Abstract

Objective

Increased fructose consumption is a contributor to the burgeoning epidemic of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Recent evidence indicates that the metabolic hormone FGF21 is regulated by fructose consumption in humans and rodents and may play a functional role in this nutritional context. Here, we sought to define the mechanism by which fructose ingestion regulates FGF21 and determine whether FGF21 contributes to an adaptive metabolic response to fructose consumption.

Methods

We tested the role of the transcription factor carbohydrate responsive-element binding protein (ChREBP) in fructose-mediated regulation of FGF21 using ChREBP knockout mice. Using FGF21 knockout mice, we investigated whether FGF21 has a metabolic function in the context of fructose consumption. Additionally, we tested whether a ChREBP-FGF21 interaction is likely conserved in human subjects.

Results

Hepatic expression of ChREBP-β and Fgf21 acutely increased 2-fold and 3-fold, respectively, following fructose gavage, and this was accompanied by increased circulating FGF21. The acute increase in circulating FGF21 following fructose gavage was absent in ChREBP knockout mice. Induction of ChREBP-β and its glycolytic, fructolytic, and lipogenic gene targets were attenuated in FGF21 knockout mice fed high-fructose diets, and this was accompanied by a 50% reduction in de novo lipogenesis a, 30% reduction VLDL secretion, and a 25% reduction in liver fat compared to fructose-fed controls. In human subjects, serum FGF21 correlates with de novo lipogenic rates measured by stable isotopic tracers (R = 0.55, P = 0.04) consistent with conservation of a ChREBP-FGF21 interaction. After 8 weeks of high-fructose diet, livers from FGF21 knockout mice demonstrate atrophy and fibrosis accompanied by molecular markers of inflammation and stellate cell activation; whereas, this did not occur in controls.

Conclusions

In summary, ChREBP and FGF21 constitute a signaling axis likely conserved in humans that mediates an essential adaptive response to fructose ingestion that may participate in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and liver fibrosis.

Keywords: FGF21, ChREBP, Fructose, Lipogenesis, NAFLD

Highlights

-

•

ChREBP is required for fructose-induced increases in circulating FGF21.

-

•

Fructose-induced FGF21 feeds back on the liver to enhance ChREBP activity, lipogenesis, VLDL secretion, and fatty liver.

-

•

Circulating FGF21 correlates with rates of de novo lipogenesis in human subjects.

-

•

In the setting of high-fructose feeding, FGF21 protects the liver against inflammation and fibrosis.

1. Introduction

Increased sugar consumption is a contributor to the worldwide epidemic of obesity and its associated complications [1]. The increasing prevalence of obesity is paralleled by a less obvious epidemic, that of NAFLD [2]. While hepatic steatosis, the first stage in NAFLD, is considered relatively benign with respect to liver disease per se, it may progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and may progress further to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. Sugar consumption, particularly in the form of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), is associated with the development and progression of NAFLD independently of other features of obesity and the metabolic syndrome [3], [4].

Sugar is typically consumed by humans in the form of sucrose or high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), both of which consist of nearly equal amounts of the simple sugars, glucose and fructose. The fructose component of sugar appears to be particularly harmful as excessive consumption of fructose, but not glucose, increases visceral adiposity, serum triglycerides, and insulin resistance [5]. Fructose consumption also stimulates DNL more than glucose [5], [6], [7], which contributes to the development of steatosis and NAFLD [8], [9]. The differential effects of glucose and fructose on NAFLD and other features of metabolic syndrome are, in part, due to the fact that fructose is preferentially metabolized in the liver (reviewed in [10], [11]). We have recently demonstrated that fructose, but not glucose, ingestion acutely and robustly activates hepatic Carbohydrate Responsive-Element Binding Protein (ChREBP) a key carbohydrate sensing transcription factor that regulates glycolytic, fructolytic, and lipogenic gene expression programs [12]. ChREBP KO mice are intolerant to fructose and have reduced hepatic triglyceride levels and hepatic DNL rates on high-starch diets [13]. Thus, fructose may contribute to hepatic steatosis through at least two mechanisms: 1) by providing substrate for fatty-acid synthesis and esterification in the liver and 2) by stimulating hepatic lipogenic gene programs under the control of ChREBP and other signaling factors [reviewed in [14]].

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is a metabolic hormone synthesized by multiple tissues and released into circulation largely by the liver [15], [16], [17]. Pharmacological administration has multiple beneficial metabolic effects [18]. FGF21 was initially identified as a liver hormone regulated by fasting and ketogenic diets under the transcriptional control of PPAR-alpha, a master regulator of fatty acid oxidation [15], [16], [19], [20]. The liver enriched transcription factor CREBH interacts with PPAR-alpha and also participates in regulating FGF21 expression after fasting or high-fat, low-carbohydrate feeding [21], [22]. In mice, FGF21 participates in an adaptive response to fasting or ketogenic diets by enhancing hepatic fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis [15], [20]. In humans, however, neither short term fasting nor consumption of ketogenic diets markedly alter circulating FGF21 levels. In contrast, in humans, fructose ingestion leads to a robust and rapid increase in circulating levels of FGF21, which return to baseline after several hours. Thus FGF21's function in humans may be unrelated to fasting physiology [23], [24], [25].

