Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, highly conserved non-coding RNAs that play important roles in the regulation of many physiological processes. However, the role of miRNAs in vertebrate oocyte formation (i.e., oogenesis) remains poorly investigated. To gain new insights into the roles of miRNAs in oogenesis, we searched for ovarian-predominant miRNAs. Using a microarray displaying 3,800 distinct miRNAs originating from different vertebrate species, we identified 66 miRNAs that are expressed predominantly in the ovary. Of the miRNAs exhibiting the highest overabundance in the ovary, 20 were selected for further analysis. Using a combination of QPCR and in silico analyses, we identified 8 novel miRNAs that are predominantly expressed in the ovary, including 2 miRNAs (miR-4785 and miR-6352) that exhibit strict ovarian expression. Of these 8 miRNAs, 7 were previously uncharacterized in fish. The strict ovarian expression of miR-4785 and miR-6352 suggests an important role in oogenesis and/or early development, possibly involving a maternal effect. Together, these results indicate that, similar to protein-coding genes, a significant number of ovarian-predominant miRNA genes are found in fish.

Oogenesis and early embryogenesis are highly regulated and coordinated biological processes requiring a large network of gene interactions and tightly regulated genes. During oogenesis, maternal transcripts and proteins are produced and accumulated in oocytes to prepare for meiosis resumption and early embryo development1. Genes that exhibit an oocyte-predominant expression pattern have important functions during oogenesis and early embryogenesis2,3,4. These genes are also called oocyte-specific genes2.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs (19–24 nt) that modulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by repressing mRNA translation or by regulating mRNA degradation. Most miRNAs are evolutionarily conserved and play important roles in many physiological and pathological processes5,6,7. The contribution of miRNAs to oogenesis and early embryo development was demonstrated in mice with the report of an arrest of zygotic development after the loss of specific maternal miRNAs and infertility in Dicer1-deficient females8,9. It was also shown that a specific miRNA, miR-430, is responsible for maternal mRNA clearance during the embryonic development of zebrafish10. Many studies have reviewed the critical roles played by miRNAs in controlling the expression of genes essential for folliculogenesis and early embryogenesis11,12,13,14. Significant efforts have been made to identify ovarian miRNAs using microarrays or high-throughput sequencing15,16,17,18,19. However, no comprehensive overview on the ovarian miRNome is available. Additionally, data on ovarian-predominant miRNAs and on the roles of individual miRNAs during oogenesis and early embryonic development remain scarce, especially in non-mammalian models. Based on the hypothesis that ovarian-predominant miRNA genes would also play important roles in oogenesis and/or in early development similar to protein-coding genes, we searched for ovarian-predominant miRNAs in medaka (Oryzias latipes). To this end, we designed a miRNA microarray displaying most of the vertebrate miRNAs available in miRBase. We used this microarray to analyze the expression of miRNAs in 10 different tissues. Here, we report the identification of 66 miRNAs that are significantly overabundant in the ovary in comparison to other tissues. Using a combination of QPCR and in silico analyses, we identified 8 miRNAs that are predominantly expressed in the ovary, including 2 miRNAs that exhibit strict ovarian expression. Of these 8 miRNAs, 7 were previously uncharacterized in fish. Together, these results indicate that a significant number of ovarian-predominant miRNA genes are found in fish, similarly to protein-coding genes. The strict ovarian expression of miR-4785 and miR-6352 suggests important roles in oogenesis or early development, possibly involving maternal effects. Our findings provide new insights into the participation of ovarian-specific miRNAs in oogenesis and/or early embryo development.

