Abstract

The adoption of stent retrievers has significantly improved outcomes of intravenous treatment for acute stroke due to major artery occlusion, and reducing the time to recanalization may achieve further improvements. We reviewed reductions in “door-to-needle time” (DNT) and “picture-to-puncture time” (P2P), as the results of measures to consolidate stroke response capabilities in our hospital, and compared treatment outcomes in acute recanalization patients. We investigated DNT by the route of admission for 96 consecutive patients who received intravenous tissue plasminogen activator between July 2012 and June 2015. We then retrospectively studied 52 patients with acute stroke who underwent endovascular recanalization within 8 h after stroke onset, grouped according to recanalization before (Group I; n = 23) or after (Group II; n = 29) introduction of stent retrievers. Between 2012 and 2015, mean DNT decreased. Significant differences between Groups I and II were only seen in times required, with significantly shorter DNT, picture-to-puncture time, admission to puncture time, and puncture to guiding catheter placement time in Group II. A considerable difference in DNT was seen according to the route of patient admission, and consolidation of hospital stroke response capability successfully reduced the time from admission to recanalization.

Keywords: recanalization therapy, stent retriever, major artery occlusion, door-to-needle time, picture-to-puncture time

Introduction

Intravenous treatment of acute stroke due to major artery occlusion is reportedly effective, with the adoption of stent retrievers delivering a significant improvement to treatment outcomes. Some experts argue that in order to achieve even greater improvements in treatment outcomes, the time to recanalization needs to be shortened.1,2) The present study reviewed the reduction in time from hospital admission until the intravenous administration of a tissue plasminogen activator (IV-tPA), or “door-to-needle time” (DNT) and “picture-to-puncture time” (P2P), and investigated the impact of measures to consolidate the stroke response capabilities of our hospital, with the aim of minimizing the time from admission to recanalization, as well as comparing treatment outcomes in acute recanalization patients.

Materials and Methods

I. Emergency stroke treatment framework in the Tokyo metropolitan area

The type of hospital to which emergency patients in Japan are sent is determined according to the severity of the condition, which is classified into three levels.

Primary emergency: Patients with mild conditions who do not require admission to hospital.

Secondary emergency: Patients with moderate to severe conditions who require admission to hospital.

Tertiary emergency: Patients with life-threatening severe injury or serious conditions.

In the Tokyo metropolitan area, a number of hospitals have been approved as acute stroke care facilities to ensure that patients with suspected stroke are able to receive rapid and appropriate acute-phase treatment. Emergency services have adopted a system for transporting patients judged to have suffered suspected stroke to an acute stroke care facility within 24 h of onset, as stroke A patients.

Which physicians in our hospital provide the first-line emergency response varies according to the route through which the patient is brought in. Primary and secondary emergency patients are initially treated by emergency room residents in the Tokyo ER in Tama (ER route). Those designated as stroke A patients are initially dealt with by neurosurgeons (Stroke team route). Doctors at the Emergency Medical Center (EMC) take initial responsibility for tertiary emergency patients, and contact the Stroke Team if stroke is suspected (EMC route).

II. Multidisciplinary initiatives to shorten response time

Because the department in which the patients were initially treated varied according to the route by which they had been brought in, we started the following multidisciplinary initiatives to shorten response time from around July 2014.

Consolidation of emergency patient admission: We modified our response to notification of en-route stroke patients by ensuring that our ER nurses, MRI room personnel, and radiologists were notified prior to admission. We also developed an endovascular equipment set and prepared all relevant medical supplies to mitigate the workload of circulating nurses.

Preparation of recanalization therapy: We decided on an imaging strategy of plain CT followed by MRI (diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), MR angiography (MRA)). Because emergent CT angiography is not available in our hospital, and the facilities are in place to perform CT scanning and MRI without loss of time, our policy is first to rule out hemorrhage on plain CT and then to perform MRI/MRA. If the MRI findings warrant recanalization therapy, the necessary preparations for IV-tPA and recanalization therapy are undertaken simultaneously. To reduce the P2P, we have prioritized patient admission to the angiography suite, and IV-tPA is administered as soon as possible.

Integration of therapeutic procedures: From July 2014, we began developing a departmental recanalization flowsheet from admission to endovascular therapy and provided the necessary instruction so that even relatively inexperienced medical personnel could perform the necessary tests, treatments, and preparation.

