Abstract

Fecal incontinence is not a diagnosis but a frequent and debilitating common final pathway symptom resulting from numerous different causes. Incontinence not only impacts the patient’s self-esteem and quality of life but may result in significant secondary morbidity, disability, and cost. Treatment is difficult without any panacea and an individualized approach should be chosen that frequently combines different modalities. Several new technologies have been developed and their specific roles will have to be defined. The scope of this review is outline the evaluation and treatment of patients with fecal incontinence.

Keywords: Fecal incontinence, Sphincteroplasty, Sacral nerve stimulation, Endorectal ultrasound, New technologies, Quality of life

Core tip: Fecal incontinence is frequent, under-reported, and lacks a perfect treatment solution. Fecal control is not equivalent to normal sphincter muscles. Other factors such (e.g., stool consistency, rectal reservoir function and elasticity are equally important. Incontinence is rather a symptom than a diagnosis, representing the common final pathway of various etiologies. Measurement of fecal incontinence remains subjective and based on patient reporting. Successful incontinence management combines a thorough understanding of contributing factors, workup and interpretation of individual results, tailoring of individual treatment plan. New technologies are abundant but not indicated for all patients, and objective results often less strong than advertised.

INTRODUCTION

Continence is one of our fundamental expectations and a basic element of quality of life. It reflects the confidence to have in place an adequate perception and control mechanism for stool and urine to allow for a conscious selection of the appropriate timing, location and privacy for voiding and moving the bowels. Continence is the result of a balanced interaction between the anal sphincter complex (“plug”), stool consistency, the rectal reservoir function, and neurological function. Disease processes or structural defects that alter any of these components can lead to the clinical symptom of fecal incontinence.

Fecal incontinence is defined as the involuntary loss of rectal contents (feces, gas) through the anal canal and the inability to postpone an evacuation until socially convenient. Attached to the definition are a time and age component to include a duration of the problem for at least one month and an age of at least 4 years with previously achieved control[1-3]. Depending on the presenting circumstances, fecal incontinence is commonly classified as (1) passive incontinence (involuntary discharge without any awareness); (2) urge incontinence (discharge despite active attempts to retain contents); and (3) fecal seepage (leakage of stool with grossly normal continence and evacuation)[2]. Fecal control is often thought to be synonymous with normal sphincter muscles; however other factors are equally important[4]. Hence, fecal incontinence has to be considered the common final pathway symptom of multiple independent etiologies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Causes of fecal incontinence

| Category | Details |

| Acquired structural abnormalities | Obstetric injury (vaginal delivery) |

| Anorectal surgery (hemorrhoid, fistula, fissure, etc.) | |

| Rectal intussusception/prolapse | |

| Sphincter-sparing bowel resection | |

| Trauma (e.g., pelvic fracture, Anal impalement) | |

| Functional disorders | Chronic diarrhea |

| Irritable bowel disease | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | |

| Radiation proctitis | |

| Malabsorption | |

| Hypersecretory tumors | |

| Fecal impaction (paradoxical diarrhea) | |

| Physical disabilities | |

| Psychiatric disorder | |

| Neurological disorders | Pudendal neuropathy |

| (radiation, diabetes, chemotherapy) | |

| Spinal surgery | |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Dementia | |

| CNS disorder: stroke, trauma, tumor, infection | |

| Spina bifida | |

| Congenital disorders | Imperforate anus |

| Cloacal defect | |

| Spina bifida (myelomeningocele, meningocele) |

Consequences of incontinence (both fecal and urinary) are significant at different levels[4-7]: (1) The patients may develop secondary medical morbidities, such as skin maceration, urinary tract infections, decubitus ulcers, etc; (2) There are substantial direct and indirect financial expenses to the patients (e.g., diapers, clothes, loss of productivity), the employers (days off work), and the insurances (health care cost, unemployment, etc.)[5]; and (3) Most importantly, there is a significant impact on the quality of life (self-esteem, embarrassment, shame, depression, need to organize life around easy access to bathroom, avoidance of enjoyable activities, etc.). Notably, this aspect is not limited to the patient but could to a similar degree affect the patient’s significant others[7].

The purpose of our review is to analyze the complexity and limitations of fecal incontinence management and to correlate basic concepts of etiopathogenesis and work-up on one hand with the treatment options on the other hand. The challenges need to be pointed out to define current options and possible solutions.

Challenge

Treatment for fecal incontinence often is demanding and needs to be tailored to the individual circumstances[8]. Unfortunately and despite of a wealth of data, our knowledge about the physiology and pathophysiology of the anorectal continence remains sketchy in many aspects[3,4,9,10]. In particular, it remains difficult if not impossible to correlate subjective and objective parameters in a way to allow for prediction of outcomes. The matter is further complicated by a striking absence of standardization of definitions and of instruments to measure and quantitate fecal incontinence. Even though there are a number of scoring systems that are commonly used [e.g., Wexner/CCF incontinence score; Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQL) score; Fecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI); St. Marks Incontinence Score (SMIS); etc.)[11], there is none that would include physiologic components or objective test parameters to accurately reflect the clinical severity. Instead, most instruments are based on a subjective patient-reported assessment of severity and frequency.

In the United States, the Cleveland Clinic Florida (Wexner) fecal incontinence score remains the most commonly employed score because of its ease of use (Table 2)[12]: the summary score is derived from 5 parameters whose frequency is each ranked on a scale from 0 (= absent) to 4 (daily): incontinence to gas, to non-formed stool, or to solid stool, need to wear pad, and lifestyle changes. A score of 0 means perfect control, a score of 20 complete incontinence[12]. Unfortunately, the patient’s behavior and coping mechanisms are not taken into consideration and can result in substantial variation of the reported score. For example and solely for the purpose of arguments, if a completely incontinent patient hypothetically spent the whole time on the toilet, there would be no incontinence to gas, liquid or formed stool, no need for a diaper, and therefore the only parameter to count would be a “daily impact on his quality of life”, i.e., a score of 4 (instead of the more appropriate score of 20).

Table 2.

Cleveland Clinic Fecal Incontinence Score[12]

| Parameter |

Frequency |

||||

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Usually | Always | |

| (< 1/mo) | (< 1/wk but ≥ 1/mo) | (< 1/d but ≥ 1/wk) | (≥ 1/d) | ||

| Incontinence to solid stool | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Incontinence to liquid/loose stool | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Incontinence to gas | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Wears pad | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Lifestyle alteration | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Sum of the five parameters: perfect control = 0; complete incontinence = 20.

Epidemiology

Fecal incontinence is very common but because of the associated embarrassment and a common taboo nature, it is under-reported and its true prevalence difficult to reliably assess[13]. Reported estimates of prevalence rates always have to be interpreted with caution and should be seen within their respective context[14]. Depending on the method and strategy of assessment and the target population, such data may not be representative of the whole population but only reflect selected subsets that may be very different from other population segments. Analysis of 14759 participants in the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey revealed a fecal incontinence prevalence of 8.4% among non-institutionalized United States adults with an age-dependent increase over time[14]. International population-based studies suggested a fecal incontinence prevalence of 0.4%-18%[14-17]. A telephone survey in the United States reported a prevalence of 2.2% with a female to male ratio of 63% vs 37%, whereby 30% of the affected interviewees were older than 65 years[18]. Review of outpatient clinic patients revealed a prevalence of 5.6% in general outpatients as opposed to 15.9% in urogynecology patients[16]. A disproportionate fraction of 45%-50% of affected individuals have severe physical and/or mental disabilities, and incontinence is a frequent reason for transfer to nursing homes[19-21].

