Abstract

Artificial transformation is typically performed in the laboratory by using either a chemical (CaCl2) or an electrical (electroporation) method. However, laboratory-scale lightning has been shown recently to electrotransform Escherichia coli strain DH10B in soil. In this paper, we report on the isolation of two “lightning-competent” soil bacteria after direct electroporation of the Nycodenz bacterial ring extracted from prairie soil in the presence of the pBHCRec plasmid (Tcr, Spr, Smr). The electrotransformability of the isolated bacteria was measured both in vitro (by electroporation cuvette) and in situ (by lightning in soil microcosm) and then compared to those of E. coli DH10B and Pseudomonas fluorescens C7R12. The electrotransformation frequencies measured reached 10−3 to 10−4 by electroporation and 10−4 to 10−5 by simulated lightning, while no transformation was observed in the absence of electrical current. Two of the isolated lightning-competent soil bacteria were identified as Pseudomonas sp. strains.

Bacterial survival can be considered a successful adaptation to changing environmental conditions. Antibiotic resistance and xenobiotic degradation are common examples of the adaptability of the bacterial community (7, 17). Horizontal gene transfer among bacteria has influenced both rapid environmental adaptation and slow species evolution processes (7, 27). Genetic transformation, described as the stable acquisition of exogenous DNA, has been commonly divided into natural and artificial transformations. Natural transformation (5, 18) is an active process of DNA uptake requiring specific genes and a competence state in bacteria. Artificial transformation is considered a passive process requiring chemical (e.g., salt) or electrical (e.g., electroporation) methods in order to affect the cellular membrane and allow DNA introduction. Electroporation is commonly used in laboratories to introduce DNA into bacterial, fungal, plant, or animal cells by subjecting cells to an electric field (10, 20, 22, 26). Nonpermanent pores are formed in the lipid bilayer and other components of the cell membrane (19). While electrotransformation can be used on a large range of cells, the electrotransformation of bacteria often differs among species and generally requires some cell-specific preparation.

While horizontal gene transfer has been shown to occur in situ (9, 14, 18), the distinction between natural and artificial transformation has weakened due to observations of the influence of natural salt or electrical discharges on bacterial transformations in situ. The possible salt-dependent transformation of Escherichia coli strains was described when an E. coli strain, which was incompetent in the absence of salt, underwent chemical transformation in calcareous freshwater (3). In soil, salt concentrations are described as compatible with the induction of a competent phase (18). In addition, Demanèche et al. (8) showed that the electrical parameters occurring during electroporation (in vitro) were similar to those in soil microcosms subjected to lightning-mediated current injection (in situ). Moreover, these authors provided evidence for lightning-mediated gene transfer (electrotransformation) of an E. coli strain in sterile soil. However, the possibility of soil bacteria capable of lightning-induced electroporation was not investigated.

The aim of this work was to isolate lightning-transformable soil bacteria. Thus, we used the electroporation technique on the Nycodenz-extracted bacterial community with a selective plasmid to isolate electrotransformable soil bacteria, which were subsequently tested for their ability to incorporate free DNA when exposed to laboratory-scale lightning in soil microcosms.

Isolation of electrocompetent soil bacteria.

