Abstract

Our understanding of staphylococcal pathogenesis depends on reliable genetic tools for gene expression analysis and tracing of bacteria. Here, we have developed and evaluated a series of novel versatile Escherichia coli-staphylococcal shuttle vectors based on PCR-generated interchangeable cassettes. Advantages of our module system include the use of (i) staphylococcal low-copy-number, high-copy-number, thermosensitive and theta replicons and selectable markers (choice of erythromycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, or spectinomycin); (ii) an E. coli replicon and selectable marker (ampicillin); and (iii) a staphylococcal phage fragment that allows high-frequency transduction and an SaPI fragment that allows site-specific integration into the Staphylococcus aureus chromosome. The staphylococcal cadmium-inducible Pcad-cadC and constitutive PblaZ promoters were designed and analyzed in transcriptional fusions to the staphylococcal β-lactamase blaZ, the Vibrio fischeri luxAB, and the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein reporter genes. The modular design of the vector system provides great flexibility and variety. Questions about gene dosage, complementation, and cis-trans effects can now be conveniently addressed, so that this system constitutes an effective tool for studying gene regulation of staphylococci in various ecosystems.

Virulent bacterial strains have developed complex metabolic and regulatory pathways to enable them to thrive in the in vivo environment during infection. Understanding how the regulatory networks operate requires manipulation of many genes and expressing them temporally and spatially at different levels or under separate regulatory controls. In the case of gram-positive bacteria including staphylococci, the introduction of shuttle vector systems has greatly facilitated gene structure-function studies. However, the construction and range of application of the vectors available to date for gram-positive bacteria lack flexibility and variety. Staphylococcal shuttle vectors are mainly based on plasmid chimeras derived from the assemblage of restriction enzyme-generated DNA fragments containing the function of interest. This strategy has several major disadvantages. (i) The cloning of fragments for the backbone structures is limited by the availability of restriction sites in the 5′ and 3′ sequences flanking the region of interest. (ii) The choice of restriction sites available for the cloning of novel fragments is thus restrained. (iii) The fragments are often too big and not optimized. (iv) Interchangeability is limited.

To address these concerns, we have developed a novel series of powerful Escherichia coli-staphylococcal shuttle vectors. Our approach is based on PCR-designed cassettes, which can be easily exchanged, providing flexibility. The main elements of the system comprise (i) staphylococcal pT181-based low-copy-number, high-copy-number and thermosensitive replicons (1, 17), (ii) the low-copy-number theta replicon of plasmid pI258 (4, 20), (iii) staphylococcal selectable markers (choice of erythromycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, and spectinomycin resistance) (5, 6, 8, 15, 28), (iv) an Escherichia coli ColE1-based replicon and selectable marker (ampicillin resistance) (32), (v) a staphylococcal φ11 phage fragment that allows extremely high frequency transduction (14, 19), (vi) a fragment of the staphylococcal pathogenicity island SaPI1 that enables site-specific integration into the Staphylococcus aureus chromosome (13, 25), (vii) an expanded multiple cloning site (MCS) derived from pUC19 (32), (viii) inducible and constitutive promoters (2, 22), and (ix) reporter genes (3, 27, 29, 30).

In this paper, we present and describe the structure and properties of the first generation of this novel series of modular shuttle vectors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and cultures.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. NCTC8325 is a naturally occurring strain of S. aureus, which is lysogenic for three phages, φ11, φ12, and φ13 (16). The restriction-defective S. aureus strain RN4220 is a nonlysogenic derivative of NCTC8325 and is an efficient recipient for E. coli DNA (11). Routinely, staphylococcal inocula were prepared by overnight growth at 37°C (or at 32°C for plasmids with thermosensitive replication) on GL agar medium with antibiotics as appropriate (18). Broth cultures were grown in CY broth supplemented with glycerol phosphate (0.1 M) at 37°C with vigorous aeration (shaking at 250 rpm) (18). Cell growth was turbidimetrically monitored with a Klett-Summerson colorimeter with a green filter at 540 nm (Klett, Long Island City, N.Y.) or with a THERMOmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices) at 650 nm. E. coli DH5α and TOP10 were used as bacterial hosts for plasmid construction (26). All E. coli strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani medium either in liquid with shaking (250 rpm) or on agar plates at 37°C. Whenever required, suitable antibiotics were added to the media as follows: chloramphenicol at 10 μg/ml for S. aureus (plasmid selection), erythromycin at 10 μg/ml for S. aureus and 500 μg/ml for E. coli (plasmid selection), kanamycin at 250 μg/ml for S. aureus and 50 μg/ml for E. coli (plasmid selection), tetracycline at 5 μg/ml (chromosomal selection) and 10 μg/ml (plasmid selection) for S. aureus, and spectinomycin at 1,000 μg/ml for S. aureus and 100 μg/ml for E. coli (plasmid selection).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Host for DNA cloning | Lab strain collection |

| TOP10 | Host for DNA cloning | Invitrogen Life Technologies |

| S. aureus | ||

| NCTC8325 | Propagating strain for typing phage 47 | Lab strain collection |

| RN11 | Harbors pI258; lysogenic for φ11, φ12, and φ13 | Lab strain collection |

| RN27 | RN450 lysogenic for 80α, φ13 | 16 |

| RN450 | NCTC8325 cured of φ11, φ12, and φ13 | 16 |

| RN1329 | 8325-4; lysogenic for φ11; Spr [Tn554(aad9)] | Lab strain collection |

| RN2424 | 8325 (pT181) | Lab strain collection |

| RN2442 | 8325-4 (pE194) | Lab strain collection |

| RN4220 | Restriction-defective derivative of RN450 | 11 |

| RN4253 | 8325 (pRN8061) | Lab strain collection |

| RN4416 | RN27 (pSA0331) | Lab strain collection |

| RN5830 | 8325-4 (pC194) | Lab strain collection |

| RN6851 | RN6502 (pRN6680) | Lab strain collection |

| RN6734 | agr+; 8325-4 derivative | Lab strain collection |

| RN7206 | RN6734Δagr::tet(M) | Lab strain collection |

| RN7885 | JM109 (pRL189) | Lab strain collection |

| RN8972 | RN4220 (pRN6998) | 25 |

| RN9011 | RN4220 (pRN7023) | 25 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | Apr; ColE1 compatibility group origin of replication 867; 2686 bp | 32 |

