Abstract

This review describes and summarizes student pharmacists’ substance use behavior in the United States. Current literature indicates that there are problems with alcohol and other drug use among student pharmacists. Although researchers have found variations in the type and rate of reported substance use, significant proportions of student pharmacists were identified as being at high risk for substance use disorders (SUDs). Findings from this review suggest that pharmacy schools should encourage and stimulate more research in order to implement effective screening and early intervention programs in an effort to address this important student health issue.

Keywords: substance use disorders, substance use behaviors, student pharmacists, colleges of pharmacy

INTRODUCTION

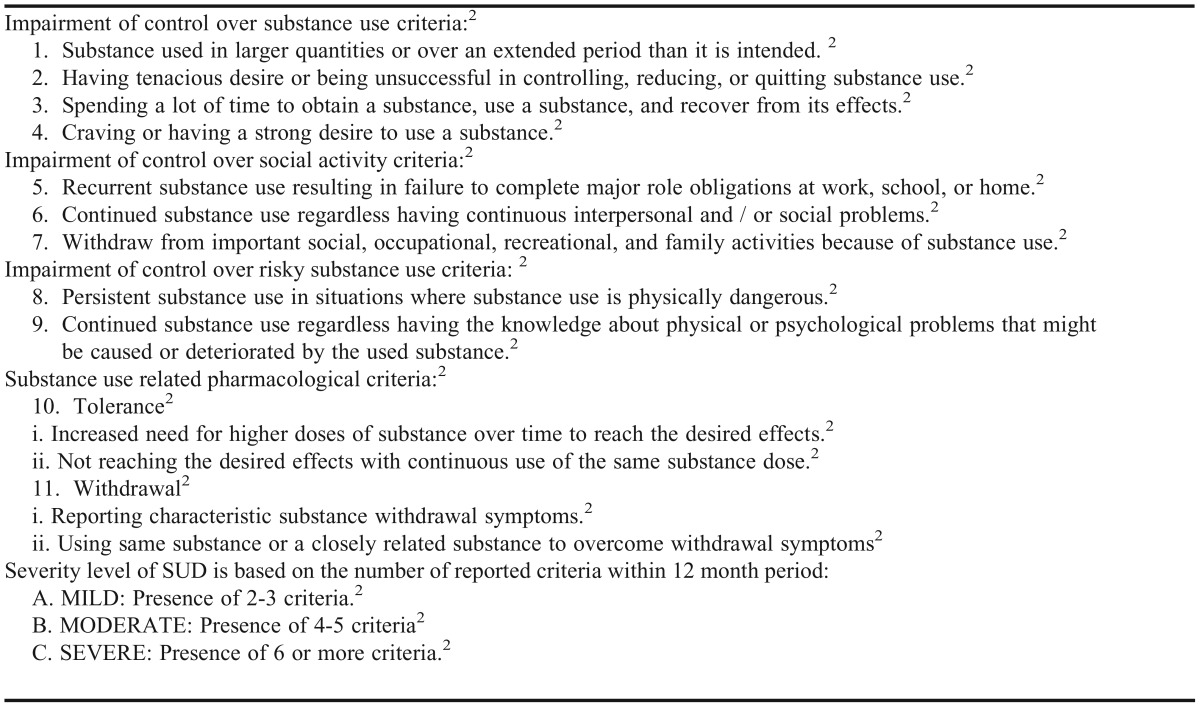

Healthcare professionals are at risk for developing substance use disorders (SUDs).1 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), SUD is the updated term that embraces the two interrelated conditions of substance abuse and dependence.2-4 The term addiction was completely eliminated from the updated SUD terminology in the DSM-5 because of its debatable definition and associated stigma.3 The unidimensional disorder (SUD) is defined as a “problematic pattern of behaviors related to the use of substance” that can lead to significant impairment or distress.2-5 Table 1 lists SUD criteria specified in the DSM-5 manual. SUD clinical and functional impairments may include health problems, disabilities, and being unable to meet significant obligations at home, school, and/or work.4,5 The most common substances associated with SUD in the United States include alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, stimulants, hallucinogens, and opioids.2,5

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorders (SUD)2

In 2003, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) stated that 8% to 12% of healthcare workers had chemical dependencies.6 Approximately 10% to 15% of healthcare professionals are estimated to misuse alcohol or drugs at some time during their career.1 Among healthcare professionals, pharmacists play a central role in medical care and are medication experts, yet they are highly vulnerable to SUDs.1 Research shows that approximately 40% of pharmacists have reported nonmedical use of prescribed drugs.7-10 In addition, a higher percentage of pharmacists report lifetime use of an opioid or anxiolytic (approximately 25% and 14%, respectively) as compared to nurses (15% and 8%, respectively).11 As a result, the healthcare process and patients’ health might be threatened.

