Abstract

Stress might be one of the most salient intrinsic factors influencing the risk of stroke and its outcome. Previous studies have linked stress to increased infarct size and exaggerated cognitive deficits in rodent models of stroke. This study compares the effects of chronic restraint stress, representing a psychological stressor, prior to or after motor cortex devascularization lesion on motor recovery in rats. Daily testing in a skilled reaching task revealed initially exaggerated deficits in limb use caused by pre-lesion stress in the absence of increased infarct size. Both pre- and post-lesion stresses affected movement by delaying recovery and limiting compensation of lesion-induced deficits. Nevertheless, only rats that experienced post-lesion stress showed enlarged infarct size. This was accompanied by enlarged edema formation in the lesion hemisphere of post-stress animals on day 2 post-lesion. There were no significant differences in infarct size between post-lesion day 2 and day 15. The data demonstrate that both pre- and post-lesion chronic restraint stresses affect motor recovery after ischemic lesion. Lesion volume, however, is influenced by the timing of a stressful experience relative to the lesion. These findings suggest that stress represents a critical variable determining the outcome after stroke.

Keywords: Ischemia, Restraint stress, Skilled reaching, Recovery, Edema, Infarct size

1. Introduction

A common consequence of ischemic stroke is motor disability affecting the upper limbs (Cirstea and Levin, 2000; Krakauer, 2005). Although some spontaneous recovery usually occurs, most patients suffer from residual impairments in skilled limb use. One major influence of the degree of recovery after a stroke might be stress. Clinical studies have shown that high levels of the stress hormone cortisol shortly after a stroke are predictive of poor functional outcome and high morbidity (Murros et al., 1993; Christensen et al., 2004). Additionally, May et al. (2002) found that psychological distress is a predictor of fatal stroke in humans. It is therefore possible that stress experienced prior to a stroke or stress caused by functional loss after the stroke is a critical factor in the course of recovery of individual patients.

The limited number of animal studies investigating the influence of stress on recovery from stroke has focused on cognitive function and infarct volume. Stress can increase cognitive deficits along with infarct size after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in mice (DeVries et al., 2001; Sugo et al., 2002). Moreover, chronic multiple stress after 2-vein occlusion increases cell death within the hippocampus of rats (Ritchie et al., 2004). Studies focusing on lesion size found that the time point and duration at which stress occurs is a major determinant of the outcome. For instance, Madrigal et al. (2003) showed that acute pre-lesion restraint stress increases infarct size, while chronic restraint stress reduces infarct size. Manipulation of circulating stress hormone levels confirms the role of stress in recovery from stroke. Pre-treatment with the corticosteroid synthesis inhibitor metyrapone acts neuro-protectively when given after MCAO in rats (Smith-Swintosky et al., 1997; Krugers et al., 1998, 2000). In contrast, Risedal et al. (1999) found that pre-lesion treatment with metyrapone did not influence infarct size, while post-lesion administration exacerbated infarct volume and motor deficits in rats. It is therefore likely that the time window of stress, either prior to or after the lesion, exerts differential effects on initial motor deficits and the course of recovery.

The present study compares the effects of pre-lesion versus post-lesion stress on recovery of skilled forelimb function, lesion size and edema formation in a rat model of ischemic stroke. In Experiment 1, pre-trained animals received a devascularization lesion of motor cortex and were then continuously tested in the single pellet reaching task. The development of lesion size was investigated in a subset of animals at 2 and 15 days post-lesion. Experiment 2 examined the effects of stress before versus after devascularization on edema formation as a possible mechanism of stress-induced modulation of stroke outcome. Edema formation was suggested to be influenced by stress hormones (Abraham et al., 1992) and positively related to infarct size (Slivka et al., 1995). It was hypothesized that post-lesion stress will cause exacerbated lesion size and behavioural deficits in comparison to pre-lesion stress.

2. Results

2.1. Lesion size

Three brains from 2 day post-lesion [one CONTROL (n=5) and two PRE-STRESS (n=4)] were removed from analysis due to damage from brain extraction. The infarct area included the primary and secondary motor cortex, and forelimb and hind limb areas of the somatosensory cortex. On a few occasions the corpus callosum on the lesion side was severed. Fig. 1 illustrates series of sections through representative brains from a CONTROL animal, day 2 and day 15 PRE-STRESS, and day 2 and day 15 POST-STRESS animals. In the POST-STRESS group, the area of infarct often included the dorsolateral striatum and cingulate cortex, which was not found in CONTROL animals. A significant overall difference in lesion volume was found (F(5,33)=4.623, p≤0.001). As shown in Fig. 2, lesion sizes in the POST-STRESS group on 2 days after lesion were larger than those of CONTROL animals at the same time point (t=−2.28, p≤0.05). On day 15 after lesion, lesions in the POST-STRESS group were significantly larger than lesions at 2 days (p≤0.05, Scheffe) and 15 days post-lesion (p≤0.05, Scheffe) in the CONTROL group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Serial sections comparing the lesion extend in representative CONTROL, PRE-LESION and POST-LESION rats. The area of infarct included the dorsolateral striatum and cingulate cortex only in the POST-STRESS group.

Fig. 2.

Volume of tissue lost after devascularization lesion of the motor cortex on post-lesion day 2 and 15. On days 2 and 15 post-lesion the POST-STRESS animals showed a significantly larger lesion volume than CONTROL animals. Asterisksindicate significances compared to controls: *p≤0.05 (Scheffe's test).