| pT181 | pT181wt; Tcr; Inc3; naturally occurring; ±22 copies/cell; 4,440 bp | 1, 17 |

| pRN8061 | pT181cop-623; Tcr; Inc3; ±400 copies/cell; 4,440 bp | 1, 17 |

| pSA0331 | pT181cop-634repC4; Tsr; Tcr; Inc3; ±145 copies/cell; 4,440 bp | 1, 17 |

| pI258 | Naturally occurring β-lactamase plasmid; 28 kb | 21 |

| pE194 | Emr (ermC); Inc11; naturally occurring; 3725 bp | 5 |

| pAT21 | Apr Kmr; pBR322Ω1.5-kb pJH1 ClaI (aphA-3) | 28 |

| pC194 | Cmr (cat194); Inc8; naturally occurring; 2,910 bp | 6 |

| pRN6680 | Apr Tcr; pBluescriptΩ2.9-kb pMVN6 Smal-HindII [tetA(M)] | 15 |

| pRN6998 | pE194tsΩpUC18-MCSΩSaPI1sek-int-attS; 8,319 bp | 25 |

| pRN7023 | pC194tsΩpUC19-MCSΩSaPI1int | 25 |

| pRL189 | luxAB | Gift of Peter Wolk |

| pBD4 | LITMUS28Ωgfpmut2-ermC; 4,784 bp | Gift of D. J. Bartels and E. P. Greenberg |

General DNA procedures.

Routine general molecular biology assays were performed according to standard procedures (26). Chromosomal DNA from S. aureus was prepared as described elsewhere (13). Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) kits were used with minor modifications for the isolation of plasmid DNA, extraction of DNA fragments from agarose gels, and purification of PCR products and digested fragments.

Primers and PCRs.

The oligonucleotides used as primers are listed in Table 2. The polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis-purified primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa) were designed to add restriction sites (underlined bases) upstream and downstream of the amplified products. All PCRs were performed using Pwo polymerase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.). Cycling times and temperatures were according to the properties of the primer pairs. Ordinarily, reactions were carried out for 25 cycles with an annealing temperature of 55°C.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used for plasmid construction

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | F or Rb | DNA template | Cassette |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 672 | GAA TAT GCA TGC GAT AAT GGC GCCTTT GCG GAA AGA GTT AGT AAG TTA ACA G | F | pT181, pRN8061, pSA0331 | pT181 replicon |

| 671 | TGA ACG GGC CCAATA AAA GCA ATC AAT GAA CCA AG | R | pT181, pRN8061, pSA0331 | pT181 replicon |

| P386 | TAC TTG GGG CCCTCG ATG ATT ACC AGA AGT TCT C | R | pI258 | pI258 replicon |

