Highlights

-

•

Primary hepatic lymphoma is difficult to diagnose preoperatively.

-

•

MTX use encouraged MTX-related ML.

-

•

In MTX-related MLs, withdrawing MTX had a therapeutic effect.

Keywords: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, Primary hepatic malignant lymphoma, Methotrexate

Abstract

Introduction

Recently, immunosuppressant-associated malignant lymphoma (ML) cases have been increasing along with the development of several effective immunosuppressant drugs for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Among methotrexate (MTX)-associated lymphoproliferative disorders, primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) in patients with RA following surgical resection has not been reported previously.

Presentation of case

A 65-year-old woman who is a hepatitis B virus carrier with a history of RA was admitted. MTX was introduced seven years prior as an RA treatment. Her laboratory data showed no elevation of several tumor markers, and liver function test results were normal. On contrasted computed tomography (CT) scanning, a slightly enhanced tumor was detected at the early phase, and tumor staining was sustained at the delayed phase. Further, subsegmentectomy of the S6 was performed. The pathological diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. However, positron emission tomography-CT and bone marrow aspiration sample showed no resident sign of ML.

Discussion

Diagnosis of PHL before surgery is difficult. If the mass lesion was solitary and had a certain degree of size, then resection could be performed for its treatment and diagnosis. The treatment for ML requires a diagnosis of the subtypes to select a therapeutic agent and determine the prognosis. Once a precise preoperative diagnosis was made, withdrawing MTX could be the first treatment in case of MTX-related ML.

Conclusion

Long-term usage of immunosuppressant drugs could cause proliferative ML. Considering the increasing occurrence of MTX-related ML, withdrawing MTX should be considered, especially in patients with long-term immunosuppressant usage for RA.

1. Introduction

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a rare disease among hepatic malignancies. The incidence of PHL was reported to be less than 1% among extranodular lymphoma cases [1]. Recently, along with the introduction of methotrexate (MTX) usage for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment, MTX-related malignant lymphoma cases have been increasing [2]. RA patients are susceptible to develop malignant lymphoma (ML). Moreover, these immunosuppressant drugs for RA override the occurrence of malignant diseases.

It is hypothesized that occult Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection relapse, which was activated by long-term usage of MTX, could cause PHL. Thus, long-term low dose usage of MTX is the risk factor for MTX-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (MTX-LPDs) [3]. Preoperative diagnosis of PHL was difficult due to the lack of characteristic radiological findings and its low incidence among liver malignancies. On computed tomography (CTs), low-density mass lesions are revealed, while on contrasted CT, tumors showed ischemic patterns. Further, T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance images (MRI) revealed low intense and high intense areas, respectively. However, these findings were not specific [4], [5]. Portal or hepatic veins extended through a hepatic lesion without evidence of appreciable mass effect, occlusion, or displacement of the vessels. These findings were also not specific, but can be used as a basis for suspicion [6].

Although increasing numbers of MTX-ML cases have been reported, the condition remains rare. This is the first case of solitary PHL without distant metastasis that developed during MTX treatment for RA. Our case demonstrated an MTX-associated PHL following curative resection supported with review of literatures.

