Abstract

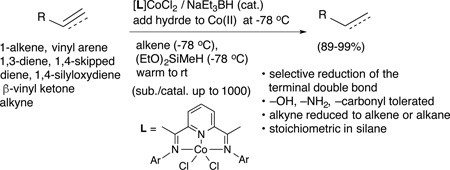

While attempting to effect Co-catalyzed hydrosilylation of β-vinyl trimethylsilyl enol ethers we discovered that depending on the silane, solvent and the method of generation of the reduced cobalt catalyst, a highly efficient and selective reduction or hydrosilylation of an alkene can be achieved. This paper deals with this reduction reaction, which has not been reported before in spite of the huge research activity in this area. The reaction, which uses an air-stable [2,6-di(aryliminoyl)pyridine)]CoCl2 activated by 2 equivalents of NaEt3BH as a catalyst (0.001–0.05 equiv) and (EtO)2SiMeH as the hydrogen source, is best run at ambient temperature in toluene and is highly selective for the reduction of simple unsubstituted 1-alkenes and the terminal double bonds in 1,3- and 1,4-dienes, β-vinyl ketones and silyloxy dienes. The reaction is tolerant of various functional groups such as a bromide, alcohol, amine, carbonyl, and di or trisubstituted double bonds, and water. Highly selective reduction of a terminal alkyne to either an alkene or alkane can be accomplished by using stoichiometric amounts of the silane. Preliminary mechanistic studies indicate that the reaction is stoichiometric in the silane and both hydrogens in the product come from the silane.

Keywords: cobalt catalysis, selective hydrogenation, hydrosilylation, ligand effects, dienes, hydrogenation

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

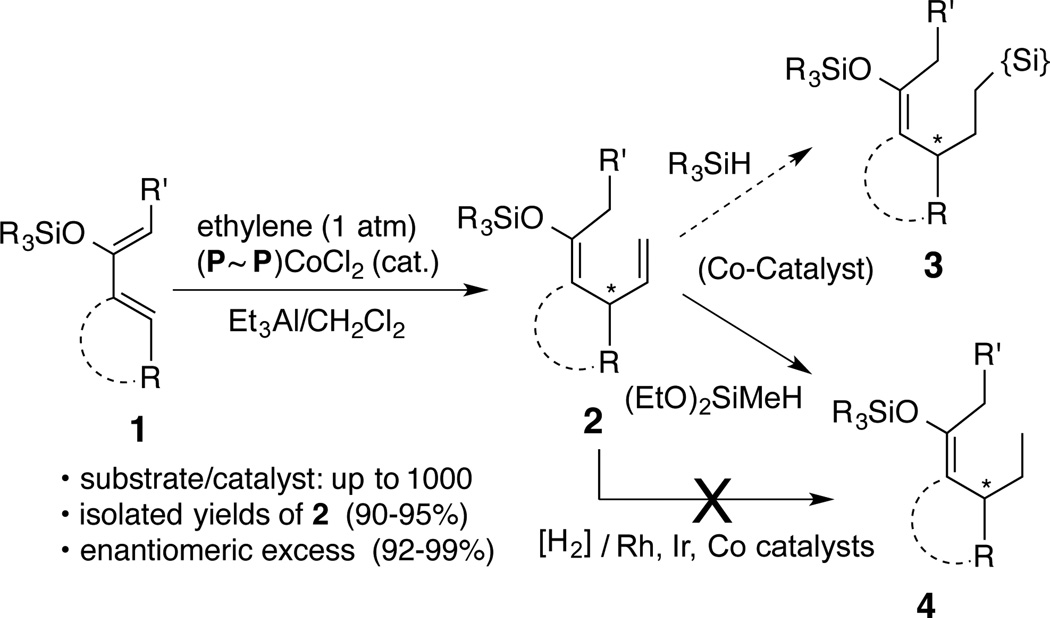

We recently reported a general procedure for a catalytic enantioselective synthesis of trialkylsilyl enol ethers (2) bearing a vinyl group on a chiral β-carbon center via hydrovinylation of 2-silyloxy-1,3-dienes (1) (Scheme 1).1 Further synthetic value of these functionalized enolates could be realized from their subsequent chemo-, regio- and stereoselective reactions. In this regard, a class of reactions that would lead to many different useful intermediates is the selective hydrofunctionalization2 of the terminal alkene in a product like 2 without affecting the silyl enol ether moiety, which in turn can be used for subsequent reactions with electrophiles. We found3 that one version of a cobalt-catalyzed hydrosilylation is such a reaction that can be accomplished with varying degree of success by the proper choice of the catalyst, reducing agent, solvent and an appropriate silane to give 3 in high yield and selectivity.4 During these investigations, we also discovered that (EtO)2Si(Me)H as a unique reagent capable of affecting an exceptionally selective reduction of the terminal alkene in 2 to give the silyl enol ether product 4. Thus a combination of this silane, an in situ generated Co(I)-2,6-di(aryliminoyl)pyridine [Co(I)-(PDI)] catalyst and toluene as a solvent was found to be critical for the success of this reaction, which is distinctly different from the atom-transfer hydrogenations recently reported by Shenvi5,6 and Herzon.7,8 They carried out such reactions under oxidative conditions similar to the classical Mukaiyama protocol,9 which involves the use of stoichiometric amounts of an oxidant (e. g., t-butyl hydroperoxide) in addition to the silane. Attendant problems of such a protocol for oxidatively sensitive substrates we are interested in (e.g., 2) are obvious. Classical hydrogenation reactions using Rh, Ir and Co catalysts failed to deliver 4 (vide infra). Other reactions that involve hydrogen atom transfer steps under neither oxidizing nor reducing conditions lead to isomerization reactions, not simple reductions.10,11 The highly selective reactions reported in this paper have selectivities that are distinctly different from several cobalt and iron-catalyzed hydrogenation reactions reported recently.12 We have since found that this reaction has wide scope beyond the originally intended substrates, including for semi-reduction terminal alkynes. While the use of stoichiometric amount of a silane is a minor detraction from an atom economy perspective, an operationally simple, highly efficient (typically 90–100% yield), selective and catalytic (up to 0.001 equiv of cobalt) hydrogenation protocol that does not involve the use hydrogen gas or pressure reactors does have some attraction for lab-scale preparations. Here we provide the details of these studies.