Substance use behaviors and/or disorders may develop during preprofessional years (ie, college years or even before).12,13 In one study, 88% of pharmacy practitioners who admitted lifetime use of nonprescribed drugs began to use drugs during college.7 In general, substance use behaviors among college students have been a concern for many years. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), college students are more likely than their same age group (18-22 years) counterparts to report alcohol use.14 Higher rates of current (within the past 30 days), binge (5 or more drinks at the same time or within 2 hours on one or more days in the past month), and heavy (5 or more drinks on the same occasion on 5 or more days in the past month) alcohol use were reported by college students as compared to rates reported by young adults not enrolled in college.15 In addition to alcohol, research shows that college students commonly report use of other substances. For example, in a 2014 national survey, 22.3% of college students reported using illicit drugs in the past month.15

Previous research also suggests that healthcare professional students are a significant subsample of the college student population that is at higher risk for problematic substance use behaviors.16-18 However, less research has examined substance use among student pharmacists in comparison to other healthcare professional students.8,9,18,19 Substance use and its disorders can cause personal disruption and loss of productivity at school and professionally. The primary purposes of this literature review were: to highlight what is known about substance use behaviors among student pharmacists, and to identify factors that might influence problematic substance use behaviors among student pharmacists.

METHODS

This review includes studies completed within US colleges and universities identified through multiple databases (PubMed, Web of Knowledge, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO). Searches were conducted using the key words “substance use” OR “alcohol” OR “caffeine” OR “cannabis” OR “hallucinogen” OR “inhalants” OR “opioids” OR “sedatives” OR “hypnotics” OR “anxiolytics” OR “stimulants” OR “tobacco” AND “student pharmacists” OR “pharmacy schools” in the title and/or abstract. Limitations imposed within the search included English language and research conducted in human subjects. Further, cited references in all articles obtained by the aforementioned databases were reviewed. For the purpose of this review, any article on student pharmacists’ substance use behaviors was included and the focus was on substance use rates or levels (quantity and frequency of substance consumption), motives for any substance use, and substance use-related problems (negative outcomes).

FINDINGS

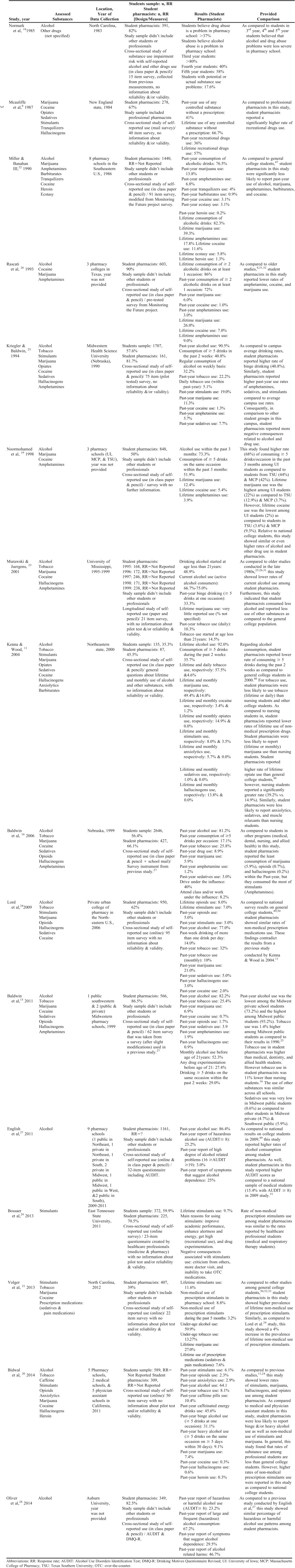

The literature search identified 16 studies. Thirteen articles assessed student pharmacists’ use of various substances,8,11,15,16,18-26 two articles solely focused on alcohol use,27,28 and one article examined only stimulants use.29 Table 2 summarizes the studies found through this search. The following paragraphs summarize the findings of these studies by substance type.