Interestingly, in mice, high sucrose diets also increase FGF21 [26], [27]. The sugar-sensitive transcription factor ChREBP can transactivate expression of hepatic Fgf21 in vitro and in animal models [27], leading to the hypothesis that sucrose- or fructose-mediated activation of hepatic ChREBP may regulate circulating FGF21, which, in turn, might participate in an adaptive metabolic response to sugar ingestion. An adaptive role for FGF21 in sugar consumption is supported by human population genetics data indicating that variants in the human FGF21 locus regulate carbohydrate consumption [28], [29] as well as recent genetic and pharmacological interventions in rodents and primates indicating that FGF21 regulates sweet taste preferences [30], [31].

Here, we show that the acute FGF21 response to fructose ingestion observed in humans is conserved in mice. Furthermore, using ChREBP KO mice and FGF21 KO mice, we demonstrate that ChREBP is essential for fructose-induced increases in circulating FGF21. Moreover, we show that FGF21 is required for a normal hepatic metabolic response to fructose consumption and that the absence of FGF21 leads to liver disease in mice on high-fructose diets. Lastly, we show that circulating FGF21 in humans correlates with rates of DNL indicating that a sugar-ChREBP-FGF21 signaling axis may play a role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD in humans.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

All studies were carried out using female mice obtained from and maintained at 24 °C on a 12:12-h light–dark cycle. ChREBP KO mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Stock No: 010537; Bar Harbor, ME) and back crossed more than 10 generations onto the C3H/HeJ background. FGF21-KO mice were generated as previously described [15] and back crossed more than 10 generations onto the C57BL/6J background. Mice were fed a chow diet (LabDiet 5008, Pharmaserv, Framingham, MA), a 60% fructose diet, or a 60% dextrose diet (TD.89247 and TD.05256 Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) for indicated durations. Mice were euthanized between 9:00 and 11:30 am under isoflurane anesthesia. All studies were approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical center IACUC.

2.2. Measurements in human subjects

Fourteen of fifteen healthy lean and overweight adult volunteers who participated in a previously published study [7] had given consent for the use of their stored plasma samples for future research. The measurement of levels of FGF21 in these samples was approved by The Rockefeller University Institutional Review Board. The subject characteristics are listed in Supplementary Table 1. DNL was measured as previously described [7].

2.3. RNA isolation and real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA from mouse livers was isolated by TRIzol extraction and purified using Zymo Research Direct-Zol™ mini columns (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed via standard methods using the Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Relative expression of mRNAs was determined after normalization to TATA box binding protein (TBP) and transformed using the equation 2−ΔΔCT.

2.4. In vivo rate of hepatic lipogenesis

DNL was measured as previously described [32]. Briefly, conscious, ad libitum fed mice were injected intraperitoneally with 5 mCi of 3H2O and euthanized 1 h later. Once sacrificed, the liver was frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C for processing. Lipids were extracted by the Folch method. Fatty acids were isolated by saponification and petroleum ether extraction. Incorporation of 3H into fatty acids was measured. The rate of synthesis was calculated as a molar rate estimating 13.3 mol of H2O per newly synthesized C16 fatty acid.

2.5. In vivo VLDL secretion

After a 4 h fast, mice were injected via the tail vain with tyloxapol (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a dose of 500 mg/kg body weight. Serum was collected from tail bleeds at 0, 30, 60 and 120 min. Triglyceride levels were determined using a colormetric assay (StanBio, Boerne, TX).

2.6. Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry

A portion of the median hepatic lobe from each mouse was removed and fixed in 10% formalin at 4 °C overnight. Paraffin embedding and sectioning was performed by the Histology Core at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. 5 μM sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Sirius Red to visualize fibrosis.

2.7. Serum hormones and metabolites

Serum was stored at −80 °C prior to analysis. Glucose and triglycerides (StanBio, Boerne, TX) were measured using enzyme colorimetric assays. Human and mouse FGF21 were measured by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

2.8. Hepatic triglyceride determination

Liver triglycerides were extracted using a modified Folch method. Briefly, ∼100 mg of liver was homogenized in 4 ml of chloroform:methanol (2:1) and incubated overnight at room temperature. 800 μl of 0.9% saline was added. Each sample was then centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min. The organic phase was removed and dried in a vacuum concentrator. Triglyceride content was assayed with the use of a colormetric assay (StanBio, Boerne, TX).

