid assays. The interactions between MoAtg14 and MoAtg14 CCD as bait and MoAtg6 and MoAtg6 CCD as the prey were assessed. Yeast transformants grown on the SD/-Ade/-Leu/-Trp/-His plates were assayed for β-galactosidase activity. (B) Schematic representation of deleted variants of MoAtg14. (C) The coiled-coil domain in MoAtg14 is essential to maintain normal colony morphology. Strains were grown on CM for 10 days. The asterisk indicates the collapse of the colony. (D) The coiled-coil domain in MoAtg14 is essential to maintain normal pathogenicity. Disease symptoms of rice inoculated with 1 × 105 conidia from Guy11, the ΔMoatg14 mutant, Moatg14c, Moatg14-ΔC, Moatg14-ΔN, and Moatg14-ΔCCD. The lesions formed on the rice were photographed 7 days after inoculation.

To investigate the function of the coiled-coil domain of MoAtg14 in M. oryzae, pMoAtg14-ΔN, pMoAtg14-ΔC and pMoAtg14-ΔCCD vectors were constructed to transform into the ΔMoatg14 mutant separately (Fig. 7B). The results showed that the morphology of the colonies, conidiation, pathogenicity and autophagy recovered when we introduced pMoAtg14-ΔN or pMoAtg14-ΔC. However, pMoAtg14-ΔCCD could not recover the defects of the ΔMoatg14 mutant (Fig. 7C,D). The phenotypes of the MoAtg14-ΔCCD mutant were similar to that of the ΔMoatg14 mutant (Fig. 7C,D), which indicated that the coiled-coil domain is the core of MoAtg14.

Discussion

Autophagy has been extensively studied in M. oryzae. In this research, we focused on MoAtg14, an important subunit of the PI3-K complex, which is essential for autophagy. Analysis using a gene knockout indicated that MoAtg14 is essential for autophagy and plays key roles in conidiation, the breakdown of glycogen, numbers of lipid bodies, pathogenicity, conidial autophagic cell death, and autophagosome formation. The predicted coiled-coil domain of MoAtg14 is essential for its function in autophagy and development and is responsible for interaction with MoAtg6. The MoAtg14-ΔCCD mutant lacking the coiled-coil domain had a phenotype similar to that of the ΔMoatg14 mutant. However, the MoAtg14-ΔC and the MoAtg14-ΔN mutants, which expressed truncated MoAtg14 lacking the C-terminal or N-terminal half, showed no obvious defect in colony morphology, conidiogenesis, pathogenicity or autophagic activity.

The sequence identity between MoAtg14 and yeast Atg14 is extremely low. In S. cerevisiae, Δatg14 shows defects in viability and autophagy. To investigate the functional homology between Atg14 and MoAtg14, the complementation vector pYA14 containing the full-length yeast ATG14 was transformed into the ΔMoatg14 mutant to generate the ΔMoatg14::ATG14 strain. Unfortunately, the ΔMoatg14::ATG14 strains showed sparse aerial hyphae on CM medium similar to the mutant ΔMoatg14. In addition, no autophagic bodies accumulated in the vacuoles of the ΔMoatg14::ATG14 strains when it was grown in sterile distilled water (starvation conditions) containing 2 mM PMSF for 4 h (data not show). Yeast Atg14 could not complement the autophagic defects of the ΔMoatg14 mutant. We deduced that Moatg14 may have different biological functions in M. oryzae.

Conidiation is essential for the rice blast fungus to carry out its infection cycle. Conidiation was impaired in many autophagy-deficient mutants, including M. oryzae ΔMoatg1, 4, 5, 8, 99,18,19,21,22, F. graminearum ΔFgatg8 and ΔFgatg1523,25, C. lindemuthianum Δatg1/Δclk128, C. orbiculare Δatg2626, Ustilago maydis Δatg1 and Δatg830. In our present study, ΔMoatg14 showed sparse aerial hyphae and reduced conidiation. These data indicated that autophagy plays key roles in aerial hyphal growth and conidiophore differentiation. It has been reported that sucrose or glucose could restore conidiation of the ΔMoatg8 mutant to a level comparable to the wild type by external supplementation of carbohydrates22. Although external supplementation of carbohydrates, including G6P and sucrose, alleviated the conidiation defects of the ΔMoatg14 mutant, the recovery of the conidiation defects is not comparable to that of the wild type. In yeast, Atg14 is required for membrane trafficking pathways33. In addition, yeast Atg14 could not complement the defects of the ΔMoatg14 mutant. We proposed that MoAtg14 might play other different biological roles beyond autophagy in M. oryzae, such as membrane trafficking pathway and so on. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the additional functions beyond autophagy of MoAtg14 in M. oryzae.

