Abstract

Background

Ginsenoside Rg1 is a class of steroid glycoside and triterpene saponin in Panax ginseng. Many studies suggest that Rg1 suppresses adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1. However, the detail molecular mechanism of Rg1 on adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 is still not fully understood.

Methods

3T3-L1 preadipocyte was used to evaluate the effect of Rg1 on adipocyte development in the differentiation in a stage-dependent manner in vitro. Oil Red O staining and Nile red staining were conducted to measure intracellular lipid accumulation and superoxide production, respectively. We analyzed the protein expression using Western blot in vitro. The zebrafish model was used to investigate whether Rg1 suppresses the early stage of fat accumulation in vivo.

Results

Rg1 decreased lipid accumulation in early-stage differentiation of 3T3-L1 compared with intermediate and later stages of adipocyte differentiation. Rg1 dramatically increased CAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) homologous protein-10 (CHOP10) and subsequently reduced the C/EBPβ transcriptional activity that prohibited the initiation of adipogenic marker expression as well as triglyceride synthase. Rg1 decreased the expression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and glycogen synthase kinase 3β, which are also essential for stimulating the expression of CEBPβ. Rg1 also reduced reactive oxygen species production because of the downregulated protein level of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen (NADPH) oxidase 4 (NOX4). While Rg1 increased the endogenous antioxidant enzymes, it also dramatically decreased the accumulation of lipid and triglyceride in high fat diet-induced obese zebrafish.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that Rg1 suppresses early-stage differentiation via the activation of CHOP10 and attenuates fat accumulation in vivo. These results indicate that Rg1 might have the potential to reduce body fat accumulation in the early stage of obesity.

Keywords: 3T3-L1, obesity, reactive oxygen species, Rg1, zebrafish

Abbreviations: CON, control; ND, nondifferentiated preadipocyte

1. Introduction

High fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity is a serious public health problem worldwide, and is an underlying factor of metabolic syndrome as well as multiple postmodern noncommunicable diseases [1]. Body fat accumulation is caused by different of processes including hyperplasia and hypertrophic in obesity [2]. Hyperplasia and hypertrophic adipocyte are induced as a result of adipogenesis, which is the process of adipocyte differentiation for cell proliferation and lipid accumulation [3]. During the mitotic clonal expansion phase, which is the early stage of adipogenesis in adipocyte, CAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ; which starts to coordinate the multiple transcriptional regulation by turning on major adipogenic factors), C/EBPα, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) are expressed [4], [5]. Moreover, adipogenic factors markedly upregulates the adipocyte protein 2 (aP2) and triglyceride synthesis enzymes such as lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase (LPAT), Lipin1, and diacylglycerolacyltransferase 1 (DGAT1) during the late stage of adipogenesis [6], [7].

The development of adipocyte is also associated with an oxidative stress in obesity [8]. The abundance of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which is generated by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen (NADPH) oxidase 4 (NOX4) during adipogenesis, leads to increased cellular damage and insulin resistance [9], [10]. By contrast, the endogenous antioxidant enzymes, such as the enzyme superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), SOD2, catalase (CAT) glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and glutathione reductase (GR), have been reported to lead to low levels of enzymes in obese mice [11].

Recently, it has been reported that ROS is important in stimulating the mitotic clonal expansion (MCE) during adipogenesis by increasing the C/EBPβ activity [12]. Moreover, C/EBP homologous protein-10 (CHOP10) functions as a negative regulator of C/EBPβ in the early stage of adipogenesis [13]. Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), which include three groups—extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), c-Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK), and p38 MAPK, are intracellular signaling pathways that play a pivotal role in many essential cellular processes such as proliferation and differentiation [14]. The phosphorylation of ERK regulates cell proliferation and is required to induce the expression of C/EBPβ for initiating the differentiation process in the early stage of adipogenesis [15], [16]. Moreover, phosphorylation of C/EBPβ at a consensus ERK/glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) site is required for the activation of primary adipogenic factor expression including C/EBPα, PPARγ, and aP2 [17]. Therefore, regulation of the early stage of marker C/EBPβ is important to suppress the development of adipocyte in obese individuals.

The higher intake of fruits and herbs in comparison with HFD is correlated with a dramatically decreased risk of obesity and obesity-associated noncommunicable diseases [18]. These fruits and herbs contain numerous bioactive compounds that have the potential to be used as therapeutic agents for noncommunicable diseases including obesity [19], [20].

Panax ginseng is a traditional herbal medicine used around the world. Ginsenoside is an active component of P. ginseng and has been elucidated to have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, and antidiabetes effects [21], [22], [23]. Rg1 is a triterpene saponin and one of the principal active compounds extracted from P. ginseng. Recently, we and other groups reported that Rg1 stimulates glucose uptake, mitigates oxidative stress in rat skeletal muscles and suppresses triglyceride accumulation in 3T3-L1 [24], [25], [26]. However, the underlying contribution of Rg1 to the early stage of adipogenesis and ROS promotion remains unclear.

