Abstract

The rat is an altricial species and consequently undergoes considerable postnatal development. Careful analysis of the emergence and disappearance of motor behaviours is essential to gain insight into the temporal pattern of maturation of motor system structures. This study presents a qualitative analysis of the developmental progression of skilled movement in the rat by using a skilled walking task. A new rung bridge task was used to expose rat pups to a novel environment in order to reveal their potential capabilities. Ten rat pups were filmed daily from postnatal day 7 through postnatal day 30 as they explored the rung bridge task. Discrete changes in skilled and non-skilled walking in fore- and hind-limbs were evaluated by scoring seven categories and 24 subcategories of motor behaviour, including limb flexion and extension, coordination, posture, sensorimotor responses, distal control, and tail use in rat pups. Frame-by-frame analysis of ambulatory movement revealed six distinct stages of locomotor development. The most significant transformation to mature gait patterns was found between postnatal days 15 and 19, and maturation of all motor behaviour was completed by postnatal day 27. The findings are discussed in relation to the maturation of underlying structures and their relevance to studies of brain damage.

Keywords: Skilled movement, Gait, Motor function, Ontogeny, Rung bridge stepping task

1. Introduction

The Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus) is an altricial species and consequently undergoes considerable postnatal development. Previous studies have discovered a number of particular motor behaviours that occur within certain time frames of rat pup development. For example, Altman and Sudarshan [1] observed pivoting and crawling behaviour, and Eilam [2] provided a time course of gait development. Furthermore, Westerga and Gramsbergen [19] noted significant time windows of musculoskeletal development that are paralleled by integration of descending and ascending systems [3–5]. These identifiably distinct stages of rat pup development are accompanied by corresponding behavioural modifications.

Most previous studies suggested that postnatal development of the rat central nervous system and associated behavioural changes follow two temporal gradients: a rostral–caudal and a ventral–dorsal gradient [6]. These gradients are mainly displayed as forelimb control preceding hind limb control [7]. However, there are exceptions to the rule of rostral–caudal/ventral–dorsal gradients in that forelimb elevation precedes head elevation [31]. Furthermore, appreciable differences exist between motor columns within a segment that deviate from the original notion of the existence of rostral–caudal/ventral–dorsal gradients in development [5]. It is possible that such exceptions to the absolute chronology of motor skill acquisition in rat ontogeny also exist for skilled movement.

Though extensive research has examined neural and anatomical motor system development, there is a dearth of research providing a time frame as to when these systems are functional at the behavioural level. The goal of the present study was to catenate previous observations into easily identifiable stages through qualitative analysis of skilled movement from postnatal day 7 to postnatal day 30 (P7–P30). Furthermore, the aim was to establish a time course as to when typical and atypical behaviours emerge and disappear. In order to assess the potential capabilities of rat pups it was important to place them in a novel environment to stimulate spontaneous behaviour and exploration. A novel apparatus, the rung bridge stepping task, was developed based on the ladder rung walking task (see [8,9]). The ladder rung walking task is commonly used to study skilled walking and recovery of function after brain injury in adult rats. The new rung bridge stepping task seemed an ideal apparatus for assessing ambulation and discrete fore- and hind-limb movements due to the complexity of skilled movement required to successfully traverse the apparatus. Based on early studies by Nornes and Das [6], we anticipated that qualitative behavioural analysis would reflect a temporal rostral–caudal gradient as well as a ventral–dorsal gradient during development of the central nervous system.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Two litters of Long-Evans Hooded rats (R. norvegicus), consisting of 16 and 19 pups, respectively, were used. Postnatal day 1 (P1) is considered the first calendar day of birth. Pups were housed in the Lethbridge vivarium with dam and littermates until weaned at 22 days. They were then split into two groups with littermates. Housing consisted of clear Plexiglas hanging cages (45.4 cm × 24 cm × 19.5 cm high) with 1/8″ Laboratory Animal Bedding (Bed-o’cobs, Andersons, Maumee, OH, USA). Food and water were available ab libitum. The housing room was maintained at 20–21 °C with a 12 h light-and-dark-cycle (lights on at 07:00). Animals were behaviourally tested in the morning hours from P7 to P30.

2.2. Behavioural testing

Five randomly chosen pups of either sex from each of the two litters (n = 10) were filmed for one trial daily at the same time of day from P7 to P30 on the rung bridge stepping task. Dams were kept in the testing room during testing until pups were weaned at 21 days.

2.3. Rung bridge stepping task apparatus

The rung bridge stepping task consisted of two Plexiglas walls connected by a floor of metal rungs, modified from the original ladder rung walking task as described by Metz and Whishaw [8], Metz and Whishaw [10]. Dimensions of the apparatus were 1 m in length, 20 cm in height, and 8 cm wide (see Fig. 1). The rungs were 3 mm in diameter and were arranged in sections at distances ranging from 1 to 3 cm. The placement of fore- and hind-limbs on the rungs was recorded. The rung bridge stepping task apparatus was placed on a table surface so that pups could place their limbs on the surface if they missed a rung. The rungs were elevated 1 cm above the table surface.

Fig. 1.

Photographs of rat pups performing the rung bridge stepping task. (A) A P7 animal illustrating forelimb use while hind limbs remain mainly passive. (B) A P10 animal showing fore- and hind-limb use and onset of occasionally weight bearing steps. (C) A P17 animal showing weight bearing and coordinated stepping patterns.

Each pup was filmed for 3 min or until it crossed the entire length of the apparatus. During later stages of development, rat pups traversed a distance of 50 cm (half the length of the apparatus) per trial while video recorded.

2.4. Video recording

Pups were filmed using either a Canon NTSC ZR50 or ZR50 MC Digital Video Camcorder (Canon USA Inc., Lake Success, NY). Video recordings were made on mini Digital Video Cassettes with a shutter speed of 1/500. The video recordings were analyzed frame-by-frame at 30 f/s.

2.5. Skilled walking rating score

Qualitative analysis of fore- and hind-limb ambulatory movements was performed using a novel rating scale (Table 1) comprising seven categories and 24 subcategories associated with skilled movement. The scoring system was developed based on movements made by adult rats. Each component was rated on a 3-point scale with a score of 0 for absent movement, a score of 1 for atypical movement, and a score of 2 for typical (adult-like) movement. Scores were normalized for the number of steps and mean scores were taken for each sequence. The evaluation of each of the movements listed in Table 1 is described in the following sections. Movements were analyzed across six major developmental stages: asynchronous activity (P1–P6); pivoting stage (P7–P10); crawling stage (P11–P14); integration stage (P15–P18); immature ambulation (P19–P26); mature ambulation (P27–30). Furthermore, spontaneous rearing and grooming behaviour was documented as well as the day of eye opening and ear unfolding.

Table 1.

