Abstract

Viruses are abundant in all known ecosystems. In the present study, we tested the possibility that viruses from one biome can successfully propagate in another. Viral concentrates were prepared from different near-shore marine sites, lake water, marine sediments, and soil. The concentrates were added to microcosms containing dissolved organic matter as a food source (after filtration to allow 100-kDa particles to pass through) and a 3% (vol/vol) microbial inoculum from a marine water sample (after filtration through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter). Virus-like particle abundances were then monitored using direct counting. Viral populations from lake water, marine sediments, and soil were able to replicate when they were incubated with the marine microbes, showing that viruses can move between different ecosystems and propagate. These results imply that viruses can laterally transfer DNA between microbes in different biomes.

In all known ecosystems, viruses are very abundant. There are approximately 107 virus-like particles (VLPs) per ml of surface seawater (2; reviewed in references 17 and 52), up to 108 VLPs per g of marine sediment (11, 12), ∼108 VLPs per g of soil (50), and 105 to 109 VLPs per ml of freshwater (9, 27, 46). VLPs are also common in extreme environments, including hot springs (105 to 109 VLPs per ml [7]), hypersaline lakes (106 to 109 VLPs per ml [15, 25, 32]), and solar salterns (up to 1010 per ml [20, 35, 36]). Because bacteria are the most common potential prey for viruses, most of the environmental VLPs are assumed to be phages. Direct evidence for this supposition has been obtained by transmission electron microscopy (1-3, 14, 21, 38, 45, 48) and metagenomic analyses (4, 6).

Phages play an important role in global carbon cycling by lysing marine heterotrophic and autotrophic prokaryotic hosts (reviewed in references 17 and 52). Phages are also responsible for enhancing lateral gene transfer among prokaryotes (10, 26, 34). Approximately 1014 transductant events occur per year in Tampa Bay Estuary, Florida (26), and Paul et al. (33) estimated that 1028 bp of DNA are transduced by phages every year in the world's oceans.

In coastal surface seawater, most phages are produced though lytic infections (49). This means that phages must find new hosts in a timely fashion because the half-life of a free viral particle is only about 36 h (reviewed in reference 52). Wilcox and Fuhrman (49) showed that marine bacteria can escape their phage predators if the frequency of infection is reduced by dilution into phage-free seawater. In the present study, the experimental approach of Wilcox and Fuhrman was used to test the hypothesis that nonmarine phages can prey upon marine microbes. We show that viruses from soil, sediment, and freshwater can infect and propagate on marine microbial communities. These results imply that viruses can contribute to global lateral gene transfer by moving DNA between biomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of environmental samples.

Twenty-liter water samples were collected in carboys in shallow, near-shore locations. Surface sediment and soil samples (∼4 kg) were collected using Tri-pour beakers and placed in Ziploc bags. All samples were stored at 4°C until they could be processed. The water samples were collected from the San Diego, Calif., area, including Pacific Beach (29 April 2003), Ocean Beach (OB; 17 June and 23 September 2003), Silver Strand Beach (27 July 2003), Mission Bay (MB; 23 March, 29 April, 27 July, and 29 September 2003), La Jolla Cove (LJ Cove; 29 April and 5 August 2003), and Lake Murray (LM; 27 July and 23 September 2003). Sediment samples were taken from MB (27 July 2003) and OB (23 September 2003). The soil sample was collected from LM Park (23 September 2003). All samples used for making the viral concentrates were processed within 7 days. Samples collected for the microbial (MICR) (filter pore size, 0.45 μm) inocula and dissolved organic matter (DOM) (filter pore size allowing particles of 100 kDa to pass through) fractions were processed on the day of collection (Fig. 1).

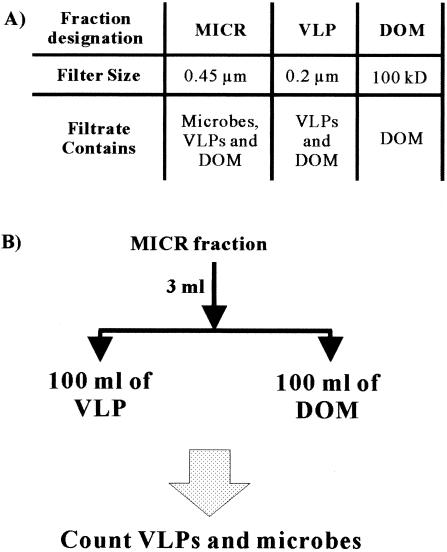

FIG. 1.