2.9. Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Data sets were analyzed for statistical significance using GraphPad Prism v6.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) using two-way ANOVA and individual comparisons with a Fisher's LSD test. VLDL secretion was analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA. Statistical significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Fructose regulates FGF21 in a ChREBP-dependent manner

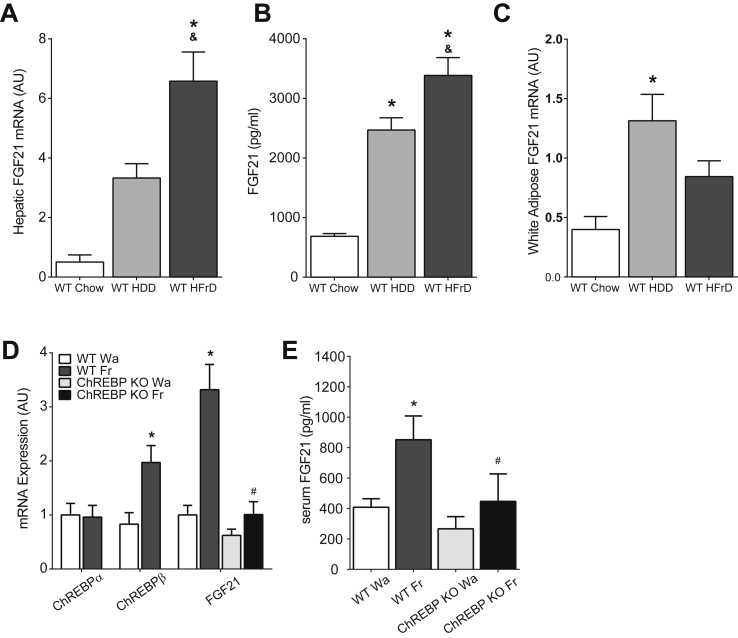

We recently demonstrated that high-fructose feeding (HFrD) more potently stimulates ChREBP activity than high-dextrose feeding (HDD) in mouse liver [12]. We tested the ability of HFrD vs HDD to stimulate FGF21 and observed that hepatic Fgf21 expression is increased 6.5-fold and 13-fold in mice fed HDD or HFrD, respectively (Figure 1A). This is paralleled by 3-fold and 4-fold increases in circulating FGF21 levels (Figure 1B). Fgf21 expression is increased 3-fold in adipose tissue of HDD mice but not significantly increased in adipose tissue of HFrD mice (Figure 1C), indicating that the liver is the source of circulating FGF21 in HFrD mice.

Figure 1.

Fructose regulates Fgf21 in a ChREBP-dependent manner. A) Increased hepatic Fgf21 mRNA expression in mice consuming HFrD for 4 weeks. (n = 5–7/group) B) Fgf21 serum levels in mice consuming HFrD for 4 weeks are also elevated. (n = 5–7/group) C) Adipose Fgf21 gene expression in mice as in A. *P < 0.05 vs Chow, &P < 0.05 vs HDD. D) Hepatic gene expression in mice 30 min after fructose gavage (n = 4–6/group) and E) serum FGF21 levels 1 h after fructose gavage (n = 4–6/group) in WT and ChREBP KO mice. *P < 0.05 versus WT water (Wa), #P < 0.05 versus WT fructose (Fr). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

We also recently showed that in humans, fructose ingestion acutely and robustly stimulates serum FGF21 [33]. In mice, fructose gavage produces an acute 2-fold increase in expression of the novel, potent ChREBP-β isoform (Figure 1D) [32]. Fructose gavage also produced a 3-fold increase in hepatic Fgf21 expression (Figure 1D) and a 2-fold increase in circulating FGF21 (Figure 1E). Thus, the acute regulation of FGF21 by fructose is conserved in both mice and humans. von Holstein-Rathlou and colleagues recently demonstrated that circulating FGF21 increased in wild-type mice challenged for 24 h with sucrose enriched water, but this did not occur in ChREBP knockout (KO) mice, indicating that ChREBP may be required for sucrose-mediated increases in serum FGF21 [31]. However, ChREBP KO mice are intolerant to fructose and rapidly reduce consumption when challenged with diets or solutions containing fructose [12], [13]. Therefore, it is not clear whether the previously reported absence of an increase in FGF21 in ChREBP KO mice challenged with sucrose was the result of reduced sucrose consumption versus the absence of sucrose-stimulated ChREBP-mediated upregulation of Fgf21. To differentiate these possibilities, we employed the gavage paradigm to acutely deliver equivalent amounts of fructose to both wild-type (WT) and ChREBP KO mice. In contrast to WT mice, fructose gavage failed to induce increases in either hepatic expression of Fgf21 (Figure 1D) or circulating FGF21 (Figure 1E) in ChREBP KO mice indicating that ChREBP-mediated transactivation of hepatic Fgf21 is indeed essential for fructose-mediated increases in circulating FGF21.

