Abstract

Objective:

To determine if the flexibility of high-school-aged males would improve after a 6-week eccentric exercise program. In addition, the changes in hamstring flexibility that occurred after the eccentric program were compared with a 6-week program of static stretching and with a control group (no stretching).

Design and Setting:

We used a test-retest control group design in a laboratory setting. Subjects were assigned randomly to 1 of 3 groups: eccentric training, static stretching, or control.

Subjects:

A total of 69 subjects, with a mean age of 16.45 ± 0.96 years and with limited hamstring flexibility (defined as 20° loss of knee extension measured with the thigh held at 90° of hip flexion) were recruited for this study.

Measurements:

Hamstring flexibility was measured using the passive 90/90 test before and after the 6-week program.

Results:

Differences were significant for test and for the test-by-group interaction. Follow-up analysis indicated significant differences between the control group (gain = 1.67°) and both the eccentric-training (gain = 12.79°) and static-stretching (gain = 12.05°) groups. No difference was found between the eccentric and static-stretching groups.

Conclusions:

The gains achieved in range of motion of knee extension (indicating improvement in hamstring flexibility) with eccentric training were equal to those made by statically stretching the hamstring muscles.

Keywords: conditioning, injury prevention

Most medical professionals, coaches, and athletes consider aerobic conditioning, strength training, and flexibility as integral components in any conditioning program.1–3 Flexibility has been defined as the ability of a muscle to lengthen and allow one joint (or more than one joint in a series) to move through a range of motion.4 Loss of flexibility is defined as a decrease in the ability of a muscle to deform.4 Some of the proposed benefits of enhanced flexibility are reduced risk of injury,1–3 pain relief,5 and improved athletic performance.6,7

Three types of stretching have been traditionally defined in the literature in an effort to increase flexibility: ballistic stretching, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, and static stretching. Ballistic stretching is a technique involving a rhythmic, bouncing motion. The bouncing uses the momentum of the extremity to lengthen the muscle. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation involves the use of brief isometric contractions of the muscle to be stretched before statically stretching the muscle. Static stretching, considered the gold standard for measuring flexibility, is elongating a muscle to tolerance and sustaining the position for a length of time.6,8

The literature reflects some interesting differences of opinion in commonly held beliefs regarding flexibility training and the consideration of static stretching as the gold standard. Some authors1–3 have questioned the importance of using static stretching to help reduce injuries and improve athletic performance. Murphy9 made a compelling argument against the use of static stretching. Although static stretching is often used as a part of preactivity preparation, Murphy9 argued that the nature of static stretching is passive and does nothing to warm a muscle; further, although the hamstring muscle is the most frequently stretched muscle, it is also the most commonly strained.

Murphy9 suggested a better option for maintaining or increasing flexibility of a muscle is through active contractions using dynamic range of motion, thereby adding a fourth type of stretching. Dynamic range of motion is a technique that allows the muscle to elongate naturally and in its relaxed state. This elongation is achieved by having the subject concentrically contract the antagonist muscle to move the joint through the full available range in a slow, controlled manner to stretch the agonist muscle group. Murphy9 theorized that, as dynamic range of motion is performed, metabolic processes increase. These increases cause an increase in temperature that leads to decreased muscle viscosity and allows for a smoother contraction. This warmed muscle is more pliable and more accommodating to the forces placed on the muscle, leading to increased flexibility gains.

Although Murphy's arguments regarding the use of dynamic range of motion to increase or maintain flexibility were interesting, Bandy et al10 found that, when comparing dynamic range of motion with static stretching, the flexibility gains achieved with a static stretching program were greater than those achieved in a dynamic range-of-motion program. Therefore, the gold standard for increasing flexibility is still considered static stretching. However, questions exist as to the effectiveness of static stretching in improving athletic performance.

An activity that has not been addressed for achieving increased flexibility is eccentrically training the muscle through a full range of motion. Previous authors11 suggested that most injuries occur in the eccentric phase of activity. For example, the hamstring muscles are most commonly injured when working eccentrically while decelerating or landing. Although earlier groups have examined dynamic range of motion, none have investigated the use of an eccentric agonist contraction to improve flexibility. Eccentrically training a muscle through a full range of motion theoretically could reduce injury rates and improve athletic performance and flexibility. Therefore, our purpose was to determine if high school males were able to improve hamstring flexibility after a 6-week eccentric exercise program and to compare the changes in hamstring flexibility occurring after the eccentric program with a 6-week program of static stretching and no exercises.

