Abstract

Background

Intravitreal injections are standard of care today and have the potential to change the anatomy of the anterior segment of the eye. This research was undertaken to evaluate the changes in anterior segment anatomy after intravitreal anti vascular endothelial growth factor (anti VEGF) injections.

Methods

We conducted a prospective interventional case series at a quaternary care center where patients undergoing intravitreal injection had pre and post injection ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) and intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement after intravitreal anti VEGF injection of 0.05 ml volume.

Results

75 eyes of 75 patients as per inclusion criteria were studied. A transient rise in IOP post intravitreal injection was found immediately after the injection. The mean rise from baseline was 17 mmHg immediately after injection and IOP returned to normal within 30 min in all cases. Angle measurement done as per established techniques revealed no significant changes in the angles and anterior chamber.

Conclusion

Intravitreal anti VEGF injections had no readily apparent short term concerns. IOP rise was transient and no case was found to have IOP high enough to cause concern for interruption of the optic nerve perfusion or statistically significant narrowing of the anterior chamber angle.

Keywords: Anterior chamber, Intraocular pressure, Intravitreal, Ultrasound biomicroscopy, Anti vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and other aetiologies of choroidal neovascularisation (CNV). Inhibition of VEGF with various drugs such as Pegaptanib, Ranibizumab and Bevacizumab, is an effective treatment for these and other vascular conditions.1

Bevacizumab (Avastin, Roche) is a full-length antibody that has the ability to bind all VEGF isoforms and was developed initially for therapy of colon cancer. Bevacizumab is a humanised recombinant IgG monoclonal antibody that acts by inhibiting VEGF, while Ranibizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody Fab fragment (IgG1). Ranibizumab (Lucentis, Novartis) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in AMD.2 Bevacizumab is also commonly used, although as an off-label treatment for AMD.3 Both these drugs are in widespread use today and have comparable efficacy.

It is reported that intravitreal injections can cause a rise in intraocular pressure due to the volume of drug injected as well as the specific characteristics of the injected chemical.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 It was our assessment that some of the previously used techniques used to assess the rise in IOP and anterior segment anatomy, in these reports, were not the ideal techniques that could have been used. We aimed to further clarify the effect of intravitreal injection of anti VEGF agents upon intraocular pressure (IOP) and anterior chamber structure using a previously validated technique of Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM).11, 12, 13

Materials and methods

We conducted a prospective study of 79 eyes of 79 patients treated with off-label intravitreal Bevacizumab for various indications. This prospective study had institutional ethics committee approval. Informed consent, particularly in regard to the off-label use and the potential for side effects known to occur with intravitreal administration of Bevacizumab, was obtained from all patients. All patients scheduled to have intravitreal anti VEGF injections for the first time were included provided they consented and had a pre injection ultrasound biomicroscopy (Marvel Ultrasound B scan and UBM, Appasamy, Chennai, India) scan. Patients with distinct history of myocardial infarction or stroke were excluded from the study. Only one eye of any patient was included in the study.

The intravitreal dose of Bevacizumab injected was 1.25 mg/0.05 ml. Bevacizumab was drawn into a 1 ml tuberculin syringe with a 30-gauge needle under complete aseptic precautions in the operation theater. All injections were given by a standard technique wherein, under topical anesthesia, the drug was injected in the inferotemporal quadrant ensuring the visibility of the needle in a dilated pupil. This was followed by an indirect ophthalmoscopy to rule out any bleeding or inadvertent damage and to check optic nerve perfusion. Topical antibiotics were given for 3 days after injection. Intravitreal injection was given 3 mm away from the limbus in pseudophakic eyes and 3.5 mm away from pars plana in phakic eyes. None of our patients was aphakic.

The patients were examined pre- injection in the operation theater where IOP was measured with a Tonopen (Tonopen XL Reichert Technologies, USA). After cleaning and draping, the pre-injection UBM was done using sterile saline. Then, 0.05 ml of intravitreal bevacizumab was given as described. IOP was taken immediately after the procedure after changing the Tonopen sterile cover. Post injection UBM was performed 5 min after the Tonopen measurement, under strict sterile aseptic precautions and a water immersion cup while the patient was still draped. Repeat IOP was measured after 10 min and after 30 min by non contact tonometer. A non contact method was used to minimize using the contact method (Tonopen) multiple times in the immediate post-injection period UBM was repeated after one month to look for any persisting changes in anterior segment parameters.

