Abstract

The current investigation evaluated whether cognitive processes characteristic of the Social Information Processing model predicted parent-child aggression (PCA) risk independent of personal vulnerabilities and resiliencies. This study utilized a multimethod approach, including analog tasks, with a diverse sample of 203 primiparous expectant mothers and 151 of their partners. Factors considered in this study included PCA approval attitudes, empathy, reactivity, negative child attributions, compliance expectations, and knowledge of non-physical discipline alternatives; additionally, vulnerabilities included psychopathology symptoms, domestic violence victimization, and substance use, whereas resiliencies included perceived social support, partner relationship satisfaction, and coping efficacy. For both mothers and fathers, findings supported the role of greater approval of PCA attitudes, lower empathy, more overreactivity, more negative attributions, and higher compliance expectations in relation to elevated risk of PCA. Moreover, personal vulnerabilities and resiliencies related to PCA risk for mothers; however, fathers and mothers differed on the nature of these relationships with respect to vulnerabilities as well as aspects of empathy and PCA approval attitudes. Findings provide evidence for commonalities in many of the factors investigated between mothers and fathers with some notable distinctions. Results are discussed in terms of how findings could inform prevention programs.

Keywords: Physical child abuse potential, Social information processing theory, Resiliency, Child abuse risk, Cognitive risk factors, Transition to parenting

Introduction

Child abuse represents a critical public health concern, with an estimated 702,000 victims substantiated by child protective services in 2014, 17 % of which involved physical maltreatment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2016). But considerably more maltreatment transpires in the U.S. given substantial underreporting to protective services agencies, particularly with regard to physical maltreatment (Sedlak et al. 2010). Physical maltreatment often arises during a physical discipline episode in which parents escalate the intensity of physical discipline (Durrant et al. 2009; Kadushin and Martin 1981). Parents who routinely employ spanking are three times as likely to be substantiated for maltreatment (Durrant et al. 2009). Similarly, early parental spanking of infants by age one predicts future child protective services involvement (Lee et al. 2014). Given the context within which physical abuse thus arises, many view abuse as occurring on a parent–child aggression (PCA) continuum (Gershoff 2010; Graziano 1994; Greenwald et al. 1997; Rodriguez, 2010a; Straus 2001; Whipple and Richey 1997), wherein physical discipline at one endpoint progressively intensifies to become physical abuse at the other endpoint.

Child abuse potential reflects a parent’s likelihood to progress along such a continuum toward physical abuse, comprising the interpersonal and intrapersonal problems characterizing perpetrators of physical abuse (Milner 1986). Child abuse potential is associated with abusive discipline tactics (Rodriguez 2010b) as well as harsh and authoritarian parenting (Haskett et al. 1995; Margolin et al. 2003; Rodriguez et al. 2016). To prevent child abuse before it occurs, identifying factors predicting child abuse potential is essential. We thus include abuse potential and authoritarian parenting and practices to capture a broad view of points along the PCA continuum to investigate what induces parents to apply harsh physical discipline that can intensify into physical abuse.

A theoretical framework serves to integrate possible risk factors and processes that culminate in parents’ becoming physically abuse, delineating specific targets for child abuse prevention efforts. For example, Social Information Processing (SIP) theory proposes that a number of cognitive-behavioral processes unfold to lead parents to engage in physical abuse (Milner 2000). SIP theory postulates that parents hold preexisting schemas before a discipline situation even arises. Then, according to SIP theory, when a parent is faced with a discipline situation, four processes occur: the parent must accurately perceive the situation (Stage 1); the parent develops interpretations and expectations about the situation (Stage 2); the parent may fail to integrate all necessary information to elect a response to the situation, including consideration of alternative discipline responses (Stage 3); and parents who select PCA may have difficulty monitoring its administration in this final cognitive-behavioral phase (Stage 4).

This SIP model contends that preexisting schemas affect each stage and each stage in turn prompts aggression toward children. Preexisting schemas can include belief structures (e.g., about children and discipline) as well as affective schemas acquired from previous social interactions. Indeed, researchers applying SIP to children’s aggressive behavior advocate an explicit integration of affective elements into sociocognitive processing (Crick and Dodge 1994). For example, empathy has been suggested as a preexisting positive affective state that can inhibit PCA (Milner 2000). Empathic parents who enter a discipline situation with such positive affective schema would be less inclined to engage in PCA.

Current research supports SIP theory in a number of ways. Several SIP elements were assessed separately in relation to mothers’ PCA risk, but the model was not considered as a whole (Montes et al. 2001). Studies confirm a subset of SIP processes in PCA risk, particularly with mothers (e.g., McElroy and Rodriguez 2008; Rodriguez 2010b; Rodriguez and Richardson 2007), although some work has begun to apply SIP to fathers’ risk (Rodriguez et al. 2016). A number of studies provide evidence for individual schemas in PCA risk that drove the development of SIP theory as applied to PCA (Milner 2000).

Specifically with regard to research on preexisting schemas, several studies indicate attitudes approving of physical discipline and parent–child aggression are linked to child abuse risk (e.g., Bower-Russa et al. 2001; Crouch and Behl 2001; Rodriguez et al. 2011). In terms of preexisting positive affect states, empathy can reduce aggression (Richardson et al. 1994). Low empathy has been observed in abusive mothers (Mennen and Trickett 2011) and high-risk parents (Perez-Albeniz and de Paul 2004), and has been associated with increased child abuse potential in low and at-risk samples (Rodriguez 2013; McElroy and Rodriguez 2008).

SIP Stage 1 processes interfere with accurate perceptions and parents who overreact may fail to attend carefully to the discipline situation (Milner 2000). Increased reactivity is often associated with child abuse risk (see Stith et al. 2009 for review). In part, such reactivity implies that parents may not manage their emotional response to the situation, reacting with frustration. Indeed, new mothers frustrated by infant crying report poor emotion regulation (Russell and Lincoln 2016). Although poor frustration tolerance and emotion dysregulation are not well studied in the context of abuse risk, some work suggests poor emotion regulation (Hien et al. 2010) and low frustration tolerance (Rodriguez et al. 2015) may relate to elevated child abuse potential. Thus, over-reactive frustration may distract from careful attention to a discipline situation.

With regard to Stage 2 processes involving expectations and interpretations, biased negative attributions regarding children’s behavior have garnered the most attention in the literature. Negative attributions toward children are observed in high risk mothers (Montes et al. 2001) as well as abusive mothers (Haskett et al. 2006). Such negative attributions in pregnant women can predict the likelihood of later harsh parenting and maltreatment (Berlin et al. 2013). Relatively less research has investigated expectations regarding compliance, also recognized as a Stage 2 process (Milner 2000). However, the limited research suggests high-risk mothers may expect more compliance from children (Chilamkurti and Milner 1993). Collectively, Stage 2 combines the attributions and expectations that may bias a parent’s appraisals and decisions in a discipline encounter.

Finally, with regard to Stage 3 where the parent integrates available information in order to select a discipline response, a parent may be limited in their knowledge of options for how to respond to the situation (Milner 2000). Indeed, enhancing parenting skills by encouraging non-physical discipline strategies characterizes a number of prevention and intervention programs intended to reduce PCA risk (e.g., Prinz et al. 2009; Webster-Stratton and Reid 2010).

Clearly these cognitive processes arise within the broader context of the parent’s life. In fact, parents’ SIP schemas are embedded within the wider ecological model historically applied to child maltreatment (Belsky 1993). SIP schemas can be viewed as components of the epicenter of ecological theory. Apart from cognitive processes, additional factors—unrelated to parenting—impinge upon the parent to further exacerbate or mitigate their abuse risk. Namely, the parent may experience personal vulnerabilities (e.g., psychopathology) that function to “tax” the parent, compromising their parenting. Conversely, this broader context can include personal resiliencies that serve as “resources,” for a parent that reduce abuse risk.

Research attests to the role of a number of personal vulnerabilities in increasing PCA risk. Of these personal issues, psychopathology emerges as a strong predictor of PCA (Ammerman and Patz 1996; Stith et al. 2009), although others have also recognized parents’ experience of intimate partner violence (Casanueva and Martin 2007; Margolin et al. 2003) and substance use (Ammerman et al. 1999; Hien et al. 2010) predict abuse risk. Such environmental strains on a parent likely tax a parent’s ability to effectively manage discipline situations. Remarkably little research, in contrast, has evaluated how parents’ resources are linked to reduced PCA risk. The most well documented resource in the literature is social support, which can decrease PCA risk (Rodriguez and Tucker 2015), particularly for mothers but not, perhaps, for fathers (Schaeffer et al. 2005). Partner satisfaction may be an additional social support that could offset risk, given that poorer relationship satisfaction predicts child abuse potential (Florsheim et al. 2003). Finally, the limited work on parental coping skills suggests its role in abuse risk is either positive or nonexistent (see Black et al. 2001 for review). Overall, however, studies have not yet adequately evaluated how such taxes and resources operate in concert with a wide range of cognitive processes.