In addition to reduced conidia in ΔMoatg14, there was a loss of pathogenicity. At present, the evidence suggests that delayed degradation of the glycogen, less lipid bodies and reduced turgor pressure result in defects in pathogenicity upon loss of autophagy in M. oryzae10. Our data provide evidence that the reasons for the loss of pathogenicity in ΔMoatg14 are consistent with those for the other autophagy deficient mutants (ΔMoatg1, 4, 5, 8, 9) in M. oryzae.

Atg8 can localize to autophagosomes and be internalized in vacuoles after the fusion of autophagosomes and vacuoles. Autophagy can be visualized directly by fluorescent marker tagged Atg841. A bright punctate structure representing the PAS is observed when the mycelia of the wild-type strain Guy11 expressing GFP-MoAtg8 are grown in nutritious conditions. However, the vacuole lumen is stained with fluorescence, which reflects the induction of autophagy when the same mycelia are starved for 4 h. Under the same starvation conditions, no movement of GFP-MoAtg8 to the vacuolar lumens were observed when autophagy was induced in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. Loss of MoAtg14 prevents MoAtg8 from leaving the PAS structure in M. oryzae. In addition, the GFP-MoAtg8 proteolysis assays in the ΔMoatg14 mutant confirmed the fluorescent visualization of GFP-MoAtg8. No autophagic bodies were observed in the vacuole lumens of the ΔMoatg14 mutant using microscopy assays. These results are in accord with the movement and proteolysis of GFP-MoAtg8 in the ΔMoatg1 mutant, in which the autophagy was fully blocked18,42. It has been reported that most of autophagy-related proteins accumulate at the PAS and generate autophagosomes. Autophagy-related proteins are classified into several different groups at the different steps of the autophagy pathway. MoAtg1 has an effect on the initiation of autophagy and is involved in the building of the PAS. MoAtg14, an autophagy-specific regulator of the PI3-K complex, contributes to autophagosome formation of autophagy and mediates the transfer of other autophagy-related proteins to PAS. In addition to the changes in the GFP-MoAtg8 localization and proteolysis, the ΔMoatg14 mutant showed defects in autophagic cell death. The FDA staining assays showed that many of the ΔMoatg14 conidia contained FDA signals during the appressorial development. Death of the conidia was prevented upon loss of autophagy in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. It has been reported that autophagic cell death is important for fungal developmental biology and pathogenesis8,43. Our data provide evidence that MoAtg14 is an important factor of autophagy in M. oryzae.

MoAtg14 has only one coiled-coil domain. MoAtg14 interacts with MoAtg6 through this coiled-coil domain, and this interaction is required for autophagy. The coiled-coil domain of MoAtg14 is related to autophagy and pathogenicity. However, the N-terminus or C-terminus of MoAtg14 is not essential for autophagy and pathogenicity. The Barkor/Atg14(L) autophagosome-targeting sequence (BATS) domain exists in the C-terminal half of mammalian Atg14. The BATS domain preferentially binds to the highly curved membranes containing PI3P and is proposed to target the PI3-K complex efficiently to the isolation membrane37,44. In yeast, there are three predicted coiled-coil domains within Atg14p. Recent studies show that the C-terminus controls the size of the autophagosome although there is no conserved domain in yeast Atg1435,39. Therefore, it is interesting to search for the potential functions of every part of MoAtg14 in M. oryzae.

