Abstract

AIM

To evaluate whether repeated serum measurements of trefoil factor-3 (TFF-3) can reliably reflect mucosal healing (MH) in Crohn’s disease (CD) patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (anti-TNF-α) antibodies.

METHODS

Serum TFF-3 was measured before and after anti-TNF-α induction therapy in 30 CD patients. The results were related to clinical, biochemical and endoscopic parameters. MH was defined as a ≥ 50% decrease in Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease (SES-CD).

RESULTS

SES-CD correlated significantly with CD clinical activity and several standard biochemical parameters (albumin, leukocyte and platelet counts, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fibrinogen). In contrast, SES-CD did not correlate with TFF-3 (P = 0.54). Moreover, TFF-3 levels did not change significantly after therapy irrespectively of whether the patients achieved MH or not. Likewise, TFF-3 did not correlate with changes in fecal calprotectin, which has been proposed as another biochemical marker of mucosal damage in CD.

CONCLUSION

Serum TFF-3 is not a convenient and reliable surrogate marker of MH during therapy with TNF-α antagonists in CD.

Keywords: Adalimumab, Crohn’s disease, Infliximab, Mucosal healing, Trefoil factors

Core tip: Mucosal healing (MH) is viewed as the holy grail of the efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (anti-TNF-α) therapy for Crohn’s disease (CD), however performance of repeated colonoscopies is questionable for economical and safety reasons. We aimed to assess, whether serum trefoil factor-3 (TFF-3), a parameter engaged in maintaining mucosal integrity, could be useful in the assessment of MH. We found no correlation between TFF-3 and CD endoscopic activity and fecal calprotectin. Changes in TFF-3 did not reflect the degree to which MH was achieved. Thus, TFF-3 does not seem to be a reliable surrogate marker for MH in CD patients undergoing anti-TNF-α therapy.

INTRODUCTION

A great deal of data shows that mucosal healing (MH) is the most sensitive marker of successful outcome of therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-α) antibodies for Crohn’s disease (CD)[1]. These drugs have the greatest potential to induce MH when compared with other pharmacological agents[2]. It has been suggested that the occurrence of MH after anti-TNF-α therapy predicts successful long-term clinical remission and lower hospitalization and surgery rates[3]. There are, however, difficulties in rigorous and practical defining MH[4,5]. In this respect, repeated endoscopy seems to be the most appropriate method, however, its use may be limited by the associated invasiveness and costs[5]. Therefore, there is a need for new parameters that are simple and cheap to monitor reliably MH during anti-TNF-α therapy in CD.

Trefoil factors (TFFs) are a family of mucin-associated peptides secreted by goblet cells in the intestinal epithelium. They play an important role in maintaining mucosal barrier integrity[6]. It has recently been suggested that serum levels of TFF-3 can reflect MH in ulcerative colitis (UC)[7]. There are, however, no data on whether TFF-3 can play a similar role in CD.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the usefulness of repeated serum TFF-3 measurements for the assessment of MH in CD patients treated with anti-TNF-α antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients with diagnosed CD were prospectively enrolled to the analysis. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) failure of standard pharmacological treatment for CD according to current guidelines[8] in patients with Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) ≥ 300 points or with active perianal lesions; and (2) full ileocolonoscopy with the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) assessment[5].

For the induction therapy the patients received either infliximab (IFX; 5 mg/kg body weight intravenously at 0-2-6 wk) or adalimumab (ADA; 160 mg at week 0, 80 mg at week 2 and 40 mg every other week subcutaneously till week 12). Patients underwent clinical, biochemical, and endoscopic assessment at week 10 (IFX) or at week 14 (ADA). MH was defined as at least a 50% decrease in SES-CD (endoscopic criterion)[5]. Clinical response to therapy was defined as a decrease in CDAI by at least 100 points[9].

In addition, in some patients, fecal calprotectin (FC) was measured using PhiCal® Calprotectin ELISA (Immundiagnostik, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, as FC is believed to be the most useful surrogate marker of endoscopic activity in CD[10].

