Abstract

In a retrospective study performed over 6 years in Brazil, Fusarium solani was found to be the most common species causing mycotic keratitis. The genetic diversity of 44 isolates from 39 patients was assessed by enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR (ERIC-PCR) and PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) fingerprinting. ERIC-PCR was more discriminatory than PCR-RFLP for differentiating the strains. By combining of the results of both techniques, we identified 40 genotypes. Molecular typing revealed a high genomic heterogeneity of the strains of F. solani studied.

Fusarium is a common fungus that causes ocular infections in humans (2, 12), with keratitis being the most frequent clinical manifestation. The most frequent species of Fusarium causing keratitis are Fusarium solani and Fusarium oxysporum (15, 17). More rarely, Fusarium dimerum (15), Fusarium verticillioides, Fusarium sacchari (17), and very recently, Fusarium polyphialidicum (5) have also been reported. Keratitis is more common in tropical and subtropical areas. Its incidence correlates with harvest time and seasonal increases in temperature and humidity (2). A high incidence of fusariosis, especially in immunocompromised patients, has been found in different regions of the world. However, the incidence of such fungi in ocular infections are unknown. In this study, we have determined the incidence of Fusarium in Brazil. For this purpose, we have performed a retrospective study of all cases of mycotic keratitis diagnosed over a period of 6 years at a referral eye care center that treats patients from both urban and rural areas. We also carried out the molecular genotyping of F. solani, the most common species, to evaluate its genetic diversity and to determine whether some strains are prevalent in the area studied. To test the fungi, we used two common molecular techniques, enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR (ERIC-PCR) and PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal isolates and culture conditions.

All cases of fungal keratitis diagnosed over a 6-year period (1996 to 2002) in the Microbiology Laboratory of the Ophthalmology Department of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo were reviewed. The Ophthalmology Department is a referral center that treats patients from all over Brazil. Diagnosis was established by direct examination of corneal scrapings positive for fungal elements and repeated cultures of the same fungus. The samples were handled as previously described (6, 12). Fungal isolates were identified according to the method of de Hoog et al. (3).

A total of 44 isolates of F. solani, including 35 epidemiologically unrelated isolates, and 9 isolates obtained from 4 patients were cultured on potato dextrose agar (Pronadisa, Madrid, Spain) at 25°C and tested by ERIC-PCR and PCR-RFLP analysis of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA), including ITS1, 5.8S rDNA, ITS2, and the D1-D2 region of the 28S rDNA.

DNA extraction.

Genomic DNA was extracted and purified directly from fungal colonies by using the Fast DNA kit (Bio101, Vista, Calif.) and a FastPrep FP120 instrument (Thermo Savant, Holbrook, N.Y.) to disrupt the fungal cells. The DNA was quantified with the GeneQuant pro (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Cambridge, England).

ERIC-PCR.

The ERIC-PCR was performed in a volume of 50 μl containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 μM concentrations