Abstract

Background

Mexican-born children living in the US have a lower prevalence of asthma than other US children. While children of Mexican descent near the Arizona-Sonora border are genetically similar, differences in environmental exposures might result in differences in asthma prevalence across this region.

Objective

To determine if the prevalence of asthma and wheeze in these children varies across the AZ-Sonora border.

Methods

The International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Children written and video questionnaires were administered to 1753 adolescents from five middle schools: Tucson (school A), Nogales, AZ (schools B, C), and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico (schools D, E). Prevalence of asthma and symptoms was compared, with analyses in the AZ schools limited to self-identified Mexican-American students.

Results

Compared with the Sonoran reference school E, the adjusted odds ratio for asthma was significantly higher in US schools A (OR 4.89, 95%CI 2.72-8.80), B (3.47, 1.88-6.42), and C (4.12, 1.78-9.60). The adjusted odds ratio for wheeze in the past year was significantly higher in schools A (2.19, 1.20-4.01) and B (2.67, 1.42-5.01) on the written questionnaire and significantly higher in A (2.13, 1.22-3.75), B (1.95, 1.07-3.53) and Sonoran school D (2.34, 1.28-4.30) on the video questionnaire compared with school E.

Conclusion

Asthma and wheeze prevalence differed significantly between schools and was higher in the US. Environmental factors that may account for these differences could provide insight into mechanisms of protection from asthma.

Keywords: Asthma, Wheezing, Environment, Mexican Americans, Socioeconomic Factors, Bacterial Load

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic disease for which an individual’s early life exposures may be critically important as preventive or modulating factors1. Although the prevalence of asthma in Hispanic children across the United States (US) is similar to the prevalence of asthma in non-Hispanics, there is variability among Hispanics, with the risk of asthma in children of Mexican descent being very low compared with other subgroups2-5. Evidence supports an effect of nativity on this risk6. Children who were born in and emigrated from Mexico have been shown to have lower prevalence of asthma than Mexican-American children born in the US6-11. Degree of acculturation, age of immigration to the US, immigrant generation, and duration of time lived in the US have all been associated in a dose-dependent manner with the prevalence of asthma9,12-15. Much of this prevalence data, however, is acquired through national surveys. In contrast, cross-sectional analyses of socio-economically distinct but geographically and ethnically similar regions can provide unique insight into the impact of social and economic factors on disease prevalence16.

The US-Mexico border spans more than 3,000 kilometers, with the “border region” extending 100 kilometers on each side of the border, as defined by the La Paz Agreement. Most of the region’s population reside in 14 city pairs straddling the border, one of which is comprised of the sister cities of Nogales, Arizona, USA, and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. Once a large shared city and environment where people easily traversed the US-Mexico border, this region has gradually separated into discrete cities following the adoption of stricter border controls. Nogales, Sonora is the larger city, housing 90% of the region’s population (approx. 241,129). While the population of Nogales, AZ is 95% Hispanic, societal infrastructure is consistent with US standards and contrasts with that of Sonora in sanitation, access to clean drinking water, access to health care, and traffic density. The extent to which the border partition has impacted disparities between the environments, populations, and disease prevalence is not yet clear17. Tucson, Arizona is located approximately 110 kilometers north of Nogales, AZ along the Interstate 19 corridor. While the general population of Tucson is reported to be 41.6% Hispanic18, some census tracts within Tucson are over 90% Hispanic.

We hypothesized that as a result of environmental and/or social differences in these areas, the prevalence of asthma is lower in Sonora than in Arizona, and that these differences would be detected across this region, despite the proximity of the areas studied. We therefore sought to compare the prevalence of asthma and asthma symptoms among middle school aged children in three cities within this unique border location: Tucson, Arizona; Nogales, Arizona; and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico.

