Abstract

Francisella tularensis (Ft) is a category A biothreat agent for which there is no Food and Drug Administration-approved vaccine. Ft can survive in a variety of habitats with a remarkable ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions. Furthermore, Ft expresses distinct sets of antigens (Ags) when inside of macrophages (its in vivo host) as compared to those grown in vitro with Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB). However, in contrast to MHB-grown Ft, Ft grown in Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) more closely mimics the antigenic profile of macrophage-grown Ft. Thus, we anticipated that when used as a vaccine, BHI-grown Ft would provide better protection compared to MHB-grown Ft, primarily due to its greater antigenic similarity to Ft circulating inside the host (macrophages) during natural infection. Our investigation, however, revealed that inactivated Ft (iFt) grown in MHB (iFt-MHB) exhibited superior protective activity when used as a vaccine, as compared to iFt grown in BHI (iFt-BHI). The superior protection afforded by iFt-MHB compared to that of iFt-BHI was associated with significantly lower bacterial burden and inflammation in the lungs and spleens of vaccinated mice. Moreover, iFt-MHB also induced increased levels of Ft-specific IgG. Further evaluation of early immunological cues also revealed that iFt-MHB exhibits increased engagement of Ag-presenting cells including increased iFt binding to dendritic cells, increased expression of costimulatory markers, and increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Importantly, these studies directly demonstrate that Ft growth conditions strongly impact Ft vaccine efficacy and that the growth medium used to produce whole cell vaccines to Ft must be a key consideration in the development of a tularemia vaccine.

Keywords: APC, whole cell-based vaccines, Francisella tularensis, costimulatory molecules, growth factors

Introduction

Whole cell-based vaccines are preferred in the absence of well-defined protective immunogens. In addition, whole cell-based vaccines provide a broad range of potential protective antigens (Ags) and immune stimulatory molecules, which can include proteins, polysaccharides, and pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules (PAMPs). In the absence of an identified protective Ag, directing the immune response toward an array of Ags that the host is likely to encounter during a natural infection maximizes the potential for a protective immune response to be generated upon vaccination. In this regard, the composition of the antigenic repertoire expressed by the constituent whole cell vaccine becomes very important, while PAMPs can provide molecular components required for the activation of Ag-presenting cells (APCs). Furthermore, activation of APCs is a key requirement for the generation of an optimal adaptive immune response against cognate Ags contained within such vaccines.

Importantly, the in vitro culture medium utilized to generate whole cell-based vaccines can significantly impact the expression of antigenic determinants and PAMPs on the infectious agent. Several microbes have been shown to differentially express Ags depending on the growth medium utilized, including Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica (1), Listeria monocytogenes (2), Helicobacter pylori (3), and Mycobacterium bovis (BCG) (4, 5). Direct evidence supporting an impact of growth medium on the efficacy of whole cell-based vaccines comes from a study involving BCG where its differential cultivation in Sauton versus Middlebrook medium significantly altered its protective efficacy (6). However, the mechanism responsible for this apparent difference has not been well established.

In regard to Francisella tularensis (Ft), it has been found that its antigenic repertoire can change depending on the growth medium employed for in vitro cultivation. Specifically, we previously demonstrated that the protein profile expressed by Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI)-grown Ft closely resembles that of in vivo circulating Ft, while Ft grown in Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) exhibits a distinct protein profile (7, 8). Interestingly, other investigations have revealed that BHI- and MHB-grown Ft also differ in their ability to interact with complement and antibodies (9). In addition, BHI-grown Ft exhibits a diminished ability to elicit pro-inflammatory cytokines by various APCs compared with inactivated Ft (iFt)-MHB (10, 11). These features of BHI- versus MHB-grown Ft provide unique and necessary tools to investigate the dichotomy between the antigenic repertoire versus APC-activating components of whole cell-based Ft vaccines.

In this study, we examined the differences in protective efficacy of iFt vaccine prepared by growth in MHB or BHI and further evaluated if the difference in protective efficacy observed reflects changes in not only the immune response but also APC function. While we initially hypothesized that BHI-grown iFt, which more closely mimics the antigenic repertoire of in vivo macrophage-grown Ft, would provide the superior vaccine immunogen, we found that iFt-MHB generates superior protection compared to iFt-BHI. Other indicators of protection, such as bacterial burden, tissue damage, and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, also correlated with the improved protective efficacy of iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI. Furthermore, we found that iFt-MHB exhibited significantly higher binding to APCs, higher induction of dendritic cell (DC) maturation, and increased Ag presentation to Ft-specific T cells. Overall, this investigation suggests that APC activation components are important for protective efficacy of inactivated whole cell-based vaccines. Moreover, growth conditions employed to prepare these vaccines can significantly influence their immunological and protective efficacy.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Six- to 8-week-old male and female C57Bl/6 mice were obtained from Taconic laboratories (Hudson, NY, USA). Mice were housed in the animal resource facility at Albany Medical Center. Food and water were provided ad libitum during the entirety of experiments. Animal studies were reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Albany Medical Center according to NIH guidelines.

Preparation of iFt

Francisella tularensis LVS was grown in MHB (Becton, Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) or BHI (Becton, Dickinson) medium at 37°C to a density of ~0.5–1 × 109 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml. To inactivate Ft LVS, 1 × 1010 CFU/ml of live bacteria were incubated in 1 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at room temperature with gentle shaking. Subsequently, fixed bacteria (iFt) were washed with sterile PBS three times. Inactivation was verified by culturing a 100 µl of sample (1 × 109 iFt organisms) on chocolate agar plates (Becton, Dickinson) for 7 days. Protein contents were quantified using a bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma-Aldrich) as described (12). The iFt preparations were resuspended in PBS and stored in 1 ml aliquots at −20°C until use. Ft LVS for challenge was grown similarly and stored in liquid nitrogen until use.

Immunization and Challenge

Groups of six to eight mice with equal numbers of males and females were immunized on day 0 and 21 via the intranasal (i.n.) route. Each mouse was anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 20% ketamine plus 5% xylazine and subsequently administered 20 µl of PBS (vehicle), iFt-MHB, or iFt-BHI at a concentration of 37.5 ng, 75 ng, 150 ng, or 300 ng/20 μl. Immunized mice were then challenged on day 35 i.n. with 2× LD50 of Ft in 40 µl of PBS (single nostril) and subsequently monitored for survival for 21 days.

Quantification of Bacterial Burden

Following immunization and challenge, mice were euthanized at various time intervals, and lung and spleen were collected aseptically in PBS-containing protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and subjected to mechanical homogenization using Mini Bead Beater-8 (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA) using 1-mm zirconia/silica beads. Tissue homogenates were then diluted 10-fold in sterile saline, and 10 µl of each dilution was spotted onto chocolate agar plates in duplicate and incubated at 37°C for 48 to 72 h. The number of colonies on the plates were counted and expressed as CFU per milliliter for the respective tissue. Tissue homogenates were then centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min, and the clarified homogenates were stored at −20°C for subsequent cytokine analysis.

