Abstract

Formation of oil-water emulsions during bacterial growth on hydrocarbons is often attributed to biosurfactants. Here we report the ability of certain intact bacterial cells to stabilize oil-in-water and water-in-oil emulsions without changing the interfacial tension, by inhibition of droplet coalescence as observed in emulsion stabilization by solid particles like silica.

Emulsions are commonly observed when liquid hydrocarbons and water are mixed during bioremediation or fermentation (2). These emulsions dramatically increase the area of the oil-water interface, thereby enhancing bioavailability. For a dispersion of one liquid in another to be stable enough to be classified as an emulsion, a third component, such as a surfactant, must be present to stabilize the system. Fine solid particles such as silica beads can also stabilize emulsions if they attach at the interface between the oil and the water to prevent droplets from coalescing (4, 14, 23). While bacteria can produce surfactants or emulsifiers that stabilize emulsions (1, 5, 18), some microorganisms can emulsify hydrocarbons even in the absence of cell growth or uptake of hydrocarbons (18). The latter observation suggests that emulsification may be associated with the surface properties of the cells, as a result of attachment to the oil-water interface by general hydrophobic interactions rather than specific recognition of the substrate (5, 21). Bacterial cells may, therefore, behave as fine solid particles at interfaces.

Given that fine solid particles can stabilize oil-water emulsions, our hypothesis was that intact, stationary-phase bacteria can stabilize oil-water emulsions by adhering to the oil-water interface and that this property is related to cell surface hydrophobicity. We selected four hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial species and determined the surface properties of washed stationary-phase cells by cell adhesion to hydrocarbons, the contact angle, and the interfacial tension. The structure of the emulsions was observed by confocal microscopy, and the behavior of oil droplets in bacterial suspensions was measured with a micropipette apparatus. These results were used to make general inferences about the ability of intact, bacterial cells to stabilize oil-water emulsions.

The n-alkane-degrading bacteria employed in this study were Acinetobacter venetianus RAG-1 (16, 20), Rhodococcus erythropolis 20S-E1-c (9), and Rhizomonas suberifaciens EB2-1a (8). Pseudomonas fluorescens LP6a degrades a range of aromatic hydrocarbons but not n-alkanes (8). All bacterial cultures were grown in Trypticase soy broth (Difco, Sparks, Md.) with incubation at 28°C and gyratory shaking. Each culture was harvested at its stationary phase by centrifugation and washed twice with 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7).

The harvested and washed cells were used to characterize the cell surface properties. Bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbons (BATH) was measured as described by Rosenberg et al. (17). Cells were resuspended in phosphate buffer to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of about 0.6. An aliquot of cell suspension (1.2 ml) was mixed with 1 ml of n-hexadecane (99% pure; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) by vortexing for 120 s and allowed to separate for 15 min. The OD600 of the aqueous phase was then measured spectrophotometrically. The difference between the optical density of the aqueous phase before and after mixing with n-hexadecane was used to calculate the adhesion as a percentage: 100 × [1 − (OD600 after mixing/OD600 before mixing)].

Contact angle was measured using a modified protocol from the work of Neufeld et al. (13). A lawn of bacterial cells was prepared by filtering the washed cell suspensions through a 0.22-μm-pore-size polyvinylidene difluoride membrane filter (Millipore, Fisher Scientific Ltd., Nepean, Ontario) and then dried at room temperature for 24 h in a biosafety cabinet. The filter was immersed in n-hexadecane, and a 20-μl droplet of distilled water was placed on the cell lawn. The three-phase contact angle between the aqueous drop, bacterial lawn, and hexadecane was measured using a microscope with a goniometric eyepiece (DSA10; Krüss USA, Charlotte, N.C.).

Emulsions were prepared by suspending the twice-washed cells in 10 ml of phosphate buffer to give a concentration of 5 kg (dry weight) m−3 and then mixed with 40 ml of n-hexadecane in 20-mm diameter test tubes for 5 min at high speed on a vortex mixer. The mixtures were then poured into graduated cylinders and allowed to separate for 24 h. The volumes of stable emulsion were calculated as a percentage of the total initial volume. As a control to determine if the cells released extracellular material during this treatment, cell suspensions were mixed by vortexing, the cells were removed by centrifugation, and the cell-free supernatant was tested for emulsion-stabilizing properties as described above. The emulsion structure (i.e., oil-in-water or water-in-oil) was examined under a confocal microscope (Leica TCS-SP2 Multiphoton confocal laser scanning microscope), with the addition of sodium fluorescein (0.1%) solution to stain the cells prior to mixing with n-hexadecane.

