Abstract

Although there was no impairment in IL-2 secretion and proliferation of Fyn-deficient naïve CD4 cells after stimulation with antigen and antigen-presenting cells, stimulation of these cells with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 revealed profound defects. Crosslinking of purified wild-type naïve CD4 cells with anti-CD3 activated Lck and initiated the signaling cascade downstream of Lck, including phosphorylation of ZAP-70, LAT, and PLC-γ1; calcium flux; and dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT)p. All of these signaling events were diminished severely in Fyn-deficient naïve cells activated by CD3 crosslinking. Coaggregation of CD3 and CD4 reconstituted this Lck-dependent signaling pathway in Fyn-/- T cells. These results suggest that when signaling of naïve T cells is restricted to the T cell antigen receptor, Fyn plays an essential role by positive regulation of Lck activity.

Signaling through the T cell antigen receptor (TCR) is initiated by the activity of the Src family tyrosine kinases, Fyn and Lck (1). It has been shown in numerous studies using Lck-deficient cell lines and mice whose peripheral T cells are deficient in Lck that this enzyme plays a critical upstream role in the signaling cascade leading to T cell development, activation, and differentiation (2). In contrast to Lck, the role of Fyn kinase in T cell activation and development is less well defined. With the exception of natural killer T (NKT) cells (3, 4), Fyn deficiency has little or no effect on T cell development in the thymus, and peripheral T cells from Fyn-deficient mice, to the extent they have been studied, show variable and incomplete defects in mounting immune responses (5-7). These findings are consistent with the concept that, for the most part, Fyn is a redundant Src kinase without a unique function in the signaling of T cells. The finding that some of the substrates for Lck [such as the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) of TCRζ as well as CD3γδε] can also serve as substrates for Fyn (8) supports this view. Furthermore, some substrates of ZAP-70, such as Vav (9) and SLP 76 (8), are also substrates of Fyn. However, other studies have shown that Fyn has its own unique substrates, some of which play significant roles in T cell activation. These include ADAP (SLAP-130/FYB) (10), Pyk2 (11), WASp (12), and CBP (13). Other indications that Fyn plays some unique role in TCR-mediated signaling come from our previous studies that have shown that stimulation of T cells with low affinity ligands that function as TCR antagonists leads to preferential activation of Fyn in the absence of any detectable changes in the activity of Lck or ZAP-70 (14, 15). Also, Fyn-deficient T cells are particularly inefficient at responding to weak TCR agonists (7).

Because of these more recent findings that suggest a unique role for Fyn in T cell activation, we have reinvestigated the capacity of Fyn-deficient T cells to respond to TCR-mediated signaling in this study. We compared naïve CD4 T cells from Fyn-deficient and wild-type mice that contained a TCR transgene for their capacity to respond to either antigen presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) or to respond to antibody-mediated CD3 crosslinking. These experiments demonstrated that the relative importance of Fyn depended highly on the mode of stimulation and the activation status of T cells; stimulation of Fyn-deficient T cells by antigen-pulsed APCs led to a robust proliferative and IL-2 response, whereas anti-CD3-mediated stimulation revealed a profound signaling defect in Fyn-deficient T cells. This defect could be corrected by the cocrosslinking of CD3 with CD4. Furthermore, the signaling defect of Fyn-deficient T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 was restricted to naïve T cells and was not observed when Fyn-deficient effector T cells were analyzed. Biochemical experiments on anti-CD3 stimulated cells strongly suggest that the presence of Fyn was necessary for an effective recruitment and/or activation of Lck in the region of the TCR.

Materials and Methods

Animals. Pigeon cytochrome c (PCC)-specific AD10 TCR transgenic (Tg) mice were bred on a B10.A background (16, 17) in our animal facility. B10.A, B6.129 SF2J, and Fyn-/- B6.129 SF2J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Fyn-/- mice were bred onto AD10 TCR Tg genetic background in our animal facility (15).

Antibodies and Reagents. The following antibodies were used in this study: biotinylated anti-mouse CD3ε (2C11), biotinylated anti-mouse CD4 (RM4-5), anti-mouse CD28 (37.51), anti-mouse IL-2 (JES6-1A12), biotinylated anti-mouse IL-2 (JES6-5H4), and recombinant mouse IL-2 (BD Biosciences and Pharmingen); anti-mouse nuclear factor of activated T cells p (NFATp) (4G6-G5), anti-Lck (3A5), and anti-Fyn (FYN3) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-phospho-Y783 PLC-γ1, anti-phospho-Y319 ZAP-70, anti-phospho-Y171 LAT, anti-PLC-γ1, and anti-ZAP-70 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); and anti-LAT (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). Alexa Fluor 633, Alexa Fluor 488, and Indo-1-AM were purchased from Molecular Probes. Streptavidin and ionomycin were purchased from Pierce and Calbiochem, respectively. Enolase purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and rabbit muscle were purchased from Sigma. PCC 88-104 peptide was synthesized on a Symphony synthesizer (Rainin Instruments) and purified as described (18).

