Abstract

The yeast cyclins Cln1 and Cln2 are very similar in both sequence and function, but some differences in their functionality and localization have been recently described. The control of Cln1 and Cln2 cellular levels is crucial for proper cell cycle initiation. In this work, we analyzed the degradation patterns of Cln1 and Cln2 in order to further investigate the possible differences between them. Both cyclins show the same half‐life but, while Cln2 degradation depends on ubiquitin ligases SCFG rr1 and SCFC dc4, Cln1 is affected only by SCFG rr1. Degradation analysis of chimeric cyclins, constructed by combining fragments from Cln1 and Cln2, identifies the N‐terminal sequence of the proteins as responsible of the cyclin degradation pattern. In particular, the N‐terminal region of Cln2 is required to mediate degradation by SCFC dc4. This region is involved in nuclear import of Cln1 and Cln2, which suggests that differences in degradation may be due to differences in localization. Moreover, a comparison of the cyclins that differ only in the presence of the Cln2 nuclear export signal indicates a greater instability of exported cyclins, thus reinforcing the idea that cyclin stability is influenced by their localization.

Keywords: cell cycle, Cln1, Cln2, cyclin, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, SCF ubiquitin ligase

Abbreviations

- CDK

cyclin‐dependent kinase

- CKI

cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor

- CPD

Cdc4 phosphodegron

- HA

human influenza hemagglutinin epitope

- NLS

nuclear localization signal

- PEST

domain rich in proline, glutamic acid, serine, threonine

- SCF

Skp1‐cullin‐F‐protein ubiquitin ligase complex

Cell cycle progression is governed by the sequential activation of different cyclin‐dependent kinase (CDK) complexes. For the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, nine different cyclins (Cln1–3 and Clb1–6) activate the Cdc28 protein, the only yeast CDK which performs an essential function in cell cycle progression (reviewed in 1, 2). The level of the associated cyclin and CDK inhibitors (CKI) determines the kinase activities that are present at a given time. Two molecular mechanisms, gene transcription and protein degradation, control these key cell cycle regulators. The coordinated expression of different sets of genes, organized in transcriptional waves along the cell cycle, is a very common strategy in cell cycle control in all eukaryotes. These genes are typically involved in specific cell cycle processes and their maximum expression coincides with the time that their products are required. These transcriptional waves are regulated by transcription factors whose expression is usually also cell cycle regulated in a way that help to organize the waves of expression 3, 4, 5. All the cyclins associated with Cdc28 CDK are periodically expressed. In the case of CLN1 and CLN2 genes, both are expressed during the G1/S transition by the transcription factor SBF 6, 7, 8. The second major mechanism involved in the control of the cellular levels of cell cycle regulators is proteolysis by means of ubiquitination and degradation in the proteasome 9, 10, 11, 12. Protein ubiquitination is carried out by the successive action of ubiquitin‐activating (E1), ubiquitin‐conjugating (E2) and ubiquitin‐protein ligase (E3) enzymes 13. Ubiquitin ligases mediate the transfer of the ubiquitin molecule from the E2 enzyme to the ε‐amino of a lysine at the target proteins. Two ubiquitin ligases play an important role in the cell cycle regulation: Skp1‐cullin‐F‐box protein (SCF), which is critical for the G1/S transition and anaphase‐promoting complex (APC), which performs an essential function in mitosis 14, 15, 16.

SCF is involved mainly in the control of the G1/S transition through the degradation of G1 cyclins and CKI 17, 18, 19, 20. However, it can also participate in other cell cycle phases 21. The SCF complex consists in four subunits: Skp1, Cdc53, Rbx1 and an adapter protein with an F‐box. The Rbx1 subunit interacts with the ubiquitin‐conjugating enzyme, Cdc34 in this case, whereas the F‐protein is responsible for substrate recognition. Three F‐proteins have been found to be involved in the degradation of cell cycle regulators: Cdc4, Grr1 and Met30. They present protein–protein interaction domains, such as leucine‐rich repeats LRR for Grr1 or a WD40 domain in the case of Cdc4 and Met30 22. The presence of distinct F‐protein subunits in the complex directs SCF activity to different targets. However, some overlapping sets of substrates may exist since, recently, it has been described that G1 cyclin Cln3 is targeted by both ubiquitin ligases SCFCdc4 and SCFGrr1 23. The other G1 cyclins, Cln1 and Cln2, are also important targets of SCF. They are highly unstable proteins with reported half‐lives under 15 min 20, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29. Cln2 and Cln1 are strongly stabilized in a grr1 mutant strain 20 and both cyclins bind to Grr1 30. Moreover, the transfer of the C‐terminal region of Cln2 to heterologous proteins confers protein instability mediated by SCFGrr1 31. For this reason, it is assumed that SCFGrr1 is the ubiquitin ligase involved in Cln1 and Cln2 degradation. However, Cln1 and Cln2 bind to SCFCdc4 in vitro and, in fact, contradictory results have been obtained for the effect of cdc4 mutation on Cln2 stability 23, 32, 33, 34.

Instability of proteins depends on a degron motif, which is recognized by the ubiquitin ligase. In the case of SCF, recognition by the F‐protein requires the presence of phosphorylated epitopes in the degron. Sic1 has served as a model substrate, so the mechanics of its recognition by Cdc4 are understood in detail 22, 35, 36, 37, 38. This model allowed the description of the consensus Cdc4 phosphodegron (CPD) sites present in SCFCdc4 substrates. The Cdc4 recognition mechanism is highly tunable, and the number and nature of the CPD sites and the targeting kinases 22. The precise Grr1 phosphodegron and how it may differ from the CPD have yet to be precisely defined. PEST motifs (rich in proline, glutamic acid, serine and threonine) have been described in SCFGrr1 substrates, such as G1 cyclins Cln1 and Cln2, as being the regions responsible for their instability. In the case of Cln2, deletion of little more than the PEST region (from 373 to 409 amino acids) renders a protein significantly more stable than the wild‐type. Nonetheless, additional stability is achieved by deletions that remove the entire carboxyl terminus (from 373 to 545), indicating that the sequences around the PEST sequence are also involved in the control of Cln2 stability 26. This conclusion is supported by the converse experiment in which the transfer of Cln2376–545 confers high instability to a heterologous protein, whereas a smaller region has a milder effect 26, 31. Similarly, a deletion of Cln1 including a portion of its PEST region and its carboxyl terminus (Cln1266–546), produces a stable protein 20.

