Abstract

A total of 502 Listeria monocytogenes isolates from food and 492 from humans were subtyped by EcoRI ribotyping and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the virulence gene hly. Isolates were further classified into genetic lineages based on subtyping results. Food isolates were obtained through a survey of selected ready-to-eat food products in Maryland and California in 2000 and 2001. Human isolates comprised 42 isolates from invasive listeriosis cases reported in Maryland and California during 2000 and 2001 as well as an additional 450 isolates from cases that had occurred throughout the United States, predominantly from 1997 to 2001. Assignment of isolates to lineages and to the majority of L. monocytogenes subtypes was significantly associated with the isolate source (food or human), although most subtypes and lineages included both human and food isolates. Some subtypes were also significantly associated with isolation from specific food types. Tissue culture plaque assay characterization of the 42 human isolates from Maryland and California and of 91 representative food isolates revealed significantly higher average infectivity and cell-to-cell spread for the human isolates, further supporting the hypothesis that food and human isolates form distinct populations. Combined analysis of subtype and cytopathogenicity data showed that strains classified into specific ribotypes previously linked to multiple human listeriosis outbreaks, as well as those classified into lineage I, are more common among human cases and generate larger plaques than other subtypes, suggesting that these subtypes may represent particularly virulent clonal groups. These data will provide a framework for prediction of the public health risk associated with specific L. monocytogenes subtypes.

Listeria monocytogenes is an intracellular pathogen that can cause invasive disease in humans and animals (32, 40). Approximately 99% of human listeriosis infections appear to be food borne (23). While L. monocytogenes has been isolated from a variety of raw and ready-to-eat (RTE) foods, most human listeriosis infections appear to be caused by consumption of RTE foods that permit postcontamination growth of this pathogen (6). Listeriosis is estimated to be responsible for about 500 deaths per year in the United States, accounting for 28% of annual deaths attributable to known food-borne pathogens, second only to deaths due to Salmonella infections (23).

L. monocytogenes strains group into two major divisions, designated lineages I and II, as shown by application of a number of molecular subtyping strategies, including ribotyping, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and virulence gene sequencing (41). Strains of serotypes 1/2b, 4b, 3b, and 3c consistently group into lineage I, while serotype-1/2a, -1/2c, and -3a strains group into lineage II (25). L. monocytogenes lineage III strains represent a third, distinct taxonomic group (41), which predominantly includes serotype-4a and -4c strains (25). Some previous studies have suggested that L. monocytogenes subtypes and lineages differ in their associations with specific host and nonhost environments (14, 16, 17, 27, 28, 30, 42). For example, the majority of sporadic human listeriosis cases appear to be caused by serotype-4b and -1/2b strains, while most human listeriosis outbreaks have been caused by serotype-4b strains (41, 42). Rarely, outbreaks have been caused by non-4b serotypes. For example, a serotype-3a strain outbreak was linked to contaminated butter in Finland (22), and a serotype-1/2a outbreak of gastrointestinal listeriosis was linked to sliced turkey in the United States (11). Previous studies have also shown that lineage I strains are more common among human listeriosis cases and outbreaks than among animal cases, while lineage III strains are significantly more common among animal listeriosis cases than among human cases (17). From a biological perspective, however, clear correlations between specific genetic types or clonal groups and virulence characteristics remain to be established (19, 26, 30, 42).

We hypothesize that robust identification of specific associations between L. monocytogenes subtypes and specific hosts or environmental niches will require analyses of both molecular subtyping and pathogenicity characteristics of large numbers of isolates. The majority of previously reported studies that have probed associations between L. monocytogenes molecular subtypes and human clinical cases have used relatively small human, animal, and food isolate data sets; for example, the isolate sets used in references 3, 17, 27, and 28 all included fewer than 250 isolates in total. In this report, we describe the results of molecular subtyping of 502 food isolates and 492 human isolates of L. monocytogenes by using automated EcoRI ribotyping and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the virulence gene hly (17, 42). Although multienzyme ribotyping or other methods (e.g., PFGE) may provide greater discriminatory capabilities (1, 21), single-enzyme EcoRI ribotyping was chosen as a subtyping method for this study because (i) automated ribotyping provides highly standardized results (4), which is a prerequisite for subtyping large isolate sets; (ii) EcoRI ribotyping targets conserved chromosomal genetic characteristics and thus allows for reliable grouping of isolates (35); and (iii) large L. monocytogenes EcoRI ribotype data sets for human, animal, and food isolates were available (5, 17, 35) for comparisons with subtype data generated in this study. The food isolates used in this study were obtained through a large-scale prospective survey of a variety of commercial RTE food products in Maryland and Northern California in 2000 and 2001 (13). Forty-two of the human isolates were obtained from cases of human invasive listeriosis reported from the same regions during the same period. Molecular subtype and tissue culture cytopathogenicity data for these food and human isolates have not been reported previously. To allow a broader comparison between L. monocytogenes subtypes associated with human clinical cases and the RTE food isolates, an additional 450 L. monocytogenes isolates from cases of human listeriosis that occurred throughout the United States from 1997 to 2001 were also included in this study. A tissue culture plaque assay (36, 39) was used to measure the pathogenic potentials of selected isolates.

Based on characterization of the nearly 1,000 human and food L. monocytogenes isolates described above, we demonstrate that L. monocytogenes strains isolated from foods and those isolated from humans represent statistically distinct but overlapping populations. The data reported here thus provide a framework for evaluating the public health risk associated with different L. monocytogenes subtypes. As some L. monocytogenes ribotypes were significantly associated with isolation from specific types of food, our results also illustrate the value of a large-scale database of L. monocytogenes subtypes obtained from a wide variety of foods, which may enable rapid prediction of the most likely food source(s) responsible for an emerging listeriosis outbreak.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