Cells. Naïve CD4 cells were purified from lymph nodes and spleens of 8- to 12-week-old mice by using CD4 T cell isolation kits and LS separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Flow cytometry demonstrated that >95% of purified cells were CD4+ CD62Lhigh. For APCs, irradiated (3,000 rad; 1 rad = 0.01 Gy) B10.A spleen cells depleted of T cells by Thy 1.2 MicroBeads and LS separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec) were used. CH27, a mouse B lymphoma cell line that expresses I-Ek, was also used as APCs in some experiments.

Cell Cultures. Cells were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μM 2-ME, nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10% FCS (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA), and antibiotics. To generate effector cells, 1 × 106 naïve CD4 cells from Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- AD10 TCR Tg mice were cultured with 2 × 107 irradiated APCs from B10.A mice in the presence of 1 μg/ml PCC 88-104 peptide for 8 days with the addition of recombinant mouse IL-2 (1 ng/ml) on day 4.

IL-2 Secretion and Proliferation. Purified naïve or effector CD4 cells were plated at 1 × 105 cells per well in 0.2-ml 96-well flat-bottomed tissue culture-untreated plates (Falcon) coated with anti-CD3 with or without the addition of anti-CD4. Soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) was also added to the culture. Alternatively, CD4 cells were plated at 1.0 × 105 cells per well with 5.0 × 105 APCs and PCC 88-104 peptide (1 μg/ml) in 96-well flat-bottomed plates (Falcon). Supernatants were taken between 24 and 48 h of culture to measure IL-2 by ELISA (BD Biosciences and Pharmingen). For proliferation, the uptake of tritiated thymidine [1 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq); ICN] at 48-64 h of culture was determined.

Intracellular Free Calcium. CD4 cells were loaded with Indo-1-AM as described in ref. 19, incubated with biotinylated anti-CD3 with or without biotinylated anti-CD4 at room temperature for 30 min, centrifuged, and resuspended at 1 × 106 cells per ml. Cells were analyzed on a LSR flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed by using flowjo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). To measure intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in CD4 cells stimulated with antigen and APCs, CD4 cells that formed conjugates with APCs were identified as described (20). Briefly, naïve CD4 cells purified from Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- AD10 TCR Tg mice were labeled with Alexa Fluor 633 and loaded with Indo-1-AM. CH27 APCs were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 and pulsed with 10 μg/ml PCC 88-104 peptide. CD4 and CH27 cells were mixed, centrifuged briefly, incubated at 37°C for 2 min, resuspended, and analyzed by flow cytometry. [Ca2+]i analysis was performed on Alexa 633/Alexa 488 double-positive T cell-APC conjugates.

Immunoblotting. NFATp was detected in whole-cell lysates by immunoblotting as described (21). To analyze tyrosine-phosphorylated ZAP-70, LAT, and PLC-γ1, 8 × 106 naïve CD4 cells were incubated with biotinylated anti-CD3 with or without biotinylated anti-CD4 (5 μg/ml each) on ice for 30 min, centrifuged, and resuspended in ice-chilled PBS. After prewarming at 37°C for 1 min, cells were crosslinked by addition of streptavidin (50 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 30 sec. Total-cell lysates were separated by 8% SDS/PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred onto Immobilon-P, and probed with anti-phosphopeptide antibodies and, subsequently, antibodies against ZAP-70, LAT, and PLC-γ1 proteins, as indicated.

In Vitro Kinase Assays. Naive CD4 cells (2 × 107 cells per sample) were preincubated with biotinylated anti-CD3 with or without biotinylated anti-CD4, crosslinked with streptavidin, and solubilized in 1% Nonidet P-40/150 mM NaCl/20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/5 mM EDTA/1% aprotinin/10 μg/ml leupeptin/1 mM Na3VO4/1 mM PMSF. The anti-Fyn and anti-Lck immunoprecipitates were subjected to in vitro kinase assays as described (15) by using enolase from rabbit muscle and S. cerevisiae (Sigma) for Lck and Fyn, respectively.

Nuclear Extraction and Electrophoretic Mobility-Shift Assay. After stimulation, T cells were lysed in 0.2% Nonidet P-40, and nuclei were recovered and salt-extracted as described (22). Nuclear extracts (1-5 μg) were incubated with 3 × 104 cpm of double-stranded oligonucleotide probes. The probes specific for activator protein 1 (AP-1) (5′-CGCTTGATGAGTCAGCCGGAA-3′) and NF-κB (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) were purchased from Promega and end-labeled with γ-[32P]ATP. After 20 min of incubation, complexes were separated on 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels.