Cln1 and Cln2 are the most similar cyclins in yeast. They show a 57% sequence identity, which increases up to 72% in the N‐terminal region containing the cyclin box domain. The extensive work carried out on these cyclins revealed that both take part in many common functions at the G1/S transition 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48. All these results led to the notion that Cln1 and Cln2 are equivalent cyclins. However, in addition to the numerous studies that highlight Cln1 and Cln2 similarities, several functional differences between them have also been described 49, 50, 51, 52, 53. In some cases, the functional distinction seems to be caused by quantitative differences at the expression level. More recently, cyclin‐specific docking motifs in target proteins that bind preferentially to Cln2 54, and a nuclear export mechanism present only in Cln2 that contributes to the functional distinction between Cln1 and Cln2 55, have been described. As regards Cln1,2 degradation, most of the studies have been performed with antibodies that recognize either both cyclins or Cln2 alone, and many of the results reported for Cln2 have been extended to Cln1. To complete a comparative study of Cln1 and Cln2, the present study attempts to analyze the degradation of both cyclins in order to investigate new differences between them.

Materials and methods

The yeast strains used in this study are W303‐1a (MATa ade2‐1 trp1‐1 leu2‐3,112 his3‐11,15 ura3‐52), cdc53 ts (MATa ade2‐1 trp1‐1 leu2‐3,112 his3‐11,15 ura3‐52 cdc53.1), cdc4 ts (MATa ade2‐1 trp1‐1 leu2‐3,112 his3‐11,15 ura3‐52 cdc4‐1) and JCY1539 (grr1::LEU2 in W303‐1a). Yeast cells were grown on synthetic dextrose medium supplemented as required. Centromeric plasmids pCLN1 and pCLN2 expressing HA‐tagged versions of Cln1 and Cln2, respectively, were a gift from Dr. M. Aldea. Centromeric plasmids expressing HA‐tagged chimeric cyclins or CLN1 and CLN2 genes under the control of the ADH1 promoter, were described in 55. Centromeric plasmids pNE104 and pNE108 expressing Cln2 fused to a canonical active or inactive NLS, respectively, were a gift from Dr. B. Futcher 56.

To evaluate cyclin stability, 50 μg·mL−1 cycloheximide was added to exponentially growing cells or cells incubated during 3 h at 37° as indicated. Samples were harvested at the indicated times and cyclin protein decay was analyzed by western blot as described previously 57. Antibodies used were anti‐HA 3F10 or 12C5A (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), anti‐Cln2 y‐115 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) and anti‐tubulin (Serotec, Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Bands were quantified with an ImageQuant™ LAS 4000mini biomolecular imager (GE Healthcare, Fairfield, CT, USA). At least three independent experiments were carried out for each cyclin/strain. In the case of thermosensitive degradation mutants, although we observed quantitative variations between experiments, the qualitative effect of each mutation in cyclin stability was consistently reproducible; the results shown in figures are representative results of the experiment.

Results

Analysis of Cln1 and Cln2 stability

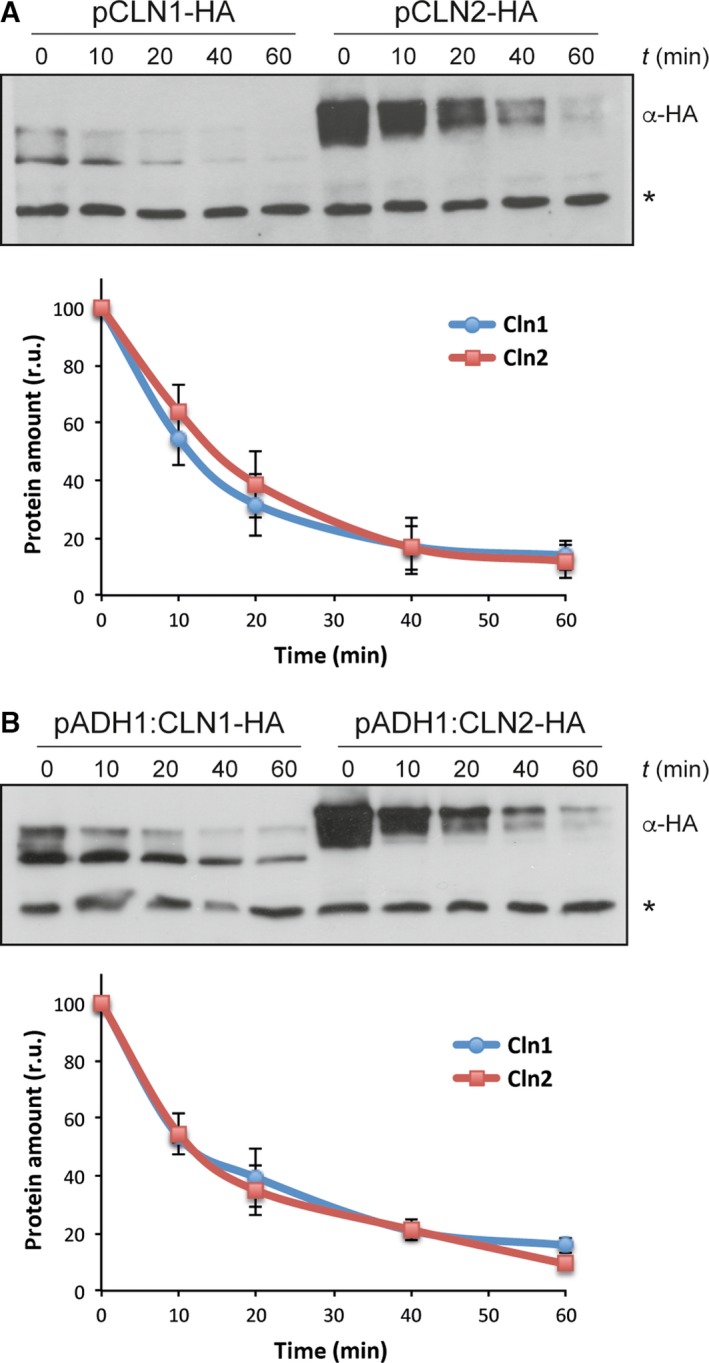

To date, no parallel assays of Cln1 and Cln2 protein degradation have been carried out. Therefore, we first compared the stability of the two cyclins separately. Translational shut‐off experiments were carried out, following protein decay after the addition of cycloheximide by western blot. The stability of Cln1 and Cln2 was analyzed in the wild‐type cells expressing HA‐tagged version of the proteins under the control of their own promoters or the ADH1 promoter (a noncell cycle‐regulated promoter to avoid secondary effects due to cell cycle alterations by cycloheximide treatment). As seen in Fig. 1, both proteins showed identical decay kinetics when expressed endogenously or ectopically. We can conclude that the stability of cyclins Cln1 and Cln2 is similar.

Figure 1.

Protein stability of cyclins Cln1 and Cln2. Exponentially growing cells of the wild‐type strain transformed with a centromeric plasmid expressing either a HA‐epitope tagged Cln1 or Cln2 protein at endogenous level (A) or overexpressed from the ADH1 promoter (B) were incubated in the presence of 50 μg·mL−1 cycloheximide. Cln1 and Cln2 protein levels were analyzed at the indicated time after the addition of cycloheximide by western blot. A nonspecific band labeled with an asterisk that cross‐react with the antibody is shown as loading control. Graph represents the relative amount of Cln1 and Cln2 proteins related to the nonspecific band.