L. monocytogenes food isolates were obtained through a previously described large-scale food survey (9, 13). As part of this survey, more than 30,000 samples representing seven selected RTE food categories (luncheon meats, deli salads, fresh soft “Hispanic-style” cheeses, bagged salads, blue-veined and mold-ripened cheeses, smoked seafood, and seafood salads) were collected in Maryland and Northern California during 2000 and 2001. Isolates used in this study were independently obtained from different, individual food samples. Specifically, a total of 577 food samples tested positive for L. monocytogenes by use of DNA-based screening methods; putative L. monocytogenes isolates were obtained from 505 of these samples (13). Among these 505 food isolates, the EcoRI ribotyping performed in the study described here identified three Listeria spp. other than L. monocytogenes. The initial misidentification of these isolates was further confirmed by negative results with an L. monocytogenes-specific hly PCR for each isolate; these three isolates were eliminated from further analyses. Forty-two human clinical isolates of L. monocytogenes, representing all reported isolates for human invasive listeriosis cases in Maryland and Northern California in 2000 and 2001, were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To provide a comprehensive comparison between human and food isolates and to enable balanced statistical analyses, an additional 450 L. monocytogenes isolates from invasive human listeriosis cases were selected from the Cornell Listeria Strain Collection (CLSC). The 450 human clinical L. monocytogenes isolates included in this study were obtained from patients with listeriosis symptoms who resided predominantly in New York, Connecticut, Ohio, and Michigan, as well as in a few other U.S. states; most isolates were obtained between 1997 and 2002. The CLSC isolates were characterized for ribotype and hly allele type (see below) upon entry into our strain collection. To avoid overrepresentation of a given outbreak in our analyses, if a single-source cluster of listeriosis cases was represented by multiple isolates in our collection, only one isolate from each cluster was included in the present study. Subtype, virulence, and other data (including ribotype images) for all isolates used in this study are publicly available in the searchable PathogenTracker database (www.pathogentracker.net).

Molecular characterization.

For all isolates, the L. monocytogenes virulence gene encoding listeriolysin O (hly) was screened for allelic polymorphisms by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism using the restriction enzymes HhaI and HpaII, as previously described (42). One of eight previously described allelic types (42) was assigned to each isolate based on the restriction pattern generated. Two isolates with a pattern that did not match any type described by Wiedmann et al. (42) were assigned a new type, hly type 1d.

EcoRI ribotyping was performed as previously described (5, 15, 17), by using the RiboPrinter Microbial Characterization system (Qualicon, Wilmington, Del.). Ribotype patterns were analyzed by using the RiboPrinter custom software, which normalizes fragment pattern data for band intensity and relative band size. This software compares each banding pattern to a database of previously observed types and assigns it a DuPont identification number (ID) (e.g., DUP-1044) using a proprietary algorithm. Pattern assignments were confirmed by visual inspection. If visual inspection found that a given DuPont ID included more than one distinct ribotype pattern, each pattern was designated by an alphabetically assigned additional letter (e.g., DUP-1044A and DUP-1044B represent two distinct ribotype patterns within DuPont ID DUP-1044). Distinct ribotype patterns within a given DuPont ID generally differed by the position of a single weak band. If a newly generated ribotype pattern did not match a preexisting DuPont ID pattern with a similarity of >0.85, a type designation was assigned manually based on the “ribogroup” that had been assigned by the instrument (e.g., ribogroup 116-110-S-2).

Isolates were assigned to genetic lineage I, II, or III based on EcoRI ribotypes and hly allelic types, as previously described (42). Briefly, hly type 1 strains were assigned to lineage I. Strains with hly type 2, 2b, or 2c were assigned to lineage II, and strains of hly type 1b, 1c, 1d, 4a, or 4b were assigned to lineage III. In general, ribotype patterns are also associated with a specific lineage (42). For 20 isolates, however, the lineage assignment based on the hly type appeared inconsistent with that based on the ribotype. Final lineage assignments were resolved by using additional subtyping methods, including actA sequencing and 16S rRNA sequencing, as previously described (42). The strategies employed provided complete and consistent subtyping data and lineage assignments for 990 of 994 isolates. For three isolates (all of ribotype 116-110-S-2), no lineage could be assigned; these isolates were excluded from statistical analyses of associations involving lineage. One isolate, despite confirmation of hly type 1, was assigned to lineage III based on ribotype (DUP-1061A), actA sequence, and 16S rRNA sequence data (42). This isolate was included in all statistical analyses.

In vitro cytopathogenicity assay.

The cytopathogenicities of all 42 human L. monocytogenes isolates from Maryland and California and of 91 selected food isolates from the same regions were examined by using a plaque assay with mouse L cells, which was performed essentially as described previously (36, 39). The 91 food isolates were chosen to represent all of the 36 ribotypes found among the 502 food isolates and to include isolates from multiple different food sources for each ribotype, if available. As many as six isolates were selected for each ribotype. Mouse L cells were grown to a confluent monolayer as previously described (39). L. monocytogenes isolates were grown overnight to stationary phase at 30°C without shaking, serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline solution (pH 7.4), and inoculated onto the L cell monolayer (two wells per isolate: one well with 5 μl of a 10−2 dilution and one well with 15 μl of a 10−3 dilution). Serial dilutions of the inoculum were plated on brain heart infusion agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) to determine the number of CFU used for inoculation. Each experiment included two wells of the reference strain 10403S (2) (ribotype DUP-1030A, hly type 2, lineage II) as an internal standard. Infected L cell monolayers were incubated at 37°C for 3 days. Plates were imaged by using an Epson (Long Beach, Calif.) Perfection 1650 digital scanner, and plaque areas were measured with SigmaScan Pro software (version 5.0; Statistical Solutions, Saugus, Mass.). For each isolate, 25 individual plaque areas were averaged to establish the mean plaque area. “Infectivity,” i.e., the efficiency of plaque formation, was calculated as CFU per PFU. Both plaque area and CFU per PFU were expressed as percentages of values for the reference strain 10403S, which were taken as 100%. Strain 10403S has previously been shown to provide a suitable internal reference for the plaque assay, because plaque areas for the majority of wild-type L. monocytogenes isolates are within 40% of the plaque area for this strain (30, 42). The plaque assay was performed in duplicate for all isolates, and the mean of two independent plaque assay results was used as the value for each isolate.

Statistical analysis.

Summary statistics were generated for all food and human isolates by using Statistix (version 7.0; Analytical Software, Tallahassee, Fla.). For statistical purposes, ribotypes were grouped such that there were at least 10 observations for each category; ribotypes that were identified fewer than 5 times were classified as “rare ribotypes,” and ribotypes that were identified between 5 and 8 times were classified as “uncommon ribotypes.” No ribotype was identified nine times. Each ribotype that occurred 10 times or more in the data set was considered to represent a separate category. BestFit was used to examine the distribution of plaque assay data (BestFit for Windows, version 2.0d; Palisade Corporation, Newfield, N.Y.). Data on plaque area (relative to the plaque area of the reference strain) were normally distributed, but for infectivity (relative to reference strain infectivity), a log transformation was used to obtain a normal distribution. Observations from non-plaque-forming isolates (n = 4) were excluded from this analysis.