Table 2.

Key Studies That Assess Substance Use Patterns Among Student Pharmacists

Previous researchers primarily focused on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among student pharmacists. Alcohol was identified as the most used substance by student pharmacists.16,22 Problematic alcohol use was reported in a significant number of reviewed studies.11,16,18,27,28,30 In two recent studies, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to evaluate alcohol use patterns among student pharmacists.27,28 These studies showed similar results with approximately 25% of participants reporting hazardous or harmful drinking (AUDIT score ≥8). Binge drinking (consumption of 5 or more drinks in one occasion) also was assessed in previous studies.16,19,30 Results from two studies found that approximately 30% of student pharmacists had at least one binge drinking episode during the preceding 2 weeks.16,30 In another study conducted by Kenna and Wood, 36% of student pharmacists reported binge drinking within the past 2 weeks.11 A more recent study conducted by Bidwal and colleagues found similar results with 31% of respondents reporting binge alcohol use within the past-year.20

Fewer studies have investigated tobacco use among student pharmacists.11,16,30 Some researchers included questions within their surveys to assess tobacco use as a covariate that might influence student pharmacists’ use of other substances.20,23-25,27 Kenna and Wood found that approximately 58% of student pharmacists reported a lifetime tobacco use.11 Between 1990 and 2011, past-year tobacco use ranged between 8.1%-32%.20,24 While the most recent study conducted by Bidwal and colleagues in 2011 reported the lowest percentage of past-year tobacco use (8.1%),20 the highest percentage (32%) was reported by Lord and colleagues based on data collected in 2006.24 For regular tobacco use, Lord a reported that 10% of student pharmacists used tobacco a few times a month or even more.24 Murawski and Juergens found similar results with approximately 10% of student pharmacists reporting daily tobacco use (data collected between 1995 and 1999).23 However, other reports based on data collected in 2000 and 1990 showed 4.6% and 5.1% of daily tobacco use among student pharmacists, respectively.11,25

Caffeine Use

The search identified only one study that investigated caffeine use among student pharmacists.20 In a study of student pharmacists’ use of stimulants, Bidwal and colleagues found that 45.6% used caffeinated energy drinks and 10.4% used caffeine pills during the past year.20

Marijuana Use

Since 1990, marijuana was identified as the second most used substance after alcohol by student pharmacists.8,11,22 Rates of current marijuana use in recent studies ranged from 6%-21%, and rates for lifetime use were between 14% and 33%.11,20,24,30 As an example, Lord and colleagues found that 21% of student pharmacists reported the use of marijuana in the preceding year.24 Among these students, 5% reported using marijuana regularly on a monthly basis.24 However in studies conducted before 1993, researchers found higher rates of current (between 14% and 28%) and lifetime (between 39% and 52%) marijuana use among student pharmacists.8,26,31,32 Notably, the literature suggests a reduction in the rates of past-year marijuana use among student pharmacists (from 21%24 to 7.4%)20 based on data collected in 2006 and 2011).

Nonmedical Use of Prescription Drugs

Nonmedical use of prescription drugs was described as any use of prescription drugs without a legal prescription, or the use of prescribed medications in ways other than prescribed by healthcare providers, such as taking higher doses or changing route of administration.8,20,21,24 In late 1980s, a significant proportion of student pharmacists reported lifetime (66.7%) and past-year (41%) use of controlled substances without a legal prescription.8 Specific classes of drugs misused during pharmacy school years are discussed below.

Prescription Stimulants.

A small but significant proportion of student pharmacists reported misusing prescription stimulants.8,16,24,25 The most commonly reported stimulants used by student pharmacists include dextro-amphetamine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate.20,24,29 Five percent to 19% of respondents disclosed their current (within the past-year) nonmedical use of prescription stimulants.11,24,25 In 2004, Kenna and Wood stated that prescription stimulants were highly or frequently used by student pharmacists; 3.5% of their study respondents used them on a monthly basis.11 A recent study found that approximately 9% of student pharmacists used stimulants at some time during their college years, and 3.2% reported nonmedical use within the past 5 months.21 Other studies found that between 7% and 9.7% of student pharmacists reported a lifetime nonmedical use of prescription stimulants.20,24,29 Lord and colleagues24 found a 7% lifetime stimulants use in 2009. However, in a more recent study, Volger and colleagues21 found a 11.6% lifetime stimulants use.

