Abstract

A multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach is increasingly recommended in Parkinson’s disease (PD) treatment guidelines, but no standard of care exists for such an approach, and the guidelines do not provide clarification on how it should be implemented. This paper reviews evidence of MDT interventions in people with PD and provides expert clinical perspectives for an MDT approach, with a focus on advanced PD and levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel (carbidopa–levodopa enteral suspension in the USA). The key recommendations are to enable the best possible treatment of people with PD locally by facilitating a close structured collaboration of different health care professionals working in a fixed network structure; to refer people with PD to established MDT centers in a timely manner; to establish regular meetings for the MDT enabling interdisciplinary exchange and learning; to optimize individual treatment and carefully evaluate available treatment options; to ensure treatment decisions are agreed jointly between people with PD, their caregivers, family, and health care professional; and to include specialists outside of neurology from adjuvant medical departments as necessary when implementing advanced therapies.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, multidisciplinary team, advanced therapy, levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel, carbidopa-levodopa enteral suspension

Video abstract

Introduction

A multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach has been shown to improve the quality of life (QoL)1–5 and motor function1,2,4–8 for people with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and QoL for their caregivers.9–11 Although limited studies are available, it is clear that people with PD benefit from such an approach (Table 1), and as such, it is increasingly recommended in PD treatment guidelines.12,13 Up to 20 different health care professionals may provide beneficial interventions,14 but no standard of care exists for an MDT approach, and the guidelines do not provide clarification on how it should be implemented. As a result, although the prevalence of PD increases with age to nearly 2% (1,903/100,000) in those over 80 years of age worldwide,15 many people with PD receive suboptimal management.

Table 1.

Summary of studies investigating the effect of multidisciplinary interventions in people with PD

| Article | Study title | Methodology and study population | Intervention | Outcomes assessed | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend et al4 | Short-term effectiveness of intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people with PD and their caregivers. | • Observational study (pre and post-intervention). • Patients with PD (Hoehn and Yahr Stage 1–4), with no cognitive impairment, and their caregivers. |

• Multidisciplinary rehabilitation program 1 day per week for 6 weeks for patients and caregivers, involving group activities (relaxation and talks from experts, designed to broaden patients’ knowledge of PD and its treatment) and individualized treatment. • MDT included a PDNS, consultant neurologist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, and a speech and language therapist. |

• Patients and caregivers: anxiety/depression (HADS); HRQoL (EQ-5D); social service needs; perceptions of the program. • Patients only: mobility (timed walk over 10 m); gait (number of paces in the normal timed walk over 10 m). • Assessed at baseline and after 6 weeks. |

• Improvements in patients’ mobility, gait, speech, depression, and HRQoL after the program. • Greater improvements in patients with more advanced disease at baseline. • No significant improvements in depression or QoL in caregivers. • A high unmet need for social services was identified in 31% of patients. • Patients and caregivers reported increased knowledge and understanding of PD and its treatment and high levels of satisfaction with both individual therapies and group activities. |

| Wade et al10 | Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people with PD: a randomized controlled study. | • Randomized, single-blind, controlled crossover study. • 6 weeks of active intervention vs no active intervention. • Patients with PD, without severe cognitive loss, able to travel to hospital. |

• Individualized program of one-to-one treatment over 5 weeks from a specialist team including a PDNS, a physiotherapist, a speech and language therapist, and an occupational therapist. • Each week the patient received 2 hours of individual treatment in the morning, followed by group activities (eg, talks from experts and relaxation) in the afternoon. |

• Patients: disability (PD disability questionnaire); HRQoL (PDQ-39, SF-36, EQ-5D); the stand-walk-sit test; the nine hole peg test of manual dexterity; anxiety/depression (HADS); and selected items concerning speech from the UPDRS. • Caregivers: CSI; EQ-5D • Outcomes assessed at baseline and after 24 weeks. |

• A short spell of multidisciplinary rehabilitation may improve mobility. Follow-up treatments may be needed to maintain any benefit. |

| Carne et al1 | Efficacy of a multidisciplinary treatment program on 1-year outcomes of individuals with PD. | • Retrospective cohort study evaluating the impact of active management within a coordinated, multidisciplinary PD center on disease progression of individuals with established PD. • Male veterans with PD who had been, or were being treated with levodopa or dopamine agonists at initial assessment and had a follow-up evaluation between 8 and 16 months after their initial assessment. • Patients who had undergone surgical interventions (DBS/thalamotomy) were excluded. |

• Management of PD medications; physician visits (neurologist, psychiatrist); neuropsychological evaluation; nursing visits; functional diagnostic testing (ie, gait laboratory, computerized posturography); rehabilitation therapy (physical therapy, occupational therapy, kinesiotherapy, and speech and language pathology); a home exercise program; a support group; and health and wellness education. | • Change in UPDRS Part III motor functioning score from initial assessment to 1-year follow-up examination. | • Overall mean improvement of –5.4 UPDRS Part III points over mean follow-up of 12.2 months. • 69.8% (n=30) patients showed improvement in motor functioning, 4.7% (n=2) were unchanged, and 25.6% (n=11) had worsened. |

| Carne et al2 | Efficacy of multidisciplinary treatment program on long-term outcomes of individuals with PD. | • Long-term extension of Carne et al1 (3-year follow-up). | • Management of PD medications; physician visits (neurologist, physiatrist); neuropsychological evaluation; nursing visits; functional diagnostic testing (ie, gait laboratory, computerized posturography); rehabilitation therapy (physical therapy, occupational therapy, kinesiotherapy, and speech and language pathology); a home exercise program; a support group; and health and wellness education. | • Change in UPDRS Part III motor functioning score from initial assessment to 1- to 3-year follow-up examinations. | • Improvements in UPDRS Part III scores were observed up to 3 years of follow-up. • 1-year follow-up (n=28): 78.6% (n=22) patients improved; 21.4% (n=6) worsened. • 2-year follow-up (n=15): 66.7% (n=10) patients improved; 33.3% (n=5) patients worsened. • 3-year follow-up (n=6): 83.3% (n=5) patients improved; 16.7% (n=1) worsened. |

| Ellis et al6 | Effectiveness of an inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation program for people with PD. |

• Observational study (pre and post-intervention) evaluating the effectiveness of an inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation program. • Patients with idiopathic PD, Hoehn and Yahr Stage 1–5, who were admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation hospital. |

• Multidisciplinary rehabilitation program administered for duration of hospital stay (mean stay: 20.8±7.8 days). • Program involved a combination of individualized physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy for ≥3 hours per day, 5–7 days per week. • MDT included a consultant neurologist (specializing in movement disorders), attending neurologist (specializing in neurorehabilitation), movement disorders fellow, physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech-language therapist, nurse, and case manager. |

• Primary outcome: physical and cognitive disability (FIM total score). • Secondary outcomes: motor function (FIM motor score, finger-tapping test); cognition (FIM cognition score); mobility (2-minute walk test, Timed Up and Go test). |

