Abstract

Diphthamide, a posttranslational modification of translation elongation factor 2 that is conserved in all eukaryotes and archaebacteria and is the target of diphtheria toxin, is formed in yeast by the actions of five proteins, Dph1 to -5, and a still unidentified amidating enzyme. Dph2 and Dph5 were previously identified. Here, we report the identification of the remaining three yeast proteins (Dph1, -3, and -4) and show that all five Dph proteins have either functional (Dph1, -2, -3, and -5) or sequence (Dph4) homologs in mammals. We propose a unified nomenclature for these proteins (e.g., HsDph1 to -5 for the human proteins) and their genes based on the yeast nomenclature. We show that Dph1 and Dph2 are homologous in sequence but functionally independent. The human tumor suppressor gene OVCA1, previously identified as homologous to yeast DPH2, is shown to actually be HsDPH1. We show that HsDPH3 is the previously described human diphtheria toxin and Pseudomonas exotoxin A sensitivity required gene 1 and that DPH4 encodes a CSL zinc finger-containing DnaJ-like protein. Other features of these genes are also discussed. The physiological function of diphthamide and the basis of its ubiquity remain a mystery, but evidence is presented that Dph1 to -3 function in vivo as a protein complex in multiple cellular processes.

Diphthamide is a unique posttranslationally modified histidine residue found only in translation elongation factor 2 (eEF-2). It is conserved from archaebacteria to humans and serves as the target for diphtheria toxin (DT) and Pseudomonas exotoxin A (ETA) (9). DT and ETA specifically catalyze the transfer of ADP-ribose from NAD+ to diphthamide on eEF-2 (Fig. 1A), thus inactivating eEF-2, halting cellular protein synthesis, and causing cell death. Although diphthamide has been found in all eukaryotic organisms and archaebacteria, it is not present in eubacteria. Thus, DT and ETA have evolved a specific mechanism for targeting eukaryotic protein-synthetic machinery without inactivating the analogous elongation factor (EF-G) present in the bacterial pathogens that produce them. Despite the fact that this modification was first identified nearly 25 years ago (32), no obvious role for diphthamide has yet been identified in the normal physiology of the eukaryotic cell. In fact a number of mutants have been identified in both yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and CHO cells that fail to make diphthamide, yet these mutants do not exhibit obvious phenotypes (7, 26).

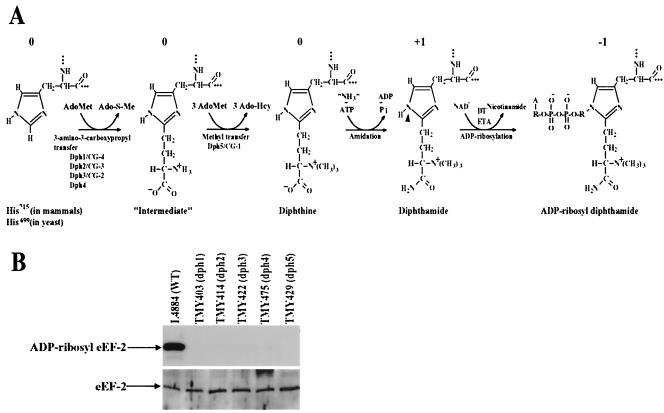

FIG. 1.

DPH1 to DPH5 genes are required for diphthamide biosynthesis. (A) Diphthamide biosynthesis and ADP ribosylation. N-1 (arrowhead) of the histidine imidazole ring of diphthamide is the site for ADP ribosylation by DT and ETA. Ado-S-Me, methylthioadenosine; Ado-Hcy, S-adenosylhomocysteine. In ADP-ribosyl diphthamide, A, adenine moiety; R, ribosyl moiety. The relative net charges of the modified His side chains are indicated above each species. (B) Precise deletions of each of DPH1 to DPH5 genes result in the yeast mutants being completely resistant to ADP ribosylation by DT. (Top) Yeast cell lysates were incubated with [adenylate-32P]NAD and DT at room temperature for 30 min. The reactions were terminated by boiling the lysates in SDS sample buffer, and the samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by autoradiography. (Bottom) Deletions of each of the DPH1 to DPH5 genes do not affect overall expression of eEF-2 protein as evidenced by Western blot analysis using an anti-eEF-2 antibody (a gift of Angus Nairn, Rockefeller University).

The biosynthesis of diphthamide represents one of the most complex posttranslational modifications. The biosynthesis is accomplished by stepwise additions to the His715 (His699 in yeast) residue of eEF-2 (6, 25, 26), beginning with transfer of the 3-amino-3-carboxypropyl group of S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) to the imidazole C-2 of the precursor histidine residue (Fig. 1A). Trimethylation of the resulting amino group follows, using AdoMet as the methyl donor, to produce diphthine. The final step is an ATP-dependent amidation of the carboxyl group, yielding diphthamide. This complex pathway is amenable to genetic analysis, and mutants defective in diphthamide biosynthesis have been isolated in both CHO cells and yeast cells by selection for resistance to the actions of DT and ETA. The previously defined mutations are recessive and have been shown to sort into five complementation groups (Dph1, Dph2, Dph3, Dph4, and Dph5) in yeast (7) and three complementation groups (CG-1, CG-2, and CG-3) in CHO cells (26). Biochemical analyses suggested that the gene products lacking in the yeast dph1, dph2, dph3, and dph4 mutants and the CHO complementation groups CG-2 and CG-3 are involved directly or indirectly in the first step of diphthamide biosynthesis—the transfer of 3-amino-3-carboxypropyl from AdoMet to the imidazole C-2 of the precursor histidine residue in eEF-2—whereas the genes lacking in dph5 and CG-1 act in the trimethylation of the diphthamide intermediate (Fig. 1A) (6, 7, 22, 26). No mutations in the final amidation step were obtained in the previous selections because diphthine can be ADP ribosylated, although slowly, and therefore amidation-deficient mutants would not be resistant to DT (26).

Mattheakis and colleagues identified the S. cerevisiae DPH2 and DPH5 genes by using a genetic-complementation approach. DPH2 encodes a 534-residue protein with no conserved domains that might suggest a function (23). DPH5 encodes a 300-residue AdoMet-dependent methyltransferase (22). Recently, the gene impaired in a CG-2 CHO mutant was shown to encode an 82-residue peptide, and the gene was named DESR1, for DT and ETA sensitivity required gene 1 (19). Its functional homolog in yeast, the Kluyveromyces lactis toxin-insensitive gene 11 (KTI11), was originally identified as a gene regulating the sensitivity of S. cerevisiae to zymocin (11), implicating DESR1/KTI11 in multiple biological processes.

