Abstract

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) is characterized by delayed retinal vascular development, which promotes hypoxia-induced pathologic vessels. In severe cases FEVR may lead to retinal detachment and visual impairment. Genetic studies linked FEVR with mutations in Wnt signaling ligand or receptors, including low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) gene. Here, we investigated ocular pathologies in a Lrp5 knockout (Lrp5−/−) mouse model of FEVR and explored whether treatment with a pharmacologic Wnt activator lithium could bypass the genetic defects, thereby protecting against eye pathologies. Lrp5−/− mice displayed significantly delayed retinal vascular development, absence of deep layer retinal vessels, leading to increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and subsequent pathologic glomeruloid vessels, as well as decreased inner retinal visual function. Lithium treatment in Lrp5−/− mice significantly restored the delayed development of retinal vasculature and the intralaminar capillary networks, suppressed formation of pathologic glomeruloid structures, and promoted hyaloid vessel regression. Moreover, lithium treatment partially rescued inner-retinal visual function and increased retinal thickness. These protective effects of lithium were largely mediated through restoration of canonical Wnt signaling in Lrp5−/− retina. Lithium treatment also substantially increased vascular tubular formation in LRP5-deficient endothelial cells. These findings suggest that pharmacologic activation of Wnt signaling may help treat ocular pathologies in FEVR and potentially other defective Wnt signaling–related diseases.

Pathologic blood vessel development in the eye is a leading cause of blindness. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) is a genetic eye disease with varying penetrance characterized by poor formation of intraocular vasculature.1, 2 Although some FEVR patients are asymptomatic, children with severe FEVR present underdeveloped retinal vascularization, which can cause retinal hypoxia and ischemia, leading to pathologic proliferation of vessels that result in retinal detachment and visual impairment. Sometimes persistent hyaloid vessels are also observed, which normally regress as retinal vessels develop.3 Although the genetic causes of FEVR are still being intensively studied, to date the most common deficiencies are in genes encoding either receptors or ligand involved in the Wnt signaling pathway, including a Wnt receptor Frizzled4, the coreceptors low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) and tetraspanin 12 (TSPAN12),4 and Wnt signaling ligand Norrin.5, 6

Wnt signaling is an important regulatory pathway in embryonic development and diseases. Proper Wnt signaling activation is required for vascular development7 and plays a key role in numerous ocular diseases.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Canonical Wnt signaling starts with Wnt ligands (Wnts, small secreted proteins, or a structurally unrelated Norrin) binding to a cell surface receptor complex consisting of frizzled and Lrp5/6,13 which then suppresses a secondary signaling complex with glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), adenomatous polyposis coli, and axin, leading to stabilization of β-catenin.14 Stabilized β-catenin then translocates into the nucleus, where it associates with T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor to activate target gene transcription.8, 12, 15, 16 In FEVR, lack of any one of LRP5/Frizzled4/TSPAN12/Norrin causes deficient canonical Wnt signaling pathway at the ligand/receptor level, which allows the GSK3 complex to increase β-catenin degradation, resulting in eventual suppression of physiological vessel growth in the retina.2, 17 Both Sox17 and claudin5 were down-regulated in Wnt-deficient retinal vessels and were suggested to play a potential role in mediating vascular formation in FEVR retina,11, 18 although the exact underlying molecular mechanisms of Wnt signaling–mediated retinal vascular defects are not completely understood yet. To date, there is no effective treatment for FEVR. Clinical management mainly focuses on preventing and treating complications, such as retinal detachment and vitreous hemorrhage, by laser photocoagulation and vitrectomy,9, 19, 20 yet these approaches do not address the underlying causes of ocular pathology development. Therefore, it is highly desirable to fully characterize pathologic features in a mouse model of FEVR to facilitate targeted treatment approaches for FEVR by addressing the root cause of deficient Wnt signaling.

Knockout of Lrp5 (Lrp5−/−) in mice produces eye vascular pathologies that model FEVR in humans,17, 21 whereas heterozygous mice are largely phenotypically normal.17 Here, we fully characterized the development of ocular vascular pathologies, visual functional deficiency, in vivo eye measurements, and defective Wnt activation in Lrp5−/− eyes. Moreover, we hypothesized that one potential approach to treat FEVR is through bypassing the genetic defects at the receptor level and activating the Wnt signaling pathway downstream with the use of a Wnt activator lithium that inhibits GSK3β.22 Lithium is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved drug for treating bipolar disorder and other mental illness and has been used safely for more than half a century.23 We investigated whether lithium treatment may protect against retinal vascular pathologies and visual function in the Lrp5−/− mouse model of FEVR through restoring Wnt signaling.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Lrp5−/− mice (stock no. 005823; developed by Deltagen Inc., San Mateo, CA) and C57BL/6J mice (stock no. 000664) were both purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All animal experiments were approved by the Boston Children's Hospital Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Age-matched C57BL/6J mice were used as wild-type (WT) controls, as instructed by the vendor.

Drug Administration, Retina Dissection, Vessel Staining, and Flat Mounting

Littermate Lrp5−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected daily with 10 mg/kg body weight LiCl (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) from postnatal day 1 (P1) until the day of sacrifice. Littermate vehicle control Lrp5−/− mice were injected with an equal volume of PBS. Mice were anesthetized at P7 or P17 with 2 mg/g body weight ketamine and 4 mg/g body weight xylazine and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, and then the retinas were dissected. Subsequently, the retinas were incubated in PBS with 1% Triton X-100 for 2 hours at room temperature; this was followed by overnight staining with Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated Griffonia simplicifolia isolectin B4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). After washing, the retinas were whole-mounted onto a Superfrost/Plus microscope slide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) embedded in SlowFade Antifade reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and imaged with a Zeiss microscope to visualize the vasculature (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Vascularized retinal areas were quantified with Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) as described previously.24, 25, 26 The observers performing the analysis were masked with respect to the identity of the samples.

Hyaloid Vessel Dissection, Visualization, and Quantification

The hyaloid vessels from Lrp5−/− and WT eyes were dissected, visualized, and quantified, following an approach adapted from a previously published protocol.21 The enucleated and fixed (4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature) eyeballs were injected with 1.5% low melting point agarose in PBS. After 30 minutes on ice, the embedded hyaloid vessels were isolated from the eyecup and mounted with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), then imaged with a Zeiss microscope. The total number of blood vessels branching from the hyaloid canal was manually counted. The observer performing the analysis was masked with respect to the identity of the samples.

ERG

Retinal function was assessed by electroretinography (ERG) as previously described27 in P30 untreated WT mice and littermate Lrp5−/− mice treated with 10 mg/kg LiCl in PBS or PBS alone. In brief, pupils of dark-adapted, anesthetized (ketamine/xylazine) mice were dilated (Cyclomydril; Alcon, Fort Worth, TX), and the corneas were anesthetized (proparacaine). A Burian–Allen bipolar electrode designed for the mouse eye (Hansen Laboratories, Coralville, IA) was placed on the cornea, and the ground electrode was placed on a foot. The stimuli consisted of a series of green light-emitting diode flashes of doubling intensity from approximately 0.0064 to approximately 2.05 cd·s·m−2 and then white xenon-arc flashes from approximately 8.2 to approximately 1050 cd·s·m−2. The equivalent light for the green and white stimuli was determined from the shift of the stimulus/response curves. ERG stimuli were delivered using a Colordome Ganzfeld stimulator (Diagnosys LLC, Lowell, MA). The saturating amplitude and sensitivity of the rod photoresponse were estimated by fitting a model of the biochemical processes involved in the activation of phototransduction to the ERG a-waves.28, 29, 30 The saturating amplitude and sensitivity of b-waves of the dark-adapted postreceptor retina were derived from the Naka-Rushton equation.31 All ERG data were presented as the log change from normal (ΔLogNormal). By expressing the data in log values, changes in observations of fixed proportion become linear, consistent with a constant fraction for physiologically meaningful changes in variable values.32

