Abstract

The p21-activated kinase 4 (PAK4) is a key downstream effector of the Rho family GTPases and is found to be over-expressed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells but not in normal human pancreatic ductal epithelia (HPDE). Gene copy number amplification studies in PDAC patient cohorts confirmed PAK4 amplification making it an attractive therapeutic target in PDAC. We investigated the anti-tumor activity of novel PAK4 allosteric modulators (PAMs) on a panel of PDAC cell lines and chemotherapy resistant flow sorted PDAC cancer stem cells (CSCs). The toxicity and efficacy of PAMs were evaluated in multiple sub-cutaneous mouse models of PDAC. PAMs (KPT-7523, KPT-7189, KPT-8752, KPT-9307 and KPT-9274) show anti-proliferative activity in vitro against different PDAC cell lines while sparing normal HPDE. Cell growth inhibition was concurrent with apoptosis induction and suppression of colony formation in PDAC. PAMs inhibited proliferation and anti-apoptotic signals downstream of PAK4. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed disruption of PAK4 complexes containing vimentin. PAMs disrupted CSC spheroid formation through suppression of PAK4. Moreover PAMs synergize with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in vitro. KPT-9274, currently in a Phase I clinical trial (clinicaltrials.gov; NCT02702492), possesses desirable PK properties and is well tolerated in mice with the absence of any signs of toxicity when 200 mg/kg daily is administered either intravenously or orally. KPT-9274 as a single agent showed remarkable anti-tumor activity in sub-cutaneous xenograft models of PDAC cell lines and CSCs. These proof-of-concept studies demonstrated the anti-proliferative effects of novel PAK4 allosteric modulators in PDAC and warrant further clinical investigations.

Keywords: Kras, PAK4, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Allosteric Modulators

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a deadly malignancy and the 4th leading cause of cancer related deaths in the United States (1). Oncogenic Ras (Kras) is the most prevalent somatic aberration (>95% mutations) in PDAC (2). Since Kras is a GTPase, the protein acts as a molecular switch recruiting and activating a repertoire of macromolecules necessary for cell proliferation, desmoplasia, maintenance of tumor heterogeneity (cancer stem-like cells or CSCs), tumor aggressiveness and metastasis (3). Even though there is a consensus regarding the importance of oncogenic Kras in PDAC, the absence of a typical druggable binding pocket in its structure has resulted in Kras remaining an elusive target for several decades (4). In order to overcome this challenge, identification of novel target sites in the Ras structure itself, in critical direct interactors or in downstream effectors are urgently needed (5).

The p21-activated kinase (PAK) family members are key effectors of the Rho family of GTPases downstream of Ras, which act as regulatory proteins controlling critical cellular processes such as cell motility, proliferation and survival (6). One of the family members, PAK4, is a key effector of Cdc42 (cell division control protein 42 homolog) and acts as a critical mediator of Ras-driven activation (7). In earlier studies, copy number alteration analysis showed amplification of PAK4 in PDAC patients (8). High resolution genomic and expression profiling in a large number of cellular and patient models have revealed putative amplifications of the PAK4 gene that has been linked to cell migration, cell adhesion, and anchorage-independent growth in PDAC (9). Therefore, PAK4 is an attractive small molecule target in the elusive Ras pathway. In addition PAK4 inhibition is proposed to overcome gemcitabine (GEM) resistance by suppressing Kras mediated proliferation of PDAC.

Earlier attempts to target PAK4 resulted in the development of an ATP competitive Type I kinase inhibitor, PF-03758309 (tested in non-pancreatic models) (10). This compound was discontinued after a single clinical trial due to undesirable PK characteristics (low human bioavailability) and lack of efficacy. Although there are several PAK4 inhibitors reported in the literature (11) none made it to the clinic. There are no studies reported that investigate the role of PAK4 as a therapy in resistant PDAC, and thus there is a void in our understanding of the impact of PAK4 inhibition in this deadly disease. Here we show that inhibition of PAK4 by novel allosteric modulators (KPT-9274 and analogs) can suppress PDAC proliferation, reverse cancer stemness, and promote synergism with chemotherapeutic agents, gemcitabine and oxaliplatin, both in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions, and research reagents

PDAC cells (MiaPaCa-2, HPAC and Panc1) were purchased from ATCC. Colo-357 and L3.6pl cells were provided by Dr. Paul J Chiao (MD Anderson Texas). HPDE cells were generously provided by Dr. Mien-Sound Tsao (Department of Pathology, Montreal General Hospital, Quebec). The cells were grown in DMEM culture medium (Invitrogen) complemented with 10% FBS (Cambrex), 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), 2 mM L glutamine (Invitrogen). Cell lines used in this study were obtained in 2009. MiaPaCa-2, HPAC and Panc1 have been authenticated yearly and recently on July 14th 2016. The method used for testing was short tandem repeat (STR) profiling using the PowerPlex® 16 System at Genetica® (Burlington, NC USA). MiaPaCa-2 CSCs were developed by flow sorting authenticated MiaPaCa-2 cells for CD44 CD133 and EpCAM. These triple positive cells were grown as spheroids in 1:1 DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with B-27 and N-2 (Invitrogen) in ultra-low attachment six well plates (Corning, USA). These cells sustained in long term culture conditions and show stem cell characteristics with mesenchymal markers (12, 13). PAMs were provided by Karyopharm Therapeutics (Newton MA, USA). Primary antibodies for PAK4, p-PAK4, GEFH1, Cyclin D1, ERK1/2, Vimentin and p65 were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). All the secondary antibodies were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Identification of PAK4 as the target PAMs utilizing Stable Isotope Labeling of Cells (SILAC)

PAMs (KPT-7523, KPT-9274, KPT-7189 and KPT-9307 or their related analogs) were obtained from Karyopharm Therapeutics (Newton Mass, USA) (14). Briefly, PAMs were immobilized on a resin through a poly-ethylene glycol (PEG) linker. MS751 cells (cervical cancer) were labeled with heavy/light arginine and lysine for at least 6 doublings. MS751 cells are sensitive to KPT-7523 in vitro (MTT at 72 hours IC50 = 30 nM). Labeled cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer and treated with DMSO or excess KPT-7523 for 2 hours. The pre-treated lysates were then incubated and rotated with KPT-7523-resin overnight at 4 °C to pull-down interacting proteins. The next day light and heavy resins were washed then mixed in equal proportions. The resin samples were boiled and the purified proteins were run on SDS-PAGE. Proteins were cut from the gel, trypsin digested then identified through Mass Spectroscopy. KPT-7523 interacting proteins were identified as those having a heavy/light ratio with >2-fold enrichment. PAK4 was identified as the strongest interactor with ~32-fold enrichment across 4 different replicates. A similar SILAC experiment in U2OS cells (MTT at 72 hours IC50 = 20 nM) confirmed these results. Follow-up biophysical assays (isothermal titration calorimetry, surface plasmon resonance and x-ray crystallography) confirmed the interaction between PAK4 and KPT-7523. Using exogenous, endogenous, and purified protein from cells, KPT-7523 showed specific interaction to PAK4 and not to PAK5 or PAK6. There was no interaction with any of the group I PAK proteins. The interaction between PAK4 and KPT-7523, however, did not impact the kinase activity of PAK4. The interaction disrupts steady state levels of PAK4 in cell lines and reduces overall PAK4 activity. Ultimately, PAK4 downstream signaling is modulated by treatment with PAK4 allosteric modulators (PAMs).