Filtrates (A) and basic experimental protocol (B) used in this paper. In the mixing experiments (e.g., Fig. 3), the basic experimental procedure was modified by adding 1 ml of a 100× viral concentrate to 100 ml of the DOM fraction in place of the VLP fraction.

Filtration fractions.

The different filtrates used in these experiments are outlined in Fig. 1A. A vacuum pump was used to filter samples through a GF/F filter (Whatman; nominal pore size, 0.45 μm) to obtain the MICR fraction (0.45-μm filtrate), which was used as the inoculum. The 0.45-μm filtrates contained bacteria, viruses, and DOM but not protists. Each sample was passed through the 0.45-μm-pore-size filter twice to ensure that all protists were removed (49). In tangential-flow filtrations (TFFs; Amersham Biosciences), we used filters with pore sizes that allowed the passage of particles with diameters of 0.2 μm and masses of 100 kDa to obtain VLP and DOM fractions, respectively. The 0.2-μm TFF removes bacteria but allows viruses and DOM to pass through. The 100-kDa TFF removes viruses, and its filtrate contains only DOM. For the soil and sediment samples, ∼3 kg of the sample was resuspended in 10 liters of seawater that had been filtered to allow 100-kDa particles to pass through and then was passed through a Nitex filter (pore size, ∼100 μm) to remove larger particles. The samples were then processed in the same manner as seawater to obtain a viral fraction.

Experimental setup.

For the initial experiments, 3 ml of the MICR fraction was added to 100 ml of either the VLP fraction or the DOM fraction (Fig. 1B). The reproducibility of this method was tested by collecting five samples from the same (OB) site (for variation within the site, see Fig. 2B) and taking five subsamples from one of the samples (for variation within a sample, see Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Marine viral community propagation requires an initial viral concentration of >3%, vol/vol, of the natural viral community concentration. Samples from the same carboy (A) and from different carboys but the same site (B) were tested to determine variation by this method. VLP numbers were determined by using direct counting (SYBR Gold epifluorescence microscopy).

To determine if viral communities from one site can be propagated on the microbial community from another, viral concentrates were used instead of the VLP fraction. To do this, the viral community was first concentrated 100-fold by 100-kDa TFF. One milliliter of the viral concentrate was then added to 100 ml of the DOM fraction from a marine site.

In all experiments, the VLP degradation over time was monitored by setting up a control where no MICR inoculum was added. All experimental mixtures were incubated in autoclaved Pyrex glass containers with a screw cap at room temperature.

Subsample collection and preservation.

One- or 5-ml subsamples were collected every 12 h (in some cases, subsamples were collected every 24 h due to time constrains). All subsamples were immediately fixed with equal volumes (4%, vol/vol) of paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in seawater (final concentration, 2%, vol/vol) and stored at 4°C until they were processed for epifluorescence microscopy.

Staining and counting.

One milliliter each of the fixed subsamples was diluted with ultrapure water (Sigma), filtered with 0.02-μm-pore-size Anodiscs (Whatman), and stained with 1× SYBR Gold (Molecular Probes) for 10 min in the dark (modified from the protocol described in reference 30). The stained filters were then mounted on slides by using 50% glycerol in 1× phosphate-buffered saline with 1% ascorbic acid. Images of the stained samples were then captured using a charge-coupled-device camera with a Leica epifluorescence microscope. Images of microbes and VLPs were counted with Adobe Photoshop.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Lytic production by marine viruses.