Associations between categorical variables (lineage, hly type, ribotype, food or human, food type) were examined by chi-square analysis (Statistix) or by Fisher's exact test (SAS, release 8.02; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.), as appropriate. Fisher's exact test was used when any expected cell frequency was less than 2 or if more than 20% of the expected cell frequencies were less than 5 (10). First, overall associations between two categorical variables, e.g., the association between ribotype and origin (food versus human), were examined. Subsequently, associations between specific values of categorical variables (the specified value versus all other values), e.g., the association between smoked seafood versus all other foods and ribotype DUP-1045B versus all other ribotypes, were examined. Associations between categorical and continuous variables (plaque area, log-transformed infectivity [non-plaque forming isolates excluded]) were examined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in Statistix.

For all analyses, categories with fewer than five observations were excluded, and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant in the assessment of results. It could be argued that, due to the large number of associations that were tested, the probability of a type 1 error was inflated and the significance threshold should be adjusted to compensate for that. Rather than lowering the cutoff value for significance to a P value of <0.01 and reporting significance as a binary outcome, we report the observed P values. This allows readers to interpret the data without being limited to a binary classification around an arbitrary threshold for significance (34).

RESULTS

Lineage and hly types of food and human isolates.

The distribution of L. monocytogenes genetic lineages differed significantly between the 492 human isolates and the 502 food isolates, although no associations were exclusive (Table 1). Lineages I and III were significantly (P < 0.0001 and P < 0.05, respectively) associated with isolation from humans, and lineage II was significantly (P < 0.0001) associated with isolation from foods. In contrast, when comparisons were made only between the 42 human isolates from Maryland and California and the 502 food isolates from the same geographic regions and time period, no significant differences were observed in the distribution of food and human isolates among lineages.

TABLE 1.

Association of L. monocytogenes lineage and hly allelic types with isolate origin

| Lineage and hly allelic type | No. of isolates from:

|

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foods | Humans | ||

| Lineage I, hly type 1 | 187 | 267 | <0.0001 |

| Lineage II | |||

| hly type 2 | 162 | 194 | <0.05 |

| hly type 2b | 151 | 17 | <0.0001 |

| Total | 313 | 211 | <0.0001b |

| Lineage III | |||

| hly type 1c | 0 | 1 | NA |

| hly type 1c | 1 | 1 | NA |

| hly type 1d | 0 | 2 | NA |

| hly type 4a | 0 | 1 | NA |

| hly type 4b | 1 | 6 | NS |

| Total | 2 | 11 | <0.05 |

| Lineage unknown | |||

| hly type 1 | 0 | 2 | NA |

| hly type 1b | 0 | 1 | NA |

| Total | 0 | 3 | NA |

P values refer to comparisons of the frequency of the lineage and hly type specified in a particular row among food isolates with the frequency among human isolates. P values indicate the significance of the difference in frequency. NA, not applicable (too few observations to warrant statistical analysis); NS, not significant.

The two hly types (2 and 2b) which constitute lineage II have opposite associations with isolation from humans versus foods, so that combined statistical analysis of both hly types as lineage II is not biologically meaningful.

Lineage and hly type are inconsistent for this one isolate; while hly type 1 is normally classified as lineage I, this isolate was assigned to lineage III based on ribotype (DUP-1061A) and actA as well as 16S ribosomal DNA sequence data.

The distribution of hly allelic types also differed significantly between human and food isolates (Table 1), although there were no exclusive associations. hly types 1 and 2 were significantly associated with isolation from humans, and hly type 2b was significantly associated with isolation from foods. Because lineage II is composed of both hly types 2 and 2b, the statistically significant association of lineage II with isolation from foods results from the highly significant association of hly type 2b strains with food sources (Table 1). hly allelic types 1c, 1d, and 4a occurred very rarely in the data set (once or twice each) and were excluded from statistical analyses.

Ribotypes of food and human isolates.

A total of 63 ribotypes were found among the 994 isolates examined. Thirty-six ribotypes were found among the 502 food isolates, and 54 ribotypes were found among the 492 human isolates. Thirty-seven ribotypes representing 66 isolates were “rare” (identified one to four times), 8 ribotypes representing 49 isolates were “uncommon” (identified five to eight times), and the remaining 879 isolates all belonged to 1 of 18 “common” ribotypes, with 10 to 160 isolates per ribotype.

There was a statistically significant difference in the distribution of ribotypes among human and food isolates, both overall (χ2 = 314.2; df = 19; P < 0.0001) and for individual ribotypes (Table 2). For example, ribotype DUP-1042B was identified in 3.6% of the food isolates but 14.4% of the human isolates, while ribotype DUP-1062A was found in 30.1% of the food isolates but only 1.8% of the human isolates. Overall, eight common ribotypes and the rare ribotypes as a whole were significantly associated with isolation from humans (Table 2), but only one of these common ribotypes (DUP-1030B) was isolated exclusively from humans. Of the 20 ribotypes occurring only once in the data set, 19 were human isolates and 1 was a food isolate. Six common ribotypes were significantly associated with isolation from food (Table 2), and of these, two (DUP-1042C and DUP-1044E) were found exclusively in food. Four common ribotypes and the uncommon ribotypes as a whole were equally likely to be found among human or food isolates. The majority of the isolates (754 of 994) were assigned to common ribotypes that are significantly, but not exclusively, associated with isolation from either food or humans.

TABLE 2.

Association of L. monocytogenes ribotypes with origin (food or human)

| Ribotype | No. (%) of isolates

|

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Human | ||

| DUP-1030A | 8 (1.6) | 8 (1.6) | NS |

| DUP-1030B | 0 | 10 (2.0) | <0.01 |

| DUP-1038B | 15 (3.0) | 63 (12.8) | <0.0001 |

| DUP-1039A | 12 (2.4) | 31 (6.3) | <0.01 |

| DUP-1039B | 18 (3.6) | 43 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| DUP-1039C | 35 (7.0) | 25 (5.1) | NS |

| DUP-1042A | 11 (2.2) | 15 (3.0) | NS |

| DUP-1042B | 18 (3.6) | 71 (14.4) | <0.0001 |

| DUP-1042C | 14 (2.8) | 0 | <0.001 |

| DUP-1043A | 30 (6.0) | 15 (3.0) | <0.05 |

| DUP-1044A | 11 (2.2) | 28 (5.7) | <0.01 |

| DUP-1044B | 1 (0.2) | 19 (3.9) | <0.0001 |

| DUP-1044E | 10 (2.0) | 0 | <0.01 |

| DUP-1045B | 14 (2.8) | 11 (2.2) | NS |

| DUP-1052A | 58 (11.6) | 34 (6.9) | <0.05 |

| DUP-1053A | 24 (4.8) | 40 (8.1) | <0.05 |

| DUP-1062A | 151 (30.1) | 9 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| DUP-1062D | 28 (5.6) | 1 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

| Rare (found in 1-4 isolates) | 23 (4.6) | 43 (8.7) | <0.01 |

| Uncommon (found in 5-8 isolates) | 21 (4.2) | 28 (5.7) | NS |

| Total | 502 (100.0) | 492 (100.0) | <0.0001b |

P values refer to comparison of the frequency of the ribotype specified in a particular row (versus all other ribotypes) among food isolates and human isolates. NS = not significant.