OCT

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed to measure the retinal thickness in P30 nontreated WT and littermate Lrp5−/− mice treated with 10 mg/kg LiCl in PBS or PBS alone daily from birth to P30. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine. Pupils were dilated using Cyclomydril (Alcon). OCT images were obtained using a Micron IV retinal imaging OCT System (Phoenix Research Labs, Pleasanton, CA). Horizontal linear scans (1.5 μm width) were obtained while centered on the optic nerve head. Retinal thickness was measured using Insight software version 2.0.5618 (Phoenix Research Labs). Whole retinal thickness (nerve fiber layer to retinal pigment epithelium) and outer retinal thickness (outer plexiform layer to retinal pigment epithelium) were quantified to analyze the morphology.33

Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis of Gene Expression

Untreated WT mice and littermate Lrp5−/− mice treated daily with 10 mg/kg LiCl in PBS or PBS alone were sacrificed at P17, and total RNA was extracted from both retinas. Retinas were lyzed with a mortar and pestle and filtered through QiaShredder columns (Qiagen, Chatsworth, MD). RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions using an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). To generate cDNA, 1 μg of total RNA was treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to remove any contaminating genomic DNA, and reverse transcribed using random hexamers and SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). PCR primers targeting mouse Vegfa (forward: 5′-GGAGATCCTTCGAGGAGCACTT-3′, reverse: 5′-GGCGATTTAGCAGCAGATATAAGAA-3′), PCR primers targeting human LRP5 (forward: 5′-CTTCCACACTCGCTGTGAGG-3′, reverse: 5′-GGCAGGCGCATGTGTAGAA-3′), and a housekeeping control gene, 18S ribosomal RNA, for both human and mouse (forward: 5′-ACGGAAGGGCACCACCAGGA-3′, reverse: 5′-CACCACCACCCACGGAATCG-3′) were provided and validated by PrimerBank (Boston, MA). The relative mRNA levels were presented as the cDNA copy number of target genes normalized against 18S using the ΔΔ-CT method.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously.34 WT and Lrp5−/− mice were sacrificed at P17. Their retinas were collected, homogenized, and sonicated in RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich) and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentrations of the samples were normalized using Pierce BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples with 50 μg of total protein were loaded on an SDS-PAGE gel, separated by their molecular weights, and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies. Primary antibodies specific for phospho-GSK3β (Ser9), total-GSK3β, and non–phospho-β-catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Antibody for total–β-catenin (H-102) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Anti–β-actin antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich. Secondary incubations were performed with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). Chemiluminescent signals were generated with enhanced chemiluminescence plus substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and captured with Kodak film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Densitometry was performed using ImageJ software version 1.48v (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Vascular Endothelial Cell Culture and Tubular Formation

Human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs) were purchased from Cell Systems (Kirkland, WA) and cultured in Complete Medium supplemented with Cultureboost (Cell Systems). Tubular formation assay was performed using Matrigel (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Briefly, HRMECs (5 × 104 cells/well) were starved with serum-free basal medium overnight, transfected with negative control or LRP5 siRNA, and subsequently seeded onto Matrigel-coated plates in a serum-free medium containing 10 mmol/L LiCl or NaCl. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 9 hours. Vascular tubular formation was imaged and quantified by measuring branching points and vessel length per view field as described previously.35

MTT Assay and Cell Counting for Endothelial Cell Viability

HRMECs were treated with different concentrations of lithium chloride or sodium chloride (control) before being incubated with MTT reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for an additional 3 hours. Cell viability was measured as absorbance at 570 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For the effects of siRNA on cell viability, cells were treated with control siRNA or LRP5 siRNA, followed by MTT assay, or live cell staining by trypan blue (Bio-Rad), and counted by an automated cell counter (Bio-Rad).

Statistical Analysis

Results from animal studies were presented as means ± SEM; for nonanimal studies, data were presented as means ± SD. GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical comparisons. Comparisons between two groups were performed using t-test; comparisons among three or more groups were made using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test used for pairwise comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Development of Retinal Vasculature Is Delayed in Lrp5−/− Mice and Lithium Treatment Promotes Superficial Retinal Vascular Development

Human retinal vascular development starts at approximately 16 weeks of gestational age and is fully complete just before birth.36 Yet in mice, the retinal vasculature develops postnatally and hence provides an ideal model to study retinal angiogenesis. After birth, retinal vessels in mice grow radially from the optic disk and reach peripheral retina by P7 to P8.11, 17 Lrp5−/− mice displayed significantly less retinal vascular coverage and fewer branching points in the central superficial vascular plexus at P7 (Figure 1), compared with age-matched WT mice. Daily treatment with lithium (P1 to P7) accelerated retinal vascular growth, modestly improved superficial plexus vascular coverage (approximately 7.6% more than vehicle control), and substantially increased the number of branching points (approximately 42% more than vehicle control) at P7 compared with vehicle-treated Lrp5−/− littermates (Figure 1), indicating a proangiogenic role of lithium in the development of superficial vascular plexus in Lrp5−/− eyes.

Figure 1.

Lithium treatment promotes development of retinal vasculature in Lrp5−/− eyes. Littermate Lrp5−/− mice were i.p. injected with 10 mg/kg body weight LiCl or vehicle (Ctrl) daily. Retinal flat-mounts at P7 were analyzed. Age-matched WT mice were analyzed as controls. A: Representative flat-mounted retinas were stained with isolectin B4 (red) for vasculature. White dashed lines indicate retina edge. Yellow lines indicate the vascularized area edge. B: Representative images of selected areas of the superficial retinal vascular plexus. C: Quantification of the vascularized retinal area normalized to the whole retinal area. D: Quantification of branching points per field in the selected areas. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 8 to 12 per group (C and D). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Scale bars: 1000 μm (A); 100 μm (B). Ctrl, control; LiCl, lithium chloride; P7, postnatal day 7; WT, wild-type.

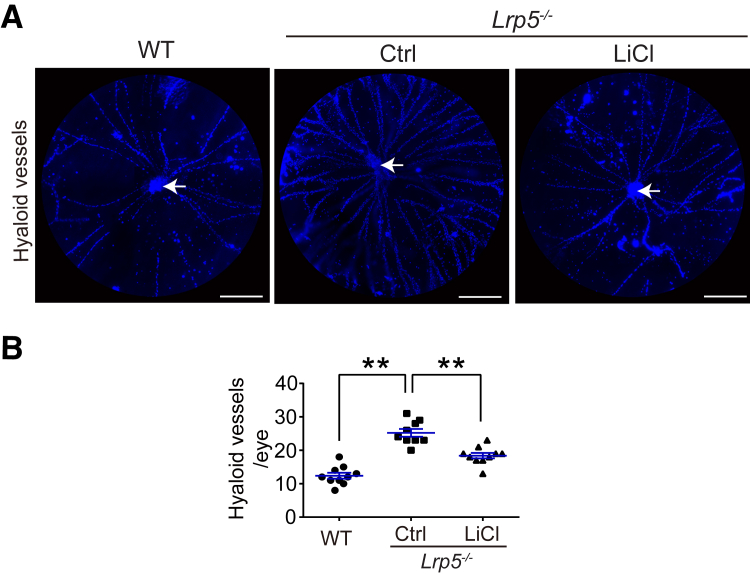

Hyaloid Vessels Are Persistent in Lrp5−/− Mice and Lithium Treatment Improves Hyaloid Regression

In addition to delayed retinal vascular development, FEVR is sometimes associated with persistent hyaloid vessels.37 Hyaloidal vasculature is critical during embryonic ocular development and normally regresses as retinal vascular development proceeds.38 At P8, Lrp5−/− mice had approximately double the number of hyaloid vessels branching from the hyaloid artery as those from the age-matched WT controls (Figure 2). Treatment with lithium (P1 to P7) significantly reduced the number of hyaloid vessels in P8 Lrp5−/− eyes by approximately 30% (Figure 2). This result suggests that lithium treatment was effective in promoting regression of persistent hyaloid in Lrp5−/− eyes.