Results

Identification of novel ovarian-predominant miRNAs using microarray

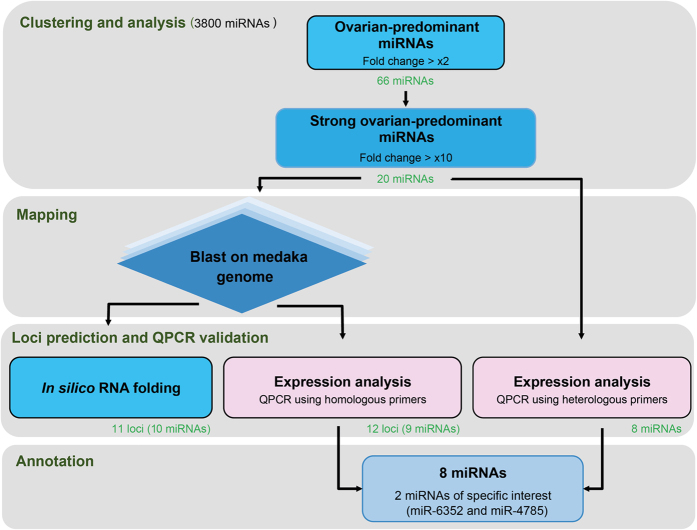

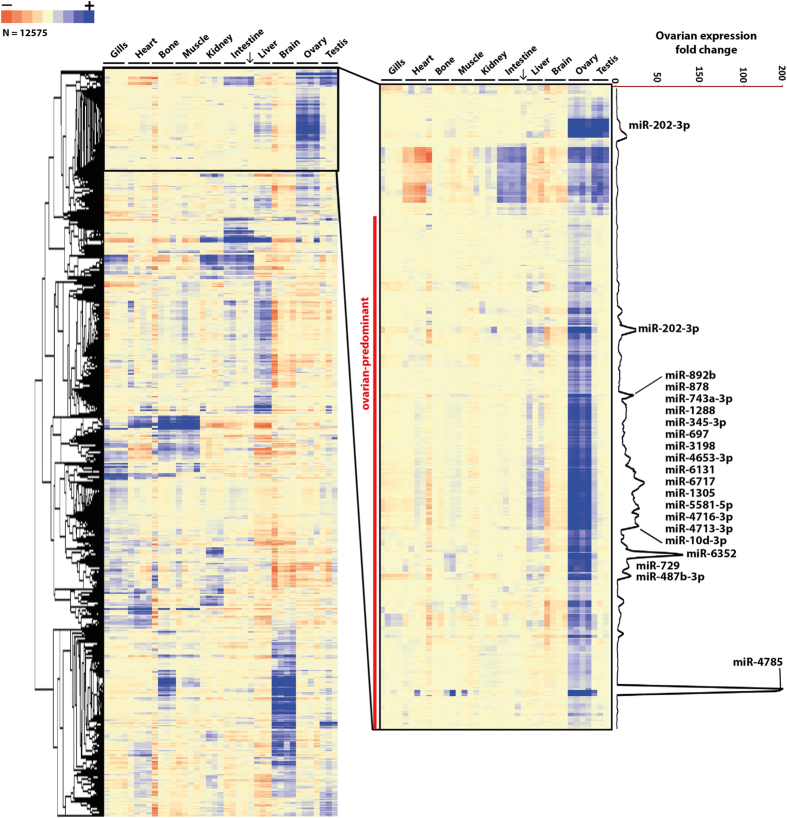

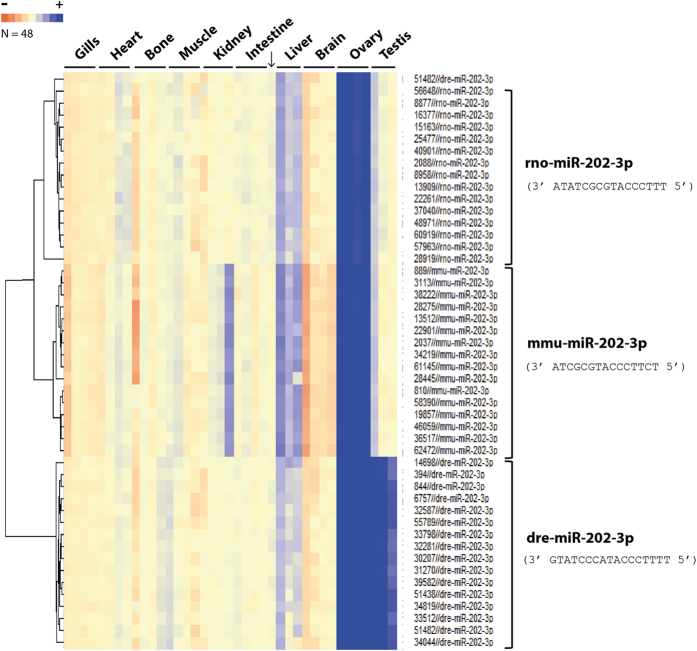

To identify ovarian-predominant miRNAs in medaka, we performed a miRNA microarray experiment using a generic microarray that displayed a large repertoire of vertebrate miRNA sequences as previously described20. The workflow applied to analyse the resulting dataset is described in Fig. 1. Of the 3800 miRNAs present on the microarray, 66 miRNAs (corresponding to 71 probes) exhibited a significant ovarian-predominant expression (>2-fold, p < 0.005, Fig. 2, Supplemental Fig. S1). Thirty-four of these miRNAs probes corresponded to human sequences, 16 to mice sequences, 14 to rat sequences, 4 to zebrafish sequences, 2 to chicken sequences and 1 to a medaka sequence. For further analysis, we selected 20 miRNAs displaying dramatic ovarian-predominant expression (>10-fold, p < 0.005). Of these 20 miRNAs was zebrafish miR-202-3p (dre-miR-202-3p), which we selected despite its detection in both the ovary and testis (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the microarray profiles displayed two other probes (rno-miR-202-3p and mmu-miR-202-3p) that exhibited strict ovarian-predominance and suggested the presence of a miR-202 isomiR in medaka.

Figure 1. Workflow used to analyze the data and identify novel ovarian-predominant miRNAs in medaka.

Figure 2. MicroRNA expression profiling in different medaka tissues.

Unsupervised clustering analysis of the differentially expressed microRNAs. Each row represents a single probe (16 probes per miRNA) and each column represents a tissue sample (gills, heart, bone, muscle, kidney, intestine, liver, brain, ovary and testis). Data were median-centered prior to the clustering analysis. For each miRNA probe, the expression level within the sample set is indicated using a color density scale. Blue and red are used for overexpression and underexpression, respectively. White is used for median expression. The arrow indicates a testis sample that clusters with the intestine samples, which is probably due to tissue contamination during sampling.

Figure 3. Expression profiles of miR-202-3p in different medaka tissues.

Each row represents a single probe (16 probes per miRNA). Each column represents a medaka tissue RNA sample. The zebrafish probes (dre-miR-202-3p) display gonadal-predominant expression profiles, whereas probes from rat and mouse (rno-miR-202-3p and mmu-miR-202-3p, respectively) exhibited strict ovarian-predominant expression profiles. Probe sequences are indicated.