Prescription Opioids.

Reported rates of misuse of prescription opioids among student pharmacists range between 8% and 15% (lifetime),10,28 and 1% to 6% (current use).11,20,24,30 With respect to the two most recent reports (data collected in 2006 and 2011), past-year prescription opioid misuse was reported by 5% and 2.3% of student pharmacists, respectively.20,24 Rates of past-year prescription opioid misuse in student pharmacists increased from 1.7%30 in 1999 to 5%24 in 2006. However in 2011, past-year misuse of prescription opioids was reported by only 2.3% of student pharmacists.20

Other Illicit Drugs Use

The literature search found mixed results regarding the use of other illicit drugs such as cocaine, ecstasy, heroin, and hallucinogens among student pharmacists. A majority of studies found that no more than 3% of student pharmacists reported lifetime or current use of cocaine, ecstasy, heroin, or hallucinogens.16,20,22,24,30 However, Miller and Banahan found lifetime use rates of 11.6% for cocaine and 5.8% for ecstasy among student pharmacists in 1990.22 Similarly, Rascati and colleagues found that 7% of students reported lifetime use of cocaine in 1993.26 A more recent study reported a significantly higher percentage (13.8%) of lifetime hallucinogen use among student pharmacists.11

Potential Factors Influencing Alcohol and Other Drug Use Behaviors

Age of first use.

Evidence suggests many student pharmacists began substance use and/or experimentation at an early age.23,24,27,28,30 Some studies report underage alcohol use by student pharmacists, in one study, as early as 10 years.23,27,30 In a study conducted in 1999, Baldwin and colleagues reported that more than half of study participants used alcohol on a monthly basis before the age of 21 years.30 Previous research also documented drug experimentation at very early ages (in junior high school, high school, or at any age before 21 years).24,30 Approximately 28% of student pharmacists reported drug experimentation at an age less than 21 years.30 In 2008, Lord and colleagues found that approximately 5% and 4% of study respondents indicated their use of opioids and stimulants at ages less than 21 years, respectively.24

Gender.

Despite the dominance of female enrollments in pharmacy schools, male gender was a significant predictor of substance use behaviors in most studies.11,24,27,28 Oliver and colleagues and English and colleagues observed that male participants were statistically more likely to report hazardous or harmful alcohol use (score 8 or more on the AUDIT) compared to their female counterparts.27,28 Similarly, being a male was identified as a significant predictor for reporting use of opioids in the past year. 24

Family history.

Significant percentages of student pharmacists reported having family members with SUDs.23 Student pharmacists with family histories of alcohol and/or drug problems were more likely to have substance use-related behavioral problems (eg, reported a high lifetime and/or past-year use) than their peers from families with no reported alcohol or drug use problems.11,25 Notably, all of these studies were based on students’ perceptions of family-members behaviors, which may have been confounded by the respondent’s own drug and alcohol use and perceived norms.

Access to prescription drugs.

Concerning student pharmacists’ access to controlled drugs, the vast majority of those who reported nonmedical use of prescription drugs, acquired these drugs illegally (with no valid prescriptions).24 Easy access to prescription drugs was reported by student pharmacists.8,11 Where these drugs were acquired, with students indicating worksite settings (community and/or outpatient pharmacies), school, and friends as the primary sources of drugs.8,20,24

Other potential factors.

Several other factors such as coping with stress, performance enhancement, self-treatment and recreational purposes have been associated with student pharmacists’ substance use. Student pharmacists have reported higher levels of stress as compared to the general adult population.18,20,33,34 Alcohol use may be employed as a coping strategy to deal with stress among student pharmacists.16,28,34,35 Regarding prescription stimulants, student pharmacists indicated that these drugs were primarily used to enhance performance (alertness and consentration) at school or work.21,24,29 Self-treatment was the most commonly reported reason for using prescription opioids.24 Specifically, student pharmacists reported using opioids to relieve stress or relax (29%), deal with chronic pain (23%), improve sleep (20%), and manage depression (11%).24 Finally, recreational use was among the most commonly reported reasons for illicit drug use (eg, marijuana) by student pharmacists.8,21,24