Figure 2.

Lithium treatment promotes regression of hyaloid vessels in Lrp5−/− eyes. LiCl or vehicle Ctrl was injected i.p. into Lrp5−/− mice daily from P1 to P7. Mice were sacrificed at P8, and vitreous bodies were isolated then hyaloid vessels were stained with DAPI (blue). A: Representative images of flat-mounted hyaloid vessels (blue). Arrows (white) indicate the hyaloid artery. B: Quantification of the numbers of hyaloid vessels branching from the hyaloid artery. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 8 to 12 per group. ∗∗P < 0.01. Scale bar = 1000 μm (A). Ctrl, control; LiCl, lithium chloride; P1, postnatal day 1; WT, wild-type.

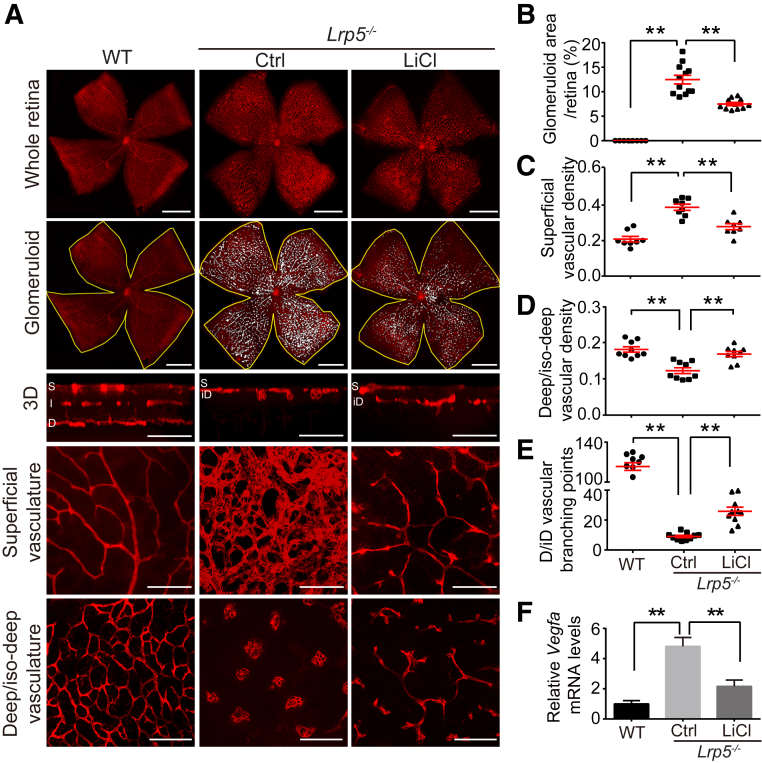

Lithium Treatment Normalizes Deeper Layer Vessels and Ameliorates Pathologic Glomeruloid Vessels in Lrp5−/− Eyes

During the second and third week after birth, the superficial retinal vasculature in mice develops into a finely branched vascular network and, at the same time, extends into the inner retina to form the two deeper capillary networks in the inner and outer plexiform layers36 (Figure 3A). Lrp5−/− mice showed defective vascular migration into the inner retina and displayed a complete absence of intralaminar (intermediate and deep layers of) retinal vessels, as observed at P17 (Figure 3A). This lack of inner retinal vessels was associated with a secondary inner-retinal hypoxia, evidenced by abnormally high levels of retinal vascular endothelial growth factor A (Vegfa) (Figure 3F), which consequently was associated with increased pathologic vascular growth in the superficial plexus with glomeruloid vascular structures (Figure 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

Lithium treatment ameliorates pathologic glomeruloid vascular structures in superficial vascular plexus and partially restores deep layer vasculature in Lrp5−/− eyes. Littermate Lrp5−/− mice were treated with LiCl or vehicle Ctrl daily after birth. Lrp5−/− and age-matched WT mouse retinas were dissected at P17 and stained with isolectin B4 (red). A: Representative images of the whole flat-mounted retinas, retinas (yellow lines) with highlights (white) showing quantified glomeruloid vascular structures, three-dimensional reconstruction of retinal vasculature, enlarged view of selected regions in superficial layer of retinal vascular plexus, and deep or iso-deep layer of retinal vascular plexus. B–E: Quantification of the pathologic glomeruloid area as percentage of the whole retinal area (B), vascular density (vessel coverage area per field) in the superficial layer (C), and deep/iD layer (D), and branching points in the deep/iD layer (E). F: Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of Vegf expression normalized to housekeeping gene 18S and shown as relative levels compared with WT. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 8 to 12 per group (B–E); n = 6 per group (F). ∗∗P < 0.01. Scale bars: 1000 μm (A, whole retina and glomeruloid); 50 μm (A, 3D, superficial vasculature, and deep/iD vasculature). Ctrl, control; D/iD, deep/iso-deep layer; LiCl, lithium chloride; P17, postnatal day 17; WT, wild-type; 3D, three-dimensional.

We next investigated whether longer-term lithium treatment (P1 to P16) may promote normalization of retinal vasculature and pathologic glomeruloid in older Lrp5−/− mice (P17). Retinal flat-mounts showed that Lrp5−/− mice developed pathologic vascular growth in the superficial plexus with glomeruloid vascular structures at P17 (Figure 3A). Lithium treatment significantly reduced the retinal area of glomeruloid vessels (by approximately 60%) compared with vehicle-treated Lrp5−/− littermates (Figure 3, A and B). Lithium treatment also substantially normalized the appearance of finely pruned vessels as well as the abnormally increased vascular density in the superficial vascular layer (Figure 3, A and C). The absence of normal intralaminar vessels in Lrp5−/− retinas was associated with the presence of glomeruloid vessels which migrated slightly from the superficial vessel layer toward what would be the deep plexus. This barely dislocated deeper layer was labeled the iso-deep layer (Figure 3A). Lithium treatment promoted formation of a deep layer in Lrp5−/− retinas, which was completely absent in vehicle-treated littermate mice (Figure 3A). Both vascular density and branching points were significantly normalized in the newly formed deep layer after lithium treatment compared with the iso-deep layer in vehicle-treated littermate Lrp5−/− controls (Figure 3, A, D, and E). These findings suggested that lithium treatment promoted vascular migration from the superficial plexus into the inner retina and improved capillary network formation in a deep vascular layer in Lrp5−/− mice. Improved formation of deeper vasculature layer is likely the primary causes that alleviated the secondary inner retina hypoxia and hypoxia-stimulated Vegfa levels (Figure 3F), which in turn decreased formation of compensatory pathologic glomeruloids in the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3, A and B).