Results

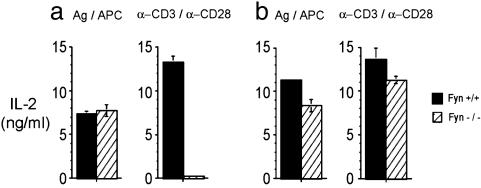

Effect of Fyn Deficiency on TCR-Mediated Activation of Naïve CD4 Cells. To determine the role of Fyn in the activation of naïve CD4 cells, we used wild-type or Fyn-deficient mice that expressed a transgene for a TCR specific for PCC 88-104 peptide presented by the class II MHC, I-EK. Purified CD4 T cells from these mice were stimulated in two different ways, either (i) by the cognate epitope PCC 88-104 pulsed onto APCs, or (ii) to confine stimulation to a simpler system involving TCR-mediated stimulation, with plate-bound anti-CD3 antibodies and soluble anti-CD28. T cell activation was measured by the production of IL-2. Strikingly, different results were obtained with respect to the ability of Fyn-/- T cells to respond to these two modes of stimulation. As shown in Fig. 1a, Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T cells responded equivalently when stimulated by antigen-pulsed APCs. In contrast, the same Fyn-deficient T cells, when stimulated by anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, demonstrated a severe defect in IL-2 production. Low to undetectable quantities of IL-2 were observed routinely in the cultures containing Fyn-/- T cells, whereas vigorous IL-2 responses were obtained in the Fyn+/+ T cell cultures. A similar, albeit less striking, defect in proliferation of anti-CD3 stimulated Fyn-/- T cells was also observed (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 1.

Fyn is required for naïve CD4 cells to respond to anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation. (a) Naïve CD4 cells purified from AD10 TCR Tg mice on Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- backgrounds were stimulated either with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 or antigen (PCC 88-104) and irradiated APCs. (b) Effector CD4 cells generated in vitro were stimulated either with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 or antigen (PCC 88-104) and irradiated APCs.

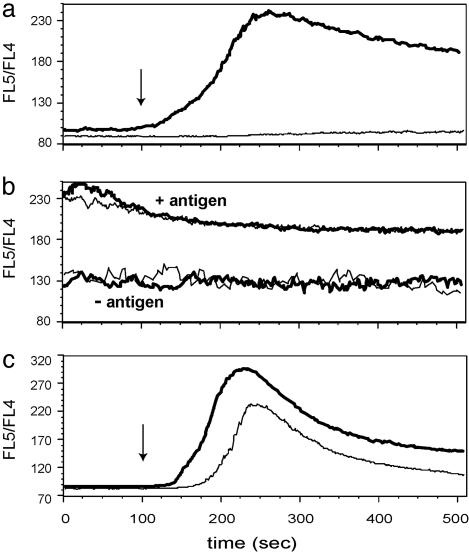

Failure of Fyn-/- T Cells to Increase Cytosolic Ca2+ After TCR Crosslinking. The striking contrast between the ability of naïve Fyn-deficient T cells to produce IL-2 after stimulation with antigen-pulsed APCs and their inability to respond to anti-CD3-coated plates in the presence of soluble anti-CD28 suggested that, in the absence of T cell-APC conjugates with the consequent translocation of various costimulatory, adhesion, and signaling molecules in close proximity to the TCR, Fyn plays a critical nonredundant role in TCR-mediated stimulation. To assess the signaling defect in Fyn-/- T cells, we examined the intracellular calcium after TCR crosslinking. The data shown in Fig. 2a substantiate the inability of Fyn-/- T cells to respond normally to TCR crosslinking. Whereas Fyn+/+ T cells gave a vigorous calcium response after CD3 crosslinking, Fyn-deficient cells showed no detectable increase in intracellular calcium. As a control, the calcium response to the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin was measured and shown to be normal (data not shown). The calcium response of Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- cells was examined also after their stimulation by antigen-pulsed APCs. Because of the necessity of centrifuging the T cells and APCs together to promote the formation of conjugates, it was not possible to study the initial rise in intracellular Ca2+, but the subsequent plateau phase of the response was analyzed readily, and as shown in Fig. 2b, Fyn+/+, and Fyn-/- T cells responded similarly to this mode of stimulation. Thus, as was observed for IL-2 secretion, a striking difference in the capacity of Fyn-deficient cells to respond to antibody-mediated TCR crosslinking and antigen plus APC stimulation was also evident when Ca2+ responses were studied.

Fig. 2.