Improvement of cell extraction methodology for soil genomic approaches has focused on maintaining the greatest bacterial diversity possible. The dispersion of the soil particles and the separation of the cells from soil particles by centrifugation constitute the two crucial steps for direct cell extraction (15, 25). Among the different methodologies tested, the high-speed centrifugation method based on Nycodenz density gradient centrifugation provided the best results (1, 16). Soil-derived cell suspensions obtained by the Nycodenz gradient method have been shown to be representative of the original community (6, 12, 24) with minimal effects on cell integrity and physiology (13, 16, 21). The Nycodenz-mediated extraction of bacteria from the soil matrix was performed as previously described (6). Soil from Montrond constituted the source of the bacterial soil community since it provided a high density of bacteria compared to soil from Côte Saint-André, for which the Nycodenz ring was difficult to obtain. Nycodenz-extracted cells (40 μl) were electroporated in the presence of the pBHCRec plasmid (400 ng) in a 0.2-cm-gap electroporation cuvette (Equibio, Ashford, United Kingdom) with one pulse (Gene Pulser II; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) at 12.5 kV/cm, 200 Ω, and 25 μF. The pBHCRec plasmid (Table 1) was constructed by introducing the PvuII DNA fragment (4,493 bp) from plasmid pLEPO1 into the SmaI site of the broad-host-range plasmid pBBR1MCS-3 (Table 1). The pBHCRec transformants were screened at 28°C on Luria-Bertani medium (0.5% NaCl) or 1/10 Trypticase soy broth based on these plasmid markers: streptomycin, 100 μg/ml; spectinomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France), 75 μg/ml; and tetracycline (Boehringer Mannheim France SA, Meylan, France), 20 μg/ml. Two fungicidal drugs (nystatin [50 μg/ml] and cycloheximide [200 μg/ml]; ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Aurora, Ohio) were also required to avoid growth of the vegetative forms of spores present in the Nycodenz cell suspension. Two colonies (Ee2.1 and Ee2.2) were isolated after 2 days during the first experiment; one colony (N3) was isolated after 4 days during the second experiment. Cell-DNA mixtures without electrical discharge (natural transformation) and cells alone with and without electrical discharge (spontaneous mutation and native resistant) were used for control experiments. While all of the controls were negative after 2 days, 20 morphologically similar colonies were detected after 4 days. These colonies did not contain the plasmid. The N3 strain was selected based on its morphological difference with the spontaneous antibiotic-resistant colonies. The high number of resistant colonies on 1/10 Trypticase soy broth medium prevented the isolation of any transformants. Other more appropriate plasmids for better discrimination between natural resistance bacteria and electrotransformants are under investigation, with the goal of evaluating the size and diversity of the electrotransformable soil community.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Characteristic(s) | Resistance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pLEPO1 | 7 kb, plastid (accD-rbcL) sequences flanking the aadA gene | 14 | |

| pBBR1MCS-3 | 5 kb, broad host range | Tcr | 13 |

| pBAB1 | pUC18 containing accD-rbcL genes | Apr | 14 |

| pBHC | 8.1 kb, pBBR1MC-S3 derivative containing accD-rbcL genes | Tcr | This study |

| pBHCRec | 9.7 kb, pBBR1MC-S3 derivative containing accD-rbcL genes | Tcr, Spr, Smr | This study |

| pGEMTeasy | Cloning vector | Apr | Promega |

Plasmid presence in the three isolated soil bacteria was confirmed by PCR with two sets of primers (415-416 and Chloro1-416). The presence of nonbacterial (plastid) sequences confirmed that the transformants were not members of native naturally antibiotic-resistant soil bacteria. The thermal cycling parameters used were 3 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of denaturation for 60 s at 94°C, annealing for 60 s at 55°C, and elongation for 60 s (70 s for Chloro1-Chloro2) at 72°C; and a final extension of 7 min at 72°C. The Chloro1-416 primer set was used to amplify part of the plastid and aadA genes (14). The 415-416 primer set was used to amplify the aadA gene.

Electrotransformation versus natural transformation.

Natural transformation requires a specific state of competence (18). To determine whether the isolated transformants were specifically obtained after electrotransformation instead of natural transformation, the isolates were tested for their natural transformability. The strains were first cured of the pBHCRec plasmid by subculturing without any selective pressure. The absence of the plasmid was confirmed by PCR (415-416 primer set). Ee2.1 could not be cured of the plasmid, so only strains Ee2.2 and N3 were used for all of the following transformation experiments. The pBHCRec-cured isolates were then harvested (40 μl) at different growth states, washed, and put in contact with the pBHC plasmid (570 ng) on a filter or on liquid medium for 1 night or 2 h of incubation, respectively. The pBHC plasmid (2,896-bp PvuII fragments from plasmid pBAB1 inserted into the SmaI site of plasmid pBBR1MCS-3) (Table 1) was used for the following electrotransformation experiments in order to be certain that the electrotransformants we were able to obtain did not correspond to siblings of uncured pBHCRec strains. No transformants were detected in the absence of electrical discharges (detection threshold of 10−9) at any of the tested growth phases (Fig. 1). The growth curves were also used to define the correlations between the bacterial densities and the optical densities; an optical density at 600 nm of 1 corresponded to 3.1 × 108 and 2.6 × 108 CFU/ml for strains N3 and Ee2.2, respectively.

