Abstract

Potato chips can be considered as an ideal carrier for targeted nutrient/s delivery as mostly consumed by the vulnerable group (children and teen agers). The present study was planned to fortifiy potato chips with calcium (Calcium lactate) and zinc (Zinc sulphate) using vacuum impregnation technique. At about 70–80 mm Hg vacuum pressure, maximum level of impregnation of both the minerals was achieved. Results showed that after optimization, calcium lactate at 4.81%, zinc sulphate at 0.72%, and vacuum of 33.53 mm Hg with restoration period of 19.52 min can fortify potato chips that can fulfil 10 and 21% need of calcium and zinc, respectively of targeted group (age 4–17 years). The present research work has shown that through this technique, fortification can be done in potato chips which are generally considered as a poor source of minerals. Further to make potato chips more fit to health conscious consumers, rather frying microwaving was done to develop mineral fortified low fat potato chips.

Keywords: Vacuum impregnation, Fortification, Potato chips, Calcium, Zinc

Introduction

Potato (Solanum tuberosum, L.) is one of the most important tuber crops widely consumed in the world. It ranks fifth in terms of human consumption and fourth in worldwide production (Marwaha et al. 2010). It is widely consumed non cereal crops by mass population which can provide bulk to their diet at low cost. Moreover, the snacks produced by the potatoes like chips and french fries are highly popular among the children (age 4–17) who are vulnerable for nutrient deficiency particularly minerals (Villagomez and Ramtekkar 2014). Affordable price, easy availability, and wide consumption are the considerable factors which make potato chips an ideal carrier for fortification/enrichment. Keeping these facts in view, an experiment was planned to incorporate minerals particularly calcium and zinc in potato chips through vacuum impregnation technique.

Calcium is one of the most important minerals and primarily responsible for growth and maintenance of skeletal system in human body and hence categorised as a macro element (Anderson 1999). The discrepancy between calcium intake and recommendations has led manufacturers to market an increasing number and variety of calcium-fortified products (Konar et al. 2015). Similarly, zinc is involved in many biochemical processes like cellular respiration, cellular utilization of oxygen, DNA and RNA reproduction, maintenance of cell membrane integrity, and sequestration of free radicals etc. (Chan et al. 1998). Though zinc is considered as a micronutrient, still the conservative estimates suggested that more than 25% of the world’s population is at risk of zinc deficiency (Maret and Sandstead 2006).

In recent years, vacuum impregnation has emerged as a useful tool for incorporating physiologically active compounds into the porous structure of fruits and vegetables without disturbing their cellular structure (Martinez-Monzo et al. 1998; Gras et al. 2003; Betoret et al. 2003; Barrera et al. 2004; Alzamora et al. 2005, Anino et al. 2006). Shelf life extension through calcium impregnation in fresh whole and minimally processed fruits and vegetables has already been reported by (Marti´n-Dianaa et al. 2007) through vacuum. Calcium fortification in various vegetables except potatoes by applying vacuum impregnation is an alternative in developing functional foods has been reported by Gras et al. (2003). Zinc enrichment in whole potato tuber by vacuum impregnation has recently been done by Erihemu et al. (2015). To the best knowledge of the authors, this is the first effort to fortify low fat potato chips with minerals using vacuum impregnation technique.

Materials and methods

Raw materials and sample preparation

Fresh harvest of potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) cv. Kufri Chipsona-2 was procured from CPRI Regional Station Modipuram (CPRC, Modipuram), Uttar Pradesh, India. The peels (upper ~1.5 mm layer) were removed manually using a stainless steel peeler. Chips were prepared using a commercial chips cutter (Make: Felix wafer maker Slim, Om Appliances, Rajkot, India) with an average thickness of 1.67 ± 0.058 mm as measured by Vernier caliper.

Fortificants and carrier

Calcium lactate and Zinc sulphate (food grade) were used as fortificants (GRAS substances). Mixture of calcium lactate and zinc sulphate solution of different concentrations were used for impregnation keeping their high bio-availability (≥90%), water solubility and neutral effect on taste and colour of the product in view (Matsumoto et al. 1989; Spears et al. 2004). For these fortificants potato chips were used as a carrier. Since the standard RDI values (www.lenntech.com/recommended-daily-intake.htm 2015) of each mineral was based on 2000 cal intake for people of 4–17 years of age therefore, research work was planned in such a manner that the targeted level (10% RDI for calcium and 21% RDI for zinc) of particular mineral can be achieved by consuming 30 g serving which is Recommended Amount Customarily Consumed (RACC), for potato chips.