Methods

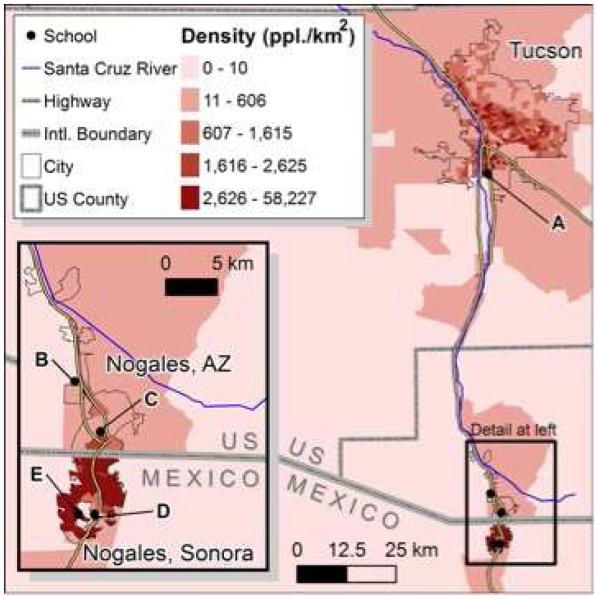

We conducted a cross-sectional study of asthma and asthma symptoms among adolescents from five schools near the US-Mexico border: one school in Tucson, Arizona (school “A”), two in Nogales, Arizona (schools “B” and “C”); and two in Nogales, Sonora (schools “D” and “E”) (Figure 1). The Arizona schools were chosen for the high proportion of Hispanic children. The schools in Sonora were chosen to represent children from higher (school D) and lower (school E) socioeconomic status. Characteristics of each school are shown in Table 1. In order to capture students in the 13-14 year old age range, 7th and 8th grades were invited to participate. Parental consent was obtained through forms or school-facilitated opt-out notifications, and a statement of assent read before questionnaires were distributed. Surveys were completed during a four-week span in late Spring 2015, during a single school day for each school, except for the Tucson school, which was surveyed over two days. Study documents were translated by a professional translator familiar with regional Spanish from English to Spanish, and then back-translated by our bilingual study staff and investigators. The study was approved and monitored by the University of Arizona Human Subjects Protection Program.

Figure 1.

Map of school location with population density (people per square kilometer) by quintiles.

Table 1.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of each middle school.

|

Total School

Enrollment, all grades |

Ethnicity | Estimate of Socioeconomic status | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona Schools | |||

| A | 931 | 89% Hispanic 10% Native American <1% White |

Free & Reduced Lunch 84% |

| B | 783 | 98% Hispanic <1% Native American <1% White |

Free & Reduced Lunch 100% |

| C | 621 | 98% Hispanic <1% Native American <1% White |

Free & Reduced Lunch 100% |

| Sonora Schools | |||

| D | 593 | n/a | High Urbanization Low Marginalization 15 students/computer 16 students/ teacher |

| E | 463 | n/a | Low Urbanization High Marginalization 31 students/computer 17 students/teacher |

Written questionnaire

Survey questions were taken directly from the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Children (ISAAC), a questionnaire to assess asthma prevalence which has been validated in multiple populations around the world19-23. Children were asked to report if they “ever had asthma”, “ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest”, and “wheezing in the past 12 months”. Subjects also recorded age, gender and primary language spoken at home. In US schools, questionnaires were offered in both English and Spanish. In Mexican schools, questionnaires were offered in Spanish.

Video questionnaire

The ISAAC video questionnaire was administered to all participants. Students were instructed to watch five separate scenarios depicting asthma symptoms. After each scene, the students were instructed to answer the corresponding question of whether they have had these symptoms, and whether and how frequently the symptoms occurred in the past 12 months. Wheeze was defined based on responses to the first scenario, which depicts a person wheezing at her desk. Questions were asked in English in Arizona schools and Spanish in Sonora.

Dust Collection

Dust sampling methods are reported in the supplemental repository.

Bacterial DNA extraction and quantitation

Bacterial DNA extraction and quantitation methods are reported in the supplemental repository.

Statistical Methods

Demographic characteristics by school were compared by Fisher’s exact test and one-way analysis of variance. Differences in asthma prevalence and reported wheeze were initially compared across schools by Fisher’s exact. We then calculated odds ratios for asthma and wheeze using mixed-effects logistic regression models in order to adjust for age and gender, and to control for within class-period correlation. The strength of agreement between written and video questionnaires was assessed by kappa coefficient, defined as24: poor (<0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), good (0.61–0.80), or very good (0.81–1.0). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. All tests were performed using Stata version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 1753 students participated in this survey. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 2. A high proportion of students from Arizona schools self-identified as Hispanic of Mexican origin (Table 2). All participants in Mexico were assumed to be Hispanic of Mexican origin. As our hypothesis focused on students of Mexican origin, all further analyses exclude the US students who did not identify as being of Mexican origin. Table 2 shows the distribution of languages spoken in the home for each school. The proportion of households speaking English without Spanish was greater for schools in the US, with the highest proportion in the school located furthest from the US-Mexico border.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants, by school.