In the work presented below, we report the identification of the remaining three genes, DPH1, DPH3, and DPH4, from yeast and the three genes impaired in the CG-1, CG-3, and CG-4 diphthamide-deficient CHO mutants that are required for diphthamide biosynthesis. We show that all five Dph proteins are highly conserved among eukaryotic species, underscoring the apparent evolutionary importance of the unique diphthamide modification to eEF-2. We propose a unified nomenclature for these proteins (i.e., HsDph1 to -5 for the human proteins) and their genes based on the yeast nomenclature. We show that DPH1, the gene also identified as impaired in a CG-4 CHO mutant, appears to be identical to the recently identified OVCA1 (for ovarian cancer gene 1), a tumor suppressor gene (5) that plays a crucial role in the regulation of cell proliferation, embryonic development, and tumorigenesis. Dph1 and Dph2 are homologous in sequence and associate in vivo but are functionally independent. Other features of the diphthamide biosynthesis genes are also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, media, and genetic methods.

The yeast strains used and constructed in this study are listed in Table 1. Yeast mutants representing each of the five Dph complementation groups (Dph1, Dph2, Dph3, Dph4, and Dph5) defined previously (7) were kindly provided by James W. Bodley (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis). The URA3-marked plasmid pLMY101 encoding the DT F2 fragment (under the transcriptional control of the yeast GAL1 promoter) (22) was a kind gift of R. John Collier (Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass.). Precise deletions of each of the DPH genes were constructed in a W303 genetic background by PCR amplification of a selectable marker flanked with the relevant DPH sequences and transformation into strain L4884 to yield TMY403, TMY414, TMY422, TMY475, and TMY429 (Table 1). Strain 10556-6B is isogenic with this series and was used as a wild-type strain to control for the tryptophan prototrophy associated with the dph1, dph4, and dph5 knockouts.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Dph1/TMY288 | MATadph1-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3Δ1 trp1-289 met2 arg4 | 7 |

| Dph2/TMY289 | MATadph2-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3Δ1 trp1-289 met2 arg4 | 7 |

| Dph3/TMY290 | MATadph3-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3Δ1 trp1-289 met2 arg4 | 7 |

| Dph4/TMY291 | MATadph4-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3Δ1 trp1-289 met2 arg4 | 7 |

| Dph5/TMY292 | MATadph5-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3Δ1 trp1-289 met2 arg4 | 7 |

| L5146 | MATaura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3 trp1Δ63 ade2 lys2Δ201 | Fink collection |

| TMY196 | L5146 carrying pLMY101, a URA3-marked plasmid encoding DT F2 fragment, which is under the transcriptional control of the yeast GAL1 promoter (22) | This study |

| 10560-4A | MATaura3-52 leu2::hisG his3::hisG trp1::hisG | Fink collection |

| TMY203 | 10560-4A carrying pLMY101 | This study |

| 10560-6B | MATα ura3-52 leu2::hisG his3::hisG trp1::hisG | Fink collection |

| TMY204 | 10560-6B carrying pLMY101 | This study |

| 10560-23C | MATα ura3-52 leu2::hisG his3::hisG | Fink collection |

| TMC58-6D | MATadph3-1 ura3-52 leu2 his3 trp1-289, resulting from a cross between 10560-23c and Dph3/TMY290 | This study |

| TMY345 | TMC58-6D carrying pLMY101 | This study |

| L4884 | MATα ura3-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 ade-2 trp1Δ63 can1-100 | Fink collection |

| TMY403 | Same as L4884, but dph1Δ::TRP1 | This study |

| TMY414 | Same as L4884, but dph2Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| TMY422 | Same as L4884, but dph3Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| TMY475 | Same as L4884, but dph4Δ::TRP1 | This study |

| TMY429 | Same as L4884, but dph5Δ::TRP1 | This study |

| 10556-6B | MATα ura3-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 ade-2 can1-100 | Fink collection |

MATa, a mating type; MATα, alpha mating type.

Yeast strains were grown using standard methods (13) in rich medium (yeast-peptone-dextrose or yeast-peptone-dextrose supplemented with 0.3 mM adenine) or synthetic complete (SC) medium with one or more nutrients omitted as indicated (e.g., SC minus Ura) and either glucose or galactose as a carbon source. Solid medium was prepared by adding agar to 2%. Unless otherwise indicated, all incubations were done at 30°C on plates or in shaking flasks.

ADP ribosylation assay.

The assay for ADP ribosylation of eEF-2 in yeast or CHO cell extracts was described previously (19, 22).

CHO cell lines, cell culture, and transfection.

CHO K1 parental cells and their DT-resistant mutants RPE3b (CG-1), RPE33d (CG-3), and RPE22e (CG-3) (25, 26) were kind gifts from Gary Ward (University of Vermont). CHO cell mutant PR303 (CG-4) was isolated by retroviral insertional mutagenesis from its parental CHO WTP4 cells (19). All CHO cells were grown in α minimal essential medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 50 μg of gentamicin/ml, and 25 mM HEPES.

The mouse DPH1, DPH2, and DPH5 cDNA fragments were isolated by reverse transcription-PCR from mouse liver total RNA. The mouse DPH1 cDNA fragment was amplified using the 5′ primer Dph1-5 (AAGTGTACATGGCGGCGCTGGTTGTGTCCGAGACT; the BsrGI site is in boldface, and the start codon is underlined) and a 3′ primer, Dph1-3 (TCATGATCAGGGAGCCGGCGAAGTAGCCTTCT; the antisense of the stop codon is underlined; the BclI site is in boldface). The mouse DPH2 cDNA fragment was amplified using the 5′ primer Dph2-5 (AAGTGTACATGGAGTCTACGTTCAGCAGCCCTGC; the BsrGI site is in boldface, and the start codon is underlined) and a 3′ primer, Dph2-3 (TCATGATCAGCTGCTCCCCTCATCCTCGTAGGC; the antisense of the stop codon is underlined, and the BclI site is in boldface). The mouse DPH5 cDNA fragment was amplified using the 5′ primer Dph5-5 (AAGCGTACGATGCTTTACTTGATCGGCTTGGGCCTGGGA; the BsiWI site is in boldface, and the start codon is underlined) and a 3′ primer, Dph5-3 (TCATGATCAGAGTCCATCAGTACTCTGGGATTC; the antisense of the stop codon is underlined, and the BclI site is in boldface). The amplified cDNA fragments were then digested by BsrGI and BclI in the cases of mouse DPH1 and mouse DPH2 and by BsiWI and BclI for mouse DPH5 and cloned between the BsrGI and BamHI sites of pIRESHgy2B (catalog no. 6939-1; Clontech). This bicistronic mammalian expression vector contains an attenuated version of the internal ribosome entry site of the encephalomyocarditis virus, which allows both the gene of interest and the hygromycin B selection marker to be translated from a single mRNA. The expression plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing and were transfected into CHO cells by using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Life Technologies), and the stably transfected cells were selected by growth in hygromycin B (500 μg/ml) for 2 weeks. The expression plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Cytotoxicity assays.

DT was produced as described previously (4). The CHO cell cytotoxicity assay with MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was performed as described previously (19).

Western blot analysis.