3.2. FGF21 participates in an adaptive response to fructose consumption

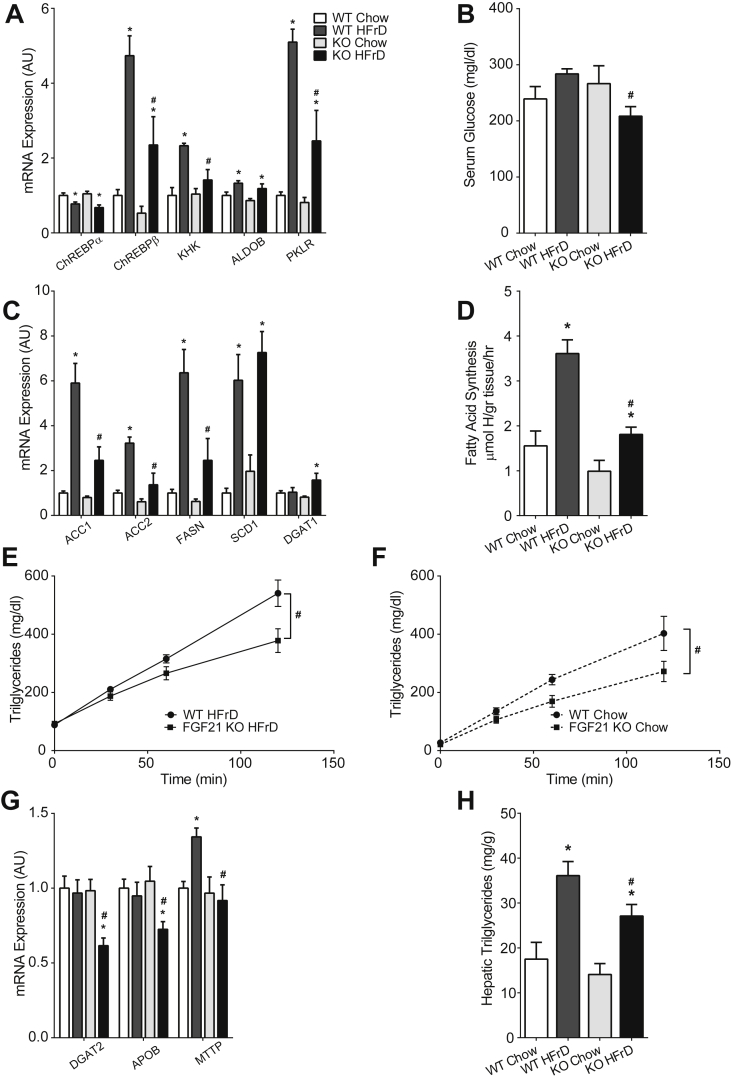

The acute and reproducible response of FGF21 to fructose ingestion suggests that FGF21 might mediate an adaptive metabolic response to fructose ingestion. Consistent with this, FGF21 acts within the central nervous system to regulate sweet-taste preference [30], [31]. To determine whether FGF21 might also play a role regulating peripheral metabolism of ingested sugar or fructose, we fed WT and FGF21 deficient (FGF21 KO) mice a HFrD for 4 weeks, which increased hepatic Fgf21 mRNA expression and circulating FGF21 levels in WT mice (Supplementary Figure 1A and B). HFrD fed WT and FGF21 KO mice gained less weight than their chow fed controls, and body weight did not differ between genotypes (Supplementary Figure 1C). HFrD induced hepatic ChREBP-β expression in WT, but this was significantly attenuated in FGF21 KO mice (Figure 2A) as was the induction of key ChREBP transcriptional targets including ketohexokinase (Khk), a key fructolytic enzyme, and pyruvate kinase (Pklr), a key glycolytic enzyme (Figure 2A). As a significant portion of ingested fructose is converted to glucose in the liver under the influence of ChREBP [12], we assessed circulating glucose levels in these mice. HFrD diet tended to increase serum glucose levels in the WT mice, however, serum glucose was modestly but significantly lower in HFrD FGF21 KO mice (Figure 2B). Because fructose can acutely regulate FGF21 in both mice and humans, we also tested whether FGF21 might acutely regulate ChREBP and metabolic parameters acutely after fructose challenge. After an overnight fast followed by 4 h of HFrD refeeding, the induction of ChREBP-β was diminished and glycemia was lower in FGF21 KO mice (Supplementary Figure 2). Taken together these data indicate that fructose activates ChREBP, which stimulates FGF21 secretion, which, in turn, feeds back and positively contributes to fructose-mediated activation of ChREBP.

Figure 2.

Fgf21 participates in fructose-mediated induction of ChREBP and DNL. A) HFrD diet mediated induction of hepatic ChREBPβ and its transcriptional targets are diminished in FGF21 KO mice. B) Circulating glucose levels are lower in FGF21 KO mice consuming HFrD. C) Attenuated induction of multiple enzymes regulating DNL in the livers of HFrD fed FGF21 KO mice. (A–B, WT Chow & FGF21 KO Chow n = 5/group, WT HFrD & FGF21 KO HFrD n = 7/group) D) In vivo rates of DNL are reduced in FGF21 KO mice (WT Chow n = 4, FGF21 KO Chow n = 5, WT HFrD & FGF21 KO HFrD n = 6/group). VLDL secretion is attenuated in FGF21 KO mice consuming E) HFrD (WT HFrD n = 8, FGF21 KO HFrD n = 9) and F) Chow diet (WT Chow n = 5, FGF21 KO Chow n = 5). This is, in part, underscored by G) reduced expression of enzymes regulating VLDL assembly (WT Chow & FGF21 KO Chow n = 5/group, WT HFrD & FGF21 KO HFrD n = 7/group). Taken together these impairments lead to a net reduction in H) hepatic triglyceride content. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, Chow vs Fructose for each genotype. #P < 0.05, Fructose WT vs Fructose KO.