Ubiquitin ligases involved in the degradation of Cln1 and Cln2

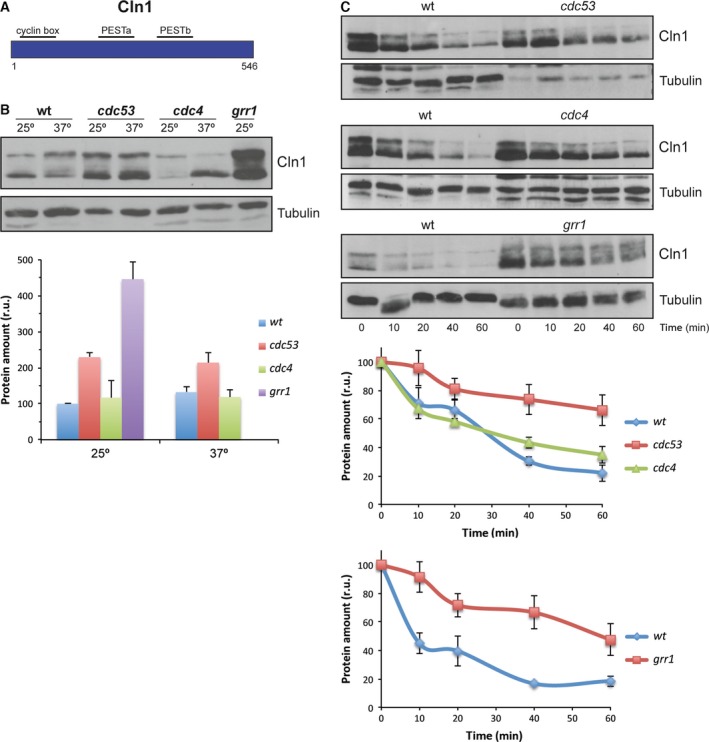

G1 Cln cyclins are degraded by the ubiquitin ligase SCF pathway. Substrate recognition depends on the F‐box protein of the complex. In the case of cyclins Cln1 and 2, Grr1, but not Cdc4, has been described to be the F‐protein involved in their degradation. However, these experiments jointly analyzed Cln1 and Cln2 or only analyzed Cln2. For this reason, the second aim of this work was to separately study Cln1 and Cln2 stability in mutant strains in the F‐proteins Grr1 and Cdc4 in order to determine whether there are differences in the requirements for a specific F‐protein between both cyclins. Thus, the mutant strains in Cdc4 or Grr1, as well as in the SCF‐cullin subunit Cdc53, were transformed with the plasmids expressing HA‐tagged Cln1 and Cln2, and the cyclin protein levels were compared to those of the wild‐type cells. CDC4 and CDC53 are essential genes, so thermosensitive mutant strains were used in these cases. The results obtained are shown in Figs 2 and 3. The Cln1 protein level sharply increased in the grr1 mutant strain. Importantly, no increase in Cln1 cellular content was detected for the cdc4 mutant cells at the restrictive temperature, suggesting that only Grr1 is involved in Cln1 degradation. To further investigate this possibility, we also analyzed Cln1 stability in the different mutant strains by translational shut‐off experiments. As shown in Fig. 2C, inactivation of Grr1 but not Cdc4 resulted in a marked stabilization of Cln1. All together, these results indicate that Cln1 is degraded by SCFGrr1.

Figure 2.

Analysis of Cln1 degradation in SCF ubiquitin‐ligase mutant strains. (A) Scheme of Cln2 cyclin. (B) Cells of the wild‐type (W303), cdc53, cdc4 and grr1 (JCY1539) strains transformed with a centromeric plasmid expressing a HA‐epitope tagged Cln1 protein at endogenous level were grown at 25° and transferred for 3 h at 37° in the case of cdc53 and cdc4 strains. Cln1 protein level was analyzed by western blot. Tubulin is shown as loading control. Graph represents the relative amount of Cln1 protein. (C) Same cells than in B were incubated in the presence of 50 μg·mL−1 cycloheximide. Cln1 protein level was analyzed at the indicated time after the addition of cycloheximide by western blot. Tubulin is shown as loading control. Graph represents the relative amount of Cln1 protein.

Figure 3.

Analysis of Cln2 degradation in SCF ubiquitin‐ligase mutant strains. (A) Scheme of Cln2 cyclin. (B, C) Protein level and degradation of Cln2 cyclin were analyzed as described in Fig. 2.

However, a different result was obtained for Cln2. The Cln2 levels increase in the cdc53 ts and cdc4 ts mutant strains at the restrictive temperature, as well as in the absence of Grr1 (Fig. 3B), suggesting that both Grr1 and Cdc4 are involved in Cln2 degradation. Consistently with these results, the translational shut‐off assays revealed protein stabilization in the absence of Cdc53, Cdc4 and Grr1 (Fig. 3C). Thus, our results reveal a difference in the degradation of both cyclins: while Cln1 is mostly degraded by SCFGrr1, Cln2 degradation depends on both SCFCdc4 and SCFGrr1.