P value for total refers to the overall analysis of ribotype versus origin.

In vitro cytopathogenicities of food and human isolates.

The results of the plaque assay were expressed as two measures of cytopathogenicity: plaque area, an indicator of the ability to spread between mammalian cells, and CFU per PFU, a measure of infectivity. Each of these measures was expressed as a percentage relative to the value for the reference strain, 10403S, taken as 100%. Larger plaque areas and smaller CFU-per-PFU values are indications of greater cytopathogenicity. A total of 133 isolates (42 human isolates and 91 food isolates) were tested with the plaque assay. Four isolates (one human isolate and three food isolates) formed no plaques, indicating severe defects in cytopathogenicity. These isolates, which were excluded from the statistical analyses of cytopathogenicity results, belonged to ribotypes DUP-1053A (the human isolate), DUP-1043A, DUP-1051D, and DUP-1042B.

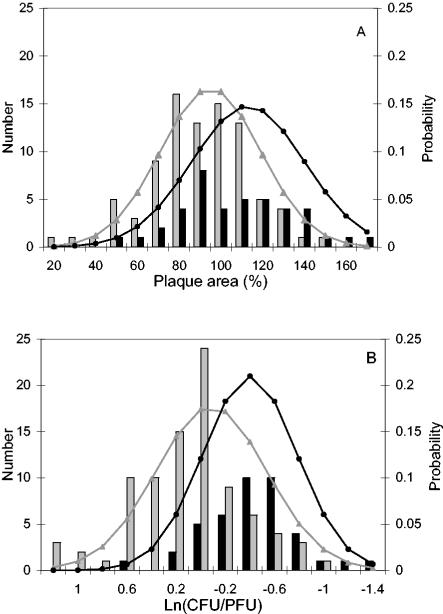

The distribution of plaque areas for the 129 plaque-forming strains was normal, with a mean of 101% and a standard deviation (SD) of 26%. When human and food isolates were considered separately, the distribution of plaque areas within each source type was still normal. Plaques from human isolates (n = 41; mean, 113%, SD, 27%) were larger (P < 0.001 by ANOVA) than plaques from food isolates (n = 88; mean, 95%; SD, 24%), in spite of the fact that plaque areas for the two populations overlapped (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of plaque area (A) and infectivity (B) for 41 human isolates and 88 food isolates of L. monocytogenes tested in a mouse L cell plaque assay. Data for four isolates that formed no plaques were not included in this figure. Plaque area and infectivity (expressed as log-transformed CFU per PFU) are given relative to those of the reference strain, 10403S. Grey and black bars represent the numbers of food and human isolates, respectively. Grey and black lines represent the normalized probability distributions of results from food and human isolates, respectively.

The CFU-per-PFU values for the 129 plaque-forming strains required a log transformation to achieve a normal distribution among the data. The mean ln(CFU/PFU) was −0.07, and the standard deviation was 0.49, which equates to an average CFU per PFU of 93%. When human and food isolates were considered separately, the distribution of log-transformed infectivity was normal within each source type. Infectivity was significantly higher (P < 0.0001 by ANOVA) for human isolates [n = 41; mean ln(CFU/PFU), −0.40; SD, 0.38; mean CFU/PFU, 67%] than for food isolates [n = 88; mean ln(CFU/PFU), 0.09; SD, 0.46; mean CFU/PFU, 109%], in spite of overlapping infectivity values between the two populations (e.g., some human isolates formed fewer plaques than the majority of food isolates) (Fig. 1B).

Lineage or hly type and in vitro cytopathogenicity.

Lineage I isolates formed significantly (P < 0.001 by ANOVA) larger plaques (n = 56; mean, 110%; SD, 29%) than lineage II isolates (n = 70; mean, 93%; SD, 21%). Isolates of hly type 1 (n = 56; mean, 110%; SD, 29%) also formed significantly larger plaques (P < 0.01 by ANOVA) than isolates of either hly type 2 (n = 59; mean, 94%; SD, 22%) or hly type 2b (n = 11; mean, 89%; SD, 14%). Plaque area did not differ significantly between hly types 2 and 2b. Infectivity did not differ significantly between lineages I and II or between isolates of different hly types. Isolates belonging to other lineages or hly types (n = 3) were excluded from statistical analysis because of the limited number of observations within each of these groups.

Ribotype and in vitro cytopathogenicity.

The association between ribotype and plaque area or infectivity was tested for ribotypes for which plaque assay results were available for at least five isolates (Table 3). By examining all 129 plaque-forming isolates and contrasting one ribotype at a time to all isolates belonging to other ribotypes, three ribotypes were found to differ significantly from the rest in cytopathogenicity. DUP-1038B and DUP-1042B had larger plaque areas than other ribotypes. In contrast, DUP-1053A had lower infectivity than other ribotypes. DUP-1042B, which formed the largest plaques, was represented by 14 isolates, so strains with this ribotype had a considerable impact on the overall average plaque size within the data set. When data from DUP-1042B strains were excluded from this analysis and DUP-1038B was contrasted to the remaining 107 isolates, the difference in plaque area between DUP-1038B and the remaining ribotypes was significant (P < 0.01).

TABLE 3.