Serum concentrations of TFF-3 were measured using DuoSet® Immunoassay kit (R&D Systems, United States), as per manufacturer’s instructions in parallel with clinical and endoscopic assessment before (week 0) and after the induction anti-TNF-α therapy (week 10 for IFX and week 14 for ADA). Patients who required any change in the concomitant treatment during the induction anti-TNF-α therapy were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were checked for the normality of distribution. As the data did not display consistently normal distribution, they were analyzed using non-parametric statistics for paired (the Wilcoxon test) or unpaired (the Mann-Whitney U test) data, as appropriate. Categorized data were assessed with the Fisher’s exact test. Correlations were assessed with the use of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. All data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 6.07 (GraphPad Software Inc., United States).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences (No. 409/2013). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

RESULTS

Patients characteristics

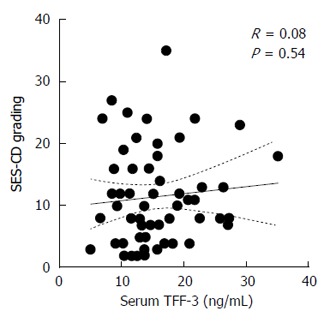

A total of 30 patients were enrolled, with one patient being excluded from the analysis owing to the incompleteness of biochemical data. Firstly we correlated SES-CD scores recorded before and after therapy with TFF-3 levels at the same time points (Figure 1). It turned out that absolute TFF-3 concentrations in serum did not correlate with the status of the mucosa as assessed by endoscopy. In sharp contrast, SES-CD correlated significantly with other parameters proposed as surrogate markers of severity of the disease (Table 1). In particular, SES-CD correlated well - in a positive and negative manner, respectively - with an index of clinical activity of the disease (CDAI) and albumin levels. Other significant correlations included leukocyte and platelet counts, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and fibrinogen. These observations indicated that the population of CD patients analyzed exhibited typical and expected responses to anti-TNF-α treatment[11].

Figure 1.

Correlation of serum trefoil factor-3 concentrations with Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease scores. Samples were collected from 29 patients before and after the induction therapy with anti-TNF-α agents (n = 58). TFF-3: Trefoil factor-3; SES-CD: Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease.

Table 1.

Correlation of Crohn’s disease endoscopic activity assessed by Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease with clinical and biochemical parameters recorded at the same time

|

Simple endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease vs biochemical parameters |

|||||||||

| CDAI | Albumin | WBC | PLT | CRP | Hb | Ferritin | Fibrinogen | ESR | |

| R value | 0.66 | -0.62 | 0.3500 | 0.4400 | 0.57 | -0.40 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 0.57 |

| P value | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0071 | 0.0005 | < 0.0001 | 0.0018 | 0.41 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

Endoscopy was performed in 29 patients before and after the induction therapy with anti-TNF-α agents (n = 58). CDAI: Crohn’s Disease Activity Index; WBC: White blood count; PLT: Platelets; CRP: C-reactive protein; Hb: Hemoglobin; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; SES-CD: Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn's Disease.

Secondly in the next step, we analyzed changes in serum TFF-3 in patients with or without MH in response to therapy. To this end the patients were stratified according to the magnitude of decrease in SES-CD (with values ≥ 50% and < 50% corresponding to successful and unsuccessful MH, respectively)[5].

Full clinical and demographic patient characteristics at baseline is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical, biochemical and demographic characteristics of Crohn’s disease patients with or without successful mucosal healing in response to anti-TNF-α therapy n (%)

| Feature | All (n = 29) | MH-group (n = 18) | Non-MH group (n = 11) | MH vs non-MH |

| Change in Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease over time (%) | -55 [-72-(-37)] | -70 [-81-(-56)] | -33 [-38-(-8)] | P < 0.0001 |