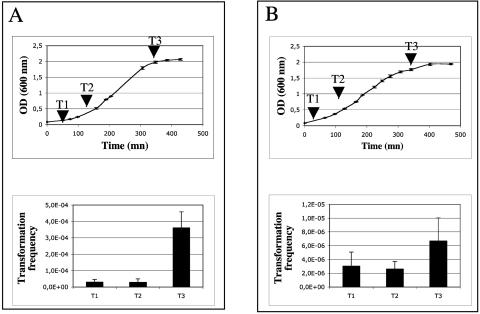

FIG. 1.

Effect of growth phase on electroporation-induced transformation frequencies of Pseudomonas sp. strains N3 (A) and Ee2.2 (B). The error bars represent the standard deviations. The electrotransformation frequencies are indicated for the sampling times (T1, T2, and T3).

Strain identification.

The electrotransformable isolates, Ee2.2 and N3, were then identified based on the 16S ribosomal DNA sequence. The rrn gene was amplified from total genomic DNA (DNeasy tissue kit; QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France) with PA-PH primers (4) and cloned into the pGEMTeasy plasmid (cloning kit; Promega, Madison, Wis.). Plasmids were isolated from E. coli DH5α with a Miniprep extraction kit (QIAGEN) and sent to Genome Express (Meylan, France) for sequencing. Database comparisons (BLAST; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) of the rrn genes of Ee2.2 (1,450 bp) and N3 (1,460 bp indicated 99% identity with the rrn gene of Pseudomonas jessenii strain PS06 and “Pseudomonas reactans,” respectively. “Pseudomonas reactans” is an unclassified bacterium considered to be saprophytic and mushroom associated (21a). Both strains belonged to the Pseudomonas genus but differed morphologically and genotypically (rrn genes had 97% identity). As Pseudomonas are considered fast growing, dominant soil bacteria and are often transformable (2), the experimental condition used might have favored them. However, Pseudomonas spp. are not necessarily the only electrotransformable bacteria present in soil, nor the most efficiently electrotransformed.

Electroporation frequencies.

The electrotransformation frequencies of Pseudomonas sp. strains N3 and Ee2.2 were compared to those of E. coli strain DH10B and P. fluorescens strain C7R12 (11). Before electroporation, cells (optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 to 0.7) were washed either once with sterile distilled water at room temperature or three times with 0.5 M sucrose at 4°C and then concentrated 100-fold. The sucrose method is considered the typical preparation method for electrocompetent cells (2). The pure bacterial suspension (40 μl) and the pBHC plasmid (570 ng) were introduced into chilled or nonchilled 0.2-cm-gap electroporation cuvettes (Equibio) and exposed to one pulse (Gene Pulser II; Bio-Rad) at 12.5 kV/cm, 200 Ω, and 25 μF. The frequencies of electrotransformation were determined as the number of tetracycline-resistant colonies divided by the number of recipient cells after incubation for 2 h at 28 or 37°C. All of the transformation frequencies reported in this article are the means of results from three independent experiments. Both of the isolated strains, Ee2.2 and N3, had electroporation frequencies on the order of magnitude of 10−4. Published transformation efficiencies for other Pseudomonas spp. generally resulted from experiments using optimal conditions. Results obtained with the isolated strains were consistent with those described in the literature (2), even though conditions were not optimized. The electrotransformation frequencies ranged from 10−2 to 10−3 when cells were treated with sucrose solution and a cold temperature before electrical discharge (Table 2). The laboratory strain, P. fluorescens C7R12, did not demonstrate significant electrotransformation frequencies (Table 2). This P. fluorescens strain could be transformed only if MgCl2 (10 mM) was introduced into the culture during the growth phase. The E. coli strain DH10B, washed with water, had an electroporation frequency comparable to those of isolated electrocompetent bacteria (Table 2). The electroporation efficiencies for the two isolated strains, Ee2.2 and N3, ranged between 103 and 105 CFU μg of DNA−1, depending on the electroporation conditions (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Electroporation and lightning-induced transformation frequencies of bacterial isolates and controls with the plasmid pBHCa