As ChREBP is a major contributor to sugar-induced hepatic DNL, we hypothesized that FGF21 would also modulate hepatic DNL in response to fructose ingestion. Consistent with this, the expression levels of multiple ChREBP targets and key DNL enzymes were significantly lower in FGF21 KO mice consuming HFrD (Figure 2C). HFrD robustly increased in vivo rates of hepatic DNL in WT mice, but this was abrogated in FGF21 KO mice (Figure 2D). Thus, while FGF21 enhances fatty acid oxidation in the context of fasting or ketogenic diets [15], [19], [34], in this context, FGF21 promotes fatty acid synthesis.

Fructose consumption has multiple actions on hepatic lipid metabolism. It enhances DNL, and it can also enhance packaging and secretion of liver fat as VLDL [35]. Increased DNL might enhance steatosis, whereas fructose-mediated increases in VLDL secretion might decrease steatosis and contribute to hypertriglyceridemia. To determine whether FGF21 also plays a role in VLDL secretion, we assessed the rate of serum triglyceride accumulation following inhibition of lipoprotein lipase in WT and FGF21 KO mice consuming chow versus HFrD. In WT mice, HFrD increased VLDL secretion (402.8 mg/dl ± 58.8 vs 540.8 ± 45.53, P = 0.008) (Figure 2E and F). Serum triglyceride accumulation was significantly attenuated in FGF21 KO mice on both diets (Figure 2E and F). This reduction may be in part due to impaired expression of enzymes required for VLDL secretion and assembly in FGF21 KO on HFrD (Figure 3G). Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein (Mttp), a key factor in VLDL secretion increased with high-fructose feeding, and this was attenuated in FGF21 KO consistent with other ChREBP transcriptional targets. Diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 (Dgat2), which catalyzes the final step in TG synthesis, and apolipoprotein B (Apob), a key apolipoprotein for VLDL packaging, were not upregulated with fructose feeding but were downregulated in fructose-fed FGF21 KO. This indicates that FGF21 may have ChREBP-independent effects on hepatic lipid homeostasis in this nutritional context.

Figure 3.

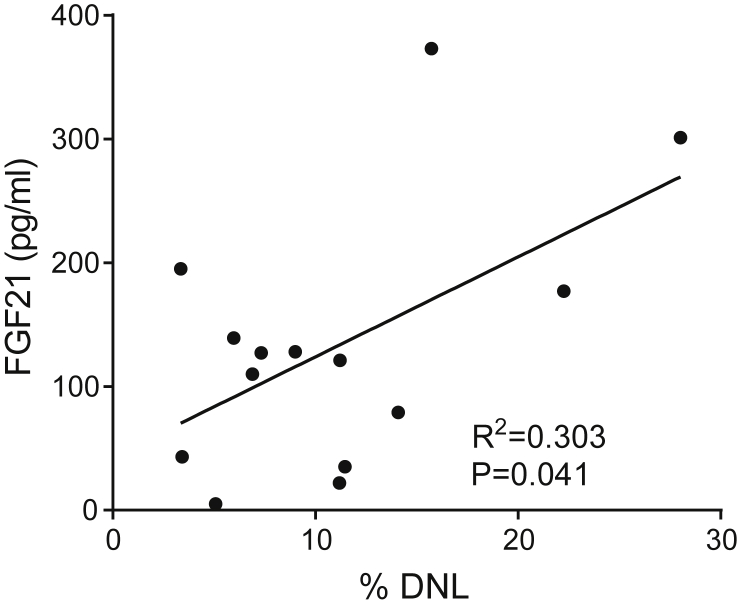

In humans, circulating Fgf21 correlates with DNL. Graph showing regression analysis between basal circulating FGF21 levels and basal rates of de novo lipogenesis in human subjects (n = 14).

The degree of hepatic steatosis is determined by the balance between liver triglyceride accretion and utilization either via oxidation or secretion as VLDL. Our results indicate that on HFrD, FGF21 promotes fatty acid synthesis which enhances steatosis, but also promotes VLDL secretion, which might reduce steatosis. To assess FGF21's net effect on steatosis, we measured hepatic triglyceride levels. HFrD increased liver fat 2.1-fold in WT (Figure 2H). HFrD increased steatosis by 1.6-fold in FGF21 KO, but steatosis remained significantly lower in FGF21 KO compared to WT. This indicates that FGF21 is a net contributor to the development of hepatic steatosis in mice on HFrD. These results also demonstrate a complex role for FGF21 in regulating distinct aspects of hepatic carbohydrate and lipid metabolism that is highly dependent on nutritional context.