Substance Use Related Outcomes and Student Pharmacists’ Perceptions

Researchers have found negative outcomes associated with student pharmacists’ substance use. These negative outcomes can be classified as educational (eg, attending class under the influence,16,22,25,27,30 missing classes,25 receiving poor grades or evaluations16,20,26 ), risky-health behavioral (eg, unintended sexual contact,19,23,27 driving under influence or joining intoxicated driver,16,20,30 experiencing blackouts16,30), and professional (eg, taking care of patients while intoxicated,16,25,30 missing work or going to work while intoxicated,16,22,25,27,30 dealing with legal charges16,25,30). One study showed that student pharmacists had the highest rates of negative outcomes (eg, missing class or work, attending class or work while intoxicated, receiving lower grades or evaluation, dealing with legal and financial problems, facing marital and relationship problems, and taking care of patients while intoxicated) related to substance use among students from all other healthcare professional programs (dentistry and allied health).25

Previous studies also indicated that student pharmacists have concerns regarding the extent to which substance use is addressed in pharmacy schools.18,25 Approximately 34% of student pharmacists believed that prescription drug misuse is a critical issue that needs to be seriously reviewed.21 A substantial proportion of student pharmacists reported that their knowledge about substance use and SUD was insufficient.23,26,30 In a study conducted in 1999, Baldwin and colleagues found that only 9% of student pharmacists considered the available school’s resources (eg, health counseling groups) as the first choice when seeking assistance for alcohol or drug use problems.30 In addition, student pharmacists have indicated that there is a lack of policies regarding substance use, impairments, and recovery in pharmacy schools (eg, treatment confidentiality and students’ accountability).23,30

Methodological Considerations

The reviewed studies have methodological issues that warrant discussion. First, all reviewed studies relied on self-reported data,11,16,20,21,24,27,28,30 which may be subject to “reporting bias.” There were no attempts to cross validate self-reported data with other measurements of substance use (eg, biological tests or standardized screening tools). Student pharmacists’ future careers are affected by documented substance use problems (eg, licensing and practice regulations). Therefore, students may be more likely to underreport substance use behaviors. Second, previous research was not consistent in defining and measuring substance use behaviors among student pharmacists. For example, binge drinking was defined differently in 6 out of 9 studies 11,15,16,19,20,23-26 Several of the reviewed studies evaluated substance use over different time periods (eg, during the past 2 weeks,11,25 past 3 months,19 over the past year16,24). Furthermore, many of the studies used substance use measures that were not rigorously developed/tested, or failed to provide information regarding the measures’ psychometric properties (eg, reliability, validity).8,11,20,21,23-25 These measurement issues may limit the ability to: obtain accurate assessments of problematic substance use among student pharmacists, evaluate the longitudinal change in student pharmacists’ behavior of substance use, and compare and contrast results across study populations. Finally, there is a general lack of information in the literature regarding student pharmacists’ substance use. The majority of reviewed studies were conducted before 2010. Only 5 studies presented data collected within or after 2010 (5 years before conducting this review).20,21,27-29 Because of this, older publications (9 studies with data collected before 2000) formed the bulk of available literature.

DISCUSSION

Problematic substance use behaviors among students at US pharmacy schools represent a significant issue for the pharmacy profession and US healthcare system.1 There is a relative dearth of recent research studies in the literature regarding the substance use behaviors of student pharmacists. This is the first study to comprehensively review the available literature on substance use behaviors among student pharmacists in the United States. Findings from this review highlight the existence of substance use behaviors in this population. Problematic alcohol use (hazardous and harmful use) was evident in student pharmacists and student pharmacists reported other drug use (eg, stimulants, opioids, marijuana, sedatives, hallucinogens, anxiolytics, heroin, and cocaine) within the past year.20,21,24,27,28 This literature review provides pharmacy school stakeholders (eg, school administrators, program coordinators, and program directors) with current and historical information regarding alcohol and drug use among student pharmacists. Given that student pharmacists are the professional pharmacists of tomorrow, emphasis should be placed on intervening on these problematic behaviors to prevent situations that may jeopardize future healthcare processes and outcomes.