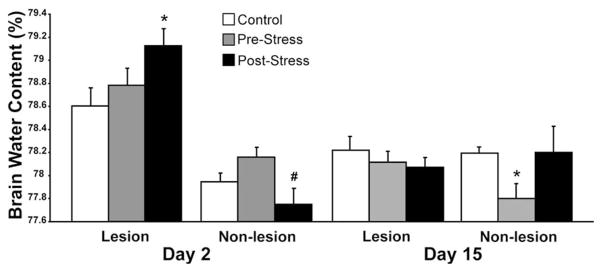

2.2. Brain water content

On 2 days post-lesion there were significant differences in water content between the lesion and non-lesion hemispheres in the POST-STRESS (t=3.107, p≤0.05), PRE-STRESS (t=10.019, p≤0.001), and CONTROL (t=10.453, p≤0.001) groups on 2 days post-lesion (Fig. 3). On 15 days post-lesion, there were no differences between lesion and non-lesion hemispheres in any of the groups. In the lesion hemisphere, POST-STRESS animals showed larger edema formation than CONTROL rats(t=−2.37,p≤0.05) on day 2. Furthermore, brain water content in the non-lesion hemisphere was reduced in POST-STRESS animals when compared to PRE-STRESS treatment on day 2 after lesion (t=2.39, p≤0.05. On day 15, PRE-STRESS treatment reduced edema formation (t=2.44, p≤0.05).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of brain water content (edema) after devascularization lesion on Day 2 and Day 15 post-lesion in the lesion and non-lesion hemispheres. Note that post-stress treatment increased edema formation in the lesion hemisphere on day 2, but had no effect on edema on day 15. Asterisks indicate significances between groups: *p≤0.05 (t-test compared to CONTROL rats), #p≤0.01 (PRE-STRESS versus POST-STRESS data).

2.3. Glucose and corticosterone levels

There were no differences in blood glucose levels between groups. There was a significant overall group difference in corticosterone levels (F(2,34)=5.520, p≤0.01). The PRE-STRESS (p ≤0.05, Scheffe) and the POST-STRESS (p≤0.01, Scheffe) groups had significantly higher corticosterone levels at baseline than the CONTROL group. There were no differences between the PRE-STRESS and POST-STRESS groups at baseline. On 15 days pre-lesion, PRE-STRESS animals had significantly higher corticosterone levels than CONTROL rats (p≤0.05, Scheffe). There was no significant difference in corticosterone levels in the CONTROL and POST-STRESS groups, or the PRE-STRESS and POST-STRESS groups. On 15 days post-lesion, POST-STRESS animals had significantly higher corticosterone than CONTROL (p≤0.001, Scheffe) and PRE-STRESS (p≤0.01, Scheffe) animals. There was no significant difference between the CONTROL and PRE-STRESS groups.

There was also a significant effect of Group and Time (F(4,34)=5.769, p≤0.001). While corticosterone levels of CONTROL and PRE-STRESS groups did not change over time, levels of the POST-LESION group did (F(2,12)=15.472, p≤0.001). In the POST-STRESS group there was no significant change in corticosterone levels from baseline to pre-lesion sampling, however, there was a significant increase in corticosterone levels from pre-lesion to post-lesion blood sampling.

2.4. Single pellet reaching performance

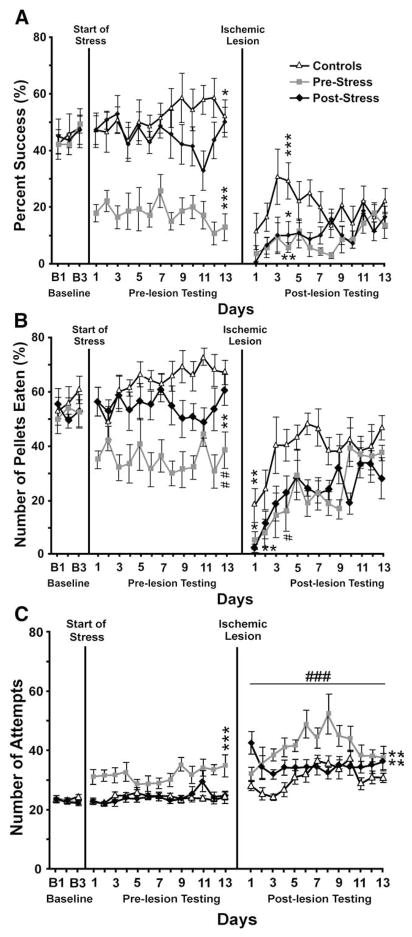

2.4.1. Reaching success

One rat from each group was eliminated from statistical analysis due to difficulty to meet the training criteria (at least 40% baseline reaching success). No significant difference between the groups in percent success was noted during baseline sessions. There was a significant difference between the groups during pre-lesion testing (F(2,18)=16.680, p≤0.001). The PRE-STRESS group had significantly lower reaching success compared to the CONTROL (p≤0.001, Scheffe) and the POST-STRESS (p≤0.01, Scheffe) groups. There was no significant difference between the CONTROL and POST-STRESS groups. After the lesion, there was a drop in reaching success in all groups. There was a significant overall difference between groups during post-lesion testing (F(2,18)=4.894, p≤0.05). Moreover, PRE-STRESS animals had significantly lower success rates than CONTROL animals (p≤0.05, Scheffe). There was no significant difference between the CONTROL and POST-STRESS groups during post-lesion testing though there was a trend towards significance. No significant difference was noted between the PRE-STRESS and POST-STRESS groups during post-lesion testing (see Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of success rate (A) and of pellets eaten (B) and number of reaching attempts (C) in the single pellet reaching task. There were no significant differences between the groups during baseline testing. During pre-lesion stress, the PRE-STRESS group had significantly lower success rates and ate fewer pellets than the CONTROL and POST-STRESS groups. Following the lesion, success rates in all groups were reduced as compared to the pre-lesion period. PRE-STRESS animals had overall reduced reaching success, ate fewer pellets and made more reaching attempts compared to CONTROL rats. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, compared to previous test period (t-test). #p≤0.05, compared to CONTROL rats (Scheffe's test).

Within-group comparisons revealed that the CONTROL group showed improvement during pre-lesion testing when compared to baseline (t=−2.925, p≤0.05). Post-lesion success rates of CONTROL rats then dropped when compared to pre-lesion testing (t =9.470, p ≤0.001). In contrast, pre-lesion success rates in PRE-STRESS rats dropped when compared to baseline (t=8.327, p≤0.001). Furthermore, success rates in PRE-STRESS animals dropped further post-lesion when compared to pre-lesion testing (t=3.645, p≤0.05). While the POST-STRESS group maintained reaching success during baseline and pre-lesion testings, their success showed a significant decline during post-lesion testing (t=6.502, p≤0.01).

