Abstract

Four genes coding for small heat shock proteins (sHsps) were identified in the genome sequence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, one on the circular chromosome (hspC), one on the linear chromosome (hspL), and two on the pAT plasmid (hspAT1 and hspAT2). Induction of sHsps at elevated temperatures was revealed by immunoblot analyses. Primer extension experiments and translational lacZ fusions demonstrated that expression of the pAT-derived genes and hspL is controlled by temperature in a regulon-specific manner. While the sHsp gene on the linear chromosome turned out to be regulated by RpoH (σ32), both copies on pAT were under the control of highly conserved ROSE (named for repression of heat shock gene expression) sequences in their 5′ untranslated region. Secondary structure predictions of the corresponding mRNA strongly suggest that it represses translation at low temperatures by masking the Shine-Dalgarno sequence. The hspC gene was barely expressed (if at all) and not temperature responsive.

The virulence of pathogenic microorganisms is strongly affected by temperature (11, 16, 41). Whereas a temperature of 37°C induces expression of virulence genes in mammalian pathogens, much lower temperatures are typically favorable for the infection process of plant pathogens. Many virulence genes in Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Pseudomonas syringae, and different Erwinia species are induced at temperatures between 18 and 28°C and repressed at higher temperatures (41). Various reasons account for the reduced infectivity of A. tumefaciens at temperatures above 28°C. (i) The signal transduction pathway mediated by the VirAG two-component regulatory system is functional only below this temperature (15). (ii) Assembly of T-pilus components required for DNA transfer to plant cells is compromised (3, 4, 8, 9, 17). (iii) Degradation of a subset of virulence proteins might occur at elevated temperatures (4).

A puzzling observation was recently made during studies on the temperature stability of the A. tumefaciens type IV secretion system, which translocates DNA and protein into plant cells. Concomitant with the accumulation of plant secondary metabolite-induced virulence proteins at low temperatures, small heat shock proteins (sHsps) were induced (see Discussion of reference 4). Synthesis of sHsps was also observed during symbiosis of Sinorhizobium meliloti with the legume Melilotus alba (30), and root exudates of the symbiotic host Alnus glutinosa induced sHsp synthesis in the actinomycete Frankia sp. strain ACN12a-tsr (12), suggesting a functional importance of sHsps during plant-microbe interaction. Generally, sHsps belong to a large and heterogeneous family of molecular chaperones, also called α-crystallin-type heat shock proteins (α-Hsps) (6, 26). As the name indicates, sHsps are small (around 20 kDa) and usually induced under heat stress conditions. The Escherichia coli Ibp proteins (inclusion body binding proteins IbpA and IbpB) were named Ibp, because they were found associated with inclusion bodies derived from massively overproduced recombinant protein (1). It has been established that sHsps exhibit chaperone-like activity (13, 14). They stably bind to unfolded proteins, maintain them in a folding-competent state, and thus prevent formation of large insoluble aggregates (7, 18). In contrast to most other bacteria, rhizobia produce multiple sHsps after heat shock (23). Two distinct classes could be distinguished on the basis of their primary amino acid sequences. Members of both classes have chaperone activity and assemble into large class-specific oligomers (42).

At least three different mechanisms are known to confer temperature regulation to sHsp-encoding genes in bacteria (26). In many organisms, alternative sigma factors, such as RpoH (σ32), induce heat shock gene transcription under stress conditions (46). RheA, a repressor protein, inhibits transcription of Hsp18 in Streptomyces albus (40). Posttranscriptional control by ROSE (named for repression of heat shock gene expression), a conserved sequence in the 5′ untranslated regions (5′-UTRs) of sHsp genes, in rhizobia has been reported (27, 32). The sequence is predicted to fold into a secondary structure that masks the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence at low temperatures (31). Local melting of that structure at higher temperatures liberates the SD sequence and allows translation (5).

Regulation of the heat shock response in A. tumefaciens is only partially understood. The dnaKJ operon, clpB, and several other heat shock genes are under control of RpoH (19, 24, 38). The groESL operon was found to be under dual control of RpoH and the HrcA repressor (24, 39). Analysis of the heat shock proteome by two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis confirmed these results but also raised additional questions, since 32 of 56 heat shock proteins were induced independently of RpoH and HrcA (34). The existence of at least one additional control mechanism was proposed. Our present study on regulation of the four A. tumefaciens sHsps revealed that ROSE-mediated control is one of these mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

E. coli cells were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with ampicillin (AMP) (200 μg/ml), tetracycline (10 μg/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), or spectinomycin (50 μg/ml) where applicable. A. tumefaciens was routinely grown at 30°C in YEB complex medium at 25°C in AB minimal medium with 1% glucose (36).