CHO cells grown in 24-well plates were lysed by adding 100 μl of modified RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors/well (19). Portions (20 μl) of the cell lysates were incubated with or without 300 ng of fully nicked DT at room temperature for 30 min and then were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) or native PAGE using 4 to 12% Tris-glycine gradient gels (Novex, San Diego, Calif.). Prior to being loaded, the cell lysates were boiled for 5 min in 1× SDS sample buffer (Novex) for SDS-PAGE or were incubated for 10 min at room temperature in 1× native sample buffer (Novex) for native PAGE. The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes overnight, followed by Western blotting using a goat antibody (catalog no. sc-13004; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.) directed to a linear peptide at the carboxyl terminus of eEF-2.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay.

The amino-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (MYPYDVPDYA)- or Myc epitope (MASMQKLISEEDL)-tagged mouse DPH1, mouse DPH2, and mouse DPH5 cDNA fragments were amplified by using the pairs of 5′-tag-coding primers (with the sequence coding for the tags and the amino termini of the Dph proteins) and 3′ primers listed above. These tagged cDNA fragments were then cloned into the expression plasmid pIRESHgy2B, resulting in the HA- or Myc-tagged Dph protein expression plasmids (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), which were confirmed by sequencing. Combinations of these plasmid constructs (3 μg each), in some cases containing HsDph3-HA (19), were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent into CHO K1 cells grown in T25 flasks. Cell lysates were prepared using modified RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors after 24 h and immunoprecipitated using an agarose-conjugated anti-Myc antibody (catalog no. sc-789AC; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-HA antibody (catalog no. sc-7392; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

RESULTS

Isolation of diphthamide-deficient yeast mutants and cloning of the corresponding genes.

Diphthamide-deficient mutants were selected, based on their resistance to the conditional intracellular expression of the DT F2 fragment, as described previously (22) from pools of cells that were either transposon mutagenized or unmutagenized (spontaneous mutants). Transposon mutants were generated by transformation of a transposon-mutagenized genomic library (3) into strain TMY196 (Table 1), which carries a URA3-marked plasmid, pLMY101 (22), expressing the DT F2 fragment (22). The 75,000 independent transformants obtained were pooled, and a total of 1.1 × 106 CFU was plated on 10 SC plates minus Ura-Leu with galactose as the sole carbon source to induce DT expression. Colonies that arose were designated DTR (DT resistant) and patched to master plates for subsequent analysis. To determine whether these DTR survivors belonged to the five complementation groups previously identified (7), they were crossed with dph1, dph2, dph3, dph4, and dph5 strains (Table 1). If the resultant diploid was able to grow (no complementation) on a galactose plate, then the parent strains were considered to be in the same complementation group. Failure to grow indicated a different complementation group. Through this analysis, 484 recessive mutants were identified, and each could be classified into one of the complementation groups Dph1, Dph2, Dph4, and Dph5 (Table 2), with none identified as dph3 mutants.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of transposon-induced and spontaneous DT-resistant yeast mutants falling in each complementation group

| Complementation group | No. (%) of transposon mutants | No. (%) of spontaneous mutants | Total no. (%) | No. (%) of dph mutants isolated by Chen et al. (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dph1 | 157 (32) | 92 (25) | 249 (29) | 17 (55) |

| Dph2 | 1 (0.2) | 52 (14) | 53 (6) | 9 (29) |

| Dph3 | 0 (0) | 46 (13) | 46 (5) | 1 (3) |

| Dph4 | 134 (28) | 136 (37) | 270 (32) | 3 (10) |

| Dph5 | 192 (40) | 37 (10) | 229 (27) | 1 (3) |

| Total | 484 (100) | 363 (100) | 847 (100) | 31 (100) |

Because DPH2 and DPH5 were identified previously, only dph1 and dph4 strains were further analyzed. Crossing representative transposon-induced clones of the Dph1 and Dph4 complementation groups with wild-type strains resulted in 2:2 segregation, consistent with mutations at single loci. In each case, the LEU2 transposon marker cosegregated with the DTR phenotype. To identify the targeted genes, several transposon insertion sites were sequenced and found to correspond to insertions in open reading frame (ORF) YIL103w in dph1 strains and ORF YJR097w in dph4 strains. The DPH1 and DPH4 gene identities were further confirmed by precisely deleting the YIL103w and YJR097w ORFs using a PCR-mediated deletion approach (1), resulting in deletion strains TMY403 and TMY475 (Table 1). Lysates of these strains had no DT-catalyzed ADP-ribose acceptor activity (Fig. 1B). The properties of these DPH genes and their relationships to mammalian genes from these and later analyses are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Summary of yeast and mammalian genes involved in diphthamide biosynthesis

| Dph protein | Role in diphthamide biosynthesis | Yeast

|

Mammalian

|

% Identity between:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name (ORF) | Protein description and localizationa | Representative mutant strains | Gene name (Unigene identifier) | Protein (mouse) description | CHO CGb | CHO mutants | Yeast and mouse | Mouse and human | ||

| Dph1 | 3-Amino-3-carboxypropyl transfer | DPH1 (YIL103w) | 425 aa; 16% identity to ScDph2; cytoplasm | TMY288, TMY403 | DPH1, OVCA1, Dph2L1, (Mm.298543) | 438 aa; tumor suppressor; 19% identity to MmDph2 | CG-4 | PR303 | 49 | 86 |

| Dph2 | 3-Amino-3-carboxypropyl transfer | DPH2 (YKL191w) | 534 aa; 16% identity to ScDph1; cytoplasm | TMY289, TMY414 | DPH2, Dph2L2 (Hs.324830) | 489 aa; 19% identity to MmDph1 | CG-3 | PRE33d, PRE22e | 22 | 83 |

| Dph3 | 3-Amino-3-carboxypropyl transfer | DPH3, KT111, (YBL071-wA) | 82 aa; CSL zinc finger domain; cytoplasm, nucleus | TMY290, TMY422 | DPH3, DESR1 | 82 aa; CSL zinc finger domain | CG-2 | PIR2D17, PR72c, PR201c | 36 | 96 |

| Dph4 | Unknown | DPH4 (YJR097w) | 172 aa; DnaJ domain, CSL zinc finger domain; cytoplasm, nucleus | TMY291, TMY475 | DPH4, DjC7? | MmDjC7 193aa or 148 aa isoform; DnaJ domain, CSL zinc finger domain | 22 | 83 | ||

| Dph5 | Trimethylation | DPH5 (YLR172c) | 300 aa; diphthine methyltransferase; cytoplasm | TMY292, TMY429 | DPH5 (Dm.2376) | 281 aa; diphthine methyltransferase | CG-1 | RPE3b | 55 | 88 |

In parallel with the transposon mutagenesis approach, spontaneous DT-resistant mutants were selected by plating ∼108 cells of the pLMY101-carrying strains, TMY203 and TMY204 (Table 1), on SC plates minus Ura supplemented with galactose to induce expression of the DT gene. The resulting DTR clones were analyzed as described above. A total of 363 recessive DT-resistant mutants were obtained, and all of them were found to belong to the five known complementation groups (Table 2). In contrast to the transposon-induced mutants, the spontaneous mutants included a number of dph3 mutants (Table 2). To clone the DPH3 gene, TMY345, a dph3 strain harboring pLMY101 (Table 1), was transformed with a yeast genomic library (30) on SC plates minus Ura, using glucose as the carbon source. The transformants were screened by replica plating on SC plates minus Ura, using galactose as the carbon source to induce expression of DT. The two DT-sensitive colonies that were isolated contained overlapping genomic fragments. Subcloning and complementation analysis revealed that the dph3-complementing activity was present on a 2.4-kb SacI-NarI restriction fragment containing the ORF YBL071w-A. Precise deletion of the genomic copy of this gene resulted in strain TMY422 (Table 1), which had no DT-catalyzed ADP-ribose acceptor activity (Fig. 1B).