|

Total

Participants |

Gender | Age |

Hispanic,

Mexican Origin |

Languages spoken at home

(Hispanic, Mexican Origin only) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n* | Male | mean (range) |

% (n) | English, no Spanish |

English & Spanish |

Spanish, no English |

|

|

Tucson

A |

783 |

47.6 (369/776) |

13.4 (11-16) |

79.9 (622/779) |

34.3 (211/615) |

44.2 (272/615) |

21.5 (132/615) |

|

Nogales, AZ

B C |

384 72 |

50.5 (191/378) 37.5 (27/72) |

13.3 (12-16) 12.7 (10-16) |

93.2 (357/383) 81.9 (59/72) |

14.8 (51/345) 12.1 (7/58) |

55.4 (191/345) 70.7 (41/58) |

29.9(103/345) 17.2 (10/58) |

|

Nogales, Sonora

D E |

302 212 |

45.0 (130/289) 52.3 (104/199) |

13.6 (12-16) 13.5 (11-15) |

NA NA |

2.1 (6/284) 0.0 (0/198) |

4.9 (14/284) 2.0 (4/198) |

92.7 (265/284) 98.0 (194/198) |

| p-values | p=0.15 | p<0.001** | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | |||

Unless indicated, values are expressed as percentage, with number per total responses received.

Total participants n reflects the number of students in each classroom on the day of survey administration. Reported denominators for each variable reflect the number of students responding to that question.

P-values assessed by ANOVA. All groups were significantly different from each other in post-hoc testing. NA – Hispanic ethnicity and of Mexican origin question not applicable to children in Sonoran schools

Rates of reported asthma and asthma symptoms from each school are displayed in Table 3. Children in Arizona schools reported significantly higher rates of ever having asthma compared to children in Sonora schools (25.8% vs 8.4%, respectively, p<0.001). This was also true for wheeze in the past year as reported on the written questionnaire (16.9% vs 9.6%, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Student report of ever having asthma and wheeze in the past year.

| Written Questionnaire | Video Questionnaire |

Agreement of

Written, Video Wheeze |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Asthma, ever | Wheeze, past year | Wheeze, past year | ||

|

|

||||

| School | % (proportion) | % (proportion) | %(proportion) | Kappa, p |

|

Tucson

A |

28.0 (169/603) |

16.0 (97/603) |

17.3(106/613) |

0.45, <0.001 |

|

| ||||

|

Nogales, AZ

B C |

22.0 (76/346) 26.0 (14/54) |

18.6 (66/354) 14.3 (8/56) |

15.7(56/357) 14.0 (8/57) |

0.45, <0.001 0.41, 0.001 |

|

| ||||

|

Nogales, Sonora

D E |

9.6 (28/292) 6.8 (14/206) |

9.5 (28/295) 7.7 (16/209) |

18.5 (56/302) 8.0 (17/212) |

0.29, <0.001 0.26, <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 | |

A slightly different pattern was evident from the video questionnaire. While students in the Arizona schools and school E reported similar rates of wheeze in the past year to those reported on the written questionnaire, children in school D reported double the rate of wheeze in response to the wheezing video scene (Table 3) compared to what they reported on the written questionnaire. While rates of wheeze reported on the video questionnaire are higher in the US compared with Mexico, this was not statistically significantly different (16.5% vs 14.2%, respectively, p=0.27). The interrater agreement (kappa value) between an affirmative response to the written and video questionnaire on the wheeze question was moderate for schools A and B, and only fair in schools C, D, and E.

The odds ratios for asthma and wheeze in each school, adjusting for age, gender, and class-period, are presented in Table 4, using school E in Sonora as a reference. Schools A and B had higher odds ratios for asthma and wheeze in the past year as reported both on written and video questionnaires. School C had a higher odds ratio for reported asthma, compared with school E. Interestingly, the odds ratio for wheeze in the past year on the video questionnaire was also significantly higher for school D.

Table 4.