Etiologies

A vast number of etiologies have been associated with the development of fecal incontinence (see Table 1), including acquired structural abnormalities or congenital malformations, degenerative and functional conditions, or neurological disorders[13]. Diarrhea and altered bowel habits [e.g., from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), diet intolerance, constipation with paradoxical diarrhea and overflow incontinence] is one of the most frequent independent risk factors for incontinence[22]. The most common structural causes, however, are the result of obstetrical injury (often decades before onset of symptoms)[23], anorectal surgeries (hemorrhoidectomy, fistulotomy, sphincterotomy)[24], prolapse[25], anoreceptive intercourse[26], or a status post colo-anal or ileo-anal reconstruction[27].

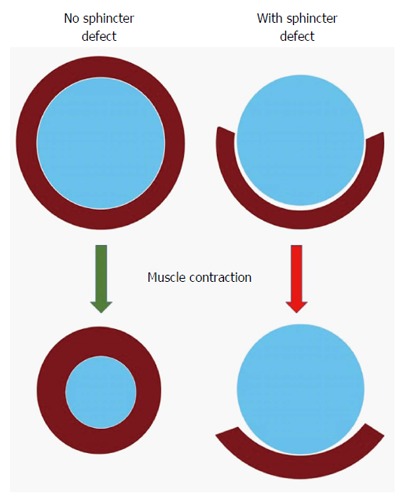

A third or fourth degree obstetrical injury with sphincter disruption is clinically recognized in approximately 3%-8% of all vaginal deliveries. But even uncomplicated first-time vaginal deliveries may reveal an occult sphincter damage in up to 35%, whereby forceps delivery, occipito-posterior presentation of the baby, and prolonged labor are independent risk factors[2]. The controversy whether episiotomies are “good, bad, or ugly” in the first place or because simply done too late in the course of labor goes beyond the focus of this review[28,29]. Occult defects remain silent in two thirds of the individuals, but in one third over time become symptomatic with incontinence or urgency. It is important to note that the extent of a sphincter defect has only limited correlation with the degree of fecal incontinence. Intuitively, a large enough sphincter defect alters the circular muscle contraction with concentric closure of the anal canal into a more curvilinear muscle shortening with decreased force onto the anal canal (Figure 1). Beyond that, however, a sphincter defect rather represents a surrogate parameter for the fact that the entire neuromuscular structures of the pelvic floor have suffered a substantial traumatic impact that goes beyond the simple size measurement of a defect angle. The onset of symptoms may frequently lag behind the time of injury by many years; other factors such as onset of menopause, accelerated aging of the traumatized sphincter structures, or decompensation of coping mechanisms may contribute to that delay.

Figure 1.

Negative impact of sphincter defect: A normal circumferential muscle configuration results in a concentric contraction and narrowing of the anus (left); if there is a segmental defect in the muscle, contraction may result in shortening of the muscle fibers behind the anus without narrowing it (right).

Similar to obstetrical injuries, anorectal surgeries (hemorrhoidectomy, sphincterotomy, fistula surgeries) are frequently identified in patients with symptoms of incontinence. This is at variance with low percentages of incontinence when outcomes of such surgical series are reported. The explanation for this discrepancy may be found in the fact that such observational cohort studies frequently lack long-term follow-up of more than 10 years and hence fail to capture the delayed onset of symptoms to determine the true incidence of this long-term complication.

From physiology to pathophysiology

Successful management of patients with fecal incontinence depends not only on a fundamental knowledge about etiologies, but requires a good understanding of the underlying normal mechanisms and the intricate interaction of different components that contribute to achieving fecal control.

Outlet resistance - anal closure function (“plug”)

There need to be structures and functions in place to create a dynamic barrier with sufficient outlet resistance against a varying range of intrarectal pressures of the feces at rest, or when there is an increase of the intra-abdominal pressure, be it physiologically during a peristaltic wave, or during physical stress and activity[4,30]: (1) Puborectalis sling and external anal sphincter (EAS): This is an array of striated muscles with slow-twitch, fatigue-resistant muscle fibers that at the center and bottom of the pelvic floor. They are innervated by the inferior branch of the pudendal nerve (S3-S4), contribute to about 30%-40% of the anal resting tone (normal reference value: > 50 mmHg)[31], and provide the voluntary sphincter contraction (squeeze pressure) with roughly a doubling of the resting pressure (normal reference value: > 100 mmHg). Puborectalis dysfunction results in complete incontinence, EAS dysfunction in impaired voluntary control (urge incontinence); (2) Internal anal sphincter (IAS): This smooth muscle represents the thickened end in continuation of the muscularis propria of the rectum. It has an autonomic innervation and contributes to an estimated 50%-55% of the resting tone of the anal canal[31]. IAS dysfunction is associated with impaired fine tuning of fecal control (passive incontinence); (3) Hemorrhoidal cushions: Under normal conditions, these structures provide a fine-tuning seal of the anal canal and can contribute to up to 10%-15% of the overall control[31]. While the basic design is beneficial, deviations from it may quickly flaw their impact, for example if the hemorrhoids either start to protrude or are surgically removed; and (4) Configuration of anal canal: In order to achieve a sufficient closure, the mechanism needs an unhindered ability to generate a strong enough radial force with adequate and concentric pressure values, which are translated to and distributed over a sufficient length of the anal canal (so called high-pressure zone). Altered texture or gross or focal structural deformities of the ano-perineal configuration (e.g., rigid scarring, cloaca, or a keyhole deformity) can be cause to significant symptoms. The latter may result from previous anorectal surgery and - despite a seemingly normal anal pressure profile - may be associated with fecal leakage as capillary forces allow particularly liquid stool components to find their way out (Figure 2). A prolapse of hemorrhoids or the rectum does not only stretch out the sphincter complex and pelvic floor muscles and effectively prevents it from closing the aperture (“shoe in the door”); it also dislocates and everts the crucial sensing zone of the anal canal such that feedback about arriving stool comes too late or not at all.

Figure 2.

Keyhole deformity: After a previous fistulotomy, the anus is not patulous but appears to have a deformity (arrow).

Stool quality and propulsive force

Formed stool is generally easier to control than liquids or gas (even for a perfectly intact anatomy).

Stool load and extent of gas production: An increase in either one is paralleled by a surge of the pressure in the rectum and the resulting force onto the anal canal. Particularly, when the sphincter resistance is weakened, the increased stool load (for example secondary to supplemental fiber intake) induces a higher probability of accidents. Furthermore, increased gas production often results in higher awareness and reduced self-consciousness.

Increased propulsive axial forces: Diarrhea (for example as part of IBS or IBD) not only results in an unfavorable change of the stool consistency but often is associated with a more forceful propulsive wave that further challenges the sphincter complex.

Rectal capacity and compliance (reservoir function)

The normal rectum combines an adequate low-pressure space with the ability of an orderly axial propulsion to allow for accumulation and storage of feces until a coordinated and ideally complete evacuation is desired and effectuated[4]. Parameters that are important in this context include[32]: (1) Rectal capacity: parameter to reflect the overall size of the reservoir whereby a more spacious reservoir allows for storage of more stool, but too large of a reservoir (for example, megarectum or excessive size of a J-pouch) may lead to ineffective evacuation (stool clustering); (2) Rectal compliance: parameter to reflect the distensibility of the rectal wall, i.e., the ratio of Δvolume/Δpressure; and (3) Layout and configuration of the original rectum (e.g., absence of pelvic organ descent and prolapse, kinking, enterocele, rectocele) or of a post-surgical neo-reservoir (e.g., J-pouch vs straight anastomosis).