Rung bridge stepping task qualitative rating scale for rats.

| Category | Behaviour scored | Rating scale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Orientation | Head orientation | 0 = opposite direction of movement |

| 1 = atypical or partial | ||

| 2 = complete adult pattern | ||

| Trunk orientation | 0 = opposite direction of movement | |

| 1 = atypical or partial | ||

| 2 = complete adult pattern | ||

| Limb orientation | 0 = 90–45° orientation | |

| 1 = 45–30° orientation | ||

| 2 = <30° | ||

| 2. Flexor/extensor activity | Flexion of paw | 0 = absent |

| 1 = partial | ||

| 2 = present | ||

| Extension of paw | 0 = absent | |

| 1 = partial | ||

| 2 = present | ||

| Close digits with lift | 0 = no close | |

| 1 = partial close | ||

| 2 = complete close | ||

| 3. Gait development | Placement on rung | 0 = absent |

| 1 = attempt without placement | ||

| 2 = foot placed on rung | ||

| Abduction of limb | 0 = present | |

| 1 = partial | ||

| 2 = absent | ||

| Adduction of limb | 0 = present | |

| 1 = partial | ||

| 2 = absent | ||

| Coordinated stepping pattern | 0 = no coordinated movements | |

| 1 = stop-and-go movements | ||

| 2 = stepping pattern | ||

| 4. Postural control | Weight bearing | 0 = no weight bearing steps |

| 1 = occasional weight bearing steps | ||

| 2 = frequent weight bearing steps | ||

| Base of support | 0 = lateral HL position | |

| 1 = broad base | ||

| 2 = narrow base | ||

| Limb placement on rung | 0 = 90–45° | |

| 1 = 45–30° | ||

| 2 = <30° | ||

| 5. Sensorimotor | Placing response when lifting | 0 = full miss |

| 1 = contact placing | ||

| 2 = no rung contact before placement | ||

| Footfall recovery | 0 = deep slips/falls, no replacement | |

| 1 = loss of balance followed by replacement | ||

| 2 = able to catch deep falls | ||

| Foot slip recovery | 0 = no replacement | |

| 1 = placement with foot slip | ||

| 2 = recovered foot slip | ||

| Step in-between rungs | 0 = no active lift | |

| 1 = partial lift/delayed lift | ||

| 2 = active lift and placement | ||

| Adjustment on rung | 0 = no adjustment | |

| 1 = partial adjustment | ||

| 2 = complete repositioning | ||

| Aim for rung | 0 = no placement | |

| 1 = random placement | ||

| 2 = lift and placement | ||

| 6. Distal control | Digits used | 0 = only 1 or 2 digits |

| 1 = 3 digits or split grasp | ||

| 2 = full palm | ||

| Grip flexion | 0 = none/flat palm | |

| 1 = partial flexion | ||

| 2 = full grip with flexion of paw | ||

| Arpeggio | 0 = absent | |

| 1 = partial | ||

| 2 = full | ||

| 7. Tail | Tail use | 0 = down, passive use/non-use |

| 1 = erect parallel to ground when walking | ||

| 2 = erect above torso |

2.5.1. Orientation

Orientation of head, trunk and limb were scored using three main categories.

Head orientation

Animals received a score of 0 in this category when their upper torso and/or head were opposite to the direction of movement. Animals received a score of 1 when the head was lateral to the direction of the movement. If the head was facing forward or towards the direction of the movement, a score of 2 was given.

Trunk orientation

Animals received a score of 0 when the caudal region of the trunk was in an orientation opposite to the direction of movement. A score of 1 was given when the trunk was lateral to the direction of movement. A score of 2 was given if the trunk aligned with the direction of movement.

Limb orientation

Animals received a score of 0 when the limb was at a 90–45° angle relative to the trunk. A score of 1 was given when the limb was positioned at a 45–30° angle, and a score of 2 was given when the limb was positioned at an angle greater than 30°.

2.5.2. Flexor/extensor activity of paw and digits

Paw and digit flexion and extension were measured by three categories, modified from Metz and Whishaw [8].

Flexion

Animals received a score of 0 when no flexion of the wrist was observed. A score of 1 was given when the wrist exhibited partial flexion, and a score of 2 was given when the wrist exhibited full flexion.

Extension

An animal received a score of 0 when it did not extend its paw and digits after a lift (see Fig. 3A). A score of 1 was given when the animal opened its digits without an extension parallel to the rungs. A score of 2 was given when the paw and digits were extended parallel to the rung before placement.

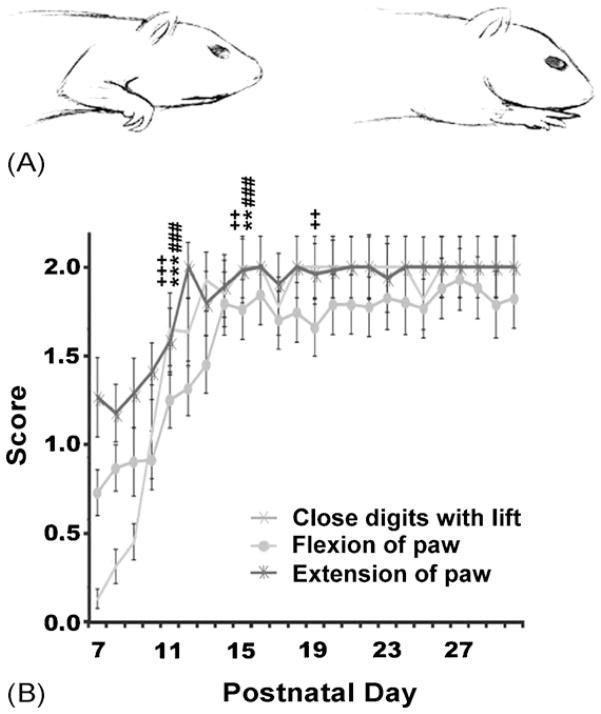

Fig. 3.

Digit flexion and extension. (A) Schematic illustration of flexion and extension of digits. (B) Time course illustrating scores for paw flexion, paw extension and digit flexion. Note that pups frequently exhibited paw flexion and the ability to close digits at P12. By P13 pups were able to consistently extend their paw and digits parallel to the surface of rungs before placement. Symbols indicate significances compared to previous developmental stage (P7–10, P11–P14, or P15–18, respectively): **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for flexion of paw; ###p < 0.001 for extension of paw; ++p < 0.01, +++p < 0.001 for close digits with lift.

Close digits with lift

An animal received a score of 0 when the paw remained open and digits extended with a lift from the surface or rung. A score of 1 was given when the digits came together with a partial flexion. A score of 2 was given when the digits were closed upon lifting with full flexion.

2.5.3. Gait development

Limb placement, abduction and adduction were scored separately for fore- or hind-limbs.

Placement on rung

Animals received a score of 0 when no apparent attempt to place the limb on a rung was made. A score of 1 was given when the pup initiated an attempt to place the limb on a rung but was unable to reach the rung or place the limb. A score of 2 was given when the animal made a successful attempt to place the limb on a rung, regardless of the quality of the placement.

Abduction

An animal received a score of 0 when lateral articulation of the limb was observed. If the animal exhibited partial limb abduction it was given a score of 1 and if it demonstrated forward stepping without lateral diversion it was given a score of 2. The hind limb was also scored for abduction using the same criteria for 0 and 1 though a slight abduction of the hind limb was permitted for a score of 2 as this reflects the adult movement.

Adduction

An animal received a score of 0 when the limb showed articulation towards the body axis. A score of 1 was given when the limb exhibited partial limb adduction, and a score of 2 was given when forward stepping occurred without any adduction.