Because many of the SIP processes (particularly preexisting schemas) may predate parenthood, evaluating such elements among first-time expectant parents represents an opportunity to identify early indicators of PCA risk. Many SIP schemas of interest can be targeted in prevention efforts to offset trajectories whereby physical discipline escalates along the PCA continuum. Indeed, current PCA prevention efforts typically concentrate on women during pregnancy (e.g., Ammerman et al. 2014; Bugental et al. 2002), highlighting the importance of studying this group.

Researchers have also long been urged to investigate fathers in maltreatment research (Lee et al. 2009; Milner and Dopke 1997; Stith et al. 2009) but the inchoate literature remains ambiguous on factors relevant to paternal abuse risk. Fathers are implicated in approximately half of those engaging in physical maltreatment (Sedlak et al. 2010). Current evidence implies fathers demonstrate comparable risk profiles to mothers, with modest differences (e.g., Rodriguez et al. 2016; Schaeffer et al. 2005; Smith Slep and O’Leary 2007). However, low couple satisfaction and low social support may be more problematic for mothers’, rather than fathers’, PCA risk (Schaeffer et al. 2005; Price-Wolff 2015). Others have reported that higher abuse risk fathers report less empathic perspective-taking ability—a finding not mirrored in mothers (Perez-Albeniz and De Paul 2004)–whereas empathy was less apparent as a risk factor in a model of PCA risk in fathers (Rodriguez et al. 2016). Nonetheless, relatively few direct comparisons of comprehensive abuse risk models have been performed between mothers and fathers.

Extant research in this field, however, often depends on the candor of participants’ self-report of their attitudes and beliefs despite widespread recognition this approach is vulnerable to participant distortion. Particularly with sensitive topics, respondents may either purposefully or subconsciously present themselves in a socially desirable manner (DeGarmo et al. 2006). Self-report methods are an explicit mechanism to assess a construct of interest; in contrast, analog tasks are implicit approaches that are less obvious to the participant, in which the intent and/or scoring of the implicit task is obfuscated, complicating the respondent’s ability to manipulate their response (Fazio and Olson 2003). Analog approaches can serve as useful adjuncts to the data derived from traditional self-report methods (Nosek 2007). Analog tasks can differ on the degree to which the participant can surmise the intent or scoring of the task, wherein less explicit tasks activate less conscious response selection by the participant (Fazio and Olson 2003).

Additionally, research often relies on individual indicators to estimate a construct of interest, but such an approach may not adequately comprise all relevant aspects of the construct (Hughes et al. 1986). Alternatively, multiple measures allow the weaknesses of one measure to be mitigated by other measures, avoiding such overreliance; for instance, often independent variables are assessed with single indicators containing items that overlap with the dependent variables, an issue that can be minimized with multiple measures. Multiple indicator approaches have become increasingly popular, particularly when based in theory (Little et al. 1999). Therefore, because multimethod strategies are regarded as ideal (Eid and Deiner 2006), several analog strategies supplemented self-report approaches in our multiple indicator model predicting PCA risk.

The present investigation represents the most comprehensive test of SIP theory to date with the additional benefit that SIP elements were evaluated in conjunction with the parent’s personal taxes (psychopathology, substance use, domestic violence) as well as personal resources (social support, partner satisfaction, coping). Such an inclusive evaluation can clarify whether those SIP processes relate to abuse risk independent of taxes and resources. PCA risk was represented by a wide range of markers along the PCA continuum, including higher child abuse potential, greater expected authoritarian parenting, and harsher expected reactions to noncompliant and compliant child behavior. The SIP model proposes preexisting schemas affect each stage collectively to then predict PCA, but the current investigation proposes specific pathways. Based on patterns observed in earlier work (Rodriguez et al. 2016), empathy, as an affectively themed preexisting schema, was hypothesized to relate in a specific pathway of subsequent SIP processes. Low empathy was expected to relate to compromised parents’ attention processes, wherein parents overreact, leading them to not attend to the discipline situation adequately or accurately (Stage 1). Moreover, low empathy may promote more negative attributions of child behavior (Stage 2) which in turn relates to increased PCA risk. Alternatively, preexisting attitudes accepting of PCA were expected to relate to a specific sequence pertaining to discipline schemas, directly linked to parents’ higher expectations of compliance following a discipline episode (Stage 2) and limited knowledge of non-physical discipline alternatives (Stage 3), thereby predicting increased PCA risk. Consequently, the current study incorporates major components of the SIP model with several personal taxes and resources to consider a theoretically grounded model for maternal and paternal risk employing a multimethod approach including several analog tasks and a direct comparison between mothers and fathers.

Method

Participants

The sample included 203 primiparous women and 151 male partners. Average age of expectant mothers was 26.03 years (SD = 5.87, range 16–40) and 28.91 years for expectant fathers (SD = 6.10, range 18–48). In terms of expectant mothers’ race/ethnicity, 51.2 % self-identified as Caucasian, 46.8 % African-American, 1 % Asian, and 1 % Native American/Alaskan; 3 % of these mothers also identified as Hispanic/Latina and 5.9 % also identified as bi-racial. For expectant fathers, 53.6 % identified as Caucasian, 45.7 % as African-American, and .7 % as Other; additionally, 2.6 % of these fathers also identified as Hispanic/Latino and 4 % identified as bi-racial. Approximately 87 % of mothers reported they were in a relationship with the father of the expected child. Highest educational attainment for mothers was: 30.5 %, high school diploma or less; 21.2 %, some college or vocational training; 21.25 %, college degree; remainder beyond a bachelor’s degree. Highest educational attainment for expectant fathers was: 25.5 %, high school diploma or less; 25.2 %, some college or vocational training; 27.2 %, college degree; remainder beyond a college degree. Nearly 43 % of expectant mothers were receiving federal public assistance, 46.3 % of the mothers were living within 150 % of the federal poverty line, and over 50 % reported an annual household income below $40,000 for an average family size of two.

Procedure

Participants were families from an ongoing prospective longitudinal study, the “Following First Families: Triple-F study”, tracking the evolution of PCA risk in first-time families in a large, urban city in the Southeast (see also Rodriguez et al. 2016; NIH 2016). The current analysis is based on all families enrolled in the first wave of the study. Participants were recruited with flyers distributed at local hospitals’ obstetric/gynecological clinics and associated childbirth courses. Primiparous expectant mothers in their final trimester contacted the lab to arrange a 2–2½ h session for themselves, and wherever available, their partner. Fathers were expected to be involved in the impending child’s upbringing but not required to be in a relationship with the mother. Sessions were conducted in their home when possible for participant convenience unless the participant expressed a preference for a lab session or there was insufficient space for completion of the protocol in their home. Private separate rooms were required to ensure that mothers engage in the protocol apart from their partner. All measures were administered electronically on laptop computers and completed with headphones. Participants (mother and father separately) were compensated with a $60 gift card. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all procedures in the longitudinal study.

Measures

Measures for each model component are described below; internal consistencies appear in Table 1 for mothers and fathers separately.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and sample internal consistencies for measures for mothers and fathers

| Mothers |

Fathers |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | α | Mean | SD | α | |

| PCA Attitudes | ||||||

| Physical abuse vignettes Definition | 5.57 | 1.54 | .57 | 5.41 | 1.58 | .62 |

| Physical abuse vignettes Severity | 24.14 | 3.54 | .64 | 23.17 | 4.25 | .75 |

| Physical abuse vignettes Reporting | 4.77 | 1.48 | .55 | 4.54 | 1.68 | .68 |

| AAPI Corporal Punishment scale | 31.84 | 8.29 | .82 | 32.27 | 9.04 | .83 |

| Parent-CAAM Task | 19.17 | 11.76 | .81 | 18.69 | 12.61 | .84 |

| Empathy | ||||||

| IRI Empathic Concern | 29.14 | 4.28 | .70 | 26.90 | 4.62 | .72 |

| IRI Perspective Taking | 26.57 | 4.75 | .76 | 26.27 | 4.64 | .74 |

| Reactivity | ||||||

| Frustration Discomfort Scale | 17.94 | 5.25 | .82 | 17.70 | 5.74 | .86 |

| Negative Mood Regulation Scale | 64.59 | 16.69 | .90 | 63.46 | 17.05 | .91 |

| PASATa | 84.45 | 68.40 | 90.19 | 71.10 | ||

| Attributions | ||||||

| Plotkin Vignettes Attribution total | 39.88 | 16.27 | .85 | 38.54 | 17.31 | .88 |