Cell growth inhibition by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (MTT)

PDAC cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well in 96-well micro-titer culture plates. After overnight incubation, medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing PAMs at indicated concentrations (0–5000 nM) diluted from a 1 mM stock. After 72 hours of incubation, MTT assay was performed by adding 20 μL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) Sigma (St. Louis, MO) solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) to each well and incubated further for 2 hours. Upon termination, the supernatant was aspirated and the MTT formazan formed by metabolically viable cells was dissolved in 100 μL of DMSO. The plates were gently rocked for 30 minutes on a gyratory shaker, and absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a plate reader (TECAN, Durham, NC).

Colonogenic Assay

50,000 cells were seeded in six well plates and allowed to grow for 24 hrs. Once attached, the cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of different PAMs (either alone or in combination with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin) for 72 hrs. At the end of the treatment period, 1,000 cells were taken from each reaction well and re-seeded in 100 mm petri dish and allowed to grow for 2 weeks at 37°C in a 5% CO2/5% O2/90% N2 incubator. Colonies were stained with 2% crystal violet, counted, and quantitated.

Sphere formation/disintegration assay

Single-cell suspensions of flow sorted MiaPaCa-2 CSC spheroids were plated on ultra–low adherent wells of 6-well plates (Corning) at 1,000 cells per well in sphere formation medium (1:1 DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with B-27 and N-2; Invitrogen). After 7 days, the spheres were collected by centrifugation (300 ×g, 5 minutes) and counted. The proportion of sphere-generating cells was calculated by dividing the number of spheres by the number of cells seeded. The sphere formation assay of secondary spheres was conducted by using primary spheres. Briefly, primary spheres were harvested and incubated with Accutase (Sigma) at 37°C for 5 to 10 minutes. Sphere disintegration assay was performed by growing 1,000 cells per well on ultra–low adherent wells of 6-well plate in the sphere formation medium and incubated with PAMs (increasing concentrations 0–1000 nM) for a total of 14 days following two days a week of drug treatment, and the cells were harvested as described previously (12). The spheres were collected by centrifugation and counted under a microscope as described above.

Quantification of apoptosis by Annexin V FITC Assay

Cell Apoptosis was detected using Annexin V FITC (Biovision Danvers MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PDAC cells were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells per well in six-well plates in 5 ml of corresponding media. 24 hrs after seeding, the cells were exposed to PAMs at different concentrations for 72 hrs. At the end of treatment period cells were trypsinized and equal numbers were stained with Annexin V and Propidum Iodide. The stained cells were analyzed using a Becton Dickinson flow cytometer at the Karmanos Cancer Institute Flow cytometry core.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were plated out at a density of 50,000 per well in regular DMEM media (with 10% FBS) in six well plates. The cells were then serum starved for 24 hr. The media was replaced with regular media containing PAMs at the indicated concentrations for 72 hrs. The cells were then harvested by trypsinization, washed once in cold PBS and resuspended in 4 ml of assay buffer (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI USA). The suspended cells were fixed by addition of 1 ml of fixative solution and incubated at 4°C overnight. Cells were then washed with PBS and incubated with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) and 100 μg/ml ribonuclease A for 30 min at 37°C according to manufacturer’s protocol (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI USA). Cells were analyzed on the Fortessa flow cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA, USA) and results were analyzed using the FlowJo Software (Ashland, OR, USA). Experiments were done in duplicate and repeated two times.

Wound healing scratch assay

PDAC cells were grown in triplicate at a density of 100,000 cells per well in six well plates. The cells were seeded in the 6-well plates in 3 ml of regular DMEM medium in each well. When the confluence of the cells grew to ~95%, the wells were then scratched with a 200-μl pipette tip followed by incubation with KPT-7523 (500 nM). The wound healing capacity was assessed and photographed with a camera-equipped inverted microscope after 72 hrs of incubation.

Western blot analysis

1×106 PDAC cells were grown in 100 mm petri-dishes over night to ~50% confluence. Next day, cells were exposed to indicated concentrations of PAMs for 72 hrs followed by extraction of protein for western blot analysis. Preparation of cellular lysates, protein concentration determination and SDS-PAGE analysis was done as described previously (15).

siRNA and transfections

To study the effect of PAK4 silencing on activity of PAMs, we utilized siRNA silencing technology. PAK4 siRNA and control siRNA were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Cells were transfected with either control siRNA or PAK4 siRNA for 24 hrs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for two cell passages according to the manufacturer’s protocol. siRNA silencing was verified using RT-PCR. All procedures have been standardized and published previously (16). The primers used for PAK4 were Forward primer: 5′-ATG TTT GGG AAG AGG AAG AAG C-3′ and Reverse primer: 5′-TCA TCT GGT GCG GTT CTG GCG-3′. After the siRNA treatment period, cells were further treated with PAMs (at IC50 concentrations) in 96-well plates for MTT and 6-well plates for Annexin V FITC assays, respectively.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

PDAC cells and MiaPaCa-2 CSCs were grown on glass chamber slides and exposed to PAMs at indicated concentrations for 72 hrs (or otherwise stated). At the end of the treatment the cells were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. The fixed slides were blocked in TBST and probed with primary and secondary antibodies according to our previously published methods (16). The slides were dried and mounting medium was added to it and covered with a coverslip and were analyzed under an inverted fluorescent microscope. A total of two independent experiments were performed.

Animal xenograft studies

All in vivo studies were conducted under Animal Investigation Committee-approved protocol. Four-week-old female ICR-SCID mice (Taconic farms) were adapted to animal housing and xenografts were developed as described earlier (15). To test the efficacy of PAM KPT-9274, bilateral fragments of the L3.6pl or AsPc-1 xenograft were implanted s.c. into naive, similarly adapted mice. Five days later, both L3.6pl and AsPc-1 cells developed into palpable tumors (~50 mg) and these tumor-bearing animals were randomly assigned to different cohorts and treated with either diluents (control group) or 140 mg/kg of KPT-9274 intravenously 5 times per week, for 4 weeks. All mice were followed for measurement of s.c. tumor weight and observed for changes in body weight and any side effects.