Visual Function Is Dampened in Lrp5−/− Eyes and Lithium Treatment Partially Rescues Visual Function

Retinal vasculature is crucial for normal retinal metabolism and visual function. Having demonstrated that lithium treatment improved retinal vascularization of Lrp5−/− eyes, we next investigated whether visual function was compromised in Lrp5−/− mice and whether lithium treatment improved visual function. ERG was used to measure visual function in P30 mice. In Lrp5−/− mice, b-wave responses (ΔLogNormal) were substantially attenuated compared with age-matched WT controls (Figure 4, A and B), consistent with previous findings showing decreased visual function in a different strain of Lrp5−/− mutant mice.39 Treatment with lithium in Lrp5−/− mice (from P1 to 30) significantly restored b-wave sensitivity (ΔLogNormal) nearly to WT levels (Figure 4, A and B), with modest yet statistically insignificant increase in b-wave amplitude (80.43 ± 4.71 μV in the lithium group versus 64.10 ± 9.35 μV in the vehicle control group) (Figure 4, A and C). These results suggest that visual function was deficient in Lrp5−/− mice, likely due to the absence of intraretinal vessels. Lithium treatment not only protected against retinal vascular abnormalities, but it also partially improved visual function in Lrp5−/− mice.

Figure 4.

Lithium treatment partially rescues visual function and increases retinal thickness in Lrp5−/− eyes. Lrp5−/− mice were treated with LiCl or vehicle (Ctrl) daily from P1 through P30, the day of ERG and OCT measurement. A: Representative ERG waveforms in LiCl- or Ctrl-treated Lrp5−/− mice. B: Quantification of b-wave sensitivity, normalized as Δlog of WT controls. C: Quantification of b-wave amplitude, normalized as Δlog of WT controls. D: Representative original retinal images from OCT (top) and corresponding standardized images (bottom) for thickness measurement. Cyan line indicates NFL; yellow line indicates OPL; red line indicates RPE. E: Quantification of retinal thickness. Thickness of both whole retina (NFL-RPE) and outer retina (OPL-RPE) were analyzed. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 8 to 12 per group (A–C); n = 6 per group (E). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 versus Lrp5−/− + Ctrl. Scale bar = 100 μm (D). Ctrl, control; ERG, electroretinography; LiCl, lithium chloride; NFL, nerve fiber layer; NFL-RPE, distance from NFL to RPE; OCT, optical coherence tomography; OPL, outer plexiform layer; OPL-RPE, distance from OPL to RPE; P1, postnatal day 1; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; WT, wild-type.

Retinal Thickness Decreases in Lrp5−/− Mice and Is Improved by Lithium Treatment

To evaluate whether vascular and functional improvement in lithium-treated Lrp5−/− eyes was accompanied by improved retinal morphology, OCT in vivo imaging was used to evaluate retinal thickness in WT and Lrp5−/− mice treated with lithium from P1 to P30, the day of OCT analysis. Compared with age-matched WT mice, Lrp5−/− eyes showed decreased thickness of the whole retina, measured as the distance from the nerve fiber layer to the retinal pigment epithelium, as well as decreased outer retina thickness, measured from the outer plexiform layer to the retinal pigment epithelium (Figure 4, D and E). Lithium administration partially restored both the whole retinal and inner retinal thickness in Lrp5−/− eyes, compared with vehicle-treated Lrp5−/− littermates (Figure 4, D and E). These data demonstrated morphologic abnormalities in Lrp5−/− eyes and indicated that lithium treatment remedied morphologic abnormalities in Lrp5−/− mice, further corroborating the functional ERG improvement.

Lithium Treatment Restores the Wnt Signaling Deficient in the Lrp5−/− Retina

To evaluate whether lithium activates canonical Wnt signaling in the Lrp5−/− retinas, the relative quantities of proteins in the Wnt signaling pathway were analyzed by Western blot analysis using lysed WT and lithium- and vehicle-treated Lrp5−/− retinas. Proteins indicative of Wnt activation include inactive GSK3β (ie, phosphorylated at Ser-9), active β-catenin (nonphosphorylated), and total β-catenin stabilization. All three markers were significantly decreased in Lrp5−/− retinas (Figure 5). After lithium treatment in Lrp5−/− mice, these indicative Wnt markers returned to levels comparable with WT mice (Figure 5). These results validated that Wnt signaling was decreased in Lrp5−/− retinas and suggested that the protective effects of lithium treatment were likely mediated via restoration of deficient canonical Wnt signaling.

Figure 5.

Wnt signaling is down-regulated in Lrp5−/− retinas and up-regulated by lithium treatment. A: Western blot analysis was performed using retinas from P17 WT and Lrp5−/− mice treated with LiCl or vehicle (Ctrl) daily from P1. Blots were probed using antibodies against Ser9-p-GSK3β, total-GSK3β, non–p-β-catenin, total-β-catenin, and β-actin. B: Densitometry was performed to semiquantify levels of Ser9-p-GSK3β normalized by total-GSK3β levels, and levels of non–p-β-catenin or total-β-catenin normalized by β-actin levels. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 per group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Ctrl, control; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; LiCl, lithium chloride; P17, postnatal day 17; WT, wild-type.

Endothelial Cell Tubular Formation Is Inhibited with LRP5 Suppression and Restored by Lithium Treatment

Previous studies showed that conditional knockout of Lrp5 specifically in vascular endothelium produced virtually identical pathology as systemic Lrp5−/− mice,40 which indicate that endothelial cell function plays a prominent role in FEVR pathologies. To further investigate the mechanisms of lithium's vasoprotective effects, tubular formation assays were performed in vitro using HRMECs. LRP5 siRNA was used to knock down LRP5, which effectively suppressed LRP5 mRNA expression and inhibited Wnt signaling (Figure 6, A–C), without affecting cell viability (Supplemental Figure S1). Lithium treatment significantly reactivated Wnt signaling in LRP5-deficient cells (Figure 6, B and C), without affecting cell viability at the experimental dose (10 mmol/L; Supplemental Figure S2C). Moreover, LRP5 siRNA significantly decreased branching point number and vessel length in a vascular tubule formation assay compared with negative control siRNA, and lithium treatment significantly enhanced branching point number and vessel length in both the control and LRP5 siRNA groups (Figure 6, D and E). This demonstrates that lithium restored the downstream canonical Wnt signaling pathway and improved endothelial cell tubular formation in an LRP5-independent manner.

Figure 6.

Lithium improves endothelial cell tubular formation in vitro. HRMECs were transfected with negative si-Ctrl or si-LRP5 for 48 hours and then treated with LiCl or NaCl (Ctrl) for another 24 hours before further experiments. A: Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of LRP5 mRNA expression normalized to housekeeping gene 18S and shown as relative levels compared with si-Ctrl. B: Western blot analysis of HRMECs with si-Ctrl/si-LRP5 transfection and Ctrl/LiCl treatment. Blots were probed using antibodies against Ser9-p-GSK3β, total-GSK3β, non–p-β-catenin, total-β-catenin, and β-actin. C: Densitometry was performed to semiquantify levels of ser9-p-GSK3β normalized by total-GSK3β levels, and levels of non–p-β-catenin or total-β-catenin normalized by β-actin levels. D: Representative images of endothelial cell tubular formation, with or without si-Ctrl/si-LRP5 transfection and Ctrl/LiCl treatment. E: Quantification of vascular branching points and total vessel length (μm) per field in HRMEC tubular formation Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 3 per group (C and E). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Scale bar = 200 μm (D). Ctrl, control; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; HRMEC, Human retinal microvascular endothelial cell; LiCl, lithium chloride; LRP5, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5; si-Ctrl, control siRNA; si, LRP5, LRP5 siRNA; NaCl, sodium chloride.

