Abstract

Health organizations in Canada have invested considerable resources in strategies to improve knowledge and uptake of advance care planning (ACP). Yet barriers persist and many Canadians do not engage in the full range of ACP behaviours, including writing an advance directive and appointing a legally authorized decision-maker. Not engaging effectively in ACP disadvantages patients, their loved ones and their healthcare providers. This article advocates for greater collaboration between health and legal professionals to better support clients in ACP and presents a framework for action to build connections between these typically siloed professions.

Abstract

Les organismes de santé au Canada ont investi des ressources considérables dans des stratégies afin d'améliorer les connaissances sur la planification préalable de soins (PPS). Malgré tout, des obstacles demeurent et beaucoup de Canadiens n'ont pas encore totalement adopté les comportements reliés à la PPS, tels qu'écrire une directive médicale anticipée et nommer une personne légalement autorisée à prendre des décisions. Le manque d'efficacité de la PPS désavantage les patients, leurs proches et les prestataires de soins de santé. Cet article recommande une meilleure collaboration entre les professionnels de la santé et les avocats afin d'offrir un meilleur service de PPS aux clients, et présente un cadre d'intervention pour bâtir des liens entre ces deux professions habituellement cloisonnées.

The Canadian population is ageing, more people are living longer with chronic conditions and, importantly, many people say they want more control over their care, especially at the end of life. The recent report of the Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation (2015) urges more work to break down siloed professions and create person-centred teams. Doing so is necessary to find new ways to deal with the persistent inadequacies in healthcare systems, including in the delivery of chronic disease care, aged care and end-of-life care.

The call for change comes in well-researched reports, like that of the Advisory Panel, and also in personal stories, like Dr. Duncan Sinclair's essay (2015) on dignified care for the frail elderly and reflections on the deaths of two high-profile Canadian doctors, Dr. Donald Low and Dr. Larry Librach (Taylor and Martin 2014). Dr. Sinclair articulates his wishes – “respect for my continued dignity and personhood; staying in my home; no pain or suffering; and not being a burden to others” – that are described with remarkable consistency as what people want to prepare for a good death (Smith 2000). Dr. Sinclair also writes of his own sense of duty to “write those expectations down and put them on record” so others can meet their obligation “to follow my advance directive.”

Health organizations in Canada have invested considerable resources in strategies to improve knowledge of advance care planning (ACP) among health professionals and patients and to encourage people to think about and communicate their wishes for future healthcare (see, for example, the work of the National Advance Care Planning Task Group: www.advancecareplanning.ca/about-advance-care-planning/advance-care-planning-national-task-group). Despite these efforts, barriers persist: members of the public misunderstand ACP; professionals report they lack the time and confidence to broach ACP conversations with clients; and systems are inadequate to ensure plans are available when needed to guide healthcare decisions (Hagen et al. 2015; Lund et al. 2015). Many Canadians still do not engage in the full range of ACP behaviours, including writing an advance directive and appointing a substitute decision-maker to ensure their values, wishes and preferences are known (Teixeira et al. 2013).

Not engaging effectively in ACP disadvantages patients, their loved ones and their healthcare providers. Patients with an advance directive experience fewer medical interventions at the end of life, are less likely to be moved from their home or community care facility to a hospital and are less likely to die in a hospital (Lum et al. 2015). Substitute decision-makers often report a significant negative emotional burden (Wendler and Rid 2011), but this burden can be eased if the decision-maker is guided by the values and preferences expressed in an advance directive. A study of Canadian hospitals found alarmingly low rates of communication between healthcare providers and terminally ill patients about whether they had advance directives and about their wishes for care during their hospital admission (Heyland et al. 2013). It was reported that “close to 70% of the physician orders concerning intensity of treatment (such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and intubation) were discordant with current patient wishes. In any other area of medicine, this would be viewed as an egregious ‘failure of communication' error” (Allison and Sudore 2013: 787).