Odds ratio from mixed-effect logistic regression models for ever having asthma and wheeze in the past year.

| Written Questionnaire | Video Questionnaire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Asthma, ever | Wheeze, past year | Wheeze, past year | ||||

|

|

||||||

| School | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p |

|

Tucson

A |

4.89 (2.72-8.80) |

<0.001 |

2.19 (1.20-4.01) |

0.01 |

2.13 (1.22-3.75) |

0.008 |

|

| ||||||

|

Nogales, AZ

B C |

3.47 (1.88-6.42) 4.13 (1.78-9.60) |

<0.001 0.001 |

2.67 (1.42-5.01) 1.67 (0.63-4.42) |

0.002 0.30 |

1.95 (1.07-3.53) 1.60 (0.63-4.07) |

0.03 0.32 |

|

| ||||||

|

Nogales,

Sonora D E |

1.36 (0.68-2.71) ref |

0.32 ref |

1.26 (0.62-2.54) ref |

0.52 |

2.34 (1.28-4.30) ref |

0.006 ref |

|

| ||||||

| P-value | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.058 | |||

Adjustment for language spoken in the home was not performed in the logistic models shown in Table 4, because there was no variability of language spoken in the Mexican schools. However, among US participants, the OR for asthma was 1.71 (1.14-2.55, p=0.009) for those who spoke English only and 0.88 (0.61-1.28, p=0.52) for those speaking both English and Spanish, compared to those who spoke Spanish only in the home (Supplemental table 2). Similarly, wheeze in the past year showed a similar language gradient among participants in the US, with odds for ever wheeze on the written questionnaire being 1.88 (1.15-3.08, p=0.01) and 1.30 (0.82-2.05, p=0.27), for those speaking English only or both English and Spanish, respectively, compared to exclusive Spanish speakers. Interrater statistics for agreement between the written and video questionnaire by home languages were moderate for all groups, with kappa of 0.53 for English no Spanish, 0.41 for English and Spanish, and 0.42 for Spanish no English.

The average mass of dust per square meter varied by school. The dust load, measured as grams of dust per square meter, was markedly lower in Arizona schools A and B compared with schools D and E (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Table 2). The bacterial load, measured as bacterial DNA copies per square meter, was substantially higher in schools D and E (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

Our study shows a lower prevalence of asthma and wheeze reported in children of Mexican origin attending school in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico compared with Nogales, Arizona and Tucson, Arizona. Rates of lifetime asthma were threefold higher in children from the Arizona schools. Symptoms reported in the past year, a marker of current asthma, were also substantially higher in children from Arizona compared with those from Sonora when reported in response to the written questionnaire.

Our results are consistent with the few studies of asthma in the US-Mexico border zone that collectively suggest higher rates of asthma and allergic disease on the US side of the Texas-Mexico border 14,25, and along the California-Mexico border 26, particularly among those who are Hispanic. In 1996, Stephen et al27 compared respiratory symptoms in primary school-aged children in Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora. In this study, the frequency of wheeze was significantly higher in the Arizonan students, which is similar to our findings. A high rate of asthma hospitalization has also been observed on the US side compared with the Mexican side of the border, and reducing this rate is an objective of both the Healthy Border 2010 initiative28 and the Healthy Border 2020 initiative29.

While the overall rate of asthma among children in Mexico is estimated at 13%30, rates of asthma in Mexico vary widely by geographic region, even when utilizing the same ISAAC questionnaire that was used in this study31-34. This regional variability supports the hypothesis that environmental and/or sociocultural factors differentially impact the development of asthma among groups in Mexico. Further, this variability creates the potential to identify low risk areas, and to investigate the lifestyle characteristics which are associated with lower asthma prevalence, as has been done for farming communities in Europe1,35,36.