| Age (yr) | 27 (21-35) | 22 (21-30) | 35 (27-39) | P = 0.02 |

| Men | 21 (72) | 15 (83) | 5 (45) | P = 0.04 |

| Disease duration (yr) | 6 (3-11) | 6 (5-10) | 6 (3-12) | P = 0.77 |

| Baseline Crohn’s disease Activity Index (n) | 319 (298-420) | 310 (240-397) | 348 (301-440) | P = 0.26 |

| Baseline Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease (n) | 15 (8-21) | 16 (8-23) | 12 (8-20) | P = 0.36 |

| Baseline C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 9.8 (2.8-31.2) | 8.7 (2.3-18.2) | 18.6 (3.7-34.5) | P = 0.15 |

| Baseline hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.9 (10.1-14) | 12 (9.9-13.5) | 13.1 (10.2-14.8) | P = 0.60 |

| Baseline albumin (mg/dL) | 4.2 (3.6-4.4) | 4.1 (3.5-4.4) | 4.2 (3.7-4.4) | P = 0.84 |

| Disease location | ||||

| L1 (ileal) | 3/29 (10) | 1/18 (5) | 2/11 (18) | P = 0.53 |

| L2 (colonic) | 9/29 (31) | 5/18 (28) | 4/11 (36) | P = 0.69 |

| L3 (ileocolonic) | 17/29 (59) | 12/18 (67) | 5/11 (46) | P = 0.43 |

| Disease behavior | ||||

| B1 (inflammatory) | 24/29 (83) | 14/18 (78) | 10/11 (91) | P = 0.62 |

| B2 (stricturing) | 1/29 (3) | 1/18 (5) | 0/11 (0) | P = 1.00 |

| B3 (penetrating) | 4/29 (14) | 3/18 (17) | 1/11 (9) | P = 1.00 |

| Medications | ||||

| Steroids | 19/29 (65) | 10/18 (55) | 9/11 (82) | P = 0.23 |

| Azathioprine | 15/29 (52) | 12/18 (67) | 3/11 (27) | P = 0.06 |

| Aminosalicylates | 28/29 (96) | 18/18 (100) | 10/11 (91) | P = 0.37 |

| Anti-TNF-α agent used: adalimumab/infliximab | 17/12 (59/41) | 11/7 (61/39) | 6/5 (55/45) | P = 0.51 |

The data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges. MH: Mucosal healing.

According to these criteria 18 out of 29 patients (62%) achieved successful MH. Baseline analysis revealed that patients with MH were younger and more often male (Table 2). Other parameters, including the indexes of clinical and endoscopic activity of the disease and several conventional biochemical markers did not differ between patients with and without MH. There was also no formal difference between the groups in TFF-3 levels both before and after the intervention (Figure 2). Comparison of TFF-3 levels before and after therapy separately for each group revealed no significant difference in patients with MH [(median and IQR): 13.50 (9.25-18.36) ng/mL vs 13.68 (12.33-17.26) ng/mL]. TFF-3 concentrations in patients with no MH tended to increase slightly over time [(median and IQR): 14.63 (10.98-19.02) vs 17.74 (13.34-22.53) ng/mL]. However, the effect was neither significant nor consistent (Figure 2). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in TFF-3 changes expressed in either absolute or relative values. Moreover, the magnitude of changes in TFF-3 did not correlate with changes in CD clinical activity (not shown).

Figure 2.

Individual changes in serum trefoil factor-3 during anti-TNF-α therapy in patients with or without successful mucosal healing as assessed by endoscopy. MH: Mucosal healing; TFF-3: Trefoil factor-3.

Fecal calprotectin

In 10 patients from the study group the endoscopic assessment of the gut was coupled with the measurement of FC before and after therapy. The levels of FC were found to correlate only weakly with SES-CD (R = 0.38) and did not correlate at all with serum TFF-3 (Figure 3). Moreover, changes in TFF-3 levels over the course of therapy were not reflected by corresponding changes in FC (not shown).

Figure 3.

Correlation of fecal calprotectin with Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease and serum trefoil factor-3 in 10 patients assessed before and after the induction therapy with anti-TNF-α agents (n = 20). TFF-3: Trefoil factor-3; SES-CD: Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; FC: Fecal calprotectin.