Vacuum impregnation process

Vacuum was created in a closed chamber in which raw potato chips were kept in a single layer on perforated base. After the desirable vacuum level for set time (15 min for each run) was achieved, raw chips were immediately exposed to fortificants solution mixture of particular concentration in the ratio of 1:3 (w/v) to a predefined restoration time at atmospheric pressure.

Low fat potato chips preparation

Potato chips were prepared by microwave processing by using a methodology reported by Joshi et al. (2016). In this method un-blanched raw potato chips (control and mineral fortified) were exposed to 2.5–3 min at 600 W in microwave. The chips thus developed had approximately 90 per cent lesser fat than its conventional counterparts (Joshi et al. 2016).

Mineral content estimation

Calcium and zinc content of controlled, commercial and experimental potato chips were measured through Microwave Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (MPAES) from Agilent Technologies 4100 MP AES, USA with the accuracy of ±0.1 ppm having plasma temperature of approximately 6000 °C. For estimation, 0.5 g of defatted sample was digested with concentrate nitric acid in three cycles of 25, 30 and 60 min of digestion at 80, 120 and 140 °C, respectively for complete digestion. The digested mixture upon appropriate dilution (~200 times) was estimated for calcium and zinc content simultaneously at the wavelength of 393.37 and 213.86 nm, respectively.

Experimental design

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was used for process optimization. A four-factor three level Box-Behnken design was used to evaluate the combined effect of four independent variables calcium concentration, zinc concentration, vacuum level, restoration time, coded as X 1, X 2, X 3, X 4, respectively on impregnation level of calcium and zinc in potato chips. The minimum and maximum values for calcium concentration, zinc concentration, vacuum level, and restoration time were set at 5–15%, 1–3%, 30–90 mm Hg, 10–20 min, respectively keeping constant solid to liquid ratio (~1:3 w/v) during whole experiment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Independent variables and their coded and actual values used for optimization

| Independent variable | Units | Symbol | Code levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Calcium salt concentration | % | X 1 | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| Zinc salt concentration | % | X 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Vacuum level | mm Hg | X 3 | 30 | 60 | 90 |

| Restoration time | min | X 4 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

The response values of the experimental design were calcium and zinc content in potato chips (mg/100 g). A total of 27 runs (trials) were carried out and the responses were taken by repeating each trial thrice to see the change in responses (Table 2). The response function (Y) was partitioned into linear, quadratic and interactive components as mentioned below:

where Y is the response; Xi, Xj, are input variables; is the intercept; are linear coefficient; are quadratic coefficients; are interaction coefficients.

Table 2.

The Box-Behnken design and experiment data for mineral impregnation inpotato chips

| Treat | Independent variables | Dependent variables (mineral content in potato chips) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 (% Calcium) | X2 (% Zinc) | X3 (Vac, mm Hg) | X4 (Rest Time, min) | Zn (mg/100 g) | Ca (mg/100 g) | ||