| Strain | Electrotransformation frequency

|

Lightning-induced transformation frequencyb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without sucrose (22°C) | With 0.5 M sucrose (4°C) | Experiment 1 (20°C) | Experiment 2 (20°C) | |

| Pseudomonas sp. strain Ee2.2 | 4.9 × 10−4 (1.7 × 10−4) | 2.7 × 10−3 (1.5 × 10−3) | 1.2 × 10−5 | 5.3 × 10−7 (2.8 × 10−7) |

| Pseudomonas sp. strain N3 | 2.7 × 10−4 (2.2 × 10−4) | 1.9 × 10−2 (1.1 × 10−3) | 5.3 × 10−4 (2.8 × 10−4) | 7.2 × 10−6 |

| E. coli DH10B | 3.6 × 10−4 (2.7 × 10−4) | 1.4 × 10−6 (8.5 × 10−7) | <10−9 | ND |

| P. fluorescens C7R12 | <10−8 | 10−7c | <10−9 | ND |

Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. ND, not determined.

There were 5 months between experiments 1 and 2.

MgCl2 (10 mM) was required.

TABLE 3.

Transformation efficiencies of bacterial strains subjected to electroporationa

| Strain | Transformation efficiency (CFU/μg of plasmid DNA)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Without sucrose (22°C) | With 0.5 M sucrose (4°C) | |

| Pseudomonas sp. strain Ee2.2 | 4.9 × 103 (1.9 × 103) | 4.1 × 104 (2.3 × 104) |

| Pseudomonas sp. strain N3 | 1.3 × 104 (1.4 × 103) | 5 × 105 (1.1 × 105) |

| E. coli DH10B | 2.6 × 104 | 4 × 103 |

| P. fluorescens C7R12 | ND | ND |

Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. ND, not determined.

Lightning-induced transformation frequencies in sterile soil.

Pure cultures of strains Ee2.2, N3, DH10B, and C7R12 were added to sterile soil and subjected to laboratory-scale lightning. E. coli strain DH10B was used as the positive control (8), and P. fluorescens C7R12 was used as the Pseudomonas reference strain. The soil experimental system used (soil from Côte Saint-André, France) was the same as that previously described (8). The soil was dried before γ-sterilization (25-kGy; IONISOS, Dagneux, France). The day before the lightning current injection, the soil (35 g) was hydrated with distilled water to between 13 and 15% (wt/wt) humidity. The water-holding capacity of this soil is around 28%. The working humidity was dependent on the electrical parameters required. A drier soil led to lightning breakdown, and a more humid soil led to a decrease in electrical tension. A 50-mm-diameter petri dish containing a round disk of aluminum foil at the bottom (electrode) was filled with the soil. The cell preparation and plasmid quantities were identical to those used for electroporation. The bacteria-DNA mixture was then deposited onto the surface of the soil. Approximately 108 cells harvested at the exponential phase were mixed with the pBHC plasmid. The second electrode was then placed on the surface of the soil to permit current injection. The microcosms were subject to electrical tensions ranging from 5 to 5.6 kV/cm. In nature, the lightning flash and thunder are due to the flow of high electrical currents into an ionized channel which connects the ground to the cloud. At ground level, these currents penetrate the soil through a small surface (a few square centimeters) and spread more or less uniformly, depending on the soil homogeneity. The flow of current in the soil creates an electric field which is applied to the living material. Very near the impact point of the lightning, the strains may be destroyed, but as the current density decreases with the distance from this point, there is a wide area where the electric field is in a good range to favor electrotransformation (a few kilovolts per centimeter) (8).