A recent systematic review concluded that improvement in the uptake and effectiveness of ACP depends on the ability to “transform systemic processes across a range of institutional settings” (Lovell and Yates 2014: 1027). We agree and propose that one important systemic transformation is greater collaboration between health and legal professionals to better support their clients in ACP. As Dr. Sinclair and others observe, we need the “silos of our healthcare ‘system' to work together in a boundary-free way” (Sinclair 2015) but we also need to recognize that older adults and people with chronic or terminal illnesses typically have intersecting medical and legal issues, and failing to address those issues in a coordinated way undermines their quality of life and care.

Three Reasons Why Health–Legal Collaboration Is Important

First, working within their professional silos, neither doctors nor lawyers are optimally effective in helping their clients with ACP. Uncertainties about the legal validity of advance directives and the authority of substitute decision-makers are barriers to doctors having ACP conversations with patients. Fears about liability for limiting care at the end of life are a further medico-legal obstacle. Lawyers also face challenges in helping their clients with ACP. A main criticism is that lawyers are too “transactional,” helping clients prepare ACP documents, but not promoting the ongoing communication that is vital to ensuring the client's wishes are known and respected (Castillo et al. 2011). Physicians express frustration with directives that use vague phrases like “no heroic measures” and focus on the rarely encountered vegetative state, but do not provide guidance to inform the range of in-the-moment decisions needed in care at the end of life (Sudore and Fried 2010). Doctors encounter situations where decision-makers for an incompetent patient say they do not know what the patient would want (Shalowitz et al. 2006). Teams provide intensive medical interventions to sustain a patient's life only to be informed days or weeks later that a directive has been found that says the person would refuse these life-prolonging interventions.

Second, some patients are more likely to talk to a lawyer than a physician about ACP. A Saskatchewan survey found that nearly half of people who had a written care plan had sought help from a lawyer to prepare the document, while only 5% had consulted with a doctor (Goodridge et al. 2013). Similarly, patients at an Ontario family practice clinic were more likely to have discussed ACP with a lawyer than their family doctor (O'Sullivan et al. 2015). A national study of sick, elderly patients and their family members found that participants discussed their end-of-life-care wishes as often or more often with a lawyer than with a family doctor or medical specialist (Heyland et al. 2013). These findings are not surprising when one considers that people seek help from lawyers to plan for their future in various ways such as writing a will and appointing someone to manage their finances. Planning for future healthcare is a logical topic for such discussions.

Third, each Canadian province and territory has its own legislation governing ACP (see Resource Library here: http://advancecareplanning.ca/resource-library/#resource-library|category:your-province-or-territory). Doing ACP right requires an accurate understanding of the rules and policies in effect in the jurisdiction where the patient lives and receives care.

Health–Legal Collaboration to Support Advance Care Planning: A Framework for Action

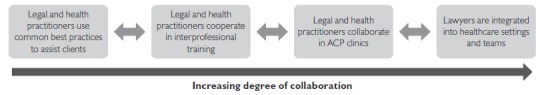

How can we break down the silos between doctors and lawyers to better support clients with ACP? We suggest a framework for interprofessional collaboration along a continuum that represents a gradually increasing degree of connection between health and legal professionals. Professionals can develop specific activities within this framework based on local needs and can move back and forth along the continuum. This framework advances the recommendation of other Canadian ACP researchers that “new forms of interprofessional collaboration should be considered to increase the interface between physicians and lawyers” (Goodridge et al. 2013: 4). We advocate that new approaches should be evaluated and findings disseminated through health and legal sector organizations to build a strong evidence base for collaborative practices.

Figure 1.

Framework for health–legal collaboration

Legal and health practitioners use common best practices to assist clients

Interventions to build professionals' skills and confidence in discussing ACP are typically implemented and evaluated in health settings; however, best practice approaches can be adapted for use by legal professionals, including resources such as conversation scripts, workbooks and training programs available on national and provincial websites (for example: www.advancecareplanning.ca/resource/acp-workbook/ and https://myhealth.alberta.ca/Alberta/Pages/advance-care-planning-resources.aspx). Organizations that produce ACP resources should disseminate them to the legal profession. Clients should receive common messages and information about ACP. For example, both health and legal professionals should promote ACP not as a one-time event but rather as a process of communication, and clients should be encouraged to share a care directive with key people who need to know their wishes.