Thus, we investigated how Rg1 regulates the aforementioned gene expression including adipocyte differentiation makers, antioxidant enzymes, CHOP10, and GSK3β in the development of 3T3-L1 in a stage-dependent manner. Moreover, we have evaluated the effect of Rg1 on lipid and triglyceride accumulation in the HFD-induced obese zebrafish model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Ginsenoside Rg1 (≥95% purity) was purchased from ChengDu Biopurify Phytochemicals Ltd. (Biopurify, ChengDu, China). 3T3-L1 preadipocyte was purchased from the ATCC (CL-173; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), bovine calf serum (BCS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin–streptomycin (P/S), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and trypsin–EDTA were purchased from Gibco (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Dexamethasone (DEX), 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), insulin, Oil Red O, nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), and N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Peroxide-sensitive fluorophore 2,7′-dichlorodihydrofluoresceindiacetate (DCF-DA) was purchased from Cell Biolabs (San Diego, CA, USA). 2,3-Bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carbox-anilide (XTT) reagent and N-methyl dibenzopyrazine methyl sulfate (PMS) were purchased from Welgene (Gyeongsan, South Korea). Unless noted otherwise, all chemicals were also purchased from Sigma Chemical Co.

Antibodies specific for aP2, JNK, p38MAPK, phospho-p38MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), ERK1/2, and GPx were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against CHOP10, C/EBPβ, C/EBPα, PPARγ, LPAT, Lipin1, DGAT1, phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), phospho-GSK3β, GSK3β, GR, SOD1, CAT, NOX4, and β-actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

2.2. Cell culture

3T3-L1 preadipocyte were cultured in DMEM medium containing 3.7 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 1% P/S, and 10% BCS at 37°C in 5% CO2. Two-day postconfluent cells were induced to differentiate via treatment with 10% FBS and MDI hormone cocktail (0.5mM IBMX, 1.0μM DEX, and 5 μg/mL insulin; Day 0). The medium was replaced with DMEM containing 5 μg/mL insulin and 10% FBS for a further 2 d (Day 2). This medium was then replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS every other day until the indicated time point (Days 6–8). Next, 25μM, 50 μM, and 100μM Rg1 and 5mM NAC were dissolved in DMSO. The final concentration of DMSO was 0.25% in all experiments.

2.3. Cell viability assay

3T3-L1 preadipocyte (1 × 104 cells/well) in 96-well plates were treated with Rg1 (0μM, 25μM, 50μM, 100μM, and 200μM) and incubated for 24 h. XTT reagent and PMS were added to the culture and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Soluble formazan salt in the medium was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader Wallac 140 victor (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA, USA) at 450 nm against 690 nm.

2.4. Oil Red O staining

Differentiated 3T3-L1 cells, which were washed with PBS, were fixed with 10% formaldehyde at 4°C for 1 h. After washing with PBS, the fixed cells were stained with 0.5% Oil Red O in 60:40 (v/v) Oil Red O/H2O for 2 h at room temperature, and then washed three times with water. Lipid accumulation was observed with an inverted light Olympus CKX41 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Then, 100% isopropanol was used to elute Oil Red O dye, and the absorbance at 490 nm was determined using ELISA reader Wallac 140 victor (Perkin-Elmer).

2.5. NBT assay

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were grown to confluence and induced to differentiate into adipocytes, as previously described. Production of ROS was detected via an NBT assay. Nitrobluetetrazolium is reduced by ROS to a dark blue, insoluble form of NBT called formazan [11]. On Day 8 after induction, the cells were incubated for 90 min in PBS containing 0.2% NBT. Formazan was dissolved in 100% acetic acid, and the absorbance was determined using the ELISA reader Wallac 140 victor (Perkin-Elmer) at 570 nm.

2.6. Measurement of intracellular ROS production

3T3-L1 preadipocyte (1 × 104 cells/well) in 96-well plates were differentiated for 24 h. Differentiated cells were detected by 20μM DCF-DA. After incubation for 30 min in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C, 3T3-L1 cells were washed with PBS, and absorbance was determined by ELISA reader Wallac 140 victor (Perkin-Elmer) at 480 nm against 530 nm.

2.7. Western blotting

Cells were harvested by lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail II, III. Protein extracts (25 μg) were separated via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk and immunoblotted with primary antibodies specific for indicated proteins for overnight. Secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:5,000) were applied for 4 h. The bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence, and proteins were detected with LAS image software (Fuji, New York, NY, USA).

2.8. Animal husbandry

Wild-type adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) were initially obtained from Chungnam National University (Daejeon, South Korea). Embryos and larvae were obtained by natural mating and raised in embryo water containing Sea salts (Sigma) of 60 μg/mL until 5 d postfertilization (5 dpf). Then, larvae were maintained in 100-mm plate at a density of about 20 larvae per 100 mL, and fed hard-boiled egg yolk as an HFD once a day in the presence or absence of indicated compounds for 12–15 d (17–20 dpf). Zebrafish larvae used for imaging analysis were starved for 24 h to empty the digestive tract prior to Nile red staining.