Tucson and both cities of Nogales are officially grouped as a combined statistical area, based on their social and economic ties37. However, there are a number of social and environmental differences between the Arizona cities and Nogales, Sonora. There has been substantial population growth in Nogales, Sonora, estimated at 40% from 2000-201038, compared to only 20% in the Arizona region37. Population density is also substantially greater in Nogales, Sonora (Figure 1): The average number of people per household is 2.5 in Tucson, 3.1 in Nogales, Arizona, and 3.8 in Nogales, Sonora39,40. The rapid population growth in Nogales, Sonora has resulted in increased traffic and development of neighborhoods that lack sanitation and access to clean drinking water41,42. The neighborhood which feeds into school E is one of these, with only 20% of the population having access to sewers or sanitation43,44. Further, air pollution as a result of increased traffic and industrial emissions is also higher on the Mexican side of Nogales than on the US side 45. There are multiple other differences between the communities (e.g. prenatal care46,47, breastfeeding48 and cesarean-section rates49), which may contribute to differences in prevalence of asthma and wheeze. Bacterial exposure, utilizing endotoxin measurement as proxy, has been previously inversely associated with atopy and asthma, particularly in farming communities50,51. The notable differences of dust load and bacterial load identified among the schools in this study, while a rough estimate of the overall environmental exposures of these children, likely reflect meaningful differences in community exposures. In the context of different asthma rates among the schools, this is consistent with the possibility that environmental microbial exposures may impact asthma risk and development36,52.

The difference in asthma reporting and symptoms between the two Nogales, Sonora schools may reflect differences in exposures and populations represented in those schools. While children in both schools have equal access to medical care through state health systems, schools D and E represent very different populations and environments within the city of Nogales, Sonora. School D is physically located in the middle of the maquiladora park (i.e. industrial complex with multiple manufacturing factories), where there may be industrial emissions1. This school also functions as a magnet school, attracting children of higher socio-economic status who live in neighborhoods across the city, requiring separate application, entrance examinations, and external endorsement for admission. In contrast, school E is in a colonia that originated as a squatters’ settlement for maquiladora workers. This colonia has limited access to sanitation and infrastructure despite a very high population density (Figure 1), and is highly marginalized as measured by the Mexican National Council for Population53. Social differences are also evident in the higher proportion of English spoken in the home among children of school D, compared with those of school E. The differences in reported asthma symptoms between these schools may therefore reflect both environmental and socioeconomic differences.

One limitation of this study is the reliance on self-reporting of asthma and symptoms. This is a limitation of all studies utilizing the ISAAC questionnaire, which was validated in mixed ethnic populations23. Children with a personal or family history of asthma may better understand the asthma-specific terms used in the survey. However, health care in Nogales Sonora is available to everyone through one of three state run health care systems. In fact, residents of Arizona are more likely to lack access to healthcare, and even under the Affordable Care Act, Hispanics in Arizona are among the most under-enrolled groups54. Additionally, schools A, B, and C are in medically underserved areas with limited access to care. Therefore, rates of reported asthma in Arizona in this study may be underestimated.

An assumption underlying our hypothesis in conducting this study is that the children surveyed were born in the catchment area for their school. In fact, some students who live in Mexico cross the border to attend school in Arizona and some Arizona students may have been born or raised in Mexico and immigrated to the US. Asking children where they were born would have provided this information. However, given the current political climate in Arizona regarding illegal immigration55, we opted not to ask about birthplace because it may have made participants feel uncomfortable despite the confidential and de-identified nature of the questionnaires, particularly in a public school setting. In either case, misclassification of birthplace would bias toward no difference between the cities. Maternal nativity may affect asthma reporting, with children of foreign-born mothers being less likely to report asthma56, but this too would bias toward no difference. Further, while we assume genetic similarity among the participants, we acknowledge the lack of information documenting genetic admixture.

Language spoken in the home may be utilized as a surrogate marker of acculturation and shows a predicted gradient of English to Spanish from Tucson to Mexico (Table 1), supporting the previously reported effect of acculturation on regression to the local mean of disease status6. Within the Arizona schools, we see a gradient of asthma prevalence that varies by language spoken in the home.

The lack of concordance between response to the written and video questionnaires identified in this study, being only fair to moderate, is consistent with previously published literature for ISAAC 23,57. While ISAAC has been utilized in Spanish-speaking or Latin-American countries58,59, with sensitivity and specificity of the wheeze question at 44.2% and 90%, respectively58, one ISAAC validation study noted relative underreporting of wheeze in Spanish-speaking adolescents when compared with a video vignette depicting a child wheezing60. Wheeze may however be the best symptom indicator of asthma in Mexican schoolchildren30. With binational and bilingual studies such as this, the terminology used to assess asthma symptoms may not translate accurately. Specifically, the term “wheeze” may be misunderstood in non-English languages61. We recognized that our results may therefore be confounded by translation and choice of words. The differences in video questionnaire results between schools D and E may also have resulted from methodologic issues: Administration of the video questionnaire in school D was challenging due to lack of student engagement, behavioral issues, and technical difficulties that made it hard to hear the video.