Fyn is required for calcium response after crosslinking of CD3 on naïve CD4 cells. (a) Naïve CD4 cells from Fyn+/+ (thick line) and Fyn-/- (thin line) AD10 TCR Tg mice were loaded with Indo-1-AM, preincubated with biotinylated anti-CD3, and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD3 was crosslinked with streptavidin at 100 sec of the analysis (arrow). (b)Naïve CD4 cells from Fyn+/+ (bold line) and Fyn-/- (thin line) AD10 TCR Tg mice were labeled with Alexa 633 and loaded with Indo-1-AM. CH27 cells were labeled with Alexa 488 and pulsed with 0 or 10 μg/ml PCC 88-104 peptide. CD4 cells and CH27 cells were mixed, centrifuged, incubated at 37°C for 2 min, and applied to a flow cytometer. The calcium levels of CD4 cells that formed conjugates with CD27 cells, identified as Alexa 633/Alexa 488 double-positive population, were analyzed. (c) Fyn+/+ (thick line) and Fyn-/- (thin line) effector CD4 cells were loaded with Indo-1-AM, preincubated with biotinylated anti-CD3, and crosslinked with streptavidin at 100 sec (arrow).

Effector T Cells from Fyn-Deficient Mice Respond Normally to TCR Crosslinking. The response of previously primed effector or memory T cells differs in several respects from naïve T cells, including an increased antigen sensitivity (16) and a decreased dependency on costimulation (23). Because of these differences, we wanted to determine whether the defect in IL-2 production and the lack of a calcium response that was observed after CD3 crosslinking of naïve Fyn-/- T cells would be seen also with previously primed effector T cells. As shown in Fig. 1b, effector Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T cells secreted similar amounts of IL-2 when stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. Similarly, the calcium response to CD3 crosslinking of previously primed Fyn-/- T cells was almost as vigorous as wild-type effector T cells (Fig. 2c).

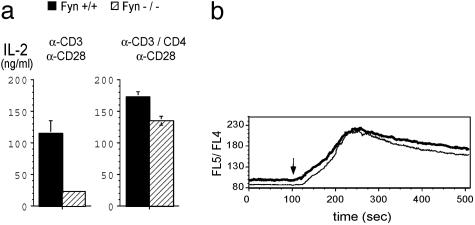

Naïve Fyn-/- T Cells Respond Normally When Stimulated by Cocrosslinking of CD3 and CD4. The data presented above indicated that when stimulation of naïve CD4 T cells was restricted to engagement of the TCR without costimulatory T cell molecules involved in the signaling (other than CD28), Fyn played a critical role in the initial phase of activation. Because Fyn has been shown to be constitutively associated with the TCR (24), we postulated that a critical difference between anti-CD3-mediated stimulation and antigen/APC-mediated stimulation might be the absence of a Src kinase in close proximity of the TCR when Fyn-/- T cells were stimulated by anti-CD3. To test this idea, we examined the effect of CD3 and CD4 cocrosslinking on the calcium response and IL-2 production. Under these conditions, CD4-associated Lck would be brought into proximity of the TCR. It was found that cocrosslinking CD3 and CD4 almost completely corrected the defect in IL-2 production of Fyn-/- naïve T cells (Fig. 3a Right) and the calcium response was indistinguishable from that of wild-type CD4 T cells (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Cocrosslinking of CD3 and CD4 overcomes the signaling defect in Fyn-/- T cells. (a)Naïve CD4 cells purified from Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- B6.129 SF2J mice were cultured in plates coated with anti-CD3 or anti-CD3 and anti-CD4 in the presence of soluble anti-CD28. (b)Naïve CD4 cells from Fyn+/+ (thick line) and Fyn-/- (thin line) mice were loaded with Indo-1-AM, preincubated with biotinylated anti-CD3 and biotinylated anti-CD4, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were crosslinked with streptavidin at 100 sec of the analysis (arrow).

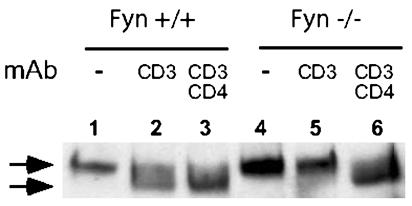

Dephosphorylation and Nuclear Localization of NFATp (NFATc2, NFAT1) in Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T Cells. One of the most important consequences of the rise in intracellular calcium after TCR-mediated signaling is the activation of calcineurin and dephosphorylation and nuclear transport of NFAT. To determine whether the failure of anti-CD3 crosslinking to induce a discernible calcium response in Fyn-/- T cells was associated with a defect in NFAT dephosphorylation, Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T cells were stimulated by CD3 crosslinking, and the NFATp in whole-cell lysates was analyzed by immunoblotting. The data shown in Fig. 4 are consistent with the calcium data, and they indicate that NFATp dephosphorylation occurred in Fyn+/+ cells after anti-CD3 crosslinking but not in Fyn-/- T cells (compare lanes 2 and 5). In contrast, when Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T cells were incubated with biotinylated anti-CD3 and anti-CD4 and cocrosslinked with streptavidin, NFATp was dephosphorylated efficiently and equivalently in both Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T cells (lanes 3 and 6). As a further analysis of the defect in T cell signaling after anti-CD3 crosslinking in Fyn-/- cells, transport of NFATp into the nucleus after stimulation of Fyn-/- and Fyn+/+ cells was determined. Consistent with the data obtained on NFATp dephosphorylation, Fyn-/- T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 and CD28 failed to transport NFATp into the nucleus (see Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 4.