2. Presentation of case

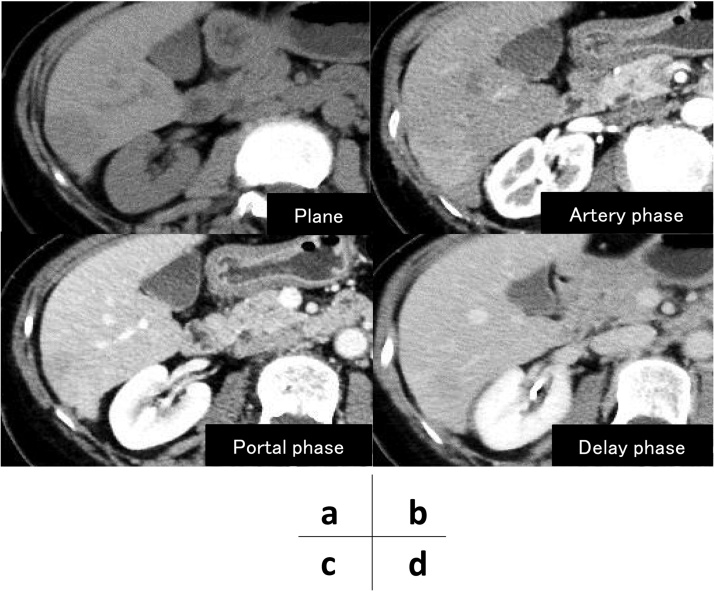

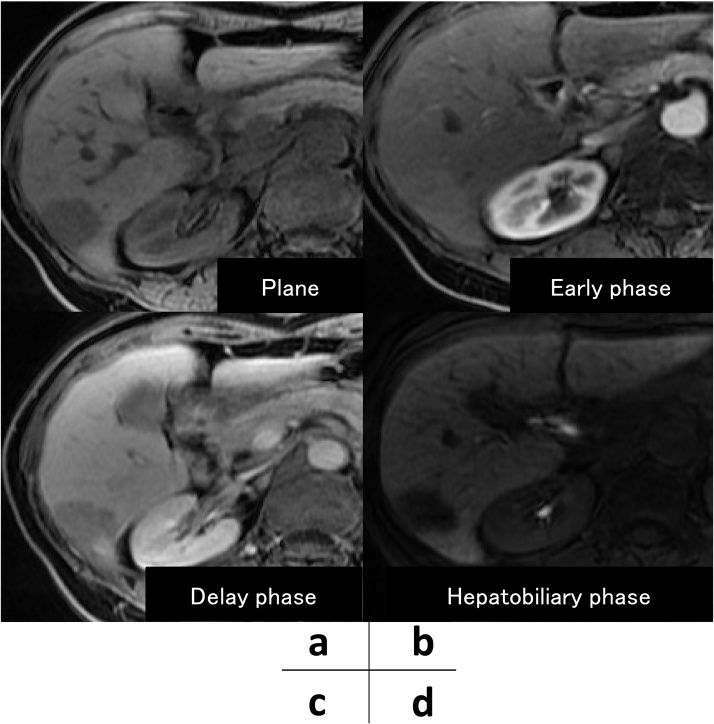

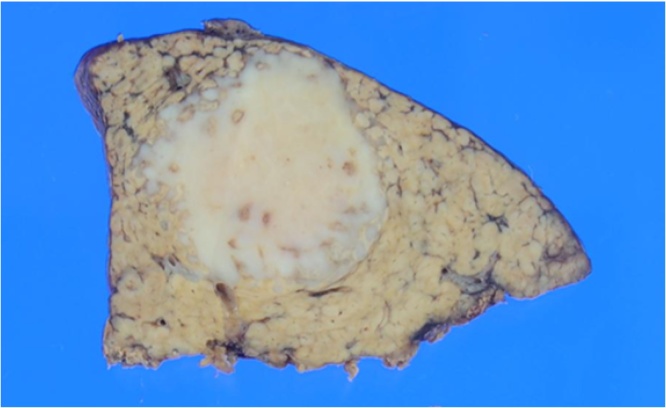

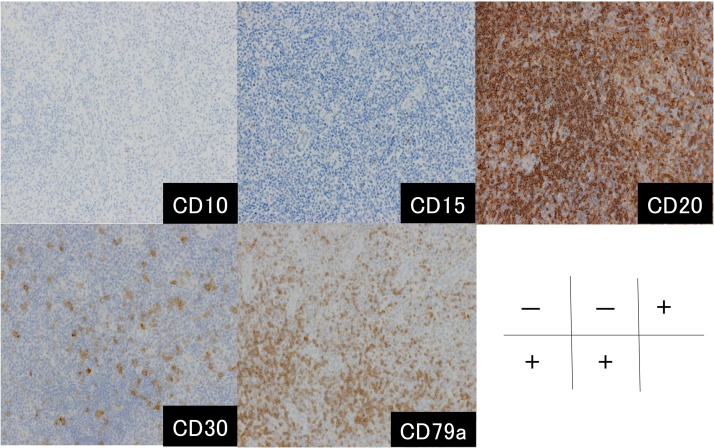

A 65-year-old woman was admitted for the treatment of her liver tumor in April 2015. Her height and weight were 146 cm and 48 kg, respectively. She is a hepatitis B virus carrier and has a history of RA. MTX was introduced seven years prior for RA treatment. Her laboratory data showed no elevation of several tumor markers. Both her physical examination and liver function test results were normal. On abdominal echo, a low echoic tumor was detected at segment 6 (S6), with a size of 16 × 29 mm. On contrasted CT, the tumor was slightly enhanced at the early phase, and tumor staining was sustained at the delayed phase (Fig. 1a–d). MRI showed that the tumor was weakly enhanced at the early phase, and revealed hypo intense areas at both late and hepatobiliary phases (Fig. 2a–d). The differential diagnoses include well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, metastatic liver tumor, and PHL. Subsegmentectomy of the S6 was performed with an operative time of 252 min and intraoperative bleeding amount of 240 mL. The specimen shows that the tumor was a whitish solid with an irregular margin (Fig. 3). The final pathological diagnosis was MTX-associated PHL. On immunohistochemical analysis, CD20, CD30, and CD79a were positive, but CD10 and CD15 were negative (Fig. 4). EBER (EBV-encoded small RNA) was also positive. These findings were consistent with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and other iatrogenic immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) according to the WHO 2008 classification of lymphoid tissue. However, positron emission tomography (PET)-CT and bone marrow aspiration sample did not indicate any sign of ML.

Fig. 1.

An abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed a solitary mass in the liver (a). The size was 16 × 29 mm. In the arterial phase (b), the tumor was slightly enhanced. In the portal and delayed phase (c, d), the tumor staining was sustained.

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a solitary mass in the liver. (a) The tumor was weakly enhanced in the early phase. (b) In the late and hepatobiliary phase (c, d), the tumor gradually revealed as a hypo intense area.