2.9. Nile red staining, fluorescence imaging

The stock solution (1.25 mg/mL) of Nile red (Invitrogen N-1142) was prepared in acetone and stored in the dark at −20°C. For staining of fish, stock solution was diluted to 50 ng/mL in egg water and incubated for 5–10 min at 28°C in the dark. Fishes were washed with distilled water three times and anesthetized with a few drops of tricaine stock solution (Sigma; 4 mg/mL, pH 7.0). Fishes were mounted in 3% methylcellulose, and Nile red staining was imaged under ECLIPSE E600 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) fluorescence microscope, which was used for green fluorescent imaging.

2.10. Quantification of triglycerides

Triglyceride was measured using a total triglyceride assay kit (Zen-Bio, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). Cells and zebrafish were washed with phosphate-buffered saline to remove residual medium, and the cells were lysed with lysis buffer. Triglyceride was digested with Reagent B for 2 h to release hydrolyzed glycerols into the buffer. Diluted hydrolysates were incubated with Reagent A containing peroxidase to produce quinoneimine dye, which shows an absorbance maximum in spectrophotometric detection at 540 nm.

2.11. Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean standard deviation values. All data were obtained at least in triplicate or hexaplicate experiments. Differences among multiple groups were determined using one-way analysis of variance followed by Duncan's multiple range test using the SAS 9.0 software (SAS Institute, NC, USA). A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Rg1 attenuates lipid accumulation via regulation of C/EBPα, PPARγ, and aP2 in 3T3-L1

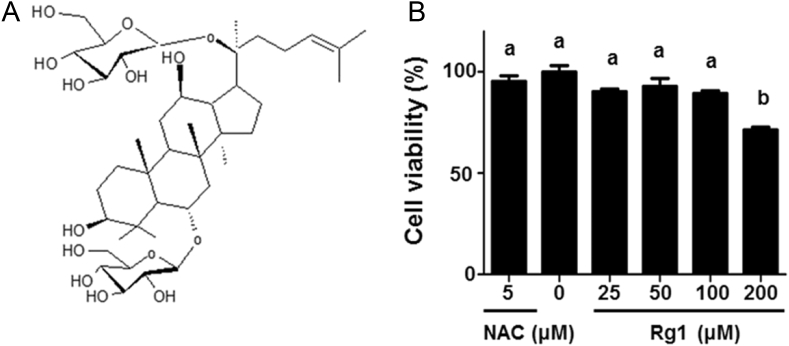

Ginsenoside Rg1 is an active component of ginseng as triterpenoid saponins, as shown in Fig. 1A. We performed the XTT assay to analyze the viability of 3T3-L1 cells treated with Rg1 for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 1B, Rg1 at 200μM in 3T3-L1 was found to be toxic to cells. Therefore, the concentrations of 25μM, 50μM, and 100μM Rg1 were selected for further investigation. Moreover, we measured the cytotoxicity of NAC, which has been used as an inhibitor of adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1. The concentration of 5μM NAC was not found to be toxic to cells compared with control.

Fig. 1.

Structure of Rg1 and its cytotoxicity in 3T3-L1 preadipocyte. (A) Chemical structure of Rg1 (C42H72O14). (B) 3T3-L1 preadipocyte were treated with 0μM, 25μM, 50μM, 100μM, and 200μM Rg1, and 5μM NAC for 24 h. Cell viability was measured by XTT assay at 450 nm and 690 nm. The experiment was performed in hexaplicates. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05. ANOVA, analysis of variance; NAC, N-acetyl cystein; XTT, 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carbox-anilide.

We investigated the effects of Rg1 on lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells. Rg1 decreased lipid accumulation in a dose-dependent manner during differentiation, as shown in Fig. 2A. Notably, the concentration of 100μM Rg1 showed a great reduction effect on lipid accumulation (more than 70%) compared with control. NAC, used as a positive control, strongly decreases lipid accumulation. Consistently, Rg1 suppressed adipogenesis-related key factors including C/EBPα, PPARγ, and aP2 in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Fig. 2B and Figs. S1A–S1C.

Fig. 2.

Rg1 downregulates adipogenic factors and triglyceride synthetic enzymes during adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. (A) Lipid accumulation was measured with Oil Red O assay in 3T3-L1 cells differentiated with the presence or absence of 25μM, 50μM, 100μM Rg1/5μM NAC during 8 d and determined at 490 nm. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test. The experiment was performed in hexaplicates. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05. (B) Cell lysates differentiated during 8 d were subjected to Western blot to analyze C/EBPα, PPARγ, and aP2 protein expression. The experiment was performed in triplicate. (C) Cell lysates differentiated during 8 d were subjected to Western blot to analyze LPAT, Lipin1, and DGAT1 protein expression. The experiment was performed in triplicate. ANOVA, analysis of variance; C/EBPα, CAAT/enhancer binding protein α; CON, control; NAC, N-acetyl cystein; ND, nondifferentiated preadipocyte; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ.