Further QPCR validation of the most ovarian-predominant miRNAs

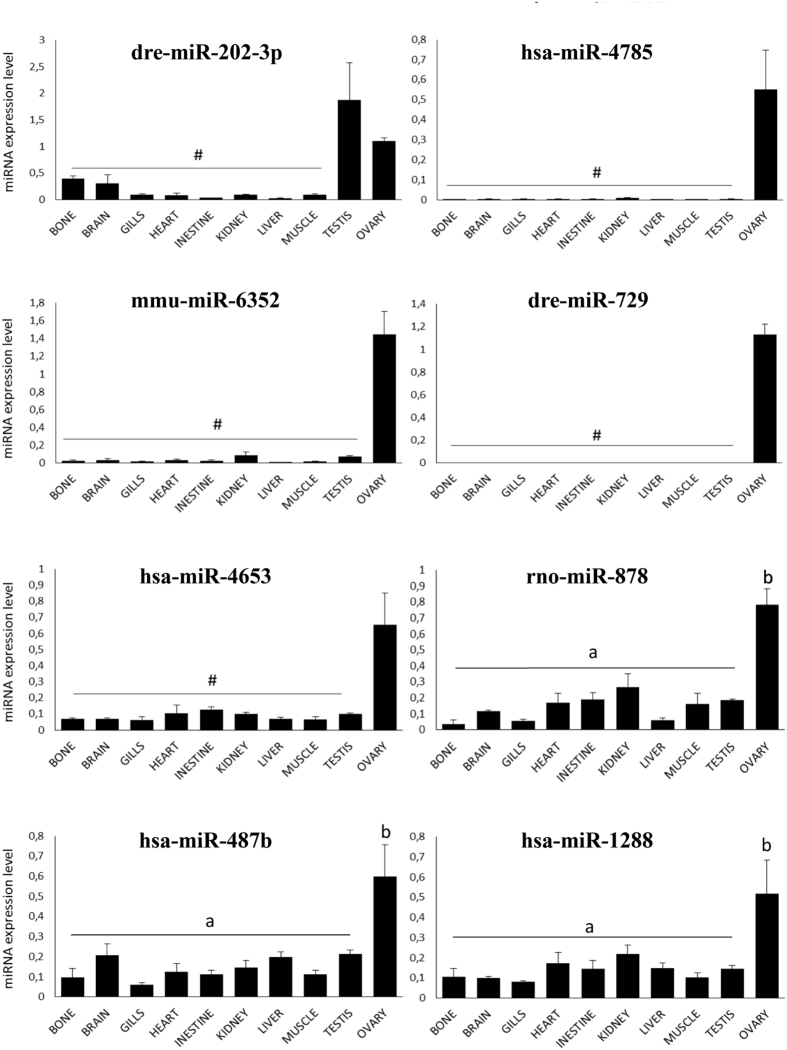

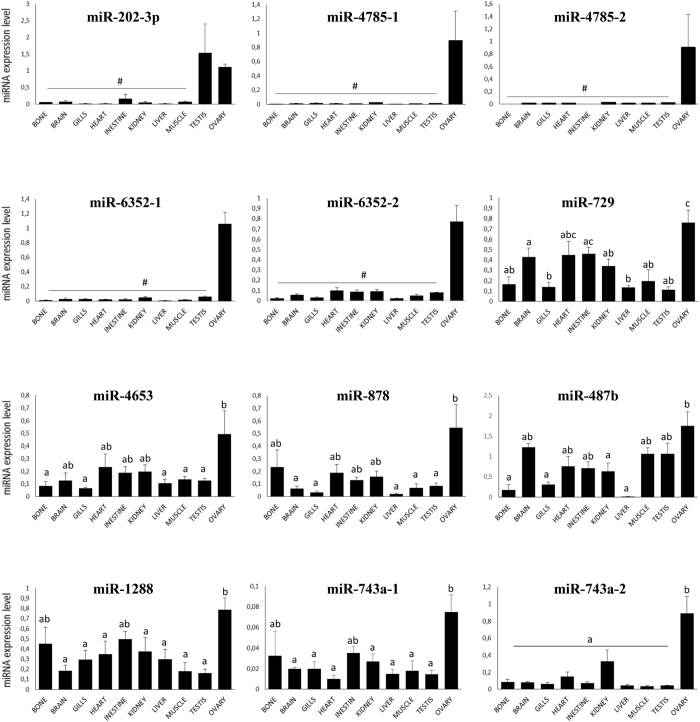

For the 20 ovarian-predominant miRNAs, tissue expression was analyzed by QPCR and compared to the profiles obtained in the microarray study. The expression profiles were generated using primers corresponding to heterologous miRNAs (i.e., heterologous primers) originating from various vertebrate species and according to the sequences present on the microarray (Supplemental Fig. S2). In the QPCR analysis, 7 candidates exhibited an ovarian-predominant expression profile that was consistent with the microarray data (hsa-miR-4785, mmu-miR-6352, dre-miR-729, hsa-miR-4653, rno-miR-878, hsa-miR-487b and hsa-miR-1288); excepted dre-miR-729, these miRNAs were previously uncharacterized in fish (Fig. 4). The ovarian-predominant expression was especially strict for hsa-miR-4785, mmu-miR-6352, dre-miR-729 and hsa-miR-4653. It was less pronounced though still significant for rno-miR-878, hsa-miR-487b and hsa-miR-1288. The expression profile of dre-miR-202-3p revealed a strong and significant overabundance in the testis and ovary compared to other tissues. In contrast, 3 of the 20 miRNAs (mmu-miR-743a-3p, hsa-miR-4713-3p and hsa-miR-4716-3p) were expressed in all tissues at different levels without any overexpression in the ovary. For the other 8 candidates (hsa-miR-5581-5p, hsa-miR-3198, hsa-miR-6131, hsa-miR-6717-5p, rno-miR-345-3p, mmu-miR-697, hsa-miR-892b and dre-miR-10d-3p), QPCR resulted in more than one product, which made it impossible to conclude on their overexpression in the ovary. Finally, we failed at amplifying hsa-miR-1305 by QPCR.

Figure 4. miRNA expression profiles obtained by QPCR using heterologous primers.

Four samples from different individual medaka fish were used for each tissue. Expression levels were measured in duplicates and the mean values (±SD) are displayed on the graphs. Data were normalized to the abundance of 18 S. a and b indicate expression levels that are significantly different (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.05). ab, expression levels not significantly different from a and b expression levels not significantly different from the background signal.

Identification of cognate medaka miRNA genes

To identify the cognate medaka miRNA sequences, we searched the medaka genome for miRNA genes that were orthologous to the miRNA sequences identified in the microarray analysis. For the 20 ovarian-predominant miRNAs candidates, corresponding sequences were aligned (BLAST) on the medaka genome. All 20 miRNAs had at least one match in the medaka genome with at least 90% identity over 86% of the query length. The best hits (from 2 to 4 depending on the candidate) were considered as potential loci for being the corresponding medaka miRNA gene(s) (Table 1). The surrounding genomic regions were used as templates to determine the potential whole precursor sequences and the secondary structures were computed for these sequences. In silico prediction of the hairpin structures supported the identification of 11 loci that encode for 10 miRNAs (Supplemental Fig. S3; Table 1). Among them, 3 are miRtrons (mir-6352, mir-1305 and mir-6717) that are present in the introns of ENSORLG00000017404, fam171a1 (family with sequence similarity 171, member A1) and shank1 (SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 1), respectively. One is in an exon in the protein-coding transcript of the rasip1 gene (ras interacting protein 1), while 9 are intergenic miRNAs.

Table 1. Characterization of a subset of novel medaka miRNAs predominantly expressed in the ovary.

| miRNA | QPCR heterologous | Locus | Sequence | Location | Folding | QPCR homologous | miRNA origins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-6352-5p | + | 1 | CAGGGAACAGGACCCCAGCT | 9:31095668–31095687 | + | + | miRtron/ENSORLG00000017404 |

| 2 | AACTGGGAAAAGGACCCCAG | 3:26171679–26171698 | − | + | miRtron/myo5aa | ||

| 3 | TTTGGGAAAAAGATCCCAGCT | 1:31427215–31427235 | − | − | NC | ||

| 4 | AAATGGGAAAAGCACCCCAG | 20:10904125–10904144 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-4785–3p | + | 1 | GAGTCTGCGTCGCCGCCAGC | 16:16874299–16874318 | + | + | miR/rasip |

| 2 | TGATCTCGGAGACGCCGCCAGC | scaffold983:45388–45409 | + | + | miR | ||

| 3 | CGAGTCGGCGATGCCGCCGCC | 9:761851–761871 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-878–3p | + | 1 | GCATGACAACATACTGGGTA | 12:12844102–12844121 | − | + | miR |

| 2 | GCATGAAACCATACTGGGTC | 13:25685522–25685541 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-1288-3p | + | 1 | TGGACTGTCCTGATGTGGAGA | 6:5567815–5567835 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | TGGACAGCCCTGATGTGGAG | 1:27438143–27438162 | + | + | miR | ||