Plasmid constructions.

Recombinant DNA work was performed by standard protocols (35). Plasmids pAT5277, pAT5278, and pAT5279 (Table 1) were constructed as follows. PCR-generated fragments were digested with SmaI and PstI before they were ligated into pUC18 treated with the same enzymes. The correct nucleotide sequence was confirmed by automated sequencing. Subsequently, the fragments were transferred into pSUP482 to construct in-frame fusions to the lacZ gene. The entire hsp-lacZ fusions were then cloned via the SmaI and XbaI sites into pVS-BADNco. Reporter plasmids were transferred into E. coli via transformation and into A. tumefaciens via electroporation.

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Relevant characteristic(s) or sequencea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | Cloning host | Gibco-BRL |

| E. coli BL21 (λDE3) | Expression host | 43 |

| A. tumefaciens C58 | Wild type | C. Baron |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | Cloning vector, Apr | 33 |

| pSUP482 | Translational lacZ fusion vector, Tcr | 21 |

| pT7-7StrepII | Strep tag vector carrying T7 promoter | This study |

| pVS-BADNco | A. tumefaciens expression vector, Spr Str | 45 |

| pAT5277 | hspC-lacZ fusion in pVS-BADNco | This study |

| pAT5278 | hspAT2-lacZ fusion in pVS-BADNco | This study |

| pAT5279 | hspL-lacZ fusion in pVS-BADNco | This study |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Sig212 | AAACTGCAGATTGAAGACCCGATCGAACC (PE of hspAT1) | |

| Sig213 | AAACCCGGGAGCTCGGCTGAGACAGTCAT (construction of pAT5278) | |

| Sig214 | AAACTGCAGATTGAGCGCCCGATCGAAAC (construction of pAT5278, PE of hspAT2) | |

| Sig215 | AAACCCGGGCGTTTCGATGATGAAATCGAC (construction of pAT5277) | |

| Sig216 | AAACTGCAGATCAAAACCCAGCAAAAGAGG (construction of pAT5277, PE of hspC) | |

| Sig217 | AAACCCGGGGGCTTTTTCAGGAGCCTTTC (construction of pAT5279) | |

| Sig218 | AAACTGCAGCATCGAGAAAAGACGGTCGAA (construction of pAT5279, PE of hspL) | |

| Sig225 | AAAATCAACGTGACGCATGG (PE of hspL) | |

| Sig228 | CAAAAGAGGGTGGGTGAATG (PE of hspC) | |

| ibpA5 | GGCCGGTACCGATGCGTCACGTTGATTTTTCC (construction of plasmid encoding Strep-tagged HspL) | |

| ibpA3 | GGCCCTGCAGTTAGTTGACCTGAGCCGG (construction of plasmid encoding Strep-tagged HspL) | |

| StrepII5 | CATGGCTAGCTGGAGCCACCCGCAGTTCGAAAAAATCGAAGGGCGCGCGGTACC (construction of pT7-7StrepII) | |

| StrepII3 | CATGGGTACCGCGCGCCCTTCGATTTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCAGCTAGC (construction of pT7-7StrepII) |

Introduced restriction sites are underlined. PE, primer extension.

To produce proteins with an N-terminal StrepII tag for affinity purification, pT7-7/Nco (37) was linearized with NcoI, followed by ligation of the two 5′-phosphorylated and annealed oligonucleotides StrepII5 and StrepII3, which encode the tag sequence. The correct orientation of the ligated oligonucleotides in the resulting vector pT7-7StrepII was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Immunoblot analyses and generation of antisera.

Cells from liquid cultures or from plates were washed with 0.9% NaCl prior to use. Protein concentrations were determined with the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts (20 μg of protein) of each extract were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted onto Hybond-C extra nitrocellulose filters (Amersham). Antisera were used in 1/10,000 dilutions. Bound peroxidase-coupled secondary anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G was detected with the Pierce SuperSignal kit.

Rabbit serum against streptavidin-tagged HspL was generated as follows. The hspL gene was PCR amplified from A. tumefaciens C58 chromosomal DNA with oligonucleotides ibpA5 and ibpA3. The fragment was cleaved with Acc65I and PstI and ligated into similarly cleaved pT7-7StrepII. Transformed cells were plated on LB medium supplemented with AMP (50 μg/ml), and the desired clones were identified by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing. The T7 promoter-carrying plasmid was introduced into E. coli strain BL21(λDE3) for protein overproduction. Cells in 800-ml culture (4x 200 ml in 500-ml flasks) in LB medium containing AMP (100 μg/ml) were induced for 4 h at 37°C with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for overproduction of the protein fused to the N-terminal affinity (StrepII) tag (sequence was WSHPQFEK). The overexpressed StrepII tag fusion protein was purified from cell lysates in one step by affinity chromatography on a streptactin Sepharose column (IBA, Göttingen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified protein (700 μg) was lyophilized and injected into rabbits for the generation of a specific antiserum (BioGenes, Berlin, Germany).