• Significant and clinically meaningful improvements observed across all outcomes assessed (motor function, cognition, and mobility). |

| White et al11 | Changes in walking activity and endurance following rehabilitation for people with PD. | • RCT comparing changes in walking activity and endurance following multidisciplinary rehabilitation vs no active rehabilitation. • Patients with idiopathic PD, Hoehn and Yahr Stage 2 and 3, aged ≥40 years, without significant cognitive impairment (MMSE score >26) and no substantial depression. |

• Multidisciplinary rehabilitation program lasting 6 weeks. • Patients received: 0, 3, or 4.5 hours rehabilitation per week. • MDT included a physical therapist, occupational therapist, and speech therapist, with expertise in self-management for people with PD. • Rehabilitation sessions were group-based, with the exception of the extra 1.5 hours received by the 4.5 hours/week group. These patients received individualized rehabilitation at home from a physical or occupational therapist. |

• Outcomes were assessed at baseline and after 6 weeks. • Walking activity was estimated using an activity monitor to record time spent walking and number of walking periods lasting at least 10 seconds, over a 24-hour period. • Walking endurance was measured using the 2-minute walk test. |

• Overall, no significant change in walking activity, and endurance was observed following multidisciplinary rehabilitation. • Higher doses of rehabilitation resulted in improvement in walking endurance for patients with low baseline walking endurance levels and improvement in walking activity for patients with high baseline walking activity levels. |

| Guo et al3 | Group education with personal rehabilitation for idiopathic PD. | • Single-blind RCT, with pretest/posttest quasi-experimental design, assessing the effects on patients with early-to-moderate idiopathic PD, Hoehn and Yahr Stage 1–3, without significant cognitive impairment. | • Patients randomized to intervention received three group lectures covering nutrition (by a dietitian), mood (by a psychologist), and movement. • Patients also attended a personalized rehabilitation program (24 × 30-minute sessions over 8 weeks) conducted by a physical and occupational therapist. |

• Outcomes assessed at baseline, and after 4 and 8 weeks of intervention. • Outcomes: HRQoL (PDQ-39); motor function (UPDRS Part III); activities of daily living (UPDRS Part II and SEADL); depression (SDS); patient mood (PMS); caregiver’s mood status. |

• After 8 weeks of intervention: 37% improvement in PDQ-39 scores; UPDRS Part II and III scores improved; significant improvement in patients’ and caregivers’ moods reported. |

| Tickle-Degnen et al7 | Self-management rehabilitation and health-related QoL in PD: a randomized controlled trial. | • RCT to assess the benefits of a self-management rehabilitation program on HRQoL. • Patients with idiopathic PD, Hoehn and Yahr Stage 2 and 3, without cognitive impairment (MMSE >26), aged >40 years. • Participants had not received surgical interventions (eg, DBS) for PD. |

• Patients randomized to one of three 6-week interventions: 0, 18, or 27 hours of rehabilitation. • Intervention delivered by MDT including a physical therapist, occupational therapist, and a speech therapist. |

• Outcomes assessed at baseline, after 6 weeks of intervention, and at 2 and 6 months of follow-up. • Outcomes: HRQoL (PDQ-39). |

• Beneficial effect of multidisciplinary intervention observed immediately post-intervention and at 2 and 6 months of follow-up. • Post-intervention: 54% of patients in rehabilitation groups showed significant improvement in HRQoL vs 18% of patients in control group. • 2 months of follow-up: 34% of patients in rehabilitation groups showed significant improvement in HRQoL vs 20% of patients in control group. • 6 months of follow-up: 38% of patients in rehabilitation groups showed significant improvement in HRQoL vs 10% of patients in control group. |

| van der Marck et al5 | Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for PD: a randomized, controlled trial. | • Single-blind RCT to compare outcomes for PD management following multidisciplinary care vs stand alone care from a neurologist. • Patients with PD, without dementia. |

• Intervention group received multidisciplinary care from a movement disorders specialist, PD nurse, and social worker for 8 months. • Control group received care delivered by a general neurologist for 8 months. |

• Outcomes assessed at baseline, 4 and 8 months. • Primary outcome: HRQoL (PDQ-39 score). • Secondary outcome: motor function (UPDRS Part III score). • Tertiary outcomes: UPDRS total score; depression (MADRS); psychosocial functioning (SCOPA-PS); caregiver: CSI. |

• Compared to the control group, the intervention group improved significantly at 8 months on PDQ-39 score, UPDRS Part III score, UPDRS total score, SCOPA-PS score, and MADRS score. • No difference in caregiver strain was observed between groups. |

| van der Marck et al8 | Integrated multidisciplinary care in PD: a non-randomized, controlled trial | • Non-RCT to compare an integrated multidisciplinary approach for the management of PD vs usual care. • Patients with PD, aged 20–80 years, Hoehn and Yahr Stage 1–4, without significant cognitive impairment. • Patients receiving DBS were excluded. |

• Patients in intervention region offered an individually tailored comprehensive assessment in an expert tertiary referral center. • MDT members met face-to-face to agree a treatment plan to be discussed with the patient and caregiver. • Patient subsequently referred to a regional network of allied health professionals (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and speech and language therapists). • Patients in control regions also received some multidisciplinary care, but at a lower rate than in the intervention region. |

• Primary outcomes assessed at 4, 6, and 8 months: activities of daily living (ALDS); HRQoL (PDQL). • Secondary outcomes: motor function (UPDRS Part III) at 4 months; caregiver burden at 4 and 8 months; and costs. • Tertiary outcomes: HRQoL (SF-36v2); anxiety/depression (HADS); falls efficacy scale-international; freezing of gait questionnaire; disability (SPDDS); overall well-being 100-point visual analog scale; nonmotor symptoms scale; disease severity (UPDRS Part IV); patient-specific index for physiotherapy in PD; balance; turning; Parkinson’s activity scale; fall frequency; quality of care questionnaire. • Caregivers: anxiety/depression (HADS); HRQoL (SF-36v2); view of patients’ ALDS. |

• ALDS and PDQL showed small improvements in favor of the intervention, but correction for baseline disease severity removed these differences. • UPDRS Part III and caregiver burden did not differ between control and intervention groups. • Significant improvements in HADS, SPDDS, NMSS score, SF-36, perceived general health and quality of care scores observed in intervention group vs control group. • There was no significant difference in mean costs per patient between groups. |

| Monticone et al58 | In patient multidisciplinary rehabilitation for PD: a randomized controlled trial | • Parallel group, single-blinded RCT to compare multidisciplinary rehabilitative care vs general physiotherapy. • Patients had idiopathic PD, were aged >50 years, Hoehn and Yahr Stage 2.5–4, with a decline in function, without dementia, other neurological/psychological disorders, or surgical interventions for PD. |

• Experimental group received multidisciplinary rehabilitative care including motor training (task, transfers, balance, and gait), cognitive training (attention/memory, psychomotor, executive function, visuospatial, and calculation), and ergonomic education (facilitation of new ADLs). • Control group received neuromotor techniques, mobilization, strengthening, stretching, resistance, and velocity training. |