Identification of the genes required for diphthamide biosynthesis in CHO cells.

DT-resistant CHO mutants were isolated previously by several groups, including our own, so as to identify mechanisms by which ADP-ribosylating toxins damage eukaryotic cells. The first set of such mutants (24-26) were sorted by cell fusion methods into three complementation groups, CG-1 to CG-3. The CHO diphthamide-deficient mutants we isolated fell into these complementation groups (19), with the exception of a mutant designated CHO PR303, which defines an additional complementation group, CG-4, discussed below. We recently identified the gene mutated in a CG-2 mutant as DESR1, the homolog of yeast KTI11 (YBL071w-A) (19). As noted above, dph3 mutants have mutations in YBL071w-A, showing that DPH3 corresponds to the gene mutated in CG-2 (DESR1, referred to as DPH3 hereafter). We also identify below the genes impaired in the CG-1, CG-3, and CG-4 mutants and associate all the CHO and yeast complementation groups, with the results summarized in Table 3.

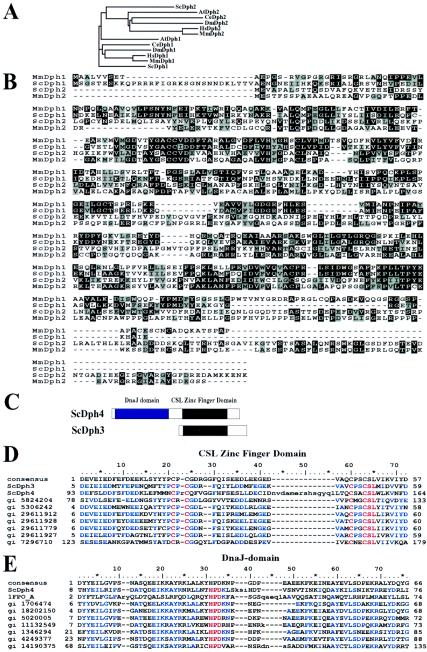

Yeast DPH1 (YIL103w) encodes a 425-residue protein with no obvious structural motifs but with significant amino acid sequence similarity to yeast Dph2 (ScDph2; 16% amino acid identity) (Fig. 2A and B). Despite the sequence similarity, Dph1 and Dph2 are not interchangeable in yeast, as mutations in either DPH1 or DPH2 block diphthamide biosynthesis and there is no apparent cross-complementation. Higher-eukaryotic genomes also contain a pair of DPH1- and DPH2-related genes. Although there is similarity within the pairs of gene products in each species, sequence alignment and clustering reveals that there are two distinct sequence groups—one corresponding to Dph1 and one corresponding to Dph2 (Fig. 2A and B). Sequence similarity within putative Dph1 or Dph2 clusters (e.g., ScDph1 and MmDph1 [mouse Dph1] show 49% identity) is significantly higher than that between the pairs in the same organism (e.g., ScDph1 and ScDph2 show 16% identity) (Fig. 2A and B). Although these relationships are clear in hindsight, the sequence similarity between Dph1 and Dph2 has led to confusing nomenclature so that the human DPH1 gene has been designated DPH2L or DPH2L1 (28). Therefore, for clarity, we have elected to use a consistent naming convention based on the yeast sequences, with alternate identifiers detailed in Table 3. The species is indicated by a two-letter abbreviation: ScDph1, MmDph1, and HsDph1 refer to Dph1 proteins from S. cerevisiae (yeast), Mus musculus (mouse), and Homo sapiens (human), respectively.

FIG.2.

Sequence alignments of Dph proteins. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of Dph1 and Dph2 from different species. At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans. (B) Sequence alignments of yeast and mouse Dph1 and Dph2 proteins. Identical residues are shaded in black, and similar residues are shaded in gray. Dashes represent gaps in the aligned sequences. (C) Schematic representation of domain arrangements of ScDph3 and ScDph4 proteins. (D) The consensus CSL zinc finger domain sequence from the NCBI conserved-domain database aligned with the amino-terminal region of ScDph3 (residues 5 to 59), the carboxyl-terminal region of ScDph4 (residues 93 to 164), and other related proteins. In the alignment, identical residues are in blue and the four cysteine residues and the highly conserved CSL zinc finger motif are in red. (E) The consensus Dna-J sequence from the NCBI conserved-domain database aligned with the N-terminal region of ScDph4 (residues 8 to 76) and other related proteins. In the alignment, identical residues are in blue and the J-domain signature HPD motif is in red.

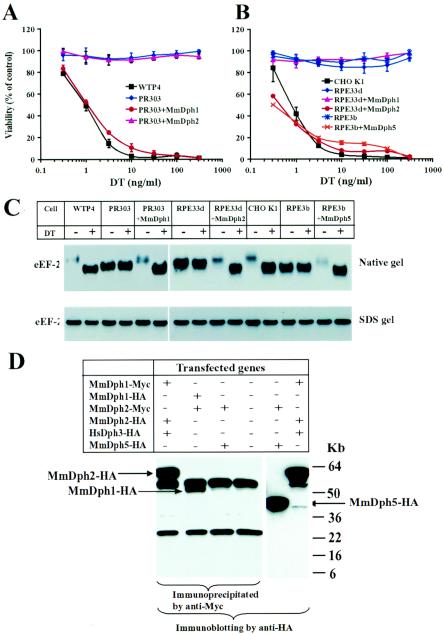

ScDph1 shows 49% identity with both MmDph1 and HsDph1 (human Dph1), whereas ScDph2 shows 22% identity with MmDph2 and HsDph2 (Fig. 2B). The DPH1 genes of mouse and human origins were recently identified as tumor suppressors (OVCA1) (5). To explore the functions of mammalian Dph1 and Dph2 in diphthamide biosynthesis, the mouse cDNA sequences encoding these proteins were cloned into the bicistronic mammalian expression vector pIRESHyg2b. The resulting expression plasmids were then transfected into CG-4 CHO mutant PR303 cells and CG-3 CHO mutant PRE22e and PRE33d cells (Table 4). Stable tranfectants were directly evaluated for sensitivity to DT, and some were expanded as individual clones for further analysis. The majority of the colonies arising from PR303 cells transfected with MmDPH1 and the majority of the colonies from RPE22e and RPE33d cells transfected with MmDPH2 regained the parental sensitivity to DT (Table 4). In contrast, PR303 cells transfected with MmDPH2, and RPE22e and RPE33d cells transfected with MmDPH1, remained toxin resistant (Table 4). Furthermore, the representative individually expanded clones of PR303 cells transfected with MmDPH1 and REP33d cells transfected with MmDPH2 were fully sensitive to DT, just like their parental CHO WTP4 and CHO K1 cells (Fig. 3A and B). These results demonstrated that DPH1 and DPH2 are essential for diphthamide biosynthesis in mammals and also revealed that they are the genes impaired in the CG-4 and CG-3 CHO mutants, respectively. In agreement with the results from yeast, we showed that although MmDph1 and MmDph2 show 19% identity, they are functionally distinct and thus must perform different biochemical functions in diphthamide biosynthesis.