Coordinated stepping pattern

Stepping coordination was scored according to the description of lateral walk by Eilam [2]. An animal received a score of 0 when the forelimb and hind limb did not alternate in succession. A score of 1 was given when there was more than a 50% overlap of the swing phase of two successive steps and a score of 2 was given when the hind limb and forelimb step were in succession with no more than a 50% overlap of the swing phase of two successive steps.

2.5.4. Postural control

Postural control was measured as indicated by weight bearing, base of support and limb placement.

Weight bearing

An animal received a score of 0 when it did not elevate the trunk from the surface/rungs. A score of 1 was given when the trunk was elevated with partial support. A score of 2 was given when the animal lifted its shoulders and hindquarter off the surface.

Base of support

A score of 0 was given when the hind limbs were oriented at an angle of greater than 30° away from the body. A score of 1 was given when the hind limbs were oriented laterally from the body, but less than 30° away. A score of 2 was given when the hind limbs were tucked underneath the torso.

Limb placement on rung

A score of 0 was given when the limb was placed on the rung with an ulnar deviation between 45° and 90°. An ulnar deviation of 30–45° was scored as 1 point and a deviation of <30° was given a score of 2 points.

2.5.5. Sensorimotor responses

Five separate behaviours were scored to assess sensorimotor responses. Scores were based on an earlier error rating scale [8,9]. Fore- and hind-limbs were scored separately.

Placing response on rung

A score of 0 was given when the pup attempted to place a limb on a rung but slipped off and did not bear weight. A score of 1 was given when a limb was placed on a rung but the animal used other rungs for orientation or if the paw touched the rung prior to placement (contact placing). A score of 2 was given when the limb was placed on a single rung without prior contact to another rung.

Footfall recovery

This category scores deep foot falls in-between rungs that are accompanied by loss of balance and interruption of the gait pattern. A score of 0 was given when the limb fell in-between rungs and was not withdrawn immediately. As a consequence, the animal’s balance was disturbed and the limb remained off the rung for a considerable period of time. A score of 1 was given when a deep fall occurred resulting in disturbed balance, however, with a small delay the limb was still placed on a rung. A score of 2 was given when a deep fall occurred and the limb was immediately withdrawn and placed on a rung again.

Foot slip recovery

This category scores foot slips in which the limb contacted a rung but then slipped off. A score of 0 was given when the limb slipped off a rung and was not withdrawn immediately. As a consequence, the animal’s balance was disturbed and the limb remained off the rung for a considerable period of time. A score of 1 was given when the limb was withdrawn and placed on a rung with a small delay. A score of 2 was given when a slip occurred and the limb was immediately withdrawn and placed on a rung again.

Step in-between rungs

When missing a rung, an adult rat will step back onto the rung immediately. A score of 0 was given when a limb missed the rung and was not lifted back onto the rung immediately. A score of 1 was given when the limb was lifted back onto the rung either partially or after a delay. A score of 2 was given when the limb immediately stepped back onto the rung.

Adjustment on rung

Adult animals often reposition a limb on a rung so that the midportion of the palm of the limb is placed on the rung for optimal weight support. A score of 0 was given when the limb was not repositioned after a partial placement occurred. A score of 1 was given when the limb was slightly adjusted but not fully repositioned on the rung, however, when weight bearing the midportion of the palm was not weight bearing. A score of 2 was given when the limb was fully repositioned by a movement of either the limb or trunk of the body. The midportion of the palm of the limb was placed on the rung (score 6 in adult scale, see [8]).

Aim for rung

A score of 0 was given when an attempt was made to place on a rung but the paw did not make contact with a rung. A score of 1 was given when a paw was randomly placed on a rung or touched more than one rung. A score of 2 was given if the paw was placed on the rung aimed for.

2.5.6. Distal limb control

Distal limb control was scored by indices of digit use, grasping a rung, or arpeggio movement. Fore- and hind-limbs were scored separately.

Digits used

A score of 0 was given when only one or two digits were used to grasp a rung. A score of 1 was given when three or four digits were used to contact the rung. A score of 2 was given when all digits were used and the limb was placed on the midportion of the palm.

Grip flexion

A score of 0 was given when the palm remained flat (no digit flexion) or slipped off the rungs. A score of 1 was given when the digits were partially flexed to grasp the rung, and a score of 2 was given when the paw exhibited full flexion with digits wrapped firmly around the rung.

Arpeggio

A score of 0 was given if the paw was placed flat on the rung. A score of 1 was given if the wrist partially pronated and some of the digits 5 through 2 were used to grip the rung. A score of 2 was given if the wrist pronated and digits 5 through 2 were used to grip the rung.

2.5.7. Tail use

A score of 0 was given when the tail was held low and it remained passive. A score of 1 was given when the tail was erect parallel to the rungs during a stepping cycle. A score of 2 was given when the tail was erect during locomotion.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using a SPSS software package 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, 2002). The results were subject to repeated measurements analysis of variance (ANOVA) across testing sessions. Pair-wise comparisons were made using post hoc LSD tests. A p-value of less than 0.05 was chosen as significance level. All data are presented as mean ± standard error.

3. Results

3.1. Orientation

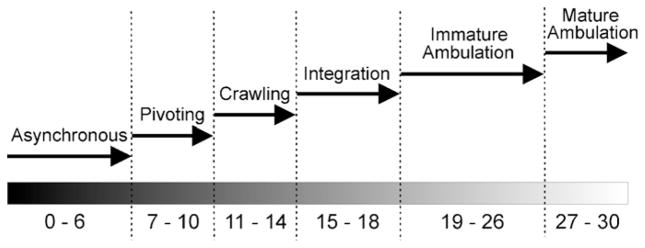

3.1.1. Head, trunk and limb orientation

At the time of scoring (P7) the pups were already able to orient their head in the direction of movement (Fig. 2). However, much of the time the head was lateral to the torso while the pup tried to align the torso. By P12 the pup was able to align its head and torso in the direction of movement. Anchoring of the hind limbs inhibited the alignment of the trunk with the head.

Fig. 2.

Time course showing head, trunk and limb orientation. At P7 the pups were able to orient their head in the direction of movement. By P12 pups were able to align their head and torso in the direction of movement.

3.2. Flexor/extensor activity

3.2.1. Flexion of paw

Pups at P7 did not exhibit flexion of paw with each lift. Conversely, digits remained spread and extended with each lift. Pups first began to exhibit flexion of the paw between P7 and P10 (Fig. 3B). By P12 the pups frequently exhibited paw flexion with each lift. There was a significant difference across time for flexion of paw (F(5,135) = 26.89, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between stages P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), and between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.05) with no significant changes after this time point.

3.2.2. Extension of paw

Pups at P7–P10 did not consistently extend their paw parallel to the surface after each flexion (Fig. 3B). By P13 pups most frequently extended their paw and digits parallel to the surface of rungs before placement. There was a significant difference across time for extension of paw (F(5,135) = 78.45, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), and between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001) with no significant changes between stages after this point in time.

3.2.3. Close digits with lift

Pups did not close their digits with a lift until after flexion of the paw was present at P12 (see Fig. 3B). Before P12 the pups’ paws remained open with digits splayed and extended with each lift from the surface or rung. After P12, along with flex-ion, the digits would regularly close with lift from the surface or rung. There was a significant difference across time for the category of close digits with lift (F(5,135) = 174.44, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.01), and between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.01) with no significant changes between stages after this time point.