There was no significant correlation between success rates and lesion volume on day 14 post-lesion in the CONTROL (R=−0.679, p=0.093), PRE-STRESS (R=−0.372, p=0.411), and the POST-STRESS (R=0.519, p=0.232) groups or when the groups were combined (R=−0.424, p=0.055).

2.4.2. Number of pellets eaten

There were no significant differences in the percentage of total pellets eaten during baseline testing. There was a significant effect of percentage of pellets eaten during pre-lesion testing (F(2,18)=14.07, p≤0.001) and a Group-Time effect (F(2,24)= 1.593, p≤0.05). Post-hoc analysis revealed that at pre-lesion testing the PRE-STRESS group ate significantly fewer pellets than the CONTROL (p ≤0.001) and POST-STRESS (p ≤0.01) groups. Further analysis revealed that during the first week of pre-lesion testing the PRE-STRESS rats were significantly impaired compared to the CONTROL (p≤0.01) and POST-STRESS (p≤0.01) groups. During the second week of pre-lesion stress, however, the PRE-STRESS rats were only significantly impaired compared to the CONTROL group (p≤0.001), but showed a trend towards significant impairments compared to the POST-STRESS group. There were significant group differences during post-lesion testing (F(2,18)=6.210, p≤0.01).

The POST-STRESS (p≤0.05) and PRE-STRESS (p≤0.05) groups ate significantly fewer pellets than the CONTROL group during post-lesion testing (see Fig. 4B). There was also a Group-Time effect (F(2,24)=3.430, p≤0.001). During the first week of post-lesion testing there was a significant difference between the groups (F(2,20)=8.208, p≤0.01). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the CONTROL group ate significantly more pellets than the PRE-STRESS (p≤0.01, Scheffe) and POST-STRESS (p≤0.05, Scheffe) groups. There was no significant group difference in the number of pellets eaten during the second week of post-lesion testing.

Within-group analysis of the CONTROL group revealed no significant difference in the number of pellets eaten from baseline to pre-lesion testing. There was a significant decrease in the number of pellets the CONTROL group ate after the lesion in comparison to pre-lesion testing (t=7.487, p≤0.001). In the PRE-STRESS group, there was a significant decline in the number of pellets eaten during the pre-lesion testing period in comparison to baseline testing (t=3.913, p≤0.01), which was further diminished during the post-lesion period (t=3.524, p≤0.05). In the POST-STRESS group there was no significant difference in number of pellets eaten from baseline to pre-lesion testing. There was, however, a significant decline from pre-lesion testing to post-lesion testing (t=4.468, p≤0.01).

There was no correlation between lesion volume and number of pellets eaten at 14 days post-lesion in the CONTROL (R=−0.388, p=0.390), PRE-STRESS (R=0.587, p=0.166), and POST-STRESS (R=−0.035, p=0.940) groups, or when groups were examined together (R=0.192, p=0.403).

2.4.3. Number of attempts

There were no significant differences in the number of attempts between the three groups at the end of baseline testing. There was a significant difference between the groups at pre-lesion (F(2,18)=18, p≤0.001) and post-lesion testings (F(2,15)=17.43, p≤0.001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the PRE-STRESS group overall performed more reaching attempts than the CONTROL (p≤0.001) and the POST-STRESS (p≤0.001) groups. In addition, PRE-STRESS rats performed more attempts post-lesion than the CONTROL (p≤0.001) and POST-STRESS (p≤0.05) groups (Fig. 4C). There was a trend for the POST-STRESS group to reach more often than the CONTROL group during post-lesion testing. There was also a Group-Time effect during post-lesion testing (F(2,24)= 2.019, p≤0.01). Further analysis revealed a significant difference between the groups during the first week of post-lesion testing (F(2,20)=13.671, p≤0.001). Post-hoc analysis found that the PRE-STRESS group performed more attempts than the CONTROL group (p≤0.001, Scheffe). There was also a significant difference between the groups during the second week of post-lesion testing (F(2,20)=5.666, p≤0.05). Further analysis also revealed that during the last 6 days of post-lesion testing, PRE-STRESS rats performed significantly more attempts than CONTROL rats (p≤0.05, Scheffe).

Within-group comparisons revealed no significant difference in the number of reaching attempts from baseline to pre-lesion testing in the CONTROL group. The CONTROL group did show an increase in reaching attempts during post-lesion testing compared to pre-lesion testing (t=−5.005, p≤0.01). The PRE-STRESS group showed a significant increase in the number of reaching attempts during pre-lesion testing compared to baseline (t= −7.530, p≤0.001), and during post-lesion testing compared to pre-lesion testing (t=−6.075, p≤0.01). There was no significant difference in the number of attempts made in the POST-STRESS group from baseline to pre-lesion testing, however, there was a significant increase in attempts noted during post-lesion testing in comparison to pre-lesion testing (t=−5.501, p≤0.01).

