Abstract

Background

BTC are uncommon and associated with a dismal prognosis. Gemcitabine and platinum-combinations (GP) form the standard approach for treating advanced BTC. To characterize the spectrum of mutations and to identify potential biomarkers for GP response in BTC, we evaluated the genomic landscape and assessed whether mutations affecting DNA repair were associated with GP resistance.

Methods

Pretreatment FFPE samples from 183 BTC patients treated with GP were analyzed. Cox regression models were used to determine the association between mutations, progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

Results

Considering genes with an incidence >10%, no individual gene was independently predictive of GP response. In patients with unresectable BTC who received GP as first-line therapy, the joint status of CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A were associated with PFS (P=0.0004) and OS (P=<0.0001). Patients with mutations in CDKN2A and TP53 were identified as a poor prognostic cohort with a median PFS and OS of 2.63 and 5.22 months. Patients with mutant ARID1A regardless of single mutational status of TP53 or CDKN2A had similar outcomes. A patient who exhibited mutations in all three genes had a median PFS of 20.37 months and OS not reached.

Conclusions

In the largest exploratory analysis of this nature in BTC, the presence of three prevalent, mutually exclusive mutations represents distinct patient cohorts. These mutations are prognostic and may represent a predictive biomarker to GP response. Prospective studies validate these findings are needed, including the incorporation of therapies that exploit the genomic instability observed with these mutations in BTC.

Keywords: biliary tract cancer, gemcitabine platinum based therapy response, next generation sequencing, tumor somatic variants

Introduction

Biliary tract cancers (BTC) include intra- and extra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma, as well as gallbladder cancers.1 BTC are rare and typically chemoresistant with a universally poor prognosis.2 The mechanisms for cholangiocarcinogenesis are complex and involve multiple molecular downstream signaling pathways and cytokines that contribute to tumor growth and chemoresistance.3, 4

Most patients present with advanced disease at the time of diagnosis and the standard treatment for untreated advanced biliary tract cancer consists of a combination of gemcitabine and platinum-based therapy (GP).5 However, resistance to chemotherapy is heterogeneous and responses are of varying duration. Although the majority of patients (>80%) experience disease control with GP, a substantial number of patients, are primarily resistant to GP chemotherapy and progress rapidly.6, 7 Alternatively, patients may experience a prolonged, durable response that can last up to several years. In several pre-clinical studies, there is evidence that the efficacy of various chemotherapeutic agents, including cisplatin and gemcitabine, requires functional cell cycle regulator genes, including TP53 and CDKN2A (p16) for effective induction of apoptosis and that the loss of these genes enhances resistance to cytotoxic agents.8-11 Epigenetics may also play a role in treatment resistance. For example, loss of the chromatin remodeler ARID1A has been implicated in both cancer progression and chemoresistance.12

The increased availability of targeted next-generation sequencing panels (NGS) has facilitated in the understanding of the molecular alterations present in malignancies, including those present in BTC.13-16 Using targeted sequencing, we first characterized the spectrum of all somatic variants in BTC. Secondly, we examined specifically whether cell cycle or epigenetic modulators were predictive of response to GP-based combination therapy.

Materials and Methods

The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by The Ohio State University and MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board. Data from a total of 183 patients with BTC who underwent molecular testing, on pre-treatment tumor samples, between January 2012 and March 2015 at the Ohio State University Medical Center and MD Anderson Cancer Center was collected. All molecular testing was performed in Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratories and included a targeted NGS panel. We also reviewed the patients’ medical records to confirm diagnosis and pathology, determine treatment received, duration of platinum-based chemotherapy, and death of any cause.

Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing

Available pre-treatment formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue (FFPE) from biopsies of primary or metastatic tumor sites were sent for targeted NGS at Foundation Medicine (Cambridge, MA) from patients with BTC. Foundation Medicine simultaneously assesses the entire coding sequences of 236 cancer-related genes, 7 introns from 19 genes often rearranged or altered in cancer to an average depth of coverage of greater than 250 times.17-20 Foundation Medicine categorized genomic alterations were categorized as “actionable” if they were linked to an approved or available investigational therapy. However, several of these “actionable” mutations do not have active available therapies, including approved targeted agents or actively in investigation in clinical trials for these genomic alterations. Thus, we have termed mutations categorized as “actionable” as “confirmed mutations.” Mutations of unknown significance were not accounted for, as they were not assessed in early sequencing results from Foundation Medicine, which included a proportion of patients included in this study.

Statistical Methods

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to determine the association between patient characteristics, mutations with PFS and OS. Genes mutated in 10% or greater of these patients were included in the analysis. Significance was defined as P<0.05. Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction was used to estimate the false-discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p-values to control for multiple testing in genomic data.