TABLE 4.

Complementation of DT-resistant phenotype of CHO diphthamide-deficient CHO mutants by corresponding DPH genesa

| Cell | Recessive CG | Gene transfected with | Hygr clones (DTs/total) | Cell source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHO RPE3b | CG-1 | MmDph5 | 47/48 | 25 |

| CHO PRE22e | CG-3 | MmDph1 | 0/28 | 25 |

| MmDph2 | 40/44 | |||

| CHO PRE33d | CG-3 | MmDph1 | 0/29 | 25 |

| MmDph2 | 35/43 | |||

| MmDph2-HA | 19/20 | |||

| MmDph2-Myc | 13/14 | |||

| CHO PR303 | CG-4 | MmDph1 | 40/59 | Leppla collection |

| MmDph2 | 0/50 | |||

| MmDph1-HA | 18/23 | |||

| MmDph1-Myc | 20/26 |

Following transfection with the genes indicated, hygromycin-resistant colonies of CHO cells were established by growth for 2 weeks in hygromycin B (500 μg/ml). The cell colonies were marked on the bottom of the dish and then treated with DT (300 ng/ml) for 48 h. The number of toxin-sensitive (i.e., dead) cells versus the total number tested were determined by microscopic observation. Hygr, hygromycin resistant; DTs, DT sensitive; CG, complementation group.

FIG. 3.

Complementation of the diphthamide-deficient CHO mutant cells by transfection with the respective mouse DPH genes. (A) Expression of MmDph1 in CG-4 PR303 cells complements their DT-resistant phenotype. Representative purified clones of PR303 cells transfected with mouse DPH1 or mouse DPH2 were incubated with various concentrations of DT for 48 h, and MTT was added to determine cell viability. Optical density readings were normalized to values for cells that received no toxin to calculate percent viability. (B) Expression of MmDph2 in CG-3 RPE33d cells and MmDph5 in CG-1 RPE3b cells complements their DT-resistant phenotypes. Cytotoxicity of DT to representative clones of RPE33d cells transfected with mouse DPH1 or mouse DPH2 and to a representative clone of RPE3b cells transfected with mouse DPH5 were determined as in panel A. (C) The CHO cell lysates were incubated with or without DT at room temperature for 30 min and then analyzed by either native PAGE (top) or SDS-PAGE (bottom), followed by Western blotting using an antibody against a linear peptide of the carboxyl terminus of eEF-2. +, present; −, absent. (D) Dph1 and Dph2 can physically interact in vivo. Combinations of HA- or Myc-tagged MmDph1, MmDph2, HsDph3, and MmDph5 expression plasmids as indicated were transiently transfected into CHO K1 cells for 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated using an agarose-conjugated anti-Myc antibody, followed by Western blotting using an anti-HA antibody. Expression of MmDph5-HA in MmDph2-Myc- and MmDph5-HA-transfected cells was evidenced by direct Western blot analysis of the cell lysate using the anti-HA antibody. The two bands common in lanes 1 to 4 are to the heavy and light immunoglobulin G chains.

CHO RPE3b is a CG-1 diphthamide-deficient CHO mutant that was shown to be defective in AdoMet-dependent diphthine methyltransferase activity (26), the same activity lacking in yeast dph5 strains (7, 22). Dph5 proteins are highly evolutionarily conserved, with the human and mouse sequences (GenBank accession numbers NP_057042 and BAB26968, respectively) showing 50 and 55% identity, respectively, with the yeast protein. To determine the role of mammalian Dph5 in diphthamide biosynthesis, the MmDPH5 cDNA was isolated and expressed in CHO RPE3b using the same approach described above. The results showed that MmDPH5 could reverse the toxin-resistant phenotype of RPE3b cells (Table 4 and Fig. 3B), demonstrating the conserved function of mammalian Dph5 in the trimethylation step of diphthamide biosynthesis and confirming that the gene impaired in CG-1 diphthamide-deficient CHO mutant is DPH5.

Identification of diphthamide biosynthetic intermediates in CHO mutants.

DT inactivates eEF-2 by catalyzing the covalent attachment of the ADP-ribose moiety (containing two negatively charged phosphate groups) of NAD+ to the N-1 position of the histidine imidazole ring of diphthamide (Fig. 1A). Therefore, the ADP-ribosylated eEF-2 has two added negative charges. The increased negative charge of the modified eEF-2 causes it to migrate faster than the non-ADP-ribosylated eEF-2 during gel electrophoresis under nondenaturing conditions (Fig. 3C). No differences were seen on a denaturing SDS gel (Fig. 3C). This analysis further confirmed that eEF-2 from parental CHO K1 and CHO WTP4 cells could be efficiently ADP ribosylated whereas that from the RPE3b (CG-1; Dph5), RPE33d (CG-3; Dph2), and PR303 (CG-4; Dph1) CHO mutant cells could not (Fig. 3C). The eEF-2 from Dph1- and Dph2-deficient cells migrated on the native gels at a rate intermediate between those of the ADP-ribosylated and non-ADP-ribosylated forms of eEF-2 from the parental cells (Fig. 3C), consistent with the expected net charges on the diphthamide side chains of the various species at neutral pH (Fig. 1A): 0 for His precursor, “intermediate,” and diphthine; +1 for diphthamide; and −1 for ADP-ribosyl-diphthamide. In addition, transfection of the respective cDNAs corresponding to the mutated genes completely restored the normal migration rate of the eEF-2 proteins and made them sensitive to the DT-catalyzed change in mobility (Fig. 3C). Surprisingly, the eEF-2 from CHO RPE3b (Dph5; CG-1) cells comigrated with the ADP-ribosylated form of eEF-2 from wild-type CHO cells (Fig. 3C). As expected, transfection of mouse DPH5 into RPE3b cells made eEF-2 capable of ADP ribosylation, as evidenced by a mobility shift. However, both the ADP-ribosylated and non-ADP-ribosylated forms of eEF-2 migrated faster than the corresponding species from wild-type cells (Fig. 3C). This is most easily explained as due to an unrecognized amino acid substitution in the eEF-2 structural gene that adds a net negative charge.

An interesting observation relevant to the role of diphthamide was that both the nonnative forms of eEF-2, i.e., the mutant, diphthamide-deficient eEF-2 from CG-1, CG-3, and CG-4 and the ADP-ribosylated eEF-2 from wild-type CHO cells, were more reactive with the antibody used in Western blotting, an antibody directed to a peptide sequence at the carboxyl erminus of eEF-2 (Fig. 3C). This was observed with blots from native but not SDS gels, suggesting that the greater reactivity was due to a conformational difference. One possible interpretation is that a conformational change occurs when eEF-2 is ADP ribosylated and that the diphthamide-deficient eEF-2 has a structure that more closely resembles the ADP-ribosylated form rather than the native eEF-2.