Statistics

Wherever appropriate, the data were subjected to a paired two-tailed Student’s t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PAK4 allosteric modulators (PAMs) suppress PDAC proliferation

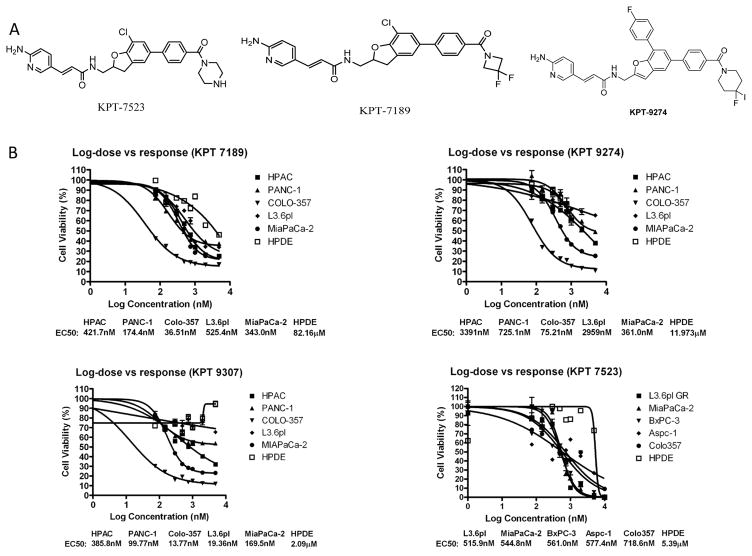

A series of novel orally bioavailable small molecules, identified by Karyopharm Therapeutics interacts with the PAK4 protein but not inhibit its kinase activity. Instead these PAK4 allosteric modulators (PAMs) effect steady state phosphorylation and total PAK4 levels in cancer cells. The interaction with PAK4 was first discovered using SILAC and a resin tagged compound, KPT-7523, as described in Materials and Methods (14, 17). Figure 1A shows the structure of PAM analogues investigated in this study. PAMs show anti-tumor activity in both solid and hematological cell lines in low nanomolar IC50 concentrations (Figure 1B and supplementary Figure 1) (14, 17). MTT assays were used to verify the anti-tumor activity of PAMs against PDAC cells in vitro. As seen in Figure 1B, most PAM analogs show potent dose dependent anti-cancer activity against a spectrum of PDAC cell lines (EC50s ~500 nM in PDAC cells) without affecting normal HPDE cells (EC50s >5 μM). These results clearly show that inhibition of PAK4 can suppress PDAC cell proliferation and can be used as a selective therapeutic strategy against oncogenic Kras-driven pancreatic tumor cells.

Figure 1. Development of PAK4 allosteric modulators with anti-PDAC activity.

[A] Structures of some of the PAMs used in this study. [B] PAMs suppress proliferation of PDAC cells (MTT assay). 5,000 PDAC or normal HPDE cells were plated per well in 96 well plates overnight. The next day the cells were exposed to increasing concentrations (0–5,000 nM) of PAMs (KPT-7189, KPT-7523, KPT-9274 and KPT-9307) for 72 hrs. Growth inhibition was evaluated using MTT assay as described in the Methods section. IC50s were calculated using Graph pad prism software. The graphs are representative of two independent experiments with six replicates for each dose tested.

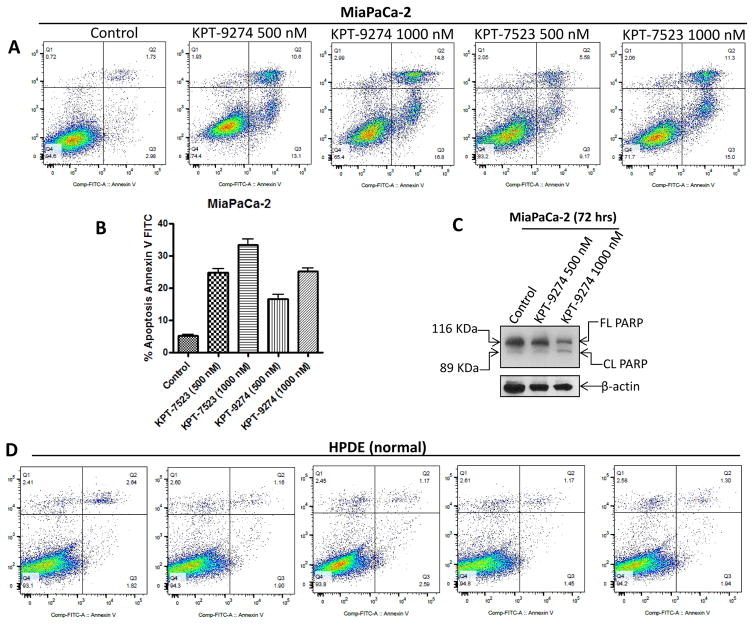

PAMs induce apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and suppress migration in PDAC cell selective manner

In order to determine whether PAMs mediated apoptosis, Annexin V FITC assay was performed. Figure 2 shows results of Annexin V FITC assay comparing PAM activity in PDAC cells (Figure 2A and B) showing significant apoptosis at 500 and 1000 nM PAM treatment for 96 hrs). PAMs were also effective in inducing apoptosis in a panel of additional PDAC cells lines (Supplementary Figure 2). Molecular analysis of KPT-9274 treated MiaPaCa-2 PDAC cells demonstrated significant PARP cleavage (Figure 2C). Most significantly, PAMs did not induce apoptosis in normal human pancreatic ductal epithelial HPDE cells (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. PAMs induce apoptosis in PDAC cell selective manner.

[A] Annexin V FITC apoptosis analysis. 50,000 MiaPaCa-2 PDAC cells were plated in six well plates in duplicate. The next day these cells were exposed to 5000 nM concentrations of PAMs for 96 hrs. At the end of the incubation period, cells were trypsinized and stained with Propidium Iodide and Annexin V FITX using Annexin V FITC assay kit (BD Biosciences) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The stained cells were immediately subject to flow cytometry analysis using Becton laminar flow at the Karmanos Cancer Institute, flow cytometry core facility. [B] Graphical representation of apoptosis analyses. [C] 1×106 MiapaCa-2 cells were grown in 100 mm petri dish and exposed to the indicated concentrations of PAM KPT-9274 for 72 hrs. Protein was isolated and subjected to western blotting as described in methods section. Blot was probed for PARP cleavage using PARP antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers MA). β-actin (Sigma St. Louis USA) was used as a loading control. [D] Annexin V FITC apoptosis analysis in normal HPDE cells under similar treatment conditions.

Earlier work from multiple independent research groups have shown that knocking down PAK4 by RNA interference suppressed the proliferation of PDAC cells (8, 18). Based on these published findings, we first explored whether PAK4 silencing has similar impact on our PDAC cell lines. Indeed, siRNA silencing of PAK4 resulted in statistically significant reduction of proliferative potential of MiaPaCa-2 and L3.6pl (Supplementary Figure 3A and B MTT assay and Supplementary Figure 3C and D showing efficient PAK4 knockdown upon siRNA treatment by RT-PCR). These observations demonstrated the critical need (oncogenic addiction) of PAK4 in subsistence of PDAC. We also investigated if PAK4 suppression by siRNA could enhance the activity of PAMs. PAM-mediated apoptosis in MiaPaCa-2 and L3.6pl is enhanced by PAK4 knockdown in these cell lines (Supplementary Figure 3E). It should be noted that siRNA only partially suppresses PAK4 protein in these cells indicating that PAMs require lesser dose to induce apoptosis (Supplementary 3 C and D).