Plaque area, infectivity, and association with food or humans as the source for eight common L. monocytogenes ribotypes

| Ribotype | No. of isolates | Plaque area (%)a | CFU/PFU (%)a | Source associationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUP-1038B | 8 | 119* | 95 | H > F**** |

| DUP-1039B | 5 | 97 | 99 | H > F*** |

| DUP-1039C | 11 | 100 | 83 | H = F |

| DUP-1042B | 14 | 126*** | 78 | H > F**** |

| DUP-1042C | 5 | 110 | 129 | F > H*** |

| DUP-1043A | 6 | 101 | 90 | F > H* |

| DUP-1053A | 7 | 94 | 135* | H > F* |

| DUP-1062A | 11 | 97 | 78 | F > H**** |

Plaque area and CFU per PFU (a measure of infectivity) are expressed relative to those of the reference strain, 10403S (2). High values indicate a large plaque area and low infectivity, respectively. Asterisks represent P values for comparison of a specified ribotype versus all other plaque-forming isolates. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

Based on analysis of 502 food isolates and 492 human isolates (Table 2). H > F, ribotype more common among human isolates than among food isolates, H = F, no significant difference in occurrence, F > H, ribotype more common among food isolates than among human isolates. Asterisks represent P values. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

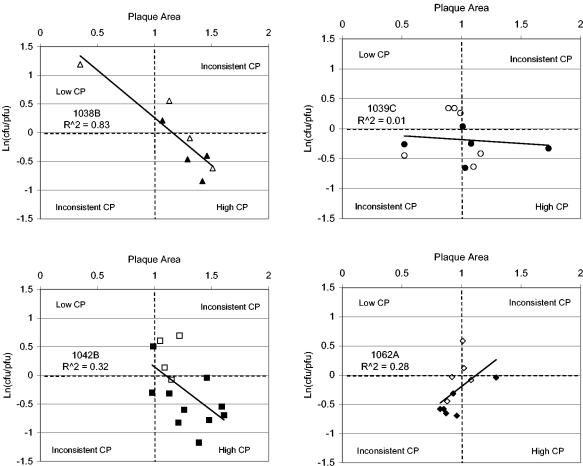

Associations between plaque area and infectivity were evaluated for the four ribotypes for which plaque assay results were available for ≥8 isolates (Fig. 2). For ribotypes DUP-1038B and DUP-1042B, strains with small plaque areas were associated with low infectivity and those with large plaque areas were associated with high infectivity (R2, 0.83 for DUP-1038B and 0.32 for DUP-1042B). No significant association between plaque area and infectivity was observed for DUP-1039C strains (R2 = 0.01). For ribotype DUP-1062A strains, a small plaque area was associated with high infectivity and a large plaque area was associated with low infectivity. DUP-1062A was the most common ribotype found among our food isolates but was rarely isolated from humans (Table 2). The combined results for the four ribotypes show that in vitro cytopathogenicity cannot be defined on the basis of either plaque area or infectivity alone, since correlations between the two can be positive, negative, or absent.

FIG. 2.

Association between two measures of in vitro cytopathogenicity (CP) for the four most common L. monocytogenes ribotypes isolated from foods and humans. Low plaque area and high ln(CFU/PFU) indicate low cytopathogenicity. Plaque area and CFU per PFU are expressed as percentages of those of a reference strain (10403S) assigned a plaque area of 1 and a ln(CFU/PFU) of 0. Open symbols represent food isolates, and closed symbols represent human isolates. The ribotype and the R2 of the association between plaque area and ln(CFU/PFU) are given in each panel.

For ribotypes DUP-1039C, DUP-1042B, and DUP-1062A, results from more than 10 isolates were available, and the in vitro cytopathogenicity of isolates from humans was compared to that of isolates from food within each ribotype. For ribotype DUP-1039C, there was no difference in ln(CFU/PFU) between food isolates (n = 6) and human isolates (n = 5), but for ribotypes DUP-1042B and DUP-1062A, human isolates had significantly higher infectivity than food isolates (for DUP-1042B, nfood = 4, nhuman = 10, and P < 0.01; for DUP-1062A, nfood = 5, nhuman = 6, and P < 0.05). Human and food isolates within these three ribotypes did not differ in plaque area.

Association between molecular types and food types.

When associations between ribotypes and isolation from specific foods were tested as two-by-two tables (a specified ribotype or other ribotypes versus a specified food or other foods), many ribotypes showed over- or underassociation with particular food types, and some of these associations were highly significant (P < 0.001) and nearly exclusive (Table 4). For example, ribotype DUP-1062D was isolated 26 times from smoked seafood and only once from a different type of food. For eight of the nine ribotypes that were highly (P < 0.001) associated with a specific food, food isolates had been obtained from both food sampling sites (Maryland and California). The only exception is ribotype DUP-1045B, which was highly significantly associated with isolation from smoked seafood, and for which all 11 smoked-seafood isolates were obtained from foods collected in California. In addition, the two ribotypes associated with isolation from seafood salads were isolated predominantly from samples collected in Maryland (11 of the 12 DUP-1042B isolates and 44 of the 48 DUP-1062A isolates were from samples collected in Maryland; overall, 82 of 104 seafood salad isolates were from Maryland). The overall association between ribotype and food type was not examined because the large number of possible combinations with low expected values would diminish the value of this comparison.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of L. monocytogenes ribotypes among different food types

| Ribotype | No. of isolatesa from:

|

Total no. of isolatese | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deli salad | Luncheon meat | Bagged salad | BV/MR cheeseb | FS cheesec | Smoked seafood | Seafood salad | ||

| 1030Ad | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 1038B | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 16 |

| 1039A | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 12 |

| 1039C | 2** | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 20** | 7 | 34 |

| 1042A | 8** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 |

| 1042B | 2* | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12*** | 19 |

| 1042C | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6* | 1 | 13 |

| 1043A | 23*** | 0* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 30 |

| 1044A | 1 | 4* | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 11 |

| 1044Bd | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1044E | 0* | 0 | 0 | 10*** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 1045B | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11*** | 0 | 14 |

| 1052A | 26 | 23*** | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 1*** | 59 |

| 1053A | 16*** | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0* | 4 | 24 |

| 1062A | 51 | 14 | 9 | 13* | 2 | 11*** | 48*** | 148 |

| 1062D | 0*** | 0* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 26*** | 0** | 27 |

| 16619 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 18 |

| Rare | 7 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 20 |

| Uncommon | 3 | 8** | 4** | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 22 |

| Total | 173 | 66 | 21 | 28 | 4 | 101 | 104 | 497 |

Asterisks represent the P value of the association between the specified food versus all other foods and the specified ribotype versus all other ribotypes (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Ribotype-food type combinations that are significantly overrepresented are boldfaced; combinations that are significantly underrepresented are italicized.

BV/MR cheese, blue-veined or mold-ripened cheese.

FS cheese, fresh, soft Hispanic-style cheese. Association with ribotypes was not examined because of the low number of observations.

Associations of ribotypes DUP-1030A and DUP-1044B with food type were not examined because of the low number of observations.

The total number of food isolates is 497, because source data were not available for 5 food isolates.