Dph1 and Dph2 interact in vivo.

The facts that at least three gene products are involved in the first step of diphthamide biosynthesis (Fig. 1A) and that one of them (Dph3) contains only 82 amino acids led us to suggest that these proteins form a catalytic complex (19). To test whether the proteins interact, vectors were constructed to express MmDph1, MmDph2, MmDph5, and HsDph3 with HA or Myc tags at their amino termini. The tagged proteins were each shown to be functional by demonstrating their abilities to complement the respective mutant cells (Table 4) (19). Various combinations of the constructs were transiently transfected into CHO K1 cells, followed by immunoprecipitation of the cell lysates with an agarose-conjugated anti-Myc antibody and immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. The results showed that MmDph2 could be specifically coimmunoprecipitated with MmDph1 and vice versa (Fig. 3D). In contrast, MmDph5 could not be coimmunoprecipitated with MmDph2, although MmDph5 was well expressed in the cell lysate (Fig. 3D). Experiments with yeast suggested that Dph3 interacts with Dph1 and Dph2 (10). However, we could not observe potential HsDph3 interactions in these experiments because HsDph3-HA was not expressed at detectable levels (Fig. 3D).

Supporting the structural and functional similarities of diphthamide biosynthesis in lower and higher eukaryotes, ScDph1 and ScDph2 were also shown to interact in yeast. ScDph1 and ScDph2 in vivo coassociation was demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation experiments like those described above, as well as by two-hybrid analysis. Based on analysis of multiple DPH2 clones identified from the two-hybrid library, the Dph1-interacting region of Dph2 was localized to residues 50 to 396 (of 534 total) (data not shown). Based on these data, it is likely that Dph1 and Dph2 function in yeast and mammals as a heterodimer or multimer.

DISCUSSION

Mutations affecting the biosynthesis of diphthamide were selected on the basis of resistance to DT that was expressed intracellularly in yeast or added exogenously to cultured mammalian cells. To identify all the genes required for diphthamide biosynthesis, we isolated 847 DT-resistant yeast mutants using both spontaneous and transposon-based mutagenesis approaches. All these mutants fell into the same five complementation groups defined previously by Chen et al. using only 31 DT-resistant mutants (Table 2) (7). The scale of the analysis and the frequency of the mutants strongly suggest that the five loci defined by DPH1- to -5 encode all the proteins required for the first and second steps of diphthamide biosynthesis (Fig. 1A). The DPH2 and DPH5 genes have been characterized previously. In this work, the other three yeast genes, DPH1, DPH3, and DPH4, were identified. We also identified the mammalian DPH homologues in diphthamide-deficient CHO mutants of three complementation groups, CG-1 (dph5), CG-3 (dph2), and CG-4 (dph1). Our previous work identified the gene altered in CHO CG-2 (dph3). All these DPH genes have clear homologues in many organisms and likely function in similar manners, as demonstrated in yeast and CHO cells in this study. The DPH genes in yeast and mammalian cells are summarized in Table 3 and discussed below.

Dph1.

We identified ORF YIL103w as the gene mutated in yeast dph1 mutants. This ORF encodes a 425-residue polypeptide having 49% identity with mouse Dph1 that we were able to show specifically complements the diphthamide biosynthetic defect in CHO CG-4 cells. While this is the first demonstration that DPH1 is required for diphthamide modification in higher eukaryotes, the mouse and human DPH1 genes were previously identified and characterized as OVCA1 (31) and DPH2L1 (28) for very different reasons. Intriguingly, DPH1 of mouse and human origins has been recently identified as a tumor suppressor gene. Human DPH1 is located in a highly conserved region on chromosome 17p13.3, which shows frequent loss of heterozygosity (deletion of one allele) in ovarian and breast carcinomas (2, 28, 29, 31). Western blot analysis of extracts prepared from ovarian and breast cancer cells revealed reduced expression of HsDph1 compared with that from normal epithelial cells from these tissues (2), suggesting that haploinsufficiency of this gene accounts for tumorigenesis. Forced overexpression of human DPH1 caused suppression of cell proliferation and colony formation by ovarian cancer cell lines (2). Furthermore, knockout of one allele of DPH1 in mice leads to increased tumor development, whereas loss of both alleles results in embryonic lethality (5). It appears probable that the effects of MmDph1 deficiency on cell proliferation, embryonic development, and tumorigenesis result from the decrease in, or absence of, diphthamide. The generation of mice lacking other genes in the diphthamide biosynthesis pathway will help to clarify this issue.

Dph2.

The yeast DPH2 gene encodes a 534-residue polypeptide (23) with modest similarity to Dph1 (16% identity). ScDph2 is 22% identical to the predicted product encoded by mouse DPH2, which we showed complements the diphthamide biosynthetic defect of the CHO CG-3 mutants. This result unequivocally establishes that Dph2 has a role in diphthamide biosynthesis in higher eukaryotes and also links Dph2 to CG-3. We showed that Dph1 and Dph2 physically interact in vivo in both yeast and mammalian cells. This suggests that these proteins function as a heterodimer or part of heteromultimeric complex. Despite their primary structural similarity, mutation in either DPH1 or DPH2 completely blocks diphthamide formation in both yeast and CHO cells, demonstrating that the two proteins are functionally independent in diphthamide biosynthesis. Recently, these two proteins were shown in a global analysis of protein localization to be in the cytoplasm (14), where diphthamide modification of eEF-2 is expected to occur.

Dph3.

We identified ORF YBL071w-A as the gene mutated in yeast dph3 mutants. Our previous study had identified DESR1 as the gene mutated in the CHO CG-2 mutant cells and had shown that the yeast homologue ORF YBL071w-A is required for diphthamide biosynthesis in yeast (19). The new result associates Dph3 with DESR1. HsDph3 and ScDph3 are small proteins of only 82 residues which possess a high percentage of negatively charged residues. The sequences of Dph3 from various species are highly conserved in residues 1 to 60 (Fig. 2D) but differ at the carboxyl termini (19). A search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) conserved domain database (20) identified the conserved amino-terminal region as a typical CSL zinc finger domain (this domain is named after the conserved three-residue motif containing the final cysteine) (Fig. 2C and D). The four cysteines in CSL domains are thought to chelate zinc, suggesting that the function of Dph3 and its homologues may depend on their zinc-binding abilities. Sequence analysis of the dph3-1 allele in the original dph3 strain isolated by Chen et al. (7) revealed a G-to-A mutation which would result in the substitution of a tyrosine for the cysteine in the CSL motif of the protein (Fig. 2D and data not shown). This result shows that the CSL zinc motif is crucial to the function of Dph3. The global localization analysis mentioned above showed that Dph3 localizes in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (14).