Pelvic organ descent and prolapse represent a frequent degenerative pathology disproportionally affecting women. The positional instability of the pelvic structures with ineffective initiation and completion of defecation (and/or urine voiding) over time may result in a functionally reduced reservoir and potentially and more frequent and undesired evacuations. It is of note that IBS is characterized by a typically reduced volume tolerance and hence capacity, however in contrast to structural problems the rectal compliance remains normal (increased visceral sensitivity but absence of structural problem)[33]. Last but not least, an impaired reservoir function with decreased size and compliance is commonly seen after previous rectal surgery (e.g., LAR), pelvic radiation, or in the presence of tumors, strictures, or ongoing rectal wall inflammation (IBD, abscess, etc.). Management strategies including surgical efforts to overcome some of these negative impacts by neoadjuvant rather than adjuvant radiation or by creation of a lower pressure reservoir (J-pouch, transverse coloplasty) may result in a short-term benefit with reduced urgency and frequency but in the long run level out and may even be associated with fecal clustering[34].

Neurologic sensory or motor function

Central nervous system: Conscious (awareness) and subconscious networking of information from and to the anorectum are necessary for adequate control. Possible central neurological deficits include focal brain defects from stroke, tumor, trauma, or multiple sclerosis or from more diffuse brain alteration (dementia, multiple sclerosis, infection, drug-induced).

Intact peripheral nerve function: Transmission of the adequate somatic and visceral nerve input to the intestines, as well as the pelvic floor and sphincter muscle complex are needed to allow for correct processing of sensoriceptor information (rectal pressure, sphincter pressure) and pelvic floor function. Peripheral neuropathy may be localized (parity-induced pudendal neuropathy, pelvic radiation, post-surgical), or have a diffuse pattern as a result of diabetes mellitus or neurotoxic drugs such as some chemotherapy agents (e.g., oxaliplatin).

Functional dysfunction: Visceral hypersensitivity is the key concept behind IBS and is characterized by a number of measurable dyssensations (hypersensitivity, spasticity, intensified propulsions) in absence of any morphological correlate.

Symptom analysis

Primary symptoms of fecal incontinence include a worsening lack of control for different rectal components, i.e., solid stool, liquid/semi-formed stool, gas. The degree of content loss is commonly quantitated as staining < soilage < seepage < accidents. Involuntary discharge without any awareness is labeled as passive incontinence, whereas accidents despite awareness and active countermeasures are called urge incontinence. Some patients may report a reduced sensation for arriving stool, a reduced urge-suppressing capacity, and hence a dramatically shortened maximal deferability (“time to bathroom”). It is important to explore and recognize individual variations in relation to other extrinsic factors such as daytime versus nighttime, physical activity, or food intake.

Secondary symptoms of fecal incontinence may develop as a result of leaking stool and include pruritus ani, perianal skin irritation, urinary tract infections, etc. In some patients, these secondary symptoms may in fact be their chief complaint without noticing or acknowledging the lack of control as such.

Depending on the etiology, fecal incontinence may have associated symptoms which need to be actively checked with the patient such as urinary incontinence, vaginal bulging (rectocele, cystocele), prolapse (hemorrhoidal, mucosal, full-thickness rectal), rectovaginal fistula, altered bowel habits.

Workup

A structured workup stands at the beginning of any incontinence management (Table 3). There is a need for a careful, thorough, yet sensitive history in every patient[3,4,10]. The details are necessary to define the complaints and their impact, possible triggering or aggravating factors or events, and the time interval to the onset of symptoms. All past evaluations, treatments with response and failures, as well as the current management and day-to-day routine have to be meticulously explored and documented. Related and seemingly unrelated surgeries such as spinal surgery could be important. Further attention should focus on underlying diseases (diabetes, stroke, chemotherapy), current medications, the dynamics of bowel movements, and associated symptoms. Additional standardized and validated scoring and quality of life instruments are administered to define the severity and impact of the fecal incontinence[4,11,35].

Table 3.

Structured workup of patients with fecal incontinence

| Assessment tool | Details |

| History | Onset |

| Quantitation: staining < soilage < seepage < accidents | |

| Qualitative assessment: passive incontinence vs urge incontinence | |

| Obstetrical history: pregnancies, vaginal deliveries | |

| Previous surgeries: anorectal surgeries, hysterectomy, bladder surgeries, (colo)rectal surgeries, spinal surgeries | |

| Underlying diseases (diabetes, stroke, etc.) | |

| Bowel function and stool quality | |

| Incomplete evacuation | |

| Stool/gas passage through vagina | |

| Medications | |

| Scoring instruments | CCF incontinence score (“Wexner score”) |

| Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life score | |

| Fecal Incontinence Severity Index | |

| St. Marks Incontinence Score | |

| EORTEC SF-36 | |

| Revised Fecal Incontinence Scale | |

| Other scoring instruments | |

| Physical exam | Inspection: patulous anus, folds, perineal body, keyhole, skin irritation, perineal descent, prolapse, cloaca, rectovaginal fistula (stool in vagina)? |

| Digital exam: sphincter integrity, tone (rest/squeeze), compensatory contraction/discoordination, rectocele, mass? | |

| Sensation/anal reflex | |

| Instrumentation/visualization: rule out other pathologies (e.g., rectal tumor, proctitis) | |

| Anophysiology testing | Anal ultrasound |

| Anophysiology testing: | |

| Manometry | |

| Anorectal sensation and volume tolerance | |

| Compliance measurement | |

| Nerve studies: PNTML, occasionally EMG | |

| Placement of SNS trial electrode (phase I) | |

| Additional evaluations in select cases | Imaging: dynamic pelvic MRI |

| Defecating proctogram | |

| Evaluation by other specialties (Urogynecology, Urology, Gastroenterology, etc.) |

The clinical exam includes a visual inspection, an educated digital rectal exam (sphincter integrity, sphincter tone, compensatory auxiliary muscle contraction, length of anal canal, rectocele, palpable mass), as well as at least a limited visualization of the anorectum. A colonic evaluation may not as such contribute to the incontinence management but should be done according to national guidelines to avoid overlooking other more relevant conditions. More objective data can be obtained from anophysiology studies, but the results have to be interpreted with caution in the context of all other factors.

Anophysiology studies attempt to correlate the subjective complaints and clinical exam findings with objective parameters. It would be desirable to define parameters that would directly dictate appropriate respective treatment options and forecast the outcome. However, the predictability of all tests remains a challenge[36]. Furthermore, the value and timing for issuing such tests remain controversial and need to be defined on an individual basis. In recent years since introduction of sacral nerve stimulation, an increasing number of authors have suggested to skip basic testing and in absence of contraindications to proceed with a trial placement of the sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) electrode as the first diagnostic and therapeutic step[37].

Anorectal ultrasound is generally accepted as the most sensitive tool to assess the sphincter complex for the presence or absence of any defect or structural alteration (see Figure 2).

Anal manometry including anorectal sensation and volume tolerance, as well as determination of the rectal compliance aim at objectively assessing the muscle strength and the reservoir function[38-41]. Conventional multichannel manometry has increasingly been replaced by high-resolution manometry using an integrated probe that allows for 3D-analysis and visualization of pressure profiles[42]. A number of reports have correlated clinical symptoms and/or manometry testing with the degree of subjective impairment[43], however it has remained a major challenge to reliably define the best treatment modality or treatment response, respectively[44].