The class III PI3-K complex is the critical regulator of autophagy. In yeast, there are two distinct PI3-K complexes as follows: the type I complex consisting of Vps34, Vps15, Atg6/Vps30 and Atg14, and the type II complex containing Vps34, Vps15, Atg6/Vps30, and Vps38. Atg14 and Vps38 are specifically integrated into type I and type II complexes, respectively. In addition, Atg14 and Vps38 play key roles in determining the function of PI3-K complexes33,45. The two distinct PI3-K complexes have been studied in mammals and found to be similar to those in yeast. The counterparts of Vps34, Vps15, and Vps30/Atg6 are Vps34, p150, and Beclin 1, respectively. The mammalian UV irradiation resistance-associated gene (UVRAG) has been identified as identical to yeast Vps38. Researchers found another PI3-K complex consisting of Vps34, Vps15, Beclin 1, UVARG and Rubicon46,47,48. In M. oryzae, MoAtg14 has been confirmed to play key roles in autophagy, and it interacts with MoAtg6 via the conserved coiled-coil domain. Hence, we deduced that the type I PI3-K complex might be conserved in M. oryzae. Although the conserved functions of MoAtg14 have been confirmed in our studies, it is necessary to solve a problem on the mechanism of MoAtg14 bridges MoAtg6 to form the type I PI3-K complex in M. oryzae. The other protein, MGG_13375 (designated as MoVps38), shows higher similarity to mammalian UVRAG protein (a counterpart of the mammalian Vps38) and has the conserved coiled-coil domain. It implied that MGG_13375 might represent the fungal ortholog of Vps38. In addition, MoVps38 interacted with MoAtg6 using the yeast two hybrid assays (data not show). We speculated that the other distinct PI3-K complex members might exist in M. oryzae. Unfortunately, the null mutant of MoVps38 was not obtained in the wild-type strain Guy11 by screening hundreds of transformants. MoVps38 might play key roles and be a viable factor in M. oryzae. Similar results were shown in Sordaria macrospora. SmVps15 and SmVps34, the homologs of yeast Vps15 and Vps34 in the class III PI3-K complex, were identified in S. macrospora49. However, the authors could not generate the homokaryotic knockout mutant of SmVps15 and SmVps34. This result suggested that Smvps34 and Smvps15 are required for viability. It is necessary to ascertain the components of the type II PI3-K complex or other types of the PI3-K complex.

In conclusion, this study describes the functions of MoAtg14 in M. oryzae, a hitherto uncharacterized protein. Based on the sequence alignment and functional similarity, MoAtg14 is the homolog of yeast Atg14. During the development of M. oryzae, MoAtg14 plays key roles in aerial hyphae, conidiation, degradation of glycogen, numbers of lipid bodies, autophagic cell death and pathogenicity. The autophagy process is blocked in the ΔMoatg14 mutant. Loss of MoAtg14 prevents MoAtg8 from leaving the PAS structures in M. oryzae. MoAtg14 could co-localize with MoAtg8. MoAtg14 directly interacted with MoAtg6 through the coiled-coil domain. Further work is needed to determine the diverse functions beyond autophagy of MoAtg14 in M. oryzae.

Experimental Procedures

Fungal strains and culture conditions

The wild-type strain Guy11 and the mutants of M. oryzae were cultured on complete medium (CM) at 25 °C with a 12-h photophase, as described previously50. Other media included V8 medium, OMA medium and MM as reported previously42. For DNA and RNA extractions, mycelia were harvested from 7-day-old cultures grown in liquid CM at 25 °C with shaking at 150-rpm. General molecular biology techniques for nucleic acid analysis were performed according to standard protocols51. Phenotypic analyses including screens for the formation of conidia, conidiophore formation, conidia germination, appressoria formation, and pathogenicity assays were carried out as reported previously42.

Generation of the knockout vector and mutants

The MoATG14 gene deletion vector was constructed using a strategy based on double-joint PCR52. The 1.0 kb upstream and 1.2 kb downstream flanking sequences of the MoATG14 were amplified from Guy11 genomic DNA using the primers ATG14up-1/2 and ATG14dn-1/2, respectively. A 1.4 kb HPH cassette was cloned from pCB1003 using the primers HPH-1/2. The three amplicons were joined together in the second round of PCR, the product of which served as the template for the final construct amplification using the nested primers ATG14-N-1/2. The double-joint PCR product was inserted into the SalI/XbaI sites of pCAMBIA1300 to generate the targeted-gene-deletion vector (Fig. 2A). The vector was introduced into the wild-type strain Guy11 via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (ATMT) as described previously53. After PCR screening using ATG14-C-1/2, the putative MoAtg14 null mutants were confirmed by Southern blot analysis. For the complementation assay, a 4.0-kb PCR product containing a 2.0-kb upstream sequence, a full-length MoATG14 gene coding region, and a 0.6-kb downstream sequence was amplified from Guy11 genomic DNA using the primers ATG14C-1/2, and inserted into a modified pCAMBIA1300 vector, which contained a geneticin resistance gene. The resulting vector for the complementation assay was randomly inserted into the genome of the ΔMoatg14 mutant using the ATMT method. Southern blot analysis was carried out to verify the single-copy integration according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the Digoxigenin (DIG) High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit I (Roche, USA). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described previously15.