Studies have shown that siRNA silencing of PAK4 results in the induction of cell cycle arrest in PDAC cells (18). Therefore, we investigated the impact of PAMs on different phases of cell cycle using flow cytometry analysis. When compared to control, treatment with PAMs for 72 hours resulted in consistent G2 phase arrest (~10% change) in PDAC cells (Supplementary Figure 4A and B) but not in normal HPDE cells (Supplementary Figure 4C). These results are consistent with existing siRNA work in the literature and demonstrate that PAK4 inhibition by PAMs interfere with cell cycle regulatory pathways. The Rho GTPases and their downstream effectors which include PAK proteins play an important role in cellular migration (19). Therefore, we sought to investigate the impact of PAMs on PDAC cellular migration using a standard scratch assay. When compared to vehicle control, treatment with 500 nM KPT-7523 for 48 hours resulted in substantial inhibition of scratch closure in confluent MiaPaCa-2 or L3.6pl cells (Supplementary Figure 5A and B). These results support the link between PAK proteins and cellular migration of cancer cells.

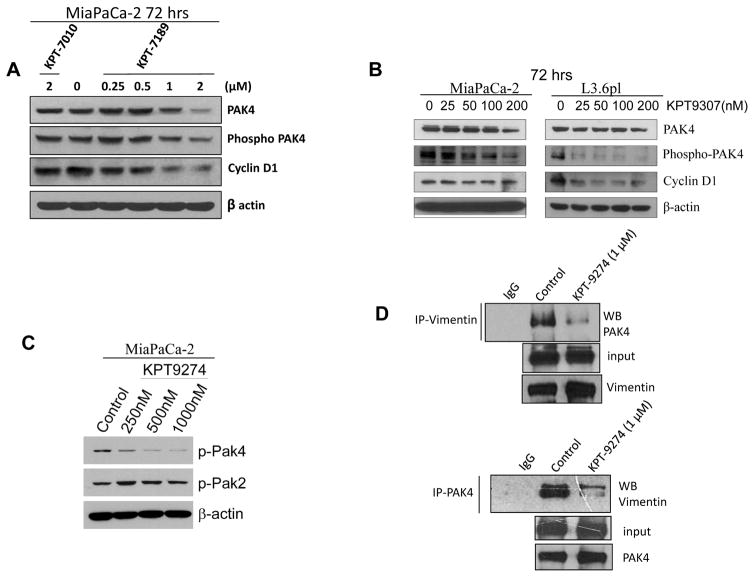

PAMs suppress PAK4 related signaling

Two recent publications have shown the specificity of PAMs towards PAK4 in distinct tumor models (14, 17). We evaluated the impact of PAMs on PAK4 and downstream signaling using western blotting. Exposure of MiaPaCa-2 cells to KPT-7189 (0–2 μM) or MiaPaCa-2 and L3.6pl cells to KPT-9307 (0–200 nM) for 72 hrs resulted in reduction of total PAK4, phosphor-S474-PAK4 (p-PAK4) and cyclin D1 (Figure 3A and B). Decrease in other major downstream signaling molecules such as ERK1/2, GEF-H1, phospho-ERK1/2 and YAP was not that drastic (data not shown). KPT-9274 and KPT-9307 reduced p-PAK4 level without effecting p-PAK2 demonstrating specificity toward PAK4 (Figure 3C). It’s important to note that the PDAC cell lines used in this study do not express all PAK isoforms. Therefore, in order exclude the role of Group I PAKs in the activity of PAMs we utilized DU-145 prostate cancer cell line that expresses PAK1, PAK2 and PAK3 as well as group II PAKs. As shown in Supplementary Figure 6, treatment of DU-145 with a sub-IC50 amount of KPT-9274 resulted in selective inhibition of p-PAK4 sparing other group I PAKs.

Figure 3. PAMs suppress PAK4 and related signaling.

[A and B] 1×106 MiaPaCa-2 and L3.6pl cells were grown in 100 mm petri dishes overnight. The next day, the cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of PAMs (either KPT-7010 (−ve control), KPT-7189, KPT-9307) for 72 hrs. At the end of the treatment period, protein was isolated using our published protocol (15). The protein lysates were subjected to western blotting using antibodies against PAK4, p-PAK4 and Cyclin D1 (Cell signaling Danvers MA). β-actin was used as a loading control (Sigma St. Louis, USA). Blots are representative of two independent experiments. [C] MiaPaCa-2 cells were exposed to KPT-9274 and protein was subjected to western blotting as described above. Blots were probed for p-PAK4 and P-PAK2 (Cell signaling, Danvers MA). β-actin was used as a loading control (Sigma St. Louis, USA). Blots are representative of two independent experiments. [D] Immunoprecipitation was performed according to established methods (15). Briefly, 200 micro gram protein lysates from control or KPT-9274 treated cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with either PAK4 or vimentin antibodies according to the manufacturers protocol using Sigma IP50 kit (Sigma St Louis). The immunoprecipitates were resolved on 10% gel and western blotting was performed. The blots were probed with anti-PAK4 or vimentin antibodies respectively (Cell Signaling, Danvers MA) with appropriate loading and internal controls. The blots are representative of two independent experiments.

Next we used a co-immunoprecipitation assay to determine whether PAMs could disrupt the interaction between PAK4 and its binding partners. In Figure 3D we demonstrated that KPT-9274 treatment resulted in the disruption of PAK4-vimentin interaction when compared to control treatment. These studies demonstrated that PAM-mediated suppression of cellular proliferation, apoptosis and cell cycle arrest were due in part to the suppression of PAK4 signaling.

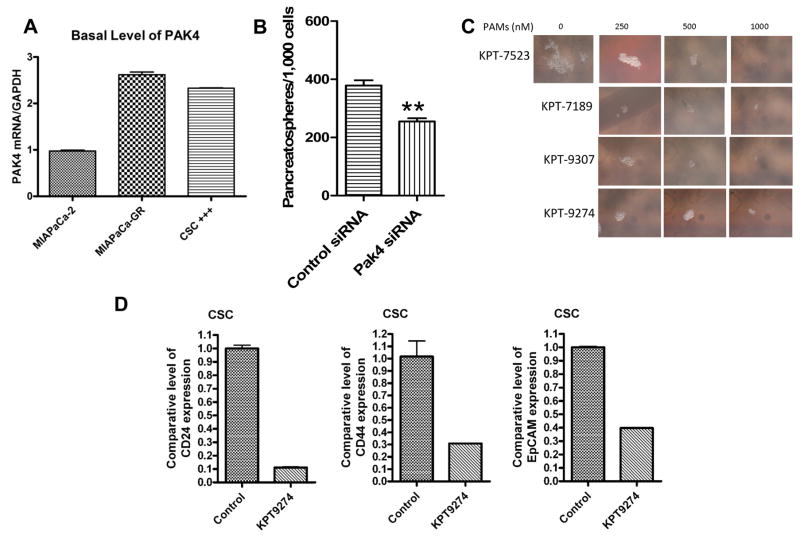

Overcoming stemness through PAK4 inhibition

In previous studies we have shown that flow sorting PDAC cells for stem like markers (CD33+CD44+EpCAM+ or CSCs) demonstrated marked resistance to standard of care chemotherapeutics such as gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (12). These flow-sorted cells harbor mesenchymal markers and have a propensity to form spheroids in long term culture conditions. Highlighting the critical role of PAK4 in the PDAC stem cell biology, we observed marked enhancement in PAK4 mRNA in gemcitabine resistant MiaPaCa-2 (MiaPaCa-2-GR) as well as MiaPaCa-2 CSCs (Figure 4A). RNAi of PAK4 in these CSCs suppressed their propensity to form spheroids in a statistically significant manner (Figure 4B). PAM treatment (twice a week for two weeks) was found to disrupt spheroids in a dose dependent manner (Figure 4C). PAMs could induce apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 7A and B) in CSCs and down-regulate EMT markers such as CD24, CD44, EpCAM (Figure 4 D) and snail (Supplementary Figure 7C). Collectively, these data show that PAMs can suppress drug resistant sub-population of PDAC CSCs with mesenchymal traits.

