Abstract

Objective: Despite several works have described the usefulness of negative pressure therapy (NPT) in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), no studies have reported its ability in the proteases modulation in DFUs. The aim of this work was to evaluate the role of NPT as a protease-modulating treatment in DFUs.

Approach: We conducted a prospective study of a series of diabetic patients affected by chronic DFUs. Each ulcer was assessed for matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) activity with a protease status diagnostic test at the baseline and after 2 weeks of NPT.

Results: Four patients were included. All patients had type 2 diabetes with a disease duration of ≈20 years. A1c was 79.5 ± 15.3 mmol/mol. Ulcer area was >5 cm2 in all cases. All wounds showed elevated protease activity (EPA) at the baseline. After 2 weeks, all patients showed a normalization of MMPs activity.

Innovation: NPT showed its effectiveness in the reduction of EPA in chronic DFUs.

Conclusion: This study confirms the role of NPT in the positive modulation of protease activity also in chronic DFUs.

Keywords: : foot ulcers, negative pressure, chronic wounds

Valentina Izzo, MD

Introduction

Physiological wound healing requires a complex series of overlapping phases: (1) hemostasis, (2) inflammation, (3) proliferation and (4) remodeling.1 Each alteration of this process leads to impaired wound healing.

Although acute wounds follow an orchestrated progress through all the healing phases, the inflammatory phase appears prolonged in chronic wounds, leading to alteration of the balance between promoting healing factors and nonhealing factors.2

Proteases have a main role in this process. They are enzymes involved in the removal of damaged tissue, especially the extracellular matrix (ECM); they break down the capillaries basement membrane to allow the migration of vascular endothelial cells; they facilitate cellular movement through the collagen matrix, by cutting the attachment of the cell membrane to the matrix. Moreover, proteases are needed for contraction and final ECM remodeling.3

Elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and reduced levels of their endogenous tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) have been shown in chronic wounds.3–6 It has been hypothesized that increased activity of these enzymes could cause excessive degradation of ECM proteins, interfering in a key passage of wound healing.

Many studies focused on dressings able to reduce levels of MMPs.7–14

Among these, negative pressure therapy (NPT) plays an interesting role. NPT is a noninvasive therapy system that applies controlled negative pressure using a vacuum-assisted closure device.15 Its role in the management of the wound bed environment has been widely described.16–21 Some authors reported a reduction in expression of MMPs in wounds of various etiologies.22–25

Clinical Problem Addressed

The aim of our study is to evaluate the efficacy of NPT to reduce MMPs activity in diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) with elevated protease activity (EPA).

Materials and Methods

We conducted a prospective study of a series of diabetic patients presenting at the Diabetic Foot Unit of the University of Rome Tor Vergata with an extensive foot tissue loss caused by previous infection or gangrene. The study follows the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

• Chronic wounds (relative wound area reduction at 4 weeks <50%).26

• A2 foot ulcer as defined by the University of Texas Diabetic Wound Classification (no ischemia/no infection/no bone exposure).

• Absence of clinical signs of infection (purulent secretion, pain, edema, perilesional cellulitis, and malodorous wound).

• Adequate blood flow established by transcutaneous oximetry (TcPO2)>30 mmHg.27

• Absence of necrotic tissues.

• Adequate off loading.

• Any treatment with local or systemic antibiotics.

• Any local or systemic steroids therapy.

Each patient was assessed for sex, age, type, and duration of diabetes, glycated hemoglobin (A1c) levels, serum creatinine levels, nutritional values, and previous lower limb revascularization. Local blood perfusion and peripheral neuropathy were evaluated by TcPO2 and vibration perception threshold, respectively.

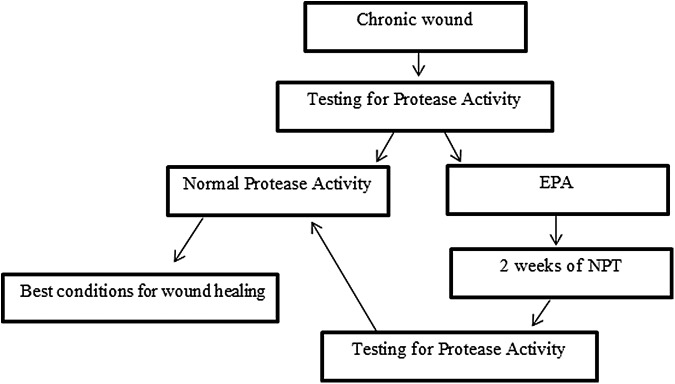

MMPs activity of each ulcer was evaluated by a protease test at the baseline and after 2 weeks of NPT Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the study design.