Measurement of UBM parameters: The following parameters were measured:

-

1.

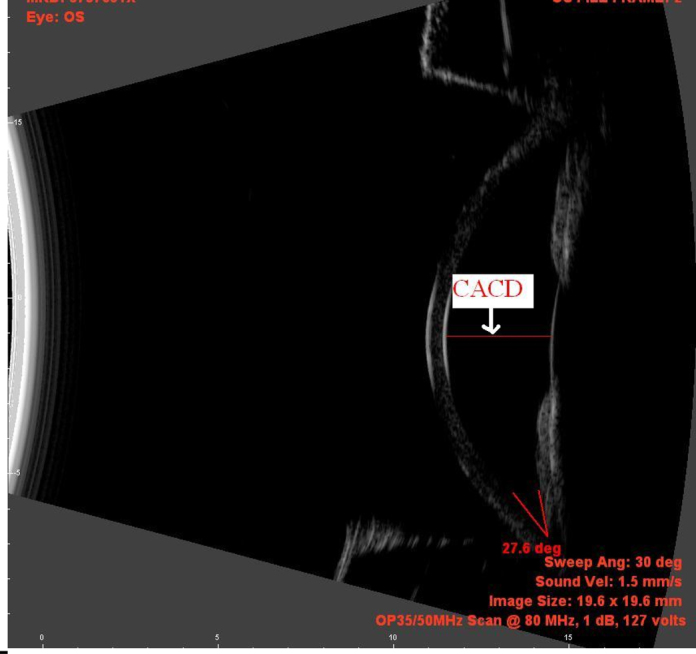

Central anterior chamber depth (CACD): Measured by drawing a perpendicular line from the center of the cornea at the level of the endothelium and extending till the anterior capsule of the lens. Measurements were read off the calipers on the instrument (Fig. 1).

-

2.

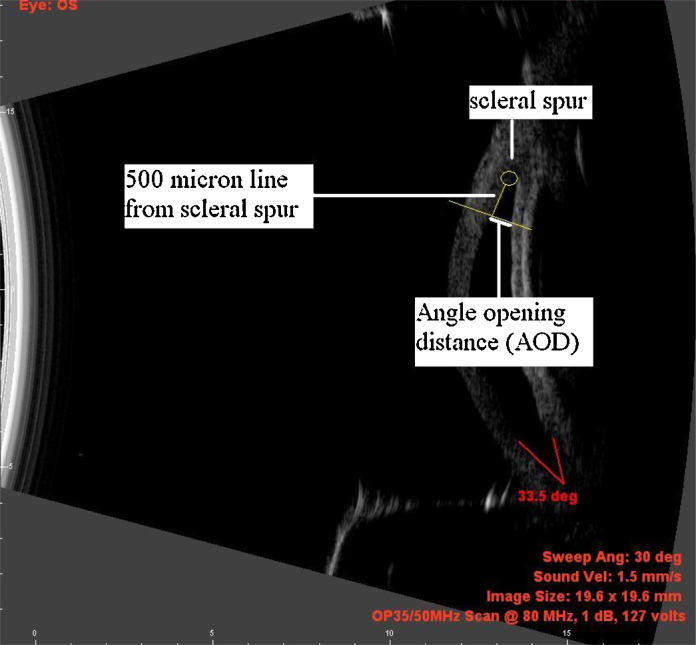

Angle opening distance (AOD): Measured by drawing a 500 μm line parallel to the endothelium starting at the scleral spur and extending toward the central cornea. At the 500 μm point, another line was drawn perpendicular to that point and the distance measured between the corneal endothelium and the point where the perpendicular crossed the peripheral iris (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Measurement of Central anterior chamber depth.

Fig. 2.

Measurement of Angle opening distance.

Statistical analysis

Data for all patients were entered into a database. Statistical analysis was performed using MS Excel software. Frequency and descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. The main outcome measurements were intraocular pressure pre and post injection at various time points, for which the repeated measures ANOVA was used. The anterior chamber parameters used were the CACD and peripheral anterior chamber depth as measured by the AOD on UBM.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age ± SD of the patients was 58.88 ± 11.67 yrs, range was 28–80 yrs. Of the patients finally reported, 58 patients were male and 17 were female. 44 right eyes were injected and 31 left eyes were injected. 40 were pseudophakic and 35 were phakic. Pre injection diagnoses were mainly choroidal neovascular membranes, diabetic macular edema or venous occlusion. 79 eyes were initially studied, 4 patients had incomplete data and were excluded from the study leading to a total of 75 eyes.