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay

Serum LDH levels were quantified following the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, mice were immunized and challenged as described for quantification of bacterial burden. Sera were collected on days 1, 3, 5, and 7 postinfection. Prechallenge sera were collected 11 days after booster immunization. Serum samples were diluted 1:100 with LDH assay buffer. Fifty microliters of diluted serum samples, standard, and blanks was added to separate wells in a 96-well microtiter plate. Fifty microliters of LDH substrate was subsequently added to each well. LDH converts NAD to NADH, which can be read calorimetrically at 450 nm. The amount of NADH generated between Tinitial (absorbance at 450 nm immediately after the LDH substrate) and Tfinal (absorbance at 450 nm immediately after the LDH substrate) by the LDH activity is first calculated (B). The LDH activity of the sample is determined by the formula LDH activity = (B × sample dilution factor)/(reaction time × V), where V is the sample volume added to well. LDH activity is reported as milliunit per milliliter.

Antibody (Ab) Titer Determination

Anti-Ft-Ab production in response to immunization with iFt-MHB versus iFt- BHI was measured by ELISA. Briefly, ELISA plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) were coated with 50 µl of Ft LVS (5 × 107 CFU/ml) in carbonate buffer [4.3 g/l sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5.3 g/l sodium carbonate (Sigma-Aldrich) at pH 9.4] for 16 h at 4°C. The plates were then washed with washing buffer [PBS (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich)] and blocked for 2 h with 200 µl of PBS containing 5% BSA. Serial threefold dilutions of sera (starting with 1/10) were added to the plates (100 µl/well) and incubated for 2 h at 4°C. After three washes with washing buffer, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse Ab specific for IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Plates were then washed three times with washing buffer, and then 100 µl of BCIP/NBT alkaline phosphatase substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. Plates were subsequently incubated for 2 h, and absorbance at 405 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western Blot Analysis

Samples derived from 10 µg (~1 × 108 cells) of Ft were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and boiled for 10 min prior to resolution through 4–12% gradient SDS-PAGE precast gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The running buffer was NuPAGE MES SDS buffer (Invitrogen). Gels were run at 90–160 V. Resolved gels were stained with either Coomassie blue (Bio-Rad) or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Coomassie-stained gels were scanned into Adobe Photoshop. Membranes were then blocked for 30 min with PBS, 0.05% Tween 20, 5% non-fat dry milk. Primary Abs were applied for overnight incubation at dilutions ranging from 1:500 to 1:60,000 in PBS-Tween. Following five washes with PBS-Tween, the membranes were incubated for 1 h with agitation with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). Following an additional five washes with PBS-Tween, the membranes were incubated for 1 h with agitation with streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Southern Biotech). Development of the chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal West Pico, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) was visualized using an Alpha Innotech imaging system in movie mode. Densitometric analysis of developed blots was performed as previously described (7, 9).

Ag-Presenting Cells

Dendritic cells were generated from bone marrow cells using mouse recombinant FLT-3 (rFLT-3) (R& D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) following a previously described method (13). Briefly, bone marrow cells were obtained from 6- to 8-week-old female C57Bl/6 mice and were incubated for 6 days in bone marrow-derived DC (BMDC) generation medium [Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium] supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 ng/ml rFLT-3, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Cellgro, Tewksbury, MA, USA), 2 mM l-glutamine (Cellgro), 1× non-essential amino acids (Cellgro), 0.05 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad), and 1× penicillin streptomycin (Cellgro). Fifty percent of the medium was replaced with fresh BMDC generation medium on day 3 during 6 days of incubation. Peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) were isolated from naïve mice. PECs were cultured with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, and non-adherent cells were removed by aspiration of medium after 24 h. Adherent cells, which comprise >90% macrophages, were used as APCs.

iFt Binding Assay

Binding of iFt was visualized by flow cytometry using GFP-expressing iFt, as previously described (13). GFP-expressing Ft LVS organisms were provided by Dr. Mats Forsman (Swedish Defense Research Agency, Stockholm) (14). Briefly, 1 × 106 BMDCs were incubated with 5, 10, 15, or 20 µg of GFP-expressing iFt-BHI or iFt-MHB in PBS. After 2 h incubation at 4°C, BMDCs were washed twice with PBS and stained with rat anti-mouse CD11c-Alexa 700 Ab and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry (LSRII, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The percent of GFP-positive CD11c DCs (indicative of iFt bound to DCs) were analyzed in respective samples.

In Vitro Analysis of Costimulatory Molecule Expression and Cytokine Secretion

Expression of costimulatory molecules on BMDCs was analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described (13). Briefly, 2 × 105 BMDCs were incubated for 24 h with PBS or 10 µg of iFt- MHB or iFt- BHI in an equivalent volume of PBS. Cells were then harvested and stained with Abs to the following surface markers: rat anti-mouse CD40-PE, rat anti-mouse CD80-APC, and rat anti-mouse CD86-Alexa 700. Cells were subsequently analyzed via flow cytometry.

Cytokine secretion by BMDCs was assayed following previously described methods (13). Briefly, 2 × 105 BMDCs were incubated with PBS or with 10 µg iFt- MHB or iFt-BHI for 24 h at 37°C. Culture supernatants were then collected and analyzed for cytokines using the Bio-Plex assay system as described below.

Cytokine Analysis

Cytokines were measured using Bio-Plex assay kits (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 µl of a 1× mixture of magnetic beads coupled with capture Abs for capturing desired cytokines were added to separate wells of flat bottom 96-well microtiter plate. Beads were washed (2×) with Bio-Plex wash buffer. Unless stated otherwise, all incubations were done at room temperature with plates sealed with a plastic sealer and covered with aluminum foil with gentle shaking. All washing was done with Bio-Plex washing buffer. Fifty microliters of diluted standards, blank, or samples was added to individual wells. Plates were incubated for 30 min and washed 3× with Bio-Plex washing buffer. Then 25 µl of 1× mixture of biotinylated detection Abs were added to each well and incubated for 30 min. Plates were washed again, and 50 µl of phycoerythrin-coated streptavidin was added to each well and incubated for 10 min. Plates were then rewashed, and 125 µl of assay buffer was added to each well. Plates were read via Luminex reader (Bio-Rad), and the quantity of each cytokine was deduced using a standard curve included in the assay.

Ag Presentation Assays

Antigen presentation assays were done as previously described (13). Briefly, 2 × 105 BMDCs or PECs were incubated overnight at 37°C with PBS or 5 µg of iFt-MHB or iFt-BHI. A total of 1 × 105 Ft-specific T cells (FT25 6D10 hybridoma cells) (13) in 100 µl medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS) were then added to each well. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 24 h in CO2 incubator, and supernatants were collected. Supernatants were then assayed for interleukin (IL)-5 (secreted by these cells in response to Ag) using the Bio-Plex assay as described earlier.