Training of treatment team personnel: We continuously (approximately once a month) conduct training seminars so that our ER and emergency center nurses, ward nurses, and first-response ER residents can have up-to-date knowledge of the latest devices and evidence.

To investigate the outcome of these initiatives to reduce response time, from among patients hospitalized for acute cerebral infarction between July 2012 and June 2015, we studied 96 patients who received IV-tPA treatment and 52 who underwent endovascular recanalization during the same period. We investigated changes over time in DNT by each route of admission for patients who received IV-tPA, P2P for patients who underwent endovascular recanalization (before and after the introduction of stent retrievers in April 2014), and outcomes.

Specifically, we looked at the following variables: pre-treatment Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score – diffusion-weighted imaging (ASPECTS-DWI)3); stroke type; occluded vessel; use of combined IV-tPA; time from onset to admission; time from onset to recanalization; time from admission to imaging (MRI or CT in patients with a pacemaker); time from admission to IV-tPA; time from admission to puncture; time from admission to recanalization; time from imaging to puncture (P2P); time from imaging to recanalization; time from puncture to guiding catheter (GC) insertion; and time from GC insertion to recanalization. We also investigated the rate of effective recanalization (thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) 2b or 3)4) and the percentage of patients with a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0 to 2 after 90 days. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP®9 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test and one-way analysis of variance were used for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, and values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

I. Changes over time in DNT

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. While no differences were seen in mean age, the percentage of male patients was higher among tertiary emergency patients, at 75% (15/20), and cardiogenic embolism was the most common stroke type, seen in 14 patients (70%). Median NIHSS score on admission was 24, and endovascular treatment was significantly often performed after the administration of IV-tPA, in 12 patients (60%) among tertiary emergency patients.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics by route of admission

| ER route | Stroke team route | EMC route | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 17 | 59 | 20 | |

| Males, n (%) | 10 (58.8) | 33 (55.9) | 15 (75.0) | n.s. |

| Mean age, years (range) | 72.7 (40–88) | 76.6 (46–91) | 74.6 (47–91) | n.s. |

| Stroke type, n (%) | ||||

| Atherosclerotic | 3 (17.6) | 19 (32.2) | 6 (30.0) | n.s. |

| Cardiogenic | 12 (70.6) | 27 (45.8) | 14 (70.0) | n.s. |

| Lacunar | 1 (5.9) | 11 (18.6) | 0 | n.s. |

| Other | 1 (5.9) | 2 (3.4) | 0 | n.s. |

| NIHSS on admission (median) | 7 (1–25) | 10 (1–32) | 24 (13–38) | <0.05 |

| Endovascular recanalization, n (%) | 2 (11.8) | 21 (35.6) | 12 (60.0) | <0.05 |

EMC: emergency medical center, ER: emergency room, n.s.: not significant, NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale.