| miR-4653-3p | + | 1 | GAGTTAAGGGTAGTTTGGAGA | 18:4398355–4398375 | − | + | miR |

| 2 | CTCTGTTAAGGGTTGCCTGGA | ultracontig49:380302–380322 | − | − | NC | ||

| 3 | AGAAAGTTGAGGGTTGCTTGG | 21:27820909–27820929 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-729–3p | + | 1 | CATGGGTATGAAACGACCCGGGT | 20:6728838–6728860 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | CATGGGTATGATACGACCTCA | scaffold1021:47363–47383 | + | + | miR | ||

| 3 | GGTATGATTCGGCCTGGGTT | 15:3091445–3091464 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-487b-3p | + | 1 | CGGCGTACAGGGTCATCCAC | 22:3962447–3962466 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | GTCCCCTACAAGGTCATCCACTT | 10:7430304–7430326 | − | + | miRtron/mrpl11 | ||

| miR-202-3p | + | AGAGGCATAAGGCATGGGAA | 15:1382691–1382710 | + | + | miR | |

| miR-743a-3p | − | 1 | GAAAGACGCCAAAGTGGGT | 2:28436804–28436822 | − | + | miR |

| 2 | GAAAGTCGCCAAACTGGGT | 18:15585090–15585108 | − | + | miR | ||

| miR-1305-3p | − | 1 | TTTTCAACTCTATTGGGAAA | 12:19213569–19213588 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | ATGTTCAACTCTAATGTGAGA | 24:18349479–18349499 | − | − | NC | ||

| 3 | TTTTCACCTCTAATGGGATAG | 16:14807294–14807314 | + | − | miRtron/fam171a1 | ||

| miR-4716-3p | − | CTGGGGGAAGCAAACATGGAGA | 7:23549695–23549716 | + | − | miR | |

| miR-6131-3p | − | 1 | CGCTGATCAGATGGGAGTCG | 15:2799945–2799964 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | ACTGGTGAGATGGGAGTGGC | 12:21774089–21774108 | + | − | miR | ||

| miR-10d-3p | − | TACCCTGTAGAACCGAATGTGT | 15:4353766–4353787 | + | − | miR | |

| miR-6717-5p | − | 1 | GGCGATGGGGGGATGCAGAGA | 19:8376541–8376561 | + | − | miRtron/shank1 |

| 2 | AAAGATGTGGGGATGTGGAGA | scaffold1101:27027–27047 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-345-3p | − | 1 | CCCTGAACTCGGGGTATGGA | 16:8875414–8875433 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | CTGAACTAGGGTTCAGGAGA | 16:14238722–14238741 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-697-3p | − | 1 | AGCATCCTGTTCCTGTGGAG | scaffold5397:869–888 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | ACATCCTGGACCTGTGGA | scaffold692:99305–99322 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-3198-3p | − | 1 | GTGGAGTCCTGAGGACTGGAG | 5:11964002–11964022 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | GTGGAGTCCTGCAGAATGGAG | 19:5590938–5590958 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-4713-3p | − | 1 | TGGGATCCAGACAGAGGGAGAA | 15:20189222–20189243 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | TGGGATGCAGAAAGTGGGAGAA | 17:30648359–30648380 | − | − | NC | ||

| 3 | AAAGATCCAGACAGTTGGAGA | scaffold693:106481–106501 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-5581-5p | − | 1 | AGCCTTCCAGGAAAAATGGAG | scaffold4519:2360–2380 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | AGCCTTCCAGGAAAAATGGACA | scaffold5870:432–453 | − | − | NC | ||

| miR-892b-3p | − | 1 | ACTGGGTCCTTTCTGTGTAGA | 3:12292877–12292897 | − | − | NC |

| 2 | CACTGGCTCTTTTCTGGGAA | 23:15587446–15587465 | − | − | NC |

Eight miRNAs displayed an ovarian-predominant expression profile when using heterologous and homologous QPCR primers. In addition, in silico folding predictions allowed characterizing 13 loci that encode 11 different miRNAs. +, successful QPCR or hairpin structure prediction. NC, not confirmed.

Expression profiles of the mature medaka miRNAs

For each medaka genomic locus predicted for the 20 candidate miRNAs, we analyzed the expression profile of the corresponding mature miRNAs to confirm the ovarian-predominant expression previously obtained by the microarray analysis or by heterologous QPCR. For each locus, the corresponding medaka primer (i.e., homologous primer) was designed for QPCR (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Fig. S4). MiR-202-3p exhibited a strong expression in both the ovary and testis compared with other tissues. Four loci exhibited strict ovarian-predominant expression of the mature sequences, including miR-4785-1, miR-4785-2, miR-6352-1 and miR-6352-2. Significant ovarian-predominant expression was also observed for miR-743a-2, even though it was detected in all tissues, especially the kidney. For the other loci (miR-729, miR-4653, miR-878, miR-487b, miR-1288 and miR-743a-1), overexpression in the ovary was not systematically significant when compared with other tissues. These 12 loci corresponded to 9 different miRNAs (Table 1). Three of them exhibited an ovarian–predominant expression profile (miR-4785, miR-6352 and miR-743a-2).

Figure 5. miRNAs expression profiles obtained by QPCR using medaka homologous primers.

Four samples from different medaka fish were used for each tissue. Expression levels were measured in duplicates and the mean values (±SD) are displayed on the graphs. Data were normalized to the abundance of 18S. a and b indicate expression levels that are significantly different (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.05). ab, expression levels not significantly different from a and b. #expression levels not significantly different from the background signal.

Target prediction

MiR-4785 and miR-6352 were strictly ovarian-predominant when analyzed by QPCR using homologous or heterologous primers. To identify cellular processes putatively targeted by these 2 miRNAs, target genes were predicted using TargetScan and Miranda (Supplemental Fig. S6). A total of 11 and 17 common genes were identified for miR-4785 and miR-6352, respectively. The expression profiles of some putative targets were also examined in medaka using the PhyloFish tissue repertoire database (http://phylofish.sigenae.org)21, with a special interest for genes expressed in ovary (Supplemental Fig. S6).