| Video Rating Negative Attribution | 3.58 | .44 | .84 | 3.55 | .42 | .80 |

| Infant Cry Questionnaire Minimization | 2.32 | .62 | .75 | 2.43 | .73 | .82 |

| Infant Cry Questionnaire Spoil | 2.49 | .83 | .75 | 2.58 | .91 | .80 |

| Noncompliance IAT D-scorea | 1.05 | .40 | 1.02 | .49 | ||

| Expectations | ||||||

| Compliance Expectations | 17.43 | 3.69 | .70 | 17.75 | 3.67 | .74 |

| Knowledge | ||||||

| Knowledge Discipline alternativesa | .83 | .23 | .79 | .27 | ||

| Taxes | ||||||

| Brief Symptom Index | 9.76 | 8.89 | .88 | 5.05 | 6.72 | .89 |

| SAMISS substance use | 1.66 | 2.33 | .67 | 4.77 | 3.65 | .72 |

| CTS-2 Victimizationa | 6.63 | 11.75 | 4.74 | 7.58 | ||

| Resources | ||||||

| Coping Self Efficacy | 97.49 | 21.98 | .92 | 104.46 | 20.23 | .90 |

| SSRI Social Satisfaction | 41.56 | 7.34 | .91 | 41.05 | 7.56 | .92 |

| Couple Satisfaction | 50.25 | 12.86 | .98 | 52.82 | 8.89 | .95 |

| PCA risk | ||||||

| Child Abuse Potential Inventorya | 95.69 | 74.82 | 86.05 | 58.05 | ||

| Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory | 101.95 | 18.57 | .87 | 107.61 | 20.00 | .89 |

| ReACCT Noncompliance | .09 | 12.89 | .76 | .19 | 12.95 | .76 |

| ReACCT Compliance | −7.72 | 9.14 | .83 | −7.41 | 9.18 | .81 |

| Expected Authoritarian Parenting | 34.20 | 6.58 | .80 | 34.31 | 6.91 | .83 |

AAPI Adult–Adolescent Parenting Inventory, IRI Interpersonal Reactivity Index, PASAT Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task, CTS Conflict Tactics Scale, ReACCT Response Analog to Child Compliance Task

Alpha not computed: PASAT and IAT are single values, Knowledge of Discipline is a proportion score, CTS-2 involves low frequency count data, the Child Abuse Potential Inventory items are variably weighted

Taxes

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis and Melisaratos 1983) is a frequently used measure of current mental health symptoms. Participants report on the frequency of experiencing 18 symptoms of depression and anxiety, rated from (0) Not at all to (4) Extremely, for the past 7 days.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Illness Scale (SAMISS; Whetten et al. 2005) is a screener that includes seven items inquiring about substance use. Items assess alcohol and illicit drug use, assessing both frequency and extent of problematic use, in which higher scores indicate greater use.

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2; Straus et al. 1996) is a widely used measure of intimate partner violence. Of the 20 items that inquire about the frequency of perpetration and victimization in the past year, this study used the 8 items reflecting experience of physical assault (CTS-2 Victimization scale).

Resources

The Social Support Resources Index (SSRI; Vaux and Harrison 1985) scale was utilized to assess social support. Using a 5-point scale, participants report on their satisfaction with each of their two closest supporters (five items for each supporter). Higher ratings reflect greater satisfaction.

The Couple Satisfaction Index (CSI; Funk and Rogge 2007) is an inventory assessing partner relationship satisfaction. Ten items were selected on which participants responded on a 6-point scale, with higher summed scores indicative of greater relationship satisfaction.

The Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES; Chesney et al. 2006) assessed participants’ sense of adequate coping. Twelve items are rated on a 11-point scale, from (0) cannot do at all to (10) certain I can do. Summed across the items, higher total scores reflect greater sense of effective coping skill.

PCA Attitudes

The Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory-2 (AAPI; Bavolek and Keene 2001), Form A (an alternate version than used for PCA Risk below), contains a Value of Corporal Punishment scale, with 11 items assessing parents’ endorsement of physical discipline. Parents respond on a 5-point scale, from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree, with higher scores reflecting greater physical discipline support.

The Physical Abuse Vignettes (PAV; Shanalingigwa 2009) present eight vignettes illustrating a wide range of PCA intensity, from hitting a child without bruising through to burning with a cigarette. Parents respond to: (1) whether they view the parental response as maltreatment (Yes/No), summed across vignettes for a Definition score; (2) how serious they rate the parental behavior on a 4-point Likert scale, for a Severity score; and (3) whether they would report the situation to child protective services (Yes/No), summed for a Reporting scale. On all three scales, higher scores indicate less acceptance of PCA.

The Parent–Child Aggression Acceptability Movie Task (Parent-CAAM Task; Rodriguez et al. 2011) is an analog task designed to implicitly determine attitudes toward PCA, involving eight 90-s movie clips with varying levels of PCA (five physical abuse, three physical discipline). Respondents stop the video if and when they believe the scene has become physically abusive based only on the scene depicted. Scores are determined from the number of milliseconds until the parent stops the video. Time spent in considering a socially desirable response would delay response time. Thus, slower response time in finding a scene abusive is considered to demonstrate greater acceptability of PCA.

Empathy

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis 1983) assesses dispositional empathic ability, with two subscales selected for this study: Empathic Concern, the ability to affectively sympathize, and Perspective Taking, the ability to adopt the psychological perspective of others. Each subscale includes seven items rated from (1) does not describe me well to (5) describes me very well. Scores for subscales are summed across items, with higher total scores reflecting greater empathy.

Reactivity

The Negative Mood Regulation Scale (NMRS; Catanzaro and Mearns 1990) includes 30 items assessing emotion regulation focused on the ability to restore emotional balance after experiencing distress. Participants respond on a 5-point scale from (1) strongly agree to (5) strongly disagree. Scores were oriented such that higher scores reflect poorer emotion regulation ability.

The Frustration Discomfort Scale (FDS; Harrington 2005) contains 7 items reflecting tolerance of discomfort and frustration. Items are rated on a 5-point scale from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Summed total scores are oriented such that higher scores indicate poorer frustration tolerance.

A computerized Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT; Schloss and Haaga 2011) is a cognitive test that can be structured as an implicit measure of frustration tolerance. Participants are presented a series of numbers one at a time for 3.5 s, adding each new number to the previous number. Then they must ignore that sum and add a new number to the previous number. Incorrect or slow sums trigger an aversive sound blast. After several practice trials, participants are presented with 172 trials (10 min) unless they opt to select the large “QUIT” button to discontinue. Scores are the number of trials attempted.

Negative Child Attributions

The Plotkin Child Vignettes (PCV; Plotkin 1983) evaluate perceptions of intentional misbehavior in 18 vignettes. Participants select how much they believe the depicted child intentionally annoyed the parent on a 9-point scale, from (1) did not mean to annoy me at all to (9) the only reason the child did this was to annoy me, where higher scores suggest more negative attributions.

The Infant Crying Questionnaire (ICQ; Haltigan et al. 2012) is a measure in which parents indicate what they believe about infant crying and what they want to achieve when their infant cries. The ICQ contains 43 items rated on a 5-point scale from (1) never to (5) always. Two subscales were selected for this study: the Minimization scale (nine items that view crying as manipulation or nuisance), and the Spoil scale (three items where the parent believes responding to crying spoils the baby); higher scores on both scales indicate more negative crying attributions.

The Video Ratings (VR; Leerkes and Siepak 2006) involve two 1-min videos depicting babies crying while playing with a toy. After each video, 18 questions are presented on which participants rate their attributions for the baby crying on a 4-point scale. One subscale was selected for this study, the Negative Internal Attributions scale (six items each video, involving perception of the baby as spoiled or unreasonable). Higher total scores, summed across videos, indicate less negative crying attributions.

The Noncompliance Implicit Association Test (N-IAT; Rabbitt 2013) is an analog task modeled after the original IAT (Greenwald et al. 1998). Participants are asked to categorize words describing child behavior (e.g., “tantrum”) into good/bad or obeying/disobeying. Speeded sorting is expected when participants see a word consistent with their underlying attributional belief. Through several randomized trials, a difference score is generated, where higher D scores suggest more negative attributions.

Compliance Expectations

The Compliance Expectations measure was designed for this study given the absence of alternative measures for this SIP stage. Based on similar vignette approaches (e.g., Rodriguez and Sutherland 1999), vignettes were selected that varied on two dimensions: perceived child culpability (accidental vs. intentional) and intensity of parental physical reaction (none, low, and moderate), yielding six categories. After pilot testing 30 vignettes with 62 adults, six scenes (one from each category) were selected near the midpoint on a scale of (1) learned their lesson to (5) will do it again. In this study, parents indicated whether they expected the child in the vignette to repeat similar behavior after the depicted parent’s discipline response (4 physical responses, 2 non-physical responses) using this same scale. Lower scores thus indicate expectations of greater future compliance.