Statistics

The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used for survival curves. One-way analysis of variance or the unpaired Student’s t-test was used for the remaining figures. Data analysis was performed using Graph-Pad Prizm 5 (Graph-Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

iFt Exhibits Protein Profiles Similar to Its Live Counterpart

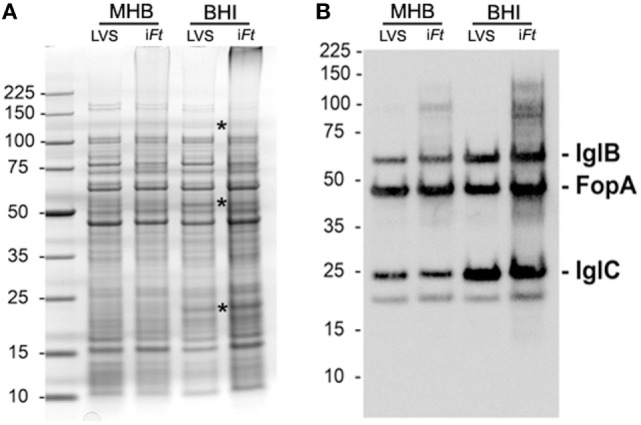

Before using iFt as immunogen, we first used SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis to examine the impact of our fixation procedure on the protein composition of Ft LVS. The overall protein profile of live and fixed Ft LVS was largely unchanged, although the fixed samples did show some expected evidence of cross-linked Ags (Figure 1A). Consistent with previous reports (7, 9), the BHI-derived samples contained elevated levels of ~23 and ~55 kDa proteins [Figure 1A (asterisks)], which were apparent in both the live and fixed bacteria. Western blot analysis indicated that the live and fixed BHI-derived samples contained levels of IglB and IglC that were elevated relative to their MHB-grown counterparts (Figure 1B). Densitometric analysis revealed that these increases were on the order of threefold to fivefold (Table S1 in Supplementary Material), as reported previously (7, 9). As our fixed iFt preparations appeared to be faithful representations of their live counterparts, we next examined the vaccine efficacy of these immunogens.

Figure 1.

Fixed Francisella tularensis (Ft) LVS used herein for immunization studies retain the protein composition of their unfixed counter parts. Ten micrograms of live and fixed Ft LVS previously grown in Mueller Hinton Broth and Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stained with Coomassie blue (A) or transferred for western blot analysis (B). Asterisks in A mark bands, which are visibly more abundant in the western blot of BHI-grown Ft (B). The membrane was probed with a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies specific for IglB, IglC, and a FopA-specific polyclonal mouse serum. IglB and IglC have previously been shown to be more abundant in BHI-grown Ft (7, 9). FopA is used here as a loading control. The ~18-kDa band visible under IglC is an unidentified, endogenously biotinylated Ft protein (likely AccB) detected by the streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase conjugate used during development of the western blots.

iFt-MHB Generates Superior Protection against Ft LVS-Induced Mortality versus iFt-BHI

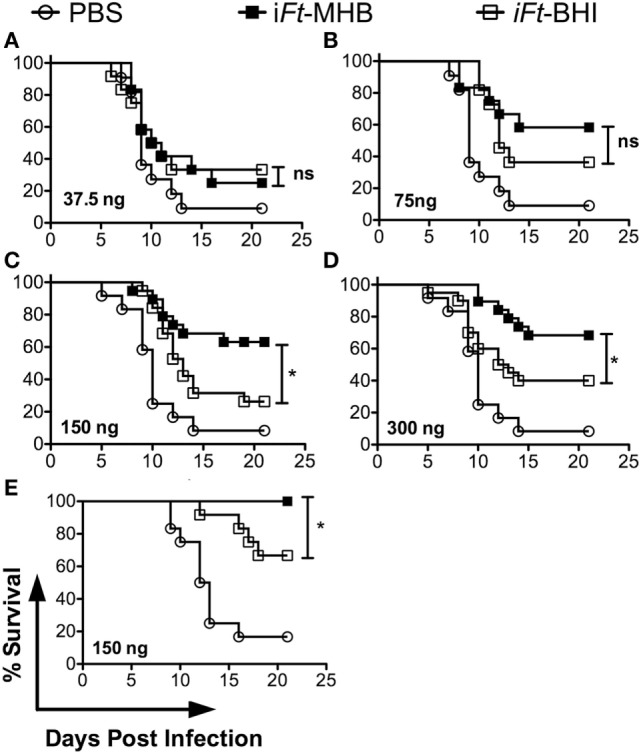

First, we evaluated whether the differential expression of antigenic repertoire and PAMPs affected by cultivation in MHB versus BHI has any impact on the protective efficacy of iFt. We used iFt generated in MHB or BHI to immunize mice. Following a lethal challenge with Ft LVS, we observed that iFt- MHB-immunized mice were better protected than iFt-BHI-immunized mice (Figure 2). Of the four doses used, the 150- and 300-ng doses exhibited statistically significant differences in the protection afforded by iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI (Figures 2C,D). Importantly, in Figures 2A–D mice were challenged with MHB grown Ft LVS. Thus, to evaluate any potential bias of growth medium used to culture the challenge organism (Ft LVS) on the outcome of survival, we similarly immunized mice with PBS or 150 ng of iFt-MHB or iFt-BHI, but challenged with BHI-grown Ft LVS Once again, we observed that iFt-MHB provided better protection compared to iFt-BHI (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) provides superior protection compared to iFt-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) against lethal Ft LVS challenge. Mice were immunized twice on days 0 and 21 with phosphate-buffered saline or iFt-MHB or iFt-BHI at a dose of 37.5 ng (A), 75 ng (B), 150 ng (C,E), or 300 ng (D). (A–D) Mice were infected 2 weeks after booster immunization with 2× LD50 of Ft LVS grown in MHB. (E) Mice were infected with 2× LD50 of Ft LVS grown in BHI. This figure represents Kaplan–Meier survival curves of three independent experiments with a total of 20 mice per group (A–D) or 1 experiment with 12 mice per group (E). *p < 0.05.

iFt-MHB-Immunized Mice Are Better Protected against Bacterial Replication and Tissue Damage following Ft LVS Infection, as Compared to That of iFt-BHI