Discussion

Ovarian-predominant genes are known to play important roles in folliculogenesis, oocyte growth and maturation throughout oogenesis and in early embryo development22,23,24. While most studies have been conducted in mammals, studies in fish have shown that many oocyte-specific genes could also be found in fish25,26. Oocyte-specific features are typical of maternal-effect genes and play key roles in early embryonic development. For instance, Nucleoplasmin (Npm2) is a maternal-effect gene required for embryonic development beyond zygotic genome activation (ZGA) in both mice and zebrafish3,27. Along with other evidence, this suggests that oocyte-specific genes would be conserved in vertebrates both in terms of function and expression pattern (i.e., oocyte-specific expression). Therefore, our working hypothesis was that ovarian-predominant miRNA genes would also play important roles in oogenesis and early embryonic development in a similar manner to protein-coding genes. In the present study, we were able to identify 66 miRNAs exhibiting ovarian-predominant expression. Of the 66 ovarian-predominant miRNAs selected from the microarray data, 10 miRNAs (including mmu-miR-743a, rno-miR-878 and hsa-miR-487b) were previously identified in the mouse ovary or germline28. Two miRNAs (hhi-miR-145 and hhi-miR-202) were previously shown to be predominantly expressed in gonads compared with non-reproductive organs in vertebrates20,29,30,31. Finally, 54 miRNAs (including mmu-miR-6352, hsa-miR-4785, hsa-miR-1305, and hsa-miR-5581) had never been reported as ovarian-predominant miRNAs in any vertebrate species. The expression of some miRNAs observed here in a tissue-dependent manner is consistent with previous results obtained in rainbow trout32. Similarly, it was recently demonstrated in humans that the majority of miRNAs was neither specific to single tissues nor housekeeping miRNAs. Nonetheless, these investigators concluded that many different miRNAs and miRNA families were predominantly expressed in certain tissues33. To our knowledge, no study has ever specifically aimed at identifying ovarian-predominant miRNAs in non-mammalian vertebrates. Therefore, we report here, for the first time in any vertebrate species, more than 60 miRNAs that are significantly and predominantly expressed in the ovary. These results were obtained using a generic microarray displaying mature miRNA sequences originating from various vertebrate species. In general, microarray expression profiles can be confirmed by quantitative QPCR, as discrepancies between the two techniques are limited34; further, this methodology was previously used in rainbow trout. In our study, some miRNAs that exhibited ovarian expression profiles in the microarray study were detected in all tissues by QPCR. The presence of different isomiRs could explain, at least in part, these differences in the expression profiles. This is especially true if sequencing originally identified the miRNA sequence present on the microarray. Deep sequencing now allows the detection of variability in miRNA mature sequences, meaning that many different sequences can be generated and subsequently sequenced from the same miRNA precursor. Consistently, previous studies showed that isomiR expression patterns differ between cell lines and/or tissue types35,36. Sorting and identifying isomiRs remains a challenge in miRNA studies, as the sequence diversity of isomiRs can vary on both ends. This can be an issue for distinguishing mature isoforms from isomiR species37,38. More generally, being able to connect a murine or human miRNA gene to its corresponding medaka ortholog has limited our study, as is also the case for protein-coding genes39. Direct mapping of heterologous miRNA sequences on the medaka genome revealed that sequences could map on either one or several loci. In the present study, we identified 12 medaka miRNA genes that corresponded to 9 mature miRNAs. For instance, mmu-mir-6352, hsa-mir-4785 and mmu-mir-743a each have two co-orthologs in medaka (ola-mir-6352-1 and ola-mir-6352-2, ola-mir-4785-1 and ola-mir-4785-2, and ola-mir-743a-1 and ola-mir-743a-2, respectively) that could possibly result from the teleost genome duplication, while only one copy of ola-mir-202, ola-mir-487b, ola-mir-4653, ola-mir-878 and ola-mir-1288 appear to be present in the medaka genome40,41. We also identified another co-ortholog for ola-mir-729, even though we have been unable to detect it by QPCR. Because the identification of cognate medaka miRNAs is not always straightforward, we used a combination of evidence including sequence matches on the medaka genome, QPCR expression and miRNA folding prediction. The corresponding information is summarized in Table 1 for the 20 ovarian-predominant miRNAs selected. The folding information should be used with caution, as all miRNAs do not necessarily exhibit this feature42. Finally, it should be stressed that despite the overall conservation of the ovarian-predominant patterns, we observed some differences between the QPCR profiles obtained using homologous and heterologous primers. For miR-729, miR-4653, miR-878, mir-487b, miR-1288 and miR-743a-1, ovarian overexpression was not always significant, depending on the tissue, when QPCR was performed using homologous primers. This can probably be explained by the difficulty in designing primers without information on the exact mature miRNA sequence in medaka.

Among the miRNAs exhibiting strong expression in the ovary, miR-202 is of special interest. MiR-202 was previously shown to be expressed in the gonads of Atlantic halibut, rainbow trout, frog, chicken, and mice20,29,30,43. Moreover, sexually dimorphic expression of miR-202 was reported to occurs during gonadal development in both chicken and mouse, with predominant expression of the miRNA in the testis29,30. In agreement with existing data, we report here a strong overexpression of miR-202 in the medaka ovary and testis compared with non-reproductive tissues. This was further confirmed by QPCR using both zebrafish and medaka primers. Further analysis of our microarray revealed two probes from rat and mouse that exhibited strict ovarian-predominance. This suggests that miR-202-3p in medaka has an isomiR with a strict ovarian expression. Further characterization by small-RNA sequencing is required to determine its sequence and precisely analyze its function in gonads.

In addition, we report here 8 novel ovarian-predominant miRNAs (miR-4785, miR-6352, miR-4653, miR-878, miR-487, miR-1288, miR-743, miR-729) that were either never previously described in fish and/or never shown to be involved in oogenesis in any animal species. The ovarian-predominant expression of these miRNAs was thus previously unsuspected. Dre-miR-729 was characterized in medaka, where it was found in photoreceptor cells44. Rno-miR-878 is downregulated in rat liver fibrotic tissues45. Hsa-miR-487b is more widely expressed in endothelial and muscle cells in humans and mice, including in cancer cells46,47,48. Hsa-miR-1288 is upregulated in ectopic pregnancy patients49 and associated with the progression of colorectal cancer50. Mmu-miR-743a is expressed in mouse brain and testis and has possible roles in oxidative stress and neurodegeneration51,52. Hsa-miR-4785 is downregulated in human nasal epithelial cells treated with the TLR3 ligand poly(I:C)53.