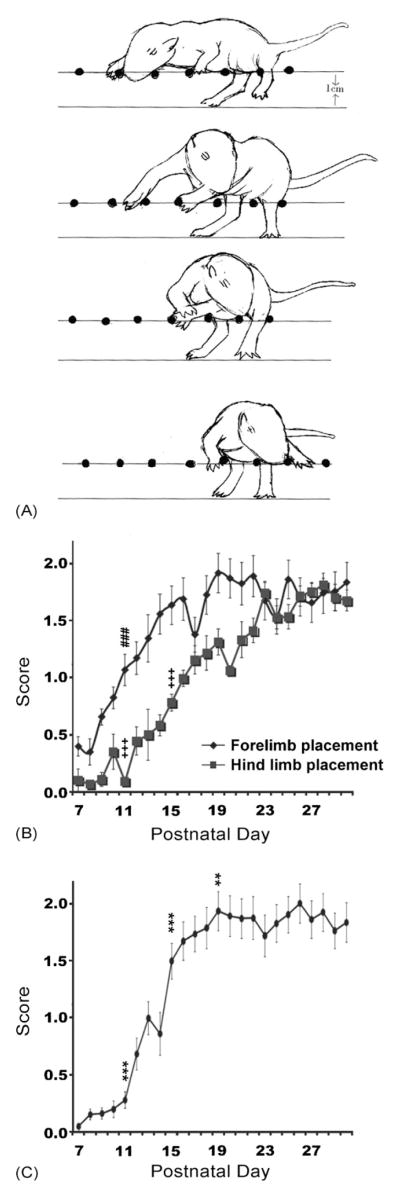

3.3. Gait development

3.3.1. Attempt to place on rung (forelimb)

Although the placing response did not reach adult values until P17, the pups made attempts to place their forelimbs on a rung as early as P7 (Fig. 4B). There was a significant difference across stages for attempts to place on rung (F(5,135) = 8.15, p < 0.001) with significant changes between P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Gait development. (A) Schematic illustration of a pivoting movement on the apparatus by P7. (B) The ability to attempt forelimb and hind limb placements on a rung, and (C) the ability to perform coordinated fore- and hind-limb stepping movements. Note the delayed onset of hind limb placement on rungs as compared to forelimb placement (P14 for forelimb vs. P23 for hind limb). Pups consistently traversed the rungs in a coordinated stepping pattern after P22. Symbols indicate significances compared to previous developmental stage (P7–10, P11–P14, or P15–18, respectively): ###p < 0.001 for forelimb placement; +++p < 0.001 for hind limb placement; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for coordination.

3.3.2. Attempt to place on rung (hind limb)

From P7 to P10, the hind limbs served mainly as an anchor for the body to pivot around (Fig. 4A). There was a pronounced latency between forelimb and hind limb attempts to place on rungs (P14 for forelimb vs. P23 for hind limb; see Fig. 4B). There was a significant difference across stages for hind limb attempts to place on rung (F(5,135) = 179.33, p < 0.001). There was a significant difference for hind limb attempt to place on rung between stages P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), and between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001) and no significant change after that point. There was, however, a trend towards significance between stages P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p = 0.058).

3.3.3. Abduction of forelimb

Pups at P7–P10 would engage forelimbs in a 0° lateral to torso to greater than 90° articulation, often crossing to the contralateral side. There was a significant difference across stages in forelimb abduction (F(5,135) = 245.13, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between stages P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001), and between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.05), with no significant changes occurring after P22 when the pup demonstrated forward stepping without lateral diversion.

3.3.4. Abduction of hind limb

There was a significant delay in the ability to perform fore-limb to hind limb abduction. There was a significant difference across stages for hind limb abduction (F(5,135) = 116.51, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.01), between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.001) with no significant change occurring after P20.

3.3.5. Adduction

Pups at P7–P14 exhibited extreme adduction across the midline to the contralateral side. Between P14 and P17 the fore- or hind-limb would be brought slightly beyond alignment with the shoulder to midline placement. After P17 the pups demonstrated forward stepping without contralateral deviation. There was a significant difference across stages for limb adduction (F(5,135) = 237.26, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between stages P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), and between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001) with no significant changes occurring after this stage.

3.3.6. Coordinated stepping pattern

Pups did not exhibit a complete stepping cycle until after P13 (see Fig. 4C). From P14 through P22 pups showed bursts of coordinated stepping followed by stops and turning on the rungs. After P22 pups consistently traversed the rungs in a coordinated stepping pattern without stop-and-go behaviour. There was a significant difference across stages for the coordinated stepping pattern (F(5,135) = 238.83, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001), and between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.01) with no significant changes occurring after P22.

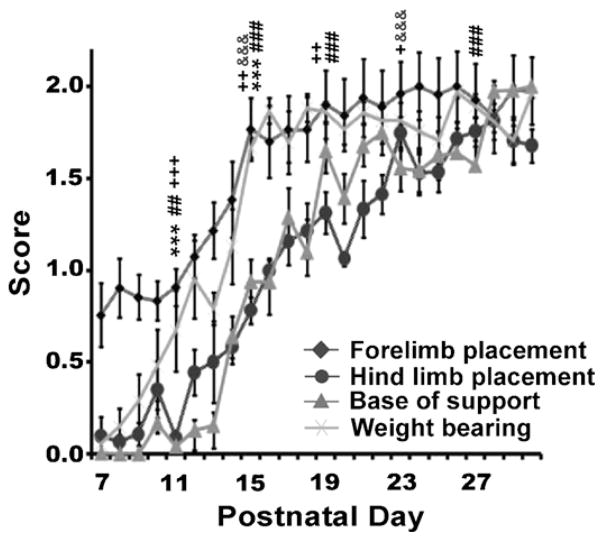

3.4. Postural control

3.4.1. Weight bearing

Between P7 and P10 pups were unable to elevate their shoulders or pelvis from the surface for more than a few seconds. From P11 to P14 pups were able to elevate shoulders and pelvis only long enough to partially complete a stepping cycle. There was a significant increase in weight bearing between P14 and P15 (p < 0.05) when pups were able to remain elevated from the surface (Fig. 5). There was a significant difference across stages for weight bearing (F(5,135) = 106.10, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed changes from stage P7–P10 to P11–P14 (p < 0.001), and between P11–P14 and P15–P19 (p < 0.001), with no significant changes between groups after this time point.

Fig. 5.

Time course showing development of postural control. Rat pups show patterns of adult postural support by P15 in weight bearing, by P22 in forelimb and hind limb position, and by P27 in base of support. Symbols indicate significances compared to previous developmental stage (P7–10, P11–P14, P15–18, or P19–26, respectively): ***p < 0.001 for weight bearing; ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 for base of support; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, +++p < 0.001 for forelimb placement; &&&p < 0.001 for hind limb placement.

3.4.2. Base of support

Between P7 and P13 the pups’ hind limbs extended laterally from the hip (see Fig. 5). There was a significant change from P13 to P15, (p < 0.001). Between P15 and P26 the pups maintained a broad base of support. After P27, the pups’ hind limbs were tucked directly under the hips. There was a significant difference across stages for base of support (F(5,135) = 170.72, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes from stage P7–P10 to P11–P14 (p < 0.01), from P11–P14 to P15–P18 (p < 0.001), and from stage P15–P18 to P19–P22 (p < 0.001). There was no significant change between P19–P22 and P23–P26 but a significant change between P23–P26 and P27–P30 (p < 0.001). Base of support was the last of the subcategories to reach adult values.