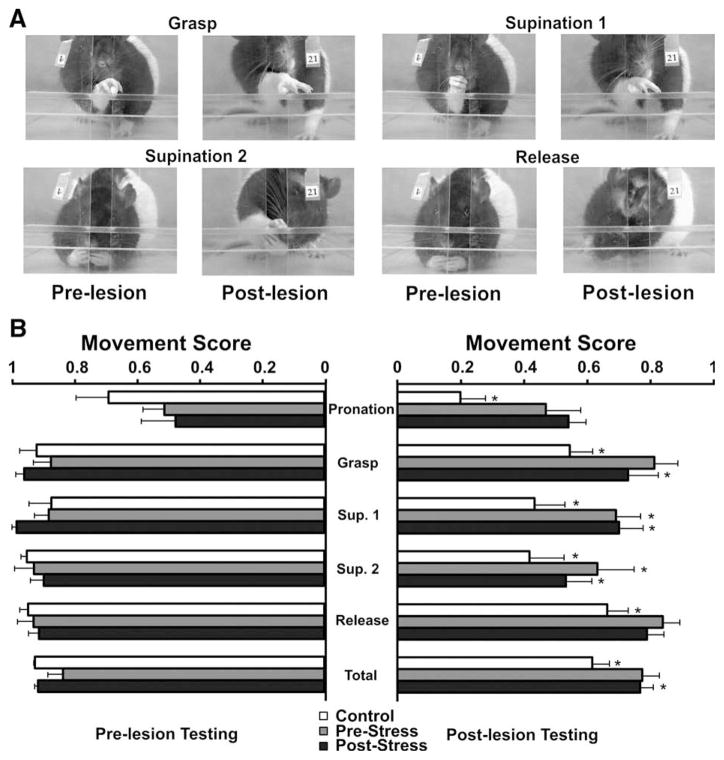

2.4.4. Qualitative reaching analysis

Fig. 5A illustrates a series of photographs depicting pre-lesion and post-lesion reaching movement performances. Both lesion and stress caused characteristic alterations in reaching movement patterns. As described earlier (Whishaw, 2000), the devascularization lesion caused mainly impairments in movement components requiring rotatory limb movements. In the movement analysis, there were no differences in any of the movement components of reaching or in the total score between the groups at baseline or pre-lesion testing (Fig. 5B). During post-lesion testing, there was a significant difference between the groups in digits open (H=6.508, p≤0.05, Kruskal–Wallis Test), with PRE-STRESS rats having a significantly lower score than POST-STRESS rats (Z=−2.402, p≤0.05). Comparisons of the reaching components in the CONTROL group between pre-lesion stress to 14 days post-lesion revealed deficits in limb lift (Z=−1.992, p≤0.05), advance (Z=−2.028, p≤0.05), digits open (Z=−2.201, p≤0.05), pronation (Z=−2.366, p≤0.05), grasp (Z=−2.201, p≤0.05), supination 1 (Z=−2.201, p≤0.05), supination 2 (Z=−2.201, p≤0.05), and release (Z=−2.028, p≤0.05), and there was a significant drop in the total score (Z=−2.366, p≤0.05). In addition, digits close and aim were approaching significance. Comparisons of the reaching components in the PRE-STRESS group from pre-lesion stress to 14 days post-lesion revealed deficits in supination 1 (Z=−2.201, p≤0.05), and supination 2 (Z=−2.023, p≤0.05). Comparisons of the reaching components in the POST-STRESS group from pre-lesion stress to 14 days post-lesion revealed deficits in grasp (Z=−2.023, p≤0.05), supination 1 (Z=−2.023, p≤0.05), supination 2 (Z=−2.201, p≤0.05), and the total score (Z=−1.992, p≤0.05; see Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Qualitative analysis of reaching movements in the single pellet reaching task at 15 days post-lesion. (A) Serial photographs illustrating the grasp, supinations 1 and 2 and release components of a reach. (B) Comparisons of pre-lesion and post-lesion values of pronation, grasp, supination, release and total score. CONTROL rats showed the most impairments in individual components, while the total score was reduced in CONTROL and POST-STRESS rats. Asterisks indicate significances compared to pre-lesion values: *p ≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001 (Kruskal-Wallis test).

3. Discussion

The present study examined the effects of pre-lesion versus post-lesion exposure to restraint stress on motor recovery after motor cortex devascularization lesion in rats. The data show that pre-lesion stress disturbs skilled limb use, including reaching success and number of pellets retrieved and eaten. Post-lesion exposure decreased the number of pellets eaten, and there was a trend towards impaired reaching success and increased number of attempts. Furthermore, post-lesion stress aggravated lesion size in rats, while it also promoted edema formation early after lesion. These findings suggest that stress represents a critical variable to determine the rate of motor recovery and outcome after cerebral injury. The time window of stress exposure has significant influence on motor recovery even in the absence of effects on lesion volume.

3.1. Restraint stress impairs skilled reaching ability and compensatory strategies

The chronic restraint stress regimen used in the present study led to raised levels of circulating corticosterone levels as shown in previous studies (Faraday, 2002; Magarinos and McEwen, 1995). These findings suggest that elevated corticosterone levels can cause changes in skilled forelimb movement prior to (Metz et al., 2001, 2005b) and after devascularization lesion.

The impairments found after motor cortex devascularization of non-stress rats are similar to previous observations, including loss of distal limb control (Whishaw, 2000). Quantitative measures, such as reaching success, usually undergo considerable spontaneous improvement after focal ischemia, which is mainly mediated by the use of compensatory adjustments. These include the replacement of distal limb use with proximal and axial movement (Whishaw, 2000; Metz et al., 2005a; Gharbawie et al., 2005). For example, rats will adjust their posture and will perform exaggerated shoulder and body rotation in order to lift, aim and advance the paw to improve their reaching success (Gharbawie et al., 2005).

The loss of the original movement trajectories and the development of compensatory strategies are reflected by abnormal qualitative scores. Animals modify movement components in order to overcome lesion-induced loss of rotatory limb movements (Whishaw, 2000; Metz et al., 2005a). It is interesting to note that reaching movement patterns were partially preserved in stress-treated groups, although success of reaching movements was not maintained. The preservation of movement scores suggests that the use of compensatory strategies in stress-treated groups was limited. Thus, one can conclude that stress, particularly when present prior to the lesion, alters the ability to develop spontaneous compensatory adjustments early after lesion. This and the reliance upon previously successful strategies may slow the rate of quantitative improvement after lesion.

3.2. Potential mechanism of restraint stress-induced functional impairments

The stress-treated rats' diminished ability to compensate might be causally linked to stress-induced changes in neuronal plasticity. Stress is known to affect neuronal plasticity within the limbic system (Sapolsky, 2003; Sandi, 2004) through mechanisms which most likely also apply to the motor system. A considerable density of glucocorticoid receptors have been found in motor cortex, striatum, and cerebellum (Ahima and Harlan, 1990) suggesting that stress hormones play a role in neuronal function and plasticity of the motor system.