Knowledge of Discipline Alternatives

Similar to a coding strategy utilized in Ateah and Durrant (2005), after the final PCV vignette, parents generated all possible discipline responses they would administer if the depicted child was theirs. Two independent raters categorized each separate response, resulting in a total number of responses in one of three categories: physical discipline response (e.g., spanking or hitting with an object); non-physical discipline response (e.g., time-out, removal of privileges, reasoning, presentation of an aversive consequence); or psychological response (e.g., yelling, threatening, swearing, calling names; further details on this measure available upon request). The two counts from the raters were averaged and scores were generated to reflect the proportion of non-physical responses identified relative to their total number of responses, thereby controlling for those participants who provided a larger total number of discipline options. Interrater reliability was strong between raters for the number of non-physical options (ICC = .94) and the total options provided (ICC = .94).

PCA Risk Dependent Variables

The Child Abuse Potential Inventory (CAPI; Milner 1986) is the most widely recognized measure to screen for abuse risk, with 160 Agree/Disagree items. Of these, only 77 are variably weighted for the Abuse Scale, with factors of Distress, Rigidity, Unhappiness, Problems with Child and Self, Problems with Family, and Problems with Others (but the items do not address parenting). Prior studies have demonstrated good predictive validity (Milner 1994). Higher CAPI Abuse Scale scores indicate greater abuse risk.

The Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory-2 (AAPI; Bavolek and Keene 2001) Form B served as an additional measure of abuse potential which has been used in protective services, assessing the beliefs and behaviors regarding child-rearing characteristic of abusive parenting. Forty items are rated on a 5-point scale from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Summed total scores were oriented such that higher scores suggest greater abuse risk.

An Expected Parental Authority Questionnaire (E-PAQ) is a parenting style measure modified from the original (Buri 1991) to present the 30 items in future tense, asking expectant parents how they expect to raise their impending child. Although three parenting styles are assessed, expected Authoritarian parenting was selected for this study, with higher scores oriented to indicate more authoritarian parenting.

The Response Analog to Child Compliance Task (ReACCT; Rodriguez 2016) is a computerized simulation of a realistic parent–child interaction in which they are running late to get their child to preschool. Parents are asked to provide responses to child compliance and non-compliance. In 12 scenes, the parent provides an instruction in which the child is either compliant or noncompliant. Throughout, the participant hears and sees a ticking clock to simulate time urgency and receives a game bonus of 50 cents if they secure quick compliance. Participants select from 16 response options, some of which are adaptive (receiving positive weights) versus maladaptive (receiving negative weights). Scores of interest are parents’ responses for Noncompliance and Compliance, where higher scores indicate harsher responses.

Data Analyses

Analyses were conducted with SPSS 23.0 and Mplus 7.4, using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. Three sets of path models were estimated: one for all mothers, one for all fathers, and a dyadic model incorporating couples to enable direct mother-father comparisons. Dyadic path models account for the nesting of mothers and fathers within the same family (Peugh et al. 2013; Wendorf 2002).

Data reduction was accomplished by creating composite scores. Based on a confirmatory factor analysis, all selected variables loaded significantly onto their respective factors. Composite scores were thus created by standardizing each variable (separately for mothers and fathers) within a factor and averaging those standardized scores (except Knowledge of Discipline and Compliance Expectations were single scores). Composites were comprised of the following scores: PCA Attitudes (PAV Definition, Reporting, and Severity scores; AAPI Corporal Punishment Scale; Parent-CAAM); Empathy (IRI Empathic Concern and Perspective Taking); Reactivity (FDS, PASAT, NMRS); Attributions (PCV Attribution; VR Negative Attribution; ICQ Minimization and Spoil; N-IAT); Taxes (BSI, CTS-2 Victimization, SAMISS); Resources (CSES, SSRI Satisfaction, CSI); PCA Risk (CAPI Abuse Scale; AAPI-2; ReACCT Noncompliance and ReACCT Compliance; Expected PAQ Authoritarian).

Results

Participant means and standard deviations are displayed in Table 1. The obtained sample mean CAPI Abuse Scale and AAPI-2 Total scores are within normal limits. Although not the focus of our research questions, correlations between measures for both mothers and fathers appear in Table 2 for reader interest.

Table 2.

Correlations between measures for mothers and fathers

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PAV-Defn | .65*** | .62*** | −.57*** | −.41*** | .02 | −.02 | −.02 | .02 | .03 | −.08 | .19* | −.04 | −.10 | |

| 2. PAV-Sev | .46*** | .65*** | −.37*** | −.35*** | .02 | −.08 | −.10 | .09 | .01 | −.07 | .18* | −.03 | −.12 | |

| 3. PAV - Report | .56*** | .70*** | −.33*** | −.47*** | −.07 | −.10 | −.03 | .20* | −.08 | −.02 | .10 | .09 | −.08 | |

| 4. AAPI-Corp | −.33*** | −.16* | −.28*** | .32*** | .02 | −.04 | .02 | −.05 | −.07 | .14 | −.19* | .12 | .20* | |

| 5. Parent-CAAM | −.22** | −.25*** | −.22** | .20** | −.02 | .01 | .04 | −.10 | −.01 | .07 | −.12 | .00 | .09 | |

| 6. IRI-EmpConc | .15* | .02 | .04 | −.16* | −.07 | .57*** | −.08 | −.29*** | .32*** | −.07 | .30*** | −.31*** | −.29*** | |

| 7. IRI-PerspTak | .21** | .15* | .19** | −.18** | −.11 | .55*** | −.16 | −.23** | .22** | −.23** | .30*** | −.32*** | −.30*** | |

| 8. FDS | −.16* | −.15* | −.16* | .12 | .16* | −.29*** | −.28*** | .36*** | −.01 | .04 | −.17* | .22** | .13 | |

| 9. NMRS | −.11 | −.08 | −.03 | .15* | .14* | −.42*** | −.33*** | .43*** | −.17* | .05 | −.21* | .44*** | .21** | |

| 10. PASAT | .02 | −.09 | −.03 | −.08 | .02 | .22** | .09 | −.16* | −.12 | −.06 | .14 | .20* | .13 | |

| 11. PCV | −.17* | −.08 | −.14* | .33*** | .16* | −.15* | −.13 | .19** | .03 | −.18* | −.20* | .18* | .15 | |

| 12. VR-NegAttr | .24*** | .01 | .01 | −.23*** | −.20** | .44*** | .20** | −.29*** | −.27*** | .20** | −.34*** | −.38*** | −.34*** | |

| 13. ICQ-Min | −.19** | −.01 | −.12 | .17* | .07 | −.33**** | −.31*** | .34*** | .33*** | −.23*** | .17* | −.28*** | .60*** | |

| 14. ICQ-Spoil | −.22** | −.12 | −.15* | .21** | .17* | −.25*** | −.20** | .24*** | .25*** | −.14* | .23** | −.40*** | .46*** | |

| 15. N-IAT | .02 | −.06 | −.10 | −.07 | −.18* | .20** | .12 | −.15* | −.20** | .17* | .00 | .30*** | −.18* | −.10 |

| 16. ComplExp | .10 | −.13 | −.12 | −.20** | .11 | −.03 | −.17* | .02 | .07 | .17* | −.25*** | .12 | .01 | −.04 |

| 17. KnowDisc | .05 | .05 | .07 | −.40*** | −.02 | .00 | .07 | −.15* | −.11 | .15* | −.14* | .13 | −.04 | −.13 |

| 18. BSI | −.05 | .00 | −.01 | .06 | .01 | .03 | −.05 | .17* | .25*** | −.05 | .19** | −.02 | .12 | .08 |

| 19. SAMISS | .03 | −.17* | −.16* | .02 | .14* | .04 | −.07 | .14* | .10 | .03 | .18* | .05 | .11 | .19** |

| 20. CTS-2 | −.13 | −.09 | −.10 | .07 | .18* | −.01 | −.12 | .09 | .11 | −.09 | .20** | −.08 | .16* | .12 |

| 21. CSES | .11 | .08 | .07 | −.09 | −.18* | .29*** | −.40*** | −.28*** | −.52*** | .00 | −.10 | .28*** | −.28*** | −.19** |

| 22. SSRI-Satisf | .09 | .03 | −.01 | −.02 | −.10 | .28*** | .25*** | −.22*** | −.32*** | .15* | .09 | .30*** | −.25*** | −.17* |

| 23. CSI | .18* | .04 | .03 | −.09 | −.21** | .00 | .08 | −.10 | −.12 | .13 | −.26*** | .21** | −.09 | −.14* |

| 24. CAPI | −.09 | .08 | .10 | .10 | .05 | −.13 | −.13 | .27*** | .32*** | −.29*** | .27*** | −.24*** | .28*** | .24** |