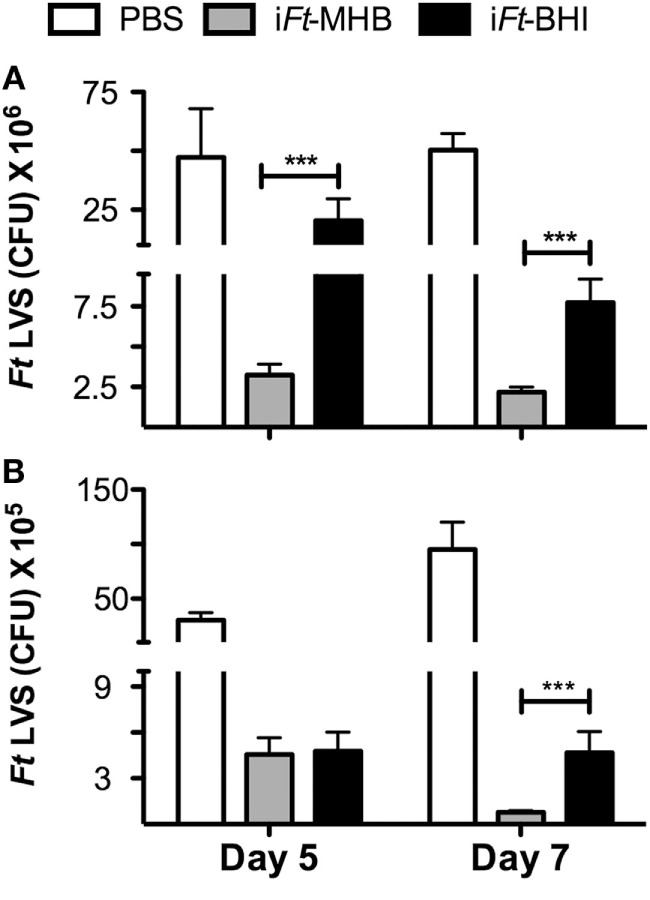

Following the above observation of differential protection afforded by iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI, we investigated the ability of the two iFt immunogens to protect against bacterial replication and tissue damage exerted by Ft LVS infection. Following immunization and Ft LVS challenge, we found significantly lower bacterial burdens in the lungs (Days 5 and 7) (Figure 3A) and spleen (Day 7) (Figure 3B) of mice immunized with iFt-MHB as compared to that of iFt-BHI.

Figure 3.

Inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) better reduces bacterial burden following Ft LVS infection as compared to that of iFt-BHI: mice were immunized as in Figure 2 with phosphate-buffered saline (white bars), iFt-MHB (gray bars), or iFt-BHI (black bars) and challenged with Ft LVS grown in MHB. Subsequently, Ft LVS colony-forming units were enumerated in the lung (A) and spleen (B) homogenates at indicated days postinfection. Each bar represents the mean ± SE (error bar) of two independent experiments with a total of eight mice per group. ***p < 0.001.

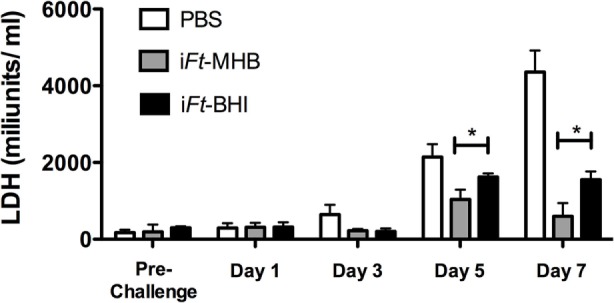

Francisella tularensis LVS infection inflicts systemic tissue damage in infected mice, and serum LDH levels are commonly used as a biomarker of tissue damage (15). Thus, we evaluated serum LDH levels at early and late stages of Ft LVS infection in mice immunized with iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI. At days 5 and 7 after Ft LVS infection, significantly lower levels of LDH activity were found in iFt-MHB-immunized mice versus that of iFt-BHI-immunized mice (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) induces superior resistance to Ft LVS-induced systemic tissue damage compared to that of iFt-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI): mice were immunized on days 0 and 21 with phosphate-buffered saline (white bars), iFt-MHB (gray bars), or iFt-BHI (black bars) and challenged with Ft LVS grown in MHB. Lactate dehydrogenase activity was quantified in serum drawn on indicated days postchallenge. Prechallenge sera were drawn 11 days after boost. Each bar represents mean ± SE (error bar) of two independent experiments with a total of eight mice per group. *p < 0.05.

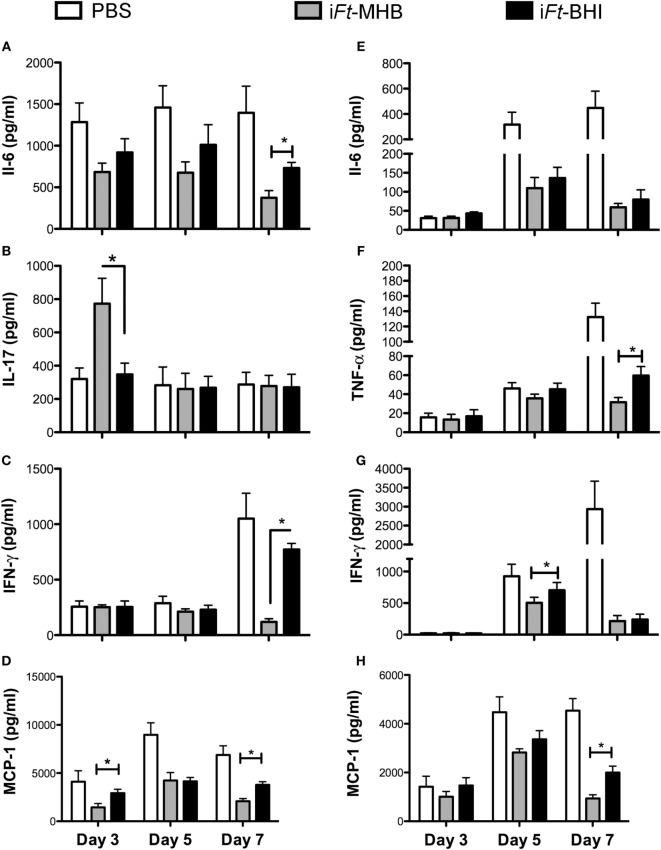

Differential Protection against Ft LVS-Induced Inflammation by iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI

Systemic inflammation and/or sepsis are hallmarks of the tularemia in advanced stages of infection. We previously observed that mice protected by immunization exhibit lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the lungs and spleens following Ft infection, compared to those of unprotected mice (16, 17). In this case, analogous to our previous studies, we observed that mice immunized with iFt-MHB, which are better protected, also exhibited lower levels of IL-6 (Figure 5A), interferon (IFN)-γ (Figure 5C), and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 (Figure 5D) in the lungs in the latter stage of disease (day 7 postinfection). MCP-1 levels were also lower at day 3 postinfection in the lungs of iFt-MHB immunized mice compared to that of iFt-BHI immunized mice. MCP-1 is a chemoattractant for inflammatory monocytes, which can induce to tissue damage. Therefore, regulation of MCP-1 levels is important for protection against systemic tissue damage and subsequent mortality inflicted by Ft LVS infection. Interestingly, higher levels of IL-17 were also found at day 3 postinfection in iFt-MHB immunized mice compared to that of iFt-BHI immunized (Figure 5B). IL-17 has been found to be protective against mucosal infections with bacteria including Ft (18, 19). Thus, higher IL-17 levels at early stages of infection correlate with superior protection afforded by iFt-MHB compared to iFt-BHI. Similarly, in the spleens, significantly lower levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (at day 7 postinfection) (Figure 5F), IFN-γ (day 5 postinfection) (Figure 5G), and MCP-1 (day 7 postinfection) (Figure 5H) were observed in mice immunized with iFt-MHB compared to that of iFt-BHI. However, level of IL6 (Figure 5E) in the spleens were comparable among mice immunized with iFt-MHB and iFt-BHI.