NFATp dephosphorylation induced by CD3 crosslinking is impaired in Fyn-/- naïve CD4 cells. Naïve CD4 cells were purified from Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- B6.129 SF2J mice. The cells were preincubated with biotinylated anti-CD3 alone or together with biotinylated anti-CD4 and crosslinked with streptavidin at room temperature for 3 min. Total-cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-NFATp mAb. The arrows correspond to phosphorylated (Upper) and dephosphorylated (Lower) NFATp.

Other calcium-regulated transcription factors, such as NF-κB and AP-1, are also involved in IL-2 gene transcription. Electrophoretic mobility-shift assay was performed on nuclear extracts of anti-CD3/CD28 or antigen/APC-stimulated naïve CD4 T cells from Fyn-/- and Fyn+/+ TCR Tg T cells. In agreement with the data obtained on NFATp nuclear localization, both NF-κB and AP-1 were found in greatly reduced quantities in the nuclei of Fyn-/- T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 compared with Fyn+/+ cells. In contrast, Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T cells had similar amounts of nuclear NF-κB and AP-1 after stimulation with antigen-pulsed APCs (see Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

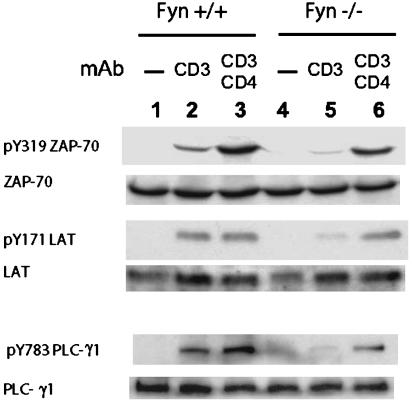

Early Tyrosine Phosphorylation Events in Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T Cells After TCR Crosslinking. Upstream of the increase in intracellular calcium, several important tyrosine phosphorylation events take place. The ITAMs of CD3 and TCRζ chains are phosphorylated by Lck and Fyn, and ZAP-70 is phosphorylated by Lck; subsequently, ZAP-70 phosphorylates other substrates, including LAT, which then binds several SH2-containing molecules, including PLC-γ1, the activity of which at the plasma membrane is critical for a calcium response. To determine whether any of these upstream tyrosine phosphorylation events might be defective in Fyn-/- T cells, Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T cells were stimulated by anti-CD3 or anti-CD3 and anti-CD4 and the total-cell lysate was subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-phosphopeptide antibodies specific for the active forms of ZAP-70, LAT, and PLC-γ1. Fig. 5 shows the results. When Fyn+/+ cells were stimulated by anti-CD3 crosslinking, active forms of ZAP70, LAT, and PLC-γ1 were clearly formed (Fig. 5, lane 2). After CD3 and CD4 cocrosslinking, the amount of phospho-ZAP-70 greatly increased over the level attained by anti-CD3 alone, whereas phospho-LAT and PLC-γ1 showed no (LAT) or only modest (PLC-γ1) further increases (Fig. 5, lane 3). In contrast, anti-CD3 stimulation of Fyn-/- T cells resulted in much less phosphorylation of ZAP-70, LAT, and PLC-γ1. Densitometry of the anti-phosphopeptide immunoblots indicated that anti-CD3 stimulated Fyn+/+ cells (Fig. 5, lane 2) contained 6-fold more phospho-ZAP-70, phospho-LAT, and phospho-PLC-γ1 than Fyn-/- cells (Fig. 5, lane 5). However, cocrosslinking of CD3 with CD4 to a large extent corrected the signaling deficiency of Fyn-/- T cells (Fig. 5, lane 6).

Fig. 5.

Fyn deficiency results in decreased tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70, LAT, and PLC-γ1 induced by crosslinking of CD3. Naïve CD4 cells purified from Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- B6.129 SF2J mice were preincubated with biotinylated anti-CD3 alone (lanes 2 and 5) or together with biotinylated anti-CD4 (lanes 3 and 6) and crosslinked with streptavidin at 37°C for 30 sec. Total-cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-phosphopeptide antibodies specific for pY319 ZAP-70, pY171 LAT, and pY783 PLC-γ1. After stripping, the membranes were probed with anti-protein antibodies specific for ZAP-70, LAT, and PLC-γ1.