This study shows that asthma prevalence reflects a gradient spanning Tucson to Sonora, with rates particularly low in regions of low socioeconomic status in Sonora. These differences, in a population of adolescents from similar ethnic background, suggest that environmental factors contribute to this gradient in a complex way, potentially mediated by socioeconomic status, education, and acculturation. Further study is warranted to assess the environmental and social factors that contribute to these differences in prevalence in a single population of common ancestry who live on both sides of the US/Mexico border.

Supplementary Material

Highlights Box.

What is already known about this topic? Rates of reported asthma and wheeze differ significantly by schools across the US/Mexico border. This difference may be attributable in part to environmental influences.

What does this article add to our knowledge? Using the ISAAC questionnaire, we found a significantly higher prevalence of asthma in school children of Mexican descent in Arizona, compared with those in Sonora, Mexico despite proximity and common ancestry.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? This difference in asthma prevalence may be attributable in part to environmental influences. Understanding these differences may identify modifiable risk factors for asthma.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely thankful to the school leadership for their support of this study, and to the students and their families for their participation. We would also like to thank James Roebuck for designing and scanning the questionnaires; Celina Valencia BA, Nicolas Galvez Lopez MPH for helping with data collection; Aimee Snyder MPH, who recruited and coordinated data collection volunteers, and those volunteers: Rachelle Begay MPH, Shelby Calvillo, Briana Chavez, Marie Culver, Jayelle Harrison, Ashley Lowe, Emily Waldron MPH .

Grant funding: This work was supported in part by HRSA/MCHB T76MC04925, P30 ES006694, K25 HL103970, T32 ES007091 and the México Section of the US-Mexico Border Health Commission.

Abbreviations

- ISAAC

International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Children

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: TFC and PIB contributed equally to writing the manuscript. TFC, PIB, JR, and DAS participated in data analysis. PIB, JR, CBR, LBG, DV, MG and ALW participated in data collection. YOV, OP conducted experiments and participated in experimental design and writing. MH, FDM, and all other authors participated in the conception and design of the study, data interpretation, revisions of draft for critically important intellectual content, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- 1.Bousquet J, Gern JE, Martinez FD, et al. Birth cohorts in asthma and allergic diseases: report of a NIAID/NHLBI/MeDALL joint workshop. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1535–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canino G, Koinis-Mitchell D, Ortega AN, McQuaid EL, Fritz GK, Alegría M. Asthma disparities in the prevalence, morbidity, and treatment of Latino children. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(11):2926–2937. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001-2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(94):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leong AB, Ramsey CD, Celedón JC. The challenge of asthma in minority populations. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;43(1-2):156–183. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moorman JE, Zahran H, Truman BI, Molla MT, (CDC) CfDCaP Current asthma prevalence - United States, 2006-2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(Suppl):84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr RG, Aviles-Santa L, Davis SM, et al. Pulmonary Disease and Age at Immigration Among Hispanics: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1211OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eldeirawi K, McConnell R, Freels S, Persky VW. Associations of place of birth with asthma and wheezing in Mexican American children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holguin F, Mannino DM, Antó J, et al. Country of birth as a risk factor for asthma among Mexican Americans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):103–108. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-143OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eldeirawi KM, Persky VW. Associations of acculturation and country of birth with asthma and wheezing in Mexican American youths. J Asthma. 2006;43(4):279–286. doi: 10.1080/0277090060022869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iqbal S, Oraka E, Chew GL, Flanders WD. Association between birthplace and current asthma: the role of environment and acculturation. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 1):S175–182. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subramanian SV, Jun HJ, Kawachi I, Wright RJ. Contribution of race/ethnicity and country of origin to variations in lifetime reported asthma: evidence for a nativity advantage. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):690–697. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eldeirawi KM, Persky VW. Associations of physician-diagnosed asthma with country of residence in the first year of life and other immigration-related factors: Chicago asthma school study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99(3):236–243. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60659-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cagney KA, Browning CR, Wallace DM. The Latino paradox in neighborhood context: the case of asthma and other respiratory conditions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(5):919–925. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svendsen ER, Gonzales M, Ross M, Neas LM. Variability in childhood allergy and asthma across ethnicity, language, and residency duration in El Paso, Texas: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health. 2009;8:55. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balcazar AJ, Grineski SE, Collins TW. The Hispanic health paradox across generations: the relationship of child generational status and citizenship with health outcomes. Public Health. 2015;129(6):691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haahtela T, Laatikainen T, Alenius H, et al. Hunt for the origin of allergy - comparing the Finnish and Russian Karelia. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(5):891–901. doi: 10.1111/cea.12527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casey ES, Watkins M. Up Against the Wall: Re-Imagining the U.S.-Mexico Border. University of Texas Press; Austin, Texas: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.United States Census Bureau QuickFacts. 2016 http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/0477000,0477000. Available at. Accessed January 21, 2016.