METHODS

Subjects

Before data collection, we performed a power analysis to determine a priori the number of subjects needed to provide sufficient power to detect an interaction effect size of 0.40 for the 3 × 2 analysis of variance (ANOVA).12 Sixty-three subjects were needed to provide power of 0.80 at an alpha of .05 with an r = 60. With this information in mind, we recruited 81 subjects on a volunteer basis to participate. We recruited 81 subjects to ensure that the appropriate number of subjects would complete the study, even with some attrition. Subjects were selected from a pool of high school students at Texarkana, Arkansas High School. A parent or guardian signed each subject's informed consent form, and the minor signed an informed assent form. The University of Central Arkansas Institutional Review Board approved the study and all forms.

The volunteers met 4 requirements. First, the extremity to be tested had no history of impairment to the knee, thigh, hip, or lower back for 1 year before the study. Second, each subject exhibited tight hamstrings. Tight hamstrings were defined as a 30° knee-extension deficit with the hip at 90° degrees as described by Bandy and Irion.13 Third, subjects not already involved in an exercise program for the trunk or lower extremities agreed not to start a program for the duration of the study. Fourth, subjects who already were participating in a regular exercise program agreed not to increase the frequency or intensity of their program for the 6-week training period.

Equipment

Hamstring flexibility was measured using a double-armed goniometer of transparent plastic. The protractor of the goniometer was divided into 1° increments. The arms of the goniometer were 12 in (30.48 cm) in length. A bubble in an enclosed plastic container, typically used in a level, was affixed to the goniometer to help ensure maintenance of the hip at a 90° angle.

Establishment of Reliability

Before data collection, we performed a reliability study on the technique used to measure hamstring flexibility with the passive 90/90 test.14 Fifteen subjects from a sample of convenience with a mean age of 29.8 ± 10.35 years (7 males, 8 females) were positioned supine with the hip and knee flexed to 90°. The lateral epicondyle of the femur was palpated, and the goniometer was centered over it. The lateral malleolus of the tibia and the greater trochanter of the femur were then marked. The arms of the goniometer were aligned with the proximal and distal landmarks. One researcher held the goniometer, the readings of which were concealed from the other researcher with a piece of paper, while the second researcher passively moved the leg toward terminal knee extension (Figure 1).

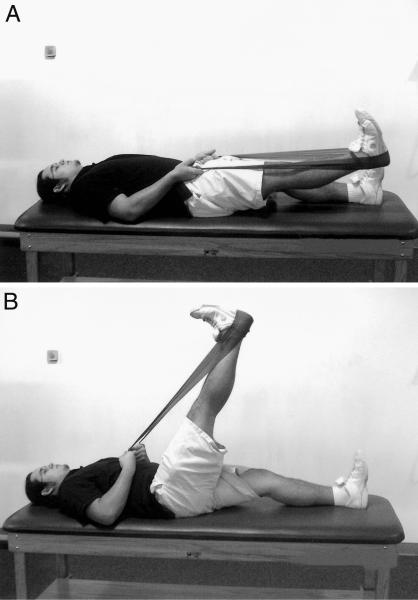

Figure 1.

The 90/90 test for measuring hamstring flexibility.

Terminal extension was determined as the point at which the researcher felt a firm resistance to the movement. Once terminal extension was reached, the researcher holding the goniometer ensured proper alignment and the blinded goniometer was revealed to the assisting examiner for the measurement to be read and recorded. Zero degrees of knee extension was considered full hamstring muscle flexibility. No warm-up was allowed before data collection. Each subject was measured twice, with 30 minutes separating measurements.

We found a mean of 20.80° ± 10.07° from full knee extension for the first measurement and 21.0° ± 10.22° for the second measurement. Using an intraclass correlation (3, 2), we calculated a reliability coefficient of .96, which was considered appropriate for proceeding with the study.

Procedures

Once reliability of the measurement was established, pretest measurement of hamstring flexibility was performed on 125 males using the same procedures and personnel described for the establishment of reliability. Of these 125 subjects, 81 males met the 4 criteria established for inclusion in the study and were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups. The control group (n = 24) performed no stretching or eccentric activities for 6 weeks.