Figure 4. Impact of PAMs on PDAC CSCs.

[A] MiaPaCa-2 cells flow sorted for CD44+CD133+EpCAM+ according to our previously published procedure (12). Additionally, MiaPaCa-2 cells were grown for extended period of time in gemcitabine (100 nM) to develop resistance cell (MiaPaCa-2 GR). RNA isolated from CSCs or MiaPaCa-2 GR were evaluated using RT-PCR for basal expression of PAK4. [B] The sorted cells were exposed to either control siRNA or PAK siRNA according to established procedures (15). The spheroid formation in PAK4 siRNA exposed CSCs was evaluated over two weeks and the cells spheroids were counted and photographed under an inverted microscope (** p<0.01 between control and PAK4 siRNA treatment groups). [C] In a separate experiment the flow sorted CSCs were grown in ultra-low adherent six well plates and in spheroid forming media DMEM F 12 with N2 and B2 supplement (Invitrogen) and exposed to increasing concentrations of PAMs (0–1000 nM) twice a week for two weeks. The spheroids were counted under a microscope and photographed. [D] MiaPaCa-2 CSCs grown in regular media were exposed to different PAMs (5μM) for 72 hrs. At the end of the treatment period, RNA was isolated and RT-PCR was performed as described in the methods section. Note: down-regulation in stemness markers CD24, CD44 and EpCAM.

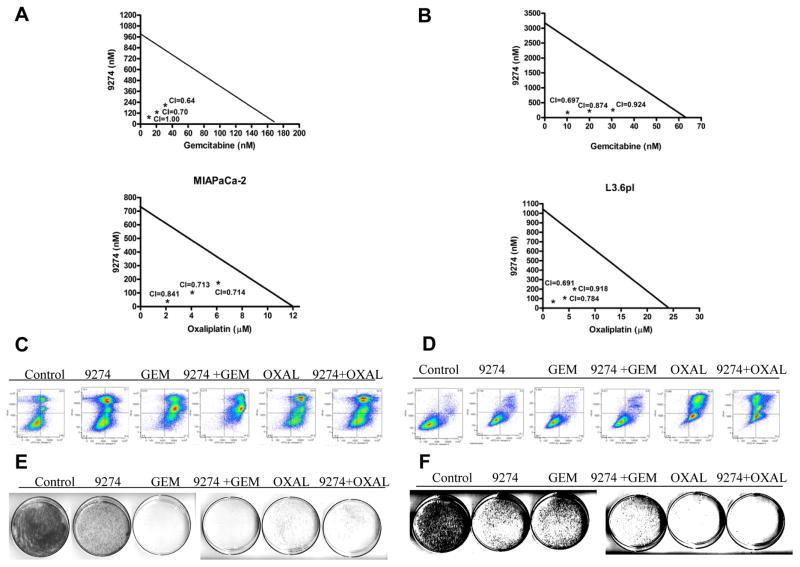

PAMs synergize with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin

Given that PAK4 is over-expressed in gemcitabine-resistant PDAC cells, we evaluated whether PAMs can synergize with two commonly used standard of care therapies in pancreatic cancer treatment; gemcitabine and oxaliplatin. KPT-9274 synergized with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in two PDAC cell lines in vitro (Figure 5A and B). Isobologram analysis showed that the combination index of KPT-9274 with either compound was synergistic (CI<1). To further demonstrate the synergy, we performed apoptosis analysis on the KPT-9274 combination treated cells. The combination of KPT-9274 with gemcitabine or oxaliplatin led to statistically significant enhancement in apoptosis when compared to either single agent alone (Figure 5C and D). Using a clonogenic assay we observed inhibition of colony formation after KPT-9274-combination treatment when compared to single agents alone in both cell lines tested (Figure 5E and F). We demonstrated synergy at the molecular level using RT-PCR analysis which demonstrated down-regulation of PAK4 mRNA in the combination treatment when compared to single agents (p < 0.01) in both PDAC cell lines (Supplementary Figure 8 A through D). Collectively the results provide strong pre-clinical rationale for the application of PAMs in combination with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin for the treatment of therapy resistant PDAC.

Figure 5. PAM-chemotherapy synergy analysis.

[A and B] MiaPaCa-2 and L3.6pl cells were seeded at a density of 5,000 cells per well in 96 well plates overnight. After 24 hrs the cells were further incubated with either KPT-9274 (60 nM, 120 nM or 180 nM), GEM (10, 20 or 40 nM), oxaliplatin (2, 4 or 8 μM) or the combination of KPT-9274 and GEM or the combination of KPT-9274 and oxaliplatin for 72 hrs. At the end of the treatment period MTT assay was performed according as described in methods section. The resulting mean of the absorbance was subject to isobologram analysis for synergy. The combination index (CI) was calculated using Calcu Syn software. Note: all the tested combinations are synergistic with CI<1. [C & D] MiaPaCa-2 and L3.6pl cells grown at a density of 50,000 cells per well in six well plates. After 24 hrs, the cells were exposed to indicated concentrations of PAM KPT-9274, GEM, oxaliplatin or their combination for 96 hrs followed by Annexin V FITC analysis as described in material and methods section. [E & F] 1000 cells from the 72 hrs single and combination treatment were plated in 100 mM petri dishes for 4 weeks. At the end of the incubation period the colonies were stained with coomassie blue and counted and photographed under the microscope.

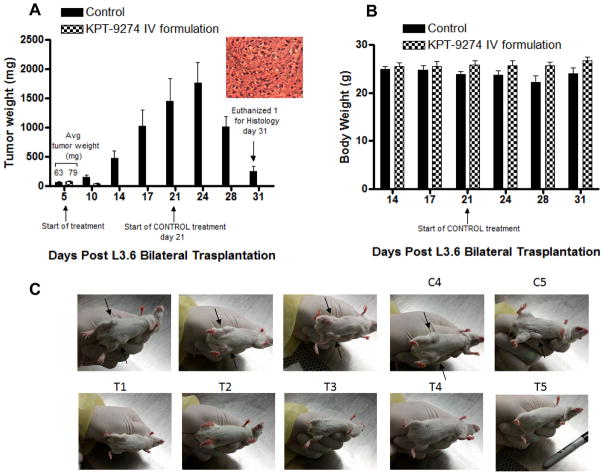

KPT-9274 shows anti-tumor activity as a single agent and in combination with gemcitabine in pre-clinical animal tumor models of PDAC

Prior to human clinical evaluation, the impact of any new anti-cancer agent needs to be validated in suitable animal tumor models. Therefore, we evaluated the anti-tumor activity of the PAM analog, KPT-9274, in xenografts of PDAC grown subcutaneously in SCID mice. As can be seen in Figure 6A, intravenous (IV) administration of KPT-9274 at 140 mg/kg for 5 days per week completely eliminated the L3.6pl PDAC tumors. We did not see any outward signs of toxicity, body weight loss (Figure 6B) or tumor rebounding (Figure 6 C showing lack of tumors in treated mice) in the treated group before termination of the experiment. In order to verify whether PAMs could regress established PDAC tumors, we exposed the control group mice (with mean tumor volume of 1500 mg) at day 21 of the experiment to KPT-9274 (140 mg/kg IV per day). To our astonishment, 3 doses of KPT-9274 treatment could regress large established tumors which did not regrow after halting drug administration. Excised tumors were examined by H & E staining and confirmed tumor cells were still present (Figure 6A inset).