The micropipette technique was used to measure the interfacial tension between water and n-hexadecane in the presence of bacterial cells (24). Glass micropipettes with 10- to 15-μm tip diameters were made from glass capillary tubes (1-mm outside diameter, 0.7-mm inside diameter; Kimble Glass Inc., Vineland, N.J.) (12). The sample was observed by using an inverted microscope (Axiovert 100; Carl Zeiss, North York, Canada), and the micropipettes were controlled with hydraulic micromanipulators (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Pressure in the pipettes was controlled by a syringe connected through flexible tubing and measured by a pressure transducer (Omega Engineering, Stamford, Conn.). The micropipette tip was filled with n-hexadecane and then placed in a small volume of cell suspension (or water or phosphate buffer as a control). The pressure required to push the oil droplet out of the micropipette gave a measurement of interfacial tension.

Correlation of BATH tests and contact angle.

The BATH test results presented in Table 1 demonstrate a wide range of cell adhesion to n-hexadecane, from 18.3% for P. fluorescens LP6a to 95.7% for A. venetianus RAG-1. P. fluorescens LP6a showed almost no affinity for n-hexadecane, because the hydrocarbon droplets rose and coalesced soon after mixing. In contrast, A. venetianus RAG-1, which is known to adhere avidly to n-hexadecane (17), formed stable, long-lasting emulsions.

TABLE 1.

Emulsion and surface properties of the four bacterial strains and cell-free control preparationsa

| Bacterial strain or control | Bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbon (%; n = 3) | Three-phase contact angle (°, n = 5) | Interfacial tension (mN m−1)

|

Emulsion vol (%; n = 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial (n = 5) | Equilibrated (n = 5) | ||||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens LP6a | 18.3 ± 4.2 | 39.7 ± 4.8 | 46.0 ± 1.0 | NAb | 0 |

| Rhizomonas suberifaciens EB2-1a | 55.0 ± 2.4 | 50.3 ± 3.8 | 46.3 ± 1.0 | 36.1 ± 1.3 | 2 ± 1 |

| Rhodococcus erythropolis 20S-E1-c | 80.3 ± 1.5 | 152.9 ± 1.3 | 46.0 ± 1.5 | 33.6 ± 1.1 | 22 ± 1 |

| Acinetobacter venetianus RAG-1 | 95.7 ± 1.8 | 56.4 ± 2.4 | 46.1 ± 1.1 | 36.3 ± 1.1 | 80 ± 2 |

| Cell-free control | 0 | 143.0 ± 2.0 | 46.5 ± 2.1 | NA | 0 |

Values are means ± standard deviations.

NA, not applicable; droplets of n-hexadecane were not stable in suspensions of P. fluorescens LP6a or in buffer.

The data in Table 1 show three-phase contact angles ranging from 40 to 153°. A similar range of contact angles was observed by van der Mei (19) for A. venetianus, depending on the growth medium. As a control, contact angle was measured on filter paper in the absence of cells. The result of this measurement (Table 1) indicated a surface that was highly hydrophobic but slightly less hydrophobic than that of the most hydrophobic bacterium, R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c.

Interfacial tension and inhibition of droplet coalescence.

In the absence of suspended cells, the interfacial tension was 48.7 ± 2.1 mN m−1 for a droplet of n-hexadecane extruded into pure water and 46.5 ± 2.1 mN m−1 for phosphate buffer-hexadecane (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3), in agreement with published values (10). When the interfacial tension was measured immediately after n-hexadecane and hydrophobic bacterial strains had been brought into contact, no decrease was observed and the measured values were equivalent to those with the phosphate buffer and hexadecane. Equilibrium measurements, taken after cells had been allowed to assemble at the water-oil interface for 5 min, were only slightly lower, indicating that none of the cell suspensions significantly affected the interfacial tension.