IOP parameters

Table 1 reports the mean ± std deviation values of IOP at time intervals of 0, 5, 10 and 30 min after intravitreal injection of 0.05 ml Bevacizumab. Repeated measures ANOVA for comparing the various groups comparing the baseline IOP to the IOP at various times was carried out. The F statistic was calculated. F critical {F0.05 (370, 74)} was 2.48 and the calculated F statistic was 288.2, leading to a rejection of the null hypothesis. This indicated that there was a highly significant difference between the various groups. However, despite the initial rise of IOP, all measurements declined to less than 30 mmHg by 30 min. The maximum IOP at various time points was 21, 49, 35, 33 and 22 mmHg at pre injection, 0, 5, 10 and 30 min respectively.

Table 1.

Change in IOP after intravitreal anti VEGF injection.

| Column no | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline | Baseline IOP | Immediately post inj | Diff (2-1) | At 5 min | Diff (4-1) | At 10 min | Diff (6-1) | At 30 min | Diff (8-1) |

| Mean | 15.17 | 32.45 | 17.28 | 27.96 | 12.79 | 25.21 | 10.04 | 17.03 | 1.85 |

| Median | 15.00 | 32.00 | 16.00 | 28.00 | 13.00 | 25.00 | 10.00 | 17.00 | 1.00 |

| Max | 21.00 | 49.00 | 35.00 | 36.00 | 23.00 | 33.00 | 20.00 | 22.00 | 8.00 |

| Min | 10.00 | 24.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 3.00 | 18.00 | −2.00 | 11.00 | −5.00 |

| St dev | 3.15 | 4.99 | 5.65 | 3.58 | 4.82 | 4.39 | 5.42 | 3.18 | 2.75 |

The columns labeled “Diff” give the values for change in IOP from baseline to the time point in the preceding column. For example, column number 3 gives the mean ± std deviation of the change in IOP from baseline (i.e. column 1) to immediately post injection (i.e. column 2).

UBM parameters

Table 2 describes the absolute values (in mm) and also the changes in the central AC depth (CACD) and the AOD at three time points i.e. pre injection, 5 min after injection and one month after injection. A repeated measures ANOVA was performed. F critical {F0.05 (2,148)} was 3.09 and the calculated F statistic for CACD was 0.71. Similarly, for PACD, F critical {F0.05 (2,148)} was 3.09 and the calculated F statistic was 2.41. Therefore, for both CACD and PACD, the null hypothesis, stating that there is no difference between groups, was accepted.

Table 2.

UBM parameters (mm) after intravitreal injection.

| Pre op CACD | Pre op AOD | Post op 5 min CACD | Post op 5 min AOD | Post op 1 mth CACD | Post op 1 mth AOD | Diff preop to 5 min CACD | Diff preop to 5 min AOD | Diff preop to 1 mth CACD | Diff preop to 1 mth AOD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.66 | 0.35 | 2.70 | 0.35 | 2.70 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.01 |

| Median | 2.59 | 0.34 | 2.59 | 0.36 | 2.64 | 0.34 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.02 |

| Max | 4.81 | 0.45 | 4.67 | 0.46 | 4.61 | 0.43 | 0.94 | 0.17 | 0.84 | 0.18 |

| Min | 2.20 | 0.25 | 1.71 | 0.25 | 2.28 | 0.24 | −0.80 | −0.17 | −1.22 | −0.17 |

| St dev | 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.08 |

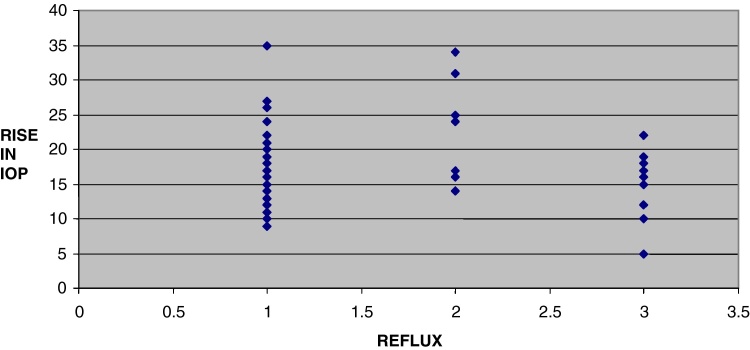

Effect of drug (vitreous) reflux is indicated in Fig. 3 wherein a value of 1 indicates no reflux, 2 indicates minimal reflux and 3 indicates definite reflux. There is an indication of a trend toward less IOP rise in cases with definite reflux.