Scheme 1.

Chemoselective Hydrosilylation and Reduction of Silyloxy-1,4-dienes.

Results and Discussion

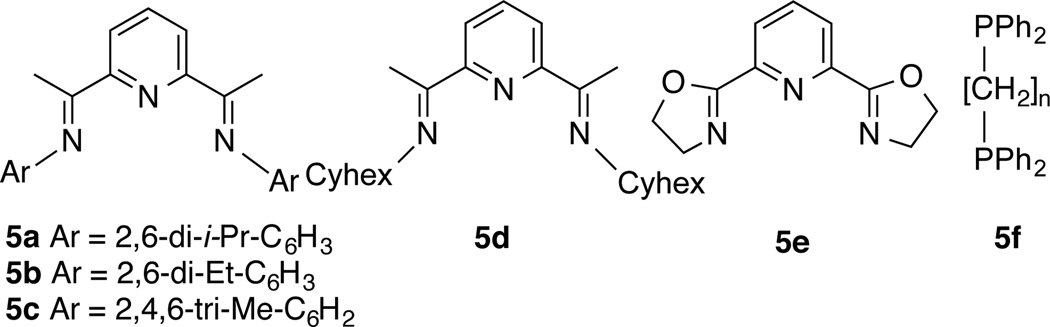

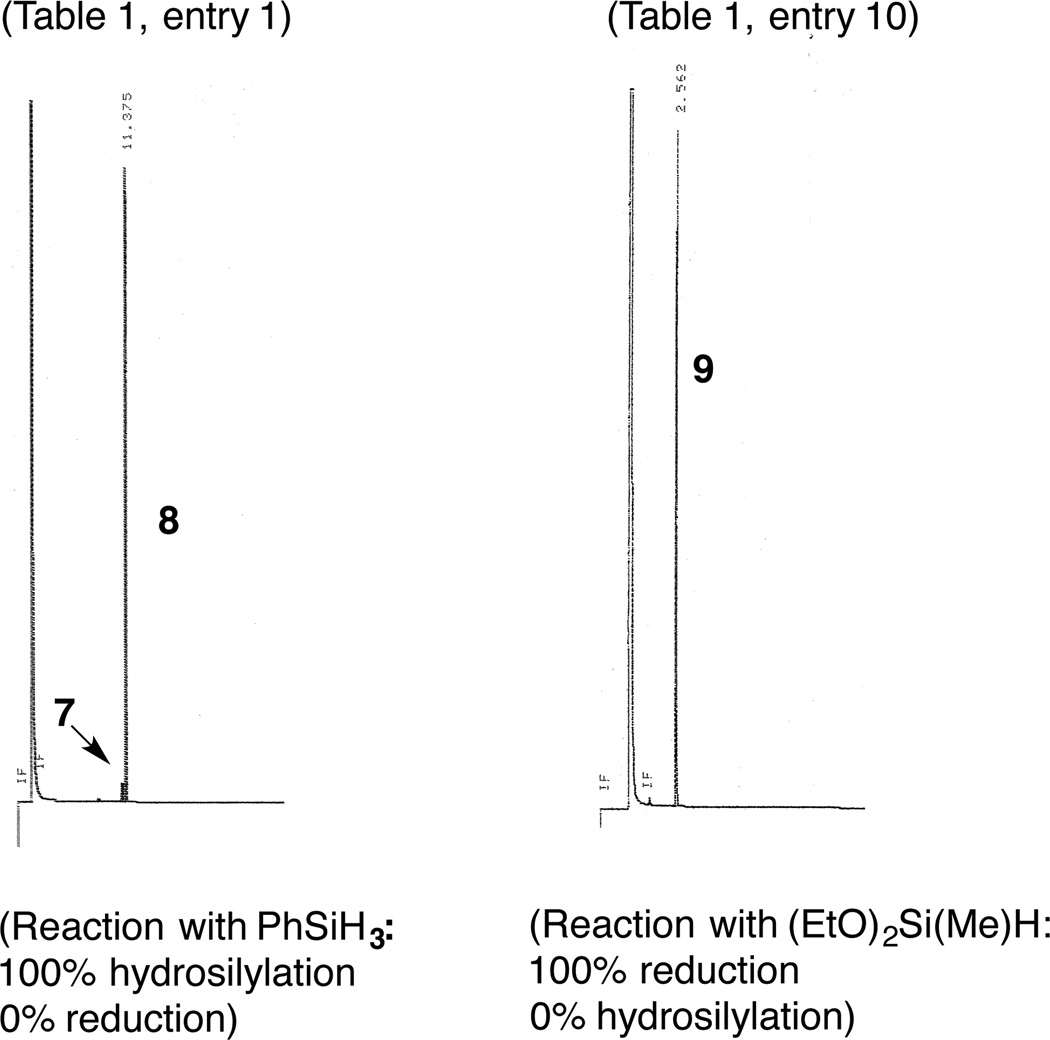

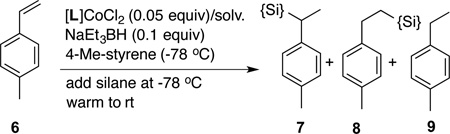

Our investigations started with an examination of the reactions of various silanes with a prototypical substrate, 4-methylstyrene. In initial scouting of a series of 1,n-bis-diphenylphosphinoalkanes (n = 1–4) and bisimine Co(II)-complexes (Figure 1) we identified the 2,6-diaryliminopyridine (PDI) ligands (5a–d),13 in particular the 2,6-diisopropyl derivative (5a) to be the most optimum ligand for these reactions. A quick survey of most commonly used activators (trimethyl aluminum, MeLi, EtMgBr, n-BuLi, and NaEt3BH) confirmed that NaEt3BH14 at −78 °C is the best reagent for reduction of the [PDI]CoCl2 complex for our purpose.15 Reactions of various commercially available silanes with 4-methylstyrene using a combination of [iPr-PDI]CoCl2 (5a) and NaEt3BH as a catalyst are shown in Eq 1 and Table 1. In a typical procedure, the Co-complex (0.001–0.05 equiv) and the alkene (1 equiv) are dissolved in the appropriate solvent under argon and the mixture is cooled to −78 °C. To this solution is added a toluene solution of NaEt3BH (0.002–0.1 equiv) followed by the silane (1.0–1.1 equiv). The mixture is slowly warmed to rt while monitoring the reaction by gas chromatography (GC) and GC-mass spectrometry. After the completion of the reaction, the mixture is passed over a pad of silica using hexane as an eluent to remove ligand residues and the insoluble silicon-containing byproducts (as determined by MALDI) and the combined fractions are concentrated and analyzed by GC and NMR spectroscopy. Chromatograms of products from several preparative runs are included in the Supporting Information.