DISCUSSION

Anti-TNF-α therapy is used more and more frequently and at earlier stages of CD. There is however an ongoing debate on how to best monitor its efficacy and what should be its main therapeutic goal[12]. While MH is increasingly viewed as the best predictor of short- and long-term prognosis, it is not clear whether endoscopic assessment of MH could be replaced by any biochemical surrogate marker that is more convenient to apply in everyday clinical practice[4,5]. As a factor that plays an important role in maintaining the integrity of intestinal mucosa, TFF-3 could be considered as a potential candidate. TFF-3 is induced by mucosal injury and acts to promote epithelial repair[6]. Although, increased expression of TFF-3 in the inflamed mucosa was shown both in human IBD and in animal studies, it is not certain if this reflects IBD activity[7]. There are only limited data on TFF-3 in UC, and no data at all on its role in CD[6,7,13]. Srivastava et al[7] have recently demonstrated that median serum TFF-3 concentration in UC patients without MH was significantly higher than that in patients with MH and healthy controls. Our study was the first ever attempt to assess changes in TFF-3 in patients with CD treated with biological agents.

While our analysis confirmed that there is a need for new markers of CD activity (as significant improvement in several clinical and biochemical parameters occurred also in some patients without appreciable MH), it failed to demonstrate that TFF-3 could serve reliably as such a marker.

Firstly, TFF-3 concentrations did not correspond to the status of the mucosa as assessed by SES-CD. Secondly, the direction and the extent of intestinal changes in response to therapy did not correlate well with changes in serum TFF-3. Although the average levels of TFF-3 seemed to increase over time in patients with unsuccessful MH, such increases in TFF-3 did also occur in some patients with clear endoscopic improvement. Conversely, some patients with unsuccessful MH experienced a decrease in TFF-3. Thirdly, TFF-3 levels did not correlate with the levels of FC. To date, FC has been viewed as the most promising new biomarker of the mucosal status, despite the fact that the disease location can significantly impact on how well FC correlates with MH[14-16]. Indeed, we have observed only weak-to-moderate correlation between FC with SES-CD in our group of patients. However, we could not detect any significant correlation between FC and TFF-3.

Our study has several limitations including a single centre design and a relatively small sample size. The latter was primarily related to a limited number of patients on whom repeated colonoscopic examination could be performed in a short period of time. Another issue was how to define MH, as different algorithms are in use. The criteria ultimately applied were strictly in accordance with the latest recommendations by the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease[5]. It is also a matter of debate when to assess MH in CD for the first time. There are different algorithms, however - taking into account that current guidelines define anti-TNF-α induction regimen as 7 doses of ADA or 3 doses of IFX - in the majority of trials MH was initially estimated between week 10-14 and at week 12-14 in case of IFX or ADA, respectively[8,11,17].

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge this is the first ever study undertaken to assess the usefulness of serum TFF-3 for MH monitoring in CD patients treated with anti-TNF-α antibodies. While our observations should be validated in independent and larger cohorts of patients, they do not support the hypothesis that serum TFF-3 levels alone could serve as a convenient and reliable surrogate marker of MH during therapy with TNF-α antagonists in CD.

COMMENTS

Background

Mucosal healing (MH) is one of the most important goals of anti-TNF-α therapy for Crohn’s disease (CD), because it predicts successful long-term clinical remission and lower hospitalization and surgery rates. It is crucial to find new non-invasive parameters that could reliably reflect MH, since repeated colonoscopies are problematic for both economical and safety reasons.

Research frontiers

MH is hot topic in the field of therapeutic monitoring in CD, especially during anti-TNF-α therapy, since TNF-α inhibitors have the highest potential to induce MH.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Trefoil factor-3 (TFF-3) is a mucin-associated peptide involved in the maintenance of intestinal mucosal integrity. It was hypothesized that TFF-3 can serve as a marker of MH in ulcerative colitis. Here, we have analyzed for the first time whether TFF-3 could be useful for monitoring MH in the course of anti-TNF-α therapy for CD.