3.4.3. Forelimb placement on rung

Between P7 and P11 pups exhibited ulnar deviation between 45° and 90° (Fig. 5). Between P11 and P14 the pups exhibited less exorotation of the limb with values between 45° and 30°. By P22 the pups were placing their forelimbs at an angle of ≤30°. There was a significant difference across stages for placement on rung (F(5,135) = 97.18, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between stage P7–P10 and P11–P14, (p < 0.001), between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.01), between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.01), and between P19–P22 and P23–26 (p < 0.05) with no significant change after this time point.

3.4.4. Hind limb placement on rung

Between P7 and P14 pups made very few attempts to lift the hind limb onto the rung (Fig. 5). The hind limbs remained predominantly anchored. From P15 to P18 the pups began to use their hind limbs, which also facilitated forward locomotion. However, hind limbs were placed between 45° and 90° (see Fig. 3). Between P19 and P22 pups places their hind limbs at an angle of approximately 30–45°. There was no significant difference between P7–P10 and P11–P14 (note: there was very little attempt to lift the hind limb on rung and no apparent aim for the rung at these two stages; the hind limb remained predominantly anchored). There was a significant difference across stages for the placing response when lifting (F(5,135) = 90.07, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between stages P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001), and between P19–P22 and P23–26 (p < 0.001) but no significant change occurred after this time point.

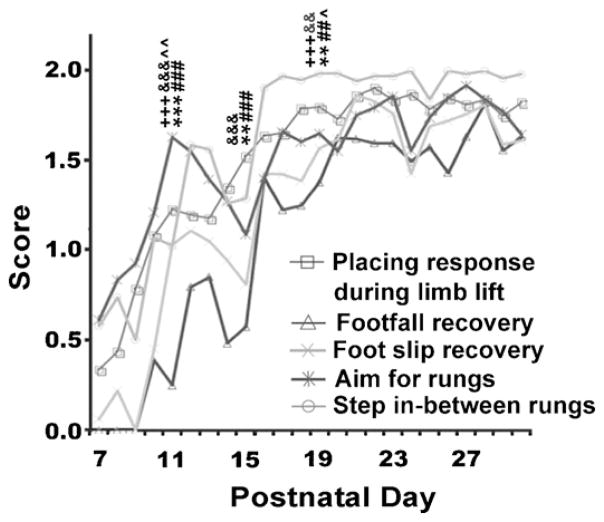

3.5. Sensorimotor responses

3.5.1. Placing response on rung

Between P7 and P10 pups frequently attempted to place their forelimbs on a rung but missed (Fig. 6). Between P11–P15 and P15–P18 pups placed their forelimbs on a rung using another rung for orientation or contact placing. After P20 pups were able to place their limbs on a single rung without prior contact with a rung. There was a significant difference across stages for placing response when lifting (F(5,135) = 55.89, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes from stages P7–P10 to P11–P14 (p < 0.001), from P11–P14 to P15–P18 (p < 0.01), and from P15–P18 to P19–P22 (p < 0.01) with no significant change after this time point.

Fig. 6.

Time course illustrating development of sensorimotor responses. Pups assumed adult patterns of limb placement responses and return after steps in-between rungs by P20. Limbs showed immediate recovery from foot falls and foot slips at P19. By P15 the pups were able to lift the paw and successfully place on a single rung. Symbols indicate significances compared to previous developmental stage (P7–10, P11–P14, or P15–P18, respectively): **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for placing response; ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 for footfall recovery; +++p < 0.001 for foot slip recovery; &&p < 0.01, &&&p < 0.001 for step in-between rungs; ^p < 0.05, ^^p < 0.01 for aim for rungs.

3.5.2. Footfall recovery

Between P7 and P10 pups were unable to recover from a deep fall and the paw/foot remained off the rung (Fig. 6). Between P11 and P18 pups attempted to recover from a foot fall and, though they replaced their paws on a rung, the pup did not immediately resume rhythmic stepping activity. By P19 pups were able to immediately recover from a footfall. There was a significant difference across stages for footfall recovery (F(5,135) = 99.41, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between stages P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), between P12–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001), and between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.01) with no significant change after this time point.

3.5.3. Foot slip recovery

Between P7 and P10 pups were not able to recover from a foot slip. Between P11 and P14 pups attempted to recover from a foot slip though would not recover full stability on the rung. After P15 pups were able to recover from foot slips reaching adult values at P19 (see Fig. 6). There was a significant difference across stages for foot slip recovery (F(5,135) = 76.71, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between stages P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001) and between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.001) with no significant change between stages after this time point.

3.5.4. Step in-between rungs

Between P7 and P10 pups did not attempt to place their foot back on the rung after it slipped in-between the rungs (Fig. 6). There was a significant difference across stages for stepping in-between rungs (F(5,135) = 237.84, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001), and between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.01), with no significant change after this time point.

3.5.5. Adjustment on rung

Between P7 and P10 pups partially placed their limbs on the rung and did not attempt to make adjustments on the rung which would help it gain better stability. Between P11 and P14 pups made a slight, often unsuccessful, adjustment on a rung. There was a significant change in the pups’ ability to successfully adjust limb position on the rungs from partial to full placement between P15 and P16 (p < 0.001). There was a significant difference across stages for adjustment on rung (F(5,135) = 82.61, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant differences between stage P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001), and between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.01) with no significant change after this time point.

3.5.6. Aim for rung

Between P7 and P10 the pups did not place their paw on the rung (Fig. 6). Between P11 and P14 the pups exhibited random placement on the rungs. By P15 the pups were able to lift the paw and successfully place on a single rung. There was a significant difference across stages for aim for rungs (F(5,135) = 29.35, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.01), and between P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.05) with no significant changes occurring after this period of time.