Protease test

To identify EPA wounds, we used the WOUNDCHEK™ Protease Status diagnostic test. It is an immunochromatographic test for the qualitative assessment of human neutrophil-derived inflammatory protease activity from a wound fluid swab sample taken from wounds.

We used a standardized specimen collection protocol (Serena's technique) to ensure an optimal collection of the wound fluid.28 The test took ∼15 min to provide results.

Negative pressure wound therapy

Owing to the hospital availability, KCI V.A.C. Ulta™ Negative Pressure Wound Therapy System (Kinetic Concepts Incorporated, San Antonio, TX) was used during patient admission. During KCI V.A.C. Ulta application, the supplied black sponge was used and sealed at 125 mmHg of continuous pressure. All NPT systems were applied according to the KCI guidelines and changed two times per week. All NPT systems were ongoing for 2 weeks.

Results

A total of four patients were included. This case series included three men and one woman (mean age 67.25 years).

All patients had type 2 diabetes with a disease duration of ≈20 years. A1c was 79.5 ± 15.3 mmol/mol. Ulcer area was >5 cm2 in all cases. TcPO2 values were 42.7 ± 11.7 mmHg. Percutaneous angioplasty had been previously performed in all patients. The patients’ characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline wound characteristics

| Sex (% males) | 75 |

| Age (years) | 67.25 ± 5.9 |

| Type 2 diabetes (%) | 100 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 23.5 ± 3.1 |

| A1c (mmol/mol) | 79.5 ± 15.3 |

| Ulcer size >5 cm2 (%) | 100 |

| TcPO2 (mmHg) | 42.7 ± 11.7 |

| VPT | 26 ± 19.8 |

| Previous PTA (%) | 100 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 4.4 ± 3.0 |

| Dialysis patients (%) | 50 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 2.4 ± 0.2 |

| Transferrin (mg/dL) | 124.5 ± 29.2 |

| Prealbumin (mg/dL) | 11.8 ± 3.1 |

| Retinol binding protein (mg/dL) | 4.7 ± 1.3 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 164.2 ± 38.3 |

PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; VPT, vibration perception threshold.

All wounds showed EPA at the baseline. After 2 weeks of NPT, all patients with EPA showed normalization of MMPs activity.

Discussion

Over the past years, several researches have been focused on the usefulness of NPT in the treatment of chronic wounds, including DFUs.29–34

Nevertheless only few articles described the NPT influence on MMPs activity.22–25

Greene et al. described the reduction in MMP-9/neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, MMP-9, latent, and active MMP-2 activity by 15% to 76% determined by zymography in three patients (1 DFU) after 2 weeks of NPT.22 Moues et al. showed significantly lower levels of pro-MMP-9 and higher ratio of MMP-9/TIMP-1 in 15 NPT-treated wounds than in 18 conventional treated wounds. Wound fluid samples were collected daily for up to 10 days using a sterile porous filter, and quantitative measurements of pro-MMP-9 and TIMP-1 levels were analyzed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).23

Stechmiller et al. reported significant decreased tumor necrosis factor-α levels after 7 days of NPT in six patients with pressure ulcers. Instead, they did not find decreased levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), MMP-2, MMP-3, or TIMP-1 from the baseline. The wound fluid was collected directly from the drainage tube and quantitative measurements were performed by ELISA.24

Otherwise, Shi et al. reported a reduction in MMP-2 levels in chronic wounds treated with NPT for 7 days.25

In our knowledge, studies regarding the role of NPT on MMPs modulation in DFUs are not available.

In our small pilot study, we evaluated MMPs activity in chronic DFUs detected by a noninvasive diagnostic test.

In this study, we applied NPT in patients with EPA. After 2 weeks of treatment, we repeated the protease status diagnostic test that showed, in all cases, normal MMPs activity.

Our data seems to confirm the role of NPT in the modulation of MMPs activity in patients affected by DFUs.

According to a recent study, EPA is associated with 90% probability of nonhealing without an appropriate intervention.35

This finding is in line with our previous study, in which we found a strict relationship between MMPs activity and the dermal graft integration.36

The evaluation and modulation of MMPs activity are a key point in the concept of “wound bed preparation.”