The cyclin regions affecting degradation

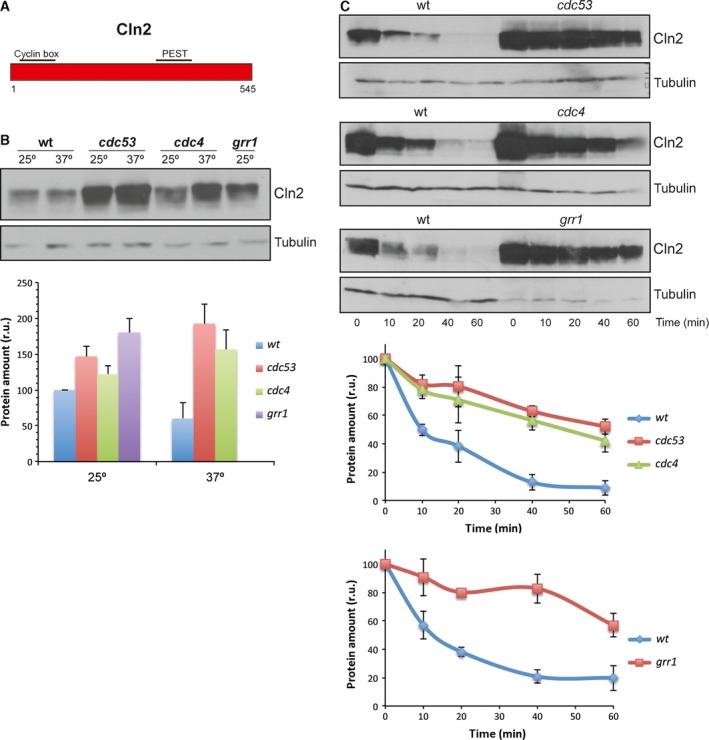

The use of different adaptor proteins in the degradation pathway may be due to different causes, possibly reflecting a difference in the function of the PEST sequences recognized by the F‐proteins. PEST sequences were identified in Cln1 and Cln2 58. These regions were also predicted by the PESTfind program (http://emboss.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/emboss/epestfind). Cln2 contained a PEST sequence between amino acids 371 and 403 with a predicted value of 6.99. Cln1 contained a PEST in a similar region, between amino acids 398 and 424 (PESTb), although it was predicted with a very low value (0.85); another PEST sequence between amino acids 234 and 275 (PESTa) was predicted in Cln1 with a value of 14.12, which was absent in Cln2. In order to determine the relevance of these PEST sequences or additional regions in cyclin degradation, the strategy used consisted in studying the degradation of chimeric cyclins obtained by the exchange of the equivalent regions between Cln1 and Cln2 55. The first question to be addressed was whether the PESTb of Cln1 was functional given its low prediction value. In order to answer this question, we analyzed the degradation of Chimera 2 (Cln21–299‐Cln1313–546). This chimera contained the N‐terminal region of Cln2 and the C‐terminal region of Cln1, so the PEST of Cln2 was exchanged for the PESTb of Cln1. The analysis of Chimera 2 stability showed that Chimera 2 was much more unstable than Cln1 and Cln2 (Fig. 4). This result supports the notion that the PESTb of Cln1 was functional and that, in fact, it could prove even more efficient than the corresponding Cln2 PEST.

Figure 4.

Protein stability of chimeric cyclins. Protein stability of chimeric cyclins was analyzed as described in Fig. 1.

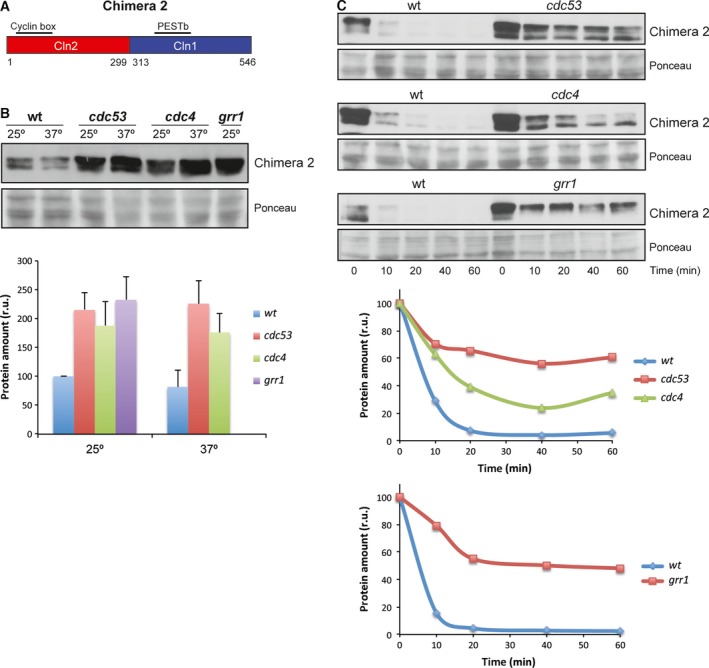

Next, we tested the protein level and the stability of the chimera in the SCF subunit mutants as described above in order to determine the machinery involved in its degradation. The cellular content of Chimera 2 increased in all the cdc53 ts, cdc4 ts and grr1 mutant strains (Fig. 5B). Consistently with this, the translational shut‐off assays exhibited a stabilization of Chimera 2 in all the mutants (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that both SCFGrr1 and SCFCdc4 mediated Chimera 2 degradation, similar to that observed for Cln2. The fact that the degradation pattern of Chimera 2 corresponded to Cln2, despite it contains the PESTb of Cln1, indicates that as far as the F‐proteins were concerned, Cln2 PEST and Cln1 PESTb are equivalent and that other factors acting outside the C‐terminal region determined the degradation pattern of the cyclin.

Figure 5.

Analysis of Chimera 2 degradation in SCF ubiquitin‐ligase mutant strains. (A) Scheme of Chimera 2 cyclin. (B, C) Protein level and degradation of Chimera 2 cyclin were analyzed as described in Fig. 2. Ponceau staining is shown as loading control.

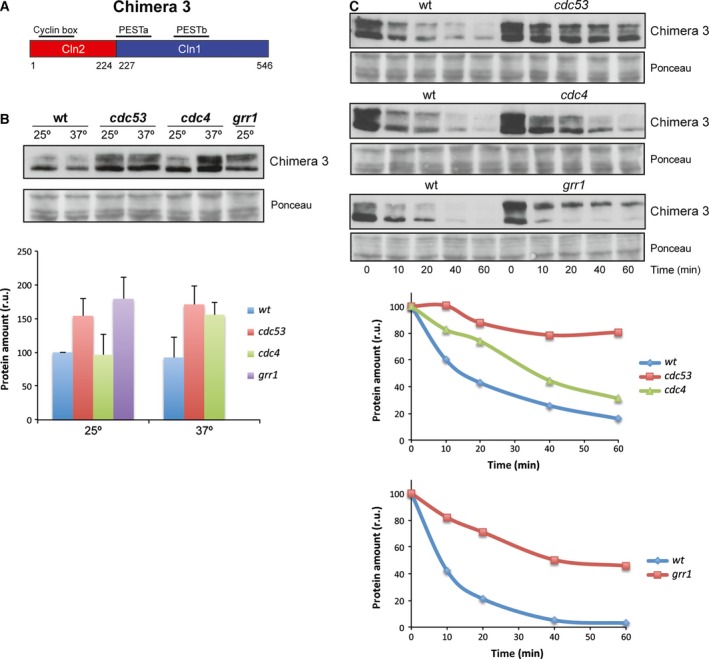

We also analyzed Chimera 3 (Cln21–224‐Cln1227–546) degradation. This chimera presented a shorter Cln2 N‐terminal region, and the PESTa and PESTb of Cln1. Chimera 3 stability was similar to that of Cln1 and Cln2 (Fig. 4). The protein level of Chimera 3 increased in the cdc53, cdc4 and grr1 mutant cells (Fig. 6B). This is consistent with the translational shut‐offs experiment results since Chimera 3 was stabilized in all the mutant strains as compared to the wild‐type (Fig. 6C). Thus, as occurred for Cln2 and Chimera 2, Chimera 3 would be degraded by both SCFGrr1 and SCFCdc4. This is apparently surprising because this chimera contained all the Cln1 sequences involved in cyclin degradation. However, its degradation pattern did not correspond to Cln1, but to Cln2. The only region of Cln2 that remained in Chimera 3 was the N‐terminal region from amino acids 1 to 224. Therefore this region, and not the PEST sequences, would be responsible for determining the degradation pattern of the cyclin allowing the cyclin to be degraded not only by SCFGrr1, but also by SCFCdc4.

Figure 6.

Analysis of Chimera 3 degradation in SCF ubiquitin‐ligase mutant strains. (A) Scheme of Chimera 3 cyclin. (B, C) Protein level and degradation of Chimera 3 cyclin were analyzed as described in Fig. 2. Ponceau staining is shown as loading control.