Fig. 3.

The specimen shows that the tumor was a whitish solid with an irregular margin.

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that the tumor was positive for CD20, CD30, and CD79a, but negative for CD10 and CD15.

The patient was discharged in our department without any complication, and was transferred to the hematology department of Kawasaki University. Additionally, bone marrow aspiration was performed, but residual tumor cells were not detected. She survived with no recurrence for one year even without any additional chemotherapy. MTX withdrawal was effective for the recurrence of ML afterwards.

3. Discussion

MTX-associated PHL following curative hepatectomy was demonstrated. To date, only a few reports of MTX associated with PHL were seen [1], [2], [7] (Table 1). In all cases, the pathological diagnosis was DLBCL. Diagnosis was performed with biopsy in all three cases, and the treatment was chemotherapy: either R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxyldaunorubicin, oncovin, prednisone) or R-THP-COP (rituximab, 4′-O-tetrahydropyranyl adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, oncovin, prednisone). In the present case, surgery was performed as both a therapeutic and diagnostic procedure, and follow-up was done after MTX discontinuation without chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Detailed clinicopathological findings and prognosis in four patients with MTX-associated PHL.

| Year | Author | Sex | Treatment | Diagnosis | Pathology | Number of tumors | Immunohistochemistry | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | K. Miyagawa | F | R-CHOP | US-guided aspiration biopsy |

DLBCL | Multiple | CD10+, CD79a+, CD20+ CD5-, EBER- |

Alive |

| 2014 | G. Tatsumi | F | R-THP-COP | US-guided fine-needle biopsy | DLBCL | Multiple | CD10-, CD20+, CD5- EBER+ |

Alive |

| 2015 | A. Kawahara | M | R-CHOP | Percutaneous tumor biopsy |

DLBCL | Multiple | CD10+, CD79a+, CD20+ bcl-2-, CD3-, EBER- |

Alive |

| 2016 | Our case | F | MTX withdrawal | Surgery | DLBCL | Single | CD10-, CD15-, CD20+ CD30+, CD79a+, EBER+ |

Alive |

Abbreviations: bcl, B cell lymphoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma; EBER, EBV-encoded small RNA; F, female; M, male; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, prednisone.