| 1. | 5 | 1 | 60 | 15 | 192.03 | 161.94 | |

| 2. | 15 | 1 | 60 | 15 | 25.45 | 440.07 | |

| 3. | 5 | 3 | 60 | 15 | 256.78 | 180.11 | |

| 4. | 15 | 3 | 60 | 15 | 155.90 | 559.02 | |

| 5. | 10 | 2 | 30 | 10 | 24.31 | 204.93 | |

| 6. | 10 | 2 | 90 | 10 | 64.97 | 306.74 | |

| 7. | 10 | 2 | 30 | 20 | 103.33 | 432.43 | |

| 8. | 10 | 2 | 90 | 20 | 71.95 | 279.87 | |

| 9. | 10 | 2 | 60 | 15 | 149.41 | 461.76 | |

| 10. | 5 | 2 | 60 | 10 | 253.71 | 224.46 | |

| 11. | 15 | 2 | 60 | 10 | 110.81 | 699.91 | |

| 12. | 5 | 2 | 60 | 20 | 154.83 | 266.95 | |

| 13. | 15 | 2 | 60 | 20 | 90.25 | 727.18 | |

| 14. | 10 | 1 | 30 | 15 | 7.47 | 188.92 | |

| 15. | 10 | 3 | 30 | 15 | 81.73 | 457.36 | |

| 16. | 10 | 1 | 90 | 15 | 42.19 | 379.74 | |

| 17. | 10 | 3 | 90 | 15 | 61.23 | 421.34 | |

| 18. | 10 | 2 | 60 | 15 | 133.34 | 457.39 | |

| 19. | 5 | 2 | 30 | 15 | 109.12 | 165.12 | |

| 20. | 15 | 2 | 30 | 15 | 52.69 | 485.46 | |

| 21. | 5 | 2 | 90 | 15 | 155.99 | 338.67 | |

| 22. | 15 | 2 | 90 | 15 | 193.87 | 220.22 | |

| 23. | 10 | 1 | 60 | 10 | 56.36 | 534.45 | |

| 24. | 10 | 3 | 60 | 10 | 180.08 | 351.34 | |

| 25. | 10 | 1 | 60 | 20 | 226.79 | 462.66 | |

| 26. | 10 | 3 | 60 | 20 | 58.06 | 486.02 | |

| 27. | 10 | 2 | 60 | 15 | 138.88 | 484.69 | |

Sensory evaluation

Sensory evaluation of optimized products was conducted based on 9 point Hedonic scale for colour, texture, taste, aroma, overall acceptably. A semi trained panel of 15 members was selected to evaluate the sensory properties of the fortified potato chips. The sensory evaluation was performed in laboratory with clean sensory cabinets containing fresh water. The panellists were instructed to evaluate the sample in comparison with control (microwave potato chips) (Larmond 1977).

Statistical analysis

The statistical evaluation was performed by running analysis of variance (ANOVA) and regression calculation using SAS (version 11). Each factor had three levels which were coded as −1,0 and 1. The central points (coded as 0) for each factor were 10% calcium lactate, 2% zinc sulphate, 60 mm Hg vacuum pressure and 15 min restoration time. Surface plots and equations were derived from STATISTICA Version 5.0 software.

Results and discussion

Using Vacuum Impregnation technique, it was possible to raise the calcium level in low fat potato chips from 93.3 to 727.18 mg/100 g. Similarly, the zinc levels could be raised from 1.68 to 256.78 mg/100 g when compared to commercial fried potato chips preparations. The regression analysis indicated that the calcium and zinc content in potato chips was a function of vacuum level, restoration time, calcium and zinc content in impregnation solution. The Box–Behnken design was used to optimize the process for targeted level of mineral impregnation in potato chips. The goal for fortification was set at 262 mg for calcium and 10 mg for zinc per 100 g of chips.

For impregnation study, the results of 27 experiment runs with completed design are shown in Table 2, and the range of impregnation for calcium and zinc was found to vary from 161.94 ± 1.54 to 727.18 ± 4.86 and 7.47 ± 2.08 to 256.78 ± 2.08 mg/100 g, respectively.

Effect of process variables on zinc impregnation

It was observed that as the zinc concentration increased in the solution; impregnation level of zinc in chips increased significantly (p ≤ 0.05) in linear fashion. Similarly, as the level of vacuum increased, the impregnation level increased initially but decreased afterwards. It can be seen that the highest level of impregnation was achieved at about 60 mm Hg (Fig. 1a-i). It may be due to the fact that 60 mm Hg vacuum was sufficient to remove the air from the pores of thin potato slices (avg thickness ~1.67 mm) therefore, the highest level of impregnation of zinc (256.77 mg/100 g) was achieved at about 60 mm Hg keeping other factors constant (Table 2).

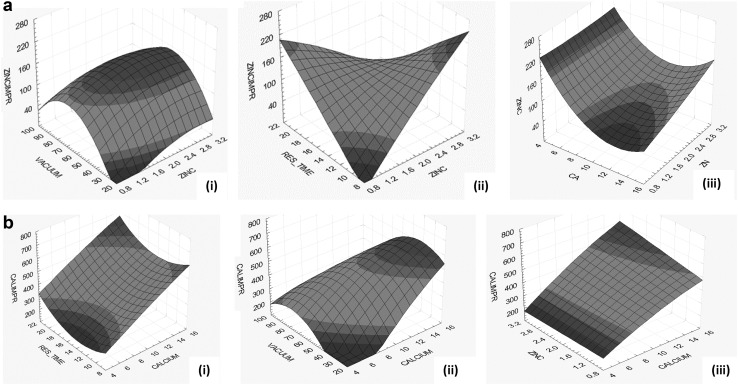

Fig. 1.

a Effect of i Vacuum and Zinc ion concentration ii Restoration time and Zinc ion concentration iii Zinc and Calcium ion concentration on zinc impregnation level in potato chips. b Effect of i Calcium ion concentration and Restoration time ii Vacuum and Calcium ion concentration iii Zinc and Calcium ion concentration on calcium impregnation level in potato chips

With increase in restoration time from 10 to 22 min, the zinc content increased and reached approximately 220 mg/100 g of potato chips (Fig. 1a-ii). It was also observed that after a certain concentration, zinc impregnation level was unaffected for any increase in concentration of zinc ions in the solution (Fig. 1a-iii).