Figure 6. PAM shows remarkable anti-tumor activity in animal tumor xenograft of PDAC.

[A] L3.6pl cells were grown as subcutaneous tumors in ICR-SCID mice (Taconic, USA). For the experimental groups 10 mice were trocared with ~50 mg tumors at sub-cutaneous site bilaterally. After 1 week, the mice were randomly divided into two groups control (vehicle) and treated (KPT-9274) a related PAM analog with superior pharmacokinetic properties given at 140 mg/kg i.v. once a day 5 days a week for 4 weeks. At day 21 of the experiment, KPT-9274 was administered to the control arm at a dose of 140 mg/kg i.v. once a day 5 days a week for additional week. Note: suppression of tumors in the control arm. The tumors were excised from one mouse for immunohistochemistry analysis and H&E staining confirmed the presence of tumors. [B] Mice were monitored for body weight loss and did not show any outward signs of toxicity. [C] Photographs showing control vs KPT9274 treated mice.

The L3.6pl studies were supported by another xenograft study harboring AsPC-1 tumors. In this model, treatment with KPT-9274 also demonstrated statistically significant inhibition of tumor growth (Supplementary Figure 9A; p < 0.05). We used sub-MTD oral doses of PAMs to evaluate synergy with gemcitabine. In line with the in vitro results, the combination studies with gemcitabine (given at 50 mg/kg i.v) showed marginal and statistically enhanced (p<0.05) anti-tumor activity (Supplementary Figure 9B). Collectively these findings clearly build the strong rationale for PAMs as potential therapeutics against PDAC that warrant further clinical investigations.

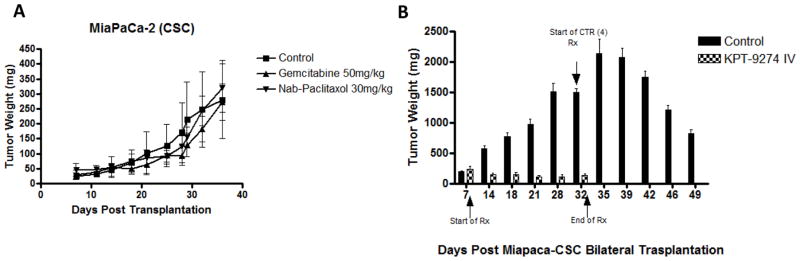

PAM suppresses highly resistant PDAC CSC derived tumors

Given that PAMs are effective against CD44+/CD133+/EpCAM+ (triple-marker-positive cells) PDAC CSCs in vitro led us to evaluate their activity against the same model in vivo. These CSCs are highly resistant to conventional chemotherapeutics since they possess stemness markers. Results of Figure 7A show that CSCs tumors do not respond to gemcitabine (given at 50 mg/kg i.p.) or nab-paclitaxel (given at 30 mg/kg i.v. once a week for two weeks). Data summarized in Figure 7B show that exposure of the chemotherapy resistant xenograft to KPT-9274 (140 mg/kg) resulted in almost complete suppression of CSC tumors. More striking were the results from the control group treated with KPT-9274 at a later time point (when tumors were reached ~1500 mg). Treatment of these large sized control tumors with KPT-9274 led to statistically significant reduction in tumor size. Marker analysis of the control residual tumor demonstrated consistent over-expression of CSC markers confirming that these tumors contained stem cells (data not show). Collectively, these multiple lines of in vitro and in vivo evidence demonstrate the potential to use KPT-9274 as an anti-tumor agent and warrants further pre-clinical and clinical evaluation for the treatment of therapy resistant PDAC.

Figure 7. PAM suppresses PDAC CSC tumors.

CD44+/CD133+/EpCAM+ (triple-marker-positive cells) were isolated as the CSLCs from human pancreatic cancer cell line MiaPaCa-2 by the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) technique and cultured in the serum-free sphere formation medium (1:1 DMEM/F-12K medium plus B27 and N2 supplements, Invitrogen) to maintain its undifferentiated status. The animal protocol was approved by the Animal Investigation Committee, Wayne State University. Female ICR-SCID severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice (4 weeks old) were purchased from Taconic Farms and fed Lab Diet 5021 (Purina Mills, Inc.). Initially, 1×106 CD44+/CD133+/EpCAM+ (triple-marker-positive cells) MiaPaCa-2 cells were implanted in xenograft mouse at the subcutaneous site bilaterally. One mouse was sacrificed after 2–3 weeks to confirm the growth of the tumor. [A] Mice harboring CSC tumors bilaterally were administered vehicle, gemcitabine or nab-paclitaxel (at indicated doses i.v. once a week for two weeks). [B] Mice harboring MiaPaCa-2 CSC and were then randomly divided into 2 groups with 6 animals in each group: (i) vehicle control; (ii) KPT-9274 140 mg/kg once daily i.v. After the termination of the treatment arm, the control group was exposed to KPT-9274 140 mg/kg i.v. at day 32 and these mice were followed till day 49. Note almost complete reduction in KPT-9274 arm and statistically significant reduction in the control arm that was exposed to KPT-9274 at late time points.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate anti-tumor activity of novel p21-activated kinase 4 (PAK4) allosteric modulators (PAMs) as single agent or in combination with chemotherapies in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), highly resistant cancer stem-like cells, and xenograft tumor models.

Despite intensive research in the last decade, there has been no significant progress in either the identification of early diagnostic markers or the development of novel therapies for this deadly disease (20). Deaths from cancers of the pancreas are projected to overtake a majority of other cancers by the year 2030 (21). While the oncogenic Kras signaling has been recognized to play a central role in the aberrant biology of >35% of all cancers it is highly significant for PDAC (>95% of tumors with Kras mutations) (22). Kras-driven cellular and animal tumor models have a positive impact on our understanding of the origins and progression of various stages of PDAC. Despite this knowledge, Kras has remained an elusive target for more than 30 years with very little progress in the development of Kras-targeted agents for use in cancer treatment, especially PDAC (23). The absence of any druggable cavity in the Kras protein structure has compounded the problem. Additional strategies to target downstream effectors of Kras have been touted as potential avenues of anti-cancer intervention. Inhibition of Kras membrane association (24), farnesyltransferases (25), Raf-MEK-ERK (26) and PI3K-AKT-mTOR (27) pathways and RalGEF-Ral (28) have all been evaluated as strategies to tame this elusive oncotarget. However, none have lived up to their potential and in most instances have failed to translate into successful clinical therapies. These failures highlight the urgent need to identify novel therapeutic strategies that can expose the impregnable oncogenic Kras fortress.