3.6. Distal control

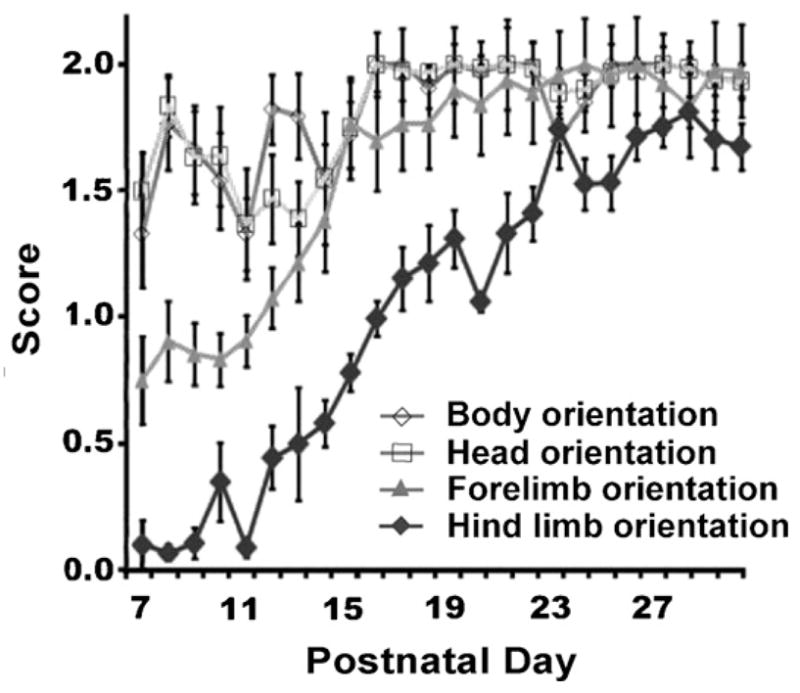

3.6.1. Digits used

Between P7 and P10 the pups’ digits remained open and extended. Though the pups could exhibit partial flexion if the mid-line of the palm was placed across a rung, the pups were not able to grasp the rung using their digits. Between P11 and P14, pups began to use their digits to grasp a rung (Fig. 7). However, pups typically used only 3 or 4 digits split by the rung. By P15 the pups were able to place their full paw on the rung with digits wrapping around the rung (see Fig. 7). There was a significant difference across stages for digits used (F(5,135) = 61.10, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant differences between stages P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001) and between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.01), with no significant change across stages after this time point.

Fig. 7.

Time course showing the emergence of distal limb control. Between P11 and P14, pups began to use their digits to grasp a rung. By P15 the pups were able to place their full paw on the rung with digits wrapping around the rung. By P16 the pups exhibited full grip flexion with digits firmly wrapped around a rung. Digit use by arpeggio movement showed adult patterns by P17. Symbols indicate significances compared to previous developmental stage (P7–10, P11–P14, P15–P18, or P19–P26, respectively): **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for digits used; ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 for grip flexion; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, +++p < 0.001 for arpeggio.

3.6.2. Grip flexion

Between P7 and P10 the pups placed their limbs on a rung with a flat palm and frequently slipped off the rung. Between P11 and P14 the pups exhibited partial flexion around the rung but did not firmly grasp it. By P16 the pups exhibited full grip flexion with digits firmly wrapped around a rung (Fig. 7). There was a significant difference across stages for grip flexion (F(5,135) = 63.00, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant differences between stages P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001) and between P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.01) with no significant change after this time point.

3.6.3. Arpeggio

The time course of the arpeggio movement is shown in Fig. 7. Animals began to consistently use an arpeggio movement of digits 5 through 2 at P17. There was a significant difference across stages for arpeggio (F(5,135) = 113.476, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant difference between stage P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), P11–P14 and P15–P18 (p < 0.001), P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.01), with no significant change between stages P19–P22 and P23–P26. There was however, a significant change between P19–22 and P27–P30 (p < 0.05).

3.7. Tail

3.7.1. Tail use

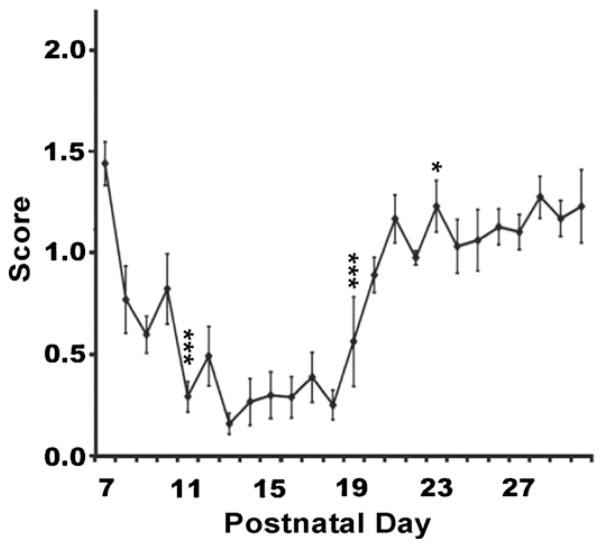

Between P7 and P10 the pups’ tail was erect during ambulatory movements. Between P11 and P18 the tail was predominately held low and passive. However, pups “flicked” their tail erect during a slip or fall. Between P19 and P30 the tail was predominantly erect parallel to the rungs as pups traversed the apparatus unless they experienced a slip or fall at which time, as in the previous stages, the tail would “flick” (Fig. 8). There was a significant difference across stages for tail use (F(5,135) = 33.58, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed significant changes between stages P7–P10 and P11–P14 (p < 0.001), but no significant change between stages P11–P14 and P15–P18 (Fig. 8). There was a significant change between stages P15–P18 and P19–P22 (p < 0.001), and between P19–P22 and P23–P26 (p < 0.05) and no significant changes between P22–P26 and P27–P30.

Fig. 8.

Time course of tail use during ambulation. The tail was erect between P7 and P10. Between P11 and P18 the tail was predominately held low and passive. Between P19 and P30 the tail was predominantly erect parallel to the rungs as pups traversed the apparatus. Asterisks indicate significances compared to previous developmental stage (P7–10, P15–18, or P19–22, respectively): *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

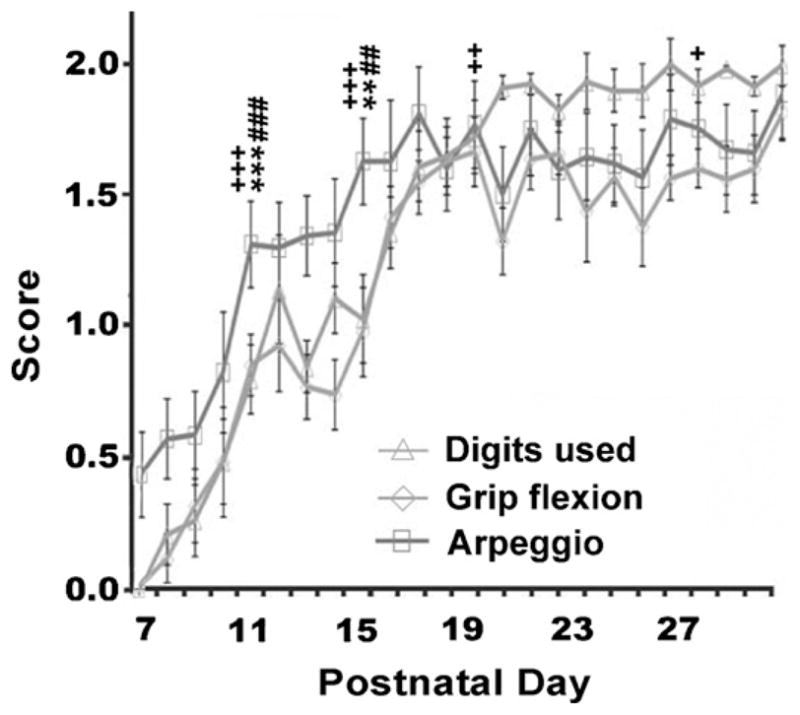

The present study describes the acquisition of fine and gross motor skill in rat ontogeny from P7 to P30 using a new rung bridge stepping task to assess limb placement. Discrete movements were scored as they appeared and disappeared during early development. The progression from atypical movement to mature ambulation was achieved relatively quickly (less than 30 days) yet slow enough to reveal a steady progression of skill acquisition. Based on detailed analysis of discrete movements and building upon previous observations and studies, the ontogeny of rat pup movement can be organized into six distinct stages: asynchronous activity, pivoting stage, crawling stage, integration stage, immature ambulation, and mature ambulation (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Time course illustrating the six distinct stages of skilled walking development.