Figure 1.

Ligands (L) in Pre-catalyst [L]CoCl2 Used for Hydrosilylation/Reduction

Table 1.

Effect of Silane, Solvents on the Co-Catalyzed Reactions of 4-Methylstyrenea

| entry | silane | solvent time (h) |

products | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||

| 1 | PhSiH3 | tol/5 | 0 | 2 | 98 | 0 |

| 2 | Et2SiH2 | tol/12 | 0 | 2 | 78 | 17 |

| 3 | Ph3SiH | tol/12 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 4 | Cl3SiH | tol/12 | 87 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| 5 | Et3SiH | tol/12 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 36 |

| 6 | MePhSiH2 | tol/12 | 0 | 2 | 83 | 9 |

| 7 | Ph2SiH2 | tol/12 | 4 | 2 | 50 | 0 |

| 8 | (EtO)3SiH | tol/12 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 47b |

| 9 | (TMSO)2SiMeH | tol/5 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 47b |

| 10 | (EtO)2SiMeH | tol/5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100b |

| 11 | (EtO)2SiMeH | dcm/5 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 12 | (EtO)2SiMeH | THF/12 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 87 |

| 13 | (EtO)2SiMeH | hex/12 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 14 | (EtO)2SiMeH | ether/12 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 90 |

| 15 | (EtO)2SiMeH | dce/12 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 16 | (EtO)2SiMeH | C6H6/12 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 80 |

See Supporting Information for details. Ratios of products determined by GC.

No other products detected by GC or NMR.

tol. toluene; dcm dichloromethane; hex hexane; dce dichloroethane.

A careful examination of the data in Table 1 suggests that two kinds of products can be obtained in preparatively useful yields. Thus a primary silane, PhSiH3 gives an excellent yield of the linear silane 8 (entry 1). The same product is obtained as the major component in reactions with secondary silanes such as Et2SiH2, MePhSiH2 and Ph2SiH2 (entries 2, 6 and 7). Unlike the exquisitely selective PhSiH3, these reagents also yield varying amounts of a branched hydrosilylation product (7) and a reduction product (9). Tertiary silanes such as Ph3SiH, Cl3SiH, Et3SiH, (EtO)3SiH and (TMSO)2Si(Me)H are much less reactive and the starting 4-methylstyrene remains mostly unreacted for several hours at room temperature. In sharp contrast, another tertiary silane, (EtO)2SiMeH, is a remarkable reagent giving nearly quantitative yield of a reduction product 9 (entry 10). An examination of the solvent effect reveals that while hexane and chlorinated solvents such as CH2Cl2 and ClCH2CH2Cl are unsatisfactory, THF and diethyl ether lead to acceptable yields. In a parallel run using these solvents, the best solvent for the reaction was identified as toluene, where a quantitative yield of the reduction product, 9, uncontaminated by the starting material (6) or hydrosilyaltion product (8) was observed (entry 10).