Results

Patient characteristics and common NGS alterations

Pre-treatment samples from 183 patients with BTC were tested with NGS. Baseline patient and tumor characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients were found to have predominantly intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (77.6%), followed by extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (16.9%), gallbladder (4.9%) and ampullary cancer (0.5%).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| Variable | (N=183) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median | 63 |

| Range | 24-86 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 89 (48.6) |

| Male | 94 (51.4) |

| Extend of disease | |

| Localized | 41 (22.4) |

| Locally advanced | 59 (32.2) |

| Metastatic | 83 (45.4) |

| Primary tumor site | |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 142 (77.6) |

| Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 31 (16.9) |

| Ampulla | 1 (0.6) |

| Gallbladder | 9 (4.9) |

| Type of tumor | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 177 (96.7) |

| Carcinoma, type not specified | 3 (1.6) |

| Adenosquamous | 1 (0.6) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2 (1.1) |

| Previous Surgery | |

| No | 111 (60.7) |

| Yes | 72 (39.3) |

| Stage | |

| I-II | 46 (25.1) |

| III | 9 (4.9) |

| IV | 128 (70) |

| Race | |

| White | 139 (76) |

| Non-white | 1 (0.6) |

| African American | 12 (6.5) |

| Asian | 9 (4.9) |

| Other | 10 (5.5) |

| Hispanic | 12 (6.5) |

| Previous Radiation Therapy | |

| No | 138 (75.4) |

| Yes | 45 (24.6) |

| Targeted therapies | |

| No | 126 (68.9) |

| Yes | 57 (31.1) |

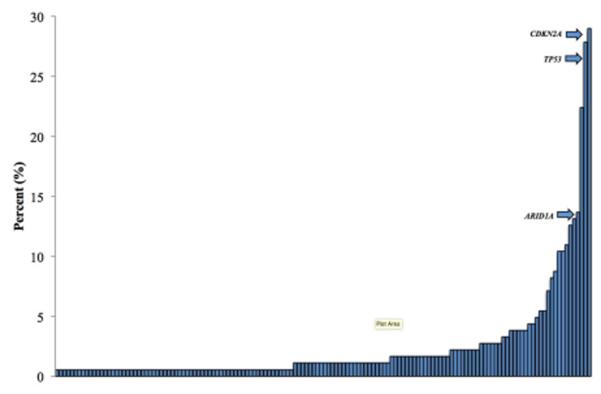

Of those patients, 181 (99%) had at least one confirmed molecular alteration, where the median number of targetable genomic alterations was 3 (range 0-21). While the incidence of most mutations was small, we observed a long-tail distribution in the identified mutations (Figure 1A). Loss of CDKN2A was the most commonly observed mutation (53 pts, 29%), followed by TP53 (27.9%), KRAS (22.4%), and ARID1A loss (13.7%;Table 2) (analysis). Nine mutations were prevalent in greater than 10% of the patients. While the median number of mutations for all patients was small, a trend (p value = NS) towards an increase in number of mutations was seen in patients with more advanced (stage III or IV, 137 patients) disease (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1. Tumor somatic variants identified in BTC.

Figure above shows the incidence of all identified cancer-related genes in the 183 tumor samples tested with next-generation sequencing. The arrows are indicating the incidence of CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A in relation to all identified tumor somatic variants.

Table 2.

Incidence of most frequent tumor somatic variants

| Mutation | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| MCL1 | 5.5 |

| PTEN | 5.5 |

| ATM | 7.1 |

| BRAF | 8.2 |

| BAP1 | 8.7 |

| PBRM1 | 10.4 |

| SMAD4 | 10.4 |

| PIK3CA | 10.9 |

| FGFR2 | 12.6 |

| IDH1 | 13.1 |

| ARID1A | 13.7 |

| KRAS | 22.4 |

| TP53 | 27.9 |

| CDKN2A | 29.0 |

Table 2 shows the incidence of the most common cancer-related genes (> 5%) in the 183 tumor samples tested with next-generation sequencing.

Univariate analysis of identified mutations

We next assessed the predictive and prognostic implication of single tumor somatic variants. We only considered mutations where the incidence was greater than 10%. Using this assumption, no individual gene was independently predictive for chemotherapeutic response. Mutations in TP53 (HR 2.63; q=0.0042) was associated with worse overall survival (OS) while patients who exhibited mutations in FGFR2 (HR 0.14; q=0.094) trended toward improved OS independent of stage at the time of diagnosis (Table 3). When adjusting for stage, TP53 (HR 3.15; q=0.025) remained significant associated with OS in patients with advanced, unresectable BTC(Table 4).

Table 3.