For the 2 miRNAs (miR-4785 and miR-6352) that exhibited a strict ovarian-predominant expression, we predicted mRNA targets to identify potential cellular functions (Supplemental Fig. S6). Among the predicted targets of miR-4785 was fshr, a gene playing a major role in the ovary through its role in mediating Fsh (Follicle stimulating hormone) action on oogenesis in vertebrates. In zebrafish, disruption of fshr leads to a complete failure of follicle recruitment into vitellogenesis with all ovarian follicles arrested at the primary growth-previtellogenic transition54. Similarly, we analyzed the putative target genes of miR-6352 and we predicted the smg8, ddx20 and ddx6 genes. These later are all expressed in the ovary, according to the PhyloFish database. Smg8 encodes for a RNA binding protein that controls the maternal mRNA degradation and zygotic genome activation in the early embryo55,56. This information is consistent with a possible role of miR-6352 during the early embryonic development. MiR-6352 was also predicted to target ddx6 and ddx20 genes that encode transcriptional repressors. While ddx6 (DEAD-box protein-103/gemin3) is known to regulate the meiosis progression57, ddx20 directly represses the transcriptional activity of the transcription factor foxL2 and the steroidogenic factor SF-158,59. FoxL2 and SF-1 are both key genes for gonadal differentiation60,61. These data are consistent with a possible role of miR-6352 in ovarian development and oocyte formation.

Conclusion

Using microRNA microarrays, we identified 66 novel miRNAs predominantly expressed in medaka ovary. Of the miRNAs exhibiting the highest overabundance in the ovary, 20 were selected for further analysis. Using a combination of QPCR and in silico analyses, we identified 8 miRNAs (miR-4785, miR-6352, miR-4653, miR-878, miR-487, miR-1288, miR-743 and miR-729) that are ovarian-predominant, including 2 miRNAs that exhibit strict ovarian expression (miR-4785 and miR-6352). Of these 8 miRNAs, 7 were previously uncharacterized in fish (miR-4785, miR-6352, miR-4653, miR-878, miR-487, miR-1288 and miR-743). These results indicate that a significant number of ovarian-predominant miRNA genes are found in the medaka ovary, similarly to protein-coding genes. The strict ovarian expression of miR-4785 and miR-6352 suggest important roles in oogenesis and/or early development, possibly involving a maternal effect. Together, our findings provide new insights into the participation of ovarian-specific miRNAs in oogenesis and/or early embryonic development. Further analyses, including functional validation and target identification of these ovarian-predominant miRNAs, will be necessary to decipher their roles in the regulation of gene expression during oogenesis and early embryogenesis in fish.

Methods

Tissue collection

All experimental procedures were carried out in strict accordance with French and European regulations on animal welfare and were approved by the INRA LPGP Animal Care and Use Committee (no. M-2014-5-VT/M-2014-6-VT). Adult medaka (Oryzias latipes) from the CAB strain were raised at 28 °C under a reproduction photoperiod (14 hours light/10 hours dark). We collected samples corresponding to 10 different tissues (gills, heart, bone, muscle, kidney, intestine, liver, brain, ovary and testis) from 4 different females. In addition, testis samples were collected from four different males. Fishes were 4 months old and weighted 0.6 to 0.7 g for females and 0.5 to 0.6 g for males. All the samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction.

RNA extraction

Tissues were homogenized in Tri reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and total RNA was extracted according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was checked using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system. The presence of miRNAs in the samples was assessed using a small RNA chip (Agilent Technologies, USA) and RNA quantity was measured on a Nanodrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Microarray design

We used a microarray platform displaying 3800 distinct miRNAs from different vertebrate species (fish, birds and mammals). The design was performed as previously described using e-array custom platform (Agilent) with miRBase version 19.0 and subsequently deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the reference GPL2177620. For each target miRNA in miRBase, 16 probes were synthesized that were divided into two to four groups and have limited variations in sequence and size (one or two nucleotide differences at the 3′ and 5′ extremities). This led to robust miRNA expression analysis. All the available vertebrate miRNAs in miRBase version 19.0 (http://www.mirbase.org) were used (Oryzias latipes, Danio rerio, Fugu rubripes, Tetraodon nigroviridis, Cyprinus corpio, Hippoglossus hipoglossus and Paralichthys olivaceus). The miRNAs from rodents (Mus musculus and Rattus norvegicus), frogs (Xenopus laevis and Xenopus tropicalis), humans (Homo sapiens), and chickens (Gallus gallus) were subsequently added (Supplemental Fig. S5).

Microarray hybridization, data processing and miRNA annotation

Samples were processed and hybridized on the miRNA 8 × 60 K microarray as previously described, using the miRNA Microarray System with miRNA Complete Labeling and Hyb Kit (Agilent v2.2) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications20. Total RNA (200 ng) with labeling Spike-In was dephosphorylated for 30 minutes at 37 °C. RNA was denatured with DMSO at 100 °C for 7 minutes. RNA was then labeled by terminal ligation of cyanine3-pCp using T4 ligase for 2 hours at 16 °C. Purification of labeled RNA was done using Micro Bio-Spin column (Bio-Rad) to eliminate free cyanine3-pCp. Hybridization was performed with hybridizations Spike-In at 55 °C, 20 rpm for 20 hours. Slides were washed for 5 minutes with wash buffer 1 at room temperature and wash buffer 2 at 37 °C and immediately scanned. After labeling with cyanine3-pCp and RNA hybridization, slides were scanned with an Agilent Scanner (Agilent DNA Microarray Scanner; Agilent Technologies) using the following settings: profile = AgilentHD_miRNA, channels = Green, resolution = 3 μm, TIFF = 20 bit. Signal intensity was quantified using the Feature Extraction software (Agilent v10.7.3.1). Features with low signal (lower than three times the background level) were excluded. The data were processed using the GeneSpring software (Agilent v.13.0) using GmedianSignal values and subsequently normalized using quantile normalization. MiRNAs for which at least 8 of the 16 probes displayed a significant overexpression in the ovary, with at least 2-fold overabundance in the ovary in comparison to other tissues, were selected for further analysis as previously described20. Corresponding data were deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the reference GSE80823.

Genome mapping, RNA folding and homologous primers design

To identify the corresponding medaka miRNAs, the overabundant miRNA sequences were aligned (ENSEMBL BLAST using short sequences setting) on the medaka genome sequence available in ENSEMBL (release 83). Two to 4 hits with the best identity and coverage scores were considered as possible loci for the corresponding medaka miRNA gene(s). The corresponding genomic region of each hit was considered as the mature sequence and used to design the forward medaka homologous primers for QPCR. Each region was subsequently extended to the opposite arm to tentatively obtain the whole precursor sequence. These predicted sequences were then used for in silico prediction of the hairpin using the RNAfold web server with default settings62. We used −18 kcal/mol as a minimum free energy (MFE) threshold63.

Target prediction

The genes targeted by miR-4785 and miR-6352 were predicted using TargetScan64 and miRanda65 with default parameters. For TargetScan, we used TargetScan human and TargetScan mouse to predict miR-4785 and miR-6352 targets, respectively. For each miRNA, the 20 first candidates predicted by TargetScan were selected. Among them, genes predicted to be targeted by both algorithms (Targetscan and miRanda) were considered as putative targets.