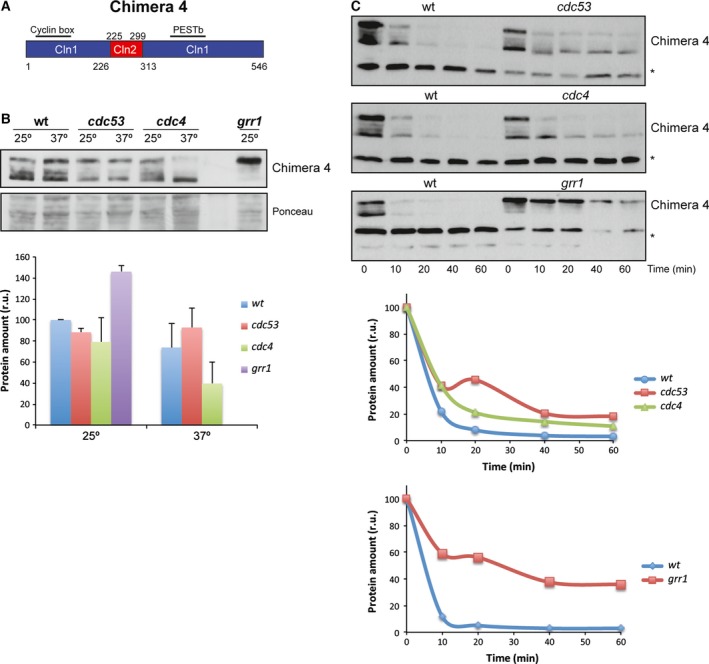

Finally, we used Chimera 4 (Cln11–226‐Cln2225–299‐Cln1313–546), derived from Cln1 by replacing an internal fragment from the equivalent region of Cln2 (Fig. 7A). Consequently, Chimera 4 lost Cln1 PESTa, so it only contained Cln1 PESTb. The analysis of Chimera 4 level in the different degradation mutant strains indicated that the protein level was roughly similar to wild‐type cells in the case of mutant cells cdc53 and cdc4. Conversely, Chimera 4 significantly increased in the absence of Grr1 (Fig. 7B). Once again, the translational shut‐off results were consistent with these observations since a significant stabilization of Chimera 4 was observed only in the case of the grr1 mutant strain (Fig. 7C). All these observations were similar to that observed with Cln1 and allowed us to conclude that Chimera 4 was degraded, as Cln1, mostly by SCFGrr1. The fact that Chimera 4 followed a degradation pattern characteristic of Cln1, whereas Chimera 2 followed that of Cln2, further reinforced the conclusion that the N‐terminal end of the cyclin was somehow involved in the control of its degradation. More specifically, the region of Cln2 from amino acids 1 to 224 allowed SCFCdc4 to control cyclin stability.

Figure 7.

Analysis of Chimera 4 degradation in SCF ubiquitin‐ligase mutant strains. (A) Scheme of Chimera 4 cyclin. (B, C) Protein level and degradation of Chimera 4 cyclin were analyzed as described in Fig. 2. Ponceau staining or a nonspecific band labeled with an asterisk that cross‐react with the antibody is shown as loading control.

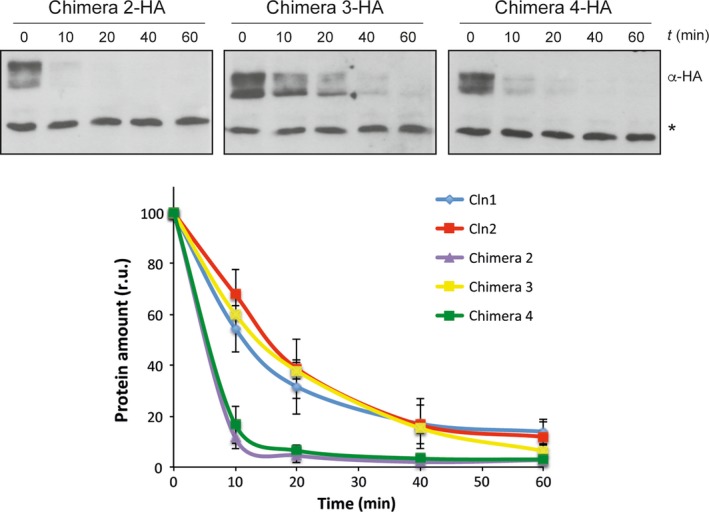

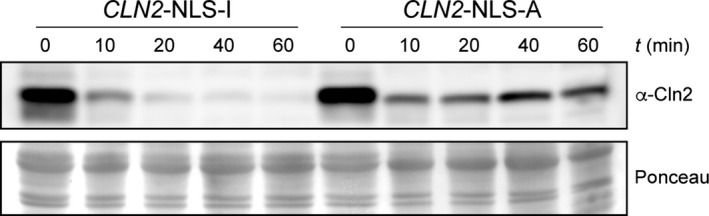

Furthermore, the analysis of the Chimera 4 degradation in wild‐type cells revealed that this cyclin was much more unstable than Cln1 (Fig. 4). The Cln2 fragment inserted in Chimera 4 contained a nuclear export signal 55. Hence, this result could indicate that cyclin stability might be affected by its subcellular location, so the nuclear export of the cyclin resulted in greater instability. To investigate this possibility, the stability of a version of Cln2 shifted to the nucleus due to the fusion of two copies of the SV40 nuclear localization signal 56, was analyzed. As it can be observed in Fig. 8, increasing Cln2 nuclear localization resulted in a significant stabilization of the protein. This result is consistent with the increased instability of Chimera 4 and strongly supports that these cyclins are more stable in the nucleus than in the cytosol.

Figure 8.

Protein stability of Cln2 protein with altered localization. Protein level of Cln2 cyclin fused to two copies of either active or inactive SV40 NLS was analyzed at the indicated time after the addition of cycloheximide by western blot. Ponceau staining is shown as loading control.

Discussion

Cyclins Cln1 and Cln2 accumulate at the end of G1 at the Start transition. This is critical for the cell cycle to start at the right time. Cyclins are constitutively unstable, therefore, the control of Cln1 and Cln2 stability is a key mechanism for the proper regulation of cell cycle progression. In almost all previous studies, Cln1 and Cln2 degradation has been studied without distinguishing between them or only Cln2 has been investigated. For this reason, we decided to analyze the degradation of Cln1 and Cln2 separately in order to establish whether there are differences between these cyclins in this regulatory mechanism. First, we compared the stability of the two cyclins. Previous studies using pulse‐chase or transcriptional shut‐off experiments have reported a half‐life for Cln2 or total Cln1,2 ranging between 5 and 15 min 20, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29. In agreement with these values, we observed a half‐life of around 10 min for both Cln1 and Cln2 in the translational shut‐off assays. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the stability of endogenous Cln1 has been addressed independently of Cln2, and our results indicate that both cyclins show an identical stability.