Analysis of Potential Adverse Systemic Effects of Lithium Treatment

Decades of lithium usage in treating bipolar and depressive disorders suggest its pharmaceutical safety.41 Similarly, in our study we observed no adverse effects of lithium on mouse body weight gain (Supplemental Figure S2A) or other detrimental effects at the experimental dose (10 mg lithium chloride/kg body weight), which is comparable with the suggested clinical use of lithium (10 to 20 mg/kg lithium carbonate per day).42 A higher dose (50 mg/kg) of lithium showed moderate negative effects on body weight after 9 days of treatment (Supplemental Figure S2B). However, despite the decelerated weight gain, treatment with the higher dose also showed significant vasoprotective effects with decreased pathologic glomeruloids and improved vascular density in the superficial vascular layer at P17 (Supplemental Figure S3).

Discussion

Our study presents thorough characterizations of vascular, functional, and morphologic pathologies in Lrp5−/− mouse eyes, an animal model of FEVR. Moreover, we identified a novel approach for treating FEVR disease through receptor-independent activation of Wnt signaling by using a Food and Drug Administration–approved drug, lithium. This is supported by both morphologic and functional improvement in lithium-treated Lrp5−/− mice. Our data demonstrated that lithium activated Wnt signaling in an LRP5-indepdent manner, thereby bypassing the genetic defect to effectively rescue defective retinal vasculature in Lrp5−/− mice. The vascular improvement includes early, modest acceleration of retinal vascular growth in the superficial plexus vascular formation, partial yet significant restoration of absent inner retinal vasculature, and later, substantial reduction of pathologic glomeruloids in the superficial vasculature plexus. Our data also indicate that lithium treatment partially rescued visual function and increased retinal thickness in Lrp5−/− mice. All these findings suggest that activation of Wnt signaling by lithium normalized ocular vascular pathologies in Lrp5−/− mice, providing a potential treatment approach for FEVR.

In addition to rescuing the defects of retinal vascular development, our data demonstrated that lithium treatment also promoted regression of hyaloid vasculature in Lrp5−/− mice, persistence of which may lead to blocking of the optical path.38, 43 The positive effect of Wnt activator on hyaloid vessel regression is potentially relevant for not only FEVR but also other eye diseases with persistent fetal vasculature, previously known as persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous.44 The pathogenesis of persistent fetal vasculature is still poorly understood, although Wnt-dependent and macrophage-mediated endothelial cell apoptosis was a major mechanism suggested in mediating hyaloid regression.38

To date, FEVR has been primarily linked with mutations in not only LRP5 but also several other genes in the interrelated Wnt signaling pathway, including autosomal dominant Wnt receptor frizzled4 (FZD4) mutation,5, 45 X-linked recessive mutation of the Wnt ligand Norrin,6, 46, 47, 48 and autosomal dominant or recessive TSPAN12 mutations.49, 50, 51 All of these genes are involved in the very first step of Wnt ligand/receptor complex formation and signaling initiation. Mice deficient in Lrp5, Fzd4, Norrin, or Tspan12 all display similar retinal vascular phenotypes, including delayed vascular development, persistent hyaloid vasculature, lack of inner retinal vasculature, and impaired visual function.6, 17, 49 Although genetic overexpression of Norrin52, 53 or stabilization of β-catenin40 were found to be effective in rescuing vascular defects in Norrin-deficient mice, no pharmacologic treatments have yet been identified for FEVR or Norrie disease. Future investigations will determine whether lithium treatment is also effective in genetic models of FEVR other than Lrp5−/− mice. Interestingly recent work also associated FEVR with new genetic mutations in kinesin superfamily protein 11 (KIF11)54 and zinc finger protein 408 (ZNF408),55 that are not directly related to Wnt pathway. Whether these novel genes regulate retinal vasculogenesis through indirect interaction with Wnt signaling or completely independent of Wnt pathway will await further investigation.

Although insufficient Wnt signaling causes inadequate angiogenesis in the eye, such as seen in FEVR, pathologically increased Wnt signaling was found to be detrimental for promoting pathologic neovascularization in proliferative retinopathies and neovascular age-related macular degeneration models,12, 34, 56, 57, 58 suggesting a functionally plastic role of Wnt signaling in ocular angiogenesis. As one of the most important pathways in angiogenesis regulation,59, 60 proper balance of Wnt signaling appears to be essential for building and maintaining a functional ocular vasculature to ensure visual function.61 It is therefore critical to carefully titrate Wnt signaling and to promote it when it is deficient, as in this study with lithium treatment in Lrp5−/− mice, whereas when Wnt signaling is abnormally up-regulated in other disease settings, it needs to be suppressed to the normal levels to prevent pathologic neovascularization.11, 12 This dual, opposing role of Wnt signaling is similar to the role of VEGF, which is essential for physiological vascular development and maintenance, and yet can be detrimental in pathologic conditions when up-regulated abnormally. In the absence of Wnt signaling in Lrp5−/− retina, a compensatory VEGF elevation was observed, reflecting secondary hypoxia response in the lack of intralaminar vasculature, consistent with previous report of hypoxia-induced VEGF production in mice deficient of Norrin/Frizzled4 signaling.62 Lithium treatment alleviated the VEGF induction in Lrp5−/− retina, likely through partially improved deeper vascular layers, thereby resulting in suppressed pathologic glomeruloids at the vitreal surface of the retina.

Our data indicate that lithium treatment not only promoted normalization of retinal vasculature in Lrp5−/− mice but also improved visual function, particularly the sensitivity of the ERG b-wave response, associated with partially restored retinal thickness. Because the b-wave primarily originates in bipolar cells in the inner retina, our results indicate that lithium partially improved retinal visual function in Lrp5−/− mice, in particular in the inner retina. This observation is consistent with the morphologic localization of the intralaminar vascular improvement, which is expected to have the most pronounced effect in the inner retina. Therefore the functional neuronal improvement is likely mediated through secondary effects resultant from improved vasculature by lithium treatment. Proangiogenic effects of lithium were demonstrated in our endothelial cell culture and also in previous studies in embryonic vessels in vivo and in endothelial cells in vitro.63, 64 Our data suggest that lithium's vascular effects were likely mediated primarily through activation of the Wnt signaling pathway, by inhibiting the secondary Wnt signaling complex containing GSK3β, thus stabilizing the downstream factor β-catenin to eventually promote vascular formation. However, it is not clear whether potential Wnt/GSK3-independent effects of lithium may also be at work, including those through inositol depletion,65 bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2 signaling,66 transcription factor 7-like 2 gene RNA splicing,67 or mitogen-activated protein (MAP) extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) kinase (MEK)-ERK pathway.68 In addition, direct neuronal effects of lithium are also possible because lithium was found to protect neurons and to promote synaptic formation.69, 70 The relatively modest improvement of b-wave amplitude by lithium was potentially negated by its direct suppressive effects on neuronal synaptic transmission, which is the primary rationale of its use to treat bipolar disease and mental disorders.71

Although the incidence of FEVR is rare, the impact of vision impairment on the life quality of patients with severe FEVR is quite high, especially because they may experience vision impairment very early in life.72 Patients with FEVR usually have a family history and hence may be diagnosed early, yet intervention options remain quite limited. Experimental studies of potential treatment for FEVR are also lacking. Our work is the first proof-of-concept study to demonstrate that receptor-independent activation of Wnt signaling by a small molecular drug can, at least partially, normalize the development of the retinal vasculature and preserve retinal function in a mouse model of FEVR. Future investigation is needed to ascertain whether lithium may be effective in humans. Additional investigation of more potent Wnt activators and better local delivery approach may provide even stronger protection with less potential systemic side effects. Although retinal vasculature develops postnatally in mice, human retinal vessels develop in utero; therefore, additional studies would be needed to determine whether this approach is safe for fetuses and infants, even though lithium is considered the first-choice agent for treating bipolar disorder during pregnancy.73 Nevertheless, the concept of bypassing the genetic defects of Wnt ligand/receptors and targeting the downstream pathway may also be of value in developing treatment strategies for other diseases with defective Wnt signaling, such as osteoporosis.74

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lois E.H. Smith for helpful discussion and critical editing of the manuscript; Christian G. Hurst, Lucy P. Evans, and Xuhua Fan for excellent technical support; and Dr. Richard A. Lang for providing the hyaloid isolation protocol.