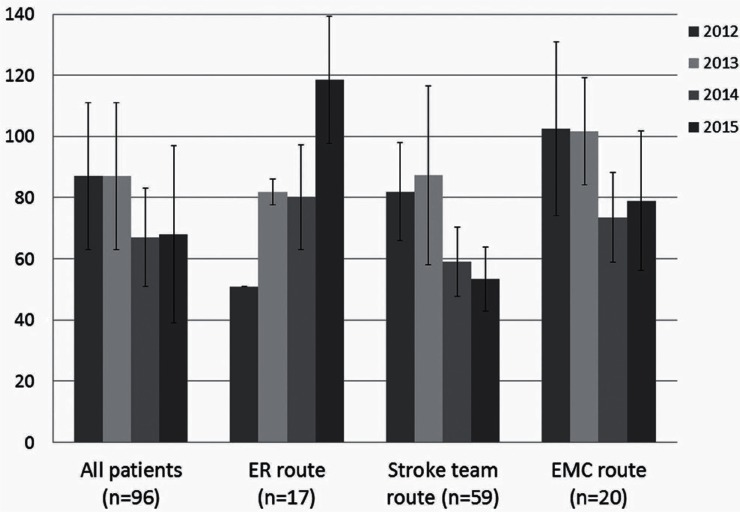

In terms of change in DNT, (Figure 1), overall mean DNT tended to decrease at 87 ± 24 min in 2012 (n = 12), 87 ± 24 min in 2013 (n = 17), 67 ± 16 min in 2014 (n = 40), and 68 ± 29 min in 2015 (n = 27). Mean time “DNT” in the 17 patients admitted to the ER actually increased between 2012 and 2015, at51 min in 2012 (n = 1), 82 ± 4 min in 2013 (n = 2), 80 ± 17 min in 2014 (n = 9), and 119 ± 20 min in 2015 (n = 5). Among Stroke team route patients (n = 59), mean DNT decreased over time from 82 ± 16 min in 2012 (n = 7) to 88 ± 29 min in 2013 (n = 12), 59 ± 11 min in 2014 (n = 22), and 53 ± 10 min in 2015 (n = 18). However, DNT among EMC route patients (n = 20) increased by more than 20 min up to 2015 compared to that of Stroke team route patients, at 103 ± 28 min in 2012 (n = 4), 102 ± 18 min in 2013 (n = 3), 74 ± 15 min in 2014 (n = 9), and 79 ± 23 min in 2015 (n = 4).

Fig. 1.

Change in door-to-needle time by route of patient admission ER: Emergency Room; EMC: Emergency Medical Center.

II. Changes over time in the temporal course of recanalization patients

We compared patients according to whether they underwent the recanalization procedure before (Group I; n = 23) or after (Group II; n = 29) adoption of the stent retriever. There were 23 Group I patients (mean age, 76.8 years) and 29 Group II patients (mean age, 77.6 years). No significant intergroup differences were seen in patient background (Tables 2 and 3). IV-tPA was administered to 13 patients in Group I (56.5%) and 15 patients in Group II (51.7%). The Merci retriever was initially used for all Group I patients, while the stent retriever was used on 21 patients in Group II (72.4%; p<0.05). Significant intergroup differences were seen in times required, with a DNT of 91 min in Group I and 62 min in Group II, P2P of 76 min in Group I and 47 min in Group II, admission to the puncture of 113 min in Group I and 85 min in Group II, and puncture to the GC placement of 57 min in Group I and 30 min in Group II. No significant differences in GC placement to recanalization were seen, at 57 min in Group I and 41 min in Group II. As a result, significant reductions were achieved in the time from puncture to recanalization (113 min in Group I versus 69 min in Group II), admission to recanalization (211 min in Group I versus 144 min in Group II), and stroke onset to recanalization (322 min in Group I versus 265 min in Group II). Conversely, no significant reductions in time were seen from stroke onset to admission or from admission to imaging. Effective recanalization was seen in 14 patients in Group I (60.9%) and 23 patients in Group II (79.3%), with TICI 3 in 4 patients in Group I (17.4%) and 12 patients in Group II (41.3%), representing a non-significant tendency toward improvement from Group I to II. In terms of complications, 11 patients showed an asymptomatic hemorrhagic infarction and none displayed symptomatic hemorrhage in Group I, while 8 had an asymptomatic hemorrhage (hemorrhagic infarction, n = 7; subarachnoid hemorrhage, n = 1) and 1 showed symptomatic hemorrhage in Group II.

Table 2.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of recanalization patients

| Group I (n = 23) | Group II (n = 29) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 10 (43.5) | 13 (44.8) | n.s. |

| Mean age (range) | 76.8 (64–89) | 77.6 (57–91) | n.s. |

| Onset type (%) | CES 20 (87.0) | CES 29 (100) | n.s. |

| Median NIHSS on admission | 14 (0–25) | 15 (1–27) | n.s. |

| ASPECTS-DWI | 6 (5–9) | 8 (5–10) | n.s. |

| IV-tPA (%) | 13 (56.5) | 15 (51.7) | n.s. |

| Occluded vessel (%) | |||

| ICA | 5 (21.7) | 6 (20.7) | n.s. |

| MCA M1 portion | 13 (56.5) | 18 (62.1) | n.s. |

| MCA M2 portion | 5 (21.7) | 5 (17.2) | n.s. |

ASPECTS-DWI: Alberta Stroke Program Early CT score - diffusion-weighted imaging, CES: cardiac embolism, ICA: internal carotid artery, IV-tPA: intravenous tissue plasminogen activator, MCA: middle cerebral artery, n.s.: not significant, NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale.

Table 3.