3.3. In humans, circulating FGF21 correlates with DNL

Circulating FGF21 is increased in humans with hepatic steatosis [23] and increased DNL contributes to steatosis. As both circulating FGF21 and DNL appear to be regulated through ChREBP, we hypothesized that circulating FGF21 and DNL rates should correlate in human subjects. To test this, we examined circulating FGF21 levels in a human cohort where DNL had previously been characterized (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 1, and [7]). Indeed, serum FGF21 levels correlate with DNL rates in this cohort (R = 0.55, P = 0.041) (Figure 3). Thus, ChREBP activation provides a plausible mechanistic explanation for the observed association between circulating FGF21 and hepatic steatosis in human populations. This conclusion might be further substantiated by examining the relationship between ChREBP activity and FGF21 expression in human liver biopsy samples, but such samples were not available from this cohort.

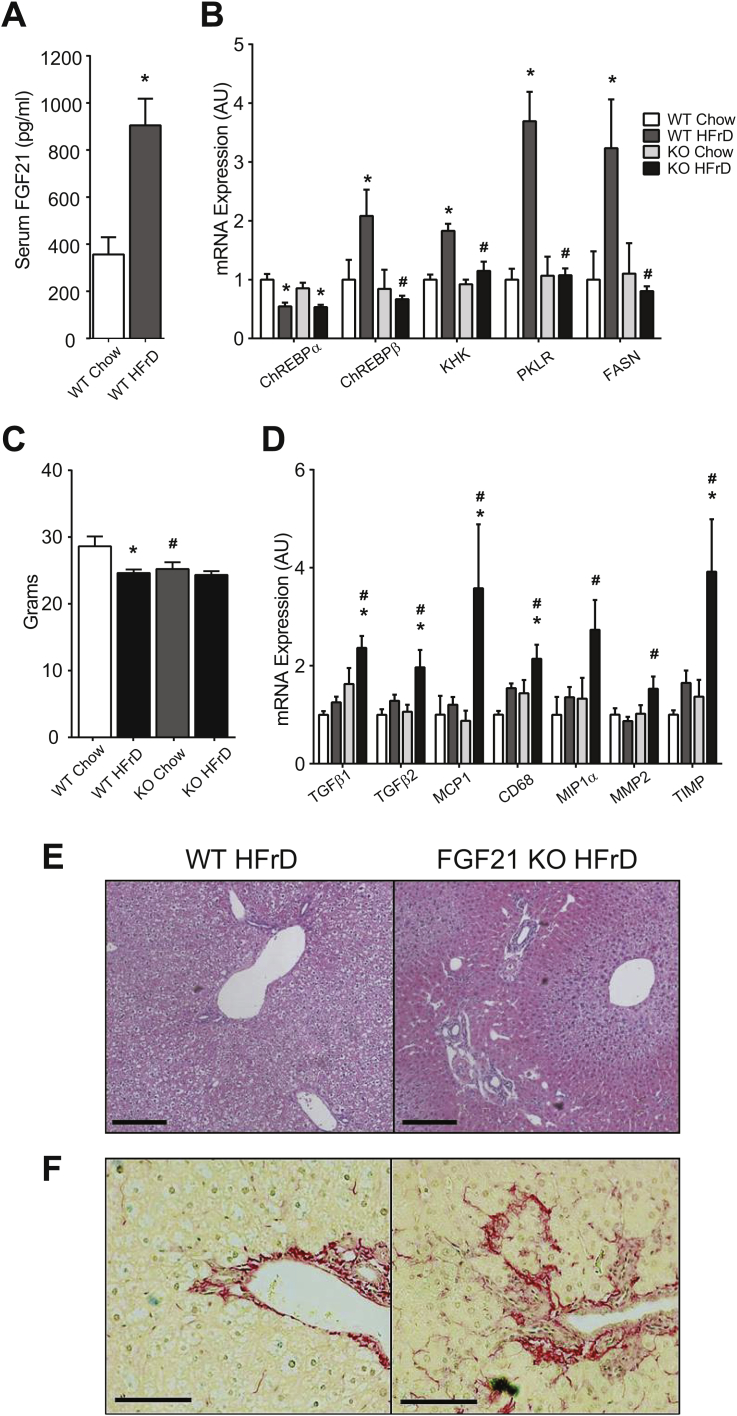

3.4. Fructose causes liver disease in the absence of FGF21

We next asked whether the altered molecular response to fructose in FGF21 KO has any long-term adverse health consequences. After 8 weeks on HFrD, serum FGF21 levels are highly elevated in WT mice (Figure 4A). Fructose-mediated increases in ChREBP-β and its targets are abrogated in FGF21 KO (Figure 4B). These differences in gene expression occur without a difference in body weight between WT and FGF21 KO mice on HFrD (Figure 4C). We also noted a significant increase in the expression of multiple markers of inflammation such as the macrophage chemoattractant MCP1 and the Kupffer cell marker CD68 selectively in HFrD FGF21 KO. Early stage markers of fibrosis and stellate cell activation (TGFβ, MMP2 and TIMP) were also increased in HFrD FGF21 KO (Figure 4D). Histologically, HFrD FGF21 KO livers showed increased lipid droplets in zone 3 despite overall lower triglyceride content (Figure 4E). At termination, 6 out of 9 FGF21 KO mice consuming HFrD demonstrated small, stiff livers suggestive of fibrosis, whereas this was not observed in any of the WT mice. We examined histology for fibrosis in three mice of each group and confirmed the presence of biliary ductal fibrosis in HFrD FGF21 KO. No fibrosis was observed in WT mice (Figure 4F). Thus, FGF21 is critical to maintain normal liver health when challenged with fructose.