Tumor somatic variants and their association with overall survival in BTC

| Mutation | Frequency (%) | HR | Median OS (Mos.) | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARID1A(+) | 25(13.66%) | 0.937 | 39.59 | 0.9532 |

| ARID1A(−) | 158(86.34%) | . | 37.65 | . |

| CDKN2A (+) | 53(28.96%) | 1.117 | 49.15 | 0.9058 |

| CDKN2A (−) | 130(71.04%) | . | 39.59 | . |

| FGFR2(+) | 23(12.57%) | 0.141 | Not reached | 0.0067 |

| FGFR2(−) | 160(87.43%) | . | 34.76 | . |

| IDH1(+) | 24(13.11%) | 0.665 | 39.59 | 0.6162 |

| IDH1(−) | 159(86.89%) | . | 34.76 | . |

| KRAS(+) | 41(22.40%) | 1.673 | 19.65 | 0.1364 |

| KRAS(−) | 142(77.60%) | . | 45.96 | . |

| PBRM1(+) | 19(10.38%) | 1.003 | Not reached | 0.9935 |

| PBRM1(−) | 164(89.62%) | . | 39.59 | . |

| PIK3CA(+) | 20(10.93%) | 0.684 | 42.58 | 0.7401 |

| PIK3CA(−) | 163(89.07%) | . | 37.65 | . |

| SMAD4(+) | 19(10.38%) | 1.163 | 49.15 | 0.9058 |

| SMAD4(−) | 164(89.62%) | . | 39.59 | . |

| TP53(+) | 51(27.87%) | 2.625 | 19.29 | 0.0003 |

| TP53(−) | 132(72.13%) | . | 67.12 | . |

Genes with an incidence > 10% of all patients with were assessed for their association with overall survival. (+) indicates the presence of a mutation in the listed gene.

Table 4.

Most common tumor somatic variants and their association with patient outcomes in advanced, unresectable BTC

| Mutation | Frequency(%) | HR | Median OS (Mos.) | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARID1A(+) | 11(12.79%) | 1.557 | 11.42 | 0.3120 |

| ARID1A(−) | 75(87.21%) | . | 18.60 | . |

| BRAF(+) | 12(13.95%) | 0.576 | Not reached | 0.3120 |

| BRAF(−) | 74(86.05%) | . | 12.32 | . |

| CDKN2A_B(+) | 28(32.56%) | 0.602 | Not reached | 0.3120 |

| CDKN2A_B(−) | 58(67.44%) | . | 12.32 | . |

| FGFR2(+) | 11(12.79%) | 0.116 | 25.76 | 0.0520 |

| FGFR2(−) | 75(87.21%) | . | 12.09 | . |

| IDH1(+) | 10(11.63%) | 0.556 | Not reached | 0.3120 |

| IDH1(−) | 76(88.37%) | . | 16.82 | . |

| KRAS(+) | 21(24.42%) | 1.677 | 9.56 | 0.3120 |

| KRAS(−) | 65(75.58%) | . | 21.85 | . |

| PBRM1(+) | 10(11.63%) | 0.898 | 12.32 | 0.8201 |

| PBRM1(−) | 76(88.37%) | . | 16.82 | . |

| PIK3CA(+) | 13(15.12%) | 0.531 | 42.58 | 0.3120 |

| PIK3CA(−) | 73(84.88%) | . | 14.46 | . |

| SMAD4(+) | 9(10.47%) | 2.038 | 8.28 | 0.3120 |

| SMAD4(−) | 77(89.53%) | . | 18.60 | . |

| TP53(+) | 25(29.07%) | 3.154 | 8.44 | 0.0018 |

| TP53(−) | 61(70.93%) | . | 25.36 | . |

Genes with an incidence > 10% of all patients with stage III or IV BTC were assessed for their association with overall survival. (+) indicates the presence of a mutation in the listed gene.