Yeast DPH3 has also been characterized as KTI11—a gene conferring sensitivity to zymocin, a toxin secreted by the dairy yeast K. lactis (11, 19). Using tandem affinity purification analysis, a recent study showed that the Kti11 protein associates with Dph1, Dph2, and eEF-2 and also with the subunits of the yeast transcriptional Elongator core complex, Elp1, Elp2, and Elp3, that are required for zymocin sensitivity (10). This raised the possibility that the Elongator complex might be involved in diphthamide biosynthesis. Indeed, dph1 and dph2 mutants are moderately resistant to zymocin (10). However, although there does appear to be a link between diphthamide biosynthesis and the Elongator complex, it is not reciprocal, as we demonstrated that elp1, elp2, and elp3 yeast mutants are not defective in diphthamide biosynthesis and thus are sensitive to DT treatment (data not shown).

The association of Dph3 with Dph1 and Dph2 mentioned above suggests the existence of a catalytic protein complex, as was implied by the participation of three genes in the first step of diphthamide synthesis. Interestingly, eEF-2 also copurified with the Dph1, Dph2, and Dph3 complex, along with two ribosomal proteins (10). However, the same tandem affinity purification analysis did not detect Dph4 as a Dph3 interactor, suggesting that Dph4 may function separately or indirectly in diphthamide biosynthesis (discussed further below).

Dph3 is likely to play multiple roles in cellular physiology. Yeast mutants lacking DPH1, DPH2, DPH4, or DPH5 exhibit relatively subtle physiological effects and are largely indistinguishable from wild-type controls (with the exception of resistance to DT) (T. Milne and G. R. Fink, unpublished data). However, in contrast, dph3 mutants have pleiotropic growth defects, including slow growth and drug and temperature hypersensitivity, in addition to DT resistance (11; Milne and Fink, unpublished).

Dph4.

We identified DPH4 as ORF YJR097w, encoding a 172-residue DnaJ-like protein. This DPH gene is the only one of the five for which no corresponding CHO mutant has been obtained. An NCBI conserved-domain database search demonstrated that the first half of the ScDph4 protein (residues 8 to 76) is a typical J domain (Fig. 2C and E) that contains the J-domain signature HPD motif (27). Over 100 DnaJ proteins have been identified (12). The roles most clearly defined thus far for DnaJ-like proteins are as cochaperones aiding HSP70 proteins in the folding of the newly synthesized proteins (12). Therefore, we assume that Dph4 may function in diphthamide biosynthesis by ensuring the proper folding of one or more of the other Dph proteins. Another interesting feature of the Dph4 structure is that the second half of the protein (residues 93 to 164) consists of a typical CSL zinc finger domain, which aligns well with that of Dph3 (Fig. 2D), suggesting that the zinc-binding ability could be essential to its function. The presence of a CSL motif differentiates Dph4 from many other DnaJ-like proteins and may also be indicative of a specialized role. Although we did not directly identify any mammalian homologs of DPH4 in our genetic screens, searching of the GenBank databases showed that the highly conserved 193-residue mouse DnaJ-like protein, MmDjC7 (17), and its 148-residue splicing isoform are probable Dph4 homologs (Table 3). Both have the same domain arrangement as ScDph4—an amino-terminal DnaJ domain followed by a carboxyl-terminal CSL zinc finger domain (20). Interestingly, MmDjC7 has been shown to be ubiquitously expressed and to function as a cochaperone in stimulation of the ATPase activities of several HSP70 proteins, including BiP, Hsc70, and DnaK (17). Like ScDph3, ScDph4 was shown in yeast to localize in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (14).

Dph5.

Yeast DPH5 was previously identified as ORF YLR172c, encoding a 300-residue AdoMet-dependent methyltransferase (22). Dph5 acts in the second biosynthetic step, trimethylation of the diphthamide intermediate to produce diphthine, the step impaired in CHO CG-1 mutants. As expected, ScDph5 is localized in the yeast cytoplasm (14). ScDph5 is highly homologous with its mammalian homologue; ScDph5 shows 55 and 50% identity with MmDph5 and HsDph5, respectively. Dph5 proteins from different species are members of a large family of methyltransferases, but there is no evidence of functional redundancy for diphthamide biosynthesis in either yeast or CHO cells. As expected, MmDph5 can restore the DT-resistant phenotypic change of the CG-1 diphthamide-deficient CHO mutant RPE3b (Table 4), a well-characterized CHO mutant impaired in the trimethylation step of diphthamide biosynthesis, confirming the link of Dph5 to CG-1.

Biosynthesis and role of diphthamide.

The work described here provides a complete description of the five gene products that are required for the biosynthesis of diphthamide. With this information in hand, it is now possible to design structural and biochemical analyses to elucidate the role of each protein in the synthetic process. It appears probable that Dph1, Dph2, and Dph3 form a multimeric complex that catalyzes the transfer of the four-carbon chain onto the eEF-2 His699 side chain. The Dph4 protein may play a role in assembling this complex. The inability to get in vitro complementation by mixing cell lysates of the CHO mutants of CG-2 and CG-3 (26) suggests that any multimeric complex is not readily dissociable, as might be expected if Dph4 acts as an assembly chaperone. It is interesting that the trimethylation of diphthine requires Dph5 and cannot be performed by the many other methylases in mammalian cells. It remains to be determined whether Dph5 catalyzes the transfer of all three methyl groups or only some, with the others added by a less specific methyltransferase.

Although diphthamide is the molecular target for DT and ETA, its biological significance remains elusive. The evolutionary conservation of the complex diphthamide biosynthesis pathway throughout eukaryotes implies a key biological role of diphthamide. This role could be either structural or regulatory. In support of a structural role, systematic mutagenesis of eEF-2 His699 to each of the remaining 19 amino acids resulted in non-ADP-ribosylatable eEF-2 variants that were either inactive (6 of 19) or temperature sensitive for growth (13 of 19) (16). The six nonfunctional alleles underscore the key function of this residue in eEF-2, while the temperature-sensitive alleles suggest that diphthamide may play a role in overall eEF-2 structure or stability. In fact, we observed that the non-diphthamide-modified form of eEF-2 in various CHO dph mutants was bound more readily by anti-eEF-2 antisera than the diphthamide-modified form (Fig. 3C). It is known that eEF-2 undergoes conformational changes during its action on the ribosome (15), so alterations that affect its flexibility could have large effects on its function.

Alternatively, diphthamide may serve as the site of a regulatory modification of eEF-2. Mono-ADP-ribosylation is commonly used in bacterial systems for posttranslational regulation (21). There have been suggestions of similar regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotic systems (8). In fact, the existence of a cellular ADP ribosyltransferase with the same mechanism of action as DT has been reported (18). Furthermore, the discovery in this work that DPH1 is a recently characterized tumor suppressor gene (5) suggests a potential role for diphthamide in the control of cell growth and tumorigenesis.