• Primary outcome measures were assessed before treatment and 8 and 12 months following treatment: motor impairment (MDS-UPDRS Part III), balance (Italian BBS), ADL by the Italian FIM, QoL by the PDQ-39. | • After training, there was a significant between-group difference in MDS-UPDRS Part III, BBS scores, FIM, and QoL in favor of the experimental group. |

| Frazzitta et al56 | Multidisciplinary intensive rehabilitation treatment improves sleep quality in PD | • Retrospective study of a database of people with PD. • All patients had a diagnosis of clinically probable idiopathic PD, Hoehn–Yahr Stage 2 or 3, and subjective complaints of sleep disturbances. • They did not have any other neurological conditions, and had scores <8 on the Hamilton Depression scale. |

• Group 1 received multidisciplinary intensive rehabilitation treatment consisting of a 4-week physical therapy with three daily sessions, 5 days a week. Session 1 included cardiovascular activities and muscle stretches, Session 2 included activities to improve balance and gait, and Session 3 was designed to assist with ADL. • Group 2 received pharmacological therapy only. |

• UPDRS III and II scores at enrollment and Day 28. • Sleep complaints were assessed using the Italian version of the PDSS. |

• After 28 days, the baseline UPDRS scores significantly decreased in Group 1 (UPDRS III, P<0.0001; UPDRS II, P<0.0001), whereas they did not change in Group 2. • Significant improvements were observed in total PDSS scores in Group 1 (P<0.0001), particularly sleep quality, motor symptoms, and daytime somnolence. Group 2 did not show any improvement in PDSS scores. |

| Giardini et al57 | Toward proactive active living: patients with PD experience a multidisciplinary intensive rehabilitation treatment | • Qualitative study of audio recordings from semi-structured interviews with people with PD, undergoing multidisciplinary rehabilitation. • Patients had diagnosis of idiopathic PD, Hoehn and Yahr Stage 3, without cognitive impairment, psychotic symptoms or DBS. |

• A multidisciplinary intensive rehabilitation treatment consisting of 4 weeks of physical therapy with three daily sessions, 5 days a week. Session 1 included muscle stretches and exercises, Session 2 included aerobic exercises, and Session 3 was with an occupational therapist with activated to promote autonomy. • The semi-structured interview was performed during inpatients’ 4-week rehabilitation program, a few days before discharge. Questions focused mainly on adherence to medical prescriptions, comments about the rehabilitation program, and motivation for continuing it at home. |

• The analysis of interviews was supported by grounded theory methodology following which core categories and a hierarchic organization of issues were identified. | • Patients described an overall satisfaction with treatment. • Intensive rehabilitation was reported to counteract the symptoms of deterioration and disease progression. • Patients perceived physical improvements and functionality, which exceeded expectations. • Many patients also reported an improvement in their mood as a result of the rehabilitation. • The majority of patients expressed the intention to continue with the prescribed rehabilitation at home. |

Abbreviations: ADLs, activities of daily living; ALDS, Academic Medical Center linear disability score; BBS, Berg Balance Scale; CSI, Caregiver Strain Index; DBS, Deep Brain Stimulation; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life Group – five dimensions; FIM, Functional Independence Measure; HADs, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; QoL, quality of life; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Scale; MDS, Movement Disorder Society; MDT, Multidisciplinary Team; MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; NMSS, Non-Motor Symptom Scale; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PDNS, Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist; PDQ-39, 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire; PDSS, Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale; PMS, Global patient’s mood status; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SCOPA-PS, Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease – Psychosocial; SDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; SEADL, Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living; SF-36, Short Form 36-item health survey; SPDDS, Self-Assessment Parkinson’s Disease Disability Scale; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

The lack of a clear definition of advanced PD16 creates a further challenge. Furthermore, people who have been identified as having advanced PD are often not referred for advanced therapies,17 which can improve their motor function and QoL.18 These therapies – deep brain stimulation (DBS),19 subcutaneous apomorphine pump,20 and levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG; carbidopa–levodopa enteral suspension in the USA),21 – require specialized MDTs to ensure successful implementation. However, experience in establishing and working within such specialized MDTs is limited.

This paper reviews the literature and shares the extensive relevant experiences of the authors to help address gaps in clinical practice and guidelines concerning MDT management of advanced PD, timely referral of people with PD for advanced therapies, and implementation of advanced therapies (with special attention to LCIG therapy).

Literature search strategy and selection criteria

Studies were identified through a PubMed literature search using the following search terms: multidisciplinary/interdisciplinary/multispecialty AND Parkinson’s disease AND study. This yielded 90 hits – the abstracts were screened for suitability. Only studies investigating the impact of multidisciplinary care in people with PD were included. Reviews (systematic and other), nonrelevant articles, and studies in which only the protocol and study design were discussed were excluded from the results. The literature search was performed in July 2016.

Who is in the MDT?

The MDT comprises up to 20 different collaborating health care professionals centered on the person with PD and their caregiver, to provide comprehensive care to meet as many of the patient’s health and other needs as possible (Table 2).12,14,22 The involvement of a PD nurse specialist (PDNS),12,14,22,23 to offer support at the individual level, education to the wider community, and training of clinical and nonclinical staff,24 complements the interventions of the rest of the team to improve the QoL of people with PD and their caregivers.25

Table 2.

Members of the MDT listed by the European Parkinson’s Disease Standards of Care Consensus Statement and their role in the care and management of people with PD12

| MDT member | Role |

|---|---|

| General practitioner | To provide day-to-day clinical management |

| Movement disorder specialist/neurologist | To plan and monitor treatment |

| Geriatrician | To provide general in- and outpatient management |

| PDNS | To manage care and coordinate with the hospital and community services |

| Physiotherapist | To maximize functional ability |

| Speech and language therapist | To manage difficulties with speech, communication, eating, drinking, and swallowing |

| Occupational therapist | To advise on measures to retain independence |

| Nutritionist | To ensure optimal nutrition |

| Psychologist | To treat depression, other mental health problems |

| Pharmacists | To ensure supplies of specialist medications |

| Complementary therapists | To provide massage and relaxation therapies |

Note: Data from The European Parkinson’s Disease Standards of Care Consensus Statement.12

Abbreviations: PD, Parkinson’s disease; MDT, multidisciplinary team; PDNS, Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist.

As PD progresses to advanced PD,26 device-aided advanced therapies become an option to improve motor function and QoL.18 At this stage, additional members of the MDT include neurosurgeons and gastroenterologists with a special interest and expertise in managing people with advanced PD indicated for DBS or LCIG, respectively.