Based on the DSM-5 criteria for a SUD, results from previous research suggest that some student pharmacists may meet the diagnostic criteria for mild or even moderate SUDs. Several studies reported data related to the “impairment of control over substance use criteria” (Table 1). For example, high percentages of student pharmacists reported consuming large quantities of alcohol (eg, binge drinking or hazardous consumption) in the most recent studies (those published after 2010).20,27,28 Furthermore, one study found that 3.2% of student pharmacists used prescription stimulants for nonmedical purposes during the past 5 months.21 In addition, student pharmacists also reported negative outcomes related to substance use (eg, receiving poor grades or evaluations because of their substance use),11 which correspond to the impairment of control over social activity criteria. Student pharmacists who indicated substance use also were more likely to report driving under the influence or joining an intoxicated driver (ie, impairment of control over risky substance use criteria). 20 Collectively, these findings represent potential indicators for existing SUD in student pharmacists.

The evidence is mixed regarding the comparison between student pharmacists’ substance use behaviors and other healthcare students’ behaviors.11,16,20,25,29 For example, one study showed that student pharmacists were more likely to use substances (binge alcohol drinking and prescription drug use) than dental and allied health students.25 However, Kenna and Wood (2004) found that student pharmacists had similar rates of alcohol use and lower rates of other drug use compared to nursing students.11 Baldwin and colleagues showed that student pharmacists had lower alcohol consumption in comparison to medical, nursing, and allied health students; however, student pharmacists were more likely to use tobacco when compared to medical, dental, and allied health students.16 Baldwin and colleagues also found that student pharmacists were more likely than other students to use prescription stimulants (amphetamines).16 However, Bossaer and colleagues found no significant difference in rates of prescription stimulant use among pharmacy, medical, and respiratory therapy students.29 Overall, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions from these findings about whether pharmacy students engage in more or less problematic substance use behaviors compared to other health professional students. Furthermore, the methodological issues discussed earlier (eg, inconsistent definitions and measurement of substance use) hinder comparisons across studies.

Current evidence regarding student pharmacists’ problematic substance use calls for the implementation of preventive and treatment strategies in pharmacy schools. A plausible prevention strategy centers on strengthening students pharmacists’ training about SUD and negative outcomes. The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) states that pharmacy schools and colleges are responsible for ensuring that student pharmacists are equipped with the skills and knowledge about substance use and SUDs.36 AACP recommends that all pharmacy schools provide professional SUD-related education in both entry-level and continuing-education programs.36 Substance use can be addressed in coursework and/or cocurricular activities provided by pharmacy schools. Such educational and training programs may help student pharmacists identify signs and symptoms related to problematic substance use among themselves and their colleagues.37

Pharmacy schools also may assist student pharmacists who are at risk of developing or have SUDs by implementing disease-state evaluation, referral programs and interventions that facilitate recovery.36 Student services departments can play a role by assessing and evaluating students they suspect of having a problematic substance use behavior. For example, the Student Assistance Program at Auburn University conducts evaluations of students with problematic substance use.38 Based on evaluation results, students are referred for further evaluation and/or treatment. The Pharmacists Recovery Network website (www.usaprn.org) provides a SUD educational network and a list of available recovery assistance programs by state.39 The role of this network is to provide individuals who seek recovery with confidential assistance and support. Educating students about such programs might increase their willingness to seek help and/or refer colleagues who need help.39 In addtion, general interventions aimed at preventing substance use problems among college students also may be applicable to student pharmacists.40-42 The Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS) is an example of a program that has been found to help general college students with alcohol use problems.43-45 The BASICS was developed to increase students’ motivation to change their drinking habits and to provide them with behavioral skill training on how to control alcohol drinking and how to manage daily stress.44 Such programs could be modified to address factors associated with student pharmacists’ substance use (eg, stress, self-treatment) and implemented to help student pharmacists prevent and/or recover from SUDs.