Legal and health practitioners cooperate in interprofessional training

Continuing professional development events should bring legal and health professionals together for joint ACP training so they can learn from one another. Health professionals can increase their awareness of the law and lawyers can gain a better understanding of the practical realities of healthcare delivery. In Alberta, our research team recently delivered a continuing education event, Advance Care Planning: How Lawyers Can Help Their Clients. A palliative medicine specialist and a wills and estates lawyer shared their experiences of the challenges of doing effective ACP and suggested solutions and resources to an audience of Alberta legal professionals.

Legal and health practitioners collaborate in ACP clinics

Clinics would bring together lawyers and health professionals to lead ACP sessions for clients in community settings, aged care facilities and hospitals. This strategy can improve access to lawyers for people who are physically unable to attend law offices. Interprofessional clinics would facilitate the delivery of consistent messages and follow-up referral pathways can also be developed between legal and health organizations. Clinics can help identify clients who may need additional support, especially those with more complex situations, so they can access professional help before medical and legal crises develop.

Lawyers are integrated into healthcare settings and teams

The medical–legal partnership model (which is most developed in the US: http://medical-legalpartnership.org/) may be used to establish formal arrangements for lawyers to provide services to clients in healthcare settings. Examples exist of lawyers working with cancer and palliative care programs to help clients with legal matters, including estate and guardianship planning and benefit claims (Hallarman et al. 2014). Hallarman et al. observe that “[e]merging evidence demonstrates that patient-clients benefit substantially from the addition of legal expertise to the patient care team” (2014: 184) and, indeed, high-quality evaluation data are crucial to sustain innovative models of collaborative service delivery beyond pilot projects. The Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation heard “laments about the pervasiveness of pilot projects in Canada” and noted the “failing … in the capacity of our healthcare systems to spread or scale up the best ideas from those projects” (2015: 27). Others have reflected on factors that support the spread of successful innovations to achieve integrated systems (Suter et al. 2009), especially collective work to engage and train key groups and shift cultures of practice (Zelmer 2015).

Each increasing degree of connection in the health–legal collaboration framework presented here involves costs, benefits and a need to determine the cost-effectiveness of specific collaborative activities. Importantly, when using interprofessional approaches, members of each profession must meet their ethical duties to clients. These are not insurmountable barriers, however, as demonstrated by the success of medical–legal partnerships involving pro bono legal services (such as Pro Bono Law Ontario's Medical–Legal Partnerships for Children: www.pblo.org/volunteer/medical-legal-partnerships-children/).

ACP requires more “interdisciplinary attention, conversations, health research and practice [and] joining up professions …” (Russell 2014). Just as researchers have asked health professionals about barriers and enablers to ACP, we need to find out similar information from lawyers. Our research team will soon report on a survey of lawyers in Alberta to find out more about their experiences with ACP, their perspectives on barriers and facilitators and the resources that would help them. To our knowledge, no such survey has been done elsewhere and the results will help stakeholders in health, legal and government sectors to understand better the role that lawyers play. The results will also provide an evidence base for strategies to advance the first two components of the collaboration framework, namely, how legal and health practitioners can use common best practices to assist clients and ways in which legal and health practitioners can cooperate in interprofessional training.

Healthcare providers and lawyers need not be estranged by different professional cultures and language. To realize the benefits of ACP, they ought to find a common ground in preparing people for serious illness and death, helping people communicate what is important to them and allowing them to guide their care even beyond a time when they can speak for themselves.

Contributor Information

Nola M. Ries, Associate Professor and Deputy Dean (Research), Newcastle Law School, University of Newcastle, Australia, External Research Fellow, Health Law Institute, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Maureen Douglas, Senior Project Coordinator, Advance Care Planning CRIO Program, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Jessica Simon, Associate Professor and Division Head, Palliative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary, Physician Consultant, Advance Care Planning and Goals of Care, Calgary Zone, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, AB.