Roles and responsibilities within the MDT

The PD MDT composition and the roles/responsibilities of each member require clear definition so that they can work both individually and collaboratively to achieve a common set of treatment objectives. The involvement of different MDT members at any one time depends on the needs of the person with PD and their caregiver, and the stage of their disease. Effective interventions preserve the caregiver’s well-being, and allow people with PD to remain at home with appropriate assistance.9

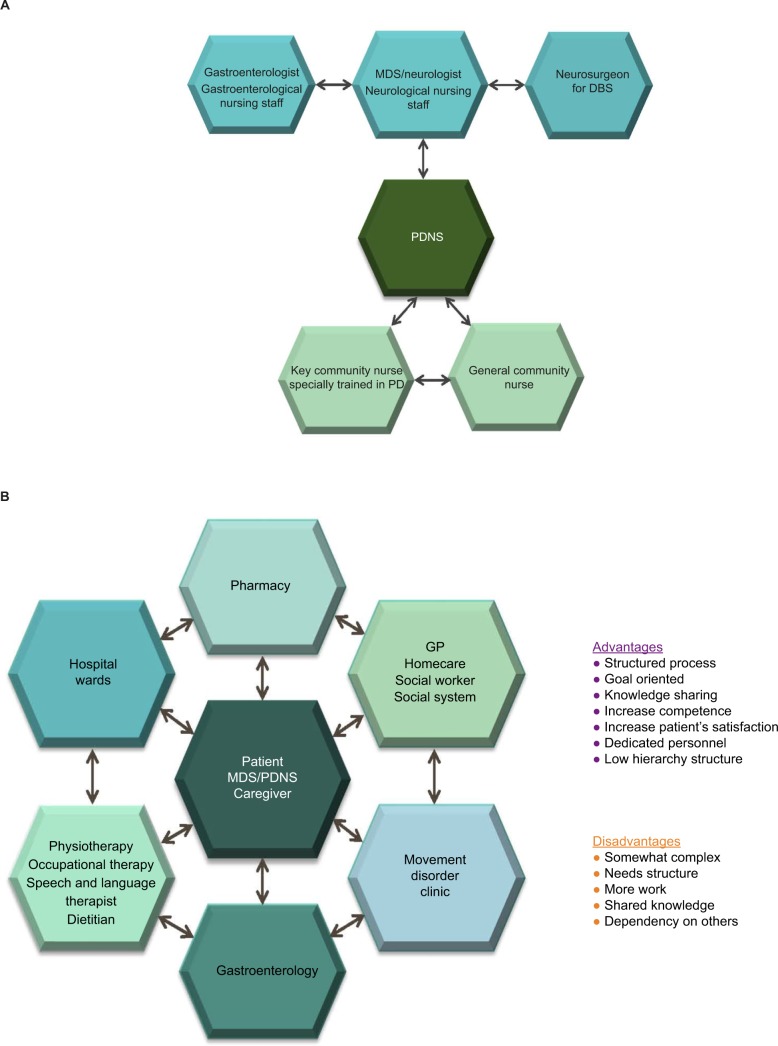

Ideally, various networks exist and interact within the MDT (Figure 1A). In Denmark, for example:

A triangular network exists for day-to-day management between general community nurses, a key community nurse trained in PD who can answer most day-to-day questions, and a hospital-based PDNS.

A vertical network provides nurses in the community with access to expert advice and information from the PDNS and neurologist.

Horizontal networks in the hospital facilitate treatment of advanced PD between movement disorder specialists (MDSs)/specialist neurologists, gastroenterologists, and neurosurgeons, and between nurses from different departments.

Figure 1.

Examples of multidisciplinary team networks aiming to provide comprehensive and collaborative care for people with PD.

Notes: (A) Network interaction within the PD multidisciplinary team in Denmark supporting information exchange about patients. (B) The Rigshospitalet Glostrup model.

Abbreviations: PD, Parkinson’s disease; DBS, deep brain stimulation; GP, general practitioner; MDS, movement disorder specialist; PDNS, Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist.

The complex, but not complicated, multidisciplinary Glostrup model (Figure 1B) depicts the interactions and networks between all members of the PD MDT with the person with PD, their caregiver, the MDS, and the PDNS at the center. A strong collaboration between hospital and community nurses is essential with this approach.

People with PD and their caregivers require clear information and education about their therapeutic options throughout the disease, including the possible advantages and disadvantages, to ensure that treatments are used appropriately to achieve the best possible QoL and motor function.17,27 The MDS and PDNS are experts in the provision of such information, and all newly diagnosed people with PD should be referred to a specialized MDT with a PDNS as soon as possible after diagnosis.17,24,27 The PDNS can then liaise with and involve the MDS and other members of the MDT as required.

The MDS and PDNS aim to provide seamless care and information and provide newly diagnosed people with PD with the opportunity to talk about and discuss the diagnosis in more detail. They can help them come to terms with the diagnosis, how it might affect them, and how they can manage it.24

Caregivers also play an important role in the team of individuals supporting people with PD. While offering assistance with activities of daily living, they are also involved with the management of PD-related tasks (appointments, medication) and treatment decisions. At all stages of the disease, treatment decisions should be made jointly between the person with PD, their caregiver, family, and health care practitioners.28 Greater involvement in treatment decisions leads to significantly greater satisfaction and distress relief in people with PD.29 Furthermore, engaging people with PD and their caregivers to understand PD and the therapies available could lead to improved adherence to therapy, as has been demonstrated in diabetes patients.30

A further role for the MDS and PDNS is to discuss advanced therapies with people with PD and their caregivers early in the disease course. To avoid “end-stage” perception, it is important they highlight that there may be a time when existing therapies are no longer effective, and at this point advanced therapies may offer much-needed improvements in QoL and motor function.21,31–33 They can then discuss with the MDS how to derive maximum benefit from such treatment when it becomes the appropriate option.

Identification of people with PD for advanced therapy, and selection and implementation of the appropriate therapy

Treatment with oral dopaminergic therapies usually controls motor symptoms in early PD, but as PD progresses it becomes less effective, resulting in motor and nonmotor fluctuations and dyskinesias.34 The reasons for this are poorly understood, but probably involve pharmacokinetic factors.35 The progression of PD has a substantial impact on health-related QoL.36 During long-term follow-up, deterioration in physical mobility has been shown to be the most important factor contributing to decline in health-related QoL.37 A relationship between QoL for the person with PD and the caregiver’s perceived burden has also been demonstrated.38 At this stage of PD, it is important to ensure timely referral to an MDS before complications develop and QoL deteriorates.17

Advanced therapies may be appropriate when motor fluctuations become refractory to adjustments in oral and transdermal medications and when such adjustments are complicated by the emergence (or worsening) of dyskinesias.39,40 Simplified criteria to help improve recognition of the advanced stages of PD despite an optimized oral drug regimen can include:

unpredictable fluctuations;

more than 2 hours “off ”-time/d;

over five doses of medication/d;

impaired activities of daily living.18

Raising awareness about when a person with PD might benefit from an advanced therapy is a key responsibility for the MDS. The PDNS, in providing individual care to alleviate the impact of PD on daily life, is well placed to assess whether a patient might derive more autonomy with an advanced therapy.41

Once the MDS has identified that a person with PD might benefit from an advanced therapy, he or she can discuss the options, advantages, and disadvantages of each treatment, and advise on how the advanced therapy can improve the patient’s symptoms. The PDNS can help the patient and their caregiver take an active role in the decision-making process,24,41 for example, by providing a portable test pump and tubing so that the person with PD can experience how it might feel to wear and carry it every day.