The eccentric group (n = 24) performed full range-of-motion eccentric training for the hamstring muscles. The subject lay supine with the left leg fully extended. A 3-ft (0.91-m) piece of black Theraband (Hygenic Corp, Akron, OH) was wrapped around the heel and the subject held the ends of the Theraband in each hand. The subject was instructed to keep the right knee locked in full extension and the hip in neutral internal and external rotation throughout the entire activity (Figure 2A). The subject was then instructed to bring the right hip into full hip flexion by pulling on the Theraband attached to the foot with both arms, making sure the knee remained locked in full extension at all times. Full hip flexion was defined as the position of hip flexion at which a gentle stretch was felt by the subject (Figure 2B). As the subject pulled the hip into full flexion with the arms, he was instructed to simultaneously resist the hip flexion by eccentrically contracting the hamstring muscles during the entire range of hip flexion. The subject was instructed to provide sufficient resistance with the arms to overcome the eccentric activity of the hamstring muscles, so that the entire range of hip flexion took approximately 5 seconds to complete.

Figure 2.

A, Eccentric training, initial position. B, Final position of full hip flexion.

Once achieved, this flexed hip position was held for 5 seconds, and then the extremity was gently lowered to the ground (hip extension) by the subject's arms. This procedure was repeated 6 times, with no rest between repetitions, thereby providing a total of 30 seconds of stretching at the end range.

The static group (n = 21) statically stretched for 30 seconds 3 days per week for 6 weeks using methods described by Bandy et al1,13 and Eccles et al.11 Subjects performed the hamstring stretch by standing erect with the left foot planted on the floor and the toes pointing forward (Figure 3). The heel of the foot to be stretched was placed on a plinth/chair with the toes directed toward the ceiling. The subject then flexed forward at the hip, maintaining the spine in a neutral position while reaching the arms forward. The knee remained fully extended. The subject continued to flex at the hip until a gentle stretch was felt in the posterior thigh. Once this position was achieved, the subject maintained this position for 30 seconds.

Figure 3.

Static stretching position.

Performance of each training session by each subject was supervised and recorded by monitors. Three monitors attended a 30-minute training session in which they were instructed on the appropriate techniques for those performing eccentric training and those performing static stretching. During the first week of the training and at least every other week, the monitors were assessed to ensure that subjects were being supervised appropriately. An attendance sheet was used to document compliance with the program. If a subject missed a scheduled session, he made up the session on another day during the same week or during the next week. Any subject who missed more than 4 days of stretching was eliminated from the study.

After 6 weeks of training, all subjects were retested using the same procedures and personnel described for the pretest. Two days of rest were provided before the posttest.

Data Analysis

Means and SDs for all groups and all measurements were calculated. We used a 3 (group) × 2 (test) ANOVA with repeated measures on one variable (test) to analyze the data. Because an interaction was found, appropriate post hoc tests were performed to interpret the findings. An alpha level of P < .05 was the level of significance.

RESULTS

Sixty-nine male subjects with a mean age of 16.45 ± 0.96 years completed all requirements for this study. Twelve of the original 81 subjects were dropped for either missing too many exercise sessions or not being available for the posttest measurement. Twenty-four subjects, with a mean age of 16.29 ± 0.86 years served as the control group. The static group consisted of 21 subjects with a mean age of 16.24 ± 1.14 years. Twenty-four subjects comprised the eccentric group and had a mean age of 16.45 ± 0.96 years. The mean values for the pretest and posttest measurements of the control group for knee extension were 28.42° ± 6.00° and 27.25° ± 6.00°, respectively. The intraclass correlation coefficient (3, 2) value calculated for pretest-posttest knee-extension data of the control group was .86.

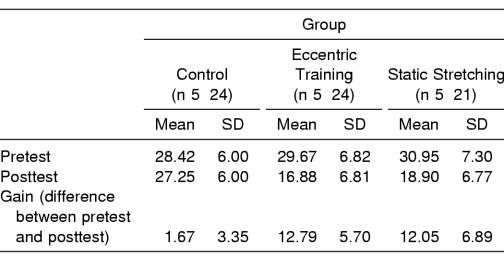

The Table presents the means for pretest and posttest measurements and gain scores for each group. We calculated significant differences for test (F1,66 = 174.60, P < .05), group (F2,66 = 3.61, P < .05), and interaction (F2,66 = 33.76, P < .05).