Direct effects of glucocorticoids on the motor system might represent one of the pathways mediating the effects of stress on motor recovery after stroke. Earlier studies provide support for this notion by showing that administration of exogenous glucocorticoids (Sapolsky and Pulsinelli, 1985; Sugo et al., 2002), the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist mifepristone (Risedal et al., 1999; Sugo et al., 2002), or the steroid synthesis inhibitor metyrapone (Smith-Swintosky et al., 1997; Krugers et al., 2000) affects the outcome of ischemic lesions in rodents. The relationship between reaching success, recovery and corticosterone levels in the present study was weak, particularly with regard to group differences found in baseline blood samples. It is possible that a ceiling effect prevented further corticosterone increase in pre- and post-stress-treated animals. This supports an earlier notion that stress might affect motor function and recovery through a route independent of corticosterone (Metz et al., 2005b). Accordingly, Risedal et al. (1999) found that post-lesion treatment with metyrapone after MCAO rather exaggerated deficits in limb placements and the ability to cross a rotating pole. In addition, stress-induced loss of skilled reaching capacity might be linked to persistent emotional changes. Chronic restraint stress represents an animal model of anxiety (Vyas and Chattarji, 2004; Strekalova et al., 2005; Kim and Han, 2006), depression (Strekalova et al., 2005; Kim and Han, 2006) and learned helplessness (Kademian et al., 2005). It is possible that these phenomena hindered the rats' ability to adapt and cope with lesion-induced deficits thus slowing down the rate of functional improvement. Indeed, clinical studies have shown that high levels of anxiety or depression impede functional recovery and represent predictors of poor outcome (Shimoda and Robinson, 1998; Lewis et al., 2001). Nannetti et al. (2005) found that depressed stroke patients started with lower scores on motor abilities, however, patients were still able to recover over time when receiving rehabilitation treatment. Once discharged from the hospital, depressed patients showed slower recovery compared to non-depressed patients (Nannetti et al., 2005). The current study might replicate this finding in rats using skilled limb use. Success of skilled limb use in particular has been shown to be susceptible to anxiety (Metz et al., 2005b) and its lasting effects might account for reduced reaching success in pre-lesion stress animals.

3.3. Post-lesion restraint stress exacerbates infarct size

The present study showed that post-lesion stress increases lesion volume, while pre-lesion stress has no effect. One reason for these findings may be that different durations of exposure to stress prior to ischemic lesion differentially influence infarct size. Accordingly, Madrigal et al. (2003) found that chronic restraint stress for 21 days prior to MCAO decreased infarct volume while seven days of restraint stress increased infarct size. The authors suggested a connection between larger basal glutamate levels, lower ATP availability and increased infarct volume after seven days of pre-lesion restraint stress, which were absent in animals exposed to 21 days of pre-lesion stress (Madrigal et al., 2003).

A notable finding of the present study is the missing correlation between functional recovery, and lesion volume. Although chronic restraint stress prior to lesion had no influence on infarct size, it induced the most severe behavioural deficits in skilled reaching after the lesion. It is likely that these observations are due to the detrimental effects of stress on behavioural and structural plasticity in remaining intact circuits. These circuits might include cortical and subcortical loops involved in the production of skilled reaching movements, such as basal ganglia (Whishaw et al., 1986; Miklyaeva et al., 1994) and red nucleus (Whishaw et al., 1998). Accordingly, lesion-induced neuronal plasticity can occur in regions adjacent and remote to the lesion, including the intact hemisphere (Jones and Schallert, 1992; Jones et al., 1999; Biernaskie and Corbett, 2001). Our finding that post-lesion skilled reaching ability is not correlated to infarct size supports the notion that intact neuronal circuits mediate compensatory movement strategies.

Several mechanisms can account for exaggeration of lesion size in stress-treated animals. Stress can cause the release of glutamate contributing to excitotoxic processes (Madrigal et al., 2003), inducing hyperglycemia (Sapolsky, 1985; Payne et al., 2003) and inhibiting the expression of anti-apoptotic (DeVries et al., 2001) or neurotrophic factors (Adlard and Cotman, 2004). Thus, stress potentially enlarges lesion size or limits plasticity of intact tissue (Scheff et al., 1980; Magarinos and McEwen, 1995). Another possible mechanism of stress-induced cell death may arise from stress-induced hyperthermia (Keeney et al., 2001; Clark et al., 2003), which potentiates cell loss after ischemic injury in rodents (Colbourne et al., 1997; Zaremba, 2004). Furthermore, stress increases blood pressure (Sapolsky et al., 2000), which could particularly amplify bleeding in the infarct site due to ruptured blood vessels in the devascularization lesion model. These effects, however, were limited to the post-lesion stress group.

The present data confirmed our expectations that stress-associated behavioural changes are related to edema formation. In particular post-lesion stress modulated brain water content early after lesion, likely representing vasogenic edema. In spite of these major findings, it is still possible that the present assessments involving the entire hemisphere underestimate the impact of stress on cortical edema formation. The devascularization lesion model may not be the ideal model of stroke for measuring edema as the craniotomy might alleviate some of the increased intracranial pressure. Nevertheless, the craniotomy does not prevent brain swelling into the hole, tissue distortion and the accompanying loss of tissue function. Furthermore, it might be expected that edema formation might have been more severe after a larger lesion size, such as MCAO (Ayata and Ropper, 2002). A larger lesion might provide for a greater potential to significantly influence edema formation. Lastly, it can also be discussed if stress-induced modulation of edema is causally related to glucocorticoids. Treatment with the corticosteroid dexamethasone failed to influence edema formation after stroke in humans (Ito et al., 1980; Ogun and Odusote, 2001). It is therefore possible that stress influences edema formation through a mechanism independently of glucocorticoid receptor activation.

4. Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that chronic restraint stress induces lasting impairments in skilled limb use and compensatory behaviour. Both pre- and post-lesion stresses affect lesion outcome, indicating that chronic stress experienced prior to or after a stroke alters behavioural and neuronal plasticity. These findings suggest that stress might represent a predisposing factor for stroke as well as a critical variable affecting the course of recovery and success of rehabilitative interventions.

5. Experimental procedures

5.1. Animals

Seventy-eight male Long-Evans rats (90 days old and weighing 400–550 g at the beginning of the experiment) raised at the University of Lethbridge vivarium were used in this study. No rats died during the course of the study. The rats were housed in pairs under a 12 h light/day cycle with lights on at 7:30 AM. All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines set by the Canadian Council for Animal Care.