4.1. Asynchronous activity stage (P1–P6)

Between P1 and P6, pups would not attempt to traverse the rung bridge stepping task. Therefore, pup movement was observed in the home cage. At this stage, fore- and-hind limb movements were asynchronous and limbs projected lateral to torso. Research conducted by Fady and co-workers [29] found that pups at this stage are able to respond to olfactory stimulation and orient towards the stimulus. However, pups were unable to ambulate in the direction of the stimulus indicating that incentive is not the limiting factor in locomotion at this stage. Jamon and Clarac [30] posit that the main limiting factor in locomotion is the immaturity of vestibular and somesthetic antigravity systems preventing pups from elevating their shoulders or hips from the surface. Further, before P6 the corticospinal tract, which controls voluntary, distal limb movements, has not reached the lumbar spinal segments [14], which likely accounts for asynchronous behaviour of the caudal regions. At this stage the paws exhibit ulnar deviation and digits remain open and extended. Asynchronous behaviour was also found in swimming tasks [11].

4.2. Pivoting stage (P7–P10)

Between P7 and P10, ambulatory movement is mainly characterized by pivoting [1]. During this stage pups mainly used forelimbs in an abduct/adduct pattern while hind limbs remained predominately passive (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, pups were able to elevate their shoulders very briefly to facilitate turning of the head lateral to their body. Lateral head orientation was followed by forelimb abduction in the direction of head movement and an adduction of the contralateral forelimb. Digits were splayed with paw lift and exhibited synchronicity. The undifferentiated use of digits is not surprising due to polyneuronal innervation of muscle fibers until P10 [12]. Though adult muscle fibers are individually innervated, at this stage of development, each muscle fiber receives synaptic input from two or more motor neurons [4,12]. Interestingly, if pups made contact with a rung, the paw would exhibit a partial grip flexion. Considering that at this stage contact with the rung was necessary to induce grip flexion, grip flexion was likely a grasp reflex and not skilled movement. Jamon [4] has suggested that the inability to ambulate at this time is not entirely due to the immaturity of underlying systems but has adaptive advantages namely, preventing pups from leaving the home nest. Indeed, pups did occasionally take a few steps across the rungs before resuming pivoting behaviour, indicating that the potential for an immature form of locomotion exists (Fig. 1B) but is being inhibited at another level.

4.2.1. Crawling stage (P11–P14)

Between P11 and P14 pups began to exhibit crawling behaviour. Although basic motor skills were present at this stage, locomotion was atypical of the adult gait. At this stage gait reflected an immature form of lateral walking. Weight bearing was possible only for a few steps, resulting in stop-and-go behaviour. Previous studies found that the tonic electromyographic firing rate of the soleus muscle is approximately 9% of its adult values, which may relate to both polysynaptic innervation [13] and immature development of muscle spindles [19]. Although by P11 the descending spinal systems necessary for adult locomotion reach lumbar levels [14], the inability to perform consistent weight bearing is likely the main limiting influence on locomotion at this stage.

By P12 pups were demonstrating fairly consistent paw flexion with lift and extension of the paw parallel to the rung prior to placement. Flexion and extension of the paw were the first recognizable locomotor movements to reach adult values in pre-walking developmental stages. This pattern appeared soon after digits became innervated by lateral corticospinal tract projections [15].

Despite the fact that eyes were still closed, pups could orient in the forward direction and attempt to cross the apparatus. Pups were most likely using vibrissae tactile cues to orient and place. Although pups would attempt to cross the apparatus, sensorimotor and distal movements were not fully developed. Various neuroanatomical studies indicate that both the rubrospinal pathway, which controls voluntary movements through regulating flexor and extensor muscles, and the corticospinal system, controlling fine distal movements, are not fully developed at this stage [16], producing a proximal–distal gradient. A rostral–caudal gradient was also observed when comparing forelimb movement to hind limb movement. Therefore, although the pups were beginning to ambulate, the immaturity of the underlying systems prevented coordinated gait patterns at this stage in development.

4.3. Integration stage (P15–P18)

The most significant transformation to a mature gait pattern occurred between P15 and P18. Although the basic elements of quadrupedal locomotion are present soon after birth and rhythmic forelimb-hind limb stepping patterns could be induced by subcutaneous injection of L-dopa as early as P3 [17], it appears that the activation of central pattern generators that govern the rhythmic activity of locomotion are dependent on the maturation of descending and ascending neural pathways, commissural interneurons [5] as well as musculoskeletal maturity [20]. The present study shows that also sensorimotor maturation begins to reach adult values at this time (see Fig. 6), indicating that propriospinal and sensorimotor connections become functionally meaningful (for detailed review see [3]).

In addition to inter-limb coordination, distal limb control also reached adult values between P15 and P18. This finding is in line with disappearance of polyneuronal innervation of digits by P16–P17 [12]. Furthermore, pups showed improved weight bearing and greater hind limb control on the apparatus (Fig. 1C), which is supported by the observation that motor neurons become organized into bundles to mediate fine-tuned electromyographic activity of the soleus muscle at approximately P16 [18,19]. According to Hultborn and Nielsen [20], two specific proprioceptive inputs, reflecting the position of the hip and the load on extensors, seem to have a critical effect on the timing of the different phases in the locomotor cycle suggesting posture is also an important pro-prioceptive measure. Early studies by Lundberg [21] posit that it is this complex pattern of proprioceptive reflexes which help to facilitate the coordination of muscle activity involved in locomotion. Although in the present study this stage was characterized by digitigrade locomotion and the emergence of new motor skills, movements still remained atypical of the adult gait. The pups were relatively slow in crossing the rung bridge and there was a lack of overall fluidity in their movement, which changed to a major degree in the subsequent stage.

4.4. Immature ambulation stage (P19–P26)

The immature ambulation stage extended from P19 to P26 and was characterized as a period of hypervelocity. Although pups were able to cross the rung bridge quickly, they made significantly more mistakes than adult rats. It is possible that the number of foot placement errors on rungs is negatively related to the speed of locomotion [22]. By P19 pups were using stepping patterns that are typical of adult animals [2] and were no longer abducting or adducting their forelimbs though the hind limb was still slightly abducting from the hip. Placement of the paw and orientation of forelimbs were adult-like at P19 with latency for hind limbs of 5 days.

At this stage, skilled movements also showed rapid development. Pups demonstrated skilled movement with adult-like aiming for rungs, placement on rungs, recovering from falls and compensating for slips made while stepping on rungs. Grip flexion was used when grasping a rung and pups demonstrated the ability to make adjustments on the rungs for better stability. Though pups exhibited adult-like movement scores in crossing the rung bridge by P23, their foot placement remained slightly exorotated until P25. The base of support, however, remained broader than that of adult animals throughout this stage.

4.5. Mature ambulation (P27–P30)

By P27 movements in all categories had reached asymptote. The last category to reach adult performance values was the distance between feet, as indicated by the base of support. The adoption of a broader base of support might reflect the attempt to maintain a coordinated gait pattern while balance and postural stability are compromised [23].