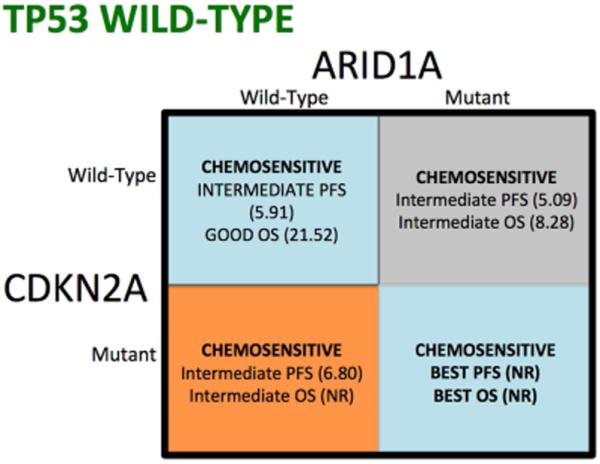

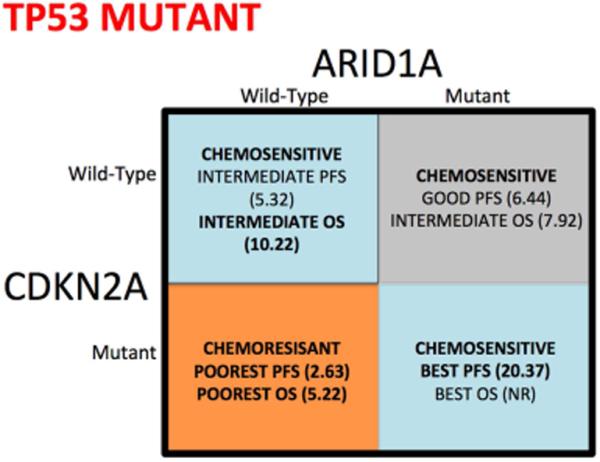

TP53 subset analysis identifies responder and non-responder groups

Given the importance of TP53 mutations in our univariate analysis and after adjusting for stage, we assessed whether patients with TP53 mutations constituted multiple groups, specifically in patients with advanced or metastatic BTC (stage III or IV) who received GP in the first-line setting. This constituted 86 patients. 98% of patients who received GP based therapy in the first-line setting received gemcitabine and cisplatin, while 2% had received oxaliplatin as the platinum agent for their treatment. We only considered mutations that were common in at least 10% (n=14) of the tumors in question, thus, no individual gene was independently predictive for GP response. When looking at the combination of multiple tumor somatic variants, we noted that loss of function mutations in CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A status were significantly associated with overall survival (OS) (P=<0.0001) and progression free survival (PFS) (P=0.0004) in those patients.

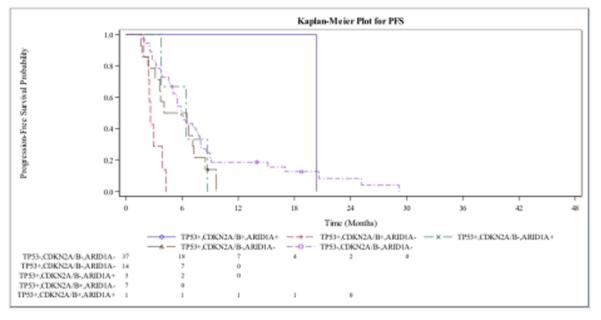

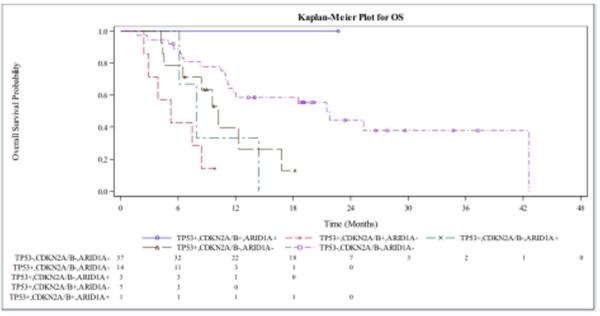

Patients wild-type for CDKN2A, ARID1A and TP53 had a median PFS of 5.91 months (95% CI, 4.99 to 7.92 months). Patients with a single tumor somatic variant in TP53, CDKN2A or ARID1A had median PFS of 5.32, 6.8 and 5.09 months, respectively. However, patients that exhibited loss of TP53 and CDKN2A in the absence of ARID1A mutations had the shortest median PFS with gemcitabine-platinum (GP) based therapy (2.63 months; 95% [CI], 1.93 to 3.88 months). Interestingly, in the presence of ARID1A mutations, PFS was improved in patients who exhibited either TP53 and/or CDKN2A mutations. Patients with mutations in TP53 and ARID1A had a PFS of 6.44 months, while the median PFS was not reached in patients with mutations in CDKN2A and ARID1A. In a single patient who exhibited mutations in TP53, CDKN2A and ARID1A, a median PFS of 20.37 months was observed (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Progression Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS).

Figure A shows the PFS in patients with advanced BTC who received gemcitabine-platinum-based chemotherapy with mutations in CDKN2A, ARID1A, TP53. Figure B shows OS for the same patient cohort. A single patient in the above figures had a mutation in all three genes and had the best response. Patients with mutations in CDKN2A and TP53 in the absence of ARID1A mutations were the worst performers.

A similar pattern was observed with overall survival (OS), where patients who exhibited mutations in TP53 and CDKN2A (in the absence of ARID1A), had a worse median OS (5.22 months; 95% CI, 2.43 to 8.41 months) while patients with mutations in CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A had a median OS that had not been reached (Figure 2B). Patients with a tumor somatic variant singly in TP53, or ARID1A had median OS of 10.22 and 8.28 months, respectively, while the median OS for patients who had a single mutation in CDKN2A was not reached (Figure 2B). The single patient who exhibited mutations in TP53, CDKN2A and ARID1A had a median OS that was not reached.

KRAS has no bearing on TP53, CDKN2A and ARID1A mutant tumors on patient outcomes

While the presence of KRAS mutations were non-significant in our univariate analysis, given the incidence and its prognostic relevance in other solid tumor malignancies, we assessed the incidence and interplay of KRAS with CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A, and its effect on patient outcomes (Supplemental Table 1). No patients were identified with mutations in all four genes (KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A and ARID1A). In patients with mutations in CDKN2A, no differences in PFS (P=0.4378) or OS (P=0.8928) were seen in the presence of KRAS mutations (Supplemental Figure 2A, 2B). The presence of KRAS mutational status on CDKN2A and TP53 mutant tumors on PFS and OS remained non-significant (Supplemental Figure 3A, 3B).