Nerve studies: Measurement of the pudendal nerve conductivity, also known as pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PTNML), is used to identify pudendal neuropathy, which may result from direct or indirect impact (e.g., obstetrical stretch injury, abscess formation, surgery, or radiation) or systemic factors (chemotherapy, diabetes, etc.). The (controversial) parameter has been associated with poor outcomes after overlapping sphincteroplasties in some but not in other studies[45-48]. Electromyography (EMG) aims at analyzing the neuromuscular motor-units, commonly as summary potential by means of painless but imprecise surface electrodes, rarely through precise but very painful needle electrodes. EMG may play a role in confirming paradoxical puborectalis contraction in patients with obstructed defecation, but otherwise is typically of limited value for workup of fecal incontinence.

Depending on the presentation and previous findings, other work-up steps might be appropriate to evaluate more complex pelvic floor dysfunction, e.g., dynamic pelvic MRI, defecating, proctogram, urodynamics, or referral and evaluation by other specialties.

Nonoperative treatment

Management of patients with fecal incontinence invariably starts with non-operative measures. The most pressing goals are (1) to optimize the stool consistency; (2) slow down bowel motility; and (3) to minimize the average stool load in the rectum, particularly prior to leaving the safety of the private home. Specific inflammatory conditions should get the appropriate attention and treatment to correct related diarrhea. Dietary changes are intended to identify and avoid foods that cause diarrhea or urgency. A limited amount of supplementary fibers with limited fluid intake may help to thicken the stool but larger doses tend to unnecessarily increase the stool volumes and may be counterproductive when at the same time the sphincter function is weak. Bowel habit and behavioral training is important to develop regularity while avoiding obsessive patterns. Supportive measures include application of barrier creams to the perianal skin. The stool load may be reduced through rectal washouts (scheduled enemas). Medications are introduced as needed to slow down the bowels (anti-diarrheal medications), bind bile acids (cholestyramine), or to reduce the reflectory sphincter relaxation (antidepressants such as amitriptyline)[49]. There has been speculation about the role of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women[50], but no definitive recommendation has been released.

Physical therapy and biofeedback training aim at strengthening and coordinating the pelvic floor and sphincter function in response to rectal distention, commonly in conjunction with other above mentioned conservative measures[51]. The approach is simple, non-invasive, and without any adverse side effects. Detecting an objective improvement compared to standard care is frequently impossible[52,53], even if the patients report a subjective benefit in 64%-89%[54,55]. In the end, the most significant impact on the patients may be the fact that they are tasked to take an active role in overcoming their incontinence. The use of pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and biofeedback for reconditioning of dysfunctional pelvic floor muscles has long been a conservative fecal incontinence modality. A 2012 Cochrane review of 21 studies with a total of 1525 participants found that a limited number of trials did not provide sufficient evidence for the effectiveness of anal sphincter exercise and biofeedback therapy, but suggested that biofeedback and/or PFMT in combination with other modalities (e.g., electrical nerve stimulation techniques) may enhance the overall outcome. But due to the general weakness of the reported data, the authors concluded that the suggested therapeutic effect of some elements of biofeedback therapy and sphincter exercises was not certain[52].

Operative strategies

Surgical options are explored in patients with significant fecal incontinence that is refractory to conservative management[56]. while avoiding obsessive patterns. Obvious and correctable structural deformities that lend themselves to a surgical intervention should always be addressed first. Examples include a cloaca-like deformity (see Figure 3)[57], hemorrhoidal or full-thickness rectal prolapse, keyhole deformity (after fistulotomy or other surgeries, see Figure 4), or a mucosal ectropion. Other conditions that may emulate the symptom of incontinence (perirectal fistula, rectovaginal fistula) unquestionably should be corrected prior to focusing on the workup or management of the “incontinence” as such[4].

Figure 3.

Anorectal ultrasound showing an anterior defect in external anal sphincter.

Figure 4.

Cloaca-like deformity, corrected with sphincteroplasty and X-flaps.

If gross morphological pathology is either absent or has been corrected, a number of operative approaches strategies are available to address the incontinence itself[8,58]. Their applicability depends on the individual circumstances, the severity of the patient’s symptoms, as well as a clear definition of the treatment goals and priorities[9]. Both the patient and treating physicians need to engage in an optimistic but at the same time honest discussion about the pros and cons, realistic versus unrealistic goals, and the expected outcomes of the various surgeries[3,10]. While this review provides an overview of the concepts (Table 4), a detailed discussion of the techniques and their respective results will be beyond its scope. A task force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, however, has recently reviewed the evidence and published a current status on new technologies[9].

Table 4.

Surgical strategies

| Goal | Options |

| Correction of morphological deformities | Prolapse |

| Cloaca | |

| Keyhole deformity | |

| Perirectal fistula | |

| Rectovaginal fistula | |

| Tumor | |

| Sphincter repair | Overlapping sphincteroplasty |

| Enhancement of impaired sphincter function | Sacral nerve stimulation |

| Radiofrequency energy administration (SECCA™) | |

| Injection of bulking agents (NASHA/DX, beads etc.) | |

| Sphincter replacement/support | Artificial bowel sphincter |

| Implantation of magnetic anal sphincter (Fenix™) | |

| Graciloplasty | |

| Implantation of Thiersch | |

| Implantation of pelvic sling system | |

| Diversion | Colostomy |

| Reduction of fecal load | Malone antegrade continence enema |

Correction of morphological deformities

Reshaping and correction of gross deformities and pathologies (see above).

Sphincter repair

Sphincter repair (sphincteroplasty) seems to be a rational and still probably the most frequently used approach if a segmental sphincter defect is identified (see Figure 2). The goal is to reconstitute the circular configuration of the muscle around the anal canal (see Figure 1) and with that the high pressure zone. The short-term results are generally good with an estimated 75%-86% improvement of incontinence episodes. However, the urgency may persist and over time, the long-term function has been noted to deteriorate with some series reporting only 0%-50% of patients still being fully continent after 5-10 years[59-61]. A systematic review of 16 studies with more than 5 years of follow-up and nearly 900 sphincter repairs noted that most patients remained satisfied with their surgical outcome despite worsening results over time[62].

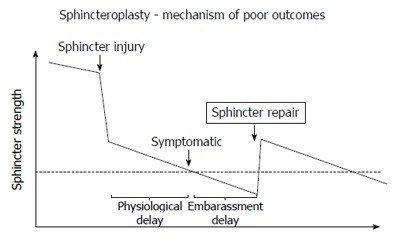

One might speculate that reasons for this unsatisfactory durability are to be found in the fact that the sphincter defect represents a much larger than measurable injury and leads to a faster degeneration process (Figure 5). It will have to be seen whether systematic combination with physical therapy and/or sacral nerve stimulation could result in more durable outcomes of either technique.

Figure 5.

Model for poor outcomes after sphincteroplasty. Hypothetical model to explain poor outcomes after sphincteroplasty: The graph shows a hypothetical time course (x-axis) of the sphincter strength (y-axis) with the dotted line representing the threshold below which incontinence becomes clinically evident. There may be a natural decline of sphincter strength (time before sphincter injury), a dramatic reduction through the injury, followed by an accelerated decline. The physiological delay represents the time until symptoms evolve, while the embarrassment delay reflects the time until a symptomatic patient acknowledges the problem. A sphincter repair may restore some strength, but with continued and possibly accelerated decline of the sphincter function the threshold is again crossed after a period of time.