5. General considerations

In the light of previous data, some considerations for interpretation of the present observations need to be made. In particular, the results might have varied with the absence of a supporting platform underneath the rung surface. As reported by Schallert et al. [24], offering a supporting platform in a challenging locomotor task will encourage limb use and reduce the need for adopting compensatory strategies. While this strategy was suggested to unravel the true abilities of rodents with brain damage, the same might apply to the developing pup and reflect the interaction among the maturation of brain systems mediating locomotor functions and sensorimotor learning.

The present findings are supported by previous studies using alternate methodology of footprint, kinematic and qualitative gait analyses in rats [2,19]. Moreover, the findings in the rat are paralleled by observations in other species, also showing a linear relationship between functional morphology and onset of different gait patterns [2,25]. While the sequence of developmental stages is similar between species, there are variations in the time course of development. Variations might derive from different durations of growth and the degree of gait complexity, as more specialized gaits are terminally added to the basic patterns [2].

On a general note, the present study did not attempt to dissociate sex differences. It is possible that the ontogeny of skilled walking might show differences in developmental periods between males and females. For example, Parker and Clarke [26] described an accelerated development of stride length and stride width in males, although the main pattern of gait topography was similar. The main characteristics of skilled walking were highly recognizable and comparable among pups, however, suggesting that sexual dimorphisms in the measured behaviours, if present, are rather subtle.

6. Conclusion

The new rung bridge stepping task was found to be a useful and sensitive task to investigate discrete changes in fine and gross motor skill during rat ontogeny. The data show that rat pup motor development progresses in six distinguishable stages. At each stage of development, specific and reliable motor behaviours occur. Accordingly, Eilam [2] hypothesized that the ontological development of gait in rodents supports a uniformity of phylogenetic development. Many of the initial motor behaviours of the rat are arguably ontologically similar to primitive forms of quadruped locomotion. For example, the first ambulatory movements of the rat are analogous to that of a salamander, whose limbs project lateral to the body, articulate in an abduct/adduct pattern and are not used to elevate the salamander off the ground.

In summary, the present data support the presence of a rostral–caudal as well as ventral–dorsal gradient during nervous system development [6]. If, as posited by Teitelbaum et al. [27] and Cramer and Chopp [28], recovery recapitulates ontogeny, this research is invaluable to scientists using rat models to study compensatory movements after brain injury.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Preterm Birth and Healthy Outcomes Team #200700595. AS and GM were supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

References

- 1.Altman J, Sudarshan K. Postnatal development of locomotion in the laboratory rat. Anim Behav. 1975;23:896–920. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(75)90114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eilam D. Postnatal development of body architecture and gait in several rodent species. J Exp Biol. 1997;200:1339–50. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.9.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stelzner DJ. The role of descending systems in maintaining intrinsic spinal function: a developmental approach. In: Sjolund B, Bjorklund A, editors. Brainstem Control of Spinal Mechanisms. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1982. pp. 297–322. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamon M. The early development of motor control in neonate rat. CR Palevol. 2006;5:657–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiehn O. Locomotor circuits in the mammalian spinal cord. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:279–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nornes HO, Das GD. Temporal pattern of neurogenesis in the spinal cord of rat. I. An autoradiographic study—time and sites of origin and migration and settling patterns of neuroblasts. Brain Res. 1974;73:121–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)91011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altman J, Bayer SA. The Development of the Rat Spinal Cord. New York: Springer Verlag; 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metz GAS, Whishaw IQ. Cortical and subcortical lesions impair skilled walking in the ladder rung walking test: a new task to evaluate fore- and hindlimb stepping, placing, and co-ordination. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:169–79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farr TD, Liu L, Colwell KL, Whishaw IQ, Metz GA. Bilateral impairments after unilateral motor cortex injury: a new test strategy for analysis of skilled limb movements in neurological mouse models. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;153:104–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metz GA, Whishaw IQ. The ladder rung walking task: a scoring system and its practical application. J Vis Exp. 2009:28. doi: 10.3791/1204,pii:1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunner JA, Altman J. Swimming in the rat: analysis of locomotor performance in comparison to stepping. Exp Brain Res. 1980;40:374–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00236146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown MC, Jansen JKS, van Essen D. Polyneuronal innervation of skeletal muscle in new-born rats and its elimination during maturation. J Physiol. 1976;261:387–422. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson WJ, Soileau LC, Balice-Gordon RJ, Sutton LA. Selective innervation of types of fibres in developing rat muscle. J Exp Biol. 1987;132:249–63. doi: 10.1242/jeb.132.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreyer DJ, Jones EH. Topographic sequence of outgrowth of corticospinal axons in the rat: a study using retrograde axonal labeling with fast blue. Brain Res. 1988;466:89–101. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curfs MHJM, Gribnau AAM, Dederen PJWC. Direct cortico-motoneuronal synaptic contacts are present in the adult rat cervical spinal cord and are first established at postnatal day 7. Neurosci Lett. 1996;205:123–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12396-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schreyer DJ, Jones EG. Growing corticospinal axons by-pass lesions of neonatal rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1983;9:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamon M, Maloum I, Riviere G, Bruguerolle B. Air-stepping in neonatal rats: a comparison of L-dopa injection and olfactory stimulation. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:1014–21. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.6.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westerga J, Gramsbergen A. Structural changes of the soleus and the tibialis anterior motoneuron pool during development in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319:406–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westerga J, Gramsbergen A. Development of the EMG of the soleus muscle in the rat. Dev Brain Res. 1994;80:233–43. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hultborn H, Nielsen JB. Spinal control of locomotion—from cat to man. Acta Physiol. 2007;189:111–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundberg A. Norwegian Academy of Sciences and Letters. The Nasen Memorial Lecture V. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 1969. Reflex control of stepping; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metz GA, Jadavji NM, Smith LK. Modulation of motor function by stress: a novel concept of the effects of stress and corticosterone on behavior. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein A, Wessolleck J, Papazoglou A, Metz GA, Nikkhah G. Walking pattern analysis after unilateral 6-OHDA lesion and transplantation of foetal dopaminergic progenitor cells in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199:317–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schallert T, Woodlee MT, Fleming SM. Disentangling multiple types of recovery from brain injury. In: Krieglstein J, Klumpp S, editors. Pharmacology of Cerebral Ischemia. Stuttgart: Medpharm Scientific Publishers; 2002. pp. 201–16. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muir GD. Early ontogeny of locomotor behaviour: a comparison between altricial species and precocial animals. Brain Res Bull. 2000;5:719–26. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker AJ, Clarke KA. Gait topography in rat locomotion. Physiol Behav. 1990;48:41–7. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teitelbaum P, Cheng MF, Rozin P. Development of feeding parallels its recovery after hypothalamic damage. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1969;67:430–41. doi: 10.1037/h0027288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cramer SC, Chopp M. Recovery recapitulates ontogeny. Trends Neurosci. 2000:23265–71. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01562-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fady JC, Jamon M, Clarac F. Early olfactory-induced rhythmic limb activity in the newborn rat. Dev Brain Res. 1998;108:111–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamon M, Clarac F. Early walking in the neonatal rat: a kinematic study. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1218–28. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Child CM. The physiological significance of the cephalocaudal differential in vertebrate development. Anat Rec. 1925;31:369–83. [Google Scholar]