Effect of zinc ion concentration (X) and vacuum level (Y), effect of zinc ion and restoration time (y) and effect of zinc and calcium ion concentration (Y) in impregnation solution on zinc (Z) impregnation can be calculated by the Eqs 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

As far the whole model was concerned, the model was significant (p ≤ 0.05) having F value 2.55 and R-square 0.8812. The value of adequate precision which measures signal to noise ratio of any model was 5.425 (≥4.0) which showed that the model can be used to navigate the design space.

Effect of process variables on calcium impregnation

It was observed that as the calcium concentration increased in the solution; impregnation level of calcium in chips increased linearly and reached up to 700 mg/100 g (Fig. 1b-i). Presence of vacuum had significant effect (p ≤ 0.05) on calcium impregnation level initially as linear function followed by quadratic function in later stage (Fig. 1b-ii). Maximum level of impregnation was achieved within 70–80 mm Hg range. With the help of vacuum, calcium impregnation in apple tissues was done by Alzamora et al. (2005) however, the restoration time in supported study was three–sixfolds higher than the reported work. This may be due to dimensional difference of apple tissue from potato chips which was cylindrical shape in the supported study (1.5 cm in diameter and 2 cm in length). It was also observed in Fig. 1b-iii that zinc ions did not affect the calcium impregnation process however it was not in the case of effect of calcium ions on zinc impregnation (Fig. 1a-iii). It may be due to the higher proportion of calcium ion in comparison with zinc ion concentration in each fortificant mixture of the experiment set (Table 2). Effect of calcium ion concentration (X) and restoration time (Y), effect of calcium and zinc ion concentration (y) and effect of calcium ion concentration and vacuum (Y) on calcium impregnation in potato chips (Z) can be calculated by the Eqs. 4, 5 and 6, respectively.

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

As far the whole model is concerned, the model was significant (p ≤ 0.05) having F value 2.88 and R-square 0.9011. The value of adequate precision which measures signal to noise ratio was 6.989 (≥4.0). This shows that the model can be used to navigate the design space.

Optimization and validation

Mean optimized values for calcium lactate concentration, zinc sulphate concentration, vacuum level and restoration period were 4.81%, 0.72%, 33.53 mm Hg and 19.52 min, respectively as derived from the software, can fulfill 10% RDI need of calcium and 21% RDI need of zinc of targeted group, with 95% of confidence limit.

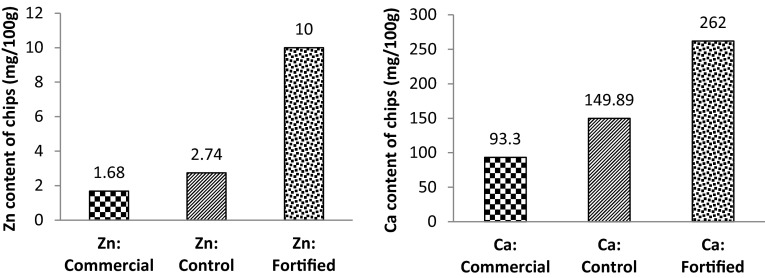

The developed potato chips using optimized conditions can be considered as good source of calcium and zinc with acceptable overall acceptability scores (≥7.8 on 9.0 point Hedonic scale versus 8.0 of control preparation) as in comparison, fortified potato chips had calcium and zinc content 1.7 and 3.6 times higher than that of control preparation, respectively (Fig. 2). However, this difference would be more in comparison with commercial preparation as can be seen in the Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Comparative chart for Mineral content in various types of chips

Conclusion

Vacuum Impregnation can be a promising way for calcium and zinc fortification in potato chips. Similar strategy can be applied for other minerals also as per the requirements of targeted group. The level of desirability from zinc salt can be achieved at a very low concentration of zinc salt (<1.0%). This shows that for zinc impregnation, costly compounds like nano zinc compounds can be explored which are more bioavailable and will be required in lesser amount, provided they should be water soluble and safe for consumption. Potato’s porous nature provides great opportunity in the form of ideal matrix to impregnate bioactive/functional/essential components through osmosis assisted by vacuum. Therefore, vacuum impregnation technique can be used as an economically feasible technique to fortify the potato based snacks which are generally considered as‘Junk Foods’with essential nutrients having potential health benefits.