Wilcox and Fuhrman (49) showed that marine viruses could not propagate when the concentration of viruses was reduced to ∼3% of the natural population size. This occurs, presumably, because the viruses cannot find hosts before they degrade. From this data, it was argued that most viral production in near-shore marine waters is due to lytic production because viral production from lysogens should be concentration independent. As a starting point for our studies, we repeated the Wilcox and Fuhrman protocol to determine reproducibility in (i) five replicates from the same sample and (ii) five samples from the same site. Replicates from the same sample behaved in very similar manners. When the initial viral concentration was approximately equal to that of the natural concentration, the number of VLPs oscillated through degradation-replication cycles. In these replicates, the switch from viral decay to viral production occurred in 12 to 24 h (Fig. 2A). More variability was observed in separate samples from the same site (Fig. 2B). In these samples the viral communities went through repeated degradation-replication cycles, but the timing of the oscillations varied. In both experiments, the microcosms that initially contained natural concentrations of viruses maintained a VLP abundance of >2 × 106 per ml for the course of the experiment (Fig. 2, MICR + VLP + DOM). In contrast, when the initial viral concentration was ∼3% of the original concentration, VLPs were never able to propagate (Fig. 2, MICR + DOM). In these samples the VLP concentrations always remained below 2 × 106 VLPs per ml and usually stayed at <105 VLPs per ml. Our results were similar to those of Wilcox and Fuhrman (49) and show that marine viruses need a minimal concentration (>3% of the natural concentration) in order to find hosts and propagate. Therefore, lytic production is the main form of replication for marine viruses.

Propagation of marine viruses on microbial communities from different marine locations.

To determine if marine viral communities could productively infect microbes from different marine locations, 100× viral concentrates were made from marine water samples gathered from around San Diego, Calif. One milliliter of each concentrate was then added to 100 ml of the DOM fraction from LJ Cove or MB. Three milliliters of the MICR fraction from LJ Cove or MB was then added to the microcosm. In three out of four MB microcosms, the marine viral communities from different sites were able to find hosts and propagate (Fig. 3A). The MB viral community was also able to propagate on microbial communities from LJ Cove. Based on these results, we concluded that marine viral communities were able to productively infect marine microbes from different sites.

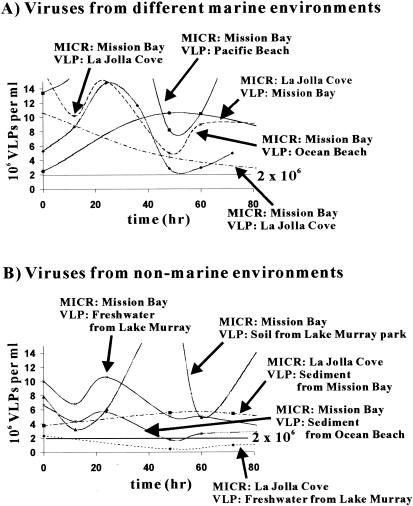

FIG. 3.

Viral communities from different sites were able to propagate on marine microbes. (A) Viral communities from different marine sites were mixed with microbes from MB and the LJ Cove, and VLP numbers were monitored over time. (B) Nonmarine viral communities were added to marine microbial communities, and VLP numbers were monitored over time. MICR, microbial community source; VLP, viral community source. The number of VLPs was determined by epifluorescence microscopy direct counting with SYBR Gold.

Propagation of nonmarine viral communities on marine microbes.

To determine if nonmarine viruses were able to propagate on marine microbes, viral communities were isolated from marine sediment, lake water, and soil. The viral concentrates were added to DOM fractions from MB or LJ Cove and inoculated with 3 ml of the appropriate MICR fraction. As shown in Fig. 3B, VLP abundances oscillated in a manner indicative of degradation-replication cycles observed in the other experiments. Therefore, viruses from the nonmarine environments were able to propagate on the marine microbes. The only exception was the freshwater viral community from LM, which was not able to grow on the LJ Cove microbial communities. In this case, the starting viral concentration was ∼2 × 106 VLPs per ml, which is close to the minimal concentration that was necessary for viral propagation.

Figure 4 shows endpoint comparisons between microcosms inoculated with viral communities with either 3 ml of a MICR fraction or 3 ml of seawater that had been filtered to allow 100-kDa particles to pass through (i.e., controls that did not contain the MICR inoculum). In all cases, except the previously noted LM sample, the presence of a marine microbial community was necessary to prevent degradation of the VLPs. These results show that the nonmarine viruses were able to find hosts and propagate in the marine environment.