3.2. Rg1 downregulates triglyceride synthesis enzymes during differentiation in 3T3-L1

Lipid droplet in adipose tissue is mainly composed of triglycerides and sterol esters. A lack of triglyceride synthesis is known to block adipocyte differentiation [27]. The key enzymes for lipogenesis including LPAT, Lipin1, and DGAT1 catalyze triglyceride synthesis in adipose tissue [28], [29], [30].

To gain a better understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying the inhibition of triglyceride effect of Rg1, we used Western blotting to analyze the protein expression of LPAT, Lipin1, and DGAT1. Consistent with the increase in the adipogenic differentiation markers, the expression of key enzymes in triglyceride synthesis including LPAT, Lipin1, and DGAT increased substantially in control, as shown in Fig. 2C and Figs. S1D–S1F. By contrast, Rg1 dramatically derepressed the expression of LPAT, Lipin1, and DGAT1 in a dose-dependent manner compared to values in the cell without Rg1 treatment.

In particular, Lipin1 induces the expression of PPARγ via direct physical interaction and leads to elevated aP2 expression in the late stage of adipocyte differentiation [7], [31]. These lines of evidence prompted us to hypothesize that Rg1 may be a powerful reducer of adipogenesis at the early stage of adipocyte differentiation.

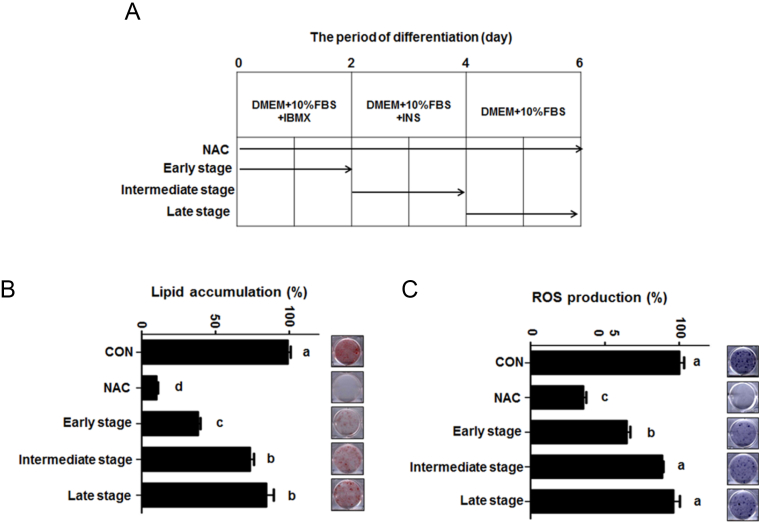

3.3. Rg1 preferentially suppresses lipid accumulation and ROS production in early stage of adipogenesis

Next, to test our hypothesis, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were stimulated to differentiation with MDI in the presence or absence of Rg1 in the early stage (Days 0–2), intermediate stage (Days 2–4), and later stage (Days 4–6) of adipocyte differentiation, as shown in Fig. 3A. We found that Rg1 decreased the differentiation from preadipocyte into adipocyte in a stage-dependent manner, as shown in Fig. 3B. Compared with cells treated with 100μM Rg1 in the intermediate stage (Days 2–4) and later stage (Days 4–6) of adipocyte differentiation, the optical density (OD) values of Oil Red O in the cells treated with 100μM Rg1 in the early stage (Days 0–2) of adipocyte differentiation significantly decreased by approximately 35.3% and 46.3%, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Rg1 preferentially suppresses lipid accumulation and ROS production at an early stage of adipogenesis. (A) Preadipocyte differentiation was initiated by IBMX, dexamethasone, and insulin in the presence or absence of 5mM NAC or 100μM Rg1 for the indicated tables. (B) Lipid accumulation was evaluated by Oil Red O assay in 3T3-L1 cells differentiated in the presence or absence of 5mM NAC/100μM Rg1 for the indicated tables and determined at 490 nm. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test. These data were measured as the standard deviation of hexaplicates. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05. (C) ROS production was subjected to NBT assay in cells differentiated during 6 d for the indicated tables and determined at 570 nm. Results were analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test. The experiment was performed in hexaplicates. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CON, control; IBMX, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine; NAC, N-acetyl cystein; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Moreover, the product of ROS is required to initiate preadipocyte differentiation into adipocyte [32]. Again, to determine whether Rg1 modulates early stage-specific adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1, the generation of intracellular ROS was measured using the NBT assay. Consistent with the decrease in intracellular lipid accumulation, Rg1 at 100μM significantly decreased ROS production in the early stage (Days 0–2) of adipocyte differentiation compared to cells treated with 100μM Rg1 in the intermediate stage (Days 2–4) and later stage (Days 4–6) of adipocyte differentiation, as shown in Fig. 3C.