References

- Alzamora SM, Salvatori D, Tapia MS, López-Malo A, Welti-Chanes J, Fito P. Novel functional foods from vegetable matrices impregnated with biologically active compounds. J Food Eng. 2005;67(1–2):205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.05.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JJB (1999) Macroelements water and electrolytes in sport nutrition. Driskell JA, Wolinsky I. (ed.). Chapter-I: Introduction to macroelements water and electrolytes in sport nutrition. pp 11

- Anino SV, Salvatori DM, Alzamora SM. Changes in calcium level and mechanical properties of apple tissue due to impregnation with calcium salts. Food Res Int. 2006;39(2):154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2005.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera C, Betoret N, Fito P. Ca2+ and Fe2+ influence on the osmotic dehydration kinetics of apple slices (var. Granny Smith) J Food Eng. 2004;65(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2003.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betoret N, Puente L, Díaz MJ, Pagán MJ, García MJ, Gras ML, Martínez-Monzó J, Fito P. Development of probiotic-enriched dried fruits by vacuum impregnation. J Food Eng. 2003;56(2–3):273–277. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(02)00268-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S, Gerson B, Subramaniam S. The role of copper, molybdenum, selenium, and zinc in nutrition and health. J Lab Clin Med. 1998;18:673–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erihemu Hironaka K, Koaze H, Oda Y, Shinanda K. Zinc enrichment of whole potato tuber by vacuum impregnation. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(4):2352–2358. doi: 10.1007/s13197-013-1194-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras ML, Vidal D, Betoret N, Chiralt A, Fito P. Calcium fortification of vegetables by vacuum impregnation interactions with cellular matrix. J Food Eng. 2003;56:279–284. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(02)00269-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, Rudra SG, Sagar VR, Raigond P, Dutt S, Singh B, Singh BP. Development of low fat potato chips through microwave processing. J Food Sci Technol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2304-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konar N, Poyrazoglu ES, Artik N. Influence of calcium fortification on physical and rheological properties of sucrose-free prebiotic milk chocolates containing inulin and maltitol. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(4):2033–2042. doi: 10.1007/s13197-013-1229-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larmond E. Laboratory methods for sensory evaluation of foods. Ottawa: Canada Department of Agriculture; 1977. p. 1637. [Google Scholar]

- Maret W, Sandstead HH. Zinc requirements and the risks and benefits of zinc supplementation. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2006;20:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martı´n-Dianaa AB, Ricoa D, Frı´asa JM Baratb JM, Henehana GTM, Barry-Ryana C. Calcium for extending the shelf life of fresh whole and minimally processed fruits and vegetables: a review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2007;18:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2006.11.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Monzo J, Martinez-Navarrete N, Chiralt A, Fito P. Mechanical and structural changes in apple (Var. Granny Smith) due to vacuum impregnation with cryoprotectants. J Food Sci Technol. 1998;63(3):499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Marwaha RS, Pandey SK, Kumar D, Singh SV, Kumar P. Potato processing scenario in India: industrial constraints, future projections, challenges ahead and remedies—a Review. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47(2):137–156. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0026-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S, Arai M, Yamaguchi M, Togari A, Ohira T, Takei H, Kohsaka M. Comparisons of bioavailability of various calcium salts. Utilization incisor dentin in parathyroidectomized rats. Aichi Gakuin Daigaku Shigakkai Shi. 1989;27(4):1029–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears JW, Schlegel P, Seal MC, Lloyd KE. Bioavailability of zinc from zinc sulphate and different organic zinc sources and their effects on ruminal volatile fatty acid proportions. Livest Prod Sci. 2004;90(2–3):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.livprodsci.2004.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villagomez A, Ramtekkar U. Iron, magnesium, vitamin D, and zinc deficiencies in children presenting with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child. 2014;1:261–279. doi: 10.3390/children1030261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- www.lenntech.com/recommended-daily-intake.htm(2015) Recommended daily intake of vitamins and minerals. Accessed 04 March 2015