In addition to NPT, several researches are focused on dressings able to modulate MMPs activity. Oxidized regenerated cellulose/collagen matrix (ORC/collagen matrix) has been reported to improve the wound microenvironment by adsorbing wound exudate and retaining proteases within the dressing structure.7–13 A randomized controlled trial demonstrated the superiority on modulating proteases of a wound dressing based on the Lipido-Colloid Technology, impregnated with a Nano-Oligo Saccharide Factor compared with an ORC/collagen matrix.14

A systematic review of the clinical evidence on protease-modulating dressing and researches that compare these devices would be useful in providing an overview of the appropriate treatment to achieve optimal healing for chronic wounds.

Innovation

DFUs are among the most expensive wounds to treat. The analysis of wound bed environment, particularly MMPs activity, needs to be considered before to define the therapeutic strategy. In case of EPA wounds, protease-modulating therapy needs to be applied. NPT is a valid option to normalize MMPs activity to make a suitable environment to expensive dressing such as dermal graft. This study confirms the usefulness of NPT to modulate MMPs activity in chronic DFUs. Further studies with larger samples are needed to support this evidence.

Key Findings.

• EPA has been correlated with delayed wound healing in chronic wounds of various etiologies.

• The analysis of wound bed environment, particularly MMPs activity, needs to be considered before planning the therapeutic strategy.

• Several works have described the usefulness of NPT in the treatment of DFUs.

• Our work shows the skill of NPT to reduce EPA also in chronic DFUs.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- DFUs

diabetic foot ulcers

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EPA

elevated protease activity

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- NPT

negative pressure therapy

- ORC

oxidized regenerated cellulose

- TcPO2

transcutaneous oximetry

- TIMPs

tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

Acknowledgment and Funding Source

The study follows the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

No competing financial interests exist. The content of this article was expressly written by the authors listed. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Valentina Izzo, MD, Resident in Postgraduate Program in Endocrinology, University of Rome Tor Vergata. Conception, design of the study, collection of the data, writing of the text. Marco Meloni, MD, Resident in Postgraduate Program in Geriatric, University of Rome Tor Vergata. Acquisition of data and critical revision. Laura Giurato, MD, PhD, Diabetic Foot Unit of the University of Rome Tor Vergata. Acquisition of data. Valeria Ruotolo, MD, Diabetic Foot Unit of the University of Rome Tor Vergata. Acquisition of data. Luigi Uccioli, MD, Associate Professor, Chief of the Diabetic Foot Unit of the University of Rome Tor Vergata. Conception and critical revision.

References

- 1.Clark R, ed. Wound repair: overview and general considerations. In: Clark R, ed. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Repair. New York: Plenum Press, 1998:3–50 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tecilazich F, Dinh T, Veves A. Treating diabetic ulcers. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2011;12:593–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson D, Cullen B, Legerstee R, Harding KG, Schultz G. MMPs made easy. www.woundsinternational.com/media/issues/61/files/content_21.pdf (accessed November14, 2014)

- 4.Wounds International. International consensus. The role of protease in wound diagnostics. An expert working group review. www.woundsinternational.com/media/issues/419/files/content_9869.pdf (accessed May19, 2011)

- 5.Visse R, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: structure, function, and biochemistry. Circulation Res 2003;92:827–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazaro JL, Izzo V, Meaume S, et al. Elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases and chronic wound healing: an updated review of clinical evidence. J Wound Care 2016;25:277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen B, Watt P, Lundqvist C, et al. The role of oxidized regenerated cellulose/collagen in chronic wound repair and its potential mechanism of action. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2002;34:1544–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullen B, Smith Rachel , McCulloch E, et al. Mechanism of action of PROMOGRAN, a protease modulating matrix, for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen 2002;10:16–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzkau M, Tautenhahn J, Lehnert H, Lobmann R. Expression of matrix-metalloproteases in the fluid of chronic diabetic foot wounds treated with a protease absorbent dressing. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2011;119:286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kloeters O, Unglaub F, de Laat E, et al. Prospective and randomised evaluation of the protease-modulating effect of oxidised regenerated cellulose/collagen matrix treatment in pressure sore ulcers. Int Wound J 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1111/iwj.12449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottrup F, Cullen BM, Karlsmark T, et al. Randomized controlled trial on collagen/oxidized regenerated cellulose/silver treatment. Wound Repair Regen 2013;21:216–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veves A, Sheehan P, Pham HT. A randomised, controlled trial of Promogran (a collagen/oxidised regenerated cellulose dressing) vs standard treatment in the management of diabetic foot ulcers. Arch Surg 2002;137:822–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lázaro-Martínez JL, García-Morales E, Beneit-Montesinos JV, et al. Randomised comparative trial of a collagen/oxidised regenerated cellulose dressing in the treatment of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. (article in Spanish). Cir Esp 2007;82:27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmutz JL, Meaume S, Fays S, et al. Evaluation of the nano-oligosaccharide factor lipido-colloid matrix in the local management of venous leg ulcers: results of a randomised, controlled trial. Int Wound J 2008;5:172–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nain PS, Uppal SK, Garg R, et al. Role of negative pressure wound therapy in healing of diabetic foot ulcers. J Surg Tech Case Rep 2011;3:17–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gustafsson R, Sjogren J, Ingenansson R. Understanding topical negative pressure therapy: topical negative pressure in wound management. EWMA position document. www.woundsinternational.com/media/issues/84/files/content_46.pdf (accessed May, 2009)