| P387 | TAG CAT GGC GCCGTT TTA TCT TCA TCA CTT GTA TTA ATC | F | pI258 | pI258 replicon |

| 673 | GAT CAT CTC GAG CGG CCG CAT AGT TAA GCC AGC CCC GAC | F | pUC19 | amp ColE1 ori |

| 623 | GAT TAG CAT GCA GCG GCC GCC AGC TCA CTC AAA GGC GG | R | pUC19 | amp ColE1 ori |

| 675 | CTC TGC GGG CCC ACC TAG GAA TTG AAT GAG ACA TGC TAC | F | pE194 | ermC |

| 674 | TCT CTT CTC GAG CGC CGC GGA AAA CTG GTT TAA GCC GAC | R | pE194 | ermC |

| 599 | GTT TAA GGG CCC ACC TAG GCA AAT ATG CTC TTA CGT GC | F | pRN6680 | tet(M) |

| 600 | CTA TGA CTC GAG GCC GCG GAA ATA TTG AAG GCT AGT CAG | R | pR6680 | tet(M) |

| 617 | GTT TAA GGG CCC ACC TAG GTA TTA TCA AGA TAA GAA AG | F | pC194 | cat194 |

| 618 | CTA TGA CTC GAG GCC GCG GCC TTC TTC AAC TAA CGG GG | R | pC194 | cat194 |

| 619 | GTT TAA GGG CCC ACC TAG GGG TTT CAA AAT CGG CTC CG | F | pAT21 | aphA-3 |

| 620 | CTA TGA CTC GAG GCC GCG GCG CTC GGG ACC CCT ATC TAG C | R | pAT21 | aphA-3 |

| 676 | GTT TAA GGG CCC ACC TAG GAT CGA ATC CCT TCG TGA GCG | F | Tn554 | aad9 |

| 677 | TCT CTT CTC GAG GCC GCG GTA ATA AAC TAT CGA AGG AAC | R | Tn554 | aad9 |

| 583 | TAC GTT GCA TGCAGC TTA CTA TGC CAT TAT T | F | pI258 | PblaZ |

| 584 | ATT CGT CTG CAGAAT AAA CCC TCC GAT ATT AC | R | pI258 | PblaZ |

| 594 | TGC GAT GCA TGCGCA CTT ATT CAA GTG TAT TT | F | pI258 | Pcad-cadC |

| 595 | AAT AAT GTC GAC CTG CAGGTT CAG ACA TTG ACC TTC AC | R | pI258 | Pcad-cadC |

| 616 | TCG ATA GAA TTC GTT AAC TAA TTA ATA TCG GAG GGT TTA TTT TG | F | pI258 | blaZ |

| 628 | AAC AGT GGC GCCTGT CAC TTT GCT TGA TAT ATG AG | R | pI258 | blaZ |

| 589 | TCG ATA GAA TTC GTT AAC TAA TTA ATT TAA GAA GGA GAT ATA CAT ATG AG | F | pDB4 | gfpmut2 |

| 662 | AGC ATA GGC GCG CCT TAT TTG TAT AGT TCA TCC ATG CCA | R | pDB4 | gfpmut2 |

| 601 | AAG ATT GAA TTC GTT AAC TAA TTA ATC ACC AAA AAG GAA TAG AGT ATG AAG | F | pRL189 | luxAB |

| 612 | AAG TAT GGC GCG CCA AAA AGG CAA TCT AAT ATA GAA ATT GCC | R | pRL189 | luxAB |

| 658 | TTA TCT GAA TTC AGG CGC GCCTAT TCT AAA TGC ATA ATA AAT ACT G | F | pI258 | TT |

| 628 | AAC AGT GGC GCCTGT CAC TTT GCT TGA TAT ATG AG | R | pI258 | TT |

| 655 | TTA ATC CGC GGT GTC ATT ATT TC | F | φ11 | φ11 EcoRI-K |

| 656 | ATC TTC TCG AGT AAA AGG CTT CGG AAG TAG | R | φ11 | φ11 EcoRI-K |

| P805 | TTG ATG GGC CCG AAA GAT GTT GGT ATT GAT AAA GAA G | F | pRN6991 | SapI1-attS |

| P806 | TGG AAC CTA GGA GCT GGA AAT ATT CGT TAT TTA TG | R | pRN6991 | SapI1-attS |

Restriction sites are underlined. Bases complementary to the template are italicized. Bases in boldface represent stop codons.

F, forward; R, reverse.

Plasmid construction.

All plasmid constructs were created using E. coli DH5α or TOP10 as the intermediate host. Inserts corresponding to the various PCR-generated products were digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, Mass.). The digested products were agarose gel purified and ligated to the correspondingly digested vectors. Ligation was carried out for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 16°C with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs Inc.). Transformation in E. coli was carried out as described previously (26). Newly generated plasmids were purified, and plasmid restriction digestion patterns were examined. In addition, the inserted DNA modules or junction fragments were sequenced on both strands to ensure that no misincorporation of nucleotides occurred during the PCR. One microgram of each plasmid previously amplified and purified in E. coli was used to transform S. aureus RN4220 by protoplast transformation or electroporation as described elsewhere (18). Plasmid from S. aureus was then purified and checked by restriction digestion pattern analysis. Whole-cell lysate analysis was additionally performed to test for possible DNA recombination or plasmid instability.

Plasmid DNA analysis.

Plasmid DNA from S. aureus strains was analyzed in sheared whole-cell minilysates of exponentially growing cultures by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Copy numbers were determined as the calculated ratios of plasmid to chromosomal DNA by direct fluorescence densitometry of the ethidium bromide-stained gel patterns (24). Plasmid segregational stability was scored by growing plasmid-containing strains in nonselective liquid cultures for approximately 100 generations. After serial dilutions, the cells were plated on nonselective agar. One hundred to 200 colonies were transferred onto nonselective and selective agar plates to determine the proportion of bacteria that still contained the plasmid.

Plasmid thermosensitivity.

In thermosensitivity studies, 32 and 43°C were the permissive and nonpermissive temperatures, respectively. Plasmid thermosensitivity was examined for three independent staphylococcal clones for each plasmid to be analyzed. After overnight growth at 32°C on agar plates containing the selective antibiotic, strains were streaked for single colonies on nonselective media and incubated at 43°C for 24 h. One hundred to 200 colonies were picked on agar containing either no selection or the selective antibiotic and incubated at 32°C for 24 h. All picked colonies that showed growth only on the nonselective media had lost the plasmid after growth at 43°C. Loss of the plasmid was then verified by whole-cell minilysate analysis.

Phage transduction.

The preparation and analysis of phage lysates were performed essentially as described previously with minor modifications (18). For the preparation of phage lysates, early-exponential-phase cells were transferred to CY broth-phage buffer (1:1) and infected with the phage at a multiplicity of 0.1 to 1. Lysis took place during slow shaking at 32°C. Lysates were then centrifuged and sterilized by passage through a 0.45-μm-pore-size Millipore filter. Transduction samples consisted of mixtures of early-exponential-phase cells with phage in phage buffer containing 4 mM CaCl2. For transduction of phage-sensitive recipients, 17 mM sodium citrate was added to the agar.

Reporter protein measurements.

For induction of the Pcad-cadCΩblaZ fusion, CdCl2 was added at various concentrations to early-exponential-phase staphylococcal cultures and the cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking for 90 min. Samples were equalized to constant cell mass and assayed for β-lactamase activity by the nitrocefin spectrophotometric method (23) modified as described previously (9). β-Lactamase activity is expressed as initial reaction rate in milliunits of optical density at 490 nm (OD490) per minute. All assays were performed at least in triplicate. Luciferase was evaluated qualitatively for cultures grown on agar by using a Hamamatsu imaging camera (kindly provided by Xenogen, Inc.), following the addition of the luciferase substrate decanal. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) was detected visually in cultures grown on agar, by use of a long-wave UV source. Alternatively, GFP activity in single cells was evaluated with a fluorescence microscope. For quantification of green fluorescence, cultures were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth medium with shaking at 37°C, and the growth curve was monitored by measuring the OD620. Samples were withdrawn every hour, centrifuged, and suspended into the same volume of phosphate-buffered saline buffer. The green fluorescence was then measured with a spectrofluorometer (Perkin-Elmer Wallac Victor2 plate reader) by excitation at a wavelength of 485 nm and detection of emission at 515 nm. Values correspond to relative fluorescence versus OD620.

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA was prepared from samples equalized to the same number of cells. The amount of RNA in each sample was normalized to that of the rRNA, which was quantitated by scanning an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel with an Alpha Innotech video imager. Northern blot analysis was carried out as described previously (10) using as probe a [32P]dATP-labeled blaZ-internal DNA fragment. A probe consisting of a [32P]dATP-labeled PCR product specific for 16S rRNA served as a loading control.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for sequences used to design the cassettes are as follows: J01764 (pT181 replicons), AF203377 (pI258 replicon), L09137 (amp ColE1 ori), X02588 (aad9), V01547 (aphA-3), NC002013 (cat194), J01755 (ermC), M21136 [tetA(M)], AF424781 (φ11 EcoRI-K), U93688 (SaPI1-attS), M62650 (PblaZ, blaZ, TT), J04551 (Pcad-cadC), U73901 (gfpmut2), and X06758 (luxAB).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cassette strategy for vector construction.