CONCLUSION

Previous studies suggest that student pharmacists engage in problematic substance use and may be at risk of developing substance use disorders. These findings highlight the need for programs/interventions to address substance use in schools and colleges of pharmacy. Future research should be conducted to gain a better understanding of substance use and SUD developmental processes among student pharmacists. For example, an annual national survey assessing attitudes, motivations, and substance use behaviors among student pharmacists may provide representative data for assessing the change in substance use over time, and help to identify mutable factors contributing to substance use.46 Findings from such research may help pharmacy school administrators and stakeholders prevent substance use issues among students and aid students in need of substance use services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr. Randall L. Tackett, PhD at UGA College of Pharmacy for reviewing the text and providing comments that greatly improved the manuscript. Furthermore, the authors wish to thank Ms. Annelie Klein, Graduate Coordinator Assistant at UGA College of Pharmacy for proofreading this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldisseri MR. Impaired healthcare professional. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):S106–S116. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000252918.87746.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black DW, Grant JE. DSM-5® Guidebook: The Essential Companion to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keen S.DSM criteria for substance use disorders. Salem Press Encyclopedia Of HealthResearch Starters; Ipswich, MA: http://www.salempress.com/press_titles.html?book=22 AccessedSeptember 10, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topics Mental and Substance Use Disorders, Substance Use Disorders. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration http://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/substance-useAccessed November 27, 2016

- 6.Young D. Recovery assistance programs help pharmacists with substance abuse problems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(24):2544–2546. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/60.24.2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dabney DA. Onset of illegal use of mind-altering or potentially addictive prescription drugs among pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2001;41(3):392–400. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)31253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAuliffe WE, Santangelo SL, Gingras J, Rohman M, Sobol A, Magnuson E. Use and abuse of controlled substances by pharmacists and pharmacy students. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1987;44(2):311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollinger RC, Dabney DA. Social factors associated with pharmacists’ unauthorized use of mind-altering prescription medications. J Drug Issues. 2002;32(1):231–264. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenna GA, Wood MD. Prevalence of substance use by pharmacists and other health professionals. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;44(6):684–693. doi: 10.1331/1544345042467281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenna GA, Wood MD. Substance use by pharmacy and nursing practitioners and students in a northeastern state. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(9):921–930. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.9.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merlo LJ, Cummings SM, Cottler LB. Recovering substance-impaired pharmacists’ views regarding occupational risks for addiction. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52(4):480–491. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.10214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bissell L, Haberman PW, Williams RL. Pharmacists recovering from alcohol and other drug addictions: an interview study. Am Pharm. 1989;29(6):19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0160-3450(15)31759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Substance Use Disorders http://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/substance-useAccessed December 15, 2015

- 15.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services AdministrationResults from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National FindingsRockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldwin JN, Scott DM, Agrawal S, et al. Assessment of alcohol and other drug use behaviors in health professions students. Subst Abus. 2006;27(3):27–37. doi: 10.1300/J465v27n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenna GA, Wood MD. Alcohol use by healthcare professionals. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75(1):107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Normark JW, Eckel FM, Pfifferling J-H, Cocolas G. Impairment risk in North Carolina pharmacy students. Am Pharm. 1985;25(6):60–62. doi: 10.1016/s0160-3450(16)32741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noormohamed SE, Ferguson KJ, Baghaie A, Cohen LG. Alcohol use, drug use, and sexual activity among pharmacy students at three institutions. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1998;38(5):609–613. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bidwal MK, Ip EJ, Shah BM, Serino MJ. Stress, drugs, and alcohol use among health care professional students: a focus on prescription stimulants. J Pharm Pract. 2015;28(6):535–542. doi: 10.1177/0897190014544824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volger EJ, McLendon AN, Fuller SH, Herring CT. Prevalence of self-reported nonmedical use of prescription stimulants in North Carolina doctor of pharmacy students. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27(2):158–168. doi: 10.1177/0897190013508139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller CJ, Banahan BF. A comparison of alcohol and illicit drug use between pharmacy students and the general college population. Am J Pharm Educ. 1990;54(1):27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murawski MM, Juergens JP. Analysis of longitudinal pharmacy student alcohol and other drug use survey data. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65(1):20–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lord S, Downs G, Furtaw P, et al. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and stimulants among student pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(4):519–528. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.08027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kriegler KA, Baldwin JN, Scott DM. A survey of alcohol and other drug use behaviors and risk factors in health profession students. J Am Coll Health. 1994;42(6):259–265. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1994.9936357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rascati K, Charupatanapong N, McCormick W. The extent of alcohol and illicit drug use by pharmacy students in Texas. J Pharm Teach. 1993;3(4):67–86. [Google Scholar]