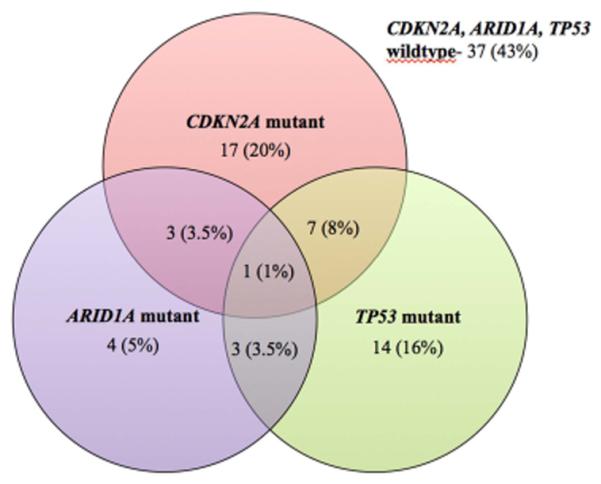

CDKN2A, ARID1A and TP53 are relatively mutually exclusive

Upon examining alterations in CDKN2A, ARID1A and TP53, our findings demonstrated that mutations in CDKN2A, ARID1A and TP53 tend to be mutually exclusive and are extremely rare to find together (Figure 3). Of the patients with multiple mutations in CDKN2A, TP53 or ARID1A, 13 (15%) exhibited 2 mutations in CDKN2A, TP53 or ARID1A while only 1 patient (1%) had a mutation in all 3 genes.

Figure 3. ARID1A, CDKN2A/B and TP53 mutational status in advanced BTC.

Figure 3 depicts the presence of ARID1A, CDKN2A or TP53 tumor somatic variants in patients with advanced BTC. Among the three cohorts, there is a poor overlap of the three mutated genes, with only 13 (15%) of patients with 2 mutations and only 1 (1%) patient exhibited mutations in ARID1A, CDKN2A and TP53.

To confirm and validate our findings, we examined four previously published external datasets. In BTC, complete exome sequencing data were aggregated from Li et al,21 Jiao et al,22 Ong et al 23 and Chan-On et al,24 representing 99 patients (36, 40, 8 and 15 patients, respectively), where 34 (34%) patients were found to have a mutation in ARID1A, CDKN2A or TP53 and 4 (4%) found to have two mutations. No patients in these 4 cohorts exhibited mutations in all 3 genes. (Fishers P< 0.001, Supplemental Figures 4A-D). Incidence of other confirmed mutations in tumors with mutations in CDKN2A, ARID1A or TP53 are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

Discussion

Biliary tract cancer (BTC) remains challenging with universally poor outcomes. Gemcitabine and platinum-based (GP) therapy remains the standard of care in BTC 5. However, response to GP is heterogeneous in patients with varied responses and duration. In our analysis, we attempted to identify what tumor somatic mutations may be specifically associated with cell cycle repair that could serve as predictive biomarkers of GP based therapy efficacy.

When evaluating the interplay of mutated genes in our study, our findings identified that mutations in CDKN2A, ARID1A and TP53 were significantly associated with outcome in patients with advanced BTC receiving GP as first line therapy. These same mutations have been previously described in the literature as mechanisms of cancer proliferation and chemoresistance in other malignancies.8-10, 25, 26

Loss of TP53, a tumor suppressor gene has been described to result in the accumulation of mutated proteins with potential gain-of-function activities, including hyperproliferation and chemotherapy resistance. Several studies in other tumor types have demonstrated the importance of TP53 and chemotherapy efficacy, where functional TP53 is necessary for effective apoptosis in response to cytotoxic agents. Conversely, the loss of TP53 function limits the efficacy and enhances resistance to conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy, and has been implicated in gemcitabine and platinum resistance in other malignancies.27-31

While the absence of TP53 has been identified as a mechanism for cholangiocarcinogenesis and chemoresistance, our findings suggest that TP53 requires an accompanying mutation to exert its full effect. In our set, mutations in TP53, in the presence of CDKN2A alterations, led to worse outcomes in BTC. These findings suggest that while the initial insult resulting from the loss of TP53 may be sufficient to drive tumor growth and proliferation, a second alteration affecting cell cycle function is required for GP resistance. CDKN2A, a tumor suppressor gene, functions as a regulator of the cell cycle by controlling the progression from G1 to S phase. Mutations or the loss in CDKN2A leads to the dysregulation of the cell cycle, causing rapid proliferation and chemotherapy resistance in many cancers. Thus, the combined loss of TP53 and CDKN2A function significantly inhibits proper cell cycle functioning and repair to result in inducing a hyperproliferative, anti-apoptotic state capable to overcome the DNA damaging effect of cytotoxic chemotherapy.