RNA isolation and primer extension.

Total RNA was prepared using hot acid phenol as described previously (2). The oligonucleotides used to map the transcription start sites of hspAT1, hspAT2, hspL, and hspC are listed in Table 1.

β-Galactosidase assays.

The β-galactosidase activity in exponentially growing E. coli and A. tumefaciens cells was measured by standard protocols (20).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Four small heat shock genes in A. tumefaciens.

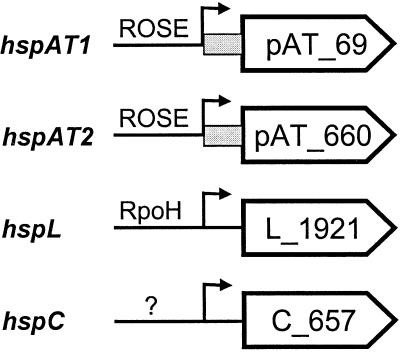

The genome of A. tumefaciens is composed of four replicons, a circular chromosome (2.84 Mb), a linear chromosome (2.07 Mb), the pAT plasmid (0.54 Mb), and the Ti plasmid (0.21 Mb) (10, 44). A search of the complete genome sequences revealed the presence of four genes coding for sHsps on three different replicons. The pAT plasmid encodes two sHsp genes, whereas each chromosome contains one such gene (Fig. 1). The genes were designated hspAT1, hspAT2, hspL, and hspC according to their chromosomal origin.

FIG. 1.

Overview of the four small heat shock genes encoded by A. tumefaciens. The genomic locations (pAT plasmid, linear chromosome, and circular chromosome) are indicated in the gene designations. Potential transcription start sites are represented by arrows. Presumed regulatory mechanisms are listed, and ROSE-type sequences are shown as grey boxes.

Many rhizobia have been shown to produce multiple heat shock genes which often can be divided into two distinct classes, class A and B (23, 26). All four Agrobacterium sHsps clearly fall into class A whose members closely resemble the E. coli Ibp proteins. Pairwise identity between the deduced agrobacterial sHsps and E. coli IbpA ranges from 46 to 55%. Homology to class B proteins is only marginal, e.g., HspAT2 barely shares 20% identical amino acids with Bradyrhizobium japonicum HspC or Methanococcus jannaschii Hsp16.5. Identical residues are restricted to highly conserved motifs, such as the AxxxNGxL motif towards the end of the α-crystallin domain and the IxI motif in the C-terminal extension (data not shown). Agrobacterial sHsps from different replicons exhibit around 45% identity, whereas both proteins derived from the pAT plasmid have 74% of their amino acids in common.

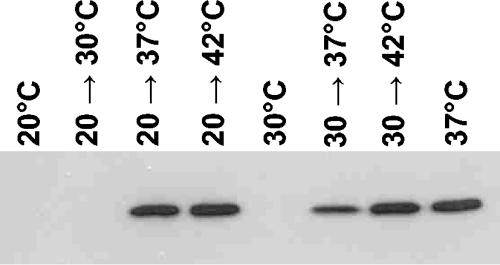

Temperature-dependent production of α-Hsps in A. tumefaciens was monitored by immunoblot analysis using antisera raised against HspL. sHsps were not detected during exponential growth at 20 or 30°C or after a shift from 20 to 30°C (Fig. 2). Continuous growth at 37°C and shifts from 20 to 37 or 42°C triggered sHsp synthesis. In line with the severity of the heat shock, an upshift from 30 to 37°C for 30 min induced much smaller amounts of sHsps than a shift from 30 to 42°C. The results demonstrate that A. tumefaciens precisely records the ambient temperature and adjusts the cellular level of sHsps accordingly.

FIG. 2.

Heat-induced production of sHsps in A. tumefaciens. Cells were grown in YEB medium at the temperatures indicated. For heat treatment, aliquots of the cells were shifted to higher temperatures for 30 min. Harvested cells were subjected to Western blot analysis as described in Materials and Methods using an anti-HspL serum. The detected band migrates at 18 kDa.

By using a proteomic approach, 52 proteins were found to be induced by a temperature upshift in A. tumefaciens (34). Among the proteins identified by MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight) mass spectrometry, only one sHsp was found. However, several other heat-induced spots in the low-molecular-mass range were not identified. They could potentially represent the remaining sHsps. As all four sHsps have similar sequences and molecular masses, only one heat-induced band of 18 kDa was detected by our Western blot analysis. Thus, it remained unclear whether one or more of the four proteins were induced under heat stress conditions. In order to further dissect the mechanisms controlling small heat shock gene expression in A. tumefaciens, all four genes were studied individually.