In order to test the mechanism of emulsion stabilization by bacteria, two hexadecane droplets stabilized by hydrophobic bacteria were pushed together. Despite attempts to induce coalescence through forced contact for up to several minutes, the droplets remained separate entities (Fig. 1A). To further demonstrate that the bacteria at the interface interact with each other to form a surface film, we extruded a hexadecane droplet into individual suspensions of A. venetianus RAG-1 and R. erythropolis 20S-E-1c and then after a few minutes slowly withdrew the droplet, reducing the interfacial area. Micrographs (Fig. 1B and C) clearly show a rigid film at the hydrocarbon-water interface due to the presence of bacteria that resisted the change in surface area to form a crumpled surface. Figure 1B was recorded after partial withdrawal of the oil droplet, while Fig. 1C was recorded after complete droplet withdrawal. The same phenomena have been observed with hydrophobic clay particles and silica beads at an oil-water interface (6, 11). When the same experiment was repeated with the hydrophilic P. fluorescens LP6a, no such distortion of the droplet surface was observed and the deflating droplet remained spherical as it shrank.

FIG. 1.

Behavior of oil droplets in water with bacteria. (A) Two droplets of n-hexadecane extruded into an aqueous suspension of A. venetianus RAG-1. The droplets were stabilized against coalescence by bacteria at the oil-water interface (the pipette tip has a diameter of 14 μm). (B) Deformation of the oil-water interface after partial withdrawal of n-hexadecane droplet caused by R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c adhering tightly at the interface when the hexadecane droplet is extruded into the cell suspension, equilibrated, and then withdrawn. (C) Appearance after complete withdrawal of n-hexadecane droplet.

Emulsions stabilized by bacteria.

After the oil-bacterium suspensions were emulsified and allowed to stand for 24 h, the emulsified layer ranged from 0 to 80% (vol/vol), reported as a fraction of the mixture's total volume (oil plus water). A. venetianus RAG-1 yielded the largest volume of emulsion, which was stable for up to several months, whereas the smaller amount of emulsion formed by R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c was less stable and over 24 h decreased by 30% from the initial volume (Table 1). In contrast, P. fluorescens LP6a and Rhizomonas suberifaciens EB2-1a did not yield stable emulsions. In control experiments, the removal of the cells after vortexing to give cell-free supernatants resulted in no formation of emulsions, showing that stationary-phase cells of A. venetianus RAG-1 and R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c were required for the formation and stabilization of emulsions and that any biosurfactants or bioemulsifiers were insignificant.

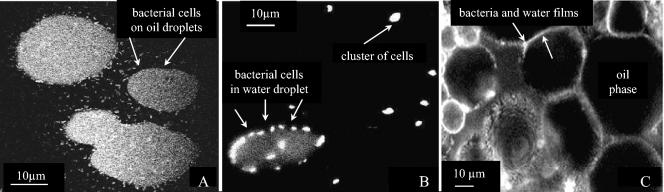

Emulsion microscopy.

After gravity separation in a graduated cylinder, emulsions prepared with R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c formed distinct layers. Staining of the cells with fluorescein showed that the middle layer (i.e., the stable emulsion) comprised an oil-in-water emulsion (Fig. 2A), while the oily phase (top layer) revealed water-in-oil emulsions featuring assemblies of cells surrounded by thin water films (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Emulsions stabilized by bacteria. (A) Confocal micrograph of an oil-in-water emulsion formed by R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c, with fluorescent bacteria surrounding hexadecane droplets. (B) Confocal micrograph of a water-in-oil emulsion formed by R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c. Clusters of bacteria surrounded by a thin film of water can be seen at the right. (C) Confocal micrograph of the “emulsion gel” formed by mixing an A. venetianus RAG-1 suspensions with n-hexadecane. Fluorescent bacteria are seen in the thin films surrounding the larger (dark) hexadecane drops.

The stable emulsion formed by A. venetianus RAG-1 represented 80% of the total volume. Confocal microscopy revealed an unexpected structure of dark oil droplets surrounded by bacterial films connected in a three-dimensional network (Fig. 2C). The emulsion contained a high volume fraction of oil and did not flow in the sample tube unless shaken, indicating a yield stress like that of an emulsion gel (3).

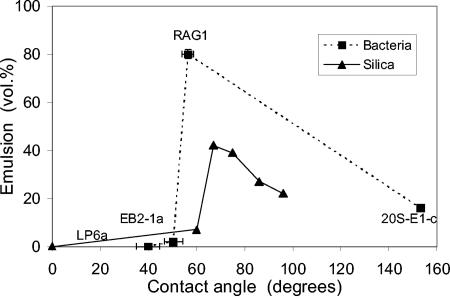

Relation of emulsification to bacterial hydrophobicity.