Z.W. and J.C. conceived and designed the research, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; C.-H.L., Y.S., Y.G., T.L.F., P.C.M., N.J.S., and T.W.F. collected and analyzed data; X.H. provided expert advice and wrote the manuscript; J.D.A. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; all authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH/National Eye Institute grant R01 EY024963, Boston Children's Hospital Ophthalmology Foundation, Massachusetts Lions Eye Research Fund, Inc., and Alcon Research Institute (J.C.); a Chinese Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology Postdoctoral Research Abroad Fellowship 104-2917-I-564-026 (C.-H.L.); and NIH grants RO1-GM057603 and RO1-AR060359 and Boston Children's Hospital Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center funded by NIH grant P30 HD-18655 (X.H.). X.H. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.06.015.

Supplemental Data

Knocking down LRP5 in HRMECs does not affect cell viability. HRMECs were transfected with negative Ctrl-siRNA or LRP5-siRNA for 48 hours and then treated with LiCl or NaCl (Ctrl) for another 24 hours. A: Cells were subjected to MTT assay, and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured for cell viability, B: Cells were stained with trypan blue and counted by an automated cell counter to determine live cell numbers. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 8 wells per group (A); n = 3 wells per group (B). Ctrl, control; HRMEC, Human retinal microvascular endothelial cell; LiCl, lithium chloride; LRP5, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5; NaCl, sodium chloride.

Effects of different doses of lithium treatment on mouse body weight in vivo and on endothelial cell viability in vitro. A and B: Littermate Lrp5−/− pups were treated intraperitoneally with LiCl or vehicle (Ctrl) daily from P1. Body weight was monitored daily. A: A lower dose of LiCl treatment (10 mg/kg body weight) shows no significant adverse effect on body weight. B: A higher dose of LiCl treatment (50 mg/kg body weight) shows moderate yet significant adverse effect on body weight gain starting from P9. C: HRMECs were treated with LiCl or NaCl (as Ctrl) at different concentrations. MTT assay was performed to measure cell viability. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (B), means ± SD (C). n = 3 to 5 mice per group (A and B); n = 3 per group (C). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 by unpaired t-test; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test. Ctrl, control; HRMEC, human retinal microvascular endothelial cell; LiCl, lithium chloride; NaCl, sodium chloride; P1, postnatal day 1.

High dose of LiCl treatment also ameliorates pathologic glomeruloid in Lrp5−/− eyes. Littermate Lrp5−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with 50 mg/kg body weight LiCl or vehicle control (phosphate-buffered saline) daily from P1 through sacrifice at P17. Retinas were dissected and stained with isolectin B4 (red). A: Representative images of the whole flat-mounted retinas, and retinas with pathologic glomeruloid highlighted (white) for quantification. Total retinal areas were marked with a yellow line. B and C: Quantification of pathologic glomeruloid areas as a percentage of the whole retinal area (B) and vascular density (vessel coverage area per field) in the superficial layer (C). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 8 mice per group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 by unpaired t-test. Scale bar = 1000 μm. Ctrl, control; LiCl, lithium chloride; P1, postnatal day 1.