|

(1) |

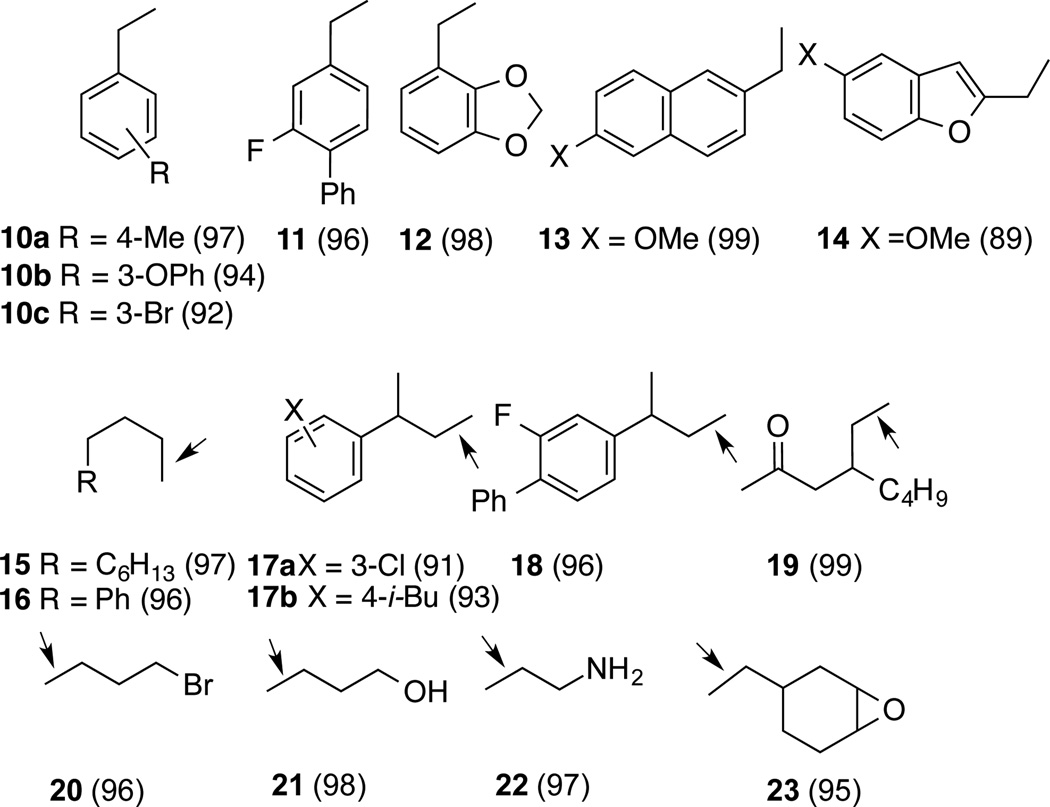

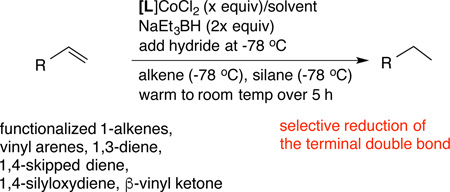

The highly selective silane-mediated reduction of the terminal alkene is a broadly useful reaction with applications in varied class of substrates. The optimized procedure for the reaction is shown in Eq 2 and the full scope of the reaction is illustrated by the examples shown in Figure 3.

|

(2) |

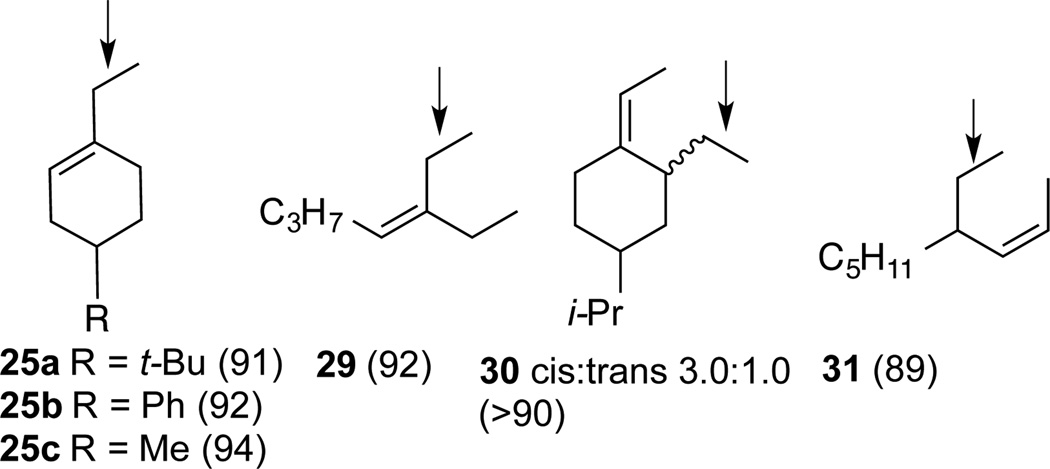

Figure 3.

Cobalt-Catalyzed Selective Reduction of Terminal Alkenes Mediated by Stoichiometric (EtO)2Si(Me)H (isolated yields in bracket). Arrow Shows the Position of Reduction. See Eq 2 and Supporting Information for Details.

As expected from the scouting studies, vinyl arenes (10–14) undergo exceptionally clean reduction to the corresponding saturated compounds. Particularly noteworthy is the retention of bromine in the aromatic ring in the example 10c which suggest the absence of Co(0) intermediates.16 3-Arylbutenes are a class of compounds especially prone to isomerization17–19 of the double bond under reactions that generate metal-hydrides to give products in which the double bond is in conjugation with the aryl ring. Reductions of 3-arylbutenes (17a, b and 18) proceed with no rearrangement to more stable conjugated products, precluding hydrogen-atom transfer processes, the likes of which are involved in the 1-alkene to 2-alkene isomerization catalyzed by Co-salen complexes reported by Shenvi.10 Terminal alkenes bearing carbonyl (19), Br (20), OH (21), NH2 (22) and epoxy (23) functionality are reduced in nearly quantitative yields. The products are isolated by simple filtration of the crude product through silica to remove what appears to be silicon-containing polymeric materials and residues from the catalyst.15 These reactions are easily scaled up without loss of yield or selectivity and several examples run on preparative scales are included in the Supporting Information.

|

(3a) |

|

(3b) |

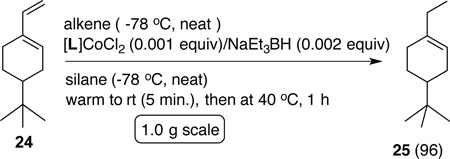

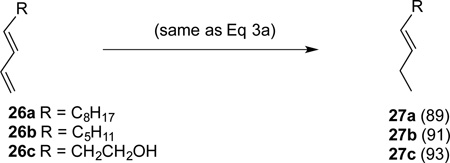

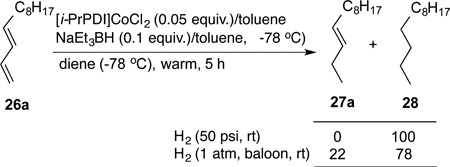

The most significant finding in this study is the highly selective reduction of the terminal double bond in 1,3-dienes. Two examples illustrated in Eq 3a and 3b. The selectivity in the reduction of the terminal double bond in the 1,3- (26a–c) and a 1,4-dienes (30 and 31, Figure 4) in the presence of the additional disubstituted double bond is unprecedented. Attempted hydrogenation of the diene 26a using a Co(PDI)-catalyst under hydrogenation conditions12g using hydrogen as the stoichiometric reductant gives complete reduction of both bonds at 50 psi (Eq 4). Even at 1 atmosphere hydrogen, competitive reduction ensues giving a mixture of reduction products 27a and 28 (Eq 4). Likewise, selective hydrogenation by cobalt (II)-complexes of bis[2-(dicyclohexylphosphino)ethyl]-amine also lack this selectivity between a mono- and disubstituted alkenes.20

|

(4) |

Figure 4.

Products of Selective Reduction of 1,3- and 1,4-Dienes

These reduction reactions can be accomplished in neat substrate using as little as 0.001 equiv (substrate/catalyst = 1000) of the catalyst. Examples of products from selective reduction of the terminal double bond in several 1,3- and 1,4- are shown in Figure 4. As indicated by gas chromatographic analysis of the crude products,15 these reactions are exceptionally clean and gave >90% isolated yields of the products. The less than quantitative yield of the products is a reflection of the volatility of the hydrocarbon products.