Enhancement of impaired sphincter function

SNS: This is the concept and surgical modality that - in the last two decades - has transformed the management of fecal incontinence in the most dramatic way. In contrast to other interventions, it does not focus at all on the anal canal as such, and yet, it showed remarkable short- and long-term improvements regardless of whether a sphincter defect was present or not[63]. Prior to being introduced for fecal incontinence, it had been widely utilized for patients with urinary incontinence. In 1995, the first trial for bowel control was reported in Europe and set the starting point for a worldwide revolution[64]. The technique involves two short outpatient procedures under superficial anesthesia. During the first, placement of a 4-point electrode at the sacral root S3 is carried out and linked to a temporary external stimulation device. If the patient shows a good response within the subsequent 2-wk trial period, a definitive implantation of the pacemaker-like stimulator device is performed in the second surgery; otherwise the electrode is removed. Although the exact mechanism of this technique is yet to be completely understood, SNS is believed to re-stimulate a dysfunctional pelvic floor and receptor pathway on one hand and in addition to activate the afferent brain pathway related to the continence mechanism[65,66]. Furthermore, there has been some evidence that it might affect the pacing of the colon and potentially even induce retroperistaltic activity[67]. Independent of the true nature of its effect, the results are fascinating insofar as two thirds of the patients have a greater than 50% improvement such that they have the a definitive stimulator implanted[9]. For the most part, the positive experience is sustained, both immediately and over time. After definitive implantation, 86%-87% of patients reported a greater than 50% improvement and about 40% of the patients achieved perfect control, a success than persisted over 3-5 years and beyond[9,68-70]. The complication rate is relatively low, whereby infection and dislocation of the electrode are the most frequent ones with 3% and 12%, respectively[71]. However, 19%-36% of patients require subsequent interventions for revision or device replacement (battery life)[70,71].

Tibial nerve stimulation: Another related modality of nerve stimulation utilized for the management of fecal incontinence is percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS). Similar to the introduction of SNS, PTNS is a technology that was initially studied and used for the treatment of urinary incontinence[72]. Using either transcutaneous or percutaneous electrodes, the posterior tibial nerve is stimulated in sessions of approximately 30 min duration over a minimum of 3 mo[72]. Although the benefit and mechanism of action of tibial nerve stimulation is even less intuitive and far from being understood, it again is believed to impact fecal control through the activation of the central nervous system and supra-sacral neural centers via the afferent fibers of the peripheral nervous system. As the posterior tibial nerve originates from the ventral branches of lumbar and sacral nerves, it is furthermore believed that a similar response may be elicited as by means of SNS[73].

Radiofrequency energy administration (“SECCA procedure”): This FDA-approved technique involves the delivery of a thermo-controlled multi-point radio-frequency energy (465 kHz) to the depth of the anal canal without burning the mucosal surface. The purpose is to induce an increase of the outlet resistance by means of a controlled scarring; additionally, a remodeling effect on the sphincter muscle fibers has been postulated[9]. Six prospective series and one retrospective study including a United States multicenter trial with 50 patients summarized the results. With the exception of one series (reported on three separate occasions), the majority of reports noted no or only a moderate clinical benefit with 0%-38% of patients achieving more than 50% improvement, but never perfect control[9,74,75].

Injection/implantation of bulking agents: With the goal to bulk up the anal canal or perianal tissues and increase the passive outlet resistance, a number of different techniques have been used to inject or implant a variety of materials (Table 5). Patient selection has been poorly defined but could include those with mild passive incontinence secondary to internal anal sphincter weakness, or patients with postsurgical deformities and an uneven shape of the anal canal. A systematic review on conventional injectables with 16 studies (13 case series, 1 prospective trial with and 2 without data) and a total pool of 420 patients (5-73 patients per study) found little evidence for the effectiveness in passive fecal incontinence; a greater than > 50% improvement was only achieved in 2 studies, while the others reported a 15%-50% improvement at the longest follow-up[76]. Complications and side effects occurred in up to 10% and 12%, respectively[76]. Subsequently, and seemingly for only a limited period of time, NASHA/Dx gained some momentum and was aggressively marketed to specialist physicians and general practitioners alike. The outpatient/office-based injection received attention after in 2011, a prospective randomized, sham-controlled trial of 206 patients in a 2:1 distribution found a greater than 50% improvement in 53.2% vs 30.7% in the intervention versus sham group, respectively[77]. Questions regarding the value of statistical as opposed to clinical significance, a low rate of only 6% complete continence at 6 mo, lack of specific objective data and selection criteria, the durability, and last but not least the cost of the intervention limited the expansion of the technique[9,78,79]. The most recent two strategies that still await broader evaluation include the implantation of self-expandable hyexpan (polyacrylonitrile) prosthesis by means of a applicator gun[80,81], or of stem cells[82,83].

Table 5.

Types of injectable/implantable materials

| Category | Details |

| Conventional | Carbon |

| Teflon or silicon biomaterial beads | |

| Collagen | |

| Autologous fat | |

| Newer | Non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid/dextranomer |

| Pilot | Self-expandable hyexpan (polyacrylonitrile) prosthesis |

| Future | Stem cells |

Sphincter replacement

Dynamic sphincter replacement: (1) Implantation of artificial bowel sphincter: This was the only approach that provided a true functional/dynamic solution with excellent results; its limitations were largely related to the risk of infection (5%) and long-term device erosion or dysfunction[9]. Unfortunately, the device is not on the market anymore; (2) Implantation of magnetic anal sphincter: The aim is to augment the sphincter function by increasing the passive outlet resistance whereby a high enough rectal pressure can overcome the anal canal closure for good or for bad[9]. The method has so far been tested in limited feasibility studies and cases series and shown some promising results[84-86], but prospective data are needed at this point[87]; and (3) Dynamic graciloplasty: The autologous gracilis muscle is carefully mobilized, that is disconnected distally while the proximal neurovascular bundle is preserved. A tunnel is created towards and around the anus and the pedicled muscle wrapped around the anal canal. Unfortunately, the ability to consciously use this muscle and learn voluntary contractions is very limited. However, implantation of a pulse generator device (not available in the United States) for continued electrical stimulation of the muscle induces contractions and over time converts the fast-twitch, fatigable gracilis muscle to a slow-twitch, fatigue-resistant muscle. The technique has been shown to have a reasonable efficacy, but its associated high morbidity has overall limited its use even in countries where such stimulator is available[88,89].

Nondynamic sphincter and pelvic floor support: (1) Thiersch and related procedures: These utilize the placement of an anal encirclement with the aim of narrowing the anal canal and subsequently increase the passive outlet resistance, even when lacking a dynamic component. Both non-elastic and elastic silicone-based implants have been used. The approach is uncommon, and data are anecdotal at best; (2) Non-dynamic graciloplasty or gluteoplasty: The non-stimulated transposition and wrapping of gracilis or gluteus muscle around the anal canal (“bio-Thiersch”) has limited indications because of the high risk of complications and a lack of true functionality. Nonetheless, a retrospective series of 25 patients who underwent unilateral gluteoplasty reported a significant improvement in more than 72%[90]; and (3) Pelvic floor repairs/sling: This fairly old concept of addressing fecal incontinence by correcting the pelvic floor support and restoring the anorectal angle (e.g., posterior Parks repair) was generally unsuccessful. It was hence abandoned, but recently regained some momentum when an investigational trans-obturator posterior anal sling system was introduced and a multi-center trial was launched. A self-fixating poly-propylene mesh is inserted and placed behind the anorectum via two small incisions by means of two curved introducer needles[91]. The trial in 14 United States centers with 152 participants and a 1 year follow-up found that 69.1% of participants met the criteria for treatment success and 19% reported complete continence[92].