Reverse transcription

Total RNA (100 ng) was reverse transcribed in a final volume of 10 μl. The reaction mixture included 1 μl of 10x poly(A) polymerase buffer, 0.1 mM of ATP, 1 μM of RT-primer, 0.1 mM of each deoxynucleotide (dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP), 100 units of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA) and 1 unit of poly(A) polymerase (New England Biolabs, USA). The reaction was then incubated at 42 °C for 1 hour, followed by enzyme inactivation at 95 °C for 5 minutes. The sequence of the reverse transcription primer was 5′-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTVN-3′ (where V is A, C or G and N is A, C, G or T).

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR (QPCR) was performed in 10 μl reactions containing the reverse transcription (RT) products (dilution 1:50), 100 nM of each primer and 1× SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (Fast SYBR Green Master Mix kit; Applied Biosystems) as indicated in the manufacturer’s instructions. QPCR was performed on a StepOnePlus thermocycler (Applied Biosystems) using the following program: (1) 95 °C for 3 minutes for the initial denaturation, (2) 40 cycles of 95 °C for 3 seconds, and (3) 60 °C for 30 seconds. The sequence of the universal reverse primer was 5′-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAG-3′. The sequences of the forward heterologous primers corresponded to the miRNA sequences present on the microarray (Supplemental Fig. S2). The sequences of the forward homologous primers corresponded to the genomic sequences identified on the medaka genome (Supplemental Fig. S4). The relative abundance of the target cDNA within a sample set was calculated from serially diluting the cDNA pool using Applied Biosystems StepOne software. Before analysis, miRNA expression was normalized to the reference gene 18 S66.

Statistical analyses

ANOVA was performed to detect differential expression between the different tissues in the microarray experiments. These analyses were followed by Benjamin-Hochberg correction. For QPCR analysis, we used p < 0.05 as a threshold and the Wilcoxon test for indicating significant differences between samples.

Additional Information

Accession codes: The array design (platform # GPL21776) and microarray expression data (accession # GSE80823) were deposited in the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/geo/).

How to cite this article: Bouchareb, A. et al. Genome-wide identification of novel ovarian-predominant miRNAs: new insights from the medaka (Oryzias latipes). Sci. Rep. 7, 40241; doi: 10.1038/srep40241 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the French national research Agency (ANR-13-BSV7-0015-Maternal Legacy to J.B.). The authors thank Cécile Duret for medaka rearing.