Figure 5.

Inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) is superior to iFt-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) in controlling Ft-induced inflammation in the lung. Mice were immunized with phosphate-buffered saline (white bars) or 150 ng of iFt-MHB (gary bars) or iFt-BHI (black bars) and challenged with Ft LVS Indicated cytokines were quantified in homogenates of lung (A–D) and spleen (E–H) at the indicated days postinfection. Values represent mean ± SE (error bar) of two independent experiments with a total of eight mice per group. *p < 0.05.

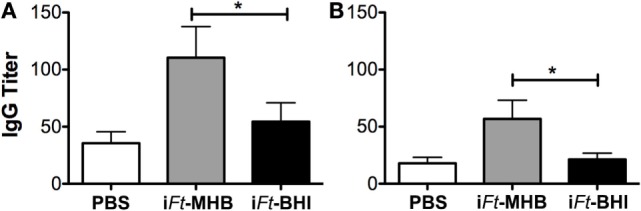

Increased Ab Responses Are Induced by iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI

Next we investigated whether iFt generated in MHB versus BHI medium also has a differential impact on the humoral immune response against Ft. We quantified Ft-specific serum-IgG by ELISA as a measure of humoral immune response to Ft. Live Ft LVS grown in BHI and MHB medium were coated onto ELISA plates and reacted with sera obtained from iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI-immunized mice. IgG induced by iFt-MHB compared to iFt-BHI reacted more strongly to Ft surface Ags expressed on both MHB- or BHI-grown Ft LVS, as evidenced by their relative titers (Figures 6A,B). This is consistent with superior protection afforded by iFt-MHB compared to that of iFt-BHI. The choice of Ags employed [Ft-MHB (Figure 6A) versus Ft-BHI (Figure 6B)] to detect Ab titers did not alter the relative pattern of Ab production observed in iFt-MHB or iFt-BHI-immunized mice.

Figure 6.

Increased Francisella tularensis (Ft)-specific antibody production is induced by inactivated Ft (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) versus iFt-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI). Mice were immunized twice at a 3-week interval with 20 µl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 150 ng of iFt-BHI or iFt-MHB via the intranasal route in 20 µl PBS. Sera obtained 2 weeks postboost were analyzed for Ft-MHB-specific (A) and Ft-BHI-specific (B) IgG. Values represent mean ± SE of two independent experiments (n = 16 mice per group). *p < 0.05.

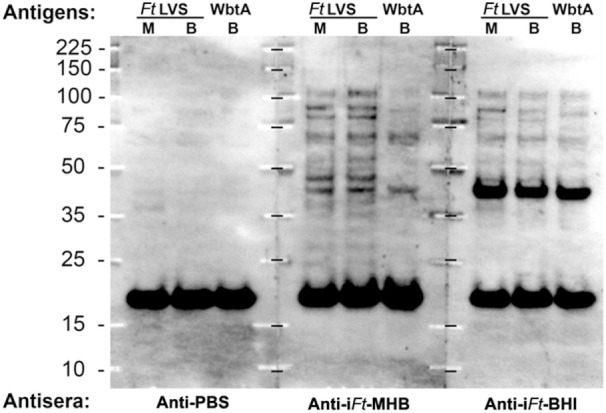

To further characterize these Ab responses, we also used the above sera to probe by western blot lysates of MHB- and BHI-grown Ft LVS along with a BHI-grown mutant Ft (WbtA), which is deficient for O-Ag. As shown in Figure 7, the anti-iFt-MHB sera recognized a more diverse array of Ags than did the anti-iFt-BHI sera. One of the Ags preferentially recognized by the anti-iFt-MHB sera appeared to have a ladder pattern typical of LPS, and consistent with this, this ladder pattern was markedly reduced/absent in the WbtA mutant Ft. In addition, the Ag specificity of the anti-iF-BHI sera appeared to be more focused on a ~43 kDa protein with reduced O-Ag-dependent reactivity. Collectively, the data in Figures 6 and 7, as well as in data not shown, indicate that immunization with iFt-MHB induces higher titers of anti-Ft Ab and that a larger proportion of this Ab is dependent on O-Ag for binding.

Figure 7.

Inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) elicits antibody (Ab) against broader range of antigens compared to iFt-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI). Ten micrograms of Ft LVS or WbtA LVS grown as indicated (M = MHB, B = BHI) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for western blot analysis. Membranes were incubated overnight with 1:500 dilutions of the indicated sera. Bound Abs were detected through sequential incubations with biotinylated goat anti-mouse and streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP). The prominent ~18 kDa band visible in all three blots is an unidentified, endogenously biotinylated Ft protein detected by the SA-HRP conjugate.

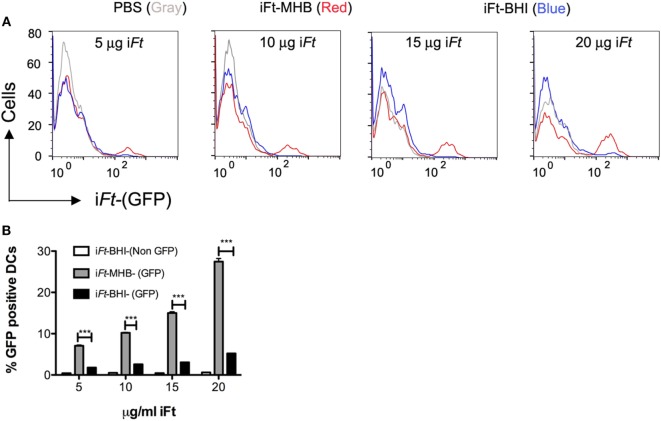

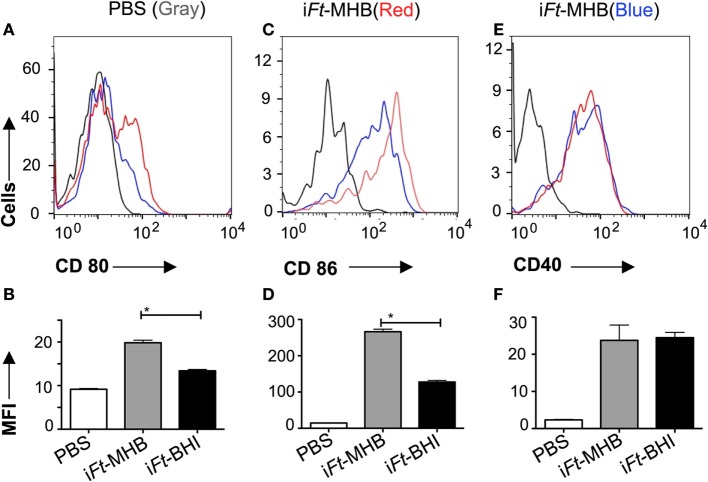

iFt-MHB and iFt-BHI Differentially Bind to BMDCs and Differentially Induce Expression of Costimulatory Molecules

Having observed differential protective efficacy between iFt generated in MHB versus BHI, we sought to further identify the immune mechanisms underlying the differences in protective efficacy of iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI. In our previous studies (7, 9) and Figure 1, we demonstrated that iFt-BHI exhibits an antigenic profile more similar to that of in vivo circulating Ft, as apposed to that of Ft-MHB. This is in contrast to our expectation that by virtue of exposing the host to iFt-BHI, which is more similar antigenically to in vivo replicating Ft, a better protective immune response would be achieved. This led us to further investigate the immune mechanisms responsible for this unexpected observation.