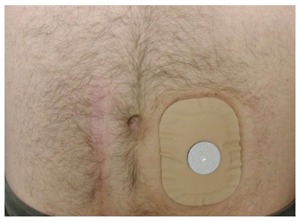

Fecal diversion

When other therapies have failed or when they are preemptively believed to eventually inevitably fail, or if co-morbidities preclude a more aggressive or time-consuming strategy, fecal diversion with the creation of a diverting well-constructed colostomy at a carefully selected site remains a more satisfying than acknowledged alternative[58,93]. Even if it does not restore continence in a strict sense and has an impact on the body image, it provides the patient with the luxury of a controlled waste management and hence permits resumption of a normal personal and social life style. Patients who hesitate prior to the surgery should be encouraged to list pros/cons for both the status quo as well as the creation of a colostomy; to their own surprise, they often realize that objectively the benefits outweigh the negative impacts. It should be noted that some patients are able to train their colostomy such that they can empty their colon with the help of an enema once daily and cover the stoma for the rest of the 24-h cycle (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Trained colostomy. Trained colostomy: After observation of cyclic emptying pattern, in conjunction with appropriate supportive measures (e.g., timed enemas), the patient may not need a true bag, but simply covers the stoma with a mini-appliance with a gas filter.

Rarely used tools

Malone antegrade continence enema: A surgery is performed to create a continent one-way appendicostomy or mini colostomy[94]. The location for that access opening can either be placed into the umbilicus or at a very low cosmetically acceptable location in the right lower quadrant. Alternatively, a percutaneous cecostomy with trap-door button can serve the same purpose. A catheter has to be introduced in scheduled intervals to flush the entire colon and eliminate the fecal load at a time and location chosen by the patient. The concept is attractive in some ways, but the daily irrigation is rather time-consuming and the patients may experience some continued leakage immediately following the irrigation[95].

CONCLUSION

Fecal incontinence is the final common pathway symptom of a variety of conditions, but disproportionally affects woman as a result of gravity and parity. The recognition, workup and treatment remain a huge challenge as the functional aspects do not strictly correlate with the morphological findings[9]. Hence, there is not a single technique that would guarantee perfect outcomes without any morbidities (Table 6). One must assume that successful treatment almost always needs to combine a number of different approaches[56]. Development of a treatment algorithms (e.g., as outlined in the ASCRS position paper) have to be based on the severity of the incontinence, anatomical and functional findings[9,58]. Unquestionable, there is space for expanding our knowledge on all aspects of the control organ[9]. It would be highly desirable to plan and carry out good randomized multi-center trials to study work-up parameters and combination treatments in a standardized and scientific fashion.

Table 6.

Overview of various surgical options with respective outcomes (as detailed in the text)

| Interventions category | Specific technique | Efficacy rate (complete/> 50% improvement) | Complication rates | Grade |

| Correction of morphological abnormalities | Depending on underlying condition: | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Prolapse, cloaca, keyhole deformity, perirectal fistula, rectovaginal fistula, tumor | ||||

| Sphincter repair | Overlapping sphincteroplasty | 75%-85% (short term) | N/A | |

| 0-50% (after 5-10 yr) | ||||

| Enhancement of sphincter function | Sacral nerve stimulation | 0%-56%/51-100% | lead displacement (15%), diarrhea (6%), pain (6-28%), bleeding 11%, infection (3%) | 1B |

| Tibial nerve simulation | 0%-12% (-40%)/0%-67% | 59% (infection, mild gastrodynia, temporary leg numbness) | 2C | |

| Radiofrequency energy administration | 0%/12%-38% (-84%) | 0%-52% (pain, bleeding, infection) | 2B | |

| Injection of: | 0%/33%-90% | 10%-12% (pain, bleeding, infection) | 2A | |

| conventional bulking agents | 6%/56%-61% | |||

| NASHA/DX | ||||

| Sphincter replacement | Artificial bowel sphincter | 61%-90%/31%-100% | 5%-10% infection rates, 30%-52% long-term failure 9 | 1B |

| Implantation of magnetic ring (Fenix™) | NA/54% | 0%-7% obstruction, infection, erosion | 1C | |

| Graciloplasty (dynamic/non-dynamic) | NA/72% | > 40% including urinary tract infection/retention, infections 76 | 2C | |

| Implantation of Thiersch | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Pelvic floor repairs/sling | 19%/69.1% | 17%-30% (pain, infection) | 2C | |

| Fecal diversion | Ileostomy, loop colostomy, end colostomy | near 100% FI improvement | 5%-10% stoma outlet obstruction, stricture, prolapse, hernia | 1C |

| Fecal load reduction | Malone antegrade continence enema | (0%)/33%-100% FI continence | 8%-50% stoma stenosis, leakage | 2C |

Key points

(1) Continence requires a balanced interaction between the anal sphincter complex, the stool consistency, the rectal reservoir function, and neurological function; (2) Fecal incontinence is frequently under-reported, but the estimated prevalence ranges from 0.4%-18%; (3) Management of patients with fecal incontinence starts with a detailed history and physical exam; (4) Symptom severity should be quantified using one of several validated scoring systems, all of which are based on subjective reporting and lack incorporation or correlation with objective test data; (5) Objective evaluation tools include anorectal ultrasound, anal manometry with anorectal sensation and volume tolerance, compliance and strength/reservoir function testing, and nerve studies. Further imaging (e.g., dynamic pelvic MRI, defecating, proctogram), urodynamics, or referral to associated specialties (urology, gynecology) are indicated on an individualized basis; (6) Non-operative management aims at optimizing stool consistency, dietary and bowel habits, as well as muscle function in conjunction with supportive medications and care measures, as well as scheduled enemas to reduce stool load; physical therapy with pelvic floor muscle and biofeedback training are typically encouraged; and (7) Operative strategies are explored in patients with obvious structural deformities or significant fecal incontinence that is refractory to conservative management. Among various available options, the most common ones are sphincter repair, sacral nerve stimulation, sphincter implants, or creation of a stoma.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are not conflicting interests to report.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: September 1, 2016

First decision: September 20, 2016

Article in press: December 8, 2016

P- Reviewer: Awad RA, Chiarioni G, Lakatos PL, Lee JT, Santoro GA S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Wald A. Clinical practice. Fecal incontinence in adults. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1648–1655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp067041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao SS. Diagnosis and management of fecal incontinence. American College of Gastroenterology Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1585–1604. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paquette IM, Varma MG, Kaiser AM, Steele SR, Rafferty JF. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:623–636. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser AM. McGraw-Hill Manual: Colorectal Surgery. 2009. Available from: http://accesssurgery.com/resourceToc.aspx?resourceID=211.