References

- 1.Toomes C., Downey L. Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy, Autosomal Dominant. In: Pagon R.A., Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H., Bird T.D., Dolan C.R., Fong C.T., Smith R.J.H., Stephens K., editors. GeneReviews(R) University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye X., Wang Y., Nathans J. The Norrin/Frizzled4 signaling pathway in retinal vascular development and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson W.E. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1995;93:473–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gal M., Levanon E.Y., Hujeirat Y., Khayat M., Pe'er J., Shalev S. Novel mutation in TSPAN12 leads to autosomal recessive inheritance of congenital vitreoretinal disease with intra-familial phenotypic variability. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:2996–3002. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toomes C., Bottomley H.M., Jackson R.M., Towns K.V., Scott S., Mackey D.A., Craig J.E., Jiang L., Yang Z., Trembath R., Woodruff G., Gregory-Evans C.Y., Gregory-Evans K., Parker M.J., Black G.C., Downey L.M., Zhang K., Inglehearn C.F. Mutations in LRP5 or FZD4 underlie the common familial exudative vitreoretinopathy locus on chromosome 11q. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:721–730. doi: 10.1086/383202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Q., Wang Y., Dabdoub A., Smallwood P.M., Williams J., Woods C., Kelley M.W., Jiang L., Tasman W., Zhang K., Nathans J. Vascular development in the retina and inner ear: control by Norrin and Frizzled-4, a high-affinity ligand-receptor pair. Cell. 2004;116:883–895. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dejana E. The role of wnt signaling in physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2010;107:943–952. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Iongh R.U., Abud H.E., Hime G.R. WNT/Frizzled signaling in eye development and disease. Front Biosci. 2006;11:2442–2464. doi: 10.2741/1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warden S.M., Andreoli C.M., Mukai S. The Wnt signaling pathway in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and Norrie disease. Semin Ophthalmol. 2007;22:211–217. doi: 10.1080/08820530701745124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon R.T., Kohn A.D., De Ferrari G.V., Kaykas A. WNT and beta-catenin signalling: diseases and therapies. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:691–701. doi: 10.1038/nrg1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J., Stahl A., Krah N.M., Seaward M.R., Dennison R.J., Sapieha P., Hua J., Hatton C.J., Juan A.M., Aderman C.M., Willett K.L., Guerin K.I., Mammoto A., Campbell M., Smith L.E. Wnt signaling mediates pathological vascular growth in proliferative retinopathy. Circulation. 2011;124:1871–1881. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.040337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z., Cheng R., Lee K., Tyagi P., Ding L., Kompella U.B., Chen J., Xu X., Ma J.X. Nanoparticle-mediated expression of a Wnt pathway inhibitor ameliorates ocular neovascularization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:855–864. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X., Semenov M., Tamai K., Zeng X. LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: arrows point the way. Development. 2004;131:1663–1677. doi: 10.1242/dev.01117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDonald B.T., He X. Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson W.J., Nusse R. Convergence of Wnt, beta-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science. 2004;303:1483–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.1094291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logan C.Y., Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J., Stahl A., Krah N.M., Seaward M.R., Joyal J.S., Juan A.M., Hatton C.J., Aderman C.M., Dennison R.J., Willett K.L., Sapieha P., Smith L.E. Retinal expression of Wnt-pathway mediated genes in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (Lrp5) knockout mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye X., Wang Y., Cahill H., Yu M., Badea T.C., Smallwood P.M., Peachey N.S., Nathans J. Norrin, frizzled-4, and Lrp5 signaling in endothelial cells controls a genetic program for retinal vascularization. Cell. 2009;139:285–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Nouhuys C.E. Juvenile retinal detachment as a complication of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Fortschr Ophthalmol. 1989;86:221–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamane T., Yokoi T., Nakayama Y., Nishina S., Azuma N. Surgical outcomes of progressive tractional retinal detachment associated with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato M., Patel M.S., Levasseur R., Lobov I., Chang B.H., Glass D.A., II, Hartmann C., Li L., Hwang T.H., Brayton C.F., Lang R.A., Karsenty G., Chan L. Cbfa1-independent decrease in osteoblast proliferation, osteopenia, and persistent embryonic eye vascularization in mice deficient in Lrp5, a Wnt coreceptor. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:303–314. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein P.S., Melton D.A. A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8455–8459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller-Oerlinghausen B., Felber W., Berghofer A., Lauterbach E., Ahrens B. The impact of lithium long-term medication on suicidal behavior and mortality of bipolar patients. Arch Suicide Res. 2005;9:307–319. doi: 10.1080/13811110590929550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J., Connor K.M., Aderman C.M., Smith L.E. Erythropoietin deficiency decreases vascular stability in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:526–533. doi: 10.1172/JCI33813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stahl A., Connor K.M., Sapieha P., Willett K.L., Krah N.M., Dennison R.J., Chen J., Guerin K.I., Smith L.E. Computer-aided quantification of retinal neovascularization. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9155-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connor K.M., Krah N.M., Dennison R.J., Aderman C.M., Chen J., Guerin K.I., Sapieha P., Stahl A., Willett K.L., Smith L.E. Quantification of oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse: a model of vessel loss, vessel regrowth and pathological angiogenesis. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang N., Favazza T.L., Baglieri A.M., Benador I.Y., Noonan E.R., Fulton A.B., Hansen R.M., Iuvone P.M., Akula J.D. The rat with oxygen-induced retinopathy is myopic with low retinal dopamine. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:8275–8284. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hood D.C., Birch D.G. Rod phototransduction in retinitis pigmentosa: estimation and interpretation of parameters derived from the rod a-wave. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:2948–2961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamb T.D., Pugh E.N., Jr. A quantitative account of the activation steps involved in phototransduction in amphibian photoreceptors. J Physiol. 1992;449:719–758. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pugh E.N., Jr., Lamb T.D. Amplification and kinetics of the activation steps in phototransduction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1141:111–149. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90038-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fulton A.B., Rushton W.A. The human rod ERG: correlation with psychophysical responses in light and dark adaptation. Vision Res. 1978;18:793–800. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(78)90119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akula J.D., Mocko J.A., Benador I.Y., Hansen R.M., Favazza T.L., Vyhovsky T.C., Fulton A.B. The neurovascular relation in oxygen-induced retinopathy. Mol Vis. 2008;14:2499–2508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun Y., Ju M., Lin Z., Fredrick T.W., Evans L.P., Tian K.T., Saba N.J., Morss P.C., Pu W.T., Chen J., Stahl A., Joyal J.S., Smith L.E. SOCS3 in retinal neurons and glial cells suppresses VEGF signaling to prevent pathological neovascular growth. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra94. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa8695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z., Moran E., Ding L., Cheng R., Xu X., Ma J.X. PPARalpha regulates mobilization and homing of endothelial progenitor cells through the HIF-1alpha/SDF-1 pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:3820–3832. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu C.H., Sun Y., Li J., Gong Y., Tian K.T., Evans L.P., Morss P.C., Fredrick T.W., Saba N.J., Chen J. Endothelial microRNA-150 is an intrinsic suppressor of pathologic ocular neovascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:12163–12168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508426112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stahl A., Connor K.M., Sapieha P., Chen J., Dennison R.J., Krah N.M., Seaward M.R., Willett K.L., Aderman C.M., Guerin K.I., Hua J., Lofqvist C., Hellstrom A., Smith L.E. The mouse retina as an angiogenesis model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2813–2826. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Downey L.M., Bottomley H.M., Sheridan E., Ahmed M., Gilmour D.F., Inglehearn C.F., Reddy A., Agrawal A., Bradbury J., Toomes C. Reduced bone mineral density and hyaloid vasculature remnants in a consanguineous recessive FEVR family with a mutation in LRP5. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1163–1167. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.092114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lobov I.B., Rao S., Carroll T.J., Vallance J.E., Ito M., Ondr J.K., Kurup S., Glass D.A., Patel M.S., Shu W., Morrisey E.E., McMahon A.P., Karsenty G., Lang R.A. WNT7b mediates macrophage-induced programmed cell death in patterning of the vasculature. Nature. 2005;437:417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature03928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia C.H., Yablonka-Reuveni Z., Gong X. LRP5 is required for vascular development in deeper layers of the retina. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Y., Wang Y., Tischfield M., Williams J., Smallwood P.M., Rattner A., Taketo M.M., Nathans J. Canonical WNT signaling components in vascular development and barrier formation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3825–3846. doi: 10.1172/JCI76431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amsterdam J.D., Lorenzo-Luaces L., Soeller I., Li S.Q., Mao J.J., DeRubeis R.J. Safety and effectiveness of continuation antidepressant versus mood stabilizer monotherapy for relapse-prevention of bipolar II depression: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rouillon F., Gorwood P. The use of lithium to augment antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 5:32–39. discussion 40–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saint-Geniez M., D'Amore P.A. Development and pathology of the hyaloid, choroidal and retinal vasculature. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:1045–1058. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041895ms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shastry B.S. Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous: congenital malformation of the eye. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2009;37:884–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robitaille J., MacDonald M.L., Kaykas A., Sheldahl L.C., Zeisler J., Dube M.P., Zhang L.H., Singaraja R.R., Guernsey D.L., Zheng B., Siebert L.F., Hoskin-Mott A., Trese M.T., Pimstone S.N., Shastry B.S., Moon R.T., Hayden M.R., Goldberg Y.P., Samuels M.E. Mutant frizzled-4 disrupts retinal angiogenesis in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Nat Genet. 2002;32:326–330. doi: 10.1038/ng957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Z.Y., Battinelli E.M., Fielder A., Bundey S., Sims K., Breakefield X.O., Craig I.W. A mutation in the Norrie disease gene (NDP) associated with X-linked familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Nat Genet. 1993;5:180–183. doi: 10.1038/ng1093-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shastry B.S., Hejtmancik J.F., Trese M.T. Identification of novel missense mutations in the Norrie disease gene associated with one X-linked and four sporadic cases of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:396–401. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:5<396::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shastry B.S., Hejtmancik J.F., Plager D.A., Hartzer M.K., Trese M.T. Linkage and candidate gene analysis of X-linked familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Genomics. 1995;27:341–344. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Junge H.J., Yang S., Burton J.B., Paes K., Shu X., French D.M., Costa M., Rice D.S., Ye W. TSPAN12 regulates retinal vascular development by promoting Norrin- but not Wnt-induced FZD4/beta-catenin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poulter J.A., Ali M., Gilmour D.F., Rice A., Kondo H., Hayashi K., Mackey D.A., Kearns L.S., Ruddle J.B., Craig J.E., Pierce E.A., Downey L.M., Mohamed M.D., Markham A.F., Inglehearn C.F., Toomes C. Mutations in TSPAN12 cause autosomal-dominant familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikopoulos K., Gilissen C., Hoischen A., van Nouhuys C.E., Boonstra F.N., Blokland E.A., Arts P., Wieskamp N., Strom T.M., Ayuso C., Tilanus M.A., Bouwhuis S., Mukhopadhyay A., Scheffer H., Hoefsloot L.H., Veltman J.A., Cremers F.P., Collin R.W. Next-generation sequencing of a 40 Mb linkage interval reveals TSPAN12 mutations in patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohlmann A., Scholz M., Goldwich A., Chauhan B.K., Hudl K., Ohlmann A.V., Zrenner E., Berger W., Cvekl A., Seeliger M.W., Tamm E.R. Ectopic norrin induces growth of ocular capillaries and restores normal retinal angiogenesis in Norrie disease mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1701–1710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4756-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y., Rattner A., Zhou Y., Williams J., Smallwood P.M., Nathans J. Norrin/Frizzled4 signaling in retinal vascular development and blood brain barrier plasticity. Cell. 2012;151:1332–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu H., Xiao X., Li S., Jia X., Guo X., Zhang Q. KIF11 mutations are a common cause of autosomal dominant familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:278–283. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Collin R.W., Nikopoulos K., Dona M., Gilissen C., Hoischen A., Boonstra F.N., Poulter J.A., Kondo H., Berger W., Toomes C., Tahira T., Mohn L.R., Blokland E.A., Hetterschijt L., Ali M., Groothuismink J.M., Duijkers L., Inglehearn C.F., Sollfrank L., Strom T.M., Uchio E., van Nouhuys C.E., Kremer H., Veltman J.A., van Wijk E., Cremers F.P. ZNF408 is mutated in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and is crucial for the development of zebrafish retinal vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9856–9861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220864110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qi W., Yang C., Dai Z., Che D., Feng J., Mao Y., Cheng R., Wang Z., He X., Zhou T., Gu X., Yan L., Yang X., Ma J.X., Gao G. High levels of pigment epithelium-derived factor in diabetes impair wound healing through suppression of Wnt signaling. Diabetes. 2015;64:1407–1419. doi: 10.2337/db14-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou T., Hu Y., Chen Y., Zhou K.K., Zhang B., Gao G., Ma J.X. The pathogenic role of the canonical Wnt pathway in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4371–4379. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tuo J., Wang Y., Cheng R., Li Y., Chen M., Qiu F., Qian H., Shen D., Penalva R., Xu H., Ma J.X., Chan C.C. Wnt signaling in age-related macular degeneration: human macular tissue and mouse model. J Transl Med. 2015;13:330. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0683-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ring A., Kim Y.M., Kahn M. Wnt/catenin signaling in adult stem cell physiology and disease. Stem Cell Rev. 2014;10:512–525. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9515-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reis M., Liebner S. Wnt signaling in the vasculature. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Masckauchan T.N., Kitajewski J. Wnt/Frizzled signaling in the vasculature: new angiogenic factors in sight. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:181–188. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00058.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rattner A., Wang Y., Zhou Y., Williams J., Nathans J. The role of the hypoxia response in shaping retinal vascular development in the absence of Norrin/Frizzled4 signaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:8614–8625. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zeilbeck L.F., Muller B., Knobloch V., Tamm E.R., Ohlmann A. Differential angiogenic properties of lithium chloride in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Birdsey G.M., Shah A.V., Dufton N., Reynolds L.E., Osuna Almagro L., Yang Y., Aspalter I.M., Khan S.T., Mason J.C., Dejana E., Gottgens B., Hodivala-Dilke K., Gerhardt H., Adams R.H., Randi A.M. The endothelial transcription factor ERG promotes vascular stability and growth through Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Dev Cell. 2015;32:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harwood A.J. Lithium and bipolar mood disorder: the inositol-depletion hypothesis revisited. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:117–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li J., Khavandgar Z., Lin S.H., Murshed M. Lithium chloride attenuates BMP-2 signaling and inhibits osteogenic differentiation through a novel WNT/GSK3- independent mechanism. Bone. 2011;48:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Struewing I., Boyechko T., Barnett C., Beildeck M., Byers S.W., Mao C.D. The balance of TCF7L2 variants with differential activities in Wnt-signaling is regulated by lithium in a GSK3beta-independent manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pardo R., Andreolotti A.G., Ramos B., Picatoste F., Claro E. Opposed effects of lithium on the MEK-ERK pathway in neural cells: inhibition in astrocytes and stimulation in neurons by GSK3 independent mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2003;87:417–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nonaka S., Hough C.J., Chuang D.M. Chronic lithium treatment robustly protects neurons in the central nervous system against excitotoxicity by inhibiting N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated calcium influx. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2642–2647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim H.J., Thayer S.A. Lithium increases synapse formation between hippocampal neurons by depleting phosphoinositides. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:1021–1030. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mertens J., Wang Q.W., Kim Y., Yu D.X., Pham S., Yang B., Zheng Y., Diffenderfer K.E., Zhang J., Soltani S., Eames T., Schafer S.T., Boyer L., Marchetto M.C., Nurnberger J.I., Calabrese J.R., Odegaard K.J., McCarthy M.J., Zandi P.P., Alda M., Nievergelt C.M., Pharmacogenomics of Bipolar Disorder Study. Mi S., Brennand K.J., Kelsoe J.R., Gage F.H., Yao J. Differential responses to lithium in hyperexcitable neurons from patients with bipolar disorder. Nature. 2015;527:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nature15526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gilmour D.F. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and related retinopathies. Eye. 2015;29:1–14. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gentile S. Lithium in pregnancy: the need to treat, the duty to ensure safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11:425–437. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2012.670419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Clement-Lacroix P., Ai M., Morvan F., Roman-Roman S., Vayssiere B., Belleville C., Estrera K., Warman M.L., Baron R., Rawadi G. Lrp5-independent activation of Wnt signaling by lithium chloride increases bone formation and bone mass in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17406–17411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505259102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Knocking down LRP5 in HRMECs does not affect cell viability. HRMECs were transfected with negative Ctrl-siRNA or LRP5-siRNA for 48 hours and then treated with LiCl or NaCl (Ctrl) for another 24 hours. A: Cells were subjected to MTT assay, and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured for cell viability, B: Cells were stained with trypan blue and counted by an automated cell counter to determine live cell numbers. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 8 wells per group (A); n = 3 wells per group (B). Ctrl, control; HRMEC, Human retinal microvascular endothelial cell; LiCl, lithium chloride; LRP5, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5; NaCl, sodium chloride.