| 25. AAPI-2 | −.42*** | −.09 | −.19** | .53*** | .24*** | −.31*** | −.19** | .25*** | .22*** | −.42*** | .51*** | −.47*** | .34*** | .43*** |

| 26. ReACCT-Non | −.32*** | −.09 | −.14* | .50*** | .20** | −.22** | −.22** | .07 | .07 | −.25*** | .41*** | −.33*** | .21** | .23*** |

| 27. ReACCT-Com | −.11 | .08 | .05 | .09 | .19* | −.17* | −.13 | .10 | .17* | −.17* | .19** | −.30*** | .21** | .19** |

| 28. E-PAQ | −.13 | −.03 | −.14* | .48*** | .14* | −.01 | .04 | .13 | −.03 | −.28*** | .26*** | −.16* | .18* | .22** |

| 15. | 16. | 17. | 18. | 19. | 20. | 21. | 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | 28. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PAV-Defn | −.06 | .24** | .33*** | .06 | −.03 | −.09 | .09 | .01 | .07 | −.07 | −.42*** | −.40*** | .03 | −.36*** |

| 2. PAV-Sev | −.02 | .06 | .24** | .02 | −.06 | −.06 | .08 | .08 | .06 | −.11 | −.24** | −.27*** | .12 | −.27*** |

| 3. PAV - Report | −.18* | .09 | .24* | .04 | −.04 | −.12 | .04 | .03 | .04 | −.03 | −.17* | −.15 | .18* | −.24*** |

| 4. AAPI-Corp | −.02 | −.19* | −.49* | −.09* | −.08 | .12 | .02 | .14 | −.07 | .06 | .57*** | .53*** | .05 | .60*** |

| 5. Parent-CAAM | .08 | −.23** | −.15 | −.05 | .01 | .05 | −.03 | .01 | .03 | .02 | .28*** | .14 | .07 | .30*** |

| 6. IRI-EmpConc | .26*** | −.08 | −.13 | −.12 | −.14 | −.30*** | .21* | .28*** | .09 | −.25** | −.18* | −.08 | −.25** | .11 |

| 7. IRI-PerspTak | .15 | −.15 | −.01 | −.16* | −.08 | −.21** | −.22** | .23*** | −.01 | −.19* | −.14 | −.11 | −.20* | −.04 |

| 8. FDS | −.18* | .03 | .13 | .07 | .13 | .02 | −.36*** | −.25** | −.10 | .20* | .09 | .02 | .15 | −.04 |

| 9. NMRS | −.38*** | .22** | .14 | .12 | .04 | .04 | −.52*** | −.29*** | −.22** | .39*** | .20* | .08 | .35*** | −.14 |

| 10. PASAT | .31*** | .14 | −.02 | −.04 | .05 | −.13 | .10 | .22** | .07 | −.24** | −.24** | −.22** | −.32*** | −.14 |

| 11. PCV | −.07 | −.23** | −.22** | .26** | .09 | .21* | −.12 | −.14 | −.18* | .24** | .21* | .10 | .20* | .24** |

| 12. VR-NegAttr | .20* | .04 | −.00 | −.18* | −.07 | −.33*** | .34** | .24** | .24** | −.39*** | −.30*** | −.23** | −.21* | −.09 |

| 13. ICQ-Min | −.40*** | −.02 | .02 | .21* | .09 | .13 | −.18* | −.14 | −.14 | .39*** | .46*** | .19 | .27*** | .08 |

| 14. ICQ-Spoil | −.28*** | .02 | −.00 | .18* | .11 | .21* | −.03 | −.11 | −.06 | .29*** | .41*** | .15 | .20* | .17* |

| 15. N-IAT | .01 | −.03 | .10 | −.08 | −.07 | .11 | .19* | .15 | −.23** | −.29*** | −.09 | .32*** | −.00 | |

| 16. ComplExp | .06 | .06 | .01 | .09 | .05 | −.07 | .02 | .02 | −.11 | −.38*** | −.18* | −.14 | −.37*** | |

| 17. KnowDisc | .10 | .05 | −.11 | −.08 | −.18* | −.05 | −.11 | .11 | .02 | −.21** | −.30*** | −.04 | −.31*** | |

| 18. BSI | .05 | .09 | .11 | .25*** | .30*** | −.29*** | −.22** | −.26*** | .43*** | .02 | −.12 | .18* | −.04 | |

| 19. SAMISS | .10 | .11 | .09 | .28*** | .28*** | .01 | −.14 | −.33*** | .17* | −.09 | −.06 | .08 | −.15 | |

| 20. CTS-2 | .03 | .14 | .01 | .43*** | .34*** | −.14 | −.18* | −.42*** | .26** | .18* | .08 | .10 | −.03 | |

| 21. CSES | .22** | −.10 | .03 | −.28*** | −.18** | −.17* | .59*** | .32*** | −.51*** | −.12 | −.04 | −.29*** | .08 | |

| 22. SSRI-Satisf | .22** | −.05 | .14* | −.26*** | −.14* | −.23*** | .45*** | .43*** | −.49*** | −.09 | .03 | −.34*** | .05 | |

| 23. CSI | .11 | −.04 | .13 | −.30*** | −.12 | −.35*** | .17* | .44*** | −.46*** | −.18* | −.11 | −.21** | −.02 | |

| 24. CAPI | −.19** | −.08 | −.15* | .61*** | .19** | .41*** | −.34*** | −.45*** | −.54*** | .37*** | .22** | .42*** | .17* | |

| 25. AAPI-2 | −.23*** | −.27*** | −.23*** | .14* | −.04 | .18** | −.16* | −.18* | −.25*** | .43*** | .52*** | .29*** | .57*** | |

| 26. ReACCT-Non | −.11 | −.18** | −.39*** | .10 | .00 | .20** | −.06 | −.22** | −.25*** | .29*** | .53*** | .27*** | .45*** | |

| 27. ReACCT-Com | −.14* | −.12 | −.13 | .05 | −.12 | .06 | −.14* | −.17& | −.14 | .22** | .34*** | .43*** | .20* | |

| 28. E-PAQ | −.10 | −.23*** | −.19** | .04 | .06 | .10 | .08 | −.03 | −.09 | .24*** | .48*** | .25*** | .13 |

Below the diagonal, mothers; above the diagonal, fathers. 1 = Physical Abuse Vignettes (PAV) Definition; 2 = PAV Severity; 3 = PAV Reporting; 4 = Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory (AAPI) Corporal Punishment; 5 = Parent-Child Aggression Acceptability Movie Task; 6 = Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) Empathic Concern; 7 = IRI Perspective Taking; 8 = Frustration Discomfort Scale; 9 = Negative Mood Regulation Scale; 10 = Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task; 11 = Plotkin Vignettes Attribution Total; 12 = Video Rating Negative Attribution; 13 = Infant Cry Questionnaire (ICQ) Minimization; 14 = ICQ Spoil; 15 = Noncompliance Implicit Association Test; 16 = Compliance Expectations; 17 = Knowledge of Discipline Alternatives; 18 = Brief Symptom Inventory; 19 = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Screener; 20 = Conflict Tactics Scale-2 Victimization; 21 = Coping Self-Efficacy; 22 = Social Satisfaction; 23 = Couple Satisfaction Index; 24 = Child Abuse Potential Inventory Abuse Scale; 25 = AAPI-2; 26 = Response Analog to Child Compliance Task (ReACCT) Intentional Noncompliance Total; 27 = ReACCT Compliance Total; 28 = PAQ Expected Authoritarian Parenting

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

We ran preliminary models to identify important variables to covary in predicting PCA risk (see Little 2013). These models sought to identify which demographic variables significantly predicted PCA risk but were not substantially collinear with another. Based on these models, we included age and educational level as covariates. These factors were significantly related to PCA risk for mothers, fathers, or both, and they were sufficiently independent of each other. For mothers, higher PCA risk was significantly associated with lower education level (β = −.30, p <.001) and lower age (β = −.29, p < .001). For fathers, higher PCA risk was significantly associated with lower education level (β = −.43, p < .001) and marginally associated with lower age (β = −.17, p = .061). Path models were estimated with and without demographic covariates of PCA risk. However, including demographic covariates did not reduce any significant paths to non-significance or alter the pattern presented in the figures.