The PDNS and MDS aim to align the expectations of the person with PD and their caregiver with what can be achieved from a particular type of advanced therapy.

The regional MDT approach in the Netherlands (ParkinsonNet) improves quality of care and reduces health care costs

In the Netherlands, regional MDTs specialize in providing a particular type of advanced PD therapy.42 Such regional cooperation has improved the quality of care and reduced health care costs for people with PD.43

All teams meet together regularly to discuss those people with PD who might have an indication for advanced therapy in their area and to exchange experience and knowledge. These meetings involve 10–15 MDSs and 10–15 PDNSs from the university hospital and the larger regional hospitals in the area. Decisions are made on the most suitable advanced therapy for each individual with PD using a matrix (Table 3) that takes into account medical conditions, for example, impaired cognitive function. Recently published expert opinion recommendations give some guidance on the management of people with mild or moderate cognitive impairment.18

Table 3.

Matrix used in the Netherlands to help decide upon the most suitable advanced therapy for each individual with PD

| Factor | Apomorphine | LCIG | DBS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age >75 years | 0 | 0 | – |

| Postural instability | 0 | 0 | – |

| Hallucinations | −/+ | −/0 | − |

| ICD | −/+ | + | + |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | − | 0 | 0 |

| Dementia | 0 | 0 | − |

| Need to stop oral medication | − | + | − |

| Moderate depression | + | +/0 | − |

| Suicide attempts | 0 | 0 | − |

| Restless legs | + | + | 0/− |

| Weight gain | 0 | 0 | − |

Notes: +, factor strengthens the decision to select the device-aided therapy; 0, factor does not influence the decision; −, factor argues against selecting the device-aided therapy.

Abbreviations: PD, Parkinson’s disease; LCIG, levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel; DBS, deep brain stimulation; ICD, impulse control disorder.

ParkinsonNet (Nijmegen, the Netherlands) is also largely focused on “participatory medicine”, encouraging people with PD to take an active role in the management of their disease and act as partners in the decision-making process.28 They are then referred to a center, providing the chosen therapy, close to their home. To enable this collaboration, patients need to be well-informed and empowered to make a choice, through the provision of unbiased medical information presented in a way that can be easily understood.28 This collaboration requires physicians to “guide” patients, rather than telling them what to do.28 A decision aid to support people with PD make a choice about advanced therapies is being developed and was recently trialed with 19 patients.44 Overall, 100% of the participants stated that they would use the aid if faced with the choice, with 88% saying that the information was well balanced. The aid is currently being modified to include more first-hand patient experiences, and to include more practical information.44

ParkinsonNet has not only provided more joined-up care for people with PD centered around evidence-based recommendations and best practice guidelines, but also reduced health care costs by approximately €20 million each year, illustrating that informed patients make the right decisions.45

The Düsseldorf Parkinson MDT network approach in Germany improves MDT communication and increases the individual with PD’s confidence in innovative therapies

The Düsseldorf Parkinson network is another approach to the MDT management of PD.46 A university-hospital–based MDS together with a PDNS and a general neurologist jointly see and discuss patients attending the general neurologist’s outpatient clinic. A diagnostic and therapeutic treatment strategy, such as planning an advanced therapy, can usually be developed at the time. This leads to greatly improved interaction and communication between experts from the Movement Disorders Center and the general neurologist; and involvement of the general neurologist increases the individual with PD’s confidence in innovative therapeutic options. Treatment can then be initiated promptly to improve the individual’s QoL.

After the joint outpatient consultation, the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are carefully planned in close consultation with the cooperating specialized disciplines (eg, gastroenterology for LCIG, neurosurgery for DBS) before the patient’s admission to ensure optimal resource utilization and effective clinical treatment.

The network has recently incorporated an integrated care contract, which includes the following approaches:

If the patient agrees to a proposed hospital admission, for example, to carry out LCIG therapy or DBS, then the patient’s data are forwarded to the patient manager of the university hospital. The patient manager immediately arranges the inpatient stay, the relevant interdisciplinary consultation with other specialized disciplines (eg, gastroenterology, neurosurgery), and the admission appointment with the patient by telephone.

After the procedure, the patient is usually seen again at a joint consultation with their general neurologist, the MDS, and the PDNS to discuss and manage the new treatment. The PDNS may visit the patient at home up to four times during a 12-month period to offer further education or assistance in the handling of an invasive PD therapy.

The patient may receive a telemedicine care program,47 in which case patient-related data are passed to the authorized PDNS, who then schedules a 4-week treatment period after consulting the insurance provider and the patient.

Implementing LCIG therapy

LCIG is an effective treatment option for advanced PD that significantly improves patients QoL and motor fluctuations. It is approved for the treatment of advanced levodopa-responsive PD with severe motor fluctuations and hyperkinesia/dyskinesia when available combinations of Parkinson medicinal products have not given satisfactory results.48 For long-term administration, LCIG is administered with a portable pump directly into the jejunum by a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy49 with a jejunal extension tube (PEG-J).48,50 This alleviates the pharmacokinetic issues associated with oral levodopa–carbidopa, bypassing the often erratic gastric emptying in advanced PD.35 The PEG-J procedure requires close cooperation between the MDS, a gastroenterologist skilled in carrying out the procedure in patients with PD, and nurses in the neurology and gastroenterology departments.

Accessibility to the gastroenterologist, whose expertise is required before, during, and after the procedure, and to deal with any problems or questions that might arise, is key. Some gastroenterologists may not be familiar with the PEG-J tubing and connections required for LCIG therapy, and so time will be required for:

familiarization with the equipment and

to develop understanding of the dyskinesias that occur in PD to ensure they do not interfere with the procedure.