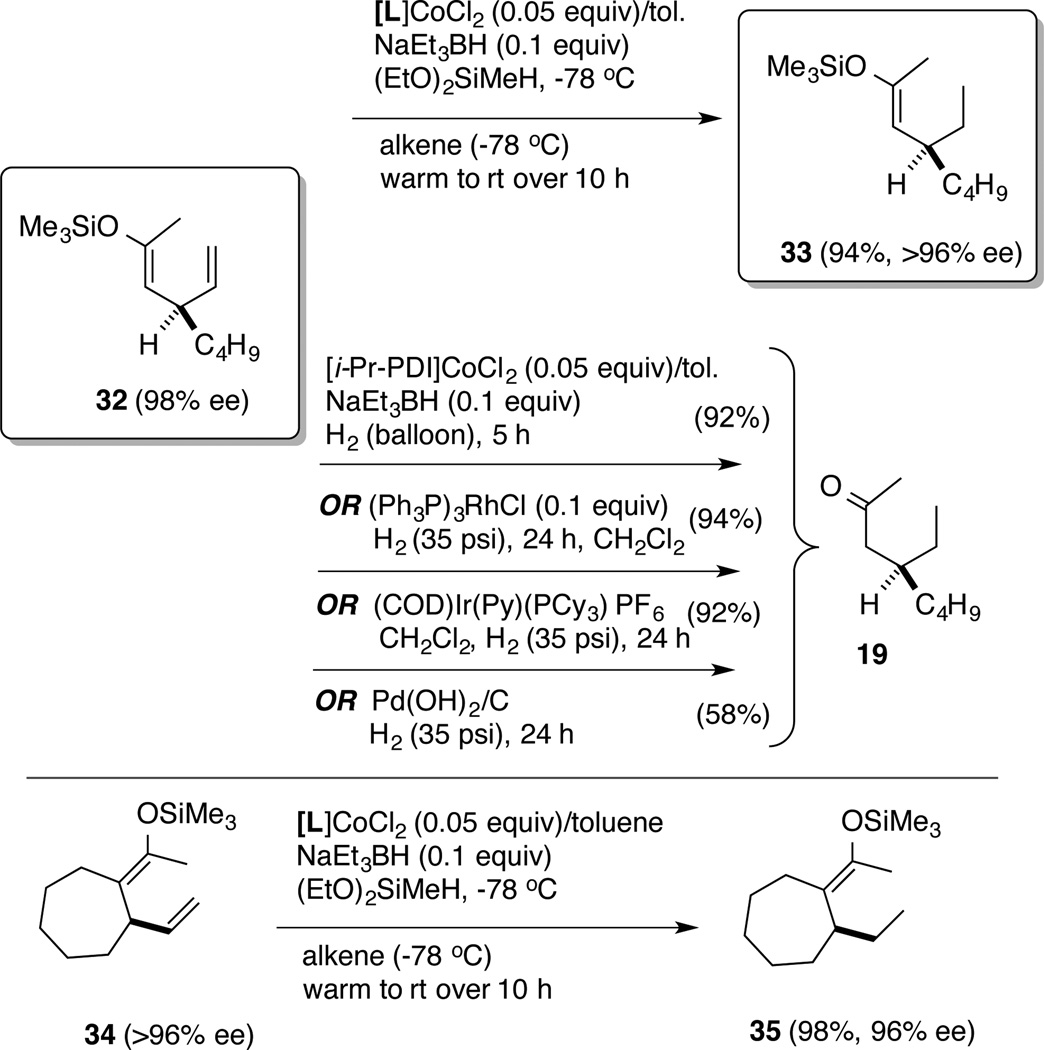

Returning to the highly sensitive β-vinyl silyl enolate derivatives (Scheme 1), we find that all attempts to reduce the terminal double bond in 32 (Scheme 2) via standard hydrogenation conditions using either the Wilkinson’s catalyst (Ph3P)3RhCl or Crabtree’s catalyst [(COD)Ir(Py)(PCy3)]+ [PF6]− gave a mixture of products including the ketone (Scheme 2). Well-known Co-hydrogenation catalysts12g also gave the ketone product 19. A heterogeneous catalyst, Pd(OH)2/carbon (Pearlman’s catalyst) leads to the same result, but in much poorer yields (Scheme 2). In sharp contrast, the (EtO)2SiMeH effects highly selective reduction of the terminal alkene in 32 giving excellent yield of the silyl enol ether 33. A related derivative 34 also underwent the reaction with no complications. The enantiomeric purity of the starting materials is not affected under these conditions, as revealed by chiral stationary phase gas chromatographic analysis of the products, where base-line separation of the starting materials (32 and 34) and products (33 and 35) can be observed.

Scheme 2.