ROSE-controlled expression of pAT-encoded sHsps.

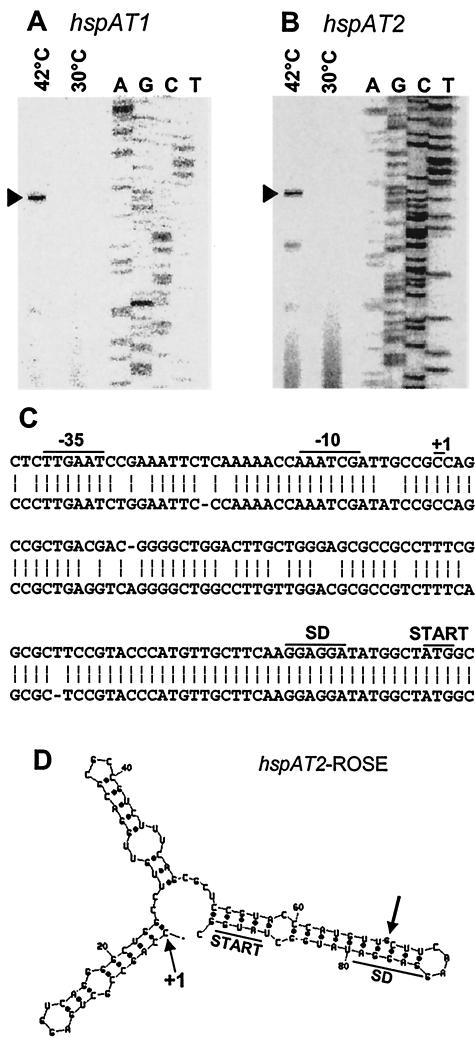

Both hspAT1 and hspAT2 are preceded by a sequence strongly resembling the ROSE motif of many other rhizobial small heat shock genes (31, 32). To assign the precise transcription start sites, primer extension experiments were performed with RNA from normally grown cells and heat-shocked cells. As in B. japonicum, Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234, and other species (29, 32), corresponding transcripts were detected only in RNA preparations from heat-treated A. tumefaciens cells (Fig. 3A and B). The deduced −10 and −35 regions of both hspAT genes are identical and conform to the consensus sequence of a σ70-type promoter. Both approximately 80-nucleotide-long 5′-UTRs downstream of the transcription start sites are highly similar, in particular towards the 3′ end where more than 30 residues including the SD sequences are completely identical (Fig. 3C). Computer-assisted secondary structure predictions of the 5′-UTRs suggest in each case an extended secondary structure resembling ROSE-like elements found in other rhizobia (shown for hspAT2 in Fig. 3D). The characteristic features include the SD sequence and AUG start codon being masked by base pairing as well as a strictly conserved bulged G residue opposite the SD sequence. The corresponding bulged residue in ROSE1 of B. japonicum (G83) was shown to be instrumental in translation initiation at elevated temperatures in vivo (31). Accordingly, thermal melting of an in vitro-synthesized transcript lacking that residue started to melt only at temperatures above 45°C (5).

FIG. 3.

Transcription start site mapping of pAT-encoded small heat shock genes. Primer extension experiments were performed with total RNA from A. tumefaciens grown in YEB medium at 30°C or heat shocked from 30 to 42°C for 30 min. (A) Reverse transcriptase reaction with primer Sig212, and (B) reverse transcriptase reaction with primer Sig214. The corresponding sequencing reactions (AGCT) with pUC18-derived plasmids carrying the hspAT1 and hspAT2 regions, respectively, are shown. The positions of reverse transcripts corresponding to +1 in panel C are indicated by black arrowheads to the left of the gels. (C) Alignment of the deduced promoter regions and ROSE sequences of hspAT1 (top strand) and hspAT2 (bottom strand). Transcription start sites (+1), −10 and −35 regions, Shine-Dalgarno sequences (SD), and translational start sites are indicated. (D) Secondary structure prediction of the hspAT2 ROSE region. The mfold program version 3.1 (http://www.bioinfo.rpi.edu/applications/mfold/old/rna/) was used (47). Nucleotides are numbered starting from the transcription start site (+1). The Shine-Dalgarno sequence and start codon are labeled. A conserved bulged G residue present in all known ROSE elements is indicated by a black arrow.