Methods, time course, and outcome of recanalization patients

| Group I | Group II | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | |||

| Merci retrieval system | 5 (21.7) | 0 | <0.05 |

| Penumbra reperfusion system | 18 (78.3) | 22 (75.9) | n.s. |

| Stent retriever | 0 | 21 (72.4) | <0.05 |

| Recanalization rate | |||

| TICI 0 | 3 (13.0) | 3 (10.3) | n.s. |

| TICI 1 | 0 | 0 | n.s. |

| TICI 2a | 6 (26.1) | 3 (10.3) | n.s. |

| TICI 2b | 10 (43.5) | 11 (37.9) | n.s. |

| TICI 3 | 4 (17.4) | 12 (41.4) | n.s. |

| TICI 2b/3 | 14 (60.9) | 23 (79.3) | n.s. |

| Complication (%) | |||

| Symptomatic hemorrhage | 0 | 1 | n.s. |

| Asymptomatic HI | 11 | 7 | n.s. |

| Asymptomatic SAH | 0 | 1 | n.s. |

| others | 1: puncture site occlusion | 1: perforation by microguidewire | |

| Time course minutes (mean±SD, min) | |||

| door-to-needle (tPA) | 91±36 | 62±13 | <0.05 |

| picuture-to-puncture | 76±42 | 47±16 | <0.05 |

| puncture-to-recanazliation | 113±67 | 69±29 | <0.05 |

| onset-to-recanalization | 322±90 | 265±145 | <0.05 |

| Functional outcome (%) | |||

| mRS 0–2 after 90 days | 5 (21.7) | 13 (44.8) | n.s. |

| mRS 4–6 after 90 days | 14 (60.9) | 14 (48.3) | n.s. |

HI: hemorrhagic infarction, mRS: modified Rankin Scale, n.s.: not significant SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage, SD: standard deviation, tPA: tissue-type plasminogen activator, TICI: thrombolysis in cerebral infarction.

An mRS score of 0 to 2 after 90 days was seen in five patients in Group I (21.7%) and 13 patients in Group II (44.8%), which was not significant, but was nevertheless a twofold increase. When the numbers for Groups I and II were added together, the mean onset-to-recanalization time (OTR) was 294 min (range, 148–555 min) for the 16 patients with good prognosis (mRS 0–2), and 301 min (range, 151–824 min) for the 32 patients with poor prognosis (mRS 0–3).

Discussion

These study findings indicated that consolidation of hospital stroke response capability succeeded in reducing DNT and P2P. No significant difference was seen in the intervention-based effective recanalization rates before and after adoption of the stent retriever, but the study results do show a clear increase in achieving a 90-day mRS score of 0 to 2, and that the reduction in time to treatment led to improved prognosis.

In recanalization therapy, DNT and P2P are used when setting time-based targets. The American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care recommend a target DNT of <60 min.5) In a retrospective study of 193 stroke patients who underwent endovascular treatment, Sun et al. reported that the achievement rate of an 90-day mRS score ≤2 decreased by 6% for every 10-min delay in P2P, and proposed P2P <90 min as a target for endovascular treatment.6) Meanwhile, in an analysis of data from the STAR study, Menon et al. argued that a P2P <60 min could be achieved with further improvements in the framework for medical treatment, including better preparation of imaging, IV-tPA, and endovascular therapy.7) The percentage of patients at our hospital with DNT <60 min improved from 15.4% in Group I to 53.3% in Group II, while the percentage of patients with P2P <60 min improved from 37.5% in Group I to 79.3% in Group II. We believe that time reductions can be achieved by establishing collaborative frameworks, developing protocols, and building experience into our medical teams, and that DNT and P2P <60 min are both achievable targets.

We also investigated the factors responsible for the major differences in DNT. While DNT decreased in patients who arrived via the Stroke Team and EMC routes, the time required increased year-on-year for those arriving via the ER route. The reasons may have included differences in the levels of experience of the ER residents responsible for initial treatment, as well as the fact that more time was required for initial treatment of these patients if symptoms were atypical. Patients who arrived via the EMC route may have undergone treatment for cerebral infarction that was not necessarily required, and considerable delays may thus have been seen at the time until reaching the imaging department. The study findings suggest that to achieve better treatment outcomes in patients indicated for recanalization, patients should be treated initially by the Stroke Team responsible for the treatment of stroke. Although different hospitals have different policies for determining which department is responsible for the initial treatment of stroke patients, establishing a hotline by which paramedics and other emergency services can contact the department directly responsible for stroke treatment and having them expedite the transport of suspected stroke patients would likely lead to reductions in post-admission procedural times.