Chemoselective Reduction of Siloxy-1,4-Dienes

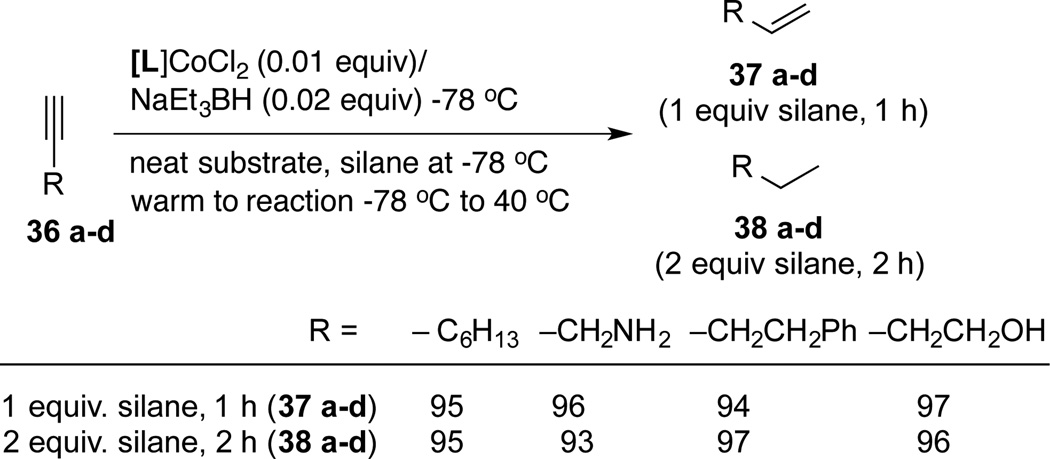

The new reduction protocol is applicable for the reduction of terminal alkynes either to the 1-alkene, or, to the completely reduced alkanes based on the stoichiometry of the silane used (Scheme 3). For example, using 1 equivalent of (EtO)2Si(Me)H and 0.01 equivalent of the catalyst a variety of terminal alkynes 36a–d are selectively reduced to 1-alkene 37a–d. Under the same conditions except using 2 equiv of the silane and slightly longer reaction times the alkanes 38a–d are formed in excellent yields. The rate of the second reduction (of the alkene to the alkanes) is slow enough to enable the isolation the intermediate alkene in excellent yields. As illustrated by the examples shown in the Scheme 3, the reaction is compatible with a variety of functional groups.

Scheme 3.

Selective Reduction of Alkynes

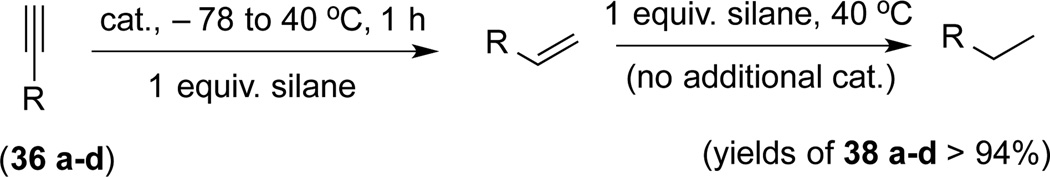

In a mechanistically relevant experiment, the two steps can be performed back-to-back in a single flask, first by adding 1 equivalent of the silane to a mixture of the alkyne and 0.01 equiv of the catalyst, fully characterizing the intermediate alkene, and then adding a second equivalent of the silane (no additional catalyst) and, isolating the saturated product (Scheme 4).15 There is no reduction of yields of the final products (38a–d) as compared to the single step operation described in Scheme 3.

Scheme 4.

Sequential Reduction of Alkyne Controlled by Stoichiometry of the Silane

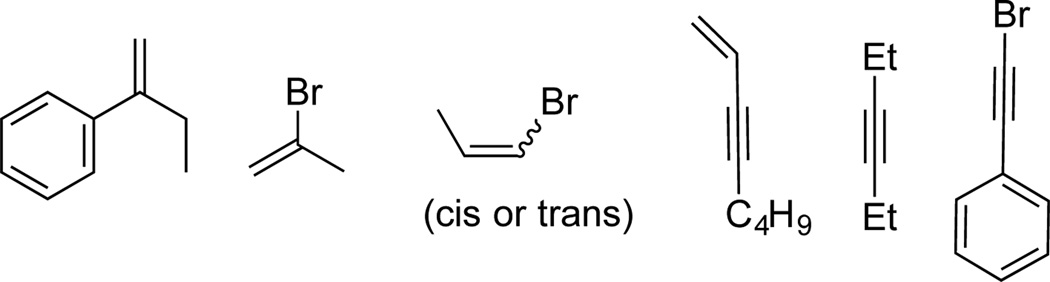

Finally under a variety of conditions the following substrates (Figure 5) failed to react, leaving behind unreacted starting materials even after prolonged reaction times.

Figure 5.

Unreactive Substrates

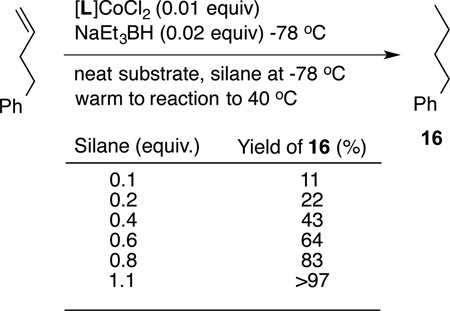

Mechanism of the (EtO)2Si(Me)H-mediated reduction, in particular the origin of the two hydrogens has not been ascertained with certainty primarily because of the difficulties in preparing the completely deuterated silane, which would involve the use specialized equipment and prohibitively expensive chemistry. But the following experiments provide strong circumstantial evidence to suggest that both hydrogens come from the silane. (i) Reduction of 4-phenyl-1-butene performed with 0.001 equivalent of the catalyst in either toluene-d8 or THF-d8, which are the best solvents for the reaction, show 0% incorporation of deuterium in the products (high resolution 1H NMR and mass spectrometry). (ii) No byproducts derived from THF or toluene are detectable by GC or GC-MS. (iii) The presence of excess D2O has no effect on the product composition, nor does added activated 4 Å sieves inhibit the reaction. These experiments rule out the unlikely role of any adventitious water as the source of hydrogen in these reactions. (iv) We have carried out a series of experiments in which the stoichiometry of the silane was varied and the yield of the reduction product determined from preparatively meaningful scale of 200 mg (1.51 mmol) of 4-phenylbutene. The results shown in Eq 5 and associated Table below confirm that the extent of conversion to the product is within experimental error of what would be expected in a reaction that is stoichiometric in the silane. These experiments suggest the possibility that the silane is the sole source of hydrogen. The ultimate fate of the silane reagent is currently not known, even though a white gelatinous material isolated upon evaporation of the solvents at the end of the reaction suggests oligomeric silyl compounds as determined by mass spectrometry (MALDI). Fortuitously the formation of this material (siloxane polymer?), which is easily removed by filtration through silica gel, also makes the isolation of the products exceptionally easy.