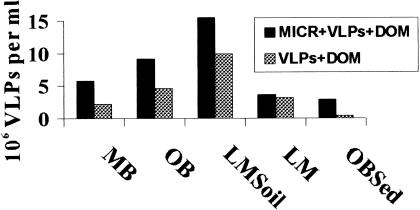

FIG. 4.

VLP production is dependent on the presence of a microbial community. Marine and nonmarine viral concentrates were mixed with MB microbes (MICR + VLP + DOM) or placed in MB seawater that had been filtered to allow 100-kDa particles to pass through (VLP + DOM). VLP numbers were determined after 84 h by use of direct counting. In all cases, the VLP concentrations were higher in microcosms containing the MICR fraction. When no MICR fraction was added to the viruses, virus degradation rates ranged from 5.1 × 106 to 2.5 × 104 day−1 (data not shown). OBSed, sediment from OB; LMSoil, soil from LM Park.

Conclusions.

Our results show that viruses, in particular phages, are able to propagate in different biomes (e.g., soil and seawater). There are two possible explanations for this phenomenon. First, some phages may have broad host ranges that allow them to infect many different microbial species (24). If phages move between environments, a broad host range probably gives them a better chance for survival. In support of this hypothesis, we have found that some identical phage sequences are present in all of the world's major biomes, which suggests that phages indeed move between environments (5). Together, our results suggest that viruses have few geographical boundaries and that the overall biodiversity of viruses may not be as high as previously estimated (cf. references 4, 37, and 39 with reference 47). A second possible explanation of our results is that the microbial hosts also move and grow in different environments. Currently, there is not enough evidence to distinguish between these possibilities.

An important implication of this work is that viruses can move DNA between environments. Viruses are major mechanisms of lateral gene transfer. One of the main differences in the genomic sequences of closely related species of microbes is prophages (8, 16, 18). Viruses carry genes that dramatically change the character of their host. For example, many of the exotoxin genes involved in human diseases are borne by phages (reviewed in reference 13), as are antibiotic resistance genes (28). Within the capsid, virus-borne genes are protected from environmental DNA-damaging agents. In fact, viruses are much more resistant to osmotic, temperature, pressure, and water treatment than are most microbes (29, 31, 41, 42). Because viruses are resistant to water and sewage purification protocols, they may transport exotoxin and antibiotic-resistant genes associated with humans into the marine environment. Recently we have shown that viral particles can be moved from hot springs (∼82°C) to ice (∼0°C) without disrupting the capsid (7). This means that viruses may move genetic information out of the deep, hot biosphere (19) into various freshwater environments.

Besides laterally moving DNA, viruses can influence prokaryotic community structure and biodiversity by killing specific microbial species or strains (40, 43, 44, 51, 53). If there are no geographical boundaries for viral movement, then microbial biodiversity may be constantly changing due to immigration of new viruses. Additionally, as viruses travel between hosts and biomes, they can exchange genes with themselves and their hosts (i.e., mosaic evolution [22, 23]). Therefore, the movement of viruses between biomes will change the genetic diversity and biodiversity of both microbes and viruses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mya Breitbart, Veronica Casas, and Yanan Yu for assistance in field sample collection and useful advice on the manuscript. We especially thank Steve Barlow at the Electron Microscopy Facility at SDSU for technical assistance with the epifluorescence microscope.