PEST sequences have been described as determinants of the instability of proteins degraded via the SCF ubiquitin ligase 59, 60. In this work, we attempted to analyze the functionality of the PEST sequences present in Cln1 and Cln2, which proved especially relevant in the case of the PESTb of Cln1 given its low predictive value as a PEST. We conclude that Cln1 PESTb is functional and that, in fact, it seems to confer greater instability than the equivalent PEST of Cln2, as deduced from the shorter half‐life of Chimera 2 compared to Cln2. However, it cannot be ruled out that the greater instability of Chimera 2 is caused by adjacent regions to the PEST sequence, which may affect its functionality. Consistent with this, it has been described that removing or introducing PEST sequences to different cell cycle regulators affects their stability but the effects are magnified if neighboring domains are included. This is the case of the stable versions of Cln1, Cln2 and Cln3, which lose large areas covering all or part of the PEST regions 20, 61. Likewise, the transfer to a heterologous protein of the entire C‐terminal domain of Cln2 but not the transfer of just the PEST region has a quantitative important effect on protein stability 26, 31. So it is possible that regions around PESTb in the C‐terminal region of Cln1 may modulate its function. In any case, it is clear that the interchange of the C‐terminal region for that of Cln1 destabilizes the Cln2 protein. It must be note that this destabilization does not occur when a larger fragment from Cln1 is introduced (Chimera 3). This must be due to the absence of a nuclear export mechanism in Chimera 3 and to the influence of subcellular localization in the cyclin stability (see below).

Another issue addressed in this work is the analysis of the ubiquitin ligase involved in Cln1 and Cln2 degradation. It is widely accepted that both cyclins are degraded by SCFGrr1 upon the basis that Cln1 and Cln2 stability increases in grr1 20, 23, cdc53 24 and some skp1 62 mutants, and, in addition, Cln1 and Cln2 bind Grr1 in vitro 23, 30. We have shown that both Cln1 and Cln2 are, in fact, degraded by the SCFGrr1 pathway but, in addition, we conclude that the degradation of Cln2, but not of Cln1, also depends on the SCFCdc4 pathway. As regards the involvement of Cdc4 in Cln degradation, the literature offers contradictory results: some authors report that there is no stabilization of Cln2 in a cdc4 mutant strain, whereas others indicate a decrease in the Cln2 degradation rate in cdc4 cells, although considerably slighter than the effect observed in a grr1 mutant strain 23, 32, 33, 34. To support Cdc4's ability to mediate Cln2 degradation, Cdc4, which is normally located inside the nucleus, has been recently described to drive Cln2 degradation when forced to locate in the cytoplasm 23. This suggests that Cln2's susceptibility to Cdc4 must depend on the colocalization of both proteins, so the differences in the reported results may be due to differences in the localization of Cln2 in yeast cells under the experimental conditions used. Our results clearly indicate that Cln2 is stabilized in a cdc4 mutant strain and, more importantly, that this is a specific behavior of Cln2 as compared to Cln1. Hence, this establishes a new regulatory difference between these two cyclins.

The results obtained with different chimeric cyclins can help to characterize the cyclin regions responsible for the differences observed between Cln1 and Cln2 degradation. Table 1 summarizes the significant sequences of each chimera and the results obtained in terms of the degradation pattern and stability. The fusion of the C‐terminal region of Cln2 (amino acids 376–545), including the PEST sequence and the adjacent regions, to a stable version of Sic1, allows recognition by SCFGrr1, but not by SCFCdc4 31. Moreover, the exchange of this region between Cln3 and Cln2, causes that Cln3 ubiquitination, which is normally mediated by both SCFGrr1 and SCFCdc4, becomes specific of SCFGrr1 23. Therefore, Cln2 PEST does not seem to mediate the specific effect of SCFCdc4 in Cln2 degradation. In fact, when we exchanged Cln2 PEST for Cln1 PESTb (Chimeras 2 and 3), the degradation pattern remained unchanged, and both chimeras were still stabilized in the cdc4 mutant strain. Thus, the PEST sequences of the two cyclins are equivalent in terms of recognition by the SCF complex, and another region of the protein must be responsible for determining sensitivity to SCFCdc4. This region is the N‐terminal fragment of Cln2 (from 1 to 224) since is the only Cln2 sequence present in Chimera 3. This conclusion is reinforced by the results obtained with Chimera 4 and Chimera 2. They differ only in the N‐terminal region of the protein. Interestingly, Chimera 4, which contains the N‐terminal region corresponding to Cln1, shows the degradation pattern of Cln1, while Chimera 2, which contains the N‐terminal region corresponding to Cln2, shows the degradation pattern of Cln2. In conclusion, the N‐terminal region of the cyclin is responsible for the difference between Cln1 and Cln2 degradation as regards the involvement of SCFCdc4.

Table 1.

Cyclin properties

| Cyclin | PEST | N‐terminal end | Nuclear export signal | F‐box prot | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cln2 | PEST Cln2 | Cln2 | Cln2 |

Grr1 Cdc4 |

Standard |

| Cln1 |

PESTa Cln1 PESTb Cln1 |

Cln1 | – | Grr1 | Standard |

| Chimera 2 | PESTb Cln1 | Cln2 | Cln2 |

Grr1 Cdc4 |

Less stability |

| Chimera 3 |

PESTa Cln1 PESTb Cln1 |

Cln2 | – |

Grr1 Cdc4 |

Standard |

| Chimera 4 | PESTb Cln1 | Cln1 | Cln2 | Grr1 | Less stability |

How can the N‐terminal region of the protein determine the degradation pattern of Cln1 and Cln2? Different possibilities are considered. The N‐terminal region contains the cyclin box, which is responsible for binding to Cdc28. Different observations suggest that Cdc28‐dependent phosphorylation is required for Cln2 degradation: the ubiquitination of Cln2 in vitro requires phosphorylation by Cdc28 29; inhibition of proteolysis during Start accumulates hyperphosphorylated forms of Cln2 20, 24; the mutation at Cdc28 phosphorylation sites stabilizes the Cln2 protein 28 and renders Cln2 unable to bind to Grr1 or Cdc4 23. For these reasons, the association with Cdc28 could influence cyclin degradation. It might be possible that differences in the cyclin‐Cdc28 binding mediated by the cyclin box explain the different degradation pattern of Cln1 and Cln2. However, the cyclin box is highly conserved between Cln1 and Cln2 (72% of identity), which argues against this possibility.

Another hypothesis is that some element present in the N‐terminal region is crucial for the recognition and degradation of the cyclin by SCFCdc4. CPD have been described in most SCFCdc4 substrates 22. In most of these cases, the importance of phosphorylation by Cdc28 at these recognition sites has been highlighted. We cannot rule out that similar sites in the N‐terminal region of Cln2 might be responsible for its recognition by SCFCdc4; however, no consensus CPD sites exist in this region of Cln2, and Cdc28 phosphorylation sites are located in the C‐terminal region of the protein, thus ruling out this possibility.