Pretest, Posttest, and Gain Scores for Knee Flexion (Degrees)

In order to interpret the significant group × test interaction, we performed 3 follow-up statistical analyses. First, 3 dependent t tests were calculated on the pretest to posttest change for each group. Using a Bonferroni correction to avoid inflation of the alpha level from multiple t tests, the alpha level was adjusted to P < .015. The t tests indicated significant increases in hamstring flexibility in the eccentric group (t23 = 11.00, P < .015) and the static stretching group (t20 = 8.02, P < .015) but no significant change in hamstring flexibility in the control group (t23 = 1.71, P > .015).

Second, we calculated a one-way ANOVA to assess whether any significant differences existed in the pretest scores across the groups and found none (F2,66 = .81, P > .05). Finally, a one-way ANOVA was calculated to assess the posttest scores of the 3 groups, revealing a significant difference (F2,66 = 17.64, P < .05). Tukey Honestly Significant Difference post hoc analyses indicated that the mean score of the static group (18.90° ± 6.77°) was significantly different from the control group (27.25° ± 5.89°). Also, the eccentric group (mean = 16.88° ± 6.51°) was significantly different from the control group, but the eccentric and static groups did not differ from each other.

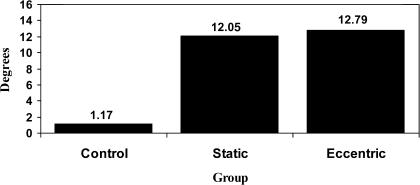

Finally, in an attempt to summarize the data, we conducted a 1-way ANOVA on gain scores, revealing a significant difference between groups (F2,66 = 33.76, P < .05). Post hoc analysis with a Tukey Honestly Significant Difference test indicated a significant difference between the gains in the static-stretching group (12.05° ± 6.89°) and the control group (1.17° ± 3.35°) and the eccentric group (12.79° ± 5.70°) and the control group. No significant difference was found between the eccentric and static-stretching groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mean change (difference between pretest and posttest) in knee extension by group.

DISCUSSION

We rejected the null hypothesis that no difference would be seen in knee-extension range of motion after 6 weeks of static stretching and eccentric training as compared with a control group (no exercise). The groups that performed static hamstring stretching and a combination of eccentric training and hip-flexion range of motion for 6 weeks showed significantly greater gains in flexibility than the control group.

Given the lack of significant difference in knee-extension range of motion between the exercise groups, eccentric training and static stretching appear to be equally effective in increasing hamstring flexibility. To date, this study is the first objective investigation of the effects of eccentric training on changes in muscle flexibility. The results support the theory that eccentric training through a full range of motion increases muscle flexibility.

The gains in knee-extension range of motion obtained in the eccentric-training group (12.79°) and static-stretching group (12.05°) are quite similar to the 3 previous longitudinal studies on the effects of duration of static stretching.1,11,13 In 2 studies, Bandy et al1,13 examined the effects of statically stretching the hamstrings for a variety of durations, including 30 seconds. The 12.50°13 and 11.50°1 gains in knee-extension range of motion after 6 weeks of statically stretching the hamstring muscle for 30 seconds were very similar to the gains by the eccentric-training and static-stretching groups in our study.

Bandy et al10 compared the effects of 30 seconds of static stretching with dynamic range of motion. Although both methods were effective in increasing range of motion, the gain made with static stretching was 11.42°, but the gain with dynamic stretching was only 4.26°.

The mechanism for the increased flexibility with eccentric hamstring activity through the full range of motion is unclear. One explanation may be found in examining the possible neurologic mechanisms that occur with stretching. Static stretching may be effective in increasing the length of muscle due to the prolonged stretching, which may allow the muscle spindle to adapt over time and cease firing.1,15 The result of this adaptation/relaxation of the muscle spindle is an increased length in the muscle. Given that eccentric exercise through the full range of motion is a continual movement lasting only 5 seconds, the muscle spindle does not appear to have time to adapt, and this explanation does not appear to be appropriate for explaining the change in flexibility due to the eccentric activity.