It is important to optimize PD medication before PEG-J placement in order to achieve a balance between patient rigidity and dyskinesia, and facilitate insertion.51,52

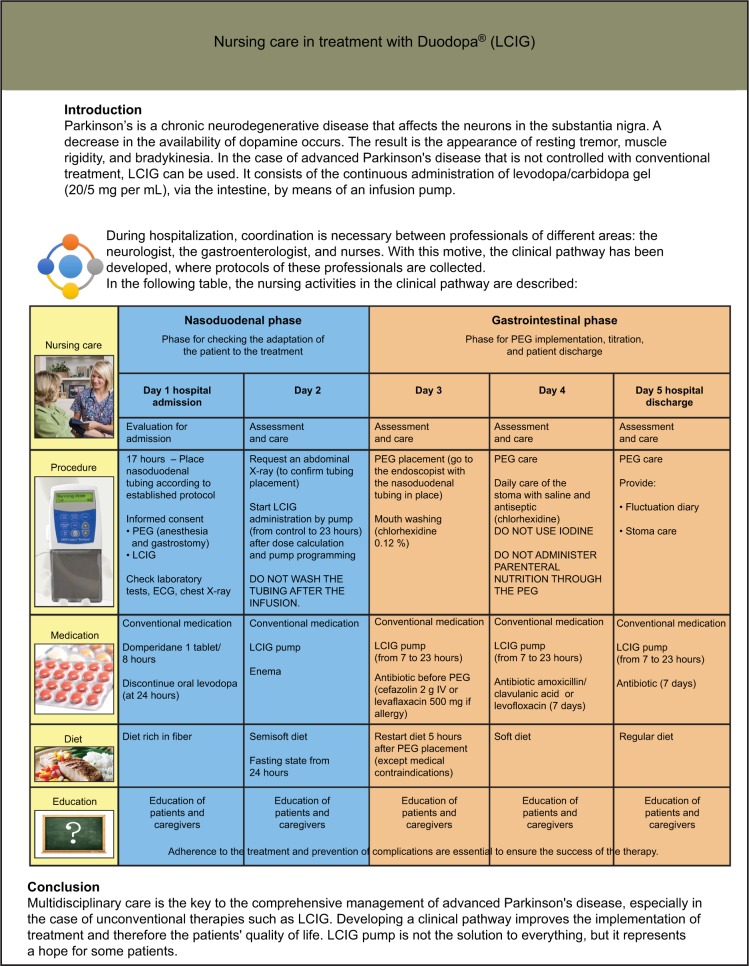

The PDNS ensures coordination between the person with PD, the caregiver, and all members of the MDT before, during, and after the procedure. It is useful to have an established protocol. In one center in Madrid, Spain (Hospital General Universidad Gregorio Marañón), a one-page wall-mounted illustrated protocol clarifies nursing roles and responsibilities throughout the titration process (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The one-page, wall-mounted illustrated titration protocol clarifying the role and responsibilities of nurses throughout the titration process at the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain.

Notes: This poster is one component of the hospital’s “clinical pathway” that coordinates the protocols for each role in the MDT. Steps of this protocol reflect regional use and not necessarily label instructions for this product. Courtesy from Drs Carmen Funes Molina and Francisco Grandas, (translated from Spanish).

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; ECG, electrocardiography; LCIG, levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel.

In Denmark, the nurses in the neurology department take much of the postprocedural responsibility and are trained to manage the PEG-J, though can seek assistance from nurses in the gastroenterology department. The person with PD and their caregiver are trained to handle the pump and the practicalities of the treatment. They are also provided with contact numbers for specially trained community nurses and the hospital-based PDNS, along with advice about who to call and when.

At German model institutions, experience has shown that it is essential that the collaborating gastroenterologist is a skilled interventional endoscopist who is familiar with the procedure, the pitfalls, and the potential complications. Before starting the 2-day test phase with a nasointestinal tube, PD patients are routinely examined using fiberendoscopic evaluation of swallowing, videofluoroscopy, functional transnasal endoscopy to investigate the esophageal phase of deglutition,53 high-resolution manometry, and endoscopy to assess the feasibility of the PEG-J procedure. However, most PEG-J placements worldwide are performed without this extensive workup.

Following standard operating procedures, and after a single dose of antibiotic intravenously, at least a transabdominal ultrasound should be performed to exclude anatomic problems, after which both nasointestinal tubes and PEG-J are placed on an inpatient basis. After successful implementation of the treatment, the patients are followed up in hospital, and at discharge, they are provided with domestic nursing staff to provide professional assistance.

A Canadian outpatient model significantly reduces the burden on limited health care resources

In Canada, an outpatient ambulatory model significantly reduces the cost for initiating LCIG and the burden on limited health care resources. It also offers greater flexibility in scheduling because it does not depend on the availability of an inpatient bed.54

In this model, a gastroenterologist is an integral part of the MDT and carries out a preprocedure consultation to screen for contraindications, to provide information on the insertion process and the risks and complications, and to obtain consent. The LCIG nurse (a hospital PD nurse trained in the LCIG pump system and titration) provides further information on the PEG-J and aftercare.

The PEG-J procedure is carried out on the outpatient endoscopy unit. The patient is under conscious sedation or given propofol for deep sedation, depending on clinician’s judgment and the level of dyskinesia. This involves close collaboration between the gastroenterologist, anesthesiologist, and movement disorder team. Appropriate placement of the J-tube is confirmed using a portable abdominal X-ray with contrast injected into the J-tube. The patient is discharged from the unit on recovery from the sedation. The next day, the gastroenterologist examines the stoma and confirms correct placement of the PEG-J in the ambulatory clinic.

Once the fistula tract of the PEG-J has matured, the patient returns for outpatient medication titration over a few days. The LCIG nurses titrate the LCIG dosage under the supervision of the neurologist and take a lead role in managing the pump; they are trained in basic stoma care and supported by the gastroenterologist.

The patients are followed up every 3 or 6 months, and the gastroenterologist examines the stoma and PEG-J placement at each visit.

It has proved beneficial for the trained gastroenterologist to train gastroenterologists in other centers and share best practices and learnings.

One consideration of this outpatient model is that patients who live at some distance from the health care center may find it difficult to attend the ambulatory clinic the following day and during the initial LCIG titrating phase. This can be overcome by providing accommodation in nearby housing or a hostel.

Discussion

The multifaceted nature of PD naturally lends itself to a multidisciplinary approach to care.55 A well-structured MDT can provide essential support in many areas of disease management, for example, with therapy decisions, which can become more complex as the disease progresses. Raising awareness about when a person with PD might benefit from an advanced therapy is a key responsibility for both the MDS and PDNS. The PDNS and MDS aim to align the expectations of the person with PD and their caregiver with what can be achieved from a particular type of advanced therapy. Through “participatory medicine” it is crucial that the MDT, while empowering people with PD and their caregivers to take an active role in management of their disease, provide unbiased information and advice as and when appropriate, tailoring it to the individual.28

Available studies show that people with PD and their caregivers benefit from joined-up multidisciplinary care, although the number of reports in this area is still limited and very few controlled studies are available.1–8,10,11,56–58 The key to the optimal management of people with PD at all stages of the disease, and successful implementation of advanced therapies, is an effective MDT approach, such as those models described in this paper. An optimal MDT structure can provide benefits for the patient and his or her caregiver, in addition to optimizing the success of treatment. With the increasing prevalence and burden of PD, and rising health care costs, the financial implications of such models are ever more important. In the Netherlands, regional MDTs that specialize in providing a particular type of advanced PD therapy (ParkinsonNet)42 have not only improved the quality of care but also decreased health care costs.43 In Germany, the Düsseldorf Parkinson network has led to greatly improved interaction and communication between experts from the Movement Disorders Center and the general neurologist, enabling more efficient initiation of advanced therapies. In Canada, the outpatient ambulatory model has been established for LCIG onboarding, to overcome the challenge and cost of obtaining inpatient beds.

Intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation interventions for people with PD are particularly effective at improving QoL and motor function.1–8,10,11,56–58 Although investment in such initiatives might prevent future costs attributed to disabling motor symptoms (eg, falls, loss of independence),58 innovative solutions should be considered to ensure such interventions can continue in the long-term, such as the Düsseldorf Parkinson network telemedicine care program. Not only do telemedicine approaches offer cost savings, they also have the benefit of opening up multidisciplinary care for people with PD who have limited access to specialist centers.59 While there are few studies of telemedicine in PD, schemes are on the increase enabling a better standard of care for patients in their homes or in remote areas.59,60 Furthermore, valid remote assessments of people with PD have been performed, and a high degree of patient satisfaction was reported with these studies.59,60

There is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to multidisciplinary care for people with PD; however, the models and studies discussed in this review may be adapted on a country/region/area basis. In countries lacking specialist MD services, a smaller, more localized MDT may be more realistic, with skilled physicians, who have experience in PD, initiating advanced therapies. Flexibility around implementing such approaches will increase access to multidisciplinary care for more people with PD, subsequently improving disease management, and ultimately patient and caregiver QoL.

Limitations

Limitations of this review include the lack of a systematic literature search to identify relevant studies. Furthermore, very few published, controlled studies exist to quantify the effect on multidisciplinary interventions in PD. Finally, there is a lack of clinical guidelines in the subject area; hence, the recommendations provided here are informed by the clinical experience of the authors.

Conclusion

The advantages of an MDT approach are clear and have been documented in several small studies, but larger scale, controlled trials are required to fully understand the benefits. Given the chronic nature of PD, and the difficulties many patients face traveling to appointments, particularly those with advanced disease, it is imperative that future studies consider innovative approaches to enable wider access to MDT care.

Based on the available literature and expert clinical experience of authors, key recommendations for the MDT approach for people with PD are:

to set up a close structured collaboration of different health care professionals working in a fixed network structure;

to refer people with PD to established MDT centers (where available) in a timely manner;

to establish regular meetings with treatment-responsible doctors and the MDT for interdisciplinary exchange and learning to optimize individual treatment and evaluate treatment options;

to ensure treatment decisions are agreed jointly between people with PD, their caregiver, family, and health care professional;

to include specialists outside of neurology from adjuvant medical departments as necessary when implementing advanced therapies.

Finally, the PDNS, a robust practical protocol that states who is doing what and when, and an effective network involving the community neurologist for training or consultation purposes are also pivotal to the success of the PD MDT.

Acknowledgments

This review was funded by AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL, USA. AbbVie participated in the writing, reviewing, and approving this paper. No payments were made to the authors for the development of this manuscript, and all authors approved the final version. Lindy van den Berghe and Emma East of Lucid Group, Burleighfield House, Buckinghamshire, UK, provided medical writing and editorial support to the authors in the development of this manuscript; financial support for these services was provided by AbbVie.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Pederson SW is a member of advisory boards for Ipsen, Allergan, Almira, Abbott, AbbVie, Sativex and has no share porfolio in medical companies. PSW also received lecture grants from Ipsen, AbbVie. van Laar T has received speaker fees from Britannia Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, and Medtronic and also a research grant from AbbVie. Suedmeyer M has received grants and/or honoraria for consultancy from Teva, Medtronic, St Jude Medical, Novartis, Meda, and Abbvie. Liu LWC acts as a speaker and is on the advisory board of Abbvie, Allergan Canada, Takeda, and Actavis. Domagk D has received honoraria for lectures from Olympus and consultancy fees from Hitachi Medical Systems and AbbVie. Forbes A is an independent consultant PDNS to AbbVie. Onuk K, Bergmann L, and Yegin A are employees of AbbVie, holding stock/stock options. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Carne W, Cifu D, Marcinko P, et al. Efficacy of a multidisciplinary treatment program on one-year outcomes of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2005;20(3):161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carne W, Cifu DX, Marcinko P, et al. Efficacy of multidisciplinary treatment program on long-term outcomes of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(6):779–786. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2005.03.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo L, Jiang Y, Yatsuya H, Yoshida Y, Sakamoto J. Group education with personal rehabilitation for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36(1):51–59. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100006314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trend P, Kaye J, Gage H, Owen C, Wade D. Short-term effectiveness of intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(7):717–725. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr545oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Marck MA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, Overeem S, Munneke M, Guttman M. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2013;28(5):605–611. doi: 10.1002/mds.25194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis T, Katz DI, White DK, DePiero TJ, Hohler AD, Saint-Hilaire M. Effectiveness of an inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation program for people with Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2008;88(7):812–819. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tickle-Degnen L, Ellis T, Saint-Hilaire MH, Thomas CA, Wagenaar RC. Self-management rehabilitation and health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2010;25(2):194–204. doi: 10.1002/mds.22940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Marck MA, Munneke M, Mulleners W, et al. Integrated multidisciplinary care in Parkinson’s disease: a non-randomised, controlled trial (IMPACT) Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(10):947–956. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Forjaz MJ. Quality of life and burden in caregivers for patients with Parkinson’s disease: concepts, assessment and related factors. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(2):221–230. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wade DT, Gage H, Owen C, Trend P, Grossmith C, Kaye J. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people with Parkinson’s disease: a randomised controlled study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(2):158–162. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White DK, Wagenaar RC, Ellis TD, Tickle-Degnen L. Changes in walking activity and endurance following rehabilitation for people with Parkinson disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The European Parkinson’s Disease Standards of Care Consensus Statement. 2012. [Accessed July 6, 2016]. Available from: http://alt.kompetenznetz-parkinson.de/EPDA_Parkinson_s_standard_nsus_Statement_Vol_I.pdf.