To assess the changes in the activity of ROS-related antioxidant enzymes at an early stage of adipogenesis with MDI in the absence or presence of 25μM, 50μM, and 100μM Rg1, the expression of GPx, GR, SOD1, CAT, and NOX4 was determined as an indicator of ROS by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 4B and Figs. S2A–S2E, Rg1 was associated with a significant enhancer of the activities of the protective endogenous enzymes GPx, GR, and SOD1 at an early stage of adipogenesis, even at the lowest dose. The measured protein expression in the cells with the presence of 25μM, 50μM, and 100 μM Rg1 significantly increased by 37.2%, 42.9%, and 72.3% for GPx, and 62.9%, 73.1%, and 99.3% for GR, and 35.9%, 53.2%, and 75.6% for SOD1, respectively. Notably, CAT activity was increased in a dose-dependent manner. Loss of NOX4 suppresses ROS generation and insulin-induced terminal differentiation to adipocytes [33], [34]. Furthermore, we observed that Rg1 consistently decreased the significant expression of NOX4 protein compared with control.

Fig. 4.

Rg1 regulates antioxidant enzymes during early adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. (A) ROS production was detected by DCF-DA in cells differentiated in the treatment of 5mM NAC and 25μM, 50μM, and 100μM Rg1 during 24 h and determined at 480 nm against 530 nm. Results were analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test. The experiment was performed in hexaplicates. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05. (B) Cell lysates differentiated during 24 h were subjected to Western blot to analyze antioxidant enzymes and NOX4 protein expression. The experiment was performed in triplicate. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CON, control; DCF-DA, 2,7′-dichlorodihydrofluoresceindiacetate; NAC, N-acetyl cystein; ND, nondifferentiated preadipocyte; NOX 4, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen oxidase 4; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

These results indicate that Rg1 preferentially repressed the initiation of adipocyte differentiation via upregulation of endogenous antioxidant enzyme and downregulation of ROS-generating enzyme NOX4 during the early stage of adipogenesis.

3.4. Effects of Rg1 on early adipogenic factor by regulating antioxidant enzymes during early adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells

To gain a better understanding of the molecular mechanism uderlying the Rg1 effect at an early stage of adipocyte differentiation, we performed Western blotting to analyze the protein expression of C/EPBβ and CHOP10 in the early stage of adipogenesis (Day 2). As shown in Fig. 5A and Figs. S3A, S3B, the expression of C/EPBβ at an early stage of adipocyte differentiation with the absence of Rg1 was increased compared to that of the undifferentiated cells. By contrast, the cells treated with Rg1 showed a significant decrease in protein levels of C/EPBβ at an early stage of adipocyte adipogenesis in a dose-dependent manner. CHOP10 binds to C/EPBβ, preventing it from DNA regulatory sequence to regulate transcription. The expression of CHOP10 was downregulated in the early stage of adipocyte differentiation. Meanwhile, cells treated with Rg1 in the early stage of adipocyte differentiation dramatically attenuated the expression of CHOP10 protein in a dose-dependent manner.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Rg1 on early adipogenic factor by regulating antioxidant enzymes during early adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. (A) Cell lysates differentiated during 24 h were subjected to Western blot to analyze C/EBPβ and CHOP10 protein expression. The experiment was performed in triplicate. (B) Cell lysates differentiated during 24 h were subjected to Western blot to analyze GSK3β, ERK1/2, and p38 MAPK protein expression. The experiment was performed in triplicate. CHOP10, C/EBP homologous protein-10; CON, control; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; ND, nondifferentiated preadipocyte.

Furthermore, C/EPBβ is activated by phosphorylation of MAPK and GSK3β at the beginning of the S phase concurrent with the translocation of GSK3β from cytosol into the nucleus in the later stage of adipocyte differentiation [35]. To further elucidate the molecular mechanism of the inhibitory effect of Rg1 at the early stage of adipogenesis, we investigated the possibility of Rg1 acting as a MAPK and GSK3β suppressor. We observed that Rg1 derepressed phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and GSK3β compared with control in a dose-dependent manner, but not JNK1/2 and p38 MAPK repression by Rg1 in the early stage of adipocyte differentiation as shown in Fig. 5B and Figs. S3C–S3E.

These analysis data clearly indicated that Rg1 suppresses the early stage of gene expression cascade including CHOP10, ERK1/2, and GSK3β, and sequentially impaired adipocyte differentiation.