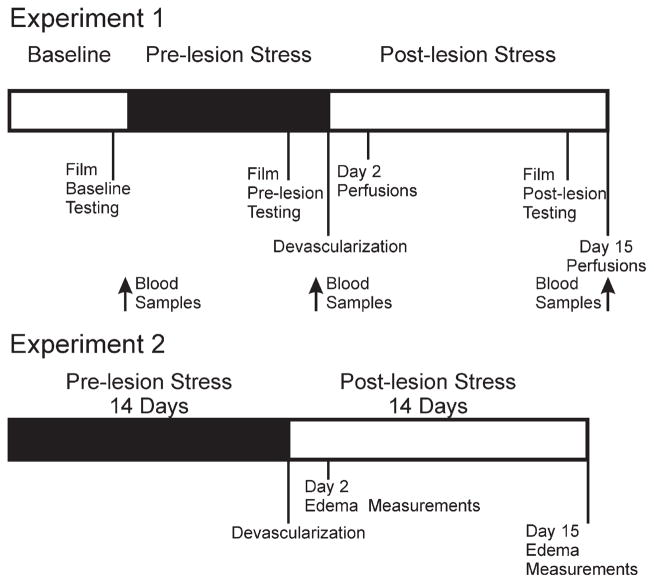

5.2. Experimental design

5.2.1. Experiment 1

The timeline of Experiment 1 is illustrated in Fig. 6 (n=42). Prior to training in the single pellet reaching task, rats were food-deprived to 90–95% of their baseline weight. Rats were trained in the single pellet reaching task until success rates reached an asymptote and were then filmed for baseline performance. Thus, all rats were well acquainted with the skilled reaching task prior to experiencing any stress treatment. The rats were then matched for their reaching success and divided into three groups. The pre-lesion stress group (PRE-STRESS, n=8) underwent restraint stress for 15 days prior to focal ischemia. The post-lesion stress group (POST-STRESS, n=8) was given restraint stress for 15 days after focal ischemia. A control group (CONTROL, n=8) did not undergo restraint stress during the course of the study but was handled every day. During the pre-lesion and post-lesion test periods, animals continued to be tested daily in the single pellet reaching task. On day 14 pre-lesion and day 14 post-lesion, animals were video recorded in the single pellet reaching task. Rats were given one day for recovery after devascularization lesion. Blood samples were collected at baseline and day 15 of pre- and post-lesion intervals.

Fig. 6.

Timelines of Experiment 1 and Experiment 2. PRE-STRESS rats underwent pre-lesion stress for 15 days prior to devascularization lesion and POST-STRESS animals underwent post-lesion stress for 15 days. Only rats from Experiment 1 were tested behaviourally. Rats from each group were perfused on day 2 and day 15 post-lesion for measurement of infarct volume (Experiment 1) and edema formation (Experiment 2).

In addition to the eight animals per group perfused at 15 days post-lesion, six additional animals per group were perfused at 2 days post-lesion for infarct size measurements. These rats also underwent food deprivation and single pellet training prior to the lesion. Rats that survived until 2 days post-lesion underwent restraint stress on both days and were not tested in single pellet reaching. Instead, rats were perfused 30 min after the initiation of restraint stress on day 2 post-lesion. Rats that survived to 15 days post-lesion were perfused following exposure to stress and blood samples.

5.2.2. Experiment 2

Fig. 6 illustrates a timeline of Experiment 2. Rats were randomly divided into three groups. One group underwent 15 days of chronic restraint stress prior to lesion (PRE-STRESS, n=12). One group received chronic restraint stress after lesion (POST-STRESS, n=12) for a maximum of 15 days. Another group underwent a lesion without receiving restraint stress (CONTROL, n=12). Similar to Experiment 1, rats in each group were divided into two survival groups. Edema measurements were taken on 2 days post-lesion (n=6 from each group) and on 15 days post-lesion (n=6 from each group). All the lesions were induced in the left hemisphere. Rats were not trained in the single pellet reaching task in Experiment 2.

5.3. Blood samples

Blood samples were taken 30 min after initiation of restraint stress (Metz et al., 2005b). Rats were individually brought to the surgery suite and rapidly anesthetizedwith isoflurane (4% in 30% oxygen). An average of 0.5 ml of blood was collected from the tail vein of anesthetized rats. Samples were immediately analyzed for glucose levels using a blood glucose meter (Ascensia Breeze, Bayer HealthCare, IN, USA). The remaining sample was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 8 min. The serum was collected and stored at −20 °C. Plasma corticosterone concentrations were determined by radioimmunoassay using commercial kits (Coat-A-Count, Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA). Blood samples were collected on the final day of baseline, on day 15 of pre-lesion stress, and on day 15 of post-lesion stress exposure.

5.4. Focal cerebral ischemia

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (4% induction and 2% maintenance with 30% oxygen). Devascularization lesion of the motor cortex was induced as described by Whishaw (2000). Devascularization lesion was induced on the side contralateral to the paw preferred in reaching (Experiment 1) or sides were randomized (Experiment 2). Briefly, after incising the skin, a craniotomy was made at the following coordinates: −1.0 to 4.0 mm anterior, −1.5 to 4.5 mm lateral. The dura was removed, and the blood vessels were carefully wiped off using a cotton tip. The skin was then sutured and rats were given 0.05 ml of Temgesic (Schering-Plough Inc., Brussels, Belgium).

5.5. Stress regimen

Stress was induced via daily restraint in a transparent Plexiglas tube (6 cm inner diameter and 18 cm long) for 20 min (Metz et al., 2005b). This procedure was performed by an experimenter not involved in behavioural testing. Rats received a break of 10 min before being tested in the single pellet reaching task. Thus, rats were tested 30 min after the induction of restraint stress. In the PRE-STRESS group, rats were given a devascularization lesion 24 h after the last stress treatment. The POST-STRESS group underwent stress 24 h after ischemic injury. Stress occurred during the light cycle between 9:30 AM and 11:30 AM.

5.6. Single pellet reaching task

5.6.1. Quantitative analysis

The reaching box was made of clear Plexiglas as described earlier (Whishaw et al., 1993). Rats were trained to extend their preferred forelimb through a slit in the front wall of the box to grasp and retrieve food pellets (45 mg, Bio Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) located on a shelf outside of the box. Reaching success rates were recorded daily, and at the end of baseline, pre-lesion and post-lesion periods the performance was video recorded for qualitative movement analysis (Metz and Whishaw, 2000). A successful reach was defined as obtaining the pellet on the first attempt, withdrawing the paw and releasing the pellet into the mouth. Analysis included percentage of success, percentage of total number of pellets eaten, and number of reaching attempts to grasp a single pellet (Metz et al., 2005b).