- 19.Shaw RA, Crane J, Pearce N, et al. Comparison of a video questionnaire with the IUATLD written questionnaire for measuring asthma prevalence. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22(5):561–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw RA, Crane J, O'Donnell TV, Lewis ME, Stewart B, Beasley R. The use of a videotaped questionnaire for studying asthma prevalence. A pilot study among New Zealand adolescents. Med J Aust. 1992;157(5):311–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai CK, Chan JK, Chan A, et al. Comparison of the ISAAC video questionnaire (AVQ3.0) with the ISAAC written questionnaire for estimating asthma associated with bronchial hyperreactivity. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997;27(5):540–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(3):483–491. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson PG, Henry R, Shah S, et al. Validation of the ISAAC video questionnaire (AVQ3.0) in adolescents from a mixed ethnic background. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30(8):1181–1187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman D. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman & Hall/CRC; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos IN, Davis LB, He Q, May M, Ramos KS. Environmental risk factors of disease in the Cameron Park Colonia, a Hispanic community along the Texas-Mexico border. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(4):345–351. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.English PB, Von Behren J, Harnly M, Neutra RR. Childhood asthma along the United States/Mexico border: hospitalizations and air quality in two California counties. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1998;3(6):392–399. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891998000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephen GA, McRill C, Mack MD, O'Rourke MK, Flood TJ, Lebowitz MD. Assessment of respiratory symptoms and asthma prevalence in a U.S.-Mexico border region. Arch Environ Health. 2003;58(3):156–162. doi: 10.3200/AEOH.58.3.156-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Commission. US-MBH Healthy Border 2010. http://www.borderhealth.org/files/res_63.pdf Accessed November 9, 2015.

- 29.Commission U-MBH Healthy Border 2020: A Prevention and Health Promotion Initiative. 2015 Accessed November 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mancilla-Hernández E, Medina-Ávalos M, Barnica-Alvarado R, Soto-Candia D, Guerrero-Venegas R, Zecua-Nájera Y. Prevalence of Asthma and Determinants of Symptoms as Risk Indicators. Rev Alerg Mex. 2015 Oct-Dec;62(4):271–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barraza-Villarreal A, Sanin-Aguirre LH, Tellez-Rojo MM, Lacasana-Navarro M, Romieu I. Prevalence of asthma and other allergic diseases in school children from Juarez City, Chihuahua. Salud Publica Mex. 2001;43(5):433–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tatto-Cano MI, Sanin-Aguirre LH, Gonzalez V, Ruiz-Velasco S, Romieu I. Prevalence of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in school children in the city of Cuernavaca, Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 1997;39(6):497–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendoza-Mendoza A, Romero-Cancio JA, Pena-Rios HD, Vargas MH. Prevalence of asthma in schoolchildren from the Mexican city Hermosillo. Gac Med Mex. 2001;137(5):397–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rojas Molina N, Legorreta Soberanis J, Olvera Guerra F. Prevalence and asthma risk factors in municipalities of the State of Guerrero, Mexico. Rev Alerg Mex. 2001;48(4):115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Illi S, Depner M, Genuneit J, et al. Protection from childhood asthma and allergy in Alpine farm environments-the GABRIEL Advanced Studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(6):1470–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.013. e1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ege MJ, Mayer M, Normand AC, et al. Exposure to environmental microorganisms and childhood asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):701–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bureau USC Arizona Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) and Counties. Accessed Accessed: November 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.EA C Carondelet Holy Cross Hospital Community Health Needs Assessment, Santa Cruz County, Arizona. 2013:1–102. Accessed Accessed: November 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bureau USC 2009-2013 ACS 2005 Year Summary Files and Data Profiles. Accessed Accessed: November 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.(INEGI) INdEyG Accessed Accessed:November 17, 2015.