The ability to switch and/or add functional modules readily facilitates the construction of novel vectors. For this purpose, we designed a novel cassette strategy for the construction of a new family of staphylococcal-E. coli shuttle vectors. All cassettes were constructed by PCR amplification with primers containing flanking restriction sites. The amplified products were purified and digested with the restriction enzymes recognizing the flanking sites and then used for cloning. Each of the vectors was assembled using the flanking restriction sites shown in Fig. 1 (for an example, see pRN7145 in Fig. 2). In cases where two sites are shown, the outer one was used. Note that the replicon cassettes were cloned using their ApaI and SphI sites and that the MCS was subsequently inserted between the SphI and NarI sites at the left end of the cassette. Any cassette can be removed and replaced using these same restriction enzymes, and the constructs can be readily verified by gel electrophoresis of restriction digests. New cassettes can be inserted and existing ones can be interchanged, thus providing a versatile method to build new vectors.

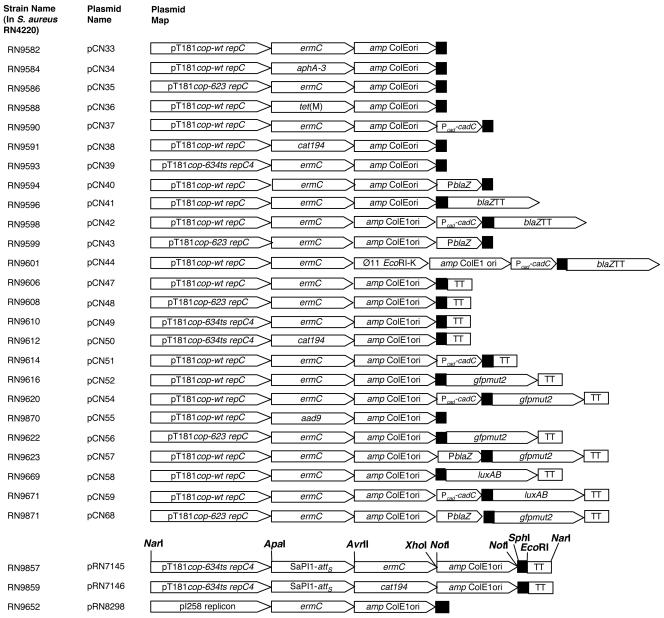

FIG. 1.

Cassette restriction maps of shuttle vector pCN series. The gene designations include pT181 cop-wt repC, pT181 cop-623 repC, pT181 cop-634 repC4, and pI258 replicon for replication in Staphylococcus. Each pT181 cassette contains the single-stranded origin of replication, double-stranded origin of replication, the copy control system, and the repC gene encoding the replication protein RepC of the pT181 rolling-circle replicon. The pI258 replicon includes the plasmid's replication origin, rep protein gene, and, presumably, the copy control system, though this has not been defined to date. Antibiotic resistance modules consist of aad9 (aminoglycoside adenyltransferase-encoding gene of Tn554 for spectinomycin resistance), aphA-3 (for aminoglycoside 3′-phosphotransferase, the kanamycin resistance gene of pAT21), cat194 (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase-encoding gene of pC194 for chloramphenicol resistance), ermC (ribosomal methylase-encoding gene of pE194 for erythromycin resistance), and tet(M) (gene of pRN6680 for tetracycline resistance). Additional modules include φ11 EcoRI-K (enabling high-frequency transduction), SaPI1-attS (enabling site-specific integration into the SaPI1 chromosomal attachment site in the presence of SaPI1 integrase in trans), amp ColE1 ori (bla gene conferring ampicillin resistance and ColE1ori for replication in E. coli), blaZ (gene from pI258 encoding the β-lactamase reporter), gfpmut2 (fluorescence-activated cell sorting-optimized mutant version gfpmut2 of the green fluorescent gene of A. victoria encoding the GFP reporter), luxAB (gene encoding the luciferase determinant from V. fischeri), TT (blaZ transcriptional terminator), PblaZ (constitutive β-lactamase promoter module), and Pcad-cadC (cadmium-inducible promoter module). For transcriptional fusions, a three-way translational stop codon was inserted upstream of each promoterless reporter gene. The transcriptional terminator of blaZ was inserted downstream of each reporter gene to prevent any read-through of the repC gene from the promoter to be tested. The MCS from pUC19 is symbolized by a black box. Each cassette is flanked by restriction sites introduced into the PCR product used for its cloning, as indicated. Adventitious sites corresponding to those of the pUC19 MCS are indicated. Those occurring in any of the three backbone cassettes are crossed out in the representation of the MCS.

FIG. 2.

Series of pCN shuttle vectors. The first generation of pCN shuttle vectors is here represented in linear form, opened at the NarI site between the replicon and MCS cassettes. Each of these was assembled using the flanking restriction sites shown in Fig. 1. In cases where two sites are shown, the outer one was used. Note that the replicon cassettes were cloned using their ApaI and SphI sites and that the MCS was subsequently inserted between the SphI and NarI sites at the left end of the cassette. Any cassette can be removed and replaced using these same restriction enzymes. For details of each module, please refer to Fig. 1.

Construction of the basic shuttle vector backbone.

The backbone contains the basic functional elements of the shuttle vectors. (i) For replication in S. aureus, we used two plasmid replicons. First, we employed the well-characterized rolling-circle replicon of plasmid pT181 (1, 17), including the initiator protein gene, repC; the copy control region; and the leading- and lagging-strand origins. We included the wild-type replicon (cop-wt repC) and two derivatives—a high-copy-number mutant (cop-623 repC) and a thermosensitive replication mutant (cop-634ts repC4). Second, we employed the low-copy-number theta replicon of plasmid pI258, a well-characterized S. aureus penicillinase plasmid (4, 20). (ii) For selection in S. aureus, we chose the pE194 ermC macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance gene (5, 8). (iii) For replication and selection in E. coli, we used a pUC19 fragment that contains the ColE1 replicon origin and the ampicillin resistance gene bla, also known as amp (32). This module can easily be removed by digestion with NotI and religation. (iv) As an MCS, we inserted the SphI-NarI fragment of pUC19 (32). (v) The basic modules were connected by ApaI, AvrII, NarI, NotI, SacII, and XhoI, restriction sites that are unique or very rare in the vector system cassettes (Fig. 1). The backbone vector was constructed starting with the pT181 cassette. This was amplified by using as a template the pT181 wild-type plasmid from strain RN2424 and by using as primers oligonucleotides 672 and 671. The PCR product was then purified and digested with SphI and ApaI. Next, the ermC cassette was amplified by using as a template plasmid pE194 from strain RN2442 and as primers oligonucleotides 675 and 674. After purification, the PCR product was digested with ApaI and XhoI. For the amplification of the amp ColE1 ori cassette, plasmid pUC19 was used as a template and oligonucleotides 673 and 623 were used as primers. The purified product was digested with XhoI and SphI. The three digested DNA cassettes were then assembled by a three-fragment ligation. Finally, the MCS fragment of pUC19 was introduced at the SphI and NarI sites, thus generating plasmid pCN33 (Fig. 1 and 2). This plasmid was then used to create the first generation of a family of derivatives that offer variants of the staphylococcal replication and selection functions as well as novel additional cassettes for transduction and integration functions and for gene expression analysis. The various members of this set of vectors are depicted in linear form in Fig. 2.