In 1991, the association between lymphoma and MTX therapy in patients with RA was first reported by Ellman et al. [8]. Patients with RA have various immunologic abnormalities, including T-cell dysfunction and B-cell activation associated with autoantigen stimulation [9]. The high inflammatory activity in these patients associated with RA, immunosuppressive agents including MTX used for treatment, or EBV infection/reactivation. In Japan, 95% of adults with latent infection of B-cells throughout their life were infected with EBV. In addition to EBV infection, immunologic abnormality and gene alteration in the infection cells encourage carcinogenic occurrences. In our case, EBV was positive and relapsed due to MTX usage, which was considered as a reason for the occurrence of PHL.

RA patients have a modestly increased risk of developing LPDs independent of immunosuppressive therapy for the disease. In RA treatment, the most popular immunosuppressive agent is MTX. MTX is usually used for several malignant diseases such as lymphoblastoma, trophoblastic disease, and leukemia. In one study on 29 RA patients with MTX-LPD, the median durations of RA and MTX treatment were reported to be 96 and 56 months, respectively, with a median cumulative dose of 864 mg [10]. In the present case, the duration of MTX treatment was 84 months, and the total dose of MTX was over 25,550 mg. This suggests that the immunosuppressive state induced by MTX may have played a major role in the development of PHL in the current patient.

Previous reports have indicated that EBV may be related to the development of MTX-LPD [11], [12]. Forty-six percent of MTX-LPD patients exhibited EBV-positive findings in the nuclei of the atypical cells of lymphoma [13]. Cell cycle dysregulation and latent EBV infection have been reported to be important factors for the development of LPD in autoimmune disease patients with an immunosuppressed condition due to treatment with MTX [14]. Further, EBV may be associated with spontaneous regression following the withdrawal of MTX in MTX-LPD patients. Salloum et al. reported that EBV was detected in eight out of ten patients who responded to the withdrawal of MTX, whereas only one of six EBV-negative patients responded to MTX withdrawal [15]. Therefore, the presence of EBV may be a predictive factor for the efficacy of MTX withdrawal.

Treatment option of PHL include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, or carrying out combinations of these modalities [16]. However, the optimal treatment is not established due to the heterogeneous occurrence patterns in patients. Chemotherapy with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, prednisone)-based regimens is generally the gold standard [16], [17]. The role of surgery is not fully clarified, but there are reports that liver resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation results in better prognosis [16], [18]. However, approximately 55% of MTX-LPD patients have been reported to improve following the withdrawal of MTX, without additional antitumor therapy [15].

Diagnosis has been difficult using the preoperative imaging tests, but malignant tumor was suspected from the size observed. We considered that curative resection was possible for a solitary lesion. Therefore, we performed surgery for its diagnosis and treatment. The pathological diagnosis was ML. Generally, it is better to take adjuvant chemotherapy. However, in the MTX-related ML, withdrawing MTX could be an effective therapy. In our case, we suspected MTX-related ML since the medical history of the patient reveals she was taking MTX. After the diagnosis of ML with surgery, we opted to withdraw MTX without adjuvant chemotherapy for the reason mentioned above.

Precise diagnosis played an important role in selecting the appropriate treatment. Therefore, it is important to consider MTX-related ML in patients with a history of MTX usage.

4. Conclusion

The frequency of MTX-associated PHL is rare, and the lack of characteristic findings makes it difficult to make a precise diagnosis. Long-term MTX use encouraged MTX-related ML, and withdrawing MTX alone could have a therapeutic effect. Therefore, it is important to monitor for PHL occurrence in patients treated with MTX on a long-term basis.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have any commercial or financial involvement in connection with this study that represents or appears to represent any conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Author contribution

All authors in this manuscript contributed to the interpretation of data, and drafting and writing of this manuscript. Daisuke Takei is first author of this paper. Tomoyuki Abe is corresponding author of this paper. Daisuke Takei, Tomoyuki Abe and Hironobu Amano conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Naomichi Hirano first diagnosed the hepatic tumor and introduced the patient to our department of surgery. Daisuke Takei, Tomoyuki Abe, Hironobu Amano, Masahiro Nakahara and Toshio Noriyuki were engaged in patient’s care in our hospital including surgery. Toshinori Kondo performed the postoperative treatment strategy. Tsuyoshi Kobayashi and Hideki Ohdan contributed to study concept, and review of the final manuscript and submission of the paper. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