The volume of emulsion increased monotonically with cell adherence to n-hexadecane (Table 1), but the relationship was highly nonlinear. An increase in adhesion from 80.3% for R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c to 95.7% for A. venetianus RAG-1 increased the volume of emulsion from 22 to 80%. When the stable emulsion volume was plotted against the three-phase contact angle (Fig. 3), a maximum was observed for A. venetianus RAG-1, which had an intermediate contact angle, followed by a decrease in emulsion volume for R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c which had the largest contact angle. The lowest-contact-angle bacterium, P. fluorescens LP6a, formed no stable emulsion, and all the cells partitioned into the water phase. The same pattern of behavior was observed for fine silica spheres (diameter, 12 nm) with a range of contact angles (23). Hydrophobic silica remained in the water, while highly hydrophobic particles (contact angle > 65°) increasingly entered the oil phase. The reduction in the volume of emulsion with increasing contact angle for R. erythropolis 20S-E1-c, past the optimum value of 55 to 65°, was due to migration of cells into the oil phase. The other bacteria did not enter the oil phase, because the oil was clear after 24 h of settling. The maximum volume of emulsion would be formed when all of the cells, or particles, were at the interface rather than in the water phase (contact angle approaching 0°) or the oil phase (contact angle approaching 180o)

FIG. 3.

Comparison between emulsion volume and contact angle for the four bacterial strains and silica particles having a range of hydrophobicity. The full names of the strains are given in Table 1. Data for silica particles are from the work of Yan et al. (23).

Significance of observations.

This study showed that intact, washed bacteria alone could stabilize oil-water emulsions by attaching to the interface, analogous to silica particles with contact angles intermediate between water-wet and oil-wet. The attached bacteria hindered the coalescence of oil droplets (Fig. 1A) and interacted to form surface films (Figs. 1B, 2A, and 2B) and emulsion gels (Fig. 2C). The same mechanism of steric hindrance of coalescence was responsible for stabilization of emulsions by silica particles (23). In addition, the high interfacial tension values recorded during the micropipette experiments showed that cells stabilized emulsions without significantly changing the interfacial tension, consistent with the behavior of fine particles (11) rather than surfactants.

The observed ability of different bacterial species to form emulsions was in qualitative agreement with their contact angles and followed the same pattern as silica particles (Fig. 3). While hydrophobic cells stabilized oil-water emulsions for a long time, hydrophilic bacteria showed no adherence to oil droplets and were not able to stabilize emulsions. Consequently, the most stable emulsions were formed by bacteria with intermediate hydrophobicity, which is in accordance with the findings regarding solid particles (23). The emulsion types observed, from oil-in-water emulsions with bacteria displaying intermediate contact angles to water-in-oil emulsions with bacteria having high contact angles, were the same as those observed for silica particles over the same range of contact angles (23). Even though R. erythropolis 20SE1-c showed strong adherence to oil droplets, the migration of some of the cells into the oil phase made this emulsion less stable and reduced the volume of emulsion. Previous studies have commented on passage of hydrophobic cells into the hydrocarbon phase during growth (15, 22), and microbes have been recovered from hydrocarbon fuels that were essentially free of water (7).

In addition to strong adhesion to the oil-water interface, hydrophobic bacteria possess an affinity for each other, leading to the self-assembly of bacteria at the oil-water interface, which resists coalescence and deformation. The observation of self-assembly of bacteria at the oil-water interface, namely, the surface skin that resists deformation (Fig. 1B and C), was apparent for both A. venetianus RAG-1 and R. erythropolis 20SE1-c during the micropipette experiment. The combination of strong cell-cell interactions and the strong adherence between the cells and oil droplets was likely responsible for the emulsion gel structure observed for A. venetianus RAG-1 (Fig. 2C). Emulsion gels are usually obtained via multiple emulsions, such as oil droplets inside water droplets in oil, which form during mechanical agitation of a less stable emulsion that breaks to form a more stable emulsion. When such an emulsion is subjected to small shear deformation, it usually exhibits a yield stress, because the surface tension opposes the deformation of the oil droplets (4).

Our results suggest that bacterial cells can play a role in stabilizing emulsions in circumstances ranging from oil spills to fermentation. The observed self-assembly of bacteria at the interface to form a surface skin that resists deformation may be important for fluid flow through porous media, as in petroleum production and bioremediation of aquifers contaminated by nonaqueous-phase liquids.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada for financial support.