Low-copy-number, high-copy-number, and thermosensitive rolling-circle pT181-based replicons for gram-positive bacteria.

In earlier studies numerous pT181 derivatives with mutations affecting replication and its control were isolated (1, 7, 17). We used two of these mutants to construct two additional versions of the pT181cassette (Fig. 1). The three different pT181 staphylococcal replicon cassettes offer then (i) a low-copy-number (∼20 to 25 copies/cell) version (pT181copwt repC) for, e.g., studying the fine regulation of promoter activities in vivo; (ii) a high-copy-number (300 to 400 copies/cell) version (pT181cop-623 repC) for, e.g., overexpression purposes; and (iii) a thermosensitive high-copy-number version (pT181cop-634ts repC4) for, e.g., helper functions and gene replacement. The pT181cop-623 repC and pT181cop-634ts repC4 cassettes were obtained by amplification of pRN8061 and pSA0331 with primers 672 and 671. Each cassette was digested by NarI and ApaI and used to replace the pT181copwt repC cassette of pCN33, thus creating pCN35 and pCN39, respectively. After introduction of pCN33, pCN35, and pCN39 into S. aureus RN4220, the functionality of each replication module was analyzed. The three vectors were stably maintained in S. aureus RN4220 when cultured at 37°C for pCN33 and pCN35 and at 32°C for the thermosensitive vector pCN39. After approximately 100 generations without selective pressure, 99% of 200 analyzed clones were still erythromycin resistant and exhibited the same copy number as before passage. The plasmid copy number of each of these three vectors corresponded to that of the original plasmid from which the replicons originated (1, 17) (Fig. 3A). The thermosensitivity of the pT181cop-634 repC4 replicon of pCN39 was assessed by testing for loss of the plasmid at 43°C. After overnight growth at 43°C, none of 200 colonies tested were erythromycin resistant, indicating that pCN39 had retained the replication thermosensitivity of its pT181 parent. As shown in Fig. 3B, loss of pCN39 was further confirmed by whole-cell minilysate analysis.

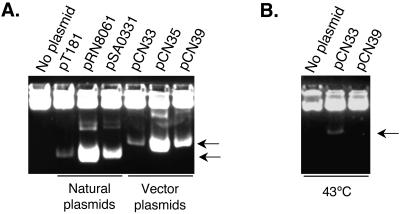

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the pT181-based staphylococcal modules. Whole-cell sheared minilysates of S. aureus RN4220 strains containing the indicated plasmids were separated on 1% agarose in Tris-borate buffer for 18 h at 2.5 V/cm, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed. Samples corresponding to equivalent numbers of cells were used to permit comparison. (A) Strains were grown at 32°C. Lane 1, RN4220; lane 2, RN2424; lane 3, RN4253; lane 4, RN4416; lane 5, RN9582, lane 6, RN9586; lane 7, RN9593. (B) Experiments were conducted at 43°C. Lane 1, RN4220; lane 2, RN9582; lane 3, RN9593. The heavy upper band corresponds to sheared chromosomal DNA. The supercoiled plasmid bands are indicated with arrows. Intermediate plasmid bands correspond to topoisomers and multimers.

Low-copy-number theta replicon.

Earlier studies have identified a family of relatively large staphylococcal plasmids (25 to 35 kb), responsible for resistance to penicillin and several inorganic ions and referred to as “penicillinase plasmids” (20). These have low copy numbers (∼5 copies/cell) and use the theta mode of replication (E. Murphy and R. P. Novick, unpublished data) (4). One of these, pI9789, has been sequenced in its entirety (4), and its replicon is very closely related, possibly identical, to that of pI258, a penicillinase plasmid prototype of incompatibility group I (20). We therefore amplified a 2.5-kb segment using primers 386 and 387, derived from the pI9789 replicon region sequence, with pI258 DNA as the template, and cloned it into pCN33 in place of the pT181copwt repC cassette, giving rise to pRN8298 (Fig. 1 and 2). This plasmid was transferred to RN4220, and its low copy number was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis of whole-cell minilysates.

Panel of antibiotic resistance markers for selection.

Selective markers for staphylococcal genetics are almost entirely derived from clinical antibiotic resistance determinants. In addition to the standard ermC gene, we have constructed cassettes from four additional resistance genes, aad9, aphA-3, cat194, and tetA(M), conferring resistance to spectinomycin, kanamycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline, respectively (Fig. 1). Each of these was designed to include the native promoter and transcriptional terminator sites as well as the coding sequence of the resistance gene. These cassettes were created by PCR by using primers and templates listed in Table 2. The purified PCR products, digested by ApaI and XhoI, were used to replace the ermC module in pCN33, thus generating pCN55, pCN34, pCN38, and pCN36, respectively. Plasmids were introduced into S. aureus RN4220 by electroporation with the appropriate selection. It is worthwhile noting that E. coli strains DH5α(pCN55), DH5α(pCN34), and DH5α(pCN33) were selectable with spectinomycin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and erythromycin (250 μg/ml), respectively. However, for unknown reasons, we were unable to use selection with chloramphenicol and tetracycline for E. coli strains DH5α(pCN38) and DH5α(pCN36), respectively, and therefore, resistance to ampicillin was generally utilized.