In this study, we cloned and characterized three previously unidentified DPH genes and the genes impaired in CG-1, CG-3, and CG-4 CHO mutants. Further biochemical and in vivo targeting analyses of these genes will help to define their precise roles in diphthamide biosynthesis and elucidate the mysterious role of diphthamide in cellular physiology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank James W. Bodley for generously providing the original set of the yeast strains of the five Dph complementation groups, R. John Collier for the generous gift of the DT F2 fragment expression plasmid pLMY101, Angus Nairn for the generous gift of an anti-eEF-2 antibody, and Raffael Schaffrath for advice and for providing yeast strains defective in the transcriptional Elongator complex. We especially appreciate the valuable role of Gary Ward in preserving and providing the valuable set of CHO cell mutants originally developed by Thomas and Joan Moehring.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baudin, A., O. Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, A. Denouel, F. Lacroute, and C. Cullin. 1993. A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:3329-3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruening, W., A. H. Prowse, D. C. Schultz, M. Holgado-Madruga, A. Wong, and A. K. Godwin. 1999. Expression of OVCA1, a candidate tumor suppressor, is reduced in tumors and inhibits growth of ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 59:4973-4983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns, N., B. Grimwade, P. B. Ross-Macdonald, E. Y. Choi, K. Finberg, G. S. Roeder, and M. Snyder. 1994. Large-scale analysis of gene expression, protein localization, and gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 8:1087-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll, S. F., J. T. Barbieri, and R. J. Collier. 1988. Diphtheria toxin: purification and properties. Methods Enzymol. 165:68-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, C. M., and R. R. Behringer. 2004. Ovca1 regulates cell proliferation, embryonic development, and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 18:320-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, J. Y., and J. W. Bodley. 1988. Biosynthesis of diphthamide in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Partial purification and characterization of a specific S-adenosylmethionine:elongation factor 2 methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 263:11692-11696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, J. Y., J. W. Bodley, and D. M. Livingston. 1985. Diphtheria toxin-resistant mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5:3357-3360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corda, D., and M. Di Girolamo. 2003. Functional aspects of protein mono-ADP-ribosylation. EMBO J. 22:1953-1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunlop, P. C., and J. W. Bodley. 1983. Biosynthetic labeling of diphthamide in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 258:4754-4758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fichtner, L., D. Jablonowski, A. Schierhorn, H. K. Kitamoto, M. J. Stark, and R. Schaffrath. 2003. Elongator's toxin-target (TOT) function is nuclear localization sequence dependent and suppressed by post-translational modification. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1297-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fichtner, L., and R. Schaffrath. 2002. KTI11 and KTI13, Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes controlling sensitivity to G1 arrest induced by Kluyveromyces lactis zymocin. Mol. Microbiol. 44:865-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink, A. L. 1999. Chaperone-mediated protein folding. Physiol. Rev. 79:425-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guthrie, C., and G. R. Fink. 1991. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology, p. 1-933. In C. Guthrie and G. R. Fink (ed.), Methods in enzymology. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif. [PubMed]

- 14.Huh, W. K., J. V. Falvo, L. C. Gerke, A. S. Carroll, R. W. Howson, J. S. Weissman, and E. K. O'Shea. 2003. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425:686-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorgensen, R., P. A. Ortiz, A. Carr-Schmid, P. Nissen, T. G. Kinzy, and G. R. Andersen. 2003. Two crystal structures demonstrate large conformational changes in the eukaryotic ribosomal translocase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:379-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimata, Y., and K. Kohno. 1994. Elongation factor 2 mutants deficient in diphthamide formation show temperature-sensitive cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 269:13497-13501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroczynska, B., and S. Y. Blond. 2001. Cloning and characterization of a new soluble murine J-domain protein that stimulates BiP, Hsc70 and DnaK ATPase activity with different efficiencies. Gene 273:267-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, H., and W. J. Iglewski. 1984. Cellular ADP-ribosyltransferase with the same mechanism of action as diphtheria toxin and Pseudomonas toxin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:2703-2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, S., and S. H. Leppla. 2003. Retroviral insertional mutagenesis identifies a small protein required for synthesis of diphthamide, the target of bacterial ADP-ribosylating toxins. Mol. Cell 12:603-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchler-Bauer, A., J. B. Anderson, C. DeWeese-Scott, N. D. Fedorova, L. Y. Geer, S. He, D. I. Hurwitz, J. D. Jackson, A. R. Jacobs, C. J. Lanczycki, C. A. Liebert, C. Liu, T. Madej, G. H. Marchler, R. Mazumder, A. N. Nikolskaya, A. R. Panchenko, B. S. Rao, B. A. Shoemaker, V. Simonyan, J. S. Song, P. A. Thiessen, S. Vasudevan, Y. Wang, R. A. Yamashita, J. J. Yin, and S. H. Bryant. 2003. CDD: a curated Entrez database of conserved domain alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:383-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masepohl, B., T. Drepper, A. Paschen, S. Gross, A. Pawlowski, K. Raabe, K. U. Riedel, and W. Klipp. 2002. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in the phototrophic purple bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:243-248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mattheakis, L. C., W. H. Shen, and R. J. Collier. 1992. DPH5, a methyltransferase gene required for diphthamide biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:4026-4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattheakis, L. C., F. Sor, and R. J. Collier. 1993. Diphthamide synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: structure of the DPH2 gene. Gene 132:149-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moehring, J. M., and T. J. Moehring. 1979. Characterization of the diphtheria toxin-resistance system in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Somatic Cell Genet. 5:453-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moehring, J. M., T. J. Moehring, and D. E. Danley. 1980. Posttranslational modification of elongation factor 2 in diphtheria-toxin-resistant mutants of CHO-K1 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:1010-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moehring, T. J., D. E. Danley, and J. M. Moehring. 1984. In vitro biosynthesis of diphthamide, studied with mutant Chinese hamster ovary cells resistant to diphtheria toxin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:642-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellecchia, M., T. Szyperski, D. Wall, C. Georgopoulos, and K. Wuthrich. 1996. NMR structure of the J-domain and the Gly/Phe-rich region of the Escherichia coli DnaJ chaperone. J. Mol. Biol. 260:236-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips, N. J., M. R. Zeigler, and L. L. Deaven. 1996. A cDNA from the ovarian cancer critical region of deletion on chromosome 17p13.3. Cancer Lett. 102:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips, N. J., M. R. Ziegler, D. M. Radford, K. L. Fair, T. Steinbrueck, F. P. Xynos, and H. Donis-Keller. 1996. Allelic deletion on chromosome 17p13.3 in early ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 56:606-611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose, M. D., P. Novick, J. H. Thomas, D. Botstein, and G. R. Fink. 1987. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae genomic plasmid bank based on a centromere-containing shuttle vector. Gene 60:237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schultz, D. C., L. Vanderveer, D. B. Berman, T. C. Hamilton, A. J. Wong, and A. K. Godwin. 1996. Identification of two candidate tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 17p13.3. Cancer Res. 56:1997-2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Ness, B. G., J. B. Howard, and J. W. Bodley. 1980. ADP-ribosylation of elongation factor 2 by diphtheria toxin. NMR spectra and proposed structures of ribosyl-diphthamide and its hydrolysis products. J. Biol. Chem. 255:10710-10716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.