Around 2 g of inoculated soil was then placed into 100 ml of Luria-Bertani medium and incubated for 2 h at 28 or 37°C. Negative controls corresponded to the cell-DNA mixture without electrical discharge. The first objective was to determine if the isolated soil bacterial strains would be transformed when subjected to lightning. Transformation of all of the strains by the pBHC plasmid was detected after overnight incubation and confirmed by PCR (Chloro1-Chloro2 primer set). The lightning transformation frequencies of all of the strains after 2 h of incubation were then compared to the electroporation frequencies (Table 2). The N3 and Ee2.2 lightning electrotransformants were detected at 10−4 and 10−5 frequencies, respectively (Table 2, experiment 1). The electroporation and lightning transformation frequencies with the pBHC plasmid differed by about 1 log for strains N3 and Ee2.2. The strong correlation between electroporation and lightning frequencies observed for the isolated strains suggests that the electroporation transformation frequencies observed in vitro have some ecological significance. The lightning-induced transformation frequencies, which ranged from 10−4 to 10−5 with an 8-kb plasmid in soil, could be extrapolated to transform at least 10 and up to 100 Pseudomonas spp. bacteria per gram of soil per lightning strike. Natural transformation frequencies ranged from 10−8 to 10−9 with P. fluorescens and Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains under equivalent conditions in terms of plasmid size, DNA concentration, and cell density (9). Moreover, many frequencies of natural transformation are measured by using complex high-nutrition growth media, supplemented soil extract, or nutriment-amended soil (18). Electrotransformation frequencies reported here were measured directly in soil. The isolation of “lightning-competent” bacterial strains, their lightning-induced transformation frequencies, and the accessibility of diverse sources (extracellular, living, and dying) of DNA in soil (18, 23) could increase our understanding of the importance of lightning-induced gene transfer for bacterial adaptation and evolution. The influence of electrical, DNA, and soil parameters on the ecological significance of lightning transformation is under investigation. The control bacteria, E. coli strain DH10B and P. fluorescens C7R12, did not exhibit a measurable lightning-induced transformation frequency (<10−9) with the incubation period of 2 h. Lightning-induced transformation can probably be extended to a number of bacteria. However, the frequencies described in this study do not seem to be a universal characteristic of Pseudomonas since P. fluorescens strain C7R12 behaved differently from Pseudomonas strains Ee2.2 and N3. In experiment 2, 3.8 × 103 and 5.9 × 104 transformants μg of DNA−1 were counted in lightning-hit soil for strains Ee2.2 and N3, respectively.

Effect of growth phase on electrotransformability.

Frequencies of electrotransformation in the presence of the pBHC plasmid were tested at different growth phases (lag, exponential, and stationary). Pseudomonas sp. strain N3 had the highest electrotransformation frequency in the stationary phase (Fig. 1A), while the physiological state for strain Ee2.2 had no apparent effect on its electrotransformability (Fig. 1B). The important difference in transformation requirements between lightning transformation and natural transformation resides in the bacterial state of transformability. While a specific state of competence is required for naturally competent bacteria (18), the lightning-competent isolates have been transformed during all of their growth phases both in vitro and in situ (data not shown).

The approach described in the present study has shown that the bacterial community directly isolated from soil by Nycodenz extraction constituted an effective pool of bacteria for finding examples of those that were lightning competent. Direct Nycodenz extraction might have avoided significant modifications of microbial diversity and cell physiology linked to a cultivation step (6). While Nycodenz extraction of soil bacteria has been used extensively for genomic and diversity studies (25), only recently have the Nycodenz-extracted bacteria been considered a pool of physiologically active soil bacteria (24, 28).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences of the rrn genes of Ee2.2 and N3 have been deposited under accession numbers AY625608 and AY625609, respectively.

Acknowledgments

The European Community funded this research through the fifth RTD program, “Quality of life and management of living resources,” project TRANSBAC QLK3-CT-2001-02242. This work was also part of the project “Développement et exploitation de librairies d'ADN métagénomique,” funded by the Région Rhône-Alpes (Thématiques Prioritaires, Sciences Analytiques Appliquées).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakken, L. R., and V. Lindahl. 1995. Recovery of bacterial cells from soil, p. 9-27. In J. D. Van Elsas and J. T. Trevors (ed.), Nucleic acids in the environment: methods and applications. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