Applications

The current study shows that serum TFF-3 is not a reliable surrogate marker of MH in CD patients treated with anti-TNF-α agents.

Terminology

Mucosal healing - reduction or disappearance of erosions and ulcerations in inflammatory bowel disease as a result of treatment. It predicts long-term clinical remission and fewer complications in the course of CD.

Peer-review

The authors present the results of a prospective study of the utility of measuring serum TFF-3 in patients with CD for predicting mucosal healing following induction therapy with anti-TNF agents. The results are clearly presented and will be of interest, if only because they offer a clear message that TFF-3 performs poorly as a biomarker of mucosal healing in CD.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Poland

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences (No. 409/2013).

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Conflict-of-interest statement: Eder P received lecture fees from Abbvie Poland and travel grants from Astellas and Abbvie Poland; Lykowska-Szuber L received travel grants from Alvogen and Abbvie Poland. Krela-Kazmierczak I received travel grants from Alvogen and Astellas. Linke K received travel grant from Abbvie Poland. Korybalska K, Stawczyk-Eder K, Czepulis N, Luczak J and Witowski J have nothing to disclose.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: July 22, 2016

First decision: October 20, 2016

Article in press: November 28, 2016

P- Reviewer: Can G, Doherty GA S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Antunes O, Filippi J, Hébuterne X, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Treatment algorithms in Crohn’s - up, down or something else? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61:1619–1635. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pineton de Chambrun G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lémann M, Colombel JF. Clinical implications of mucosal healing for the management of IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:15–29. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogler G, Vavricka S, Schoepfer A, Lakatos PL. Mucosal healing and deep remission: what does it mean? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7552–7560. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vuitton L, Marteau P, Sandborn WJ, Levesque BG, Feagan B, Vermeire S, Danese S, D’Haens G, Lowenberg M, Khanna R, et al. IOIBD technical review on endoscopic indices for Crohn’s disease clinical trials. Gut. 2016;65:1447–1455. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aamann L, Vestergaard EM, Gronbaek H. Trefoil factors in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3223–3230. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srivastava S, Kedia S, Kumar S, Pratap Mouli V, Dhingra R, Sachdev V, Tiwari V, Kurrey L, Pradhan R, Ahuja V. Serum human trefoil factor 3 is a biomarker for mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis patients with minimal disease activity. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:575–579. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Lémann M, Söderholm J, Colombel JF, Danese S, D’Hoore A, Gassull M, Gomollón F, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28–62. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levesque BG, Sandborn WJ, Ruel J, Feagan BG, Sands BE, Colombel JF. Converging goals of treatment of inflammatory bowel disease from clinical trials and practice. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:37–51.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsham NE, Sherwood RA. Fecal calprotectin in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:21–29. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S51902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben-Horin S, Mao R, Chen M. Optimizing biologic treatment in IBD: objective measures, but when, how and how often? BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:178. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0408-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danese S, Vuitton L, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Biologic agents for IBD: practical insights. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:537–545. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grønbaek H, Vestergaard EM, Hey H, Nielsen JN, Nexø E. Serum trefoil factors in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 2006;74:33–39. doi: 10.1159/000096591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stawczyk-Eder K, Eder P, Lykowska-Szuber L, Krela-Kazmierczak I, Klimczak K, Szymczak A, Szachta P, Katulska K, Linke K. Is faecal calprotectin equally useful in all Crohn’s disease locations? A prospective, comparative study. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:353–361. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.43672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang S, Malter L, Hudesman D. Disease monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11246–11259. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i40.11246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gecse KB, Brandse JF, van Wilpe S, Löwenberg M, Ponsioen C, van den Brink G, D’Haens G. Impact of disease location on fecal calprotectin levels in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:841–847. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1008035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dave M, Loftus EV. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease-a true paradigm of success? Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2012;8:29–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]