|

(5) |

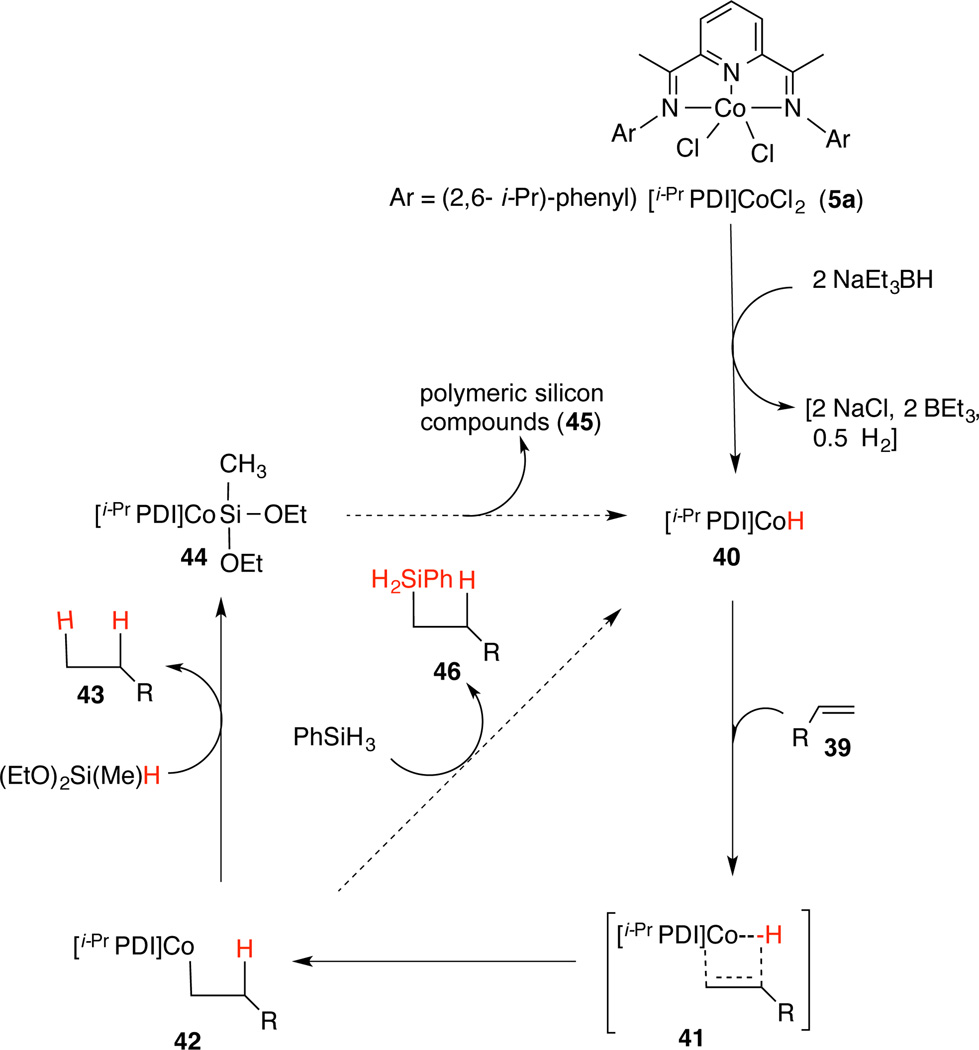

Based on the available evidence we suggest a mechanism shown in Scheme 5. Reduction of the (PDI)CoCl2 complex 5a with two equivalents of NaBEt3H can be expected to give a Co(I)-H intermediate (40).14 Reduced ClCo(iPrPDI)21 in itself or in the presence of Et3B does not catalyze the reaction. However, reduced ClCo(iPrPDI) in the presence of 1 equiv of NaBEt3H is an effective catalyst for the reaction. Viability of a metal hydride in the initial step in hydrogenation of an alkene has been established before.12g Intermediacy of the metal hydride (40) might also explain why chlorinated solvents such as CH2Cl2 are ineffective for the reaction, since LCo(I)-hydride can be presumed to react with a chlorinated solvent under these conditions.20 Insertion of the alkene into the Co-H bond gives a primary Co-alkyl complex (42), which upon reaction with the silane could give the product 43. The reactivity of 42 with different silanes might account for the dramatic difference in hydrogenation vs hydrosilylation activity depending on the silane structures. For example, the exclusive hydrosilylation activity seen with PhSiH3 [e.g., formation of 46 [(R = p-tolyl), Table 1, entry 1] maybe explained by a σ–bond metathesis of the C-Co bond in 42 with this reagent giving the hydrosilylation product (46), rather than the hydrogenation product (43) seen when (EtO)2SiMeH is employed. Finally, careful monitoring of the reaction from very early stages of provide no indication that the silane undergoes metathesis reactions producing any other polyhydrides.22

Scheme 5.

Plausible Mechanism of Silane-Mediated Hydrogenation/Hydrosilylation

In conclusion, we describe a new, experimentally simple protocol for a highly selective reduction of mono-substituted alkenes including those in 1,3- and 1,4-dienes using (EtO)2Si(Me)H as a stoichiometric reducing agent. The reaction is carried out in the presence of catalytic amounts of a readily available air-stable [2,6-di(aryliminoyl)pyridine)]-CoCl2 and NaEt3BH. Substrates carrying alcohols, bromides, amines, carbonyl groups or other di- and tri-substituted alkenes are tolerated. Terminal alkynes are reduced to 1-alkenes or to the corresponding alkanes depending on the amount of silane used. The reaction is highly dependent on the silane and the solvent, with (EtO)2Si(Me)H and toluene giving nearly quantitative yields of the expected products. Preliminary mechanistic studies indicate that the reaction is stoichiometric in the silane and both hydrogens in the product come from the silane.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

GC Traces of Crude Products Showing Uncommon Selectivity with Two Different Silanes

Acknowledgments

Financial assistance for this research provided by US National Science Foundation CHE-1362095 and National Institutes of Health (R01GM 108762). Authors thank Stanley Jing of this department for providing some of the (PDI)CoCl2 com-plexes for early scouting experiments.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures for the scouting experiments, syntheses and isolation of the hydrogenation products. Spectroscopic and gas chromatographic data showing compositions of products under various reaction conditions. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

The authors declare no financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biswas S, Page JP, Dewese KR, RajanBabu TV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:14268. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a recent review, see: Greenhalgh MD, Jones AS, Thomas SP. Chem Cat Chem. 2015;7:190.