Fig. 3.

Scatter plot of drug reflux vs rise in IOP.

Adverse effects

There were no instances of endophthalmitis or increased post injection inflammation of any degree. No patient received pre or postoperative anti glaucoma medication at any time point and there was no lens injury noted in any of the phakic patients.

Discussion

The use of intravitreal anti VEGF agents has been revolutionary in the field of vitreoretinal practice and these agents are now used in multiple conditions in all regions of the world. With the use of these agents came the realization that intraocular pressure changes can occur even with the use of minute quantities of drugs in the range of 0.1–0.05 ml. Our study corroborates the previous literature that IOP decreases to safe levels by 30 min after an initial rise and there is no immediate or long term change in anterior segment parameters. The use of UBM for these measurements along with the Tonopen lends added credibility to the findings as this has not been done earlier.

Retrospective studies that reported IOP elevation after intravitreal anti VEGF injections have all concluded that in the short term there is a rapid rise in the IOP, which normalizes in 30 min. Bakri et al.8 compared IOP elevation after intravitreal injection of 0.3 mg Pegaptanib, 4 mg Triamcinolone and 1.25 mg Bevacizumab. Review of patient records reported that approximately 87% of eyes administered each drug recorded an IOP of less than 35 mmHg 10 min after injection. Of the forty two eyes receiving intravitreal triamcinolone, three were treated with antiglaucoma medication. No patients treated with intravitreal Pegaptanib or bevacizumab received IOP-lowering drops. This and other retrospective studies corroborate our findings, although our study was of a prospective nature.

There have also been prospective studies specifically addressing the issue of short term IOP elevation that are similar to our study. Höhn et al14 studied the effect of different methods of administering intravitreal 0.05 ml Ranibizumab in the supine position. Thirty one of their patients received injections by a standard technique, and fourteen by a technique termed ‘tunneled sclera technique’. IOP was measured immediately pre-and postoperatively by Schiøtz tonometry, and the quantity of subconjunctival reflux of vitreous was assessed using a semi-quantitative scale. IOP was seen to increase to a significant degree in an appreciable number of patients in the immediate post injection period. They concluded that this increase was correlated with the type of injection technique used and further stated that tunneled scleral technique of injection resulted in higher IOP. Although the results of the study conform to ours in that the IOP changes were similar, we did not specifically study the effect of different injection techniques. Also, we used a Tonopen for the intraoperative measurement and non contact tonometer for the post operative measurement.

In contrast to the above study, Knecht et al.15 also compared tunneled scleral injection and straight injection technique. They additionally studied short-term IOP variation, patient discomfort and presence and quantity of vitreous reflux. Occurrence of reflux and amount of vitreous reflux were noted to be significantly higher with the straight scleral injection technique. They detected no significant difference in pain rating scale scores or IOP increase between both groups. They concluded that tunneled intravitreal injection may be a better choice for low-volume intravitreal injection (0.05 ml). They also proposed that less vitreous reflux with tunneled intravitreal injection may result in less post injection drug loss. The results of this study contradict the findings of Hohn et al.

Some prospective studies have been carried out using the Tonopen rather than the Schiøtz tonometer. The Tonopen has better correlation with the gold standard of Goldman tonometer than Schiøtz tonometry. Falkenstein et al16 carried out a prospective study that closely approximated ours as far as the study of IOP is concerned. They also used the Tonopen but included patients who had repeated injections of bevacizumab and carried out IOP measurements at 3, 10 and 15 min after injection. These inclusion criteria are in contrast to ours. However, their results and conclusions were similar to our study.