- 5.Xu X, Menees SB, Zochowski MK, Fenner DE. Economic cost of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:586–598. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823dfd6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamm MA. Faecal incontinence. BMJ. 1998;316:528–532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7130.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer I, Richter HE. Impact of fecal incontinence and its treatment on quality of life in women. Womens Health (Lond) 2015;11:225–238. doi: 10.2217/whe.14.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madoff RD. Surgical treatment options for fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:S48–S54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser AM, Orangio GR, Zutshi M, Alva S, Hull TL, Marcello PW, Margolin DA, Rafferty JF, Buie WD, Wexner SD. Current status: new technologies for the treatment of patients with fecal incontinence. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2277–2301. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3464-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alavi K, Chan S, Wise P, Kaiser AM, Sudan R, Bordeianou L. Fecal Incontinence: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1910–1921. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2905-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bharucha AE, Dunivan G, Goode PS, Lukacz ES, Markland AD, Matthews CA, Mott L, Rogers RG, Zinsmeister AR, Whitehead WE, et al. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and classification of fecal incontinence: state of the science summary for the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) workshop. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:127–136. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ditah I, Devaki P, Luma HN, Ditah C, Njei B, Jaiyeoba C, Salami A, Ditah C, Ewelukwa O, Szarka L. Prevalence, trends, and risk factors for fecal incontinence in United States adults, 2005-2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:636–643.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson RL. Epidemiology of fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:S3–S7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faltin DL, Sangalli MR, Curtin F, Morabia A, Weil A. Prevalence of anal incontinence and other anorectal symptoms in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12:117–120; discussion 121. doi: 10.1007/pl00004031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johanson JF, Lafferty J. Epidemiology of fecal incontinence: the silent affliction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson R, Norton N, Cautley E, Furner S. Community-based prevalence of anal incontinence. JAMA. 1995;274:559–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson R, Furner S, Jesudason V. Fecal incontinence in Wisconsin nursing homes: prevalence and associations. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1226–1229. doi: 10.1007/BF02258218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu JM, Matthews CA, Vaughan CP, Markland AD. Urinary, fecal, and dual incontinence in older U.S. Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:947–953. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jerez-Roig J, Souza DL, Amaral FL, Lima KC. Prevalence of fecal incontinence (FI) and associated factors in institutionalized older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrews CN, Bharucha AE. The etiology, assessment, and treatment of fecal incontinence. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:516–525. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin GH, Toto EL, Schey R. Pregnancy and postpartum bowel changes: constipation and fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:521–529; quiz 530. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ternent CA, Fleming F, Welton ML, Buie WD, Steele S, Rafferty J. Clinical Practice Guideline for Ambulatory Anorectal Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:915–922. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallenhorst T, Bouguen G, Brochard C, Cunin D, Desfourneaux V, Ropert A, Bretagne JF, Siproudhis L. Long-term impact of full-thickness rectal prolapse treatment on fecal incontinence. Surgery. 2015;158:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markland AD, Dunivan GC, Vaughan CP, Rogers RG. Anal Intercourse and Fecal Incontinence: Evidence from the 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:269–274. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walma MS, Kornmann VN, Boerma D, de Roos MA, van Westreenen HL. Predictors of fecal incontinence and related quality of life after a total mesorectal excision with primary anastomosis for patients with rectal cancer. Ann Coloproctol. 2015;31:23–28. doi: 10.3393/ac.2015.31.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Handa VL, Blomquist JL, McDermott KC, Friedman S, Muñoz A. Pelvic floor disorders after vaginal birth: effect of episiotomy, perineal laceration, and operative birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:233–239. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318240df4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000081.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaiser AM, Ortega AE. Anorectal anatomy. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82:1125–1138, v. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(02)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lestar B, Penninckx F, Kerremans R. The composition of anal basal pressure. An in vivo and in vitro study in man. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:118–122. doi: 10.1007/BF01646870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felt-Bersma RJ, Sloots CE, Poen AC, Cuesta MA, Meuwissen SG. Rectal compliance as a routine measurement: extreme volumes have direct clinical impact and normal volumes exclude rectum as a problem. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1732–1738. doi: 10.1007/BF02236859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zar S, Benson MJ, Kumar D. Rectal afferent hypersensitivity and compliance in irritable bowel syndrome: differences between diarrhoea-predominant and constipation-predominant subgroups. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:151–158. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200602000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fazio VW, Zutshi M, Remzi FH, Parc Y, Ruppert R, Fürst A, Celebrezze J, Galanduik S, Orangio G, Hyman N, et al. A randomized multicenter trial to compare long-term functional outcome, quality of life, and complications of surgical procedures for low rectal cancers. Ann Surg. 2007;246:481–488; discussion 488-490. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181485617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaizey CJ. Faecal incontinence: standardizing outcome measures. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:156–158. doi: 10.1111/codi.12566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quezada Y, Whiteside JL, Rice T, Karram M, Rafferty JF, Paquette IM. Does preoperative anal physiology testing or ultrasonography predict clinical outcome with sacral neuromodulation for fecal incontinence? Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1613–1617. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2746-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maeda Y, O’Connell PR, Lehur PA, Matzel KE, Laurberg S. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence and constipation: a European consensus statement. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:O74–O87. doi: 10.1111/codi.12905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gooneratne ML, Scott SM, Lunniss PJ. Unilateral pudendal neuropathy is common in patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:449–458. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0839-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fitzpatrick M, O’brien C, O’connell PR, O’herlihy C. Patterns of abnormal pudendal nerve function that are associated with postpartum fecal incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:730–735. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00817-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Súilleabháin CB, Horgan AF, McEnroe L, Poon FW, Anderson JH, Finlay IG, McKee RF. The relationship of pudendal nerve terminal motor latency to squeeze pressure in patients with idiopathic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:666–671. doi: 10.1007/BF02234563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasmussen OO, Christiansen J, Tetzschner T, Sørensen M. Pudendal nerve function in idiopathic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:633–636; discussion 636-637. doi: 10.1007/BF02235577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soh JS, Lee HJ, Jung KW, Yoon IJ, Koo HS, Seo SY, Lee S, Bae JH, Lee HS, Park SH, et al. The diagnostic value of a digital rectal examination compared with high-resolution anorectal manometry in patients with chronic constipation and fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1197–1204. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zutshi M, Salcedo L, Hammel J, Hull T. Anal physiology testing in fecal incontinence: is it of any value? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:277–282. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0830-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pehl C, Seidl H, Scalercio N, Gundling F, Schmidt T, Schepp W, Labermeyer S. Accuracy of anorectal manometry in patients with fecal incontinence. Digestion. 2012;86:78–85. doi: 10.1159/000338954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilliland R, Altomare DF, Moreira H, Oliveira L, Gilliland JE, Wexner SD. Pudendal neuropathy is predictive of failure following anterior overlapping sphincteroplasty. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1516–1522. doi: 10.1007/BF02237299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen AS, Luchtefeld MA, Senagore AJ, Mackeigan JM, Hoyt C. Pudendal nerve latency. Does it predict outcome of anal sphincter repair? Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1005–1009. doi: 10.1007/BF02237391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sangwan YP, Coller JA, Barrett RC, Roberts PL, Murray JJ, Rusin L, Schoetz DJ. Unilateral pudendal neuropathy. Impact on outcome of anal sphincter repair. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:686–689. doi: 10.1007/BF02056951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buie WD, Lowry AC, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD. Clinical rather than laboratory assessment predicts continence after anterior sphincteroplasty. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1255–1260. doi: 10.1007/BF02234781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santoro GA, Eitan BZ, Pryde A, Bartolo DC. Open study of low-dose amitriptyline in the treatment of patients with idiopathic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1676–1681; discussion 1681-1682. doi: 10.1007/BF02236848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melville JL, Newton K, Fan MY, Katon W. Health care discussions and treatment for urinary incontinence in U.S. women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sjödahl J, Walter SA, Johansson E, Ingemansson A, Ryn AK, Hallböök O. Combination therapy with biofeedback, loperamide, and stool-bulking agents is effective for the treatment of fecal incontinence in women - a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:965–974. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.999252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norton C, Cody JD. Biofeedback and/or sphincter exercises for the treatment of faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002111. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002111.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Norton C, Chelvanayagam S, Wilson-Barnett J, Redfern S, Kamm MA. Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback for fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiarioni G, Bassotti G, Stanganini S, Vantini I, Whitehead WE. Sensory retraining is key to biofeedback therapy for formed stool fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:109–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lacima G, Pera M, Amador A, Escaramís G, Piqué JM. Long-term results of biofeedback treatment for faecal incontinence: a comparative study with untreated controls. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:742–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown SR, Wadhawan H, Nelson RL. Surgery for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD001757. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001757.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaiser AM. Cloaca-like deformity with faecal incontinence after severe obstetric injury--technique and functional outcome of ano-vaginal and perineal reconstruction with X-flaps and sphincteroplasty. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:827–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Madoff RD, Parker SC, Varma MG, Lowry AC. Faecal incontinence in adults. Lancet. 2004;364:621–632. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16856-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson E, Carlsen E, Steen TB, Backer Hjorthaug JO, Eriksen MT, Johannessen HO. Short- and long-term results of secondary anterior sphincteroplasty in 33 patients with obstetric injury. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1466–1472. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.519019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zutshi M, Tracey TH, Bast J, Halverson A, Na J. Ten-year outcome after anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1089–1094. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a0a79c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rothbarth J, Bemelman WA, Meijerink WJ, Buyze-Westerweel ME, van Dijk JG, Delemarre JB. Long-term results of anterior anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence due to obstetric injury / with invited commentaries. Dig Surg. 2000;17:390–393; discussion 394. doi: 10.1159/000018883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glasgow SC, Lowry AC. Long-term outcomes of anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:482–490. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182468c22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ratto C, Litta F, Parello A, Donisi L, De Simone V, Zaccone G. Sacral nerve stimulation in faecal incontinence associated with an anal sphincter lesion: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e297–e304. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matzel KE, Stadelmaier U, Hohenfellner M, Gall FP. Electrical stimulation of sacral spinal nerves for treatment of faecal incontinence. Lancet. 1995;346:1124–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91799-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lundby L, Møller A, Buntzen S, Krogh K, Vang K, Gjedde A, Laurberg S. Relief of fecal incontinence by sacral nerve stimulation linked to focal brain activation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:318–323. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31820348ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Michelsen HB, Thompson-Fawcett M, Lundby L, Krogh K, Laurberg S, Buntzen S. Six years of experience with sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:414–421. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181ca7dc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patton V, Wiklendt L, Arkwright JW, Lubowski DZ, Dinning PG. The effect of sacral nerve stimulation on distal colonic motility in patients with faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2013;100:959–968. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wexner SD, Coller JA, Devroede G, Hull T, McCallum R, Chan M, Ayscue JM, Shobeiri AS, Margolin D, England M, et al. Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence: results of a 120-patient prospective multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:441–449. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181cf8ed0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mellgren A, Wexner SD, Coller JA, Devroede G, Lerew DR, Madoff RD, Hull T. Long-term efficacy and safety of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1065–1075. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822155e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hull T, Giese C, Wexner SD, Mellgren A, Devroede G, Madoff RD, Stromberg K, Coller JA. Long-term durability of sacral nerve stimulation therapy for chronic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:234–245. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318276b24c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Duelund-Jakobsen J, Lehur PA, Lundby L, Wyart V, Laurberg S, Buntzen S. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence - efficacy confirmed from a two-centre prospectively maintained database. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:421–428. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wexner SD, Bleier J. Current surgical strategies to treat fecal incontinence. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:1577–1589. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1093417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peña Ros E, Parra Baños PA, Benavides Buleje JA, Muñoz Camarena JM, Escamilla Segade C, Candel Arenas MF, Gonzalez Valverde FM, Albarracín Marín-Blázquez A. Short-term outcome of percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) for the treatment of faecal incontinence. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20:19–24. doi: 10.1007/s10151-015-1380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Efron JE, Corman ML, Fleshman J, Barnett J, Nagle D, Birnbaum E, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Sligh S, Rabine J, et al. Safety and effectiveness of temperature-controlled radio-frequency energy delivery to the anal canal (Secca procedure) for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1606–1616; discussion 1616-1618. doi: 10.1007/BF02660763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abbas MA, Tam MS, Chun LJ. Radiofrequency treatment for fecal incontinence: is it effective long-term? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:605–610. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182415406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Luo C, Samaranayake CB, Plank LD, Bissett IP. Systematic review on the efficacy and safety of injectable bulking agents for passive faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:296–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Graf W, Mellgren A, Matzel KE, Hull T, Johansson C, Bernstein M. Efficacy of dextranomer in stabilised hyaluronic acid for treatment of faecal incontinence: a randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maeda Y, Laurberg S, Norton C. Perianal injectable bulking agents as treatment for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2):CD007959. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007959.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wald A. New treatments for fecal incontinence: update for the gastroenterologist. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1783–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ratto C, Donisi L, Litta F, Campennì P, Parello A. Implantation of SphinKeeper(TM): a new artificial anal sphincter. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s10151-015-1396-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ratto C, Buntzen S, Aigner F, Altomare DF, Heydari A, Donisi L, Lundby L, Parello A. Multicentre observational study of the Gatekeeper for faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2016;103:290–299. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Salcedo L, Sopko N, Jiang HH, Damaser M, Penn M, Zutshi M. Chemokine upregulation in response to anal sphincter and pudendal nerve injury: potential signals for stem cell homing. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1577–1581. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lane FL, Jacobs SA, Craig JB, Nistor G, Markle D, Noblett KL, Osann K, Keirstead H. In vivo recovery of the injured anal sphincter after repair and injection of myogenic stem cells: an experimental model. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1290–1297. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a4adfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lehur PA, McNevin S, Buntzen S, Mellgren AF, Laurberg S, Madoff RD. Magnetic anal sphincter augmentation for the treatment of fecal incontinence: a preliminary report from a feasibility study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1604–1610. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f5d5f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barussaud ML, Mantoo S, Wyart V, Meurette G, Lehur PA. The magnetic anal sphincter in faecal incontinence: is initial success sustained over time? Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1499–1503. doi: 10.1111/codi.12423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pakravan F, Helmes C. Magnetic anal sphincter augmentation in patients with severe fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:109–114. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lehur PA, Wyart V, Riche VP. SaFaRI: sacral nerve stimulation versus the Fenix® magnetic sphincter augmentation for adult faecal incontinence: a randomised investigation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:1505. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2531-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Matzel KE, Madoff RD, LaFontaine LJ, Baeten CG, Buie WD, Christiansen J, Wexner S. Complications of dynamic graciloplasty: incidence, management, and impact on outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1427–1435. doi: 10.1007/BF02234593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rongen MJ, Uludag O, El Naggar K, Geerdes BP, Konsten J, Baeten CG. Long-term follow-up of dynamic graciloplasty for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:716–721. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hultman CS, Zenn MR, Agarwal T, Baker CC. Restoration of fecal continence after functional gluteoplasty: long-term results, technical refinements, and donor-site morbidity. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:65–70; discussion 70-71. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000186513.75052.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rosenblatt P. New developments in therapies for fecal incontinence. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27:353–358. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mellgren A, Zutshi M, Lucente VR, Culligan P, Fenner DE. A posterior anal sling for fecal incontinence: results of a 152-patient prospective multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:349.e1–349.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hendren S, Hammond K, Glasgow SC, Perry WB, Buie WD, Steele SR, Rafferty J. Clinical practice guidelines for ostomy surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:375–387. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Patel AS, Saratzis A, Arasaradnam R, Harmston C. Use of Antegrade Continence Enema for the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence and Functional Constipation in Adults: A Systematic Review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:999–1013. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koch SM, Uludağ O, El Naggar K, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG. Colonic irrigation for defecation disorders after dynamic graciloplasty. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0375-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]