5.6.2. Qualitative analysis

Reaching movements were rated frame-by-frame from video recordings. Ten movement components and 28 subcomponents were analyzed (Metz and Whishaw, 2000). Each of the subcomponents was scored on a 3-point scale: 1 point was given if the movement was present; 0.5 point if the movement was present but abnormal; 0 point if the movement was absent. Scores of three reaches were averaged. The total score was calculated from the ten components.

5.7. Edema measurement

Rats were deeply anesthetized and decapitated. The brains were quickly removed, the hemispheres separated, and wet weight was measured. The brains were then dried in an oven (VWR Scientific Products, Batavia, IL) at 100 °C for 24 h. The dry weights of each hemisphere were measured. Edema levels were determined using the wet/dry method (Ito et al., 1980; MacLellan et al., 2004) and the following formula: Brain water content (%)=[(Wet weight−Dry weight)/wet weight]×100.

5.8. Histology

After behavioural testing was completed, rats were deeply anesthetized and perfused through the heart with 0.9% saline and 4% formaldehyde. Brains were removed and post-fixed overnight before being placed in a 30% sucrose solution. The brains were frozen and 40 μm sections were cut on the cryostat. Every fifth section was mounted onto slides and stained with cresyl violet to calculate lesion volume.

5.9. Measurement of lesion volume

Digital photographs of cresyl violet stained sections from the following ten planes (from bregma) were analyzed: 3.70 mm, 3.20 mm, 2.70 mm, 2.20 mm, 1.70 mm, 1.20 mm, 0.70 mm, 0.20 mm, −0.30 mm, and −0.80 mm. The cross sectional volumes of both hemispheres were calculated using Zeiss Axiovision 4.3 (Zeiss, Germany). Lesion volume was determined according to DeBow et al. (2003) using the following formulas:

5.10. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statview software version 4.5 (SAS Institute, 1998). The data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Scheffe's test was used for post-hoc analysis. Within-group analysis of quantitative data and comparisons between lesion and non-lesion hemispheres were performed via paired t-tests. Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests were used for analysis of qualitative reaching data. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used for within-group comparisons in the qualitative behavioural analysis. Correlation analysis of motor recovery and lesion volume on day 15 post-lesion was performed using Pearson's chi-squared test. In all analysis a p-value of ≤0.05 was chosen as the significance level. All data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Ian Q. Whishaw, Fred Colbourne, and Robert J. McDonald for their helpful discussions. This research was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (GM), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (GM), and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AC, GM).