Construction of the pGFP-MoAtg14, pMoAtg14-ΔC, pMoAtg14-ΔN and pMoAtg14-ΔCCD vectors

The cDNA fragment containing the full coding sequence of the MoATG14 gene was cloned from the 24 h-appressoria cDNA library54, and inserted to the XbaI site of the vector pKD5-GFP using the primers Atg14FL-F/R to generate the vector pGFP-MoAtg14. The C-terminal, N-terminal, and coiled-coil domain (CCD) fragments were amplified from the MoATG14 cDNA using the primers Atg14C-F/R, Atg14N-F/R, and Atg14CCD-F/R, respectively. The amplified fragments were inserted into the SmaI/XbaI, XbaI, and SmaI/BamHI sites of the vector pKD6142 to generate the vectors pMoAtg14-ΔC, pMoAtg14-ΔN, and pMoAtg14-ΔCCD, respectively. The vectors were introduced into the mutant ΔMoatg14 via ATMT.

Protein manipulation and immunoblot analysis

Total protein extractions and SDS-PAGE were carried out as reported previously. For the GFP-MoAtg8 proteolysis assay, the pGFP-MoAtg8 vector was transformed into Guy11 and the mutants using the ATMT method as previously described42. Transformants expressing GFP-MoAtg8 were selected to detect full-length GFP-MoAtg8 and free GFP with anti-GFP western blots. The total protein content for the western blots was quantified using a Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Biyuntian, China).

Staining and Microscopy

Conidial suspensions (1 × 105/ml) were incubated on hydrophobic films to form appressoria in a humid chamber at 25 °C. Glycogen and lipid bodies were observed during development at 0 h, 4 h, 8 h and 24 h post-incubation with KI/I2 and Nile red staining as previously described18,40. To detect autophagic cell death, fluorescein diacetate (FDA), a viability stain for cells, was used. The samples were treated with 25 μg/ml FDA staining solution and incubated at room temperature for 4 to 5 minutes in the dark. FDA signals were analyzed with fluorescent microscopy.

Fluorescent microscopy observations were carried out as previously described42. Light and epifluorescence microscopic examinations were performed using an Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon) and a ZEISS LSM780 inverted confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc.).

Yeast two-hybrid interaction

The CDS of MoAtg6 was cloned into pGBKT7 (Clontech, USA) to form the bait constructs. Similarly, MoAtg14 was cloned into pGADT7. The construct strategy used the In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Clontech, USA) and the primer pairs were listed in Table S1. The resulting prey and bait constructs were confirmed by sequencing analysis and co-transformed in pairs into the yeast strain AH109 according to the instructions of the Matchmaker Gal4 Two-Hybrid System 3 (Clontech, USA). The positive transformants on SD-Leu-Trp medium were then tested on SD-Ade-His-Leu-Trp medium. The positive and negative control strains used in the assay were from the cloning kit.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, X.-H. et al. Autophagy-related protein MoAtg14 is involved in differentiation, development and pathogenicity in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Sci. Rep. 7, 40018; doi: 10.1038/srep40018 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants (No. 31371890, 31370171 and 31401687) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Footnotes