Sharei et al.17 studied the changes of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injection Ranibizumab (0.05 ml). Ranibizumab was injected in forty five patients with AMD. Schiøtz tonometry was performed immediately preoperatively and postoperatively. This was repeated after 3 and 10 min in a supine position. IOP decreased spontaneously by the first 3 min after injection by 12.6 ± 6.0 mmHg and by 21 ± 9.4 mmHg at the 10 min end point They stated that eyes without subconjunctival vitreous reflux had more IOP increase than eyes that had any reflux. These results are similar to those reported by Hohn et al.

We also tried to assess the effect of subconjunctival reflux on the IOP but found that although the data suggests that the presence of drug reflux leads to a lesser magnitude of IOP change, the number of patients in our study who had drug reflux was only 10 out of 75; hence no firm conclusions could be drawn.

Sustained elevations in intraocular pressure have been reported especially with repeated intravitreal injections; however, this study specifically investigated only the short-term effects of a single intravitreal injection.

Researchers have also reported upon the effect of intravitreal injection on the dimensions of the eye, similar to the conduct of our study. Goktas et al.18 reported on short-term effects of intravitreal Ranibizumab on intraocular pressure and axial length measurements. Anterior chamber depth and axial length were measured with IOL Master and IOP was measured with the non-contact tonometer before and after the injection at 5 min, 30 min and 1 day intervals. No statistically significant changes in axial length and anterior chamber depth parameters were seen. No correlation was found between biometric parameters and IOP 5 min after injection. Assessment of control group by identical protocol revealed no statistically significant differences. They concluded that axial length and anterior chamber depth do not seem to be altered by this volume of intravitreal injection and the transient post injection increase of IOP seems to be unrelated to biometric parameters. The conclusions drawn in this study and its methodology are closest to our study; however the differences are in the techniques used. We have used the UBM and the Tonopen while these authors have used the IOL master and non contact tonometer. The reason for using the UBM despite it being a contact method was that we also wanted to assess the peripheral AC depth by measuring the AOD to assess whether there was any crowding of the angle that could account for the increase in IOP. The IOL master does not allow assessment of peripheral AC depth whereas the UBM does.

Singer et al19 tried to correlate the pre injection angle recess (AR) width with post injection rise of intraocular pressure after injection 0.1 ml of triamcinolone acetonide. Angle dimensions were assessed by anterior segment OCT prospectively over 5 years. IOP was measured up to 6 months from the date of injection. They aimed to establish whether this parameter would predict the degree of rise of IOP in the post injection period and thus indicate the presence of high-risk cases. Twenty-six eyes were studied, with minimal response in 42% eyes, moderate response in 42%, and severe increase in 15%. The mean ± SEM AR widths reported were: 326 ± 31.5 μm, 281 ± 22.0 μm, and 138 ± 20.3 μm, respectively. Statistically significant AR width differences were noted between moderate and severe response groups and also between severe and minimal response groups. This indicates that there may be measurable relationship between AR width and IOP rise with narrower AR widths predicting grater IOP rise after injection. The findings of the above study need to be replicated and could facilitate detection of high-risk cases prior to intravitreal injection. However, the effect with a different volume of Bevacizumab or Ranibizumab needs to be studied and is a potential future study.

Our study has certain limitations. Firstly, we elected to use the Tonopen when the patient was draped and under full aseptic precautions and subsequently the IOP was measured later by the non contact tonometer. This resulted in comparison of two different measurement techniques in the intra and postoperative periods. This methodology was mandated by ethical considerations to minimize, to the greatest extent possible, any unnecessary exposure to contact methods in the postoperative period. However, we found no difference in the trends noted when this methodology was adopted. Use of a non contact method to measure IOP intraoperatively was not possible. Secondly, since we used a contact method for the UBM, we did not measure the anterior segment parameters repeatedly after the injection. There was only a 5 min post injection assessment and then an assessment at 30 min. Hence it is possible that we missed some changes in the anterior segment that occurred between 5 min post injection and 30 min post injection. We felt this period was important since repeated measurements of parameters would have allowed us to correlate the temporal changes in anterior segment with the IOP, which usually decreased in 30 min. Again, this would have involved an increased risk of infection for the patient and was not done for ethical reasons.