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.G. and T.N. participated in fish rearing, tissue collection, RNA extraction and QPCR analysis. A.L.C. performed the microarray analysis. J.M. performed bioinformatics analyses. A.B. drafted the manuscript, and participated in QPCR and microarray analyses and performed data analysis. V.T. and J.B. conceived the study, participated in data analysis and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- De Sousa P. A., Watson A. J., Schultz G. A. & Bilodeau-Goeseels S. Oogenetic and zygotic gene expression directing early bovine embryogenesis: a review. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 51, 112–121 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P. & Dean J. Oocyte-specific genes affect folliculogenesis, fertilization, and early development. Semin. Reprod. Med. 25, 243–251 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouleau A. et al. Maternally-inherited npm2 mRNA is crucial for egg developmental competence in zebrafish. Biol. Reprod. 91, 43–51 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvignes T. et al. X-Linked Retinitis Pigmentosa 2 Is a Novel Maternal-Effect Gene Required for Left-Right Asymmetry in Zebrafish. Biol. Reprod. 93, 42–42 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D. P. MicroRNAs. Cell 116, 281–297 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim L. P. Vertebrate MicroRNA Genes. Science (80-.). 299, 1540–1540 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempere L. F., Cole C. N., McPeek M. A. & Peterson K. J. The phylogenetic distribution of metazoan microRNAs: insights into evolutionary complexity and constraint. J. Exp. Zool. B. Mol. Dev. Evol. 306, 575–588 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F. et al. Maternal microRNAs are essential for mouse zygotic development. Genes Dev. 21, 644–648 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka M. et al. Impaired microRNA processing causes corpus luteum insufficiency and infertility in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 1944–1954 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez A. J. Zebrafish MiR-430 Promotes Deadenylation and Clearance of Maternal mRNAs. Science (80-.). 312, 75–79 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Fang Y., Liu Y. & Yang X. MicroRNAs in ovarian function and disorders. J. Ovarian Res. 8, 51 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins S. M. & Matzuk M. M. Oocyte-somatic cell communication and microRNA function in the ovary. Ann. Endocrinol. (Paris). 71, 144–148 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. & Rajkovic A. MicroRNAs and Mammalian Ovarian Development. Semin. Reprod. Med. 26, 461–468 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carletti M. Z. & Christenson L. K. MicroRNA in the ovary and female reproductive tract. J. Anim. Sci. 87, E29–E38 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripurani S. K., Xiao C., Salem M. & Yao J. Cloning and analysis of fetal ovary microRNAs in cattle. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 120, 16–22 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. et al. Microarray Analyses of Newborn Mouse Ovaries Lacking Nobox. Biol. Reprod. 77, 312–319 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro S. et al. Cloning and expression profiling of small RNAs expressed in the mouse ovary. RNA 13, 2366–2380 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q. et al. Identification and Differential Expression of microRNAs in Ovaries of Laying and Broody Geese (Anser cygnoides) by Solexa Sequencing. PLoS One 9, e87920 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quah S., Breuker C. J. & Holland P. W. H. A Diversity of Conserved and Novel Ovarian MicroRNAs in the Speckled Wood (Pararge aegeria). PLoS One 10, e0142243 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juanchich A., Le Cam A., Montfort J., Guiguen Y. & Bobe J. Identification of Differentially Expressed miRNAs and Their Potential Targets During Fish Ovarian Development. Biol. Reprod. 88, 128–128 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier J. et al. Gene evolution and gene expression after whole genome duplication in fish: the PhyloFish database. BMC Genomics 17, 368 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean J. Oocyte-specific genes regulate follicle formation, fertility and early mouse development. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 53, 171–180 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P. & Dean J. Oocyte-specific genes affect folliculogenesis, fertilization, and early development. Semin. Reprod. Med. 25, 243–251 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zheng P. & Dean J. Maternal control of early mouse development. Development 137, 859–70 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobe J., Nguyen T., Mahé S. & Monget P. In silico identification and molecular characterization of genes predominantly expressed in the fish oocyte. BMC Genomics 9, 499 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halm S., Ibanez A. J., Tyler C. R. & Prat F. Molecular characterisation of growth differentiation factor 9 (gdf9) and bone morphogenetic protein 15 (bmp15) and their patterns of gene expression during the ovarian reproductive cycle in the European sea bass. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 95–103 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns K. H. et al. Roles of NPM2 in chromatin and nucleolar organization in oocytes and embryos. Science 300, 633–6 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn H. W. et al. MicroRNA transcriptome in the newborn mouse ovaries determined by massive parallel sequencing. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 16, 463–471 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister S. C. et al. Manipulation of estrogen synthesis alters MIR202* expression in embryonic chicken gonads. Biol. Reprod. 85, 22–30 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright E. N. et al. SOX9 regulates microRNA miR-202-5p/3p expression during mouse testis differentiation. Biol. Reprod. 89, 34 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizuayehu T. T. et al. Sex-biased miRNA expression in Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) brain and gonads. Sex. Dev. Genet. Mol. Biol. Evol. Endocrinol. Embryol. Pathol. Sex Determ. Differ. 6, 257–266 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juanchich A. et al. Characterization of an extensive rainbow trout miRNA transcriptome by next generation sequencing. BMC Genomics 17, 164 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig N. et al. Distribution of miRNA expression across human tissues. Nucleic Acids Res (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juanchich A., Le Cam A., Montfort J., Guiguen Y. & Bobe J. Identification of Differentially Expressed miRNAs and Their Potential Targets During Fish Ovarian Development. Biol. Reprod (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Valverde S. L., Taft R. J. & Mattick J. S. Dynamic isomiR regulation in Drosophila development. RNA 16, 1881–1888 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loher P., Londin E. R. & Rigoutsos I. IsomiR expression profiles in human lymphoblastoid cell lines exhibit population and gender dependencies. Oncotarget 5, 8790–8802 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schamberger A. & Orbán T. I. 3′ IsomiR Species and DNA Contamination Influence Reliable Quantification of MicroRNAs by Stem-Loop Quantitative PCR. PLoS One 9, e106315 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L. W. et al. Complexity of the microRNA repertoire revealed by next-generation sequencing. RNA 16, 2170–2180 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braasch I. et al. Connectivity of vertebrate genomes: Paired-related homeobox (Prrx) genes in spotted gar, basal teleosts, and tetrapods. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 163, 24–36 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh Y.-H. E., Yi S. V. & Streelman J. T. Evolution of MicroRNAs and the Diversification of Species. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 55–65 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizuayehu T. T. & Babiak I. MicroRNA in Teleost Fish. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 1911–1937 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvignes T. et al. miRNA Nomenclature: A View Incorporating Genetic Origins, Biosynthetic Pathways, and Sequence Variants. Trends Genet (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armisen J., Gilchrist M. J., Wilczynska A., Standart N. & Miska E. A. Abundant and dynamically expressed miRNAs, piRNAs, and other small RNAs in the vertebrate Xenopus tropicalis. Genome Res. 19, 1766–75 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daido Y., Hamanishi S. & Kusakabe T. G. Transcriptional co-regulation of evolutionarily conserved microRNA/cone opsin gene pairs: implications for photoreceptor subtype specification. Dev. Biol. 392, 117–129 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.-Q. et al. The rno-miR-34 family is upregulated and targets ACSL1 in dimethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. FEBS J. 278, 1522–1532 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattolliat C.-H. et al. Expression of miR-487b and miR-410 encoded by 14q32.31 locus is a prognostic marker in neuroblastoma. Br. J. Cancer 105, 1352–1361 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng N. et al. miR-487b promotes human umbilical vein endothelial cell proliferation, migration, invasion and tube formation through regulating THBS1. Neurosci. Lett. 591, 1–7 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katase N., Terada K., Suzuki T., Nishimatsu S. & Nohno T. miR-487b, miR-3963 and miR-6412 delay myogenic differentiation in mouse myoblast-derived C2C12 cells. BMC Cell Biol. 16, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez F. et al. Embryonic miRNA profiles of normal and ectopic pregnancies. PLoS One 9, e102185 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan V. et al. Regulation of microRNA-1288 in colorectal cancer: altered expression and its clinicopathological significance. Mol. Carcinog. 53 Suppl 1, E36–44 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q. & Gibson G. E. Up-regulation of the mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase by oxidative stress is mediated by miR-743a. J. Neurochem. 118, 440–448 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T. et al. Identification and characterization of two novel classes of small RNAs in the mouse germline: retrotransposon-derived siRNAs in oocytes and germline small RNAs in testes. Genes Dev. 20, 1732–43 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata R. et al. Poly(I:C) induced microRNA-146a regulates epithelial barrier and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in human nasal epithelial cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 761, 375–382 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Lau S.-W., Zhang L. & Ge W. Disruption of Zebrafish Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor (fshr) But Not Luteinizing Hormone Receptor (lhcgr) Gene by TALEN Leads to Failed Follicle Activation in Females Followed by Sexual Reversal to Males. Endocrinology 156, 3747–62 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver J. D., Marsolais A. J., Smibert C. A. & Lipshitz H. D. Regulation and Function of Maternal Gene Products During the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition in Drosophila. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 113, 43–84 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H., Li X., Claycomb J. M. & Lipshitz H. D. The Smaug RNA-Binding Protein Is Essential for microRNA Synthesis During the Drosophila Maternal-to-zygotic Transition. G3 (Bethesda). (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smillie D. A. & Sommerville J. RNA helicase p54 (DDX6) is a shuttling protein involved in nuclear assembly of stored mRNP particles. J. Cell Sci. 115, 395–407 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouillet J.-F. et al. DEAD-box protein-103 (DP103, Ddx20) is essential for early embryonic development and modulates ovarian morphology and function. Endocrinology 149, 2168–75 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. et al. Transcriptional factor FOXL2 interacts with DP103 and induces apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 336, 876–81 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadovsky Y. & Dorn C. Function of steroidogenic factor 1 during development and differentiation of the reproductive system. Rev. Reprod. 5, 136–42 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertho S. et al. Foxl2 and Its Relatives Are Evolutionary Conserved Players in Gonadal Sex Differentiation. Sex Dev. 10, 111–29 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber A. R., Lorenz R., Bernhart S. H., Neubock R. & Hofacker I. L. The Vienna RNA Websuite. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W70–W74 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal V., Bell G. W., Nam J. -W. & Bartel D. P. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright A. J. et al., MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 5, R1 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. & He S. A bioinformatics-based update on microRNAs and their targets in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Gene 533, 261–269 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio M. V. et al. MicroRNA Signatures in Human Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 8699–8707 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.