Author Contributions X.H., X.Q., and F.C. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all figures and tables; X.Q., Y.H., L.Y., X.M., B., Y., Z.Z., and X.H. conducted the experiments. J.P., F.C., X.H., and X.Q. analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Talbot N. J. On the trail of a cereal killer: Exploring the biology of Magnaporthe grisea. Annu Rev Microbiol. 57, 177–202 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean R. et al. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Molecular plant pathology. 13, 414–430 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. A. & Talbot N. J. Under pressure: investigating the biology of plant infection by Magnaporthe oryzae. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 7, 185–195 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. R. & Hamer J. E. MAP kinase and cAMP signaling regulate infection structure formation and pathogenic growth in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Genes & development 10, 2696–2706 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. R., Staiger C. J. & Hamer J. E. Inactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Mps1 from the rice blast fungus prevents penetration of host cells but allows activation of plant defense responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 12713–12718 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders D. G., Aves S. J. & Talbot N. J. Cell cycle-mediated regulation of plant infection by the rice blast fungus. The Plant cell. 22, 497–507 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Urdiroz M., Oses-Ruiz M., Ryder L. S. & Talbot N. J. Investigating the biology of plant infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Fungal Genet Biol. 90, 61–68 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veneault-Fourrey C., Barooah M., Egan M., Wakley G. & Talbot N. J. Autophagic fungal cell death is necessary for infection by the rice blast fungus. Science. 312, 580–583 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw M. J. & Talbot N. J. Genome-wide functional analysis reveals that infection-associated fungal autophagy is necessary for rice blast disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 15967–15972 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. H. et al. Autophagy vitalizes the pathogenicity of pathogenic fungi. Autophagy 8, 1415–1425 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M. et al. MoGrr1, a novel F-box protein, is involved in conidiogenesis and cell wall integrity and is critical for the full virulence of Magnaporthe oryzae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 99, 8075–8088 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y. et al. Polyubiquitin is required for growth, development and pathogenicity in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. PloS one. 7, e42868 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. et al. Rice RING protein OsBBI1 with E3 ligase activity confers broad-spectrum resistance against Magnaporthe oryzae by modifying the cell wall defence. Cell research. 21, 835–848 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan I. A. et al. Disruption and molecular characterization of calpains-related (MoCAPN1, MoCAPN3 and MoCAPN4) genes in Magnaporthe oryzae. Microbiol Res. 169, 844–854 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. H. et al. Calpains are involved in asexual and sexual development, cell wall integrity and pathogenicity of the rice blast fungus. Sci Rep. 6, 31204 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B. & Klionsky D. J. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Developmental cell. 6, 463–477 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibutani S. T. & Yoshimori T. A current perspective of autophagosome biogenesis. Cell research. 24, 58–68 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. H. et al. Involvement of a Magnaporthe grisea serine/threonine kinase gene, MgATG1, in appressorium turgor and pathogenesis. Eukaryot Cell. 6, 997–1005 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B. et al. MgAtg9 trafficking in Magnaporthe oryzae. Autophagy. 5, 946–953 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. P., Liu X. H., Feng X. X., Min H. & Lin F. C. An autophagy gene, MgATG5, is required for cell differentiation and pathogenesis in Magnaporthe oryzae. Curr Genet. 55, 461–473 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. B. et al. The cysteine protease MoAtg4 interacts with MoAtg8 and is required for differentiation and pathogenesis in Magnaporthe oryzae. Autophagy. 6, 74–85 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y. Z., Ramos-Pamplona M. & Naqvi N. I. Autophagy-assisted glycogen catabolism regulates asexual differentiation in Magnaporthe oryzae. Autophagy. 5, 33–43 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. N. et al. Autophagy-related lipase FgATG15 of Fusarium graminearum is important for lipid turnover and plant infection. Fungal Genet Biol. 48, 217–224 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. FgMon1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor of FgRab7, is important for vacuole fusion, autophagy and plant infection in Fusarium graminearum. Sci Rep. 5, 18101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefsen L. et al. Autophagy provides nutrients for nonassimilating fungal structures and is necessary for plant colonization but not for infection in the necrotrophic plant pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Autophagy. 8, 326–337 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura M. et al. Atg26-mediated pexophagy is required for host invasion by the plant pathogenic fungus Colletotrichum orbiculare. The Plant cell. 21, 1291–1304 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesher I., Barhoom S. & Sharon A. Cell cycle and cell death are not necessary for appressorium formation and plant infection in the fungal plant pathogen Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. BMC biology. 