High-frequency transduction module.

Electroporation and protoplast transformation are normally used to introduce DNA into staphylococci. Although they can also be used for transfer between staphylococcal strains, phage-mediated transduction is more commonly used, is much more convenient, and is readily applicable to certain well-characterized laboratory strains. With many clinical or environmental isolates, standard transduction frequencies are often far too low for successful genetic transfer, probably because of restriction incompatibilities. We have circumvented this limitation on the basis of earlier reports showing that insertion of any restriction fragment of phage φ11 into a small rolling-circle plasmid such as pT181 or pCW58 caused a dramatic increase in transduction efficiency with this or related phages (14, 19). Transduction frequencies between 0.1 and 1.0 per plaque-forming particle were observed depending on the size (0.3 to 2 kb), but not the genetic content, of the phage fragment. More recently, we have failed to find a single strain of S. aureus that could not be transduced by a pT181 derivative, pRN8151, containing φ11 EcoRI-K (unpublished data). We exploited this feature to design a high-frequency transduction module. The ∼1-kb EcoRI-K fragment of phage φ11 was amplified using φ11 DNA from strain RN0011 as template and primers 655 and 656. The PCR product was purified, digested with SacII and XhoI, and cloned into pCN42, thus generating pCN44. Phage φ11 and 80α transducing lysates were prepared with strains of S. aureus RN9598 [RN4220(pCN42)] and RN9601 [RN4220(pCN44)]. Transduction of pCN42 and pCN44 with φ11 and 80α was performed using S. aureus RN450 as recipient. Transduction frequencies of about 7 × 10−3 transductants per PFU were achieved with pCN44 compared to 8 × 10−7 transductants per PFU with pCN42. The pCN44 transduction frequency was somewhat lower than that of pRN8151, possibly owing to the much larger size of the vector, but is sufficient for widespread transductional transfer among native S. aureus isolates. Whether these frequencies will be further lowered by additional cloned DNA remains to be seen.

Site-specific integration module.

The ability to obtain single-copy integrated derivatives of cloned segments is often critical with respect to stability and to effects of gene dosage. Ideally, one would prefer to reintegrate a cloned segment at its native chromosomal location; the use of a constant site, however, may have certain advantages, as well as being much more practical. Although a very effective site-specific integration system, using attφ54, is available (12), the φ54 attachment site is within the geh (lipase) coding sequence. This may complicate certain studies of gene regulation, since geh is subject to a variety of regulatory stimuli. We therefore chose a different site-specific integration system, that of the phage-related pathogenicity island SaPI1 (13, 25), on the basis of preliminary studies suggesting that there is very little, if any, transcription through this site (unpublished data). Accordingly, we amplified a 906-bp segment from plasmid pRN6998 containing attS, the SaPI1 attachment site (25), by using primers 805 and 806, and cloned this product into pCN49 and into pCN50, generating pRN7145, and pRN7146, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1 and 2. pRN7145 was tested for site-specific integration in an RN4220 derivative containing a second plasmid, pRN7023, expressing SaPI1 integrase (25). In the absence of pRN7023, all of 100 colonies tested after overnight growth at 43°C on nonselective medium were erythromycin sensitive and had lost the plasmid, whereas all of 100 colonies of the two-plasmid strain remained erythromycin resistant but had also lost the autonomous attS plasmid, consistent with integration. Integration was confirmed for four colonies by a PCR primed with oligonucleotides that span the SaPI1-chromosomal left junction (25).

Reporter genes.

As reporter genes for promoter-gene fusions, we selected blaZ, luxAB, and gfp. The blaZ gene encodes plasmid pI258 β-lactamase, a secreted protein, which has previously been developed as a reporter for transcriptional and translational fusions in staphylococci (29, 30). Vibrio fischeri luxAB is an extremely sensitive indicator of promoter function, its only disadvantage being that its measurement requires a luminometer or a luciferase-sensitive imaging system. GFP, the product of Aequorea victoria gfp, has been used very widely as a reporter, and many variants are available (3). We used a mutant (gfpmut2) that is activated by long-wave UV light as well as by blue light at 485 nm. For this first generation of shuttle vectors, we developed transcriptional reporter gene fusions. Each reporter module was designed such that it contains a functional ribosomal binding site (RBS) and translational start codon following a series of stop codons in all reading frames. The reporter gene is silent unless a promoter is inserted in the correct orientation at a restriction site immediately upstream of the reporter module. To ensure that transcription of the reporter gene would not interfere with the expression of downstream genes (notably the staphylococcal replicon cassette) and vice versa, a module containing an efficient bidirectional transcriptional terminator was created and inserted directly upstream of the staphylococcal replicon cassette. A DNA fragment containing the transcriptional terminator of the blaZ gene was amplified using plasmid pI528 as template and primers 658 and 628. The forward oligonucleotide 658 included an AscI site, just downstream of the EcoRI site, thus providing an additional restriction site in the MCS for the cloning of additional reporter genes that do not contain their own transcriptional terminator. The digested amplified product was then cloned into the EcoRI and NarI sites of pCN33, pCN35, and pCN39, thus creating pCN47, pCN48, and pCN49, respectively.

The blaZ reporter module, containing the blaZ RBS and transcriptional terminator as well as the structural gene, was amplified from plasmid pI258 by using oligonucleotides 616 and 628. The PCR product was then cloned to the promoterless version of the system vector pCN33, at the EcoRI and NarI sites, thus generating pCN41. A DNA segment containing the gfpmut2 coding sequence from its translational start codon to its stop codon was amplified from pDB4 (kindly provided by Doug Bartels and Pete Greenberg) by using primers 589 and 662. The forward primer 589 contained stop codons in all three reading frames followed by a functional staphylococcal RBS sequence. The gfpmut2 product was digested with EcoRI and AscI, purified, and cloned into the promoterless shuttle vector containing the transcriptional terminator, pCN47, thus generating pCN52. The luxAB segment was amplified from plasmid pRL189 (kindly provided by Peter Wolk), with primers 601 and 612, digested with EcoRI and AscI, purified, and cloned into the promoterless shuttle vector pCN33, generating pCN58. The promoterless versions of the reporter gene clones were used as controls in reporter gene assays further described below.