The p21-activated kinases (PAKs) are uniquely positioned at the junction of several oncogenic signaling pathways (29). There are two groups of PAKs (Group I; PAK1 - 3 and Group II; PAK4 - 6). Their importance can be illustrated by the fact that aberrant expression or mutational activation of different PAK isoforms frequently occurs in human cancers (30). A number of studies have clearly demonstrated that increased PAK activity drives multiple cellular processes feeding cancer development, sustenance and progression. The PAK family members are key effectors of the Rho family of GTPases downstream of Ras, which act as regulatory switches controlling critical cellular processes such as cell motility, proliferation and survival (6). Notably, PAK4 is a key downstream effector of Cdc42 (cell division control protein 42 homolog) (7). Gene amplification at chromosome 19q13 (i.e. PAK4) have been recorded in PDAC and has been linked to poor overall survival. PAK genes can be hyper-activated by mutations in upstream regulators such as Rac or its exchange factors. Copy number alteration analyses have shown amplification of PAK4 in cancer patients samples (8). As presented here, our analyses of the PAK4 expression patterns in regular and stem cell marker enriched flow sorted PDAC cells point to a role in supporting the stemness of CSCs.

In this study, we used a candidate group of proteins downstream of PAK4 to demonstrate anti-tumor activity of KPT-9274 and other PAMs. In agreement with our hypothesis, we observe selective inhibition of p-PAK4 with no effect on group I PAKs. Additionally, down-regulation of cyclin D1 supports the cell cycle arrest of PAMs. Further work to characterize the endogenous proteins (targeted by PAMs) regulating PAK4 is ongoing. In this direction, a recent study demonstrates that Inka1 acts as an endogenous inhibitor of PAK4(31). We are currently evaluating the impact of PAMs on Inka1 expression and its consequence on PAK4 protein expression. Additional downstream targets influenced by PAM activity were recently described by our collaborators in kidney and esophageal tumor models (14, 17). These findings are highly significant and further support the rational development of KPT-9274 for treatment of chemotherapy resistant tumors.

Most of the pharmaceutical companies developing PAK4 inhibitors have focused on Type I or ATP competitive inhibitors. Earlier attempts to target PAK4 resulted in the development of PF-03758309 which was prematurely discontinued in a single clinical trial due to lack of efficacy as well as undesirable pharmacokinetic characteristics (<1% human bioavailability; NCT00932126) (32). A major drawback of PF-03758309 was its propensity as a substrate of the multi-drug transporters contributing to its low bioavailability in humans (33). Another group developed a potent PAK4 inhibitor, LCH-7749944, which was not only effective in suppressing PAK4 activity but could also interfere with plasticity and filapodia formation in gastric cell lines (34). However, its clinical utility has yet to be explored. Non-synthetic plant derived natural agents have also been explored for their ability to inhibit PAK4 activity. Glaucarubinone isolated from the seeds of the Simarouba glauca tree was also shown to inhibit PAK4 protein expression in Kras-driven pancreatic cancer cellular and animal models (35). Glaucarubinone could also synergize with standard chemotherapeutic gemcitabine in a PAK4 dependent manner. However, it should be noted that PAK4 is not the primary target of Glaucarubinone which was originally developed as an anti-malarial agent. Being a natural agent, it most likely has pleiotropic effects complicating its development as a therapeutic agent. A recent group, using high throughput screening and structure based drug design, identified a novel PAK4 inhibitor, KY-04031 (36). Unfortunately, KY-04031 showed very low binding affinity towards PAK4 and required high micro molar concentrations to inhibit cell proliferation in PAK4 dependent manner. This agent serves only as a scaffold for future development of novel PAK4 agents. Aside from these pre-clinical agents, the field has not produced any PAK4-targeted clinical stage compounds. PAK proteins possess a very flexible ATP binding cleft in their structure rendering the design of a specific ATP competitive inhibitor very difficult. These could be some of the reasons for the lack of any objective responses with Type I kinase inhibitors in the clinic and therefore drive the urgency for the discoveries of alternative drugs.

In the absence of any clinically successful ATP competitive Type I PAK4 inhibitors, the development of allosteric or Type II modulators against PAK4 becomes a distinct and attractive approach to control this important player in the Kras pathway. However, non-ATP competitive inhibitor development is an underappreciated area of research. As presented in this paper, the PAK4 allosteric modulators could fill this void and become a much needed alternative in this stagnated field.

KPT-9274 is not a substrate of the multi-drug transporters which plagued the pharmacokinetic properties of the Pfizer compound (data not shown). This is certainly an advantage over its predecessor that has been halted from further clinical evaluation. Increased clinical utility of PAMs may be realized in the synergism with low-dose gemcitabine or oxaliplatin leading to improved anti-tumor activity with no observed toxicity in mice. Aside from pancreatic cancer models, PAK4 allosteric modulators have also shown activity is other solid and hematological malignancies in vitro (see supplementary Figure 1 for the anti-tumor activity of PAM analog across >100 different cancer cell lines).

Most interestingly, KPT-9274 and analogs are effective against pancreatic cancer stem cells that undergo EMT. These are highly significant findings as Cdc42 and Rho GTPases are known to promote motility pathways such as directional filapodia migration (37, 38). It should be noted that cellular motility (such as that observed during EMT) is catalyzed by a multitude mechanisms that includes activation through the NAD+ biosynthetic enzyme, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT/PBEF/visfatin) (39). NAMPT mediates directionally persistent migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and cancer cells (40). Closing the loop, NAMPT have been shown to activate Cdc42 (40). Being downstream of Cdc42, PAMs can be in principle dual inhibitors for both NAMPT and PAK4. The PAK4-NAMPT dual inhibitory activity of PAMs was recently described (14). Given these recent publications, we are currently evaluating the anti-NAMPT activity of PAMs in PDAC. Nevertheless, these are beyond the scope of this manuscript.

Being the direct effectors of oncogenic Kras, PAK genes are high value targets. As shown in this study, the PAK4 protein acts as a central signaling node in cancer cells and when inhibited it can have a meaningful impact on Kras pathway in pre-clinical models of PDAC. Despite several serious attempts to develop PAK4 targeted drugs, a clinically viable agent has not come to fruition. This is exemplified by the failure of the first-in-class Type I ATP competitive PAK inhibitor (PF-03758309) and highlights the unmet clinical challenge of therapeutically targeting PAK4 and other related kinases. KPT-9274 described in this study has recently entered Phase I clinical evaluation in patients with advanced solid malignancies and NHL (clinicaltrials.gov; NCT02702492), can be evaluated in PDAC patients directly and warrants further evaluation in other cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH R21 grant 1R21CA188818-01A1 to Azmi AS is acknowledged. Karyopharm Therapeutics, Inc. is acknowledged for partly funding this study. The authors thank the SKY Foundation, James H Thie foundation and Perri Foundation for supporting part of this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: William Senapedis, Erkan Baloglu, Yosef Landesman, Michael Kauffman and Sharon Shacham are employees of Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc. William Senapedis holds patent, equity and stocks and has received both major and minor renumerations from Karyopharm. All other authors have no potential conflict of interests.