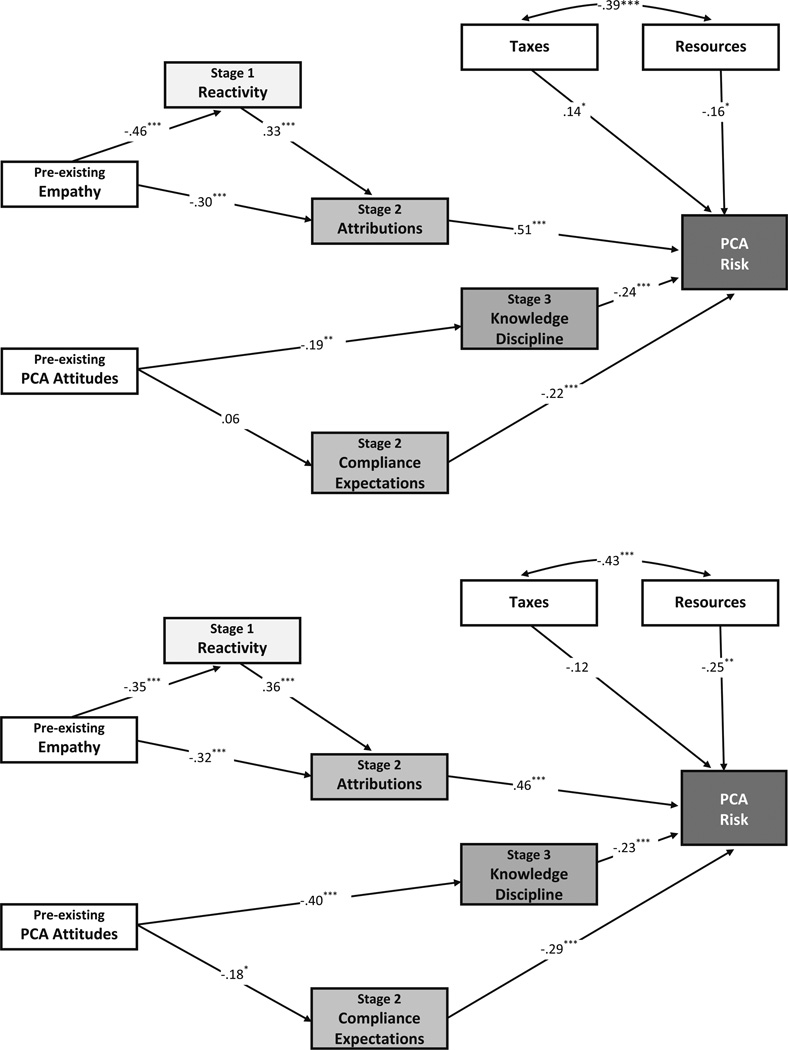

Mothers’ PCA Risk

For mothers, the path model is displayed in the top portion of Fig. 1. Lower empathy scores significantly predicted greater reactivity (β = −.46, p < .001) and more negative attributions (β = −.30, p < .001), and greater reactivity in turn predicted more negative child attributions (β = .33, p <.001). Higher PCA approval attitudes significantly predicted less knowledge of discipline alternatives (β = −.19, p = .005) but not child compliance expectations (β = .06, p = .376). Greater PCA risk, in turn, was significantly predicted by more negative attributions (β = .51, p < .001), less knowledge of discipline alternatives (β = −.24, p < .001), higher compliance expectations (β = −.22, p < .001), higher taxes (β = .14, p < .05), and fewer personal resources (β = −.16, p < .05). The model R2 for PCA risk was 42.7 %. Adding the demographic predictors increased R2 only slightly (44.3 %) and thus the figure displays the path model without covariates.

Fig. 1.

Path models for expectant mothers (top) and fathers (bottom)

* p < .05, ** p <.01, *** p < .001

Note: lower compliance expectations = expecting more compliance

Father’s PCA Risk

For fathers, the path model is displayed at the bottom of Fig. 1. Poorer empathy significantly predicted greater reactivity (β = −.35, p < .001) and more negative child attributions (β = −.32, p < .001), and greater reactivity in turn predicted more negative attributions (β = .36, p < .001). Attitudes favoring PCA significantly predicted less knowledge of non-physical discipline alternatives (β = −.40, p < .001) as well as higher compliance expectations (β = −.18, p < .05). Elevated PCA risk, in turn, was significantly predicted by higher negative child attributions (β = .46, p < .001), less knowledge of discipline alternatives (β = −.23, p < .001), higher compliance expectations (β = −.29, p <.001), and fewer resources (β = −.25, p <.001) but not personal vulnerabilities that represented taxes (β = −.12, p = .182). The model R2 for PCA risk was 40.4 %. Adding the demographic predictors increased R2 only slightly (43.3 %).

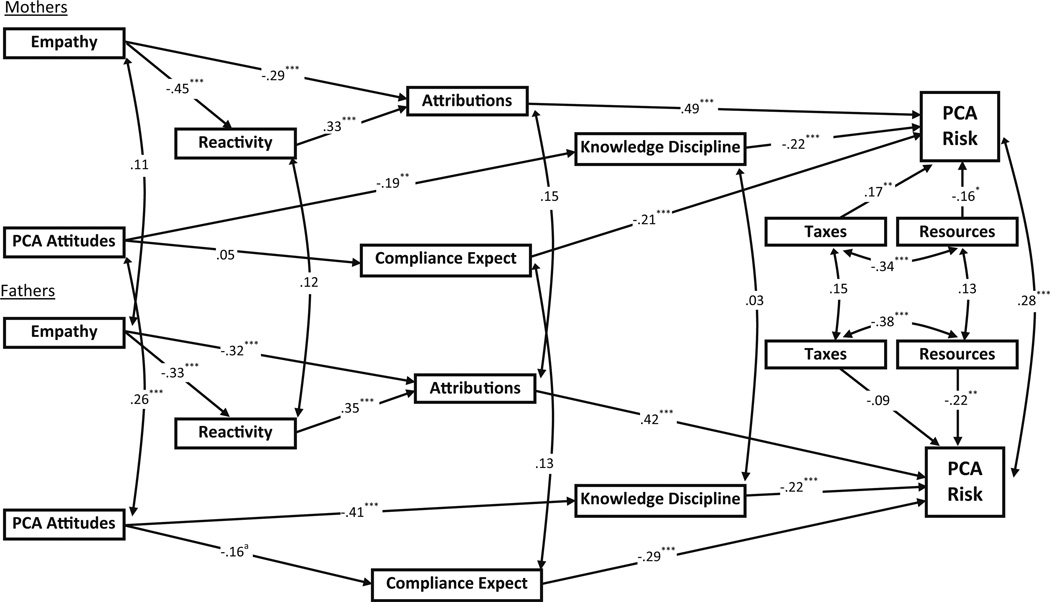

Dyadic PCA Risk

Our final model was a dyadic model that included both members of a couple in the model simultaneously, permitting direct comparisons. The dyadic path model thus estimates the effects for mothers and fathers in light of their nesting within the same couple and thus greater-than-chance resemblance (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Dyadic SIP path model with standardized coefficients

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001; amarginal, p = 06

Note: lower compliance expectations = expecting more compliance

For mothers, lower empathy significantly predicted greater reactivity (β = −.45, p < 001) and more negative child attributions (β = −.29, p <001), and greater reactivity in turn predicted more negative attributions (β = .33, p < .001). More favorable PCA Attitudes significantly predicted less knowledge of discipline alternatives (β = −.19, p = .005) but not compliance expectations (β = .05, p = .452). Higher PCA risk, in turn, was significantly predicted by more negative attributions (β = .49, p <.001), less knowledge of discipline alternatives (β = −.22, p < .001), higher compliance expectations (β = −.21, p < .001), higher taxes (β = .17, p = .010), and fewer resources (β = −.16, p = .017).

For fathers, poorer empathy significantly predicted greater reactivity (β = −.33, p < .001), although significantly less than observed for mothers (β = −.45, 95 % CI [−.35, −.55]). Poorer empathy also significantly predicted more negative child attributions (β = −.32, p < .001), and greater reactivity in turn predicted negative attributions (β = .35, p < .001). Attitudes approving of PCA significantly predicted less knowledge of discipline alternatives among fathers (β = −.41, p < .001), significantly more than its role for mothers (β = −.19, 95 % CI [−.08, −.30]). Fathers’ greater approval of PCA marginally predicted expecting more compliance from children (β = −.16, p = .060), playing a somewhat larger role than observed in mothers (β = .05, 95 % CI [−.06, .17]). Heightened PCA risk, in turn, was significantly predicted by more negative child attributions (β = .42, p < .001), less knowledge of discipline alternatives (β = −.22, < .001), higher expectations of compliance (β = −.29, p < .001), and fewer resources (β = −.22, p = .001). However, fathers’ greater PCA risk was not significantly predicted by more personal taxes (β = −.09, p = .300), a notable difference from mothers (β = .17, 95 % CI [.06, .27]).