- 13.Conditions NCCfC . Parkinson’s Disease: National Clinical Guideline for Diagnosis and Management in Primary and Secondary Care. London, UK: Royal College of Physicians; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bloem BR, de Vries NM, Ebersbach G. Nonpharmacological treatments for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(11):1504–1520. doi: 10.1002/mds.26363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, Steeves TD. The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014;29(13):1583–1590. doi: 10.1002/mds.25945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coelho M, Ferreira JJ. Late-stage Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(8):435–442. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lokk J. Lack of information and access to advanced treatment for Parkinson’s disease patients. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:433–439. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S27180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odin P, Ray Chaudhuri K, Slevin JT, et al. Collective physician perspectives on non-oral medication approaches for the management of clinically relevant unresolved issues in Parkinson’s disease: consensus from an international survey and discussion program. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(10):1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perestelo-Perez L, Rivero-Santana A, Perez-Ramos J, Serrano-Perez P, Panetta J, Hilarion P. Deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol. 2014;261(11):2051–2060. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trenkwalder C, Chaudhuri KR, Garcia Ruiz PJ, et al. Expert Consensus Group report on the use of apomorphine in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease – clinical practice recommendations. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(9):1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olanow CW, Kieburtz K, Odin P, et al. Continuous intrajejunal infusion of levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, double-dummy study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70293-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell GK, Tieman JJ, Shelby-James TM. Multidisciplinary care planning and teamwork in primary care. Med J Aust. 2008;188(8 Suppl):S61–S64. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkinson’s Disease Society . Competencies: An Integrated Career and Competency Framework for Nurses Working in PD Management. London, UK: Parkinson’s Disease Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacMahon DG. Parkinson’s disease nurse specialists: an important role in disease management. Neurology. 1999;52(7 Suppl 3):S21–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacMahon DG, Thomas S. Practical approach to quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: the nurse’s role. J Neurol. 1998;245(Suppl 1):S19–S22. doi: 10.1007/pl00007732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alves G, Wentzel-Larsen T, Aarsland D, Larsen JP. Progression of motor impairment and disability in Parkinson disease: a population-based study. Neurology. 2005;65(9):1436–1441. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183359.50822.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimbo T, Goto M, Morimoto T, et al. Association between patient education and health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(1):81–89. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015306.59840.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Eijk M, Nijhuis FA, Faber MJ, Bloem BR. Moving from physician-centered care towards patient-centered care for Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19(11):923–927. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grosset KA, Grosset DG. Patient-perceived involvement and satisfaction in Parkinson’s disease: effect on therapy decisions and quality of life. Mov Disord. 2005;20(5):616–619. doi: 10.1002/mds.20393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunha M, Andre S, Granado J, Albuquerque C, Madureire A. Empowerment and adherence to the therapeutic regimen in people with diabetes. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;171:289–293. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deuschl G, Schade-Brittinger C, Krack P, et al. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):896–908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez-Martin P, Reddy P, Katzenschlager R, et al. EuroInf: a multicenter comparative observational study of apomorphine and levodopa infusion in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(4):510–516. doi: 10.1002/mds.26067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuepbach WM, Rau J, Knudsen K, et al. Neurostimulation for Parkinson’s disease with early motor complications. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(7):610–622. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bjornestad A, Forsaa EB, Pedersen KF, Tysnes OB, Larsen JP, Alves G. Risk and course of motor complications in a population-based incident Parkinson’s disease cohort. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;22:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rascol O. Extended-release carbidopa-levodopa in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(4):325–326. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlsen KH, Tandberg E, Arsland D, Larsen JP. Health related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: a prospective longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69(5):584–589. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.5.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forsaa EB, Larsen JP, Wentzel-Larsen T, Herlofson K, Alves G. Predictors and course of health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(10):1420–1427. doi: 10.1002/mds.22121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Violante M, Camacho-Ordonez A, Cervantes-Arriaga A, Gonzalez-Latapi P, Velazquez-Osuna S. Factors associated with the quality of life of subjects with Parkinson’s disease and burden on their caregivers. Neurologia. 2015;30(5):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaudhuri KR, Rizos A, Sethi KD. Motor and nonmotor complications in Parkinson’s disease: an argument for continuous drug delivery? J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2013;120(9):1305–1320. doi: 10.1007/s00702-013-0981-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Worth PF. When the going gets tough: how to select patients with Parkinson’s disease for advanced therapies. Pract Neurol. 2013;13(3):140–152. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2012-000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hellqvist C, Bertero C. Support supplied by Parkinson’s disease specialist nurses to Parkinson’s disease patients and their spouses. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;28(2):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keus SH, Oude Nijhuis LB, Nijkrake MJ, Bloem BR, Munneke M. Improving community healthcare for patients with Parkinson’s disease: the dutch model. Parkinsons Dis. 2012;2012:543426. doi: 10.1155/2012/543426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bloem BR, Munneke M. Revolutionising management of chronic disease: the ParkinsonNet approach. BMJ. 2014;348:g1838. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bloem BR, Faber MJ, Nijhuis FA, Radder DL. Designing a decision aid for patients in advanced Parkinson’s disease: the user test experiences. Mov Dis. 2015;30(Suppl 1):185. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgan J. A seat at the table for people with Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(11):1077–1078. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00246-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sudmeyer M, Volkmann J, Wojtecki L, Deuschl G, Schnitzler A, Moller B. Tiefe Hirnstimulation – Erwartungen und Bedenken. Bundesweite Fragebogenstudie mit Parkinson-Patienten und deren Angehörigen [Deep brain stimulation – expectations and doubts. A nationwide questionnaire study of patients with Parkinson’s disease and their family members] Nervenarzt. 2012;83(4):481–486. doi: 10.1007/s00115-011-3400-x. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marzinzik F, Wahl M, Doletschek CM, Jugel C, Rewitzer C, Klostermann F. Evaluation of a telemedical care programme for patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(6):322–327. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.120105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duodopa® (levodopa and carbidopa monohydrate) intestinal gel [summary of product characteristics] North Chicago, IL: AbbVie; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pedersen SW, Clausen J, Gregerslund MM. Practical guidance on how to handle levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel therapy of advanced PD in a movement disorder clinic. Open Neurol J. 2012;6:37–50. doi: 10.2174/1874205X01206010037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lundqvist C. Continuous levodopa for advanced Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(3):335–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez HH, Standaert DG, Hauser RA, et al. Levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel in advanced Parkinson’s disease: final 12-month, open-label results. Mov Disord. 2015;30(4):500–509. doi: 10.1002/mds.26123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lew MF, Slevin JT, Kruger R, et al. Initiation and dose optimization for levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel: insights from Phase III clinical trials. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(7):742–748. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Domagk D, Lenz P, Heuwing K, et al. Transnasal endoscopic evaluation of swallowing: functional esophagoscopy using and ultrathin video endoscope in neurogenic dysphagia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(5):AB515. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fasano A, Liu LW, Poon YY, Lang AE. Initiating intrajejunal infusion of levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel: an outpatient model. Mov Disord. 2015;30(4):598–599. doi: 10.1002/mds.26195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prizer LP, Browner N. The integrative care of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. J Parkinsons Dis. 2012;2(2):79–86. doi: 10.3233/JPD-2012-12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frazzitta G, Maestri R, Ferrazzoli D, et al. Multidisciplinary intensive rehabilitation treatment improves sleep quality in Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Mov Disord. 2015;2:11. doi: 10.1186/s40734-015-0020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giardini A, Pierobon A, Callegari S, Bertotti G, Maffoni M, Frazzitta G. Towards proactive active living: patients with Parkinson’s disease experience of a multidisciplinary intensive rehabilitation treatment. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016 Jun 1; doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.16.04213-1. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monticone M, Ambrosini E, Laurini A, Rocca B, Foti C. In-patient multidisciplinary rehabilitation for Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2015;30(8):1050–1058. doi: 10.1002/mds.26256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Achey M, Aldred JL, Aljehani N, et al. The past, present, and future of telemedicine for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29(7):871–883. doi: 10.1002/mds.25903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willows T, Dizdar N, Nyholm D, et al. Telemedicine facilitates efficient and safe home titration of levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31(Suppl 2):S1–S697. [Google Scholar]