The absence of transcript at 30°C implies transcriptional control. However, both transcripts originate from a classical housekeeping promoter which should allow significant transcription at low temperatures. Although transcriptional regulation by an unknown mechanism cannot be excluded, the potential RNA structures masking the SD sequence strongly suggests translational control of the pAT-encoded small heat shock genes. In analogy to ROSE-mediated control in other members of the family Rhizobiaceae, we propose that the folded RNA produced at low temperatures is rapidly degraded (31). The melted RNA might either display no RNase recognition sites or might be protected from degradation by the physical presence of ribosomes.

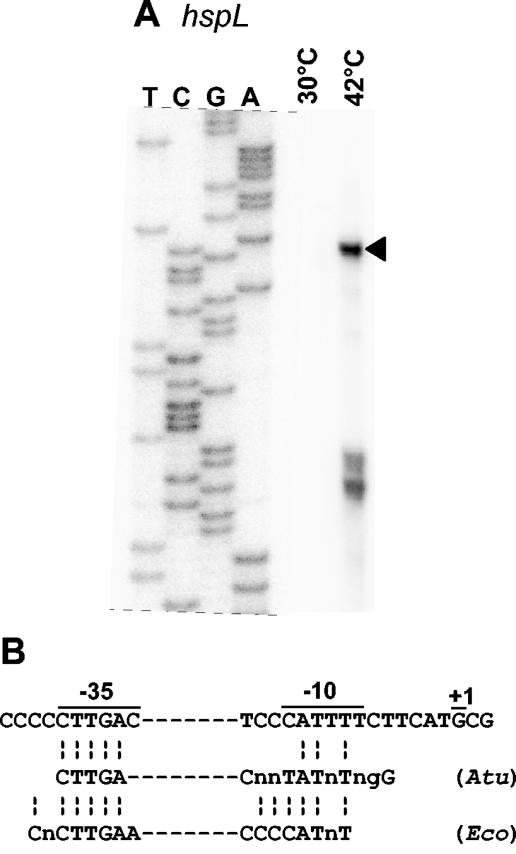

The hspL gene belongs to the RpoH regulon.

Primer extension experiments with oligonucleotides complementary to the 5′ end of hspL revealed transcripts of hspL only under heat shock conditions (Fig. 4A). The deduced transcription start site is preceded by a −10 region and a −35 region with similarity to RpoH-dependent promoters from A. tumefaciens or E. coli (Fig. 4B). The presence of a RpoH-type promoter is consistent with proteome analyses of heat-shocked A. tumefaciens cells (34). Heat induction of a protein named HspD was lost in a ΔrpoH strain. The N-terminal sequence of HspD corresponds to the HspL sequence (Eliora Ron [Tel-Aviv University], personal communication). We suggest renaming HspD and using HspL for its chromosomal location. Interestingly, two different HspL spots were located on two-dimensional protein gels, suggesting covalent modification of the protein (34).

FIG. 4.

Transcription start site mapping of the hspL gene. Primer extension experiments were performed with total RNA from A. tumefaciens grown in YEB medium at 30°C or heat shocked from 30 to 42°C for 30 min. Primers Sig225 (A) and Sig218 (not shown) producing identical results were used. The corresponding sequencing reactions (AGCT) with a pUC18-derived plasmid carrying the hspL region, respectively, are shown. The position of the reverse transcript from which the transcription start site was deduced is indicated by an arrowhead to the right of the gel. (B) The deduced promoter region of hspL is listed and compared with consensus sequences of RpoH-dependent promoters from A. tumefaciens (Atu) and E. coli (Eco) (24).

hspC is not a heat shock gene.

Primer extension experiments with two different oligonucleotides complementary to the 5′ region of hspC did not produce reverse transcripts with RNA preparations from normally grown or heat-shocked A. tumefaciens cells (data not shown), suggesting that hspC is only weakly expressed, if at all.

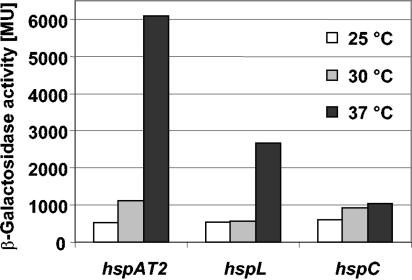

In order to facilitate a comparative analysis of sHsp genes from different replicons, we constructed translational lacZ fusions to hspAT2, hspL, and hspC (Materials and Methods and Table 1). All constructs led to basal expression when A. tumefaciens was grown at 25°C (Fig. 5). Expression of hspAT2-lacZ was elevated during growth at 30°C and induced more than 10-fold at 37°C. The hspL-lacZ fusion was induced fivefold during growth at 37°C. Both results confirm that expression of the ROSE- and RpoH-controlled sHsp genes is temperature regulated. In contrast, the expression of hspC increased only slightly with temperature, indicating again that it is not significantly expressed and not temperature controlled.