The dyadic model found essentially similar effects as the individual models for mothers and fathers. The dyadic model R2 for PCA risk was 39.6 % for mothers and 35.9 % for fathers. Adding demographic covariates increased R2 slightly (40.9 % for mothers, 39.5 % fathers).

Discussion

This study evaluated the role of parents’ SIP processes in conjunction with personal vulnerabilities and resiliencies in relation to PCA risk. Furthermore, the study sought to predict PCA risk for first-time mothers and their partners using a multimethod approach. Vulnerabilities, such as psychopathology, substance abuse, and domestic violence, were expected to predict increased PCA risk, whereas personal resources such as social support, partner satisfaction, and coping ability, were expected to predict lower PCA risk. The SIP model considered in this study proposed specific pathways wherein parents utilize pre-existing cognitive and affective schema that relate to different cognitive processes. The findings provide partial support for these predictions, evidencing commonalities and distinctions between mothers and fathers.

In this study, poor empathy was conceptualized as a preexisting affective quality that was anticipated to be associated with more intense reactivity compromising attentional processes in SIP Stage 1 which were both expected to shape more negative child attributions in Stage 2. Such attributions were then expected to be associated with elevated abuse risk. Indeed, this pattern was observed for both mothers and fathers. Parents who are not as empathic appear more likely to overreact, displaying poor mood regulation and greater frustration as well as developing more negative child attributions. Low empathy has been implicated in increased abuse risk (e.g., Perez-Albeniz and de Paul 2004) and poor emotion regulation has been observed in mothers frustrated by infant crying (Russell and Lincoln 2016). Negative child attributions have previously been associated with PCA risk (e.g., Berlin et al. 2013; Haskett et al. 2006). The current study links overreactivity and attributions to dispositional empathy for both mothers and fathers, although low empathy was not as strongly related to overreactivity for fathers. Thus, our findings suggest empathy may operate differently in leading to increased PCA risk between mothers and fathers. Clearly more research on the role of empathy in fathers is needed to determine whether this is a suitable prevention target.

In a separate pathway, attitudes approving of PCA were expected to predict less knowledge of non-physical discipline alternatives and higher expectations of child compliance following discipline, which would each in turn relate to increased PCA risk. This pathway was notably disparate between mothers and fathers. Although less knowledge of non-physical discipline alternatives and higher compliance expectations were observed to increase PCA risk for both mothers and fathers, the connections to PCA approval were distinct. Attitudes approving of PCA were only related to fathers’ higher compliance expectations, not mothers. Moreover, fathers that approve of PCA also appear less aware of non-physical approaches to disciplining their child significantly more than mothers’ who approve PCA. Preexisting attitudes approving of parent–child aggression have previously been associated with child abuse risk (e.g., Bower-Russa et al. 2001; Rodriguez et al. 2011). But minimal research has considered the role of PCA attitudes among fathers nor how parents’ PCA attitudes relate to their compliance expectations or awareness of options. Both of these factors appear important avenues for further inquiry.

Apart from SIP processes, parents’ taxes and resources were also considered in this model. Although both predicted mothers’ PCA risk, such personal vulnerabilities did not predict fathers’ PCA risk. Prior research has investigated personal vulnerabilities in elevating PCA risk among mothers, but fathers are often neglected in this area (see Stith et al. 2009 for review). Further research should explore the role of taxes on fathers’ more inclusively. We assessed three potential personal vulnerabilities (psychopathology, substance use, and domestic violence victimization) which can affect a parent’s personal life independent of parenting. Future studies should consider alternative personal vulnerabilities relevant to fathers that may serve to compromise their fathering.

Notably, surprisingly limited work on PCA risk has investigated parents’ resiliency, instead concentrating primarily on vulnerabilities. The current study affirmed the role of coping, social support, and partner satisfaction as resources related to lower PCA risk for both mothers and fathers. Consequently, PCA prevention efforts that strive to curtail risks should also promote parents’ resiliencies to accomplish the same ultimate aim—a reduction in PCA.

Overall, however, the findings echo existing literature that fathers’ risk profiles are broadly comparable to mothers (e.g., Rodriguez et al. 2016; Schaeffer et al. 2005; Smith Slep and O’Leary 2007), with minor distinctions. Our inclusion of fathers in predicting PCA risk adds to the literature by offering direct comparisons of maternal and paternal PCA risk. Although fathers are implicated in approximately half of those engaging in physical maltreatment (Sedlak et al. 2010), the literature remains tentative about factors that influence paternal child abuse risk. Continued investigation into the array of factors germane to paternal risk remains a high priority in the field.

This study evidences several noteworthy strengths and limitations. This study presents findings from a single wave of the Triple-F study, a cross-sectional design such that causal interpretations should be avoided. Indeed, although the SIP model implies a sequence of processing, even longitudinal models cannot assess aspects of these stages in real time within a discipline episode given how automatically schemas may be processed. The present cross-sectional analysis clarifies which elements may account for greater PCA risk as potential intervention targets. The sample diversity is a strength that enhances generalizability, although few parents identified as Hispanic/Latino, representing a group requiring more study. This study included a comprehensive set of predictors, including several personal resources which are often overlooked in this field. Larger sample sizes could permit greater model complexity and more nuanced statistical analyses, including moderation effects. Future research should consider similar, inclusive models that incorporate additional vulnerabilities, resiliencies, and preexisting affect states (e.g., anger) or other SIP factors (e.g., SIP Stage 3 beliefs about mitigating information accounting for the child’s behavior). Refining SIP processes with specific paths can provide clearer guidance to inform prevention and intervention programs. Participants in this study were also not yet parents; to understand the evolution of PCA risk and the factors that influence parenting behavior, a longitudinal design is warranted to determine how selected processes, risks, and resiliencies unfold over time to impact PCA trajectories in the transition to parenthood.

This study provides insights into areas to enhance in parenting interventions designed to abate child abuse risk. Enriched home-visiting programs have proven effective, for example, in modifying attributions (Bugental et al. 2002), which could perhaps also add instruction on reasonable expectations regarding future child compliance following discipline. Given the results of this study, strategies that promote empathic affect or that modify the preexisting attitudes approving of parent–child aggression should also prove beneficial. Continued efforts to promote parenting skills by teaching knowledge of non-physical discipline alternatives could be coupled with encouragement of parents to access their resources to combat their taxes. Furthermore, programs could facilitate emotion regulation skills training available for first-time mothers and their partners. More broadly, media campaigns could reach a wider audience, serving as an outlet for disseminating techniques of alternative discipline practices (e.g., Barlow and Calam 2011). In sum, this study informs prevention and intervention programs, grounded in theory, with precise areas on which to concentrate for both mothers and fathers.

Acknowledgments

We thank our participating families and participating Obstetrics/Gynecology clinics that facilitated recruitment. This research was supported by award number R15HD071431 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval As indicated in the methods, all procedures performed adhered to ethical standards and was approved by the Institutional Review Board

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

- Ammerman RT, Altaye M, Putnam FW, Teeters AR, Zou Y, Ginkel JB. Depression improvement and parenting in low-income mothers in home visiting. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2014;18:555–563. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0479-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman RT, Kolko DJ, Kirisci L, Blackson TC, Dawes MA. Child abuse potential in parents with histories of substance use disorder. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1999;23:1225–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman RT, Patz RJ. Determinants of child abuse potential: Contribution of parent and child factors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:300–307. [Google Scholar]

- Ateah CA, Durrant JE. Maternal use of physical punishment in response to child misbehavior: Implications for child abuse prevention. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29:169–185. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Calam R. A public health approach to safeguarding in the 21st century. Child Abuse Review. 2011;20:238–255. [Google Scholar]

- Bavolek SJ, Keene RG. Adult–Adolescent Parenting Inventory (AAPI-2): Administration and development handbook. Park City, UT: Family Development Resources Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Etiology of child maltreatment: A developmental-ecological analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:413–434. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Reznick JS. Examining pregnant women’s hostile attributions about infants as a predictor of offspring maltreatment. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:549–553. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DA, Heyman RE, Smith Slep AM. Risk factors for child physical abuse. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6:121–188. [Google Scholar]