Another possibility lies in the fact that the N‐terminal region of Cln1 and Cln2 contains the sequences that drive their nuclear import 55. Cdc4 is located mainly in the nucleus so recognition by SCFCdc4 is conditioned by the subcellular localization of the target protein. Thus, Far1, which is ubiquitylated by SCFCdc4, is stabilized when exported to the cytoplasm 17 or the differences between the Cln3 and Cln2 degradation patterns, as regards Cdc4 sensitivity, could be due to differences in their subcellular localization 23. The sensitivity of Cln2 but not of Cln1 to Cdc4 may, therefore, reflect that a significant amount of Cln2 degradation, but not of Cln1 degradation, is achieved inside the nucleus. When considering that the N‐terminal regions containing the nuclear import signals are responsible for Cdc4 sensitivity, it may be suggested that a different efficiency in nuclear import may determine the degradation pattern of cyclins Cln1 and Cln2.

The subcellular localization of the cyclin may have a greater influence on cyclin degradation aside from mediating the susceptibility to Cdc4. Chimera 4 is much more unstable than Cln1. This is apparently surprising because Chimera 4, in comparison with Cln1, lacks PESTa and only contains PESTb. Interestingly, Chimera 4 contains the Cln2 nuclear export signal, which actually mediates the nuclear export of Chimera 4, a mechanism that is absent in Cln1. Therefore, the nuclear export of the cyclin causes greater instability. Consistently with this idea, the greater instability of Chimera 2, as compared to Chimera 3, is lost when the Cln2 export signal present in Chimera 2 is eliminated in Chimera 3. More importantly, we have observed that forcing nuclear localization of Cln2 renders the protein more stable. All these observations allow us to propose that cyclins Cln1 and Cln2 are more unstable in the cytosol.

In this work, we have established a new regulatory difference between Cln1 and Cln2, traditionally considered equivalent cyclins. This reinforces the high degree of specialization between cyclins in eukaryotic cells.

Author contributions

IQ acquired the data; IQ and JCI conceived and designed the project, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Spanish Government and cofinanced by ERDF from the European Union (grants number BFU2010‐20927, BFU2013‐47503 and BFU2014‐58429‐P) and by the Generalitat Valenciana (grant number GVPROMETEO2016‐123).