FIG. 5.

Temperature-dependent expression of A. tumefaciens small heat shock genes. Cultures were grown to exponential phase in AB medium with glucose at the temperatures indicated before β-galactosidase activity (in Miller units [MU]) was measured.

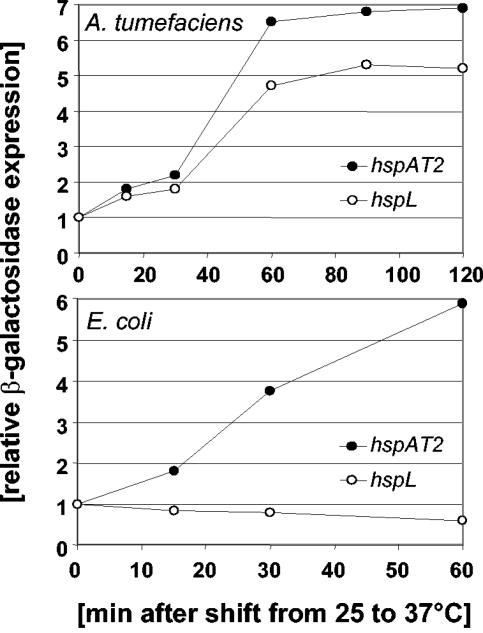

Likewise, expression of the hspC-lacZ fusion was not significantly altered after a shift from 25 to 37°C in A. tumefaciens or E. coli (data not shown). On the other hand, a temperature shift resulted in clear induction of hspAT2 and hspL expression in A. tumefaciens (Fig. 6). An equivalent shift induced only hspAT2 expression in E. coli (Fig. 6), which suggests that ROSE-mediated control is retained in this organism. Similar results were observed with ROSE elements from B. japonicum (5, 31). Although the RpoH-dependent promoter of the hspL gene resembles the consensus sequence for σ32 (Fig. 4B), expression of this gene was not induced by increasing the temperature in E. coli (Fig. 6). It has been observed previously that promoter sequences from α-proteobacteria were not recognized by E. coli RNA polymerase. E. coli σ32-containing RNA polymerase was unable to transcribe the B. japonicum dnaK gene (22), and the σ70-containing holoenzyme of E. coli did not recognize the housekeeping-type hspA-rpoH1 promoter of B. japonicum (31). The A. tumefaciens hspL gene appears to be another example of this phenomenon. On the other hand, the E. coli dnaK promoter was heat activated in A. tumefaciens (38), and the E. coli groESL promoter was transcribed by the B. japonicum RNA polymerase carrying sigma factor RpoH1 or RpoH2 (28). These data suggest that promoter recognition by RNA polymerases from α-proteobacteria is less strict than transcription initiation by the E. coli enzyme.

FIG. 6.

Expression of lacZ fusions to hspAT2 and hspL after a temperature upshift in A. tumefaciens and E. coli. A. tumefaciens cells grown in AB medium with glucose and E. coli grown in LB medium were shifted from 20 to 37°C before β-galactosidase activity was measured at the time points indicated. The activities at timepoint zero were set to 1.

To date, A. tumefaciens is the only known organism in which heat-induced synthesis of sHsps is controlled by two different strategies. The different mechanisms correlate with the chromosomal location, i.e., pAT-encoded genes are regulated by ROSE, and the sHsp gene on the linear chromosome is regulated by RpoH. It is unclear whether both regulons respond to different stimuli. The ROSE sequence presumably measures the ambient temperature, since it was shown be an RNA thermometer (5). The RpoH system most likely responds to the cellular level of unfolded protein, since the activity of RpoH in A. tumefaciens is tightly controlled by the chaperone DnaK (25), which binds to unfolded substrates under stress conditions.

Our results identified the ROSE element in A. tumefaciens as one of the additional heat shock control systems proposed by Rosen et al. (34). However, only two genes, hspAT1 and hspAT2, are regulated by this translation mechanism. A search for additional ROSE-type sequences in the genome of A. tumefaciens demonstrated that no other genes bear such an RNA thermometer. Since 32 of 56 heat shock proteins were shown to be induced independently of RpoH and HrcA (34), induction of a substantial number of proteins still remains to be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hauke Hennecke for providing continuous support, Sandra Penz for providing HspL-specific antiserum, and Eliora Ron for sharing unpublished results on the N-terminal sequence of HspD (HspL).