Effects of different doses of lithium treatment on mouse body weight in vivo and on endothelial cell viability in vitro. A and B: Littermate Lrp5−/− pups were treated intraperitoneally with LiCl or vehicle (Ctrl) daily from P1. Body weight was monitored daily. A: A lower dose of LiCl treatment (10 mg/kg body weight) shows no significant adverse effect on body weight. B: A higher dose of LiCl treatment (50 mg/kg body weight) shows moderate yet significant adverse effect on body weight gain starting from P9. C: HRMECs were treated with LiCl or NaCl (as Ctrl) at different concentrations. MTT assay was performed to measure cell viability. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (B), means ± SD (C). n = 3 to 5 mice per group (A and B); n = 3 per group (C). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 by unpaired t-test; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test. Ctrl, control; HRMEC, human retinal microvascular endothelial cell; LiCl, lithium chloride; NaCl, sodium chloride; P1, postnatal day 1.

High dose of LiCl treatment also ameliorates pathologic glomeruloid in Lrp5−/− eyes. Littermate Lrp5−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with 50 mg/kg body weight LiCl or vehicle control (phosphate-buffered saline) daily from P1 through sacrifice at P17. Retinas were dissected and stained with isolectin B4 (red). A: Representative images of the whole flat-mounted retinas, and retinas with pathologic glomeruloid highlighted (white) for quantification. Total retinal areas were marked with a yellow line. B and C: Quantification of pathologic glomeruloid areas as a percentage of the whole retinal area (B) and vascular density (vessel coverage area per field) in the superficial layer (C). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 8 mice per group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 by unpaired t-test. Scale bar = 1000 μm. Ctrl, control; LiCl, lithium chloride; P1, postnatal day 1.