6, 9 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne M., Bailey J. A., Dron M. & Langin T. clk1, a serine/threonine protein kinase-encoding gene, is involved in pathogenicity of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum on common bean. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 11, 99–108 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Vogel G., Lammer F., Kamper J. & Basse C. W. Uniparental mitochondrial DNA inheritance is not affected in Ustilago maydis Deltaatg11 mutants blocked in mitophagy. BMC microbiology. 15, 23 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal M. & Gold S. E. The autophagy genes ATG8 and ATG1 affect morphogenesis and pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. Mol Plant Pathol. 11, 463–478 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Zhao J., Guo W. & Zhang T. Functional analysis of autophagy genes via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in the vascular wilt fungus Verticillium dahliae. J Genet Genomics. 40, 421–431 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. S., Klionsky D. J., Banta L. M. & Emr S. D. Protein sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of mutants defective in the delivery and processing of multiple vacuolar hydrolases. Mol Cell Biol. 8, 4936–4948 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A., Noda T., Ishihara N. & Ohsumi Y. Two distinct Vps34 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes function in autophagy and carboxypeptidase Y sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 152, 519–530 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown W. J., DeWald D. B., Emr S. D., Plutner H. & Balch W. E. Role for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in the sorting and transport of newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 130, 781–796 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara K. & Ohsumi Y. Atg14: a key player in orchestrating autophagy. International J Cell Biol. 2011, 713435 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q. et al. Identification of Barkor as a mammalian autophagy-specific factor for Beclin 1 and class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 19211–19216 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E., Kishi C., Inoue K. & Mizushima N. Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell. 19, 5360–5372 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E. & Mizushima N. Atg14 and UVRAG: mutually exclusive subunits of mammalian Beclin 1-PI3K complexes. Autophagy. 5, 534–536 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara K., Sekito T. & Ohsumi Y. Assortment of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes–Atg14p directs association of complex I to the pre-autophagosomal structure in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 17, 1527–1539 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thines E., Weber R. W. & Talbot N. J. MAP kinase and protein kinase A-dependent mobilization of triacylglycerol and glycogen during appressorium turgor generation by Magnaporthe grisea. The Plant cell. 12, 1703–1718 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong H. & Klionsky D. J. Biochemical methods to monitor autophagy-related processes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 451, 1–26 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. H. et al. The small GTPase MoYpt7 is required for membrane fusion in autophagy and pathogenicity of Magnaporthe oryzae. Environ Microbiol. 17, 4495–4510 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veneault-Fourrey C. & Talbot N. J. Autophagic cell death and its importance for fungal developmental biology and pathogenesis. Autophagy. 3, 126–127 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Nassiri A. & Zhong Q. Autophagosome targeting and membrane curvature sensing by Barkor/Atg14(L). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 7769–7774 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kametaka S., Okano T., Ohsumi M. & Ohsumi Y. Apg14p and Apg6/Vps30p form a protein complex essential for autophagy in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 273, 22284–22291 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y. et al. Distinct regulation of autophagic activity by Atg14L and Rubicon associated with Beclin 1-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase complex. Nat Cell Bio. 11, 468–476 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petiot A., Ogier-Denis E., Blommaart E. F., Meijer A. J. & Codogno P. Distinct classes of phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinases are involved in signaling pathways that control macroautophagy in HT-29 cells. J Biol Chem. 275, 992–998 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q., Westphal W., Wong K. N., Tan I. & Zhong Q. Rubicon controls endosome maturation as a Rab7 effector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 19338–19343 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt O., Herzog B., Jakobshagen A. & Poggeler S. Autophagic kinases SmVPS34 and SmVPS15 are required for viability in the filamentous ascomycete Sordaria macrospora. Microbiol Res. 169, 128–138 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot N. J., Ebbole D. J. & Hamer J. E. Identification and characterization of MPG1, a gene involved in pathogenicity from the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. The Plant cell. 5, 1575–1590 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F. & Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, NY (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. H. et al. Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 41, 973–981 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho H. S., Kang S. & Lee Y. H. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of the plant pathogenic fungus, Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Cells. 12, 407–411 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. P., Liu T. B. & Lin F. C. Identification of mature appressorium-enriched transcripts in Magnaporthe grisea, the rice blast fungus, using suppression subtractive hybridization. FEMS microbiology letters. 245, 131–137 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.