- 3.These results were presented at the 251st National ACS Meeting in San Diego, Abstract ORGN 427. The results of the hydrosilyaltion will be reported separately.

- 4.Non-precious metal catalysis of hydrosilylations of of alkenes and alkynes have attracted considerable attention recently. For recent reviews see: Sun J, Deng L. ACS Catal. 2016;6:290. Nakajima Y, Shimada S. RSC Adv. 2015;5:20603. After our studies were completed several notable papers that deal with hydrosilyaltion of alkenes have appeared: Schuster CH, Diao T, Pappas I, Chirik PJ. ACS Catal. 2016;6:2632. Chen C, Hecht MB, Kavara A, Brennessel WW, Mercado BQ, Weix DJ, Holland PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:13244. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08611. Noda D, Tahara A, Sunada Y, Nagashima H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:2480. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11311. Buslov I, Becouse J, Mazza S, Montandon-Clerc M, Hu X. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:14523. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507829. For an enantioselective version, see: Chen J, Cheng B, Cao M, Lu Z. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:4661. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411884. Fe-catalyzed hydrosilylations: Sunada Y, Noda D, Soejima H, Tsutsumi H, Nagashima H. Organometallics. 2015;34:2896. Greenhalgh MD, Frank DJ, Thomas SP. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014;356:584. Tondreau AM, Atienza CCH, Weller KJ, Nye SA, Lewis KM, Delis JGP, Chirik PJ. Science. 2012;335:567. doi: 10.1126/science.1214451. Kamata K, Suzuki A, Nakai Y, Nakazawa H. Organometallics. 2012;31:3825. Brookhart M, Grant BE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:2151. 1,4-Hydrosilylation of 1,3-dienes: Wu JY, Stanzl BN, Ritter T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13214. doi: 10.1021/ja106853y. Hilt G, Lüers S, Schmidt F. Synthesis. 2004:634. For a 1,6-di(aryliminoyl)pyridine-cobalt-catalyzed dehydrogenative hydrosilylation, see: Atienza CCH, Diao T, Weller KJ, Nye SA, Lewis KM, Delis JGP, Boyer JL, Roy AK, Chirik PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12108. doi: 10.1021/ja5060884.

- 5.Obradors C, Martinez RM, Shenvi RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:4962. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki K, Wan KK, Oppedisano A, Crossley SWM, Shenvi RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:1300. doi: 10.1021/ja412342g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King SM, Ma X, Herzon SB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:6884. doi: 10.1021/ja502885c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma X, Herzon SB. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:6250. doi: 10.1039/c5sc02476e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mukaiyama T, Yamada T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1995;68:17. See also: Mukaiyama T, Isayama S, Inoki S, Kato K, Yamada T, Takai T. Chem. Lett. 1989;18:449. Nishinaga A, Yamada T, Fujisawa H, Ishizaki K, Ihara H, Matsuura T. J. Mol. Catal. 1988;48:249. Kato K, Yamada T, Takai T, Inoki S, Isayama S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1990;63:179.

- 10.Crossley SWM, Barabé F, Shenvi RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:16788. doi: 10.1021/ja5105602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li G, Kuo JL, Han A, Abuyuan JM, Young LC, Norton JR, Palmer JH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:7698. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Co-catalyzed hydrogenation of alkenes using hydrogen gas: A review: Chirik PJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:1687. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00134. For other key referencs, see: Zhang G, Scott BL, Hanson SK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:12102. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206051. Monfette S, Turner ZR, Semproni SP, Chirik PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4561. doi: 10.1021/ja300503k. Friedfeld MR, Shevlin M, Hoyt JM, Krska SW, Tudge MT, Chirik PJ. Science. 2013;342:1076. doi: 10.1126/science.1243550. Chen J, Chen C, Ji C, Lu Z. Org. Lett. 2016;18:1594. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00453. Yu RP, Darmon JM, Milsmann C, Margulieux GW, Stieber SCE, DeBeer S, Chirik PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:13168. doi: 10.1021/ja406608u. Knijnenburg Q, Horton AD, Heijden Hvd, Kooistra TM, Hetterscheid DGH, Smits JMM, Bruin Bd, Budzelaar PHM, Gal AW. J. Mol. Catal. A. Chem. 2005;232:151. (h) Use of Fe-catalysts with redox active PDI ligands: Trovitch RJ, Lobkovsky E, Bill E, Chirik PJ. Organometallics. 2008;27:1470.

- 13.PDI and related redox-active ligands have a long history in cobalt-mediated polymerization and hydrofunctionalization reactions: Small BL, Brookhart M, Bennett AMA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4049. Britovsek GJP, Bruce M, Gibson VC, Kimberley BS, Maddox PJ, Mastroianni S, McTavish SJ, Redshaw C, Solan GA, Strömberg S, White AJP, Williams DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:8728. Zhu D, Thapa I, Korobkov I, Gambarotta S, Budzelaar PHM. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:9879. doi: 10.1021/ic2002145. For two recent reports on hydrosilylation and hydrogenation, see: (d) ref. 4c. (e) ref. 12f.

- 14.For the first use of NaEt3BH for these types of activation, see: Bart SC, Chłopek K, Bill E, Bouwkamp MW, Lobkovsky E, Neese F, Wieghardt K, Chirik PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13901. doi: 10.1021/ja064557b.

- 15.See Supporting Information for details.

- 16.Zhu D, Budzelaar PHM. Organometallics. 2010;29:5759. [Google Scholar]

- 17.RajanBabu TV, Nomura N, Jin J, Nandi M, Park H, Sun XF. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:8431. doi: 10.1021/jo035171b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim HJ, Smith CR, RajanBabu TV. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:4565. doi: 10.1021/jo900180p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biswas S, Zhang A, Raya B, RajanBabu TV. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014;356:2281. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201400237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang G, Scott BL, Hanson SK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:12102. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kooistra TM, Knijnenburg Q, Smits JMM, Horton AD, Budzelaar PHM, Gal AW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:4719. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4719::aid-anie4719>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buslov I, Keller SC, Hu X. Org. Lett. 2106;18:1928. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.