This work was supported by grant NSF DEB03-16518.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, M., F. Jimenez-Gomez, J. Rodriguez, and J. Borrego. 2001. Distribution of virus-like particles in an oligotrophic marine environment (Alboran Sea, Western Mediterranean). Microb. Ecol. 42:407-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergh, Ø., K. Y. Børsheim, G. Bratbak, and M. Heldal. 1989. High abundance of viruses found in aquatic environments. Nature 340:467-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Børsheim, K. Y., G. Bratbak, and M. Heldal. 1990. Enumeration and biomass estimation of planktonic bacteria and viruses by transmission electron microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:352-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breitbart, M., B. Felts, S. Kelley, J. Mahaffy, J. Nulton, P. Salamon, and F. Rohwer. 2004. Diversity and population structure of a nearshore marine sediment viral community. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271:565-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitbart, M., and F. Rohwer. 2004. Global distribution of nearly identical phage-encoded DNA sequences. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 236:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breitbart, M., P. Salamon, B. Andresen, J. M. Mahaffy, A. M. Segall, D. Mead, F. Azam, and F. Rohwer. 2002. Genomic analysis of uncultured marine viral communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14250-14255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitbart, M., L. Wegley, S. Leeds, T. Schoenfeld, and F. Rohwer. 2004. Phage community dynamics in hot springs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1633-1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casjens, S. 2003. Prophages and bacterial genomics: what have we learned so far? Mol. Microbiol. 49:277-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, F., J.-R. Lu, B. J. Binder, Y. Liu, and R. E. Hodson. 2001. Application of digital image analysis and flow cytometry to enumerate marine viruses stained with SYBR Gold. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:539-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiura, H. X. 2002. Broad host range xenotrophic gene transfer by virus-like particles from a hot spring. Microb. Environ. 17:53-58. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danovaro, R., A. Dell'Anno, A. Trucco, M. Serresi, and S. Vanucci. 2001. Determination of virus abundance in marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1384-1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danovaro, R., and M. Serresi. 2000. Viral density and virus-to-bacterium ratio in deep-sea sediments of the Eastern Mediterranean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1857-1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis, B. M., and M. K. Waldor. 2002. Mobile genetic elements and bacterial pathogenesis, p. 1040-1055. In N. L. Craig, R. Gragie, M. Gellert, and A. M. Lambowitz (ed.), Mobile DNA II. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 14.Demuth, J., H. Neve, and K.-P. Witzel. 1993. Direct electron microscopy study on the morphological diversity of bacteriophage populations in Lake Pluβsee. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3378-3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyall-Smith, M., S. Tang, and C. Bath. 2003. Haloarcheal viruses: how diverse are they? Res. Microbiol. 154:309-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards, R. A., G. J. Olsen, and S. R. Maloy. 2002. Comparative genomics of closely related salmonellae. Trends Microbiol. 10:94-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuhrman, J. A. 1999. Marine viruses and their biogeochemical and ecological effects. Nature 399:541-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gogarten, J., W. Doolittle, and J. Lawrence. 2002. Prokaryotic evolution in light of gene transfer. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19:2226-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold, T. 1992. The deep hot biosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guixa-Boixareu, N., J. Calderon-Paz, M. Heldal, G. Bratbak, and C. Pedros-Alio. 1996. Viral lysis and bacterivory as prokaryotic loss factors along a salinity gradient. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 11:215-227. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hara, S., K. Terauchi, and I. Koike. 1991. Abundance of viruses in marine waters: assessment by epifluorescence and transmission electron microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2731-2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendrix, R., M. Smith, R. Burns, M. Ford, and G. Hatfull. 1999. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world's a phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2192-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hendrix, R. W., J. G. Lawrence, G. F. Hatfull, and S. Casjens. 2000. The origins and ongoing evolution of viruses. Trends Microbiol. 8:504-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen, E. C., H. S. Schrader, B. Rieland, T. L. Thompson, K. W. Lee, K. W. Nickerson, and T. A. Kokjohn. 1998. Prevalence of broad-host-range lytic bacteriophages of Sphaerotilu natans, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:575-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang, S., G. Steward, R. Jellison, W. Chu, and S. Choi. 2004. Abundance, distribution, and diversity of viruses in alkaline, hypersaline Mono Lake, California. Microb. Ecol. 47:30-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang, S. C., and J. H. Paul. 1998. Gene transfer by transduction in the marine environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2780-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kepner, R. J., R. J. Wharton, and C. Suttle. 1998. Viruses in Antarctic lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42:1754-1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mlynarczyk, G., A. Mlynarcyk, D. Zabicka, and J. Jeljaszewicz. 