- 41.Norman L, Feller M, Guertin D. Forecasting urban growth across the United States–Mexico border. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems. 2009;(33):150–159. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norman L, Donelson A, Pfeifer E, Lam A. Colonia development and land use change in Ambos Nogales, United States-Mexican Border. USGS Report 2066-11122006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Austin D, Trujillo F. Composting Toilets and Water Harvesting: Alternatives for Conserving and Protecting Water in Nogales, Sonora. Border Environment Cooperation Commission, United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilder M, Scott C, Pineda-Pablos N, Varady R, Garfin G. Moving Forward from Vulnerability to Adaptation: Climate Change, Drought, and Water Demand in the Urbanizing Southwestern United States and Northern Mexico. Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy; The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ.: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith LA, Mukerjee S, Monroy GJ, Keene FE. Preliminary assessments of spatial influences in the Ambos Nogales region of the US-Mexican border. Sci Total Environ. 2001;276(1-3):83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(01)00773-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castrucci BC, Piña Carrizales LE, D'Angelo DV, et al. Attempted breastfeeding before hospital discharge on both sides of the US-Mexico border, 2005: the Brownsville-Matamoros Sister City Project for Women's Health. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(4):A117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frank R, Heuveline P. A crossover in Mexican and Mexican-American fertility rates: Evidence and explanations for an emerging paradox. Demogr Res. 2005;12(4):77–104. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2005.12.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harley K, Stamm NL, Eskenazi B. The effect of time in the U.S. on the duration of breastfeeding in women of Mexican descent. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(2):119–125. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0152-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McDonald JA, Mojarro Davila O, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ. Cesarean birth in the border region: a descriptive analysis based on US Hispanic and Mexican birth certificates. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(1):112–120. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simpson A, John SL, Jury F, et al. Endotoxin exposure, CD14, and allergic disease: an interaction between genes and the environment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(4):386–392. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1380OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braun-Fahrlander C, Riedler J, Herz U, et al. Environmental exposure to endotoxin and its relation to asthma in school-age children. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):869–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujimura KE, Demoor T, Rauch M, et al. House dust exposure mediates gut microbiome Lactobacillus enrichment and airway immune defense against allergens and virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(2):805–810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310750111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Secretaria De Gobernacion EUM Indices de Marginacion. 2010 Accessed December 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evaluation OotASfPa Survey Data on Health Insurance Coverage for 2013 and 2014. Services UDoHaH, edOctober 31, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simpson I. Judge upholds Arizona's 'Show your papers' Immigration Law. Reuters; [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camacho-Rivera M, Kawachi I, Bennett GG, Subramanian SV. Revisiting the Hispanic Health Paradox: The Relative Contributions of Nativity, Country of Origin, and Race/Ethnicity to Childhood Asthma. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9974-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hong SJ, Kim SW, Oh JW, et al. The validity of the ISAAC written questionnaire and the ISAAC video questionnaire (AVQ 3.0) for predicting asthma associated with bronchial hyperreactivity in a group of 13-14 year old Korean schoolchildren. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18(1):48–52. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lukrafka JL, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB, Picon RV, Fischer GB, Fuchs FD. Performance of the ISAAC questionnaire to establish the prevalence of asthma in adolescents: a population-based study. J Asthma. 2010;47(2):166–169. doi: 10.3109/02770900903483766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mata Fernández C, Fernández-Benítez M, Pérez Miranda M, Guillén Grima F. Validation of the Spanish version of the Phase III ISAAC questionnaire on asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2005;15(3):201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crane J, Mallol J, Beasley R, Stewart A, Asher MI, group ISoAaAiCPIs Agreement between written and video questions for comparing asthma symptoms in ISAAC. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(3):455–461. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00041403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ellwood P, Williams H, Aït-Khaled N, Björkstén B, Robertson C, Group IPIS Translation of questions: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) experience. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(9):1174–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.