Some foods were also significantly more likely than others to harbor ribotypes that are commonly found in humans. For example, DUP-1053A, which was significantly more common among human isolates than among food isolates (Table 2) and had low infectivity (Table 3), was highly associated with isolation from deli salads (Table 4). Ribotype DUP-1042B, which is associated with humans (Table 2) and forms large plaques (Table 3), was found mostly in seafood salads (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report on the distribution of genotypic and phenotypic characteristics among almost 1,000 L. monocytogenes isolates from either human clinical or food sources. Smaller-scale studies on subtype and/or phenotypic characteristics of L. monocytogenes isolates from humans and foods have been reported previously (3, 27, 28). Our data clearly indicate that human and food isolates of L. monocytogenes represent distinct but overlapping populations. This conclusion is supported by three lines of evidence: (i) the distribution of L. monocytogenes lineages, hly types, and ribotypes differed significantly between the 502 isolates from foods collected in Maryland and Northern California and the 492 human clinical isolates obtained from human listeriosis cases throughout the United States; (ii) the 91 food isolates and 42 human isolates collected in the same region during the same period exhibited significant differences in cytopathogenicity between human and food isolates; (iii) molecular subtypes significantly associated with isolation from human patients also showed higher average in vitro cytopathogenicity, indicative of higher virulence, than subtypes associated with isolation from foods. Our observations are consistent with the hypothesis that L. monocytogenes subtypes may differ in their virulence for humans and/or in potential for food-borne transmission (41, 42). In particular, our data support the notion that L. monocytogenes lineage I strains, which have previously been shown to be the predominant strains associated with human listeriosis cases and outbreaks in multiple countries and continents (41), have a higher likelihood of causing human disease than some or all of the strains grouped into lineage II. We are currently in the process of quantifying these differences by using a previously described L. monocytogenes risk assessment (9), developed on the basis of the food prevalence study (13), which yielded the food isolates used in the study described here.

Human and food isolates represent distinct but overlapping molecular subtype populations.

Analysis of the molecular subtyping data showed that the distribution of L. monocytogenes lineages, hly types, and ribotypes differed significantly between the 502 food isolates from Maryland and Northern California and the entire group of 492 human listeriosis isolates collected from patients in different U.S. states over a period (1997 to 2002) similar to that used for collection of the food isolates (2000 to 2001). The apparent absence of significant differences between the 42 human and 502 food isolates collected from Maryland and California during the same period is most likely explained by the limited statistical power of analyses with a small number of human isolates. Previous, smaller studies have also reported statistically significant but nonexclusive associations between certain L. monocytogenes subtypes and isolation from human clinical specimens or food samples (27, 28), providing additional evidence that L. monocytogenes strains differ in their likelihood of causing human clinical disease.

L. monocytogenes lineages, ribotypes, hly allelic types, and actA sequence types are highly correlated, consistent with the fact that the virulence gene island containing hly and actA is stable and not easily horizontally transferred (42). While the vast majority of lineage I strains are characterized by hly type 1, lineage II includes two main hly types (2 and 2b). Our finding that L. monocytogenes lineage I and hly type 1 strains were significantly more common among human isolates than among food isolates is consistent with previous reports describing the frequent association of serotype-1/2a and -4b strains with human listeriosis cases (14), since serotypes 1/2a and 4b belong to lineage I (25, 41). Lineage I strains also are significantly more likely to be isolated from humans than from animals (17). The significant association of lineage II strains with isolation from foods is true for lineage II strains that also show hly type 2b; lineage II hly type 2 strains are weakly associated with isolation from humans. This finding suggests that these two hly types may differ in their likelihood of causing human disease. One previous study reported that lineage III strains represent about 8% of animal isolates (17). The scarcity of lineage III strains among food and human isolates in the present study may reflect an efficient separation of L. monocytogenes strains associated with animals and farm environments from those associated with humans and food-processing environments. Alternatively, lineage III strains may survive or multiply poorly in food-processing environments, or during food processing and storage.

EcoRI ribotyping data revealed a significant difference in the distribution of ribotypes between food and human isolates. Eight or six ribotypes were significantly associated with isolation from humans or foods, respectively. Interestingly, all three ribotypes that had previously been associated with more than one human listeriosis outbreak (7, 8, 17) were also significantly associated with isolation from humans in our data set. These three “epidemic ribotypes” all belong to lineage I; they include ribotype DUP-1038B, which caused outbreaks in Anjou, France (1976), Nova Scotia, Canada (1981), Vaud, Switzerland (1983 to 1987), and Los Angeles, Calif. (1985) (17), ribotype DUP-1042B, which caused two outbreaks in Massachusetts (1979 and 1983) (17), and ribotype DUP-1044A, which was responsible for two recent U.S. outbreaks that were linked to consumption of contaminated hot dogs (8) and sliced turkey (7).

An additional, particularly striking observation was that one ribotype (DUP-1062A) represented 30.1% of food isolates but only 1.8% of human isolates. We have recently found that ribotype DUP-1062A isolates carry a premature stop codon in the virulence gene inlA and show reduced ability to invade human epithelial Caco-2 cells (unpublished data). Loss of cell wall-bound InlA through naturally occurring premature stop codons has also been shown previously to lead to reduced invasion of human epithelial cells (31). Loss of InlA thus provides a likely biological mechanism underlying the relative infrequency of ribotype DUP-1062A among human isolates, even though this subtype is common among food isolates. These findings support the biological relevance of the associations between specific subtypes and isolation from humans and foods described here.

In vitro cytopathogenicity data support the hypothesis that human and food isolates represent distinct but overlapping populations.

Based on data for 91 representative food isolates and 42 temporally and geographically matched human isolates, we found that, on average, human isolates had significantly greater cytopathogenicities than food isolates, including both a significantly greater ability to invade mouse L cells and an enhanced ability to spread from cell to cell. We also found that lineage I strains (which were associated with isolation from human clinical cases [see above]) produced significantly larger plaques than lineage II strains. This is in agreement with previous studies on human and animal clinical isolates and food isolates of L. monocytogenes, which showed that lineage I strains, on average, formed larger plaques than lineage II strains (42). In addition, isolates representing the epidemic ribotypes DUP-1038B and DUP-1042B also formed larger-than-average plaques in our in vitro pathogenicity assays. Overall, these observations support biological bases underlying the observed differences in subtype association between human and food isolates and further suggest that at least some specific lineage I strains (e.g., strains with ribotype DUP-1038B or DUP-1042B) represent major epidemic clones with enhanced virulence characteristics.