Constitutive and inducible promoters for transcriptional gene fusions.

A widely used method of evaluating the function of a gene is to induce its expression ectopically and monitor the effects. This method has potential flaws owing to differences in sequence context and gene dosage; nevertheless, it is very useful if used carefully and always has the potential of reinsertion into the chromosome. Accordingly, we have incorporated two different inducible promoters, PblaZ (22) and Pcad-cadC (2), derived from pI258, into the system. Inducibility of the former depends on the presence of a copy of the regulatory genes blaI and blaR1 in trans. In the absence of these, it is a highly active constitutive promoter and is somewhat unstable. PblaZ was amplified from pI258 as a 145-bp PCR product with flanking PstI and EcoRI/SalI sites; digested with PstI and EcoRI; and cloned into pCN33, pCN35, pCN52, and pCN56, generating pCN40, pCN43, pCN57, and pCN68, respectively. For a test of constitutive PblaZ function, we cloned the promoter into pCN52 and pCN56, which contain a promoterless gfpmut2, generating pCN57 and pCN68, respectively. Early-exponential, mid-exponential, late-exponential, and late-stationary-growth-phase cultures of S. aureus RN9623 (RN4220 harboring pCN57) and RN9871 (RN4220 harboring pCN68) were visualized by phase-contrast and epifluorescence microscopy. All bacterial cells that were observed by phase-contrast microscopy were fluorescent, suggesting that the promoter PblaZ is functional and that gfpmut2 was constitutively expressed under its control (data not shown). No fluorescence was detected in RN4220 strains harboring the vector containing either the reporterless PblaZ promoter (pCN40 or pCN43) or the promoterless gfpmut2 gene (pCN52 or pCN56). Similarly, GFP fluorescence of strains containing gfpmut2 under PblaZ control was readily detectable macroscopically in cultures grown on agar, by using a long-wave UV lamp (data not shown). Further quantification of fluorescence following the growth curve confirmed the constitutive expression of gfpmut2 under the control of the PblaZ promoter in RN4220 harboring pCN57. The control strains, RN4220 containing either the reporterless PblaZ promoter (pCN40) or the promoterless gfpmut2 gene (pCN52), showed values comparable to those of RN4220 (autofluorescence) (Fig. 4).

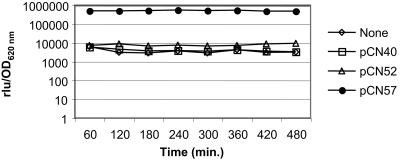

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the constitutive promoter cassette PblaZ. Data are for RN4220 derivatives containing the indicated plasmid. Expression of the gfpmut2 reporter gene was monitored during growth at 37°C. The vertical axis represents relative fluorescence versus OD620 of the culture.

Inducibility of the Pcad-cadC module is inherent in the promoter cassette, which contains the repressor gene, cadC, and is inducible by CdCl2 in micromolar concentrations (2). The Pcad-cadC module was PCR amplified from pI258 as a 592-bp segment with flanking PstI and EcoRI sites, by using oligonucleotides 594 and 595 as primers. It was digested with these enzymes and cloned into pCN33, pCN41, and pCN47, generating pCN37, pCN42, and pCN51, respectively. The functionality of the Pcad-cadC module was tested by growing RN4220 strains containing pCN41, pCN42, and pCN51 in the presence or absence of inducing concentrations of CdCl2 and measuring the activity of the attached blaZ reporter. As shown in Fig. 5A, there was a low basal level of β-lactamase activity with pCN51 (reporterless Pcad-cadC promoter). In a strain containing pCN42 (Pcad-cadCΩblaZ fusion), dose-dependent β-lactamase activity induction with CdCl2 from 1 to 15 μM was observed. Higher levels of CdCl2 were growth inhibitory. Maximal induction was seen for 5 to 15 μM CdCl2, giving an induction ratio of about 35. A trace of β-lactamase activity was seen with the promoterless blaZ reporter pCN41. This trace of activity could represent a very minor read-through from an upstream promoter or the very weak activity of an adventitious promoter-like sequence. Induction of β-lactamase gene transcription by CdCl2 was further analyzed by Northern blot analysis. In keeping with the β-lactamase measurements, the blaZ transcript was detected in RN4220 containing pCN42 only upon CdCl2 induction (Fig. 5B). No blaZ transcript was observed in the control strains. We also tested the Pcad-cadC module for gfp induction by cloning gfpmut2 into pCN52 between the SphI and PstI sites, generating pCN54. In RN9620 [RN4220(pCN54)] gfp induction by CdCl2 was readily detected by UV-induced fluorescence on an agar surface or by fluorescence microscopy (data not shown). No fluorescence was observed without induction or with the control strains RN4220, RN9614 [RN4220(pCN51)], and RN9616 [RN4220(pCN52)]. The Pcad-cadC promoter module was also cloned into the promoterless luxAB reporter vector, pCN51, thus generating pCN59. The latter but not the former showed CdCl2-inducible luciferase production on an agar surface, which was detected by the Hamamatsu charge-coupled device imaging camera after the addition of a drop of decanal to the petri dish cover. The Pcad-cadC system represents a valuable addition to the other inducible promoters available for staphylococci, which have certain disadvantages such as a direct influence of the inducers on the expression of virulence or lack of utility of inducers in vivo. For instance, the xylose-inducible promoter Pxyl-xylR is repressible by glucose. The IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible Pspac-lacI was shown to interfere with the expression of virulence factors and the pathogenicity of S. aureus (31).