By using a GFP-expressing Ft LVS, we investigated whether iFt generated in MHB versus BHI have different abilities to bind to and activate APCs. In fact, we observed significantly higher binding of iFt-MHB-(GFP) to BMDCs compared to iFt-BHI-(GFP) (Figure 8). Increasing the concentration of the iFt-MHB-(GFP) successively increased the number of BMDCs harboring iFt-MHB. In contrast, iFt-BHI-(GFP) exhibited relatively poor binding to BMDCs at all concentrations used in this assay. Furthermore, costimulatory molecules are essential components for T cell activation. As demonstrated in Figure 9, iFt-MHB induced significantly higher expression of the costimulatory molecules CD80 (Figures 9A,B) and CD86 (Figures 9C,D), as compared to iFt-BHI, although CD40 (Figures 9E,F) expression was stimulated to a similar degree by both immunogens.

Figure 8.

Enhanced binding of inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) as compared to iFt-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI). Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were incubated with GFP-expressing iFt-BHI or iFt-MHB. Cells were washed and stained with CD11c antibody before analyzing with flow cytometry for GFP signal associated with BMDCs (A). (B) Percentage of GFP-positive (+) BMDCs as evaluated by flow cytometry. Values represent mean ± SE of two independent experiments. ***p < 0.001.

Figure 9.

Induction of higher expression of costimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells by inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth compared to iFt-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI). Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were incubated with iFt-BHI and iFt-MHB for 24 h. Expression of indicated cell surface markers were analyzed via flow cytometry (A,C,E). (B,D,F) The MFI of respective markers. Values represent mean ± SE of two independent experiments. *p < 0.001.

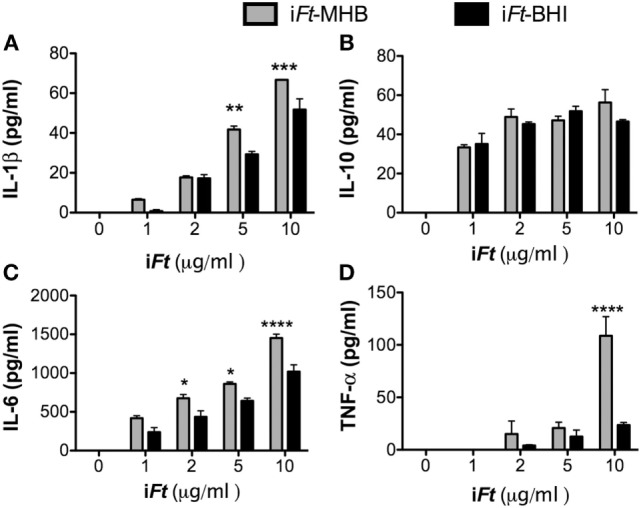

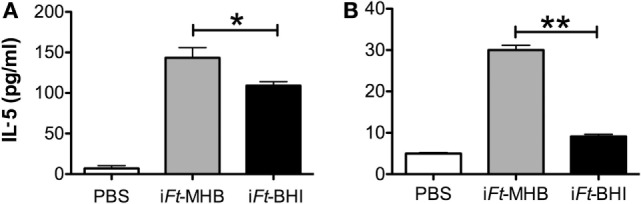

iFt-MHB Mediates Higher Pro-inflammatory Cytokine Production and Increased Ag Presentation to Ft-Specific T Cells

In addition to Ag binding and expression of costimulatory molecules on APCs, secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines is also critical for DC-mediated orchestration of the adaptive immune response. We observed that iFt-MHB induces higher levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines [IL-1β (Figure 10A), IL-6 (Figure 10C), and TNF-α (Figure 10D)], as compared to iFt-BHI, while both immunogens induced similar levels of IL-10. Finally, we investigated the presentation of iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI using an Ft-specific T cell hybridoma (FT25 6D10), which is specific to an epitope corresponding to Ft 50 s-ribosomal protein (20) and secretes IL-5 on engagement with cognate major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-peptide complex (13). Co-cultures of FT25 6D10 and APCs (PECs or BMDCs) exposed to iFt-MHB exhibited higher levels of IL-5 compared to that of iFt-BHI (Figure 11). Together, data presented in Figures 8–10 suggest that iFt-MHB harbors a superior ability to stimulate APC function as compared to iFt-BHI.

Figure 10.

Inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) elicits greater pro-inflammatory cytokine production compared to iFt-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI). Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were incubated with phosphate-buffered saline, iFt-BHI, or iFt-MHB for 24 h. Supernatants were analyzed for (A) IL1B, (B) IL10, (C) IL6, and (D) TNF-α. Values presented are mean ± SE of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 11.

Relative presentation of inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) and iFt-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) by antigen-presenting cells (APCs): APCs [peritoneal exudate cells (A) or bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (B)] were exposed to phosphate-buffered saline or 10 µg of iFt-MHB or iFt-BHI for 24 h. FT25 6D10 cells were then mixed with the APCs and incubated for 24 h. Supernatants were then collected analyzed for interleukin-5. Values represent mean ± SE of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

In the present investigation, we observed that iFt propagated in MHB versus BHI medium exhibits a differential ability to stimulate an immune response to and protection against Ft challenge. Specifically, iFt-MHB immunogen induced improved protection against lethal Ft LVS challenge as compared to iFt-BHI. Consistent with the superior protective activity of iFt-MHB immunogen, bacterial burden and tissue damage were also reduced. Furthermore, immunization with iFt-MHB leads to reduced inflammation in the lungs and spleens. Importantly, it has been demonstrated that mice protected against Ft LVS challenge via immunization exhibit lower pro-inflammatory cytokines in their lungs and spleen late in infection (16, 17), which we also observed in the case of iFt-MHB immunization. Notably, in contrast to the above, however, we observed elevated levels of IL-17 in lungs of mice immunized with iFt-MHB on day 3 postinfection with Ft LVS IL-17 has been implicated in protection against mucosal infections including Ft LVS (18, 19). Immunization with iFt-MHB also induced higher levels of Ft-specific IgG, which have been shown to play a role in protection against Ft LVS (21). Apart from quantitative differences in IgG titers, Abs produced in response to iFt-MHB and iFt-BHI also differed qualitatively. While the dominant reactivity of anti-iFt-BHI was to a 43 kDa protein, the anti-iFt-MHB response was more broadly distributed among a range of Ags including Ft LPS (O-Ag). Ft LPS has been found to be an important Ag for protection against Ft infection (22). Although, at present, we do not know the significance of the differences in the Ab responses elicited by iFt-MHB versus iFt-BHI, further studies in this regard may reveal their impact on protection.