Our data also suggest that in vitro cytopathogenicity may, in some cases, be ribotype specific. In addition to ribotypes DUP-1038B and DUP-1042B, which produced significantly larger plaques than other ribotypes, ribotype DUP-1053A was found to have lower infectivity than other ribotypes. These findings are consistent with studies on food and human isolates using chicken embryo and Caco-2 tissue culture infection assays, which also revealed that some subtypes were more virulent than others (19, 26). The concept of strain-specific virulence characteristics is also supported by the observation that the correlation between the two measures of cytopathogenicity (plaque size and infectivity) differed among ribotypes. However, isolates within a given ribotype also exhibited a range of cytopathogenicities. For example, for two out of three ribotypes for which more than 10 isolates were tested in plaque assays, within a given ribotype, isolates from humans had significantly higher average cytopathogenicity than isolates from foods. Whether cytopathogenicity can increase as a result of passage through a human or whether more-cytopathogenic isolates were more likely to cause human disease remains speculative, as previously acknowledged (26). Overall, our results indicate that considerable variation in cytopathogenicity exists, even within a given ribotype. Use of more-discriminatory subtyping and characterization methods, such as PFGE, multilocus sequence typing, or sequencing of virulence genes will be necessary to determine whether these cytopathogenicity differences reflect the existence of different subtypes within a given ribotype.

It should be emphasized that isolates with low cytopathogenicity in vitro may still cause human disease. For example, ribotype DUP-1053A showed lower infectivity and formed smaller plaques than other ribotypes but was significantly more common among human isolates than among food isolates. Conversely, ribotype DUP-1042C, which was associated exclusively with isolation from foods, was characterized by high in vitro cytopathogenicity measures. Measurement of in vitro cytopathogenicity in murine L cells is unlikely to measure all of the factors involved in in vivo virulence across all species. For example, internalin A-mediated invasion (40) cannot be assessed in mouse L cells, since L. monocytogenes internalin A interacts with human E-cadherin but not with murine E-cadherin (20, 24). In spite of recognized shortcomings, however, the plaque assay used here provides a relatively straightforward, quantitative measure of selected virulence characteristics. In studies with defined L. monocytogenes mutants, plaque assay results have been shown to correlate with strain virulence in the murine system and to sensitively detect mutations in genes affecting cell-to-cell spread (37).

Some molecular types are associated with specific food types.

A number of ribotypes were significantly over- or underassociated with one or two specific food categories; several associations were highly significant and nearly exclusive, suggesting underlying biological or epidemiological explanations. Associations between specific bacterial subtypes and food types have also been observed for other pathogens. For example, Clostridium botulinum type E strains are strongly associated with isolation from seafood, because these strains are adapted to survival in aquatic sediments (38). Similarly, it is possible that some L. monocytogenes subtypes are particularly well adapted to surviving in specific food types. For example, DUP-1062A and DUP-1062D were both significantly associated with isolation from seafood. Previous studies of L. monocytogenes in smoked seafood and in seafood-processing plants have commonly resulted in isolation of ribotype DUP-1062 strains (which include both DUP-1062A and DUP-1062D) (12, 29, 30). Another possible explanation for the association of certain ribotypes with specific food types is that these ribotypes are processing plant specific. In agreement with this hypothesis, a variety of studies have shown that specific L. monocytogenes subtypes can persist in food-processing environments for months to years (12, 18, 29, 41) and the source of at least one listeriosis outbreak has been traced to a strain persisting in a single processing facility (18). In our study, ribotype DUP-1044E, which was isolated only from blue-veined and mold-ripened cheese, might be a persistent environmental contaminant in a cheese plant with national product distribution. Our observations suggest that further work toward identifying specific associations between food types and L. monocytogenes subtypes may enable more-rapid tracking of future listeriosis outbreaks to likely food sources (22).

Conclusions.

Our results show that the L. monocytogenes population associated with the RTE foods tested differed significantly from the population associated with human clinical cases, both in subtype composition and in the ability to infect mammalian cells in tissue culture. These findings support the existence of virulence and transmissibility differences among L. monocytogenes subtypes. An understanding of the variability of strains encountered in humans, foods, animals, and the environment and the range of virulence characteristics expressed by different strains will contribute to improved assessment of the public health risk posed by L. monocytogenes (6, 9, 33).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the North American Branch of the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI N.A.) (to M.W.). Funding for this work was provided in part by the National Alliance for Food Safety (NAFS), through a cooperative agreement with USDA-ARS. The NAFS-supported project was a collaborative effort among S. Kathariou (North Carolina State University), L.-A. Jaykus (North Carolina State University), I. Wesley (National Animal Disease Center, Ames, Iowa), and K.J.B.

The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of ILSI N.A.

We thank M. Roma and K. Windham for technical assistance with subtyping and B. Sauders for insightful and helpful discussions. We also thank various collaborators who contributed human L. monocytogenes isolates to our strain collection, including J. Hibbs, N. Dumas, D. Morse, and D. J. Schoonmaker-Bopp (New York State Department of Health), L. Kornstein (New York City Department of Health), T. Bannerman (Ohio Department of Health), and J. P. Massey and S. Dietrich (Michigan Department of Community Health).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarnisalo, K., T. Autio, A.-M. Sjöberg, J. Lundén, H. Korkeala, and M.-L. Suihko. 2003. Typing of Listeria monocytogenes isolates originating from the food processing industry with automated ribotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Food Prot. 66:249-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop, D. K., and D. J. Hinrichs. 1987. Adoptive transfer of immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. J. Immunol. 139:2005-2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boerlin, P., and J. C. Piffaretti. 1991. Typing of human, animal, food, and environmental isolates of Listeria monocytogenes by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1624-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce, J. 1996. Automated system rapidly identifies and characterizes microorganisms in food. Food Technol. 50:77-81. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruce, J. L., R. J. Hubner, E. M. Cole, C. I. McDowell, and J. A. Webster. 1995. Sets of EcoRI fragments containing ribosomal RNA sequences are conserved among different strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5229-5233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration; Food Safety and Inspection Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Quantitative assessment of relative risk to public health from foodborne Listeria monocytogenes among selected categories of ready-to-eat foods. [Online.] http://www.foodsafety.gov/∼dms/lmr2-toc.html.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Outbreak of listeriosis—northeastern United States, 2002. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:950-951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Update: multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States, 1998-1999. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 47:1117-1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Y., W. H. Ross, V. N. Scott, and D. E. Gombas. 2003. Listeria monocytogenes: low levels equal low risk. J. Food Prot. 66:570-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson-Saunders, B., and R. G. Trapp. 1994. Basic and clinical biostatistics, 2nd ed. Appleton & Lange, Norwalk, Conn.