The strength of our study is the use of the UBM and Tonopen. These are validated and standardized techniques and form the gold standard for measurements in supine patients providing information not available by using non contact methods. Also, the immediate pre and post injection measurements were done with patients in the same supine position, thus providing for consistency of results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, intravitreal injection of 0.05 Bevacizumab is accompanied by a short-term clinically and statistically significant rise in intraocular pressure. extent of this rise is usually not sufficient to exceed the perfusion pressure of the optic nerve and IOP greater than 30 mmHg was sustained for less than 30 min in all patients. The influence of vitreous reflux cannot be commented upon with certainty; however there may be some indication that individuals with no reflux upon injection may have higher IOP post injection. There was no clinically or statistically significant change in anterior chamber parameters as measured with the ultrasound biomicroscope. A single intravitreal injection of Bevacizumab is safe and well tolerated in patients and does not lead to changes in the intraocular pressure or anterior chamber depth that can lead to ocular damage in the short term.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on Armed Forces Medical Research Committee Project No. 4105/2010 granted and funded by the office of the Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services and Defence Research Development Organization, Government of India.

References

- 1.Amoaku W.M.K. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists interim recommendations for the management of patients with age-related macular degeneration. Eye. 2008;22(6):864–868. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara N., Damico L., Shams N., Lowman H., Kim R. Development of Ranibizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antigen binding fragment, as therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2006;26(8):859–870. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000242842.14624.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrara N., Hillan K.J., Gerber H.-P., Novotny W. Case history: discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(May (5)):391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu H., Chen T.C. The effects of intravitreal ophthalmic medications on intraocular pressure. Semin Ophthalmol. 2009;24(January (2)):100–105. doi: 10.1080/08820530902800397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenfeld P.J., Brown D.M., Heier J.S. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(October (14)):1419–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu L., Martínez-Castellanos M.A., Quiroz-Mercado H. Twelve-month safety of intravitreal injections of bevacizumab (Avastin®): results of the Pan-American Collaborative Retina Study Group (PACORES) Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;246(August (1)):81–87. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0660-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh R.S.J., Kim J.E. Ocular hypertension following intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(December (12)):949–956. doi: 10.1007/s40266-012-0031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakri S.J., Pulido J.S., McCannel C.A., Hodge D.O., Diehl N., Hillemeier J. Immediate intraocular pressure changes following intravitreal injections of triamcinolone, pegaptanib, and bevacizumab. Eye (London) 2009;23(January (1)):181–185. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benz M.S., Albini T.A., Holz E.R. Short-term course of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(July (7)):1174–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gismondi M., Salati C., Salvetat M.L., Zeppieri M., Brusini P. Short-term effect of intravitreal injection of Ranibizumab (Lucentis) on intraocular pressure. J Glaucoma. 2009;18(December (9)):658–661. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31819c4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorairaj S., Liebmann J.M., Ritch R. Quantitative evaluation of anterior segment parameters in the era of imaging. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;105:99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tello C., Liebmann J., Potash S.D., Cohen H., Ritch R. Measurement of ultrasound biomicroscopy images: intraobserver and interobserver reliability. IOVS. 1994;35(August (9)):3549–3552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urbak S.F., Pedersen J.K., Thorsen T.T. Ultrasound biomicroscopy. II. Intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility of measurements. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1998;76(October (5)):546–549. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Höhn F., Mirshahi A. Impact of injection techniques on intraocular pressure (IOP) increase after intravitreal Ranibizumab application. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248(October (10)):1371–1375. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1382-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knecht P.B., Michels S., Sturm V., Bosch M.M., Menke M.N. Tunnelled versus straight intravitreal injection: intraocular pressure changes, vitreous reflux, and patient discomfort. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa) 2009;29(September (8)):1175–1181. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181aade74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falkenstein I.A., Cheng L., Freeman W.R. Changes of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin) Retina. 2007;27(8):1044–1047. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3180592ba6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharei V., Höhn F., Köhler T., Hattenbach L.-O., Mirshahi A. Course of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injection of 0.05 mL Ranibizumab (Lucentis) Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(February (1)):174–179. doi: 10.1177/112067211002000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goktas A., Goktas S., Atas M., Demircan S., Yurtsever Y. Short-term impact of intravitreal Ranibizumab injection on axial ocular dimension and intraocular pressure. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32(1):23–26. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2012.696569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer M.A., Groth S.L., Sponsel W.E. Association of OCT angle recess width with IOP response after intravitreal triamcinolone injection. Retina. 2013;33(February (2)):282–286. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182675c72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]