Figure 4.

Fructose consumption causes liver disease in the absence of Fgf21. A) Elevated serum FGF21 levels after 8 weeks of HFrD consumption. B) Fructose-mediated induction of hepatic ChREBP-β mRNA and ChREBP gene targets are diminished in FGF21 KO mice. C) Body weights and D) markers of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in the livers of HFrD FGF21 KO mice and controls (A–D, WT Chow n = 5, KO Chow n = 6, WT HFrD & KO HFrD n = 9/group). Representative histology showing E) localization of lipid to zone 3 in FGF21-KO mice and F) increased fibrosis by Sirius stain in FGF-21 KO mice compared to WT when consuming a high fructose diet. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, Compared to chow within genotype. #P < 0.05, compared to WT within diet.

In summary, we have identified a ChREBP-FGF21 signaling axis that is required for an adaptive metabolic response to fructose ingestion. This signaling axis may contribute to the observed association between circulating FGF21 and steatosis or metabolic syndrome in human populations. Moreover, FGF21 appears to exert a protective effect on the liver in the setting of increased sugar ingestion. These results raise the interesting prospect that relative FGF21 deficiency or obesity related FGF21 resistance may contribute to NAFLD progression. Our findings will motivate additional studies to investigate whether FGF21 might be used therapeutically to diminish the risks associated with NAFLD.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by P30DK057521 (MAH), R01DK100425 (MAH), R01DK028082 (EMF), General Clinical Research Center grant (M01-RR00102), and a Clinical Center for Translational Science award (UL1RR024143).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2016.11.008.

Contributor Information

Eleftheria Maratos-Flier, Email: emaratos@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Mark A. Herman, Email: mark.herman@duke.edu.