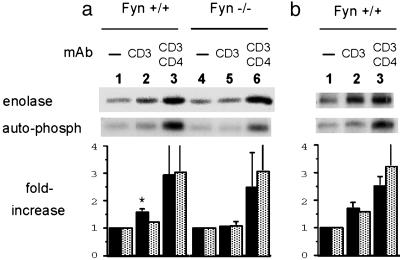

The data obtained with phospho-ZAP-70 indicated that Lck-mediated phosphorylation and activation of ZAP-70 was defective in Fyn-/- cells. This observation could be due to a decrease in cellular Lck enzymatic activity and/or inefficient localization of Lck to the region occupied by TCR and ZAP-70. To examine the functional capacity of Lck directly, Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 or anti-CD3 and CD4 and Lck or Fyn immunoprecipitates were subjected to in vitro kinase assays. Fig. 6 shows both the autophosphorylation and the phosphorylation of an exogenous substrate, enolase. As expected, unstimulated wild-type and Fyn-/- T cells showed considerable constitutive Lck activity, which was modestly increased after CD3 crosslinking in the case of Fyn+/+ T cells (Fig. 6a, lane 2). In contrast, Fyn-/- T cells stimulated by anti-CD3 crosslinking showed no increase in Lck activity, as measured by autophosphorylation or enolase phosphorylation (Fig. 6a, lane 5). The bar graph in the lower part of Fig. 6a shows the average fold increase from three experiments. Enolase phosphorylation by Lck increased 57% in Fyn+/+ cells after CD3 crosslinking, and autophosphorylation increased by 20%. In Fyn-/- T cells, CD3 crosslinking resulted in only a 6% increase in both Lck autophosphorylation and enolase phosphorylation. Cocrosslinking of CD3 and CD4 led to a substantial increase in Lck activity in both Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- T cells (Fig. 6a, lanes 3 and 6), with an average increase in activity of 2.5- to 3-fold, as determined by autophosphorylation and enolase phosphorylation. Fyn activity after CD3 or CD3 plus CD4 crosslinking of wild-type T cells was analyzed also (Fig. 6b). After CD3 crosslinking, enolase phosphorylation increased by 70% and autophosphorylation increased by 56%. After CD3/CD4 cocrosslinking, Fyn activity was further increased, with enolase phosphorylation being increased by 2.5-fold and autophosphorylation being increased by 3.2-fold.

Fig. 6.

Regulation by Fyn of Lck activation induced by CD3 crosslinking. Naïve CD4 cells from Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- AD10 TCR Tg mice were preincubated with biotinylated anti-CD3 with or without the addition of biotinylated anti-CD4. Crosslinking was accomplished by the addition of streptavidin at 37°C for 30 sec. Anti-Lck (a) or Fyn (b) immunoprecipitates were subjected to in vitro kinase assays and analyzed by SDS/PAGE for autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of the exogenous substrate enolase. The graphs under the autoradiographs summarize the results of three independent experiments. Enolase phosphorylation (filled bars) and autophosphorylation (dotted bars) were normalized to the unstimulated controls. *, P = 0.03, between Fyn+/+ and Fyn-/- cells.

Discussion

This study was carried out with the goal of determining whether Fyn tyrosine kinase had a unique role in the signaling of CD4 T cells through TCR/CD3. Our results demonstrate that the capacity for Fyn-deficient T cells to be activated depends critically on the mode of stimulation and the prior experience of the T cells. Naïve Fyn-/- CD4 T cells stimulated by CD3 crosslinking had profound defects in the early signaling events of tyrosine phosphorylation and calcium response, which resulted in a markedly reduced ability to produce IL-2 and proliferate. In contrast, previously activated Fyn-/- T cells showed no such activation defects. Furthermore, when naïve Fyn-/- T cells were stimulated by antigen-pulsed APCs or cocrosslinking of CD3 and CD4, no defects in naïve Fyn-/- T cell responses were observed.

Previous characterizations have led to somewhat varied conclusions with regard to the capacity of Fyn-/- peripheral T cells to respond to stimulation. Appleby et al. (6) characterized the proliferative responses of Fyn-/- T cells to anti-CD3 plus PMA, allogeneic spleen cells, and superantigen. In all cases, Fyn-/- T cells responded somewhat less vigorously (15-70%) than wild-type T cells. Stein et al. (5) found a modest decrease in proliferation and a more profound decrease in IL-2 production in response to anti-CD3 and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) stimulation, whereas allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction (allo-MLR) and superantigen proliferative responses were similar to those of Fyn+/+ T cells. Utting et al. (7) found no defect in the proliferative response of Fyn-/- CD8 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3. However, these authors added IL-2 to the cultures, making the results difficult to interpret. Our data are most consistent with those of Stein et al. (5) because their results with APC-mediated responses (MLR and superantigen) showed no defect in Fyn-/- T cells, whereas anti-CD3 stimulation showed a modest defect in proliferation and a profound defect in IL-2 production. The initial reports of the immune function of Fyn-/- mice included a study of the calcium response of spleen cells to anti-CD3 stimulation. Appleby et al. (6) showed a 60-70% reduction only when suboptimal concentrations of anti-CD3 was used to stimulate splenocytes but little or no reduction when optimal amounts of anti-CD3 were used. Stein et al. (5) also reported a partial reduction in the calcium response. The less dramatic defect in the calcium response found by these previous studies, compared with our findings, is most likely explained by our use of purified CD4 cells and the combination of biotinylated anti-CD3 and streptavidin to stimulate them. In the two initial reports on Fyn-/- mice, whole spleen cell populations were used and CD3 crosslinking was accomplished by Fc receptor-bearing cells in the preparations that contained accessory molecules (such as MHC, ICAM, and B7) that could help to stimulate a calcium response.