We thank Vincente Munoz, CANMET-AST, for assistance with confocal microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, P. G., D. S. Francy, K. L. Duston, J. M. Thomas, and C. H. Ward. 1992. Biosurfactant production and emulsification capacity of subsurface microorganisms, p. 58-66. In Preprints “Soil decontamination using biological processes.” Dechema, Karlsruhe, Germany.

- 2.Atlas, R. M., and R. Bartha. 1992. Hydrocarbon degradation and oil-spill bioremediation. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 12:287-338. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babak, V. G., and M. J. Stébé. 2002. Highly concentrated emulsions: physicochemical principles of formulation. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 23:1-22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briggs, T. R. 1921. Emulsions with finely divided solids. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 13:1008-1010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper, D. G., J. Akit, and N. Kosaric. 1982. Surface activity of the cells and extracellular lipids of Corynebacterium fascians CF15. J. Ferment. Technol. 60:19-24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dabros, T., A. Yeung, J. Masliyah, and J. Czarnecki. 1999. Emulsification through area contraction. J. Coll. Int. Sci. 210:222-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeGray, R. J., and L. N. Killian. 1962. Life in essentially non aqueous hydrocarbons. Dev. Ind. Microbiol. 3:296-303. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foght, J. M., K. Semple, D. W. S. Westlake, S. Blenkinsopp, G. Sergy, Z. Wang, and M. Fingas. 1998. Development of a standard bacterial consortium for laboratory efficacy testing of commercial freshwater oil spill bioremediation agents. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 21:322-330. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foght, J. M. 1999. Identification of the bacterial isolates comprising the environment Canada freshwater and cold marine standard inocula, using 16S rRNA gene sequencing and analysis. Manuscript report EE-164. Environmental Protection Service, Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

- 10.Lee, S., D. H. Kim, and D. Needham. 2001. Equilibrium and dynamic interfacial tension measurements at microscopic interfaces using a micropipet technique. 1. A new method for determination of interfacial tension. Langmuir 17:5537-5543. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine, S., B. D. Bowen, and S. J. Partridge. 1989. Stabilization of emulsions by fine particles. I. Partitioning of particles between continuous phase and oil/water interface. Colloids Surfaces 38:325-343. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moran, K., A. Yeung, and J. Masliyah. 1999. Measuring interfacial tensions of micrometer-sized droplets: a novel micromechanical technique. Langmuir 15:8497-8504. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neufeld, R. J., J. E. Zajic, and D. F. Gerson. 1980. Cell surface measurements in hydrocarbon and carbohydrate fermentations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 39:511-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickering, S. U. 1907. Emulsions. J. Chem. Soc. 91:2001-2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed, G. B., and C. E. Rice. 1931. The behavior of acid-fast bacteria in oil and water systems. J. Bacteriol. 22:239-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reisfeld, A., E. Rosenberg, and D. Gutnick. 1972. Microbial degradation of crude oil: factors affecting the dispersion in sea water by mixed and pure cultures. Appl. Microbiol. 24:363-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg, M., D. Gutnick, and E. Rosenberg. 1980. Adherence of bacteria to hydrocarbons: a simple method for measuring cell-surface hydrophobicity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 9:29-33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg, M., and E. Rosenberg. 1985. Bacterial adherence at the hydrocarbon-water interface. Oil Petrochem. Pollut. 2:155-162. [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Mei, H. C., M. M. Cowan, and H. J. Busscher. 1991. Physicochemical and structural studies on Acinetobacter calcoaceticus RAG-1 and MR-481—two standard strains in hydrophobicity tests. Curr. Microbiol. 23:337-441. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaneechoutte, M., I. Tjernberg, F. Baldi, M. Pepi, R. Fani, E. R. Sullivan, J. van der Toorn, and L. Dijkshoorn. 1999. Oil-degrading Acinetobacter strain RAG-1 and strains described as ‘Acinetobacter venetianus sp. nov.' belong to the same genomic species. Res. Microbiol. 150:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. 1987. The role of bacterial cell wall hydrophobicity in adhesion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:1893-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watkinson, R. J., and P. Morgan. 1990. Physiology of aliphatic hydrocarbon-degrading microorganisms. Biodegradation 1:79-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan, N., M. R. Gray, and J. H. Masliyah. 2001. On water-in-oil emulsions stabilized by fine solids. Colloids Surfaces A 193:97-107. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeung, A., T. Dabros, J. Masliyah, and J. Czarnecki. 2000. Micropipette: a new technique in emulsion research. Colloids Surfaces A 174:169-181. [Google Scholar]