Reference List

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heestand GM, Kurzrock R. Molecular landscape of pancreatic cancer: implications for current clinical trials. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4553–61. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris JP, Wang SC, Hebrok M. KRAS, Hedgehog, Wnt and the twisted developmental biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:683–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martini M, Vecchione L, Siena S, Tejpar S, Bardelli A. Targeted therapies: how personal should we go? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:87–97. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tse MT. Anticancer drugs: A new approach for blocking KRAS. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:506. doi: 10.1038/nrd4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dart AE, Wells CM. P21-activated kinase 4--not just one of the PAK. Eur J Cell Biol. 2013;92:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakoshima T, Shimizu T, Maesaki R. Structural basis of the Rho GTPase signaling. J Biochem. 2003;134:327–31. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimmelman AC, Hezel AF, Aguirre AJ, Zheng H, Paik JH, Ying H, et al. Genomic alterations link Rho family of GTPases to the highly invasive phenotype of pancreas cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19372–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809966105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahlamaki EH, Kauraniemi P, Monni O, Wolf M, Hautaniemi S, Kallioniemi A. High-resolution genomic and expression profiling reveals 105 putative amplification target genes in pancreatic cancer. Neoplasia. 2004;6:432–9. doi: 10.1593/neo.04130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray BW, Guo C, Piraino J, Westwick JK, Zhang C, Lamerdin J, et al. Small-molecule p21-activated kinase inhibitor PF-3758309 is a potent inhibitor of oncogenic signaling and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9446–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911863107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph J, Crawford JJ, Hoeflich KP, Chernoff J. p21-activated kinase inhibitors. Enzymes. 2013;34(Pt. B):157–80. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420146-0.00007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bao B, Azmi AS, Aboukameel A, Ahmad A, Bolling-Fischer A, Sethi S, et al. Pancreatic cancer stem-like cells display aggressive behavior mediated via activation of FoxQ1. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:14520–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.532887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao B, Azmi AS, Li Y, Ahmad A, Ali S, Banerjee S, et al. Targeting CSCs in tumor microenvironment: the potential role of ROS-associated miRNAs in tumor aggressiveness. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;9:22–35. doi: 10.2174/1574888x113089990053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abu AO, Chen CH, Senapedis W, Baloglu E, Argueta C, Weiss RH. Dual and specific inhibition of NAMPT and PAK4 by KPT-9274 decreases kidney cancer growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azmi AS, Aboukameel A, Bao B, Sarkar FH, Philip PA, Kauffman M, et al. Selective inhibitors of nuclear export block pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and reduce tumor growth in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:447–56. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azmi AS, Philip PA, Beck FW, Wang Z, Banerjee S, Wang S, et al. MI-219-zinc combination: a new paradigm in MDM2 inhibitor-based therapy. Oncogene. 2011;30:117–26. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang YY, Lin DC, Mayakonda A, Hazawa M, Ding LW, Chien WW, et al. Targeting super-enhancer-associated oncogenes in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gut. 2016 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyagi N, Bhardwaj A, Singh AP, McClellan S, Carter JE, Singh S. p-21 activated kinase 4 promotes proliferation and survival of pancreatic cancer cells through AKT- and ERK-dependent activation of NF-kappaB pathway. Oncotarget. 2014;5:8778–89. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2713–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimastromatteo J, Houghton JL, Lewis JS, Kelly KA. Challenges of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer J. 2015;21:188–93. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal A, Saif MW. KRAS in pancreatic cancer. JOP. 2014;15:303–5. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker NM, Der CJ. Cancer: Drug for an ‘undruggable’ protein. Nature. 2013;497:577–8. doi: 10.1038/nature12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox AD, Der CJ, Philips MR. Targeting RAS Membrane Association: Back to the Future for Anti-RAS Drug Discovery? Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1819–27. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen M, Pan P, Li Y, Li D, Yu H, Hou T. Farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase I: structures, mechanism, inhibitors and molecular modeling. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20:267–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samatar AA, Poulikakos PI. Targeting RAS-ERK signalling in cancer: promises and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:928–42. doi: 10.1038/nrd4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fruman DA, Rommel C. PI3K and cancer: lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:140–56. doi: 10.1038/nrd4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper JM, Bodemann BO, White MA. The RalGEF/Ral pathway: evaluating an intervention opportunity for Ras cancers. Enzymes. 2013;34(Pt. B):137–56. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420146-0.00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radu M, Semenova G, Kosoff R, Chernoff J. PAK signalling during the development and progression of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:13–25. doi: 10.1038/nrc3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker NM, Yee CH, Chernoff J, Der CJ. Molecular Pathways: Targeting RAC-p21-Activated Serine-Threonine Kinase Signaling in RAS-Driven Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4740–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baskaran Y, Ang KC, Anekal PV, Chan WL, Grimes JM, Manser E, et al. An in cellulo-derived structure of PAK4 in complex with its inhibitor Inka1. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8681. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray BW, Guo C, Piraino J, Westwick JK, Zhang C, Lamerdin J, et al. Small-molecule p21-activated kinase inhibitor PF-3758309 is a potent inhibitor of oncogenic signaling and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9446–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911863107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradshaw-Pierce EL, Pitts TM, Tan AC, McPhillips K, West M, Gustafson DL, et al. Tumor P-Glycoprotein Correlates with Efficacy of PF-3758309 in in vitro and in vivo Models of Colorectal Cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:22. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Wang J, Guo Q, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Peng H, et al. LCH-7749944, a novel and potent p21-activated kinase 4 inhibitor, suppresses proliferation and invasion in human gastric cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;317:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeo D, Huynh N, Beutler JA, Christophi C, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS, et al. Glaucarubinone and gemcitabine synergistically reduce pancreatic cancer growth via down-regulation of P21-activated kinases. Cancer Lett. 2014;346:264–72. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryu BJ, Kim S, Min B, Kim KY, Lee JS, Park WJ, et al. Discovery and the structural basis of a novel p21-activated kinase 4 inhibitor. Cancer Lett. 2014;349:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filippi MD, Szczur K, Harris CE, Berclaz PY. Rho GTPase Rac1 is critical for neutrophil migration into the lung. Blood. 2007;109:1257–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szczur K, Xu H, Atkinson S, Zheng Y, Filippi MD. Rho GTPase CDC42 regulates directionality and random movement via distinct MAPK pathways in neutrophils. Blood. 2006;108:4205–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soncini D, Caffa I, Zoppoli G, Cea M, Cagnetta A, Passalacqua M, et al. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition as a soluble factor independent of its enzymatic activity. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:34189–204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.594721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin H, van d V, Frontini MJ, Thibert V, O’Neil C, Watson A, et al. Intrinsic directionality of migrating vascular smooth muscle cells is regulated by NAD(+) biosynthesis. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5770–80. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.