ARID1A encodes BAF250a, a member of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex and is believed to function as a tumor suppressor gene and is involved in integral regulatory cellular processes including DNA damage repair and cell cycle regulation.26, 32 The loss of ARID1A function impairs checkpoint activation and DNA double strand break (DSB) repair and serves as a mechanism for tumor formation and proliferation. Interestingly, in our study, alterations in ARID1A, in the presence of CKDN2A or TP53 mutations, led to improved outcomes in patients who received GP based therapy. The increased genomic instability as a result of multiple alterations of critical regulators of cell cycle function and DNA repair, may render the tumor unstable, as evidenced by few patients with this phenotype and may potentially sensitize cells to DNA damage inducing agents, including gemcitabine and platinum-based therapies.

Our findings also identified that alterations in CDKN2A, ARID1A and TP53 tend to be mutually exclusive, where multiple mutations in these three genes are uncommon (Figure 3). ARID1A, a binding partner of TP53,32 both play critical roles in DNA damage repair and the interplay between ARID1A and TP53 has been reported in other platinum-sensitive cancers where both mutations are unlikely to occur in the same patient.33, 34 CDKN2A and TP53 have been identified an important regulators of cell cycle function, where their absence can lead to a hyper proliferation and inhibit apoptosis. Importantly, the mutual exclusivity of ARID1A, CDKN2A and TP53 mutations and their differing in treatment response suggest that mutations in CDKN2A, ARID1A or TP53 represent distinct cohorts, where alterations ARID1A lead to a more chemo-sensitive phenotype in contrast to patients harboring CDKN2A and TP53 mutations. The incorporation of these genomic alterations into treatment strategies may unveil additional therapeutic options for BTC.

One potential strategy would be to exploit the DNA instability in tumors that exhibit ARID1A mutations.35 PARP inhibitors in ARID1A mutated tumors may simulate the tumoricidal activity observed in cells lacking BRCA1 or 2, two proteins involved in DNA double strand break repair.36-38 These findings have been demonstrated in pre-clinical studies, where treatment of ARID1A deficient tumor cells with various PARP inhibitors led to increased cell death and apoptosis.39 Several differing approaches that should be of consideration in ARID1A mutant BTC include examining the role of PARP inhibitors in combination with GP as first-line therapy. Another consideration should be investigating the role of PARP inhibitors in a maintenance strategy, similar to the POLO study, an ongoing, randomized phase III trial in BRCA mutated pancreatic cancer, where patients are randomized to olaparib or placebo, after demonstrating stable disease response on platinum-based chemotherapy (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02184185).

Alternatively, as ARID1A promotes the formation of chromatic remodeling complexes, ARID1A mutations may increase the sensitivity towards agents aimed at targeting chromatic remodeling, including histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, which are currently under investigation in various malignancies.40-42 Early pre-clinical studies have demonstrated anti-tumor activity in BTC cell lines with HDAC inhibitors confirming its potential therapeutic role in BTC.43-45

Lastly, mutations in ARID1A also co-exist with the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway, an integral signaling pathway in cholangiocarcinogenesis and treatment resistance in BTC.46-48 In patients with alterations to ARID1A, incorporating agents against the PI3k/Akt pathway may be of benefit, where preclinical studies have demonstrated increased sensitivity to these agents in ARID1A mutated cells.49, 50 Thus, several potential treatment strategies aimed at exploiting ARID1A alterations, utilizing novel therapies as single agents or in combination with GP may improve outcomes in this cohort of patients.

In contrast, the presence of both CDKN2A and TP53 mutations in BTC represent a cohort of patients who are likely to have limited benefit from GP-based chemotherapy. Strategies to consider for these patients include the identification of alternate mutations that may be targeted with novel therapeutic agents 13-16, 51 or strategies aimed at exploiting DNA instability in TP53 deficient tumors to induce an ARID1A-like mutation.35 Furthermore, agents aimed at inhibiting CDK4 and CDK6, the downstream effectors of CDKN2A (p16), are currently under investigation and approved in other malignancies, and represent an alternative approach to exploit the absence or alteration in CDKN2A.52-56

In conclusion, the interplay of mutations in CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A define distinct, mutually exclusive chemotherapy sensitivity cohorts to GP chemotherapy in BTC, with prognostic implications (Figure 4). This is the largest reported series incorporating patient outcomes and investigating the role of these mutations in chemotherapy resistance in BTC.14, 22, 57 We acknowledge that a major limitation for this study is its retrospective and exploratory nature. Additionally, given the relatively mutual exclusivity of CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A, patients with multiple mutations in represent a small proportion of patients, thus confirmatory and prospective studies are needed. However, previous studies have described the presence of the described mutations in CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A in BTC, and their underlying biological interplay in several other solid tumor malignancies.33, 34

Figure 4. Chemo efficacy in BTC based on CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A status.

Figure 4 is a visual depiction of the different cohorts based on CDKN2A, TP53, and ARID1A mutational status, to define response to chemotherapy in advanced biliary tract cancer. Red indicates poor prognosis cohort, whereas green represents the best performing cohorts. Figure A are patients wild-type for TP53, while figure B represents individuals with TP53 mutations.