In regard to the mechanisms(s) by which iFt-MHB is a better immunogen, APCs are the gateway to adaptive immune response. APCs present Ags to T cells in association with MHC, which provides the primary signal for T cell activation. Other signals required for T cell activation include costimulatory molecules, e.g., CD80 and CD86 (23–25). T cells that receive signals only via TCR by engagement with MHC-peptide complex, without receiving the second signal from costimulatory ligands, are destined to undergo anergy (26). Moreover, the local cytokine niche determines the type of T cell response generated. For example, IL-12 and IFN-γ favor a T helper 1 immune response, while IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β favor a regulatory T cell immune response (27, 28). Furthermore, APCs can be activated to express MHC II, costimulatory molecules, and pro-inflammatory cytokines by exposing them to various pathogen-associated molecular patterns (23). Therefore, it is important that APCs are exposed to vaccine Ags in the context of appropriate APC activation signals (29). In this investigation, iFts derived from growth in MHB medium exhibited a superior ability to activate APCs versus iFt-BHI. Specifically, MHB-derived iFt exhibited an increased ability to induce CD80 and CD86 on BMDCs. iFt-MHB also induced higher pro-inflammatory cytokine production in BMDCs. Moreover, we also observed higher levels of Ag presentation/T cell activation induced by BMDCs exposed to iFt-MHB versus to iFt-BHI. Notably, iFt-MHB also exhibited comparatively greater binding to BMDCs than iFt-BHI. The increased binding may explain the higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine stimulation and Ag presentation by iFt-MHB (Figure 7). Observations from other investigators are consistent with our observations (10, 11) that iFt-MHB can induce higher pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to iFt-BHI. Thus, collectively, it is clear that iFt-MHB exhibits a superior ability to impact the nature and magnitude of adaptive immune response, thereby enhancing its protective efficacy. The apparent differences in APC engagement between iFt-MHB and iFt-BHI may be a reflection of their structural differences. In this regard, we have demonstrated that BHI-grown Ft LVS expresses additional layers of capsular polysaccharides, which have been implicated in hindering Fts’ ability to bind with complement and Abs (9). Capsular polysaccharides have also been implicated in masking TLR2 and Tul4 ligands on the surface of Ft (9). Furthermore, Singh et al demonstrated that Ft grown in MHB exhibited increased engagement of cytosolic DNA sensors, possibly due to structural defects resulting in an increased release of DNA into cytosol after uptake by APCs, thereby inducing AIM 2-dependent cytokine production (11). The LPS of Ft LVS has a peculiar structure that minimizes its interaction with TLR4. Also, recently it has been shown that genetic engineering of microbes that express E. coli LPS significantly enhances their TLR4 engagement with bone marrow-derived macrophage (30). Thus, in future, one potential means to improve Fts’ ability to engage and activate APCs may be to genetically engineer Ft to express modified TLR agonists such as E. coli LPS.

It is also important to note that environmental conditions such as temperature, metal ions present, pH, and other media ingredients used for in vitro growth can significantly influence antigenic expression by bacterial pathogens (8). Various investigations have demonstrated the significance of growth conditions on bacterial recognition by Abs (1–3). In this investigation, we demonstrate that the two growth media employed for preparation of iFt LVS whole cell vaccines significantly altered the vaccine-induced immune response and protection against cognate pathogen. Recently, BCG vaccine exhibited differential protective efficacy based on the presence or absence of detergents in the growth medium. The latter was associated with differential expression of capsular polysaccharides, the presence of capsule specific Ab, splenic IL-17 and IFN-γ production, and multifunctional CD4+ T cell responses (31). We have also observed differential protective efficacy of BHI- and MHB-grown live Ft LVS vaccine, where BHI-grown Ft LVS exhibited better protection against lethal infection with Ft SchuS4 (32). This contrasting observation may be due to the distinct immunological requirements for protection against Ft LVS and Ft SchuS4 or live versus inactivated vaccine. Thus, we are further investigating this distinction in our laboratory. Nevertheless, these studies strongly emphasize the critical importance of growth conditions when developing whole cell vaccines.

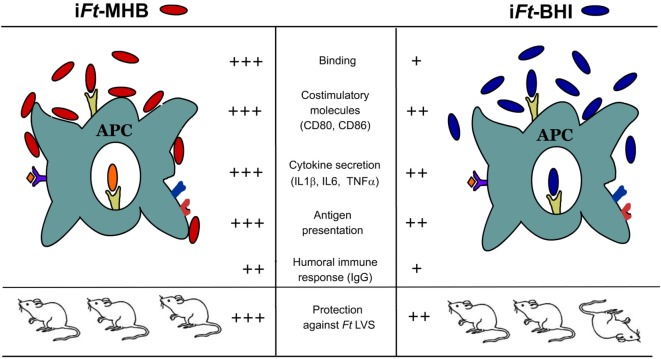

Conclusion

When we started this investigation, the goal was to improve the efficacy of Ft LVS-based whole cell vaccines. Our assumption was that by exposing the host to an antigenic repertoire more similar to that of the infecting agent in vivo (iFt-BHI), a superior protective immune response would be generated as compared to iFt-MHB (7). However, as depicted in Figure 12, we observed that iFt-MHB elicited a superior ability to stimulate the immune response and protection, as compared to iFt-BHI. In conclusion, our observations indicate that to endow hosts with protective immune response, vaccine formulations should simultaneously deliver a variety of protective Ags as well as APC activation components. This investigation also emphasizes that in vitro growth conditions, which influence Ag expression as well as APC activation capacity, are critical variables that must be considered when developing whole cell-based vaccines.

Figure 12.

A model comparing observations when utilizing inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) versus iFt-Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) as immunogen. iFt-MHB in comparison to iFt-BHI engages and activates antigen (Ag)-presenting cells (APCs) including significantly higher binding, expression of costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86) and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [interleukin (IL)-1b, IL-6, and TNF]. iFt-MHB Ags are also presented to Ft-specific T cells more efficiently compared to iFt-BHI. Collectively, superior activation of APCs by iFt-MHB results in higher IgG response and protection against lethal Ft challenge.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Albany Medical Center, Albany, NY, USA. The protocol was approved by the IACUC of Albany Medical Center, Albany, NY, USA.

Author Contributions

EG, KH, and SK conceptualized and designed the study. SK, RS, GP, BF, and SR performed the experiments and acquired and analyzed the data. SK drafted the manuscript. EG and KH critically revised the manuscript. All the authors approved the publication of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yili Lin and Li Barry, Manager, Immunology core facility, Department of Immunology and Microbial Diseases, Albany Medical College, for their assistance in acquiring flow cytometry data.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01AI100138—KH & EG; RO1AI123129-KROH; P01AI056320—EG and KH). The funders have no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00677/full#supplementary-material.