The major pathway for stimulating a calcium response in T cells after TCR crosslinking involves the tyrosine phosphorylation of the ITAMs on CD3ζ chain by Lck and Fyn, the binding of ZAP-70 to the ITAMs, the phosphorylation and activation of ZAP-70 by Lck, and the phosphorylation by ZAP-70 of the adaptor protein LAT. Phosphorylated LAT serves as a scaffold to bring several molecules to the plasma membrane, including PLC-γ1, the enzyme responsible for cleavage of phosphatidylinositol and the generation of IP3. Because this pathway is strongly Lck-dependent, we investigated the possible role of Fyn in the function of Lck in naïve T cells stimulated by CD3 crosslinking. Surprisingly, we found a profound Fyn dependency on this Lck-dependent signaling pathway. First, activation of ZAP-70, LAT, and PLC-γ were all ≈6-fold lower in Fyn-/- T cells than in Fyn+/+ T cells; second, in vitro kinase assays of Lck after anti-CD3 stimulation of naïve T cells revealed no increase in Lck activity in Fyn-/- T cells, whereas a significant, albeit modest, increase was seen in Fyn+/+ T cells.

A role of Fyn in Lck function is consistent with two other published reports. First, Bothwell and coworkers (25) showed that decreasing Fyn kinase expression in a T cell line by transfection with antisense RNA resulted paradoxically in a decrease in Lck kinase activity as well. Second, Tang et al. (26), by using a similar system to that which we have used, demonstrated that Fyn-/- T cells stimulated by anti-CD3 crosslinking had a reduction in LAT phosphorylation compared with anti-CD3 stimulated wild-type T cells. Conversely, Julius and colleagues (27) showed by using Lck-deficient T cells that Fyn activity could be positively regulated by Lck. Although our data suggest the regulation of Lck by Fyn (Fig. 6a), they are also consistent with the regulation of Fyn by Lck because cocrosslinking of CD3 and CD4 approximately doubled Fyn kinase activity as compared with crosslinking of CD3 alone (Fig. 6b). Our observations, together with the previous reports, suggest that in naïve CD4 T cells, Lck and Fyn have a synergistic effect on one another that leads to increased activity of both enzymes after stimulation through the TCR.

We do not know the mechanism by which Fyn influences Lck function in naïve T cells. It is possible that Fyn can phosphorylate Lck directly and modify its activity, or, by adding to the phosphorylation of the TCR associated ITAMs, increase the concentration of the Lck substrate ZAP-70. However, we favor the possibility that Fyn, by some unknown mechanism, induces the redistribution of Lck to the region where TCR, CD3, and ZAP-70 are localized, thereby facilitating the phosphorylation of CD3 and ZAP-70 by Lck. It is possible that this redistribution of Lck may involve its localization to lipid rafts. Although considerable Lck is detected in lipid rafts in naïve T cells (28), this Lck moiety has been shown to have very little kinase activity (13, 27), and it may be necessary to have enzymatically active Lck transported into lipid rafts to allow effective signaling to occur after CD3 crosslinking. In this regard, it is also of interest that effector cells express markedly enhanced levels of lipid rafts and Lck associated with plasma membrane as compared with naïve T cells (28). This finding would be consistent with our observation that effector cell activation by CD3 crosslinking is Fyn-independent. The observation that cocrosslinking of CD3 and CD4 corrects the signaling deficiency of naïve Fyn-/- T cells is also in keeping with the hypothesis that one role of Fyn is to facilitate the translocation of Lck into proximity of the TCR and that, by forcing the apposition of CD4-associated Lck to the TCR by cocrosslinking CD3 and CD4, the signaling defect in Fyn-/- cells is overcome.