Conflict of interest

MKH is a founder and Chairman of the Scientific Advisory Board of KineMed, Inc.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Bray G.A., Nielsen S.J., Popkin B.M. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79(4):537–543. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rinella M.E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313(22):2263–2273. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zelber-Sagi S., Nitzan-Kaluski D., Goldsmith R., Webb M., Blendis L., Halpern Z. Long term nutritional intake and the risk for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a population based study. Journal of Hepatology. 2007;47(5):711–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma J., Fox C.S., Jacques P.F., Speliotes E.K., Hoffmann U., Smith C.E. Sugar-sweetened beverage, diet soda, and fatty liver disease in the Framingham Heart Study cohorts. Journal of Hepatology. 2015;63(2):462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanhope K.L., Schwarz J.M., Keim N.L., Griffen S.C., Bremer A.A., Graham J.L. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119(5):1322–1334. doi: 10.1172/JCI37385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarz J.M., Noworolski S.M., Wen M.J., Dyachenko A., Prior J.L., Weinberg M.E. Effect of a high-fructose weight-maintaining diet on lipogenesis and liver fat. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;100(6):2434–2442. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hudgins L.C., Parker T.S., Levine D.M., Hellerstein M.K. A dual sugar challenge test for lipogenic sensitivity to dietary fructose. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(3):861–868. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly K.L., Smith C.I., Schwarzenberg S.J., Jessurun J., Boldt M.D., Parks E.J. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(5):1343–1351. doi: 10.1172/JCI23621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lambert J.E., Ramos-Roman M.A., Browning J.D., Parks E.J. Increased de novo lipogenesis is a distinct characteristic of individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(3):726–735. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayes P.A. Intermediary metabolism of fructose. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1993;58(5 Suppl):754S–765S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.5.754S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanhope K.L., Schwarz J.M., Havel P.J. Adverse metabolic effects of dietary fructose: results from the recent epidemiological, clinical, and mechanistic studies. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2013;24(3):198–206. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283613bca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim M.S., Krawczyk S.A., Doridot L., Fowler A.J., Wang J.X., Trauger S.A. ChREBP regulates fructose-induced glucose production independently of insulin signaling. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2016 Nov 1;126(11):4372–4386. doi: 10.1172/JCI81993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iizuka K., Bruick R.K., Liang G., Horton J.D., Uyeda K. Deficiency of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP) reduces lipogenesis as well as glycolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(19):7281–7286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401516101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herman M.A., Samuel V.T. The sweet path to metabolic demise: fructose and lipid synthesis. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2016 Oct;27(10):719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badman M.K., Pissios P., Kennedy A.R., Koukos G., Flier J.S., Maratos-Flier E. Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by PPARalpha and is a key mediator of hepatic lipid metabolism in ketotic states. Cell Metabolism. 2007;5(6):426–437. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kharitonenkov A., Shiyanova T.L., Koester A., Ford A.M., Micanovic R., Galbreath E.J. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(6):1627–1635. doi: 10.1172/JCI23606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markan K.R., Naber M.C., Ameka M.K., Anderegg M.D., Mangelsdorf D.J., Kliewer S.A. Circulating FGF21 is liver derived and enhances glucose uptake during refeeding and overfeeding. Diabetes. 2014;63(12):4057–4063. doi: 10.2337/db14-0595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kharitonenkov A., DiMarchi R. FGF21 revolutions: recent advances illuminating FGF21 biology and medicinal properties. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;26(11):608–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potthoff M.J., Inagaki T., Satapati S., Ding X., He T., Goetz R. FGF21 induces PGC-1alpha and regulates carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism during the adaptive starvation response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(26):10853–10858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904187106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inagaki T., Dutchak P., Zhao G., Ding X., Gautron L., Parameswara V. Endocrine regulation of the fasting response by PPARalpha-mediated induction of fibroblast growth factor 21. Cell Metabolism. 2007;5(6):415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim H., Mendez R., Zheng Z., Chang L., Cai J., Zhang R. Liver-enriched transcription factor CREBH interacts with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha to regulate metabolic hormone FGF21. Endocrinology. 2014;155(3):769–782. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park J.G., Xu X., Cho S., Hur K.Y., Lee M.S., Kersten S. CREBH-FGF21 axis improves hepatic steatosis by suppressing adipose tissue lipolysis. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:27938. doi: 10.1038/srep27938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dushay J., Chui P.C., Gopalakrishnan G.S., Varela-Rey M., Crawley M., Fisher F.M. Increased fibroblast growth factor 21 in obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(2):456–463. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christodoulides C., Dyson P., Sprecher D., Tsintzas K., Karpe F. Circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 is induced by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists but not ketosis in man. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;94(9):3594–3601. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galman C., Lundasen T., Kharitonenkov A., Bina H.A., Eriksson M., Hafstrom I. The circulating metabolic regulator FGF21 is induced by prolonged fasting and PPARalpha activation in man. Cell Metabolism. 2008;8(2):169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez J., Palou A., Pico C. Response to carbohydrate and fat refeeding in the expression of genes involved in nutrient partitioning and metabolism: striking effects on fibroblast growth factor-21 induction. Endocrinology. 2009;150(12):5341–5350. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iizuka K., Takeda J., Horikawa Y. Glucose induces FGF21 mRNA expression through ChREBP activation in rat hepatocytes. FEBS Letters. 2009;583(17):2882–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu A.Y., Workalemahu T., Paynter N.P., Rose L.M., Giulianini F., Tanaka T. Novel locus including FGF21 is associated with dietary macronutrient intake. Human Molecular Genetics. 2013;22(9):1895–1902. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka T., Ngwa J.S., van Rooij F.J., Zillikens M.C., Wojczynski M.K., Frazier-Wood A.C. Genome-wide meta-analysis of observational studies shows common genetic variants associated with macronutrient intake. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2013;97(6):1395–1402. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.052183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talukdar S., Owen B.M., Song P., Hernandez G., Zhang Y., Zhou Y. FGF21 regulates sweet and alcohol preference. Cell Metabolism. 2016;23(2):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Holstein-Rathlou S., BonDurant L.D., Peltekian L., Naber M.C., Yin T.C., Claflin K.E. FGF21 mediates endocrine control of simple sugar intake and sweet taste preference by the liver. Cell Metabolism. 2016;23(2):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herman M.A., Peroni O.D., Villoria J., Schon M.R., Abumrad N.A., Bluher M. A novel ChREBP isoform in adipose tissue regulates systemic glucose metabolism. Nature. 2012;484(7394):333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature10986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dushay J.R., Toschi E., Mitten E.K., Fisher F.M., Herman M.A., Maratos-Flier E. Fructose ingestion acutely stimulates circulating FGF21 levels in humans. Molecular Metabolism. 2015;4(1):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher F.M., Chui P.C., Nasser I.A., Popov Y., Cunniff J.C., Lundasen T. Fibroblast growth factor 21 limits lipotoxicity by promoting hepatic fatty acid activation in mice on methionine and choline-deficient diets. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(5):1073–1083 e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zavaroni I., Chen Y.D., Reaven G.M. Studies of the mechanism of fructose-induced hypertriglyceridemia in the rat. Metabolism. 1982;31(11):1077–1083. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.