References

- 1.Hahm BK, Bhunia AK. Effect of environmental stresses on antibody-based detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis and Listeria monocytogenes. J Appl Microbiol (2006) 100(5):1017–27. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02814.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geng T, Hahm BK, Bhunia AK. Selective enrichment media affect the antibody-based detection of stress-exposed Listeria monocytogenes due to differential expression of antibody-reactive antigens identified by protein sequencing. J Food Prot (2006) 69(8):1879–86. 10.4315/0362-028X-69.8.1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh EJ, Moran AP. Influence of medium composition on the growth and antigen expression of Helicobacter pylori. J Appl Microbiol (1997) 83(1):67–75. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Florio W, Batoni G, Esin S, Bottai D, Maisetta G, Favilli F, et al. Influence of culture medium on the resistance and response of Mycobacterium bovis BCG to reactive nitrogen intermediates. Microbes Infect (2006) 8(2):434–41. 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz RH. T cell anergy. Annu Rev Immunol (2003) 21:305–34. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venkataswamy MM, Goldberg MF, Baena A, Chan J, Jacobs WR, Jr, Porcelli SA. In vitro culture medium influences the vaccine efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Vaccine (2012) 30(6):1038–49. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazlett KR, Caldon SD, McArthur DG, Cirillo KA, Kirimanjeswara GS, Magguilli ML, et al. Adaptation of Francisella tularensis to the mammalian environment is governed by cues which can be mimicked in vitro. Infect Immun (2008) 76(10):4479–88. 10.1128/IAI.00610-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazlett KR, Cirillo KA. Environmental adaptation of Francisella tularensis. Microbes Infect (2009) 11(10–11):828–34. 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarrella TM, Singh A, Bitsaktsis C, Rahman T, Sahay B, Feustel PJ, et al. Host-adaptation of Francisella tularensis alters the bacterium’s surface-carbohydrates to hinder effectors of innate and adaptive immunity. PLoS One (2011) 6(7):e22335. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loegering DJ, Drake JR, Banas JA, McNealy TL, Mc Arthur DG, Webster LM, et al. Francisella tularensis LVS grown in macrophages has reduced ability to stimulate the secretion of inflammatory cytokines by macrophages in vitro. Microb Pathog (2006) 41(6):218–25. 10.1016/j.micpath.2006.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh A, Rahman T, Malik M, Hickey AJ, Leifer CA, Hazlett KR, et al. Discordant results obtained with Francisella tularensis during in vitro and in vivo immunological studies are attributable to compromised bacterial structural integrity. PLoS One (2013) 8(3):e58513. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, et al. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem (1985) 150(1):76–85. 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iglesias BV, Bitsaktsis C, Pham G, Drake JR, Hazlett KR, Porter K, et al. Multiple mechanisms mediate enhanced immunity generated by mAb-inactivated F. tularensis immunogen. Immunol Cell Biol (2013) 91(2):139–48. 10.1038/icb.2012.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thelaus J, Andersson A, Mathisen P, Forslund AL, Noppa L, Forsman M. Influence of nutrient status and grazing pressure on the fate of Francisella tularensis in lake water. FEMS Microbiol Ecol (2009) 67(1):69–80. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00612.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guzman-de la Garza FJ, Ibarra-Hernandez JM, Cordero-Perez P, Villegas-Quintero P, Villarreal-Ovalle CI, Torres-Gonzalez L, et al. Temporal relationship of serum markers and tissue damage during acute intestinal ischemia/reperfusion. Clinics (Sao Paulo) (2013) 68(7):1034–8. 10.6061/clinics/2013(07)23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rawool DB, Bitsaktsis C, Li Y, Gosselin DR, Lin Y, Kurkure NV, et al. Utilization of Fc receptors as a mucosal vaccine strategy against an intracellular bacterium, Francisella tularensis. J Immunol (2008) 180(8):5548–57. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bitsaktsis C, Rawool DB, Li Y, Kurkure NV, Iglesias B, Gosselin EJ. Differential requirements for protection against mucosal challenge with Francisella tularensis in the presence versus absence of cholera toxin B and inactivated F. tularensis. J Immunol (2009) 182(8):4899–909. 10.4049/jimmunol.0803242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skyberg JA, Rollins MF, Samuel JW, Sutherland MD, Belisle JT, Pascual DW. Interleukin-17 protects against the Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain but not against a virulent F. tularensis type A strain. Infect Immun (2013) 81(9):3099–105. 10.1128/IAI.00203-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Y, Ritchea S, Logar A, Slight S, Messmer M, Rangel-Moreno J, et al. Interleukin-17 is required for T helper 1 cell immunity and host resistance to the intracellular pathogen Francisella tularensis. Immunity (2009) 31(5):799–810. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valentino MD, Abdul-Alim CS, Maben ZJ, Skrombolas D, Hensley LL, Kawula TH, et al. A broadly applicable approach to T cell epitope identification: application to improving tumor associated epitopes and identifying epitopes in complex pathogens. J Immunol Methods (2011) 373(1–2):111–26. 10.1016/j.jim.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavine CL, Clinton SR, Angelova-Fischer I, Marion TN, Bina XR, Bina JE, et al. Immunization with heat-killed Francisella tularensis LVS elicits protective antibody-mediated immunity. Eur J Immunol (2007) 37(11):3007–20. 10.1002/eji.200737620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, Valentine JL, Huang CJ, Endicott CE, Moeller TD, Rasmussen JA, et al. Outer membrane vesicles displaying engineered glycotopes elicit protective antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2016) 113(26):E3609–18. 10.1073/pnas.1518311113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blander JM. Phagocytosis and antigen presentation: a partnership initiated by Toll-like receptors. Ann Rheum Dis (2008) 67(Suppl 3):iii44–9. 10.1136/ard.2008.097964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol (2004) 5(10):987–95. 10.1038/ni1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature (1998) 392(6673):245–52. 10.1038/32588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuklina EM. Molecular mechanisms of T-cell anergy. Biochemistry (Mosc) (2013) 78(2):144–56. 10.1134/S000629791302003X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell (2006) 124(4):783–801. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reis e Sousa C. Dendritic cells in a mature age. Nat Rev Immunol (2006) 6(6):476–83. 10.1038/nri1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amsen D, Blander JM, Lee GR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T, Flavell RA. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell (2004) 117(4):515–26. 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00451-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan Y, Zanoni I, Cullen TW, Goodman AL, Kagan JC. Mechanisms of toll-like receptor 4 endocytosis reveal a common immune-evasion strategy used by pathogenic and commensal bacteria. Immunity (2015) 43(5):909–22. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prados-Rosales R, Carreno LJ, Weinrick B, Batista-Gonzalez A, Glatman-Freedman A, Xu J, et al. The type of growth medium affects the presence of a mycobacterial capsule and is associated with differences in protective efficacy of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis (2016) 214(3):426–37. 10.1093/infdis/jiw153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sunagar R, Kumar S, Franz BJ, Gosselin EJ. Tularemia vaccine development: paralysis or progress? Vaccine (Auckl) (2016) 6:9–23. 10.2147/VDT.S85545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.