What might be the physiologic significance of Fyn-dependent stimulation of naïve T cells through the TCR? There is compelling evidence that TCR-peptide plus MHC interaction occurs between naïve T cells and APCs in the absence of cognate antigen stimulation and that this interaction is critical for the survival and homeostatic proliferation of T cells (29, 30). In vitro studies have shown that antigen-independent interactions between naïve T cells and dendritic cells result in sufficient T cell signals being generated for a low level Ca2+ response to be detected (31). This response depends on TCR aggregation at the dendritic cell-T cell interface. These data, together with our previous studies that indicate Fyn activation preferentially occurs after stimulation with low-affinity ligands (14, 15), suggest the possibility that TCR interactions with low-affinity self ligands on dendritic cells provide a sufficient stimulus for signaling a Fyn-dependent pathway that is involved in the survival and homeostatic proliferation of naïve T cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Toshi and Yuko Kawakami, Jianyong Huang, and Keith Bahjat (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology) for helpful advice; Jessica Goss, Edmund Ie, Yasuko Kawabara, and Samuel Connell for technical assistance; and Nancy Martorana for assistance in preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (to H.M.G.). This is publication no. 652 from the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology.

Author contributions: K.S. and H.M.G. designed research; K.S. and M.-S.J. performed research; K.S., M.-S.J., and H.M.G. analyzed data; and K.S. and H.M.G. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: PCC, pigeon cytochrome c; Tg, transgenic; TCR, T cell antigen receptor; APC, antigen-presenting cell; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; AP-1, activator protein 1; ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif.

References

- 1.Weiss, A. & Littman, D. R. (1994) Cell 76, 263-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molina, T. J., Kishihara, K., Siderovski, D. P., van Ewijk, W., Narendran, A., Timms, E., Wakeham, A., Paige, C. J., Hartmann, K. U., Veillette, A., et al. (1992) Nature 357, 161-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eberl, G., Lowin-Kropf, B. & MacDonald, H. R. (1999) J. Immunol. 163, 4091-4094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gadue, P., Morton, N. & Stein, P. L. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 190, 1189-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein, P. L., Lee, H. M., Rich, S. & Soriano, P. (1992) Cell 70, 741-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appleby, M. W., Gross, J. A., Cooke, M. P., Levin, S. D., Qian, X. & Perlmutter, R. M. (1992) Cell 70, 751-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Utting, O., Teh, S. J. & Teh, H. S. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 5410-5419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denny, M. F., Patai, B. & Straus, D. B. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1426-1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michel, F., Grimaud, L., Tuosto, L. & Acuto, O. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31932-31938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raab, M., Kang, H., da Silva, A., Zhu, X. & Rudd, C. E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21170-21179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian, D., Lev, S., van Oers, N. S., Dikic, I., Schlessinger, J. & Weiss, A. (1997) J. Exp. Med. 185, 1253-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badour, K., Zhang, J., Shi, F., Leng, Y., Collins, M. & Siminovitch, K. A. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 199, 99-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasuda, K., Nagafuku, M., Shima, T., Okada, M., Yagi, T., Yamada, T., Minaki, Y., Kato, A., Tani-Ichi, S., Hamaoka, T. & Kosugi, A. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 2813-2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, J., Sugie, K., La Face, D. M., Altman, A. & Grey, H. M. (2000) Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 50-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, J., Tilly, D., Altman, A., Sugie, K. & Grey, H. M. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 10923-10929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimachi, K., Croft, M. & Grey, H. M. (1997) Eur. J. Immunol. 27, 3310-3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaye, J., Vasquez, N. J. & Hedrick, S. M. (1992) J. Immunol. 148, 3342-3353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.La Face, D. M., Couture, C., Anderson, K., Shih, G., Alexander, J., Sette, A., Mustelin, T., Altman, A. & Grey, H. M. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 2057-2064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabinovitch, P. S., June, C. H., Grossmann, A. & Ledbetter, J. A. (1986) J. Immunol. 137, 952-961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grebe, K. M. & Potter, T. A. (2002) Sci. STKE 2002, PL14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loh, C., Carew, J. A., Kim, J., Hogan, P. G. & Rao, A. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 3945-3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolmetsch, R. E., Lewis, R. S., Goodnow, C. C. & Healy, J. I. (1997) Nature 386, 855-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croft, M., Bradley, L. M. & Swain, S. L. (1994) J. Immunol. 152, 2675-2685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samelson, L. E., Phillips, A. F., Luong, E. T. & Klausner, R. D. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 4358-4362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, S. K., Shaw, A., Maher, S. E. & Bothwell, A. L. (1994) Int. Immunol. 6, 1621-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang, Q., Subudhi, S. K., Henriksen, K. J., Long, C. G., Vives, F. & Bluestone, J. A. (2002) J. Immunol. 168, 4480-4487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filipp, D., Zhang, J., Leung, B. L., Shaw, A., Levin, S. D., Veillette, A. & Julius, M. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 197, 1221-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuosto, L., Parolini, I., Schroder, S., Sargiacomo, M., Lanzavecchia, A. & Viola, A. (2001) Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 345-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge, Q., Palliser, D., Eisen, H. N. & Chen, J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2983-2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Min, B., Foucras, G., Meier-Schellersheim, M. & Paul, W. E. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 3874-3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delon, J., Bercovici, N., Raposo, G., Liblau, R. & Trautmann, A. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 188, 1473-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.