Work in Christian Baron's laboratory was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant MOP-64300). The work performed in Franz Narberhaus' laboratory was supported by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich, Switzerland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, S. P., J. O. Polazzi, J. K. Gierse, and A. M. Easton. 1992. Two novel heat shock genes encoding proteins produced in response to heterologous protein expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 174:6938-6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babst, M., H. Hennecke, and H. M. Fischer. 1996. Two different mechanisms are involved in the heat-shock regulation of chaperonin gene expression in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol. Microbiol. 19:827-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banta, L. M., J. Bohne, S. D. Lovejoy, and K. Dostal. 1998. Stability of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB10 protein is modulated by growth temperature and periplasmic osmoadaption. J. Bacteriol. 180:6597-6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron, C., N. Domke, M. Beinhofer, and S. Hapfelmeier. 2001. Elevated temperature differentially affects virulence, VirB protein accumulation, and T-pilus formation in different Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Agrobacterium vitis strains. J. Bacteriol. 183:6852-6861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhury, S., C. Ragaz, E. Kreuger, and F. Narberhaus. 2003. Temperature-controlled structural alterations of an RNA thermometer. J. Biol. Chem. 278:47915-47921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Jong, W. W., G. J. Caspers, and J. A. M. Leunissen. 1998. Genealogy of the α-crystallin—small heat-shock protein superfamily. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 22:151-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehrnsperger, M., S. Gräber, M. Gaestel, and J. Buchner. 1997. Binding of non-native protein to Hsp25 during heat shock creates a reservoir of folding intermediates for reactivation. EMBO J. 16:221-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fullner, K. J., J. C. Lara, and E. W. Nester. 1996. Pilus assembly by Agrobacterium T-DNA transfer genes. Science 273:1107-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fullner, K. J., and E. W. Nester. 1996. Temperature affects the T-DNA transfer machinery of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 178:1498-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodner, B., G. Hinkle, S. Gattung, N. Miller, M. Blanchard, B. Qurollo, B. S. Goldman, Y. Cao, M. Askenazi, C. Halling, L. Mullin, K. Houmiel, J. Gordon, M. Vaudin, O. Iartchouk, A. Epp, F. Liu, C. Wollam, M. Allinger, D. Doughty, C. Scott, C. Lappas, B. Markelz, C. Flanagan, C. Crowell, J. Gurson, C. Lomo, C. Sear, G. Strub, C. Cielo, and S. Slater. 2001. Genome sequence of the plant pathogen and biotechnology agent Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2323-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gophna, U., and E. Z. Ron. 2003. Virulence and the heat shock response. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:453-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammad, Y., J. Marechal, B. Cournoyer, P. Normand, and A. M. Domenach. 2001. Modification of the protein expression pattern induced in the nitrogen-fixing actinomycete Frankia sp. strain ACN14a-tsr by root exudates of its symbiotic host Alnus glutinosa and cloning of the sodF gene. Can. J. Microbiol. 47:541-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwitz, J. 1992. α-Crystallin can function as a molecular chaperone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10449-10453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakob, U., M. Gaestel, K. Engel, and J. Buchner. 1993. Small heat shock proteins are molecular chaperones. J. Biol. Chem. 268:1517-1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin, S., Y. N. Song, W. Y. Deng, M. P. Gordon, and E. W. Nester. 1993. The regulatory VirA protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens does not function at elevated temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 175:6830-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konkel, M. E., and K. Tilly. 2000. Temperature-regulated expression of bacterial virulence genes. Microbes Infect. 2:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai, E. M., and C. I. Kado. 1998. Processed VirB2 is the major subunit of the promiscuous pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 180:2711-2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, G. J., A. M. Roseman, H. R. Saibil, and E. Vierling. 1997. A small heat shock protein stably binds heat denatured model substrates and can maintain a substrate in a folding competent state. EMBO J. 16:659-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantis, N. J., and S. C. Winans. 1992. Characterization of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens heat shock response: evidence for a σ32-like sigma factor. J. Bacteriol. 174:991-997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 21.Minder, A. C., H. M. Fischer, H. Hennecke, and F. Narberhaus. 2000. Role of HrcA and CIRCE in the heat shock regulatory network of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J. Bacteriol. 182:14-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minder, A. C., F. Narberhaus, M. Babst, H. Hennecke, and H. M. Fischer. 1997. The dnaKJ operon belongs to the σ32 dependent class of heat shock genes in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol. Gen. Genet. 254:195-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Münchbach, M., A. Nocker, and F. Narberhaus. 1999. Multiple small heat shock proteins in rhizobia. J. Bacteriol. 