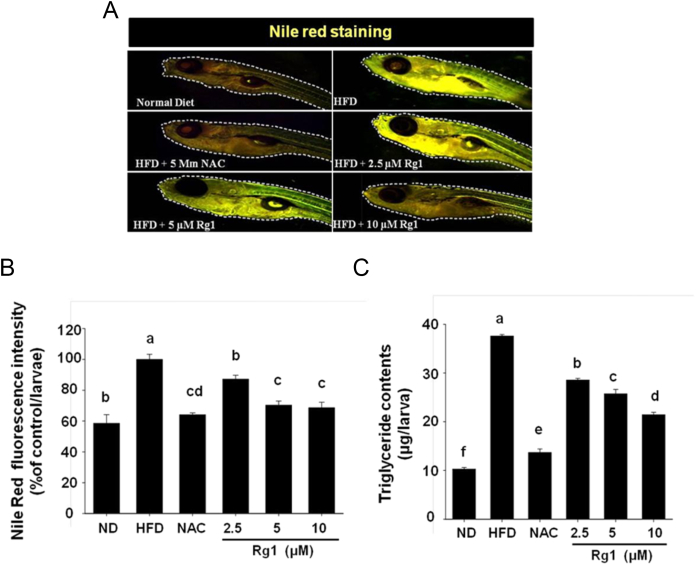

3.5. Rg1 supplement impair lipid accumulation in HFD-induced obese zebrafish

The afore-mentioned findings suggested that Rg1 disturbed the lipid accumulation via regulation of the early stage of adipocyte differentiation suppressor CHOP10 and adipogenesis cues in 3T3-L1. To finalize the analysis of the effect of Rg1 on lipid accumulation in vivo, we used HFD-induced obese zebrafish that possess structural and functional similarities with obese humans. As shown in Fig. 6A–C, significant increases in the fat mass and the content of triglyceride, which was quantified by driving the fluorescent intensity of Nile red staining or triglyceride measurement assay, were evident in the diet-induced obesity (DIO) zebrafish group compared with those in the nonfat diet control (NFD) group. By contrast, DIO zebrafish treated with Rg1 showed suppressed body fat accumulation in a dose-dependent manner. Consistent with this, the level of triglycerides was also inhibited when the DIO group was treated with Rg1. Hence, these results indicate that dietary Rg1 is beneficial for suppression of fat accumulation in the HFD-induced obese zebrafish model.

Fig. 6.

Rg1 supplementation impairs lipid accumulation in high fat diet-induced obese Zebrafish. (A) Lipid accumulation was evaluated by Nile Red staining in zebrafishes grown with HFD in the presence or absence of 5μM, 10μM, 2.5μM Rg1/5μM NAC during 20 dpf and visualized under a fluorescence microscope (n = 3). (B) Quantification of Nile Red fluorescence intensity. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test. The experiment was performed in triplicate. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05. (C) Triglyceride was subjected to TG assay in 20 dpf zebrafishes grown with HFD in the presence or absence of 5μM, 10μM, 2.5μM Rg1/5μM NAC, and measured at 540 nm. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test. The experiment was performed in triplicate. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CON, control; dpf, days postfertilization; NAC, N-acetyl cystein; HFD, high fat diet; ND, nondifferentiated preadipocyte; TG, triglyceride.

4. Discussion

In this study, we conducted two independent experiments to determine whether Rg1 suppresses adipocyte differentiation in the development of 3T3-L1 in a stage-dependent manner and fat accumulation in HFD-induced obese zebrafish.

C/EPBβ, a transcriptional factor of the C/EBPα, is expressed at the early stage of adipocyte differentiation [36] and is released by CHOP10 as it undergoes downregulation in the early stage of adipocyte differentiation [37]. We observed that the presence of Rg1 attenuates early-stage-specific adipocyte differentiation via the activation of CHOP10, which systemically suppresses adipogenesis cues such as C/EBPα and PPARγ and stimulates the expression of fatty acid synthase, which is essential for generating triglyceride droplets [38], [39]. We noted that fatty acid synthesis enzymes including LPAT, Lipin1, and DGAT1 were decreased in early-stage differentiation of 3T3-L1 treated with Rg1 compared with control. Attenuation of both adipogenic markers and fatty acid synthase can result in the suppression of lipid accumulation and ROS production, which were determined using Oil Red O staining and the NBT assay, during the early stage of differentiation of 3T3-L1 with the presence of Rg1 compared to the intermediate and later stages of differentiation of 3T3-L1 with the presence of Rg1. The DCF-DA assay has also revealed that Rg1 inhibited the accumulation of intracellular ROS production in a dose-dependent manner during the early stage of differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes.

ROS-associated endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as SODs, SOD1, and CAT convert O2– into H2O2 to prevent cytotoxicity by ROS production. In particular, their primary mechanism to eliminate H2O2 and lipid peroxides in the cytosol and mitochondria is catalyzed by GPx, which uses glutathione to reduce H2O2 and hydroperoxides into water and alcohols, respectively [40], [41]. We observed that GPx, GR, SOD1, and CAT were consistently increased in a dose-dependent manner during the early stage of differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes with the presence of Rg1.