Tomoyuki Abe.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- 1.Tatsumi G., Ukyo N., Hirata H., Tsudo M. Primary hepatic lymphoma in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate. Case Rep. Hematol. 2014;2014:460574. doi: 10.1155/2014/460574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyagawa K., Shibata M., Noguchi H., Hayashi T., Oe S., Hiura M. Methotrexate-related primary hepatic lymphoma in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern. Med. 2015;54:401–405. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng W.H., Cohen J.I., Fischer S., Li L., Sneller M., Goldbach-Mansky R. Reactivation of latent Epstein-Barr virus by methotrexate: a potential contributor to methotrexate-associated lymphomas. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1691–1702. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher M.M., McDermott S.R., Fenlon H.M., Conroy D., O’Keane J.C., Carney D.N. Imaging of primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Clin. Radiol. 2001;56:295–301. doi: 10.1053/crad.2000.0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee W.K., Lau E.W., Duddalwar V.A., Stanley A.J., Ho Y.Y. Abdominal manifestations of extranodal lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2008;191:198–206. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apicella P.L., Mirowitz S.A., Weinreb J.C. Extension of vessels through hepatic neoplasms: MR and CT findings. Radiology. 1994;191:135–136. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.1.8134559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawahara A., Tsukada J., Yamaguchi T., Katsuragi T., Higashi T. Reversible methotrexate-associated lymphoma of the liver in rheumatoid arthritis: a unique case of primary hepatic lymphoma. Biomark. Res. 2015;3:10. doi: 10.1186/s40364-015-0035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellman M.H., Hurwitz H., Thomas C., Kozloff M. Lymphoma developing in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis taking low dose weekly methotrexate. J. Rheumatol. 1991;18:1741–1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kudoh M., Harada H., Matsumoto K., Sato Y., Omura K., Ishii Y. Methotrexate-associated lymphoproliferative disorder arising in the retromolar triangle and lung of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2014;118:e105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niitsu N., Okamoto M., Nakamine H., Hirano M. Clinicopathologic correlations of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with methotrexate. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:1309–1313. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baecklund E., Askling J., Rosenquist R., Ekbom A., Klareskog L. Rheumatoid arthritis and malignant lymphomas. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2004;16:254–261. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200405000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamel O.W., van de Rijn M., Weiss L.M., Del Zoppo G.J., Hench P.K., Robbins B.A. Brief report: reversible lymphomas associated with Epstein-Barr virus occurring during methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis and dermatomyositis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;328:1317–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibilia J., Liote F., Mariette X. Lymphoproliferative disorders in rheumatoid arthritis patients on low-dose methotrexate. Rev. Rhum. Engl. Ed. 1998;65:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menke D.M., Griesser H., Moder K.G., Tefferi A., Luthra H.S., Cohen M.D. Lymphomas in patients with connective tissue disease. Comparison of p53 protein expression and latent EBV infection in patients immunosuppressed and not immunosuppressed with methotrexate. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000;113:212–218. doi: 10.1309/VF28-E64G-1DND-LF94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salloum E., Cooper D.L., Howe G., Lacy J., Tallini G., Crouch J. Spontaneous regression of lymphoproliferative disorders in patients treated with methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996;14:1943–1949. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noronha V., Shafi N.Q., Obando J.A., Kummar S. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005;53:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page R.D., Romaguera J.E., Osborne B., Medeiros L.J., Rodriguez J., North L. Primary hepatic lymphoma: favorable outcome after combination chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92:2023–2029. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2023::aid-cncr1540>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zentar A., Tarchouli M., Elkaoui H., Belhamidi M.S., Ratbi M.B., Bouchentouf S.M. Primary hepatic lymphoma. J. Gastrointest. Cancer. 2014;45:380–382. doi: 10.1007/s12029-013-9505-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]