Taking into consideration the rarity of BTC, future prospective studies conducted in a large, collaborative international effort, incorporating correlative genomic studies are needed to confirm the role of CDKN2A, TP53 and ARID1A and their relation to GP efficacy. Given the variety of CDKN2A, ARID1A and TP53 mutations, these studies will allow us to characterize and understand the functionality of different mutations and their role in DNA damage response, and to stratify patients for clinical studies of targeted therapies with novel agents. Validation of our findings will support the incorporation of novel therapies into developing strategies aimed at improving patient outcomes in BTC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnotes

Contributions:

Daniel H. Ahn assisted in data collection, data analysis, table preparation and manuscript preparation

Milind Javle assisted in study design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation

Chul W. Ahn assisted in data analysis, figure preparation and manuscript preparation

Apurva Jain assisted in data collection, manuscript preparation

Sameh Mikhail assisted in data collection, manuscript preparation

Anne M. Noonan assisted in data collection, manuscript preparation

Christina Wu assisted in data collection, manuscript preparation

Rachna T. Shroff assisted in data collection, manuscript preparation

James L. Chen assisted in study design, data analysis, manuscript preparation

Tanios Bekaii-Saab assisted in study design, data analysis, manuscript preparation

Disclosure: The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, Taylor-Robinson SD. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2005;366:1303–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goydos JS, Brumfield AM, Frezza E, Booth A, Lotze MT, Carty SE. Marked elevation of serum interleukin-6 in patients with cholangiocarcinoma: validation of utility as a clinical marker. Ann Surg. 1998;227:398–404. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199803000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park J, Tadlock L, Gores GJ, Patel T. Inhibition of interleukin 6-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase activation attenuates growth of a cholangiocarcinoma cell line. Hepatology. 1999;30:1128–1133. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hezel AF, Zhu AX. Systemic therapy for biliary tract cancers. Oncologist. 2008;13:415–423. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckel F, Schmid RM. Chemotherapy in advanced biliary tract carcinoma: a pooled analysis of clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:896–902. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowe SW, Ruley HE, Jacks T, Housman DE. p53-dependent apoptosis modulates the cytotoxicity of anticancer agents. Cell. 1993;74:957–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasey PA, Jones NA, Jenkins S, Dive C, Brown R. Cisplatin, camptothecin, and taxol sensitivities of cells with p53-associated multidrug resistance. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:1536–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vikhanskaya F, Clerico L, Valenti M, et al. Mechanism of resistance to cisplatin in a human ovarian-carcinoma cell line selected for resistance to doxorubicin: possible role of p53. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:155–159. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970703)72:1<155::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi YJ, Anders L. Signaling through cyclin D-dependent kinases. Oncogene. 2014;33:1890–1903. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu JN, Roberts CW. ARID1A mutations in cancer: another epigenetic tumor suppressor? Cancer Discov. 2013;3:35–43. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sia D, Losic B, Moeini A, et al. Massive parallel sequencing uncovers actionable FGFR2-PPHLN1 fusion and ARAF mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6087. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Wang K, Johnson A, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma reveals a long tail of therapeutic targets. J Clin Pathol. 2015 doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu AX, Borger DR, Kim Y, et al. Genomic profiling of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: refining prognosis and identifying therapeutic targets. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3827–3834. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3828-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross JS, Wang K, Gay L, et al. New routes to targeted therapy of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas revealed by next-generation sequencing. Oncologist. 2014;19:235–242. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gnirke A, Melnikov A, Maguire J, et al. Solution hybrid selection with ultra-long oligonucleotides for massively parallel targeted sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:182–189. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahl F, Stenberg J, Fredriksson S, et al. Multigene amplification and massively parallel sequencing for cancer mutation discovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9387–9392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702165104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porreca GJ, Zhang K, Li JB, et al. Multiplex amplification of large sets of human exons. Nat Methods. 2007;4:931–936. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foundation Medicine I Foundation One Technical Information and Test Overview. Available from URL: http://foundationone.com/ONE-I-001-20140804_(nobleed)TechnicalSpecs.pdf?__hstc=197910000.ca54bd200688390fb3cfffed497960ad.1401198872498.1424965584578.1424969165476.20&__hssc=197910000.1.1424969165476&__hsfp=3761051387 [accessed February 26, 2015, 2015]