The production of ROS is released via the balance of antioxidant and pro-oxidant enzymes. NOX4 acts as a pro-oxidant enzyme that produces ROS levels and plays a crucial role of the electron donor for NADPH [42]. We observed that the presence of Rg1 significantly decreased the gene expression of endogenous pro-oxidant enzyme NOX4 during early-stage differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes.

The MAPK signaling pathway is ubiquitously expressed, highly conserved GSK3β, and involved in adipocyte differentiation [43]. ERK is one of the MAPKs that have been suggested to play a role in the development of insulin resistance and obesity [44]. We observed that Rg1 inhibited the phosphorylation of GSK3β and ERK stimulated during early-stage differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes in a dose-dependent manner compared to control, but not the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK.

The aforementioned evidence suggested that Rg1 attenuated lipid accumulation via regulation of early-stage adipogenic markers and its downstream target molecules. These results indicate that Rg1 can repress fat accumulation in vivo. To examine whether Rg1 attenuates body fat accumulation, we used the HFD-induced zebrafish model. We observed that in HFD-induced obese zebrafish, levels of fluorescence intensity were increased, whereas the HFD-fed and Rg1-treated group showed significant levels of decrease in fluorescence intensity in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, the HFD-fed and Rg1-treated group showed reduced triglyceride content by approximately 60% compared with control to HFD without Rg1 treatment group. These results indicate that Rg1 decreased the accumulation of lipids and triglycerides in HFD-induced obese zebrafish.