Although eccentric training of the hamstring muscles achieves the same flexibility gains as static stretching, the eccentric training offers a more functional option for flexibility training. Individuals training a muscle eccentrically may reduce the chance of injury by training the muscle in a more functional type of activity.16,17 Therefore, other research is now needed to determine if gains are made in strength, injury reduction, and performance improvement through an eccentric-training exercise program similar to the program used in the present study.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study was limited to the effects of eccentric training and static stretching on the flexibility of the hamstring muscles. Further studies are needed to determine if eccentric training and static stretching are equally effective in improving flexibility in other muscle groups, such as the quadriceps and triceps muscles.

Another limitation to this study is that the subjects were a sample of convenience of injury-free high school students. Therefore, our findings are most applicable to a similar age group. Although the age population in this study was limited to individuals between 15 and 17 years of age, the amount of hamstring flexibility gained in the present study was no different from other studies examining changes in static stretching in subjects between the ages of 20 and 40 years.1,10,13 Further research is needed to determine if an even older sample (eg, elderly subjects) is able to achieve similar range-of-motion gains. In addition, incorporating this exercise technique into a rehabilitation program for an injured athlete should be investigated.

CONCLUSIONS

In males ages 15 to 17 years old, hip-flexion range-of-motion gains (indicating increased hamstring flexibility) with eccentric training were equal to those made by statically stretching the hamstring muscle. Both groups (eccentric training and static stretching) increased hamstring flexibility significantly more than a control group. Over 6 weeks, the group performing the eccentric training gained 12.79°, the group performing static stretching gained 12.05°, and the control group gained 1.17°.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bandy WD, Irion JM, Briggler M. The effect of time and frequency of static stretching on flexibility of the hamstring muscles. Phys Ther. 1997;77:1090–1096. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.10.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbertsma JP, van Bolhuis AI, Goeken LN. Sport stretching: effect on passive muscle stiffness of short hamstrings. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:688–692. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartig DE, Henderson JM. Increasing hamstring flexibility decreases lower extremity overuse injuries in military basic trainees. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:173–176. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270021001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zachezewski JE. Improving flexibility. In: Scully RM, Barnes MR, editors. Physical Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1989. pp. 698–699. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henricson AS, Fredriksson K, Persson I, et al. The effect of heat and stretching on the range of hip motion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1984;6:110–115. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1984.6.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson B, Burke ER. Scientific, medical, and practical aspects of stretching. Clin Sports Med. 1991;10:63–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worrell TW, Smith TL, Winegardner J. Effect of hamstring stretching on hamstring muscle performance. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;20:154–159. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1994.20.3.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iashvilli AV. Active and passive flexibility in athletes specializing in different sports. Teorig i Praktika Fizicheskoi Kultury. 1987;7:51–52. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy DR. A critical look at static stretching: are we doing our patient harm? Chiropract Sports Med. 1991;5:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandy WD, Irion JM, Briggler M. The effect of static stretch and dynamic range of motion training on the flexibility of the hamstring muscles. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27:295–300. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.27.4.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eccles JC, Eccles R, Lindberg A. Synaptic actions on motoneurons caused by episodes of Golgi tendon organ afferents. J Physiol. 1957;138:227–252. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buasell RB, Li YF. Power Analysis for Experimental Research: A Practical Guide For The Biological, Medical and Social Sciences. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandy WB, Irion JM. The effect of time on static stretch on the flexibility of the hamstring muscles. Phys Ther. 1994;74:845–850. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.9.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reese NB, Bandy WD. Joint Range of Motion and Muscle Length Testing. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2002. pp. 354–355. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon J, Ghez C. Muscle receptors and spinal reflexes. In: Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, editors. Principles of Neural Science. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 1991. pp. 564–580. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dudley GA, Tesch PA, Miller BJ, Buchanan P. Importance of eccentric actions in performance adaptions to resistance training. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1991;62:543–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabiner MD, Owings TM, George MR, Enoka RM. Eccentric contractions are specified a priori by the CNS. Proceedings of the VXth Congress of the International Society of Biomechanics; July 2–6, 1995; Jyvaskyla, Finland. pp. 338–339. [Google Scholar]