References

- 1. Andrews B and Measday V (1998) The cyclin family of budding yeast: abundant use of a good idea. Trends Genet 14, 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mendenhall MD and Hodge AE (1998) Regulation of Cdc28 cyclin‐dependent protein kinase activity during the cell cycle of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62, 1191–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Breeden LL (2003) Periodic transcription: a cycle within a cycle. Curr Biol 13, R31–R38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McInerny CJ (2011) Cell cycle regulated gene expression in yeasts. Adv Genet 73, 51–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Simon I, Barnett J, Hannett N, Harbison CT, Rinaldi NJ, Volkert TL, Wyrick JJ, Zeitlinger J, Gifford DK, Jaakkola TS et al (2001) Serial regulation of transcriptional regulators in the yeast cell cycle. Cell 106, 697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bean JM, Siggia ED and Cross FR (2005) High functional overlap between MluI cell‐cycle box binding factor and Swi4/6 cell‐cycle box binding factor in the G1/S transcriptional program in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics 171, 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nasmyth K and Dirick L (1991) The role of SWI4 and SWI6 in the activity of G1 cyclins in yeast. Cell 66, 995–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ogas J, Andrews BJ and Herskowitz I (1991) Transcriptional activation of CLN1, CLN2, and a putative new G1 cyclin (HCS26) by SWI4, a positive regulator of G1‐specific transcription. Cell 66, 1015–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reed SI (2006) The ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway in cell cycle control. Results Probl Cell Differ 42, 147–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Konstantinova IM, Tsimokha AS and Mittenberg AG (2008) Role of proteasomes in cellular regulation. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 267, 59–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tyers M and Jorgensen P (2000) Proteolysis and the cell cycle: with this RING I do thee destroy. Curr Opin Genet Dev 10, 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koepp DM, Harper JW and Elledge SJ (1999) How the cyclin became a cyclin: regulated proteolysis in the cell cycle. Cell 97, 431–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hershko A and Ciechanover A (1998) The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem 67, 425–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peters J‐M (2002) The anaphase‐promoting complex: proteolysis in mitosis and beyond. Mol Cell 9, 931–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zachariae W and Nasmyth K (1999) Whose end is destruction: cell division and the anaphase‐promoting complex. Genes Dev 13, 2039–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morgan DO (1999) Regulation of the APC and the exit from mitosis. Nat Cell Biol 1, E47–E53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blondel M, Galan JM, Chi Y, Lafourcade C, Longaretti C, Deshaies RJ and Peter M (2000) Nuclear‐specific degradation of Far1 is controlled by the localization of the F‐box protein Cdc4. EMBO J 19, 6085–6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Verma R, Feldman RM and Deshaies RJ (1997) SIC1 is ubiquitinated in vitro by a pathway that requires CDC4, CDC34, and cyclin/CDK activities. Mol Biol Cell 8, 1427–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DeSalle LM and Pagano M (2001) Regulation of the G1 to S transition by the ubiquitin pathway. FEBS Lett 490, 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barral Y, Jentsch S and Mann C (1995) G1 cyclin turnover and nutrient uptake are controlled by a common pathway in yeast. Genes Dev 9, 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blondel M, Bach SP, Bamps S, Dobbelaere J, Wiget P, Longaretti CL, Barral Y, Meijer L and Peter M (2005) Degradation of Hof1 by SCF(Grr1) is important for actomyosin contraction during cytokinesis in yeast. EMBO J 24, 1440–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Willems AR, Schwab M and Tyers M (2004) A hitchhiker's guide to the cullin ubiquitin ligases: SCF and its kin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1695, 133–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Landry BD, Doyle JP, Toczyski DP and Benanti JA (2012) F‐box protein specificity for g1 cyclins is dictated by subcellular localization. PLoS Genet 8, e1002851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Willems AR, Lanker S, Patton EE, Craig KL, Nason TF, Mathias N, Kobayashi R, Wittenberg C and Tyers M (1996) Cdc53 targets phosphorylated G1 cyclins for degradation by the ubiquitin proteolytic pathway. Cell 86, 453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wittenberg C, Sugimoto K and Reed SI (1990) G1‐specific cyclins of S. cerevisiae: cell cycle periodicity, regulation by mating pheromone, and association with the p34CDC28 protein kinase. Cell 62, 225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salama SR, Hendricks KB and Thorner J (1994) G1 cyclin degradation: the PEST motif of yeast Cln2 is necessary, but not sufficient, for rapid protein turnover. Mol Cell Biol 14, 7953–7966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Richardson HE, Wittenberg C, Cross F and Reed SI (1989) An essential G1 function for cyclin‐like proteins in yeast. Cell 59, 1127–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lanker S, Valdivieso MH and Wittenberg C (1996) Rapid degradation of the G1 cyclin Cln2 induced by CDK‐dependent phosphorylation. Science 271, 1597–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deshaies RJ, Chau V and Kirschner M (1995) Ubiquitination of the G1 cyclin Cln2p by a Cdc34p‐dependent pathway. EMBO J 14, 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Skowyra D, Craig KL, Tyers M, Elledge SJ and Harper JW (1997) F‐box proteins are receptors that recruit phosphorylated substrates to the SCF ubiquitin‐ligase complex. Cell 91, 209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berset C, Griac P, Tempel R, La Rue J, Wittenberg C and Lanker S (2002) Transferable domain in the G(1) cyclin Cln2 sufficient to switch degradation of Sic1 from the E3 ubiquitin ligase SCF(Cdc4) to SCF(Grr1). Mol Cell Biol 22, 4463–4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blondel M and Mann C (1996) G2 cyclins are required for the degradation of G1 cyclins in yeast. Nature 384, 279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patton EE, Willems AR, Sa D, Kuras L, Thomas D, Craig KL and Tyers M (1998) Cdc53 is a scaffold protein for multiple Cdc34/Skp1/F‐box protein complexes that regulate cell division and methionine biosynthesis in yeast. Genes Dev 12, 692–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schneider BL, Patton EE, Lanker S, Mendenhall MD, Wittenberg C, Futcher B and Tyers M (1998) Yeast G1 cyclins are unstable in G1 phase. Nature 395, 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ang XL and Wade Harper J (2005) SCF‐mediated protein degradation and cell cycle control. Oncogene 24, 2860–2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koivomagi M, Valk E, Venta R, Iofik A, Lepiku M, Balog ER, Rubin SM, Morgan DO and Loog M (2011) Cascades of multisite phosphorylation control Sic1 destruction at the onset of S phase. Nature 480, 128–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mittag T, Marsh J, Grishaev A, Orlicky S, Lin H, Sicheri F, Tyers M and Forman‐Kay JD (2010) Structure/function implications in a dynamic complex of the intrinsically disordered Sic1 with the Cdc4 subunit of an SCF ubiquitin ligase. Structure 18, 494–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tang X, Orlicky S, Mittag T, Csizmok V, Pawson T, Forman‐Kay JD, Sicheri F and Tyers M (2012) Composite low affinity interactions dictate recognition of the cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor Sic1 by the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 3287–3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ahn SH, Tobe BT, Fitz Gerald JN, Anderson SL, Acurio A and Kron SJ (2001) Enhanced cell polarity in mutants of the budding yeast cyclin‐dependent kinase Cdc28p. Mol Biol Cell 12, 3589–3600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Amon A, Tyers M, Futcher B and Nasmyth K (1993) Mechanisms that help the yeast cell cycle clock tick: G2 cyclins transcriptionally activate G2 cyclins and repress G1 cyclins. Cell 74, 993–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Benton BK, Tinkelenberg AH, Jean D, Plump SD and Cross FR (1993) Genetic analysis of Cln/Cdc28 regulation of cell morphogenesis in budding yeast. EMBO J 12, 5267–5275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cvrckova F and Nasmyth K (1993) Yeast G1 cyclins CLN1 and CLN2 and a GAP‐like protein have a role in bud formation. EMBO J 12, 5277–5286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Haase SB, Winey M and Reed SI (2001) Multi‐step control of spindle pole body duplication by cyclin‐dependent kinase. Nat Cell Biol 3, 38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Henchoz S, Chi Y, Catarin B, Herskowitz I, Deshaies RJ and Peter M (1997) Phosphorylation‐ and ubiquitin‐dependent degradation of the cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor Far1p in budding yeast. Genes Dev 11, 3046–3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huang JN, Park I, Ellingson E, Littlepage LE and Pellman D (2001) Activity of the APC(Cdh1) form of the anaphase‐promoting complex persists until S phase and prevents the premature expression of Cdc20p. J Cell Biol 154, 85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lew DJ and Reed SI (1993) Morphogenesis in the yeast cell cycle: regulation by Cdc28 and cyclins. J Cell Biol 120, 1305–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schneider BL, Yang QH and Futcher AB (1996) Linkage of replication to start by the Cdk inhibitor Sic1. Science 272, 560–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schwob E, Böhm T, Mendenhall MD and Nasmyth K (1994) The B‐type cyclin kinase inhibitor p40SIC1 controls the G1 to S transition in S. cerevisiae . Cell 79, 233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Flick K, Chapman‐Shimshoni D, Stuart D, Guaderrama M and Wittenberg C (1998) Regulation of cell size by glucose is exerted via repression of the CLN1 promoter. Mol Cell Biol 18, 2492–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Loeb JD, Kerentseva TA, Pan T, Sepulveda‐Becerra M and Liu H (1999) Saccharomyces cerevisiae G1 cyclins are differentially involved in invasive and pseudohyphal growth independent of the filamentation mitogen‐activated protein kinase pathway. Genetics 153, 1535–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Madhani HD, Galitski T, Lander ES and Fink GR (1999) Effectors of a developmental mitogen‐activated protein kinase cascade revealed by expression signatures of signaling mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 12530–12535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Purnapatre K, Piccirillo S, Schneider BL and Honigberg SM (2002) The CLN3/SWI6/CLN2 pathway and SNF1 act sequentially to regulate meiotic initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genes Cells 7, 675–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Queralt E and Igual JC (2004) Functional distinction between Cln1p and Cln2p cyclins in the control of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitotic cycle. Genetics 168, 129–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bhaduri S and Pryciak PM (2011) Cyclin‐specific docking motifs promote phosphorylation of yeast signaling proteins by G1/S Cdk complexes. Curr Biol 21, 1615–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Quilis I and Igual JC (2012) Molecular basis of the functional distinction between Cln1 and Cln2 cyclins. Cell Cycle 11, 3117–3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Edgington NP and Futcher B (2001) Relationship between the function and the location of G1 cyclins in S. cerevisiae . J Cell Sci 114, 4599–4611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Soriano‐Carot M, Bano MC and Igual JC (2012) The yeast mitogen‐activated protein kinase Slt2 is involved in the cellular response to genotoxic stress. Cell Div 7, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hadwiger JA, Wittenberg C, Richardson HE, de Barros Lopes M and Reed SI (1989) A family of cyclin homologs that control the G1 phase in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86, 6255–6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rechsteiner M and Rogers SW (1996) PEST sequences and regulation by proteolysis. Trends Biochem Sci 21, 267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rogers S, Wells R and Rechsteiner M (1986) Amino acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: the PEST hypothesis. Science 234, 364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yaglom J, Linskens MH, Sadis S, Rubin DM, Futcher B and Finley D (1995) p34Cdc28‐mediated control of Cln3 cyclin degradation. Mol Cell Biol 15, 731–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bai C, Sen P, Hofmann K, Ma L, Goebl M, Harper JW and Elledge SJ (1996) SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F‐box. Cell 86, 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]