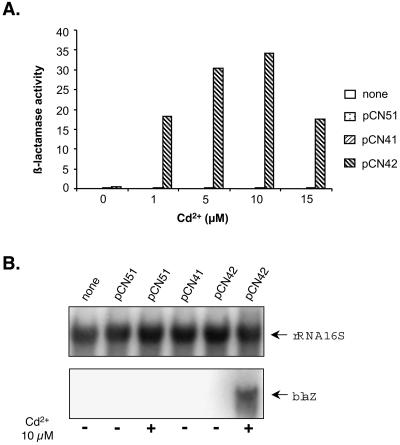

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the cadmium-inducible promoter cassette Pcad-cadC. Data are for RN4220 derivatives containing the indicated plasmid. Expression of the blaZ reporter gene was monitored during growth at 37°C. Low-density cultures were incubated at 37°C for 90 min in the absence or presence of different concentrations of Cd2+. Samples equalized to the same number of cells were analyzed. (A) The vertical axis represents β-lactamase activity (initial reaction rate in milliunits of OD490/min). (B) Total RNA was prepared and analyzed by Northern blot hybridization with a blaZ-specific probe. For loading controls, an rRNA 16S-specific probe was used.

The vector system combined with the GFP technology can thus offer great potential for real-time analysis of gene expression. Future generations of the system will include blue-white selection, an expanded MCS, conjugative transfer, gene knockout capability, and other replicons for both gram-positive and gram-negative hosts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01-AI30138 to R.P.N.

We are grateful to Hope F. Ross for stimulating and helpful discussions. We acknowledge Patrice Courvalin for his gift of plasmid pAT21, Peter Wolk for his gift of plasmid pRL189, and Doug Bartels and Pete Greenberg for their gift of plasmid pDB4.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carleton, S., S. J. Projan, S. K. Highlander, S. Moghazeh, and R. P. Novick. 1984. Control of pT181 replication. II. Mutational analysis. EMBO J. 3:2407-2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbisier, P., G. Ji, G. Nuyts, M. Mergeay, and S. Silver. 1993. luxAB gene fusions with the arsenic and cadmium resistance operons of Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 110:231-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cormack, B. P., R. H. Valdivia, and S. Falkow. 1996. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene 173:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Firth, N., S. Apisiridej, T. Berg, B. A. O'Rourke, S. Curnock, K. G. Dyke, and R. A. Skurray. 2000. Replication of staphylococcal multiresistance plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 182:2170-2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horinouchi, S., and B. Weisblum. 1982. Nucleotide sequence and functional map of pE194, a plasmid that specifies inducible resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin type B antibodies. J. Bacteriol. 150:804-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horinouchi, S., and B. Weisblum. 1982. Nucleotide sequence and functional map of pC194, a plasmid that specifies inducible chloramphenicol resistance. J. Bacteriol. 150:815-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iordanescu, S. 1976. Temperature-sensitive mutant of a tetracycline resistant staphylococcal plasmid. Arch. Roum. Pathol. Exp. Microbiol. 35:257-264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iordanescu, S. 1976. Three distinct plasmids originating in the same Staphylococcus aureus strain. Arch. Roum. Pathol. Exp. Microbiol. 35:111-118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji, G., R. C. Beavis, and R. P. Novick. 1995. Cell density control of staphylococcal virulence mediated by an octapeptide pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:12055-12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kornblum, J., S. J. Projan, S. L. Moghazeh, and R. P. Novick. 1988. A rapid method to quantitate non-labeled RNA species in bacterial cells. Gene 63:75-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Lofdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, C. Y., S. L. Buranen, and Z.-H. Ye. 1991. Construction of single-copy integration vectors for Staphylococcus aureus. Gene 103:101-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindsay, J. A., A. Ruzin, H. F. Ross, N. Kurepina, and R. P. Novick. 1998. The gene for toxic shock toxin is carried by a family of mobile pathogenicity islands in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 29:527-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Löfdahl, S., J.-E. Sjöström, and L. Philipson. 1981. Cloning of restriction fragments of DNA from staphylococcal bacteriophage φ11. J. Virol. 37:795-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nesin, M., P. Svec, J. R. Lupski, G. N. Godson, B. Kreiswirth, J. Kornblum, and S. J. Projan. 1990. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of chromosomally encoded tetracycline resistance determinant, tetA(M), from a pathogenic, methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:2273-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novick, R. 1967. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology 33:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novick, R., G. K. Adler, S. J. Projan, S. Carleton, S. K. Highlander, A. Gruss, S. A. Khan, and S. Iordanescu. 1984. Control of pT181 replication I. The pT181 copy control function acts by inhibiting the synthesis of a replication protein. EMBO J. 3:2399-2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novick, R. P. 1991. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 204:587-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novick, R. P., I. Edelman, and S. Lofdahl. 1986. Small Staphylococcus aureus plasmids are transduced as linear multimers that are formed and resolved by replicative processes. J. Mol. Biol. 192:209-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novick, R. P., E. Murphy, T. J. Gryczan, E. Baron, and I. Edelman. 1979. Penicillinase plasmids of Staphylococcus aureus: restriction-deletion maps. Plasmid 2:109-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novick, R. P., and M. H. Richmond. 1965. Nature and interactions of the genetic elements governing penicillinase synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 90:467-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novick, R. P., H. F. Ross, S. J. Projan, J. Kornblum, B. Kreiswirth, and S. Moghazeh. 1993. Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 12:3967-3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Callaghan, C. H., A. Morris, S. M. Kirby, and A. H. Shingler. 1972. Novel method for detection of β-lactamases by using a chromogenic cephalosporin substrate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1:283-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Projan, S. J., S. Carleton, and R. P. Novick. 1983. Determination of plasmid copy number by fluorescence densitometry. Plasmid 9:182-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruzin, A., J. Lindsay, and R. P. Novick. 2001. Molecular genetics of SaPI1—a mobile pathogenicity island in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 41:365-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Schmetterer, G., C. P. Wolk, and J. Elhai. 1986. Expression of luciferases from Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio fischeri in filamentous cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 167:411-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trieu-Cuot, P., and P. Courvalin. 1983. Nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus faecalis plasmid gene encoding the 3′5"-aminoglycoside phosphotransferase type III. Gene 23:331-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, P.-Z., and R. P. Novick. 1987. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the β-lactamase gene from the Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258 in Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 169:1763-1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, P.-Z., S. J. Projan, K. R. Leason, and R. P. Novick. 1987. Translational fusion with a secretory enzyme as an indicator. J. Bacteriol. 169:3082-3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wieland, K. P., B. Wieland, and F. Gotz. 1995. A promoter-screening plasmid and xylose-inducible, glucose-repressible expression vectors for Staphylococcus carnosus. Gene 158:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]