181:83-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakahigashi, K., E. Z. Ron, H. Yanagi, and T. Yura. 1999. Differential and independent roles of a σ32 homolog (RpoH) and an HrcA repressor in the heat shock response of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 181:7509-7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakahigashi, K., H. Yanagi, and T. Yura. 2001. DnaK chaperone-mediated control of activity of a σ32 homolog (RpoH) plays a major role in the heat shock response of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 183:5302-5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narberhaus, F. 2002. α-Crystallin-type heat shock proteins: socializing minichaperones in the context of a multichaperone network. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:64-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narberhaus, F., R. Käser, A. Nocker, and H. Hennecke. 1998. A novel DNA element that controls bacterial heat shock gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 28:315-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narberhaus, F., M. Kowarik, C. Beck, and H. Hennecke. 1998. Promoter selectivity of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum RpoH transcription factors in vivo and in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 180:2395-2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narberhaus, F., W. Weiglhofer, H. M. Fischer, and H. Hennecke. 1996. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum rpoH1 gene encoding a σ32-like protein is part of a unique heat shock gene cluster together with groESL1 and three small heat shock genes. J. Bacteriol. 178:5337-5346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Natera, S. H. A., N. Guerreiro, and N. A. Djordjevic. 2000. Proteome analysis of differentially displayed proteins as a tool for the investigation of symbiosis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 13:995-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nocker, A., T. Hausherr, S. Balsiger, N. P. Krstulovic, H. Hennecke, and F. Narberhaus. 2001. mRNA-based thermosensor controls expression of rhizobial heat shock genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:4800-4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nocker, A., N. P. Krstulovic, X. Perret, and F. Narberhaus. 2001. ROSE elements occur in disparate rhizobia and are functionally interchangeable between species. Arch. Microbiol. 176:44-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norrander, J., T. Kempe, and J. Messing. 1983. Construction of improved M13 vectors using oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Gene 26:101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen, R., K. Büttner, D. Becher, K. Nakahigashi, T. Yura, M. Hecker, and E. Z. Ron. 2002. Heat shock proteome of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: evidence for new control systems. J. Bacteriol. 184:1772-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Schmidt-Eisenlohr, H., N. Domke, C. Angerer, G. Wanner, P. C. Zambryski, and C. Baron. 1999. Vir proteins stabilize VirB5 and mediate its association with the T pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 181:7485-7492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt-Eisenlohr, H., M. Rittig, S. Preithner, and C. Baron. 2001. Biomonitoring of pJP4-carrying Pseudomonas clororaphis with Trb protein-specific antisera. Environ. Microbiol. 3:720-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Segal, G., and E. Z. Ron. 1995. The dnaKJ operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: transcriptional analysis and evidence for a new heat shock promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:5952-5958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segal, G., and E. Z. Ron. 1996. Heat shock activation of the groESL operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens and the regulatory roles of the inverted repeat. J. Bacteriol. 178:3634-3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Servant, P., C. Grandvalet, and P. Mazodier. 2000. The RheA repressor is the thermosensor of the HSP18 heat shock response of Streptomyces albus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3538-3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smirnova, A., H. Li, H. Weingart, S. Aufhammer, A. Burse, K. Finis, A. Schenk, and M. S. Ullrich. 2001. Thermoregulated expression of virulence factors in plant-associated bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 176:393-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Studer, S., and F. Narberhaus. 2000. Chaperone activity and homo- and hetero-oligomer formation of bacterial small heat shock proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37212-37218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Studier, F. W., A. H. Rosenberg, J. J. Dunn, and J. W. Dubendorff. 1990. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 185:60-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood, D. W., J. C. Setubal, R. Kaul, D. E. Monks, J. P. Kitajima, V. K. Okura, Y. Zhou, L. Chen, G. E. Wood, N. F. Almeida, Jr., L. Woo, Y. Chen, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, P. D. Karp, D. Bovee, Sr., P. Chapman, J. Clendenning, G. Deatherage, W. Gillet, C. Grant, T. Kutyavin, R. Levy, M. J. Li, E. McClelland, A. Palmieri, C. Raymond, G. Rouse, C. Saenphimmachak, Z. Wu, P. Romero, D. Gordon, S. Zhang, H. Yoo, Y. Tao, P. Biddle, M. Jung, W. Krespan, M. Perry, B. Gordon-Kamm, L. Liao, S. Kim, C. Hendrick, Z. Y. Zhao, M. Dolan, F. Chumley, S. V. Tingey, J. F. Tomb, M. P. Gordon, M. V. Olson, and E. W. Nester. 2001. The genome of the natural genetic engineer Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2317-2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeo, H. J., Q. Yuan, M. R. Beck, C. Baron, and G. Waksman. 2003. Structural and functional characterization of the VirB5 protein from the type IV secretion system encoded by the conjugative plasmid pKM101. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15947-15962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yura, T., M. Kanemori, and M. T. Morita. 2000. The heat shock response: regulation and function, p. 3-18. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 47.Zuker, M. 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3406-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]