- Bower-Russa ME, Knutson JF, Winebarger A. Disciplinary history, adult disciplinary attitudes, and risk for abusive parenting. Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:219–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Ellerson PC, Lin EK, Rainey B, Kokotovic A, O’Hara N. A cognitive approach to child abuse prevention. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:243–258. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buri JR. Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Assessment. 1991;57:110–119. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanueva CE, Martin SL. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and mothers’ child abuse potential. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:603–622. doi: 10.1177/0886260506298836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro SJ, Mearns J. Measuring generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation: Initial scale development and implications. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;54:546–563. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman SA. Validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11:421–437. doi: 10.1348/135910705X53155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilamkurti C, Milner JS. Perceptions and evaluations of child transgressions and disciplinary techniques in high- and low-risk mothers and their children. Child Development. 1993;64:1801–1814. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb04214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch JL, Behl LE. Relationships among parental beliefs in corporal punishment, reported stress, and physical child abuse potential. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2001;25:413–419. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. The effects of dispositional empathy on emotional reactions and helping: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality. 1983;51:167–184. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Reid JB, Knutson JF. Direct laboratory observations and analog measures in research definitions of child maltreatment. In: Feerick M, Knutson JF, Trickett P, Flanzier S, editors. Child abuse and neglect: Definitions, classifications, and a framework for research. Baltimore, MD: Brooks; 2006. pp. 293–328. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE, Trocme N, Fallon B, Milne C, Black T. Protection of children from physical maltreatment in Canada: An evaluation of the Supreme Court’s definition. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma. 2009;18:64–87. [Google Scholar]

- Eid M, Deiner E. Handbook of multimethod measurement in psychology. Washington, DC: APA; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH, Olson MA. Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and use. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:297–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Sumida E, McCann C, Winstanley M, Fukui R, Seefeldt T, et al. The transition to parenthood among young African American and Latino couples: Relational predictors of risk for parental dysfunction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:65–79. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.17.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk JL, Rogge RD. Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:572–583. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. More harm than good: A summary of the scientific research on the intended and unintended effects of corporal punishment on children. Law and Contemporary Problems. 2010;73:31–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano AM. Why we should study subabusive violence against children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1994;9:412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald RL, Bank L, Reid JB, Knutson JF. A discipline-mediated model of excessively punitive parenting. Aggressive Behavior. 1997;23:259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JKL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1464–1480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltigan JD, Leerkes EL, Burney RV, O’Brien M, Supple AJ, Calkins SD. The infant crying questionnaire: Initial factor structure and validation. Infant Behavior and Development. 2012;35:876–883. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington N. The frustration discomfort scale: Development and psychometric properties. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2005;12:374–387. [Google Scholar]

- Haskett ME, Scott SS, Fann KD. Child abuse potential inventory and parenting behavior: Relationships with high-risk correlates. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1995;19:1483–1495. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskett ME, Scott SS, Willoughby M, Ahern L, Nears K. The parent opinion questionnaire and child vignettes for use with abusive parents: Assessment of psychometric properties. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21:137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hien D, Cohen LR, Caldeira NA, Flom P, Wasserman G. Depression and anger as risk factors underlying the relationship between substance involvement and child abuse potential. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MA, Price RL, Marrs DW. Linking theory construction and theory testing: Models with multiple indicators and latent variables. Academy of Management Review. 1986;11:128–144. [Google Scholar]

- Kadushin A, Martin JA. Interview study of abuse-event interaction. In: Kadushin A, editor. Child abuse: An interactional event. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1981. pp. 141–224. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Bellamy JL, Guterman NB. Fathers, physical child abuse, and neglect: Advancing the knowledge base. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:227–231. doi: 10.1177/1077559509339388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Grogan-Kaylor A, Berger LM. Parental spanking of 1-year-old children and subsequent child protective services involvement. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2014;38:875–883. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EL, Siepak K. Attachment linked predictors of women’s emotional and cognitive responses to infant distress. Attachment and Human Development. 2006;8:11–32. doi: 10.1080/14616730600594450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Lindenberger U, Nesselroade JR. On selecting indicators for multivariate measurement and modeling with latent variables: When “good” indicators are bad and “bad” indicators are good. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:192–211. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, Medina AM, Oliver PH. The co-occurrence of husband-to-wife aggression, family-of-origin aggression, and child abuse potential in a community sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:413–440. [Google Scholar]

- McElroy EM, Rodriguez CM. Mothers of children with externalizing behavior problems: Cognitive risk factors for abuse potential and discipline style and practices. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008;32:774–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennen FE, Trickett PK. Parenting attitudes, family environments, depression, and anxiety in caregivers of maltreated children. Family Relations. 2011;60:259–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS. The child abuse potential inventory: Manual. 2nd. Webster, NC: Psyctec; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS. Assessing physical child abuse risk: The child abuse potential inventory. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14:547–583. [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS. Social information processing and child physical abuse: Theory and research. In: Hansen DJ, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation, Vo. 46, 1998: Motivation and child maltreatment. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2000. pp. 39–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS, Dopke C. Child physical abuse: Review of offender characteristics. In: Wolfe DA, McMahon RJ, Peters RD, editors. Child abuse: New directions in prevention and treatment across the lifespan. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Montes MP, de Paul J, Milner JS. Evaluations, attributions, affect, and disciplinary choices in mothers at high and low risk for child physical abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2001;25:1015–1036. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT) 2016 Retrieved from https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=8367126&icde=0.

- Nosek BA. Understanding the individual implicitly and explicitly. International Journal of Psychology. 2007;42:184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Albeniz A, De Paul J. Gender differences in empathy in parents at high- and low-risk of child physical abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peugh JL, DiLillo D, Panuzio J. Analyzing mixed-dyadic data using structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2013;20:314–337. [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin R. Cognitive mediation in disciplinary actions among mothers who have abused or neglected their children: Dispositional and environmental factors. University of Rochester; 1983. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Price-Wolff J. Social support, collective efficacy, and child physical abuse: Does parent gender matter? Child Maltreatment. 2015;20:125–135. doi: 10.1177/1077559514562606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz R, Sanders M, Shapiro C, Whitaker D, Lutzker J. Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P System Population Trial. Prevention Science. 2009;10:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0123-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitt SM. The role of stress in parental perceptions of child noncompliance. Yale University; 2013. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D, Hammock G, Smith S, Gardner W, Signo M. Empathy as a cognitive inhibitor of interpersonal aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 1994;20:275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM. Parent-child aggression: Association with child abuse potential and parenting styles. Violence and Victims. 2010a;25:728–741. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM. Personal contextual characteristics and cognitions: Predicting child abuse potential and disciplinary style. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010b;25:315–335. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM. Analog of parental empathy: Association with physical child abuse risk and punishment intentions. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2013;37:493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM. Parental discipline reactions to child noncompliance and compliance: Association with parent-child aggression indicators. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25:1363–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Bower-Russa M, Harmon N. Assessing abuse risk beyond self-report: Analog task of acceptability of parent-child aggression. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2011;35:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Richardson MJ. Stress and anger as contextual factors and pre-existing cognitive schemas: Predicting parental child maltreatment risk. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:325–337. doi: 10.1177/1077559507305993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Russa MB, Kircher JC. Analog assessment of frustration tolerance: Association with self-reported child abuse risk and physiological reactivity. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2015;46:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Smith TL, Silvia PJ. Multimethod prediction of physical parent-child aggression risk in expectant mothers and fathers with social information processing theory. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2016;51:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Sutherland D. Predictors of parents’ physical disciplinary practices. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1999;23:651–657. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Tucker MC. Predicting physical child abuse risk beyond mental distress and social support: Additive role of cognitive processes. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24:1780–1790. [Google Scholar]

- Russell BS, Lincoln CR. Distress tolerance and emotion regulation: Promoting maternal well-being across the transition to parenthood. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2016;16:22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer CM, Alexander PC, Bethke K, Kretz LS. Predictors of child abuse potential among military parents: Comparing mothers and fathers. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20:123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Schloss HM, Haaga DAF. Interrelating behavioral measures of distress tolerance with self-reported experiential avoidance. Journal of Rational-Emotive Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. 2011;29:53–63. doi: 10.1007/s10942-011-0127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, Li S. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, Executive Summary. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/nis4_report_congress_full_pdf_jan2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Shanalingigwa OA. Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota. Dissertation Abstracts International; 2009. Understanding social and cultural differences in perceiving child maltreatment. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Slep AM, O’Leary SG. Multivariate models of mothers’ and fathers’ aggression toward their children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:739–751. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Liu T, Davies C, Boykin EL, Alder MC, Harris JM, et al. Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. New evidence for the benefits of never spanking. Society. 2001;38:52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Child Maltreatment 2014. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- Vaux A, Harrison D. Support network characteristics associated with support satisfaction and perceived support. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1985;13:245–268. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid J. Adapting the Incredible Years, an evidence-based parenting programme, for families involved in the child welfare system. Journal of Children’s Services. 2010;5:25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wendorf CA. Comparisons of structural equation modeling and hierarchical linear modeling approaches to couples’ data. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Reif S, Swartz M, Stevens R, Ostermann J, Hanisch L, Eron JJ., Jr A brief mental health and substance abuse screener for persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2005;19:89–99. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipple EE, Richey CA. Crossing the line from physical discipline to child abuse: How much is too much? Child Abuse and Neglect. 1997;5:431–444. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]