Konrad Fassbender, Assistant Professor and Scientific Director, Covenant Health Palliative Institute, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

References

- Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation. 2015. Unleashing Innovation: Excellent Healthcare for Canada. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; Retrieved March 1, 2016. <www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/publications/health-system-systeme-sante/report-healthcare-innovation-rapport-soins/alt/report-healthcare-innovation-rapport-soins-eng.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Allison T.A., Sudore R.L. 2013. “Disregard of Patients' Preferences Is a Medical Error: Comment on ‘Failure to Engage Hospitalized Elderly Patients and Their Families in Advance Care Planning'.” JAMA Internal Medicine 173(9): 787. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo L.S., Williams B.A., Hooper S.M., Sabatino C.P., Weithorn L.A., Sudore R.L. 2011. “Lost in Translation: The Unintended Consequences of Advance Directive Law on Clinical Care.” Annals of Internal Medicine 154(2): 121–28. 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge D., Quinlan E., Venne R., Hunter P., Surtees D. 2013. “Planning for Serious Illness by the General Public: A Population-Based Survey.” ISRN Family Medicine 2013: 483673. 10.5402/2013/483673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen N., Howlett J., Sharma N.C., Biondo P., Holroyd-Leduc J., Fassbender K. et al. 2015. “Advance Care Planning: Identifying System-Specific Barriers and Facilitators.” Current Oncology 22(4): e237–45. 10.3747/co.22.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallarman L., Snow D., Kapoor M., Brown C., Rodabaugh K., Lawton E. 2014. “Blueprint for Success: Translating Innovations from the Field of Palliative Medicine to the Medical-Legal Partnership.” Journal of Legal Medicine 35(1): 179–94. 10.1080/01947648.2014.885330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyland D., Barwich D., Pichora D., Dodek P., Lamontagne F., You J.J. et al. 2013. “Failure to Engage Hospitalized Elderly Patients and Their Families in Advance Care Planning.” JAMA Internal Medicine 173(9): 778–87. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell A., Yates P. 2014. “Advance Care Planning in Palliative Care: A Systematic Literature Review of the Contextual Factors Influencing Its Uptake 2008–2012.” Palliative Medicine 28(8): 1026–35. 10.1177/0269216314531313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum H.D., Sudore R.L., Bekelman D.B. 2015. “Advance Care Planning in the Elderly.” The Medical Clinics of North America 99(2): 391–403. 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund S., Richardson A., May C. 2015. “Barriers to Advance Care Planning at the End of Life: An Exploratory Systematic Review of Implementation Studies.” PLoS ONE 10(2): e0116629. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan R., Mailo K., Angeles R., Agarwal G. 2015. “Advance Directives: Survey of Primary Care Patients.” Canadian Family Physician 61(4): 353–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell S. 2014. “Advance Care Planning: Whose Agenda Is It Anyway?” Palliative Medicine 28(8): 997–99. 10.1177/0269216314543426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalowitz D.I., Garrett-Mayer E., Wendler D. 2006. “The Accuracy of Surrogate Decision Makers: A Systematic Review.” Archives of Internal Medicine 166(5): 493–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair D. 2015. “Advance Directives, Dignity and Care-Giving: A Voice for Frail Elderly Canadians.” Longwoods.com Essays. Retrieved March 1, 2016. <www.longwoods.com/content/24226>.

- Smith R. 2000. “A Good Death.” BMJ 320: 129. 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore R.L., Fried T.R. 2010. “Redefining the ‘Planning' in Advance Care Planning: Preparing for End-of-Life Decision Making.” Annals of Internal Medicine 153(4): 256–61. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter E., Oelke N.D., Adair C.E., Armitage G.D. 2009. “Ten Key Principles for Successful Health Systems Integration.” Healthcare Quarterly 13(Sp.): 16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Martin S. 2014. “Whose Death Is It Anyway? Perspectives on End-of-Life in Canada.” Healthcare Papers 14(1): 7–15. 10.12927/hcpap.2014.23963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira A.A., Hanvey L., Tayler C., Barwich D., Baxter S., Heyland D.K. 2013. “What Do Canadians Think of Advanced Care Planning? Findings from an Online Opinion Poll.” BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 5(1): 40–47.10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler D., Rid A. 2011. “Systematic Review: The Effect on Surrogates of Making Treatment Decisions for Others.” Annals of Internal Medicine 154(5): 336–36. 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelmer J. 2015. “Beyond Pilots: Scaling and Spreading Innovation in Healthcare.” Healthcare Policy 11(2): 8–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]