- 21.Li M, Zhang Z, Li X, et al. Whole-exome and targeted gene sequencing of gallbladder carcinoma identifies recurrent mutations in the ErbB pathway. Nat Genet. 2014;46:872–876. doi: 10.1038/ng.3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiao Y, Pawlik TM, Anders RA, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent inactivating mutations in BAP1, ARID1A and PBRM1 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1470–1473. doi: 10.1038/ng.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ong CK, Subimerb C, Pairojkul C, et al. Exome sequencing of liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:690–693. doi: 10.1038/ng.2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan-On W, Nairismagi ML, Ong CK, et al. Exome sequencing identifies distinct mutational patterns in liver fluke-related and non-infection-related bile duct cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1474–1478. doi: 10.1038/ng.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robl B, Pauli C, Botter SM, Bode-Lesniewska B, Fuchs B. Prognostic value of tumor suppressors in osteosarcoma before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:379. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1397-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu RC, Wang TL, Shih Ie M. The emerging roles of ARID1A in tumor suppression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:655–664. doi: 10.4161/cbt.28411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reles A, Wen WH, Schmider A, et al. Correlation of p53 mutations with resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy and shortened survival in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2984–2997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiorini C, Cordani M, Padroni C, Blandino G, Di Agostino S, Donadelli M. Mutant p53 stimulates chemoresistance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells to gemcitabine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhayat SA, Mardin WA, Seggewiss J, et al. MicroRNA Profiling Implies New Markers of Gemcitabine Chemoresistance in Mutant p53 Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katagiri A, Nakayama K, Rahman MT, et al. Loss of ARID1A expression is related to shorter progression-free survival and chemoresistance in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:282–288. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowery WJ, Schildkraut JM, Akushevich L, et al. Loss of ARID1A-associated protein expression is a frequent event in clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancers. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:9–14. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318231f140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guan B, Wang TL, Shih Ie M. ARID1A, a factor that promotes formation of SWI/SNF-mediated chromatin remodeling, is a tumor suppressor in gynecologic cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6718–6727. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosse T, ter Haar NT, Seeber LM, et al. Loss of ARID1A expression and its relationship with PI3K-Akt pathway alterations, TP53 and microsatellite instability in endometrial cancer. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1525–1535. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang HN, Lin MC, Huang WC, Chiang YC, Kuo KT. Loss of ARID1A expression and its relationship with PI3K-Akt pathway alterations and ZNF217 amplification in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:983–990. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bitler BG, Fatkhutdinov N, Zhang R. Potential therapeutic targets in ARID1A-mutated cancers. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19:1419–1422. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2015.1062879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1382–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen J, Peng Y, Wei L, et al. ARID1A Deficiency Impairs the DNA Damage Checkpoint and Sensitizes Cells to PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:752–767. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma X, Ezzeldin HH, Diasio RB. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: current status and overview of recent clinical trials. Drugs. 2009;69:1911–1934. doi: 10.2165/11315680-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruscetti M, Dadashian EL, Guo W, et al. HDAC inhibition impedes epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity and suppresses metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2015 doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vleeshouwer-Neumann T, Phelps M, Bammler TK, MacDonald JW, Jenkins I, Chen EY. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Antagonize Distinct Pathways to Suppress Tumorigenesis of Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bluethner T, Niederhagen M, Caca K, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase for the treatment of biliary tract cancer: a new effective pharmacological approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4761–4770. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i35.4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu LN, Wang X, Zou SQ. Effect of histone deacetylase inhibitor on proliferation of biliary tract cancer cell lines. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2578–2581. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwahashi S, Ishibashi H, Utsunomiya T, et al. Effect of histone deacetylase inhibitor in combination with 5-fluorouracil on pancreas cancer and cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. J Med Invest. 2011;58:106–109. doi: 10.2152/jmi.58.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiegand KC, Hennessy BT, Leung S, et al. A functional proteogenomic analysis of endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas using reverse phase protein array and mutation analysis: protein expression is histotype-specific and loss of ARID1A/BAF250a is associated with AKT phosphorylation. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanno S, Yanagawa N, Habiro A, et al. Serine/threonine kinase AKT is frequently activated in human bile duct cancer and is associated with increased radioresistance. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3486–3490. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoon H, Min JK, Lee JW, Kim DG, Hong HJ. Acquisition of chemoresistance in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cells by activation of AKT and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;405:333–337. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bitler BG, Aird KM, Garipov A, et al. Synthetic lethality by targeting EZH2 methyltransferase activity in ARID1A-mutated cancers. Nat Med. 2015;21:231–238. doi: 10.1038/nm.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samartzis EP, Gutsche K, Dedes KJ, Fink D, Stucki M, Imesch P. Loss of ARID1A expression sensitizes cancer cells to PI3K- and AKT-inhibition. Oncotarget. 2014;5:5295–5303. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kelley RK, Bardeesy N. Biliary Tract Cancers: Finding Better Ways to Lump and Split. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2588–2590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sherr CJ, Beach D, Shapiro GI. Targeting CDK4 and CDK6: From Discovery to Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2015 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turner NC, Ro J, Andre F, et al. Palbociclib in Hormone-Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:209–219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:25–35. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stone A, Sutherland RL, Musgrove EA. Inhibitors of cell cycle kinases: recent advances and future prospects as cancer therapeutics. Crit Rev Oncog. 2012;17:175–198. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v17.i2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fry DW, Harvey PJ, Keller PR, et al. Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 by PD 0332991 and associated antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1427–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rashid A, Ueki T, Gao YT, et al. K-ras mutation, p53 overexpression, and microsatellite instability in biliary tract cancers: a population-based study in China. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3156–3163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.