In conclusion, the current data demonstrate that Rg1 increases CHOP10 during the early stage of differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes, which might disrupt the multiple downstream of adipogenic cascades and subsequently attenuate lipid accumulation in vitro and in vivo. Hence, we suggest that Rg1 might have the potential to beneficially suppress body fat accumulation in the early stage obesity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2016R1D1A1A09917209). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2015.12.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Wahba I.M., Mak R.H. Obesity and obesity-initiated metabolic syndrome: mechanistic links to chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:550–562. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04071206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guilherme A., Virbasius J.V., Puri V., Czech M.P. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:367–377. doi: 10.1038/nrm2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornelius P., MacDougald O.A., Lane M.D. Regulation of adipocyte development. Annu Rev Nutr. 1994;14:99–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.000531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDougald O.A., Lane M.D. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression during adipocyte differentiation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:345–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandrup S., Lane M.D. Regulating adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5367–5370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soukas A., Socci N.D., Saatkamp B.D., Novelli S., Friedman J.M. Distinct transcriptional profiles of adipogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34167–34174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh Y.K., Lee M.Y., Kim J.W., Kim M., Moon J.S., Lee Y.J., Ahn Y.H., Kim K.S. Lipin1 is a key factor for the maturation and maintenance of adipocytes in the regulatory network with CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34896–34906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnefont-Rousselot D. Obesity and oxidative stress: potential roles of melatonin as antioxidant and metabolic regulator. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2014;14:159–168. doi: 10.2174/1871530314666140604151452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu G.S., Chan E.C., Higuchi M., Dusting G.J., Jiang F. Redox mechanisms in regulation of adipocyte differentiation: beyond a general stress response. Cells. 2012;1:976–993. doi: 10.3390/cells1040976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksson J.W. Metabolic stress in insulin's target cells leads to ROS accumulation — a hypothetical common pathway causing insulin resistance. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3734–3742. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furukawa S., Fujita T., Shimabukuro M., Iwaki M., Yamada Y., Nakajima Y., Nakayama O., Makishima M., Matsuda M., Shinomura J. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H., Lee Y.J., Choi H., Ko E.H., Kim J.W. Reactive oxygen species facilitate adipocyte differentiation by accelerating mitotic clonal expansion. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10601–10609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808742200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darlington G.J., Ross S.E., MacDougald O.A. The role of C/EBP genes in adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30057–30060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearson G., Robinson F., Beers Gibson T., Xu B.E., Karandikar M., Berman K., Cobb M.H. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bost F., Aouadi M., Caron L., Binetruy B. The role of MAPKs in adipocyte differentiation and obesity. Biochimie. 2005;87:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prusty D., Park B.H., Davis K.E., Farmer S.R. Activation of MEK/ERK signaling promotes adipogenesis by enhancing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) and C/EBPalpha gene expression during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46226–46232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park B.H., Qiang L., Farmer S.R. Phosphorylation of C/EBPbeta at a consensus extracellular signal-regulated kinase/glycogen synthase kinase 3 site is required for the induction of adiponectin gene expression during the differentiation of mouse fibroblasts into adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8671–8680. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8671-8680.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glade M.J. Food, nutrition, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. American Institute for Cancer Research/World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research, 1997. Nutrition. 1999;15:523–526. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt B.M., Ribnicky D.M., Lipsky P.E., Raskin I. Revisiting the ancient concept of botanical therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:360–366. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0707-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kris-Etherton P.M., Hecker K.D., Bonanome A., Coval S.M., Binkoski A.E., Hilpert K.F., Griel A.E., Etherton T.D. Bioactive compounds in foods: their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am J Med. 2002;113:71S–88S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00995-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia L., Zhao Y. Current evaluation of the millennium phytomedicine—ginseng (I): etymology, pharmacognosy, phytochemistry, market and regulations. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:2475–2484. doi: 10.2174/092986709788682146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attele A.S., Wu J.A., Yuan C.S. Ginseng pharmacology: multiple constituents and multiple actions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang C.R., Lee S.H., Jang G.Y., Hwang I.G., Kim H.Y., Woo K.S., Lee J., Jeong H.S. Changes in ginsenoside compositions and antioxidant activities of hydroponic-cultured ginseng roots and leaves with heating temperature. J Ginseng Res. 2014;38:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee H.M., Lee O.H., Kim K.J., Lee B.Y. Ginsenoside Rg1 promotes glucose uptake through activated AMPK pathway in insulin-resistant muscle cells. Phytother Res. 2012;26:1017–1022. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu S.H., Huang H.Y., Korivi M., Hsu M.F., Huang C.Y., Hou C.W., Chen C.Y., Kao C.L., Lee R.P., Kuo C.H. Oral Rg1 supplementation strengthens antioxidant defense system against exercise-induced oxidative stress in rat skeletal muscles. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2012;9:23. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park S., Ahn I.S., Kwon D.Y., Ko B.S., Jun W.K. Ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1 suppress triglyceride accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and enhance beta-cell insulin secretion and viability in Min6 cells via PKA-dependent pathways. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:2815–2823. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gale S.E., Frolov A., Han X., Bickel P.E., Cao L., Bowcock A., Schaffer J.E., Ory D.S. A regulatory role for 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate-O-acyltransferase 2 in adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11082–11089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishimura S., Manabe I., Nagasaki M., Eto K., Yamashita H., Ohsugi M., Otsu M., Hara K., Ueki K., Sugiura S. CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Nat Med. 2009;15:914–920. doi: 10.1038/nm.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sethi J.K., Hotamisligil G.S. The role of TNF alpha in adipocyte metabolism. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1999;10:19–29. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H.C., Smith S.J., Tow B., Elias P.M., Farese R.V., Jr. Leptin modulates the effects of acyl CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase deficiency on murine fur and sebaceous glands. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:175–181. doi: 10.1172/JCI13880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim H.E., Bae E., Jeong D.Y., Kim M.J., Jin W.J., Park S.W., Han G.S., Carman G.M., Koh E., Kim K.S. Lipin1 regulates PPARgamma transcriptional activity. Biochem J. 2013;453:49–60. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tormos K.V., Anso E., Hamanaka R.B., Eisenbart J., Joseph J., Kalyanaraman B., Chandel N.S. Mitochondrial complex III ROS regulate adipocyte differentiation. Cell Metab. 2011;14:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mouche S., Mkaddem S.B., Wang W., Katic M., Tseng Y.H., Carnesecchi S., Steger K., Meier C.A., Foti M., Muzzin P. Reduced expression of the NADPH oxidase NOX4 is a hallmark of adipocyte differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1015–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanda Y., Hinata T., Kang S.W., Watanabe Y. Reactive oxygen species mediate adipocyte differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells. Life Sci. 2011;89:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X., Kim J.W., Gronborg M., Urlaub H., Lane M.D., Tang Q.Q. Role of cdk2 in the sequential phosphorylation/activation of C/EBPbeta during adipocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11597–11602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703771104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang Q.Q., Lane M.D. Activation and centromeric localization of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins during the mitotic clonal expansion of adipocyte differentiation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2231–2241. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang Q.Q., Lane M.D. Role of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP-10) in the programmed activation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-beta during adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12446–12450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220425597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowe C.E., O'Rahilly S., Rochford J.J. Adipogenesis at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2681–2686. doi: 10.1242/jcs.079699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poulos S.P., Dodson M.V., Hausman G.J. Cell line models for differentiation: preadipocytes and adipocytes. Exp Biol Med. 2010;235:1185–1193. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu T., Nojiri H., Kawakami S., Uchiyama S., Shirasawa T. Model mice for tissue-specific deletion of the manganese superoxide dismutase gene. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2010;10:S70–S79. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fransen M., Nordgren M., Wang B., Apanasets O. Role of peroxisomes in ROS/RNS-metabolism: implications for human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:1363–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bedard K., Krause K.H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kyriakis J.M., Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirosumi J., Tuncman G., Chang L., Gorgun C.Z., Uysal K.T., Maeda K., Karin M., Hotamisligil G.S. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature. 2002;420:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.