These findings revealed a significant reduction in time from a puncture to recanalization, attributed mainly to decreases in preparation time as a result of greater experience and proficiency in our multidisciplinary medical team (e.g., ER and angiography suite personnel, neuroendovascular surgeons, nurses, and radiologists) and a reduction in the time from puncture to GC placement. However, the greatest contributing factor has been improved medical device performance as a result of adopting stent retrievers as a first-line therapy, allowing the standardization of techniques and streamlining of recanalization procedures. However, the potential remains for improving the skills of our medical staff, and the time from GC placement to recanalization still has room for further reduction.

The treatments described in this study were limited to those performed at our hospital, and the study population was also small. Moreover, we did not investigate recanalization rates, required times, or complications associated with each device, so detailed investigation of a larger patient population is needed to clarify methods to further reduce the time to recanalization, such as by combining surgical devices.

Conclusions

The study findings indicated a considerable difference in DNT according to the route of patient admission, while our study of recanalization patients showed that consolidation of hospital stroke response capability successfully reduced DNT and P2P. Taken together, decreases in time tended to improve the outcomes of recanalization, and continued reductions need to be sought in the future.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

The author Yuji Matsumaru received honoraria from Terumo, Covidien, Johnson and Johnson. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest. All authors who are members of The Japan Neurosurgical Society (JNS) have registered online Self-reported COI Disclosure Statement Forms through the website for JNS members.

References

- 1). Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, Nederkoorn PJ, Wermer MJ, van Walderveen MA, Staals J, Hofmeijer J, van Oostayen JA, Lycklama à Nijeholt GJ, Boiten J, Brouwer PA, Emmer BJ, de Bruijn SF, van Dijk LC, Kappelle LJ, Lo RH, van Dijk EJ, de Vries J, de Kort PL, van Rooij WJ, van den Berg JS, van Hasselt BA, Aerden LA, Dallinga RJ, Visser MC, Bot JC, Vroomen PC, Eshghi O, Schreuder TH, Heijboer RJ, Keizer K, Tielbeek AV, den Hertog HM, Gerrits DG, van den Berg-Vos RM, Karas GB, Steyerberg EW, Flach HZ, Marquering HA, Sprengers ME, Jenniskens SF, Beenen LF, van den Berg R, Koudstaal PJ, van Zwam WH, Roos YB, van der Lugt A, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Majoie CB, Dippel DW, MR CLEAN Investigators : A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 372: 11– 20, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener HC, Levy EI, Pereira VM, Albers GW, Cognard C, Cohen DJ, Hacke W, Jansen O, Jovin TG, Mattle HP, Nogueira RG, Siddiqui AH, Yavagal DR, Baxter BW, Devlin TG, Lopes DK, Reddy VK, du Mesnil de Rochemont R, Singer OC, Jahan R, SWIFT PRIME Investigators : Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med 372: 2285– 2295, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Nezu T, Koga M, Kimura K, Shiokawa Y, Nakagawara J, Furui E, Yamagami H, Okada Y, Hasegawa Y, Kario K, Okuda S, Nishiyama K, Naganuma M, Minematsu K, Toyoda K: Pretreatment ASPECTS on DWI predicts 3-month outcome following rt-PA: SAMURAI rt-PA Registry. Neurology 75: 555– 561, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Noser EA, Shaltoni HM, Hall CE, Alexandrov AV, Garami Z, Cacayorin ED, Song JK, Grotta JC, Campbell MS, 3rd: Aggressive mechanical clot disruption: a safe adjunct to thrombolytic therapy in acute stroke? Stroke 36: 292– 296, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Jauch EC, Cucchiara B, Adeoye O, Meurer W, Brice J, Chan YY, Gentile N, Hazinski MF: Part 11: adult stroke: 2010 American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 122: S818– S828, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Sun CH, Nogueira RG, Glenn BA, Connelly K, Zimmermann S, Anda K, Camp D, Frankel MR, Belagaje SR, Anderson AM, Isakov AP, Gupta R: “Picture to puncture”: a novel time metric to enhance outcomes in patients transferred for endovascular reperfusion in acute ischemic stroke. Circulation 127: 1139– 1148, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Menon BK, Almekhlafi MA, Pereira VM, Gralla J, Bonafe A, Davalos A, Chapot R, Goyal M, STAR Study Investigators : Optimal workflow and process-based performance measures for endovascular therapy in acute ischemic stroke: analysis of the Solitaire FR thrombectomy for acute revascularization study. Stroke 45: 2024– 2029, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]