1997. Lysogenic conversion as a factor influencing the vancomycin tolerance phenomenon in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muniesa, M., F. Lucena, and J. Jofre. 1999. Comparative survival of free Shiga toxin 2-encoding phages and Escherichia coli strains outside the gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5615-5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noble, R. T., and J. A. Fuhrman. 1998. Use of SYBR Green I for rapid epifluorescence counts of marine viruses and bacteria. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 14:113-118. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omura, T., M. Onuma, J. Aizawa, T. Umita, and T. Yagi. 1989. Removal efficiencies of indicator micro-organisms in sewage treatment plants. Water Sci. Technol. 21:119-124. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oren, A., G. Bratbak, and M. Heldal. 1997. Occurrence of virus-like particles in the Dead Sea. Extremophiles 1:143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paul, J., M. Sullivan, A. Segall, and F. Rohwer. 2002. Marine phage genomics. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 133:463-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul, J. H. 1999. Microbial gene transfer: an ecological perspective. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:45-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedros-Alio, C., J. Calderon-Paz, and J. Gasol. 2000. Comparative analysis shows that bacterivory, not viral lysis, controls the abundance of heterotrophic prokaryotic plankton. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 32:157-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedros-Alio, C., J. Calderon-Paz, M. MacLean, G. Medina, C. Marrase, J. Gasol, and N. Boixereu. 2000. The microbial food web along salinity gradients. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 32:143-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedulla, M. L., M. E. Ford, J. M. Houtz, T. Karthikeyan, C. Wadsworth, J. A. Lewis, D. Jacobs-Sera, J. Falbo, J. Gross, N. R. Pannunzio, W. Brucker, V. Kumar, J. Kandasamy, L. Keenan, S. Bardarov, J. Kriakov, J. G. Lawrence, J. William, R. Jacobs, R. W. Hendrix, and G. F. Hatfull. 2003. Origins of highly mosaic mycobacteriophage genomes. Cell 113:171-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Proctor, L. M., J. A. Fuhrman, and M. C. Ledbetter. 1988. Marine bacteriophages and bacterial mortality. EOS 69:1111-1112. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rohwer, F. 2003. Global phage diversity. Cell 113:141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwalbach, M., I. Hewson, and J. Fuhrman. 2004. Viral effects on bacterial community composition in marine plankton microcosms. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 34:117-127. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sinton, L. W., C. H. Hall, P. A. Lynch, and R. J. Davies-Colley. 2002. Sunlight inactivation of fecal indicator bacteria and bacteriophages from waste stabilization pond effluent in fresh and saline waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1122-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slade, J. S. 1989. The survival of human immunodeficiency virus in water, sewage and seawater. Water Sci. Technol. 21:55-59. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thingstad, T. 2000. Elements of a theory for the mechanisms controlling abundance, diversity, and biogeochemical role of lytic bacterial viruses in aquatic systems. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45:1320-1328. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thingstad, T. F., and R. Lignell. 1997. Theoretical models for the control of bacterial growth rate, abundance, diversity and carbon demand. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 13:19-27. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torrella, F., and R. Y. Morita. 1979. Evidence by electron micrographs for a high incidence of bacteriophage particles in the waters of Yaquina Bay, Oregon: ecological and taxonomical implications. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 37:774-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vrede, K., U. Stensdotter, and E. Lindstorm. 2003. Viral and bacterioplankton dynamics in two lakes with different humic contents. Microb. Ecol. 46:406-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whitaker, R., D. Grogan, and J. Taylor. 2003. Geographic barriers isolate endemic populations of hyperthermophilic Archaea. Science 301:976-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wichels, A., S. S. Biel, H. R. Gelderblom, T. Brinkhoff, G. Muyzer, and C. Schütt. 1998. Bacteriophage diversity in the North Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4128-4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilcox, R. M., and J. A. Fuhrman. 1994. Bacterial viruses in coastal seawater: lytic rather than lysogenic production. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 114:35-45. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williamson, K. E., K. E. Wommack, and M. Radosevich. 2003. Sampling natural viral communities from soil for culture-independent analyses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6628-6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winter, C., A. Smit, G. J. Herndl, and M. G. Weinbauer. 2004. Impact of virioplankton on archaeal and bacterial community richness as assessed in seawater batch cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:804-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wommack, K. E., and R. R. Colwell. 2000. Virioplankton: viruses in aquatic ecosystems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol Rev. 64:69-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wommack, K. E., J. Ravel, R. T. Hill, J. Chun, and R. R. Colwell. 1999. Population dynamics of Chesapeake Bay virioplankton: total community analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:231-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]