- 17.Joseph E, Hamori CA, Bergman S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus standard therapy of chronic non-healing wounds. Wounds 2000;12:60–67 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timmers MS, Le Cessie S, Banwell P, et al. The effects of varying degrees of pressure delivered by negative-pressure wound therapy on skin perfusion. Ann Plast Surg 2005;55:665–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, Chen S, Li X. The experimental study of the effects of vacuum-assisted closure on edema and vessel permeability of the wound. Chin J Clin Rehab 2003;7:1244–1245 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moues CM, Vos MC, Van den Bemd GJ, et al. Bacterial load in relation to vacuum assisted closure wound therapy: a prospective randomized trial. Wound repair Reg 2004;12:11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan SY, Wong KL, Lim JX, et al. The role of Renasys-GO in the treatment of diabetic lower limb ulcers: a case series. Diabet Foot Ankle 2014;5:24718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene AK, Puder M, Roy R, et al. Microdeformational wound therapy: effects on angiogenesis and matrix metalloproteinases in chronic wounds of 3 debilitated patients. Ann Plast Surg 2006;56:418–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moues CM, Van Toorenenbergen AW, Heule F, et al. The role of topical negative pressure in wound repair: expression of biochemical markers in wound fluid during wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:488–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stechmiller JK, Kilpadi DV, Childress B, et al. Effect of vacuum-assisted closure therapy on the expression of cytokines and proteases in wound fluid of adults with pressure ulcers. Wound Repair Regen 2006;14:371–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi B, Chen S, Zhang P, et al. Effects of vacuum-assisted closure on the expression of MMP-1, MMP-2 and MMP-13 mRNA in human granulation wounds. (Chinese). Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2003;19:279–281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheehan P, Jones P, Caselli A, et al. Percent change in wound area of diabetic foot ulcers over a 4-week period is a robust predictor of complete healing in a 12-week prospective trial. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1879–1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA. Inter-Society Consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007;33:S73–S108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serena TE. Development of a novel technique to collect proteases from chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care 2014;3:729–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meloni M, Izzo V, Vainieri E, et al. Management of negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. World J Orthop 2015;18:387–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guffanti A. Negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review of the literature. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41:233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Hu ZC, Chen D, et al. Effectiveness and safety of negative-pressure wound therapy of diabetic foot ulcers: a meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;134:141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaidhya N, Panchal A, Anchalia MM. A new cost-effective method of NPWT in diabetic foot wound. Indian J Surg 2015;77:525–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA; Diabetic Foot Study Consortium. Negative pressure wound therapy after partial diabetic foot amputation: a multicenter, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;366:1704–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hasan MY, Teo R, Nather A. Negative-pressure wound therapy for management of diabetic foot wounds: a review of the mechanism of action, clinical applications, and recent developments. Diabetic Foot Ankle 2015;6:27618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serena T, Cullen B, Bayliff S, et al. Protease activity levels associated with healing status of chronic wounds. Poster presentation at Wounds UK, Harrogate, 2011. http://tinyurl com/khmapae (last accessed February17, 2015)

- 36.Izzo V, Meloni M, Vainieri E, et al. High matrix metalloproteinases levels are associated with dermal graft failure in diabetic foot ulcers. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2014;13:191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]