- 11.Frye, D. M., R. Zweig, J. Sturgeon, M. Tormey, M. LeCavalier, I. Lee, L. Lawani, and L. Mascola. 2002. An outbreak of febrile gastroenteritis associated with delicatessen meat contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:943-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gendel, S. M., and J. Ulaszek. 2000. Ribotype analysis of strain distribution in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 63:179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gombas, D. E., Y. Chen, R. S. Clavero, and V. N. Scott. 2003. Survey of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods. J. Food Prot. 66:559-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graves, L. M., B. Swaminathan, and S. B. Hunter. 1999. Subtyping Listeria monocytogenes, p. 279-297. In E. T. Ryser and E. H. Marth (ed.), Listeria, listeriosis, and food safety, 2nd ed. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 15.Hubner, R. J., E. M. Cole, J. L. Bruce, C. I. McDowell, and J. A. Webster. 1995. Predicted types of Listeria monocytogenes created by the positions of EcoRI cleavage sites relative to rRNA sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5234-5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaradat, Z. W., G. E. Schutze, and A. K. Bhunia. 2002. Genetic homogeneity among Listeria monocytogenes strains from infected patients and meat products from two geographic locations determined by phenotyping, ribotyping, and PCR analysis of virulence genes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 76:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffers, G. T., J. L. Bruce, P. L. McDonough, J. Scarlett, K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann. 2001. Comparative genetic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from human and animal listeriosis cases. Microbiology 147:1095-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kathariou, S. 2002. Listeria monocytogenes virulence and pathogenicity, a food safety perspective. J. Food Prot. 65:1811-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen, C. N., B. Nørrung, H. M. Sommer, and M. Jakobsen. 2002. In vitro and in vivo invasiveness of different pulsed-field gel electrophoresis types of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5698-5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lecuit, M., S. Dramsi, C. Gottardi, M. Fedor-Chaiken, B. Gumbiner, and P. Cossart. 1999. A single amino acid in E-cadherin responsible for host specificity towards the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. EMBO J. 18:3956-3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louie, M., P. Jayaratne, I. Luchsinger, J. Devenish, J. Yao, W. F. Schlech, and A. Simor. 1996. Comparison of ribotyping, arbitrarily primed PCR, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for molecular typing of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:15-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyytikäinen, O., T. Autio, R. Maijala, P. Ruutu, T. Honkanen-Buzalski, M. Miettinen, M. Hatakka, J. Mikkola, V.-J. Anttila, T. Johansson, L. Rantala, T. Aalto, H. Korkeala, and A. Siitonen. 2000. An outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 3a infections from butter in Finland. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1838-1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mead, P. S., L. Slutsker, V. Dietz, L. F. McCaig, J. S. Bresee, C. Shapiro, P. M. Griffin, and R. V. Tauxe. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:607-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mengaud, J., H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, R.-M. Mège, and P. Cossart. 1996. E-cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of L. monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Cell 84:923-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nadon, C. A., D. L. Woodward, C. Young, F. G. Rodgers, and M. Wiedmann. 2001. Correlations between molecular subtyping and serotyping of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2704-2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nørrung, B., and J. K. Andersen. 2000. Variations in virulence between different electrophoretic types of Listeria monocytogenes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 30:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nørrung, B., B. Ojeniyi, and M. Badaki. 1999. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from foods and human listeriosis in Denmark, p. 576-578. In A. C. J. Tuijtelaars, R. A. Samson, F. M. Rombouts, and S. Notermans (ed.), Food microbiology and food safety into the next millenium. Proceedings of the 17th International Conference of the International Committee on Food Microbiology and Hygiene. Foundation for Food Microbiology '99, TNO, Zeist, The Netherlands.

- 28.Nørrung, B., and N. Skovgaard. 1993. Application of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis in studies of the epidemiology of Listeria monocytogenes in Denmark. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2817-2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norton, D. M., M. A. McCamey, K. L. Gall, J. M. Scarlett, K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann. 2001. Molecular studies on the ecology of Listeria monocytogenes in the smoked fish processing industry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:198-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norton, D. M., J. M. Scarlett, K. Horton, D. Sue, J. Thimothe, K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann. 2001. Characterization and pathogenic potential of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the smoked fish industry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:646-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olier, M., F. Pierre, S. Rousseaux, J. P. Lemaitre, A. Rousset, P. Piveteau, and J. Guzzo. 2003. Expression of truncated internalin A is involved in impaired internalization of some Listeria monocytogenes isolates carried asymptomatically by humans. Infect. Immun. 71:1217-1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts, A. J., and M. Wiedmann. 2003. Pathogen, host and environmental factors contributing to the pathogenesis of listeriosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60:1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rocourt, J., P. BenEmbarek, H. Toyofuku, and J. Schlundt. 2003. Quantitative risk assessment of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods: the FAO/WHO approach. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 35:263-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothman, K. J., and S. Greenland. 1998. Approaches to statistical analysis, p. 183-199. In K. J. Rothman and S. Greenland (ed.), Modern epidemiology. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 35.Sauders, B. D., E. D. Fortes, D. L. Morse, N. Dumas, J. A. Kiehlbauch, Y. H. Schukken, J. R. Hibbs, and M. Wiedmann. 2003. Molecular subtyping to detect human listeriosis clusters. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:672-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith, G. A., H. Marquis, S. Jones, N. C. Johnston, D. A. Portnoy, and H. Goldfine. 1995. The two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogenes have overlapping roles in escape from a vacuole and cell-to-cell spread. Infect. Immun. 63:4231-4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith, G. A., J. A. Theriot, and D. A. Portnoy. 1996. The tandem repeat domain in the Listeria monocytogenes ActA protein controls the rate of actin-based motility, the percentage of moving bacteria, and the localization of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein and profilin. J. Cell Biol. 135:647-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith, L. D. S., and H. Sugiyama. 1988. Botulism: the organism, its toxins, the disease, 2nd ed. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Ill.

- 39.Sun, A. N., A. Camilli, and D. A. Portnoy. 1990. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes small-plaque mutants defective for intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infect. Immun. 58:3770-3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vázquez-Boland, J. A., M. Kuhn, P. Berche, T. Chakraborty, G. Domínguez-Bernal, W. Goebel, B. González-Zorn, J. Wehland, and J. Kreft. 2001. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:584-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiedmann, M. 2002. Molecular subtyping methods for Listeria monocytogenes. J. AOAC Int. 85:524-531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiedmann, M., J. L. Bruce, C. Keating, A. E. Johnson, P. L. McDonough, and C. A. Batt. 1997. Ribotypes and virulence gene polymorphisms suggest three distinct Listeria monocytogenes lineages with differences in pathogenic potential. Infect. Immun. 65:2707-2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]