- 27.English C, Rey JA, Schlesselman LS. Prevalence of hazardous alcohol use among pharmacy students at nine US schools of pharmacy. Pharm Pract. 2011;9(3):162–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver W, McGuffey G, Westrick SC, Jungnickel PW, Correia CJ.Alcohol use behaviors among pharmacy students Am J Pharm Educ. 201478(2)Article 30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bossaer JB, Gray JA, Miller SE, Enck G, Gaddipati VC, Enck RE. The use and misuse of prescription stimulants as “cognitive enhancers” by students at one academic health sciences center. Acad Med. 2013;88(7):967–971. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318294fc7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldwin JN, Scott DM, DeSimone EM, II, Forrester JH, Fankhauser MP. Substance use attitudes and behaviors at three pharmacy colleges. Subst Abus. 2011;32(1):27–35. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.540470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szeinbach SL, Banahan BF. Pharmacy students attitudes toward the need for university implemented policies regarding alcohol and illicit drug use. Am J Pharm Educ. 1990;54(2):155–158. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tucker DR, Gurnee MC, Sylvestri MF, Baldwin JN, Roche EB. Psychoactive drug use and impairment markers in pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 1988;52:42–47. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frick LJ, Frick JL, Coffman RE, Dey S.Student stress in a three-year doctor of pharmacy program using a mastery learning educational model Am J Pharm Educ. 201175(4)Article 64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall LL, Allison A, Nykamp D, Lanke S.Perceived stress and quality of life among doctor of pharmacy students Am J Pharm Educ. 200872(6)Article 137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stecker T. Well-being in an academic environment. Med Educ. 2004;38(5):465–478. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2929.2004.01812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jungnickel PW, DeSimone EM, Kissack JC, et al. Report of the AACP special committee on substance abuse and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):S11. doi: 10.5688/aj7410s11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wenthur CJ, Cross BS, Vernon VP, et al. Original research: opinions and experiences of Indiana pharmacists and student pharmacists: the need for addiction and substance abuse education in the United States. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(1):90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Successful Practices in College/School Involvement with Substance Abuse and Chemical Dependency Programs. 2010. Pharmaceutical Education. . http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Documents/Subs%20Abuse%20Final.pdf.

- 39.Broussard C.Pharmacists Recovery Network http://www.usaprn.orgAccessed Aug. 26, 2015

- 40.Larimer ME, Kilmer JR, Lee CM. College student drug prevention: a review of individually oriented prevention strategies. J Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):431–456. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999-2006. Addict Behav. 2007;32(11):2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A Harm Reduction Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terlecki MA, Buckner JD, Larimer ME, Copeland AL. Randomized controlled trial of brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students for heavy-drinking mandated and volunteer undergraduates: 12-month outcomes. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(1):2–16. doi: 10.1037/adb0000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiFulvio GT, Linowski SA, Mazziotti JS, Puleo E. Effectiveness of the brief alcohol and screening intervention for college students (BASICS) program with a mandated population. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(4):269–280. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.599352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dejong W, Larimer ME, Wood MD, Hartman R. NIAAA’s rapid response to college drinking problems initiative: reinforcing the use of evidence-based approaches in college alcohol prevention. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:5–11. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Norton M, Ford H, Al-Shatnawi SF. The development of the student pharmacist chemical health scale (SPCHS) Mental Health Clinician. 2013;3(6):321–326. http://dx.doi.org/10.9740/mhc.n183965 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. National Trends in Drug Use and Related Factors Among American High School Students and Young Adults, 1975-1986. Washington, DC: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG.Monitoring the Future. National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2000. Volume II: College Students and Adults Ages 19-40Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2001. NIH publication No01–4925. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of National FindingsRockville: MD; 2010Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38AHHS Publication No. SMA 10–4586. Findings [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCabe SE, Knight JR, Teter CJ, Wechsler H. Nonmedical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction. 2005;100(1):96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah AA, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Lindstrom RW, Wolf KE. Prevalence of at-risk drinking among a national sample of medical students. Subst Abus. 2009;30(2):141–149. doi: 10.1080/08897070902802067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. Medical use, illicit use and diversion of prescription stimulant medication. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38(1):43–56. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2006.10399827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teter CJ, McCabe SE, LaGrange K, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ. Illicit use of specific prescription stimulants among college students: prevalence, motives, and routes of administration. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(10):1501–1510. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.10.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]