- 2.Bassett, C. L., and W. J. Janisiewicz. 2003. Electroporation and stable maintenance of plasmid in a biocontrol strain of Pseudomonas syringae. Biotechnol. Lett. 25:199-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer, B., K. Hanselmann, W. Schlimme, and B. Jenni. 1996. Genetic transformation in freshwater: Escherichia coli is able to develop natural competence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3673-3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce, K. D., W. D. Hiorns, J. L. Hobman, A. M. Osborn, P. Strike, and D. A. Ritchie. 1992. Amplification of DNA from native populations of soil bacteria by using the polymerase chain reaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3413-3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claverys, J. P., and B. Martin. 2003. Bacterial competence genes: signatures of active transformation, or only remnants? Trends Microbiol. 11:161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courtois, S., A. Frostegard, P. Gorensson, G. Depret, P. Jannin, and P. Simonet. 2001. Quantification of bacterial subgroups in soil: comparison of DNA extracted directly from soil or from cells previously released by density gradient centrifugation. Environ. Microbiol. 3:431-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davison, J. 1999. Genetic exchange between bacteria in the environment. Plasmid 42:73-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demanèche, S., F. Bertolla, F. Buret, R. Nalin, A. Sailland, P. Auriol, T. M. Vogel, and P. Simonet. 2001. Laboratory-scale evidence for lightning-mediated gene transfer in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3440-3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demanèche, S., E. Kay, F. Gourbière, and P. Simonet. 2001. Natural transformation of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Agrobacterium tumefaciens in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2617-2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drury, L. 1996. Transformation of bacteria by electroporation, p. 249-256. In A. J. Harwood (ed.), Basic DNA and RNA protocols. Methods in molecular biology, vol. 58. Humana Press, Inc., Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eparvier, A., P. Lemanceau, and C. Alabouvette. 1991. Population dynamics of non-pathogenic Fusarium and fluorescent Pseudomonas strains in rockwool, a substratum for soilless culture. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 86:177-184. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katayama, A., K. Kai, and K. Fujie. 1998. Extraction efficiency, size distribution, colony formation and [3H]-thymidine incorporation of bacteria directly extracted from soil. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 44:245-252. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay, E., T. M. Vogel, F. Bertolla, R. Nalin, and P. Simonet. 2002. In situ transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from transgenic (transplastomic) tobacco plants to bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3345-3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindahl, V. 1996. Improved soil dispersion procedures for total bacteria counts, extraction of indigenous bacteria and cell survival. J. Microbiol. Methods 25:279-286. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindahl, V., and D. R. Bakken. 1995. Evaluation of methods for extraction of bacteria from soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 16:135-142. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenz, M. G. 1998. Horizontal gene transfer among bacteria in soil by natural genetic transformation, p. 19-43. In N. S. Subba Rao and Y. R. Dommergues (ed.), Microbial interactions in agriculture and forestry, vol. I. Science Publishers, Inc., Lebanon, N.H. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorenz, M. G., and W. Wackernagel. 1994. Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment. Microbiol. Rev. 58:563-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lurquin, P. F. 1997. Gene transfer by electroporation. Mol. Biotechnol. 7:5-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maniatis, T. E., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 21.Mayr, C., A. Winding, and N. B. Hendriksen. 1999. Community level physiological profile of soil bacteria unaffected by extraction method. J. Microbiol. Methods 36:29-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Munsch, P., V. A. Geoffroy, T. Alatossava, and J.-M. Meyer. 2000. Application of siderotyping for characterization of Pseudomonas tolaasii and “Pseudomonas reactans” isolates associated with brown blotch disease of cultivated mushrooms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4834-4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newell, C. A. 2000. Plant transformation technology. Developments and applications. Mol. Biotechnol. 16:53-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen, K. M., K. Smalla, and J. D. van Elsas. 2000. Natural transformation of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 with cell lysates of Acinetobacter sp., Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Burkolderia cepacia in soil microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:206-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prieme, A., J. I. B. Sitaula, A. K. Klemedtsson, and L. R. Bakken. 1996. Extraction of methane-oxidizing bacteria from soil particles. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 21:59-68. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robe, P., R. Nalin, C. Capellano, T. M. Vogel, and P. Simonet. 2003. Extraction of DNA from soil. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 39:183-190. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz-Diez, B. 2002. Strategies for the transformation of filamentous fungi. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saunders, N. J., D. W. Hood, and E. R. Moxon. 1999. Bacterial evolution: bacteria play pass the gene. Curr. Biol. 9:R180-R183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitley, A. S., R. I. Griffiths, and M. J. Bailey. 2003. Analysis of the microbial functional diversity within water-stressed soil communities by flow cytometric analysis and CTC+ cell sorting. J. Microbiol. Methods 54:257-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]