References

- Abraham C, Koltai M, Joo F, Tosaki A, Szerdahelyi P. Adrenalectomy aggravates ischemic brain edema in female Sprague–Dawley rats with carotid arteries ligated. Prog Brain Res. 1992;91:23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlard PA, Cotman CW. Voluntary exercise protects against stress-induced decreases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein expression. Neuroscience. 2004;124:985–992. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahima RS, Harlan RE. Charting of Type II glucocorticoid receptor-like immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. Neurosciene. 1990;39:579–604. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayata C, Ropper AH. Ischaemic brain oedema. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:113–124. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernaskie J, Corbett D. Enriched rehabilitative training promotes improved forelimb motor function and enhanced dentritic growth after focal ischemic injury. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5272–5280. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05272.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirstea MC, Levin MF. Compensatory strategies for reaching in stroke. Brain. 2000;123:940–953. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.5.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DL, Debow SB, Iseke MD, Colbourne F. Stress-induced fever after postischemic rectal temperature measurements in the gerbil. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81:880–883. doi: 10.1139/y03-083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Boysen G, Johannesen HH. Serum-cortisol reflects severity and mortality in acute stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2004;217:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbourne F, Sutherland G, Corbett D. Postischemic hypothermia. a critical appraisal with implications for clinical treatment. Mol Neurobiol. 1997;14:171–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02740655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AC, Joh HD, Bernard O, Hattori K, Hurn PD, Traystman RJ, Alkayed NJ. Social stress exacerbates stroke outcome by suppressing Bcl-2 expression. PNAS USA. 2001;98:11824–11828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201215298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBow SB, Davies MLA, Clark HL, Colbourne F. Constraint-induced movement therapy and rehabilitation exercises lessen motor deficits and volume of brain injury after striatal hemorrhage stroke in rats. Stroke. 2003;34:1021–1026. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000063374.89732.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraday MM. Rat sex difference in response to stress. Physiol Behav. 2002;75:507–522. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00645-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharbawie OA, Gonzalez CLR, Whishaw IQ. Skilled reaching impairments from the lateral frontal cortex component of middle cerebral artery stroke: a qualitative and quantitative comparison to focal motor cortex lesions in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2005;156:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito U, Ohno K, Suganuma Y, Suzuki K, Inaba Y. Effect of steroid on ischemic brain edema: analysis of cytotoxic and vasogenic edema occurring during ischemia and after restoration of blood flow. Stroke. 1980;2:166–172. doi: 10.1161/01.str.11.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Schallert T. Overgrowth and pruning of dendrites in adult rats recovering from neocortical damage. Brain Res. 1992;581:156–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90356-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Chu CJ, Grande LA, Gregory AD. Motor skills training enhances lesion-induced structural plasticity in the motor cortex of adult rats. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10153–10163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-10153.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kademian SME, Bignante AE, Lardone P, McEwen BS, Volosin M. Biphasic effects of adrenal steroids on learned helplessness behaviour induced by inescapable shock. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;30:58–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney AJ, Hogg S, Marsden CA. Alterations in core body temperature, locomotor activity, and corticosterone following acute and repeated social defeat in male NMRI mice. Physiol Behav. 2001;74:177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Han PL. Optimization of chronic stress paradigms using anxiety- and depression-like behavioural parameters. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:497–507. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer JW. Arm function after stroke: from physiology to recovery. Sem Neurol. 2005;25:384–395. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-923533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugers HJ, Maslam S, Korf J, Joels M. The corticosterone synthesis inhibitor metyrapone prevents hypoxia/ischemia-induced loss of synaptic function in the rat hippocampus. Stroke. 2000;31:1162–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.5.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugers HJ, Kemper ARH, Korf J, Horst GJT, Knollema S. Metyrapone reduces rat brain damage and seizures after hypoxia–ischemia: an effect independent of modulation of plasma corticosterone levels? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:386–390. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199804000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SC, Dennis MS, O'Rourke SJ, Sharpe M. Negative attitudes among short-term stroke survivors predict worse long-term survival. Stroke. 2001;32:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.7.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLellan CL, Girgis J, Colbourne F. Delayed onset of prolonged hypothermia improves outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:432–440. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200404000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal JLM, Caso JR, de Cristobal J, Cardenas A, Leza JC, Lizasoain I, Lorenzo P, Moro MA. Effect of subacute and chronic immobilization stress on the outcome of permanent focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2003;979:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02892-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magarinos AM, McEwen BS. Stress-induced atrophy of apical dendrites of hippocampal ca3c neurons: comparison of stressors. Neuroscience. 1995;69:83–88. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00256-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May M, McCarron P, Stansfeld S, Ben-Shlomo Y, Gallacher J, Yarnell J, Smith GD, Elwood P, Ebrahim S. Does psychological distress predict the risk of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack? Stroke. 2002;33:7–12. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz GA, Whishaw IQ. Skilled reaching an action pattern: stability in rat (Rattus norvegicus) grasping movements as a function of changing food pellet size. J Neurosci Meth. 2000;116:111–122. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz GA, Schwab ME, Welzl H. The effects of acute and chronic stress on motor and sensory performance in male lewis rats. Physiol Behav. 2001;72:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz GA, Antonow-Schlorke I, Witte OW. Motor improvements after focal cortical ischemia in adult rats are mediated by compensatory mechanisms. Behav Brain Res. 2005a;162:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz GA, Jadavji NM, Smith K. Modulation of motor function by stress: a novel concept of the effects of stress and corticosterone on behavior. Eur J Neurosci. 2005b;22:1190–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklyaeva EI, Castaneda E, Whishaw IQ. Skilled reaching deficits in unilateral dopamine-depleted rats: impairments in movement and posture and compensatory adjustments. J Neurosci. 1994;14:7148–7158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-07148.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murros K, Fogelholm R, Kettunen S, Vuorela AL. Serum cortisol and outcome of ischemic brain infarction. J Neurol Sci. 1993;116:12–17. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90083-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nannetti L, Paci M, Pasquini J, Lombardi B, Taiti PG. Motor and functional recovery in patients with post-stroke depression. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:170–175. doi: 10.1080/09638280400009378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogun SA, Odusote KA. Effectiveness of high dose dexamethasone in the treatment of acute stroke. West Af J Med. 2001;20:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne RS, Tseng MT, Schurr A. The glucose paradox of cerebral ischemia: evidence for corticosterone involvement. Brain Res. 2003;971:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risedal A, Nordborg C, Johansson BB. Infarct volume and functional outcome after pre- and postoperative administration of metyrapone, a steroid synthesis inhibitor, in focal brain ischemia in the rat. Eur J Neurol. 1999;6:481–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.1999.640481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie LJ, De Butte M, Pappas BA. Chronic mild stress exacerbates the effects of permanent bilateral common carotid artery occlusion on CA1 neurons. Brain Res. 2004;1014:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandi C. Stress, cognitive impairments and cell adhesion molecules. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:917–930. doi: 10.1038/nrn1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. A mechanism for glucocorticoid toxicity in the hippocampus: increased neuronal vulnerability to metabolic insults. J Neurosci. 1985;5:1228–1232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-05-01228.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. Stress and plasticity in the limbic system. Neurochem Res. 2003;28:1735–1742. doi: 10.1023/a:1026021307833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, Pulsinelli WA. Glucocorticoids potentiate ischemic injury to neurons: therapeutic implications. Science. 1985;229:1397–1400. doi: 10.1126/science.4035356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocrine Rev. 2000;21:55–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheff S, Benardo LS, Cotman CW. Hydrocortisone administration retards axon sprouting in the adult rat dentate gyrus. Exp Neurol. 1980;68:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(80)90077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda K, Robinson RG. Effect of anxiety disorder on impairment and recovery from stroke. J Neuropsych Clin Neurosci. 1998;10:34–40. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slivka A, Murphy E, Horrocks L. Cerebral edema after temporary and permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Stroke. 1995;26:1061–1065. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Swintosky VL, Pettigrew LC, Sapolsky RM, Pharess C, Craddock SD, Brookes SM, Mattson MP. Metyrapone, an inhibitor of glucocorticoid production, reduces brain injury induced by focal and global ischemia and seizures. J Cer Blood Flow Metabol. 1997;16:585–598. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strekalova T, Spanagel R, Dolgov O, Bartsch D. Stress-induced hyperlocomotion as a confounding factor in anxiety and depression models in mice. Behav Pharmacol. 2005;16:171–180. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugo N, Hurn PD, Morahan B, Hattori K, Traystman RJ, DeVries AC. Social stress exacerbates focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Stroke. 2002;33:1660–1664. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000016967.76805.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas A, Chattarji S. Modulation of different states of anxiety-like behaviour by chronic stress. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:1450–1454. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.6.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ. Loss of the innate cortical engram for action patterns used in skilled reaching and the development of behavioral compensation following motor cortex lesions in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:788–805. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, O'Connor WT, Dunnett SB. Contributions of motor cortex, caudate–putamen and nigrostriatal systems to skilled forepaw use in the rat. Brain. 1986;109:805–843. doi: 10.1093/brain/109.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Pellis SM, Gorny B, Kolb B, Tetzlaff W. Proximal and distal impairments in rat forelimb use in follow unilateral pyramidal tract lesions. Behav Brain Res. 1993;56:59–76. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90022-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Gorny B, Sarna J. Paw and limb use in skilled and spontaneous reaching after pyramidal tract, red nucleus and combined lesions in the rat: behavioral and anatomical dissociations. Behav Brain Res. 1998;93:167–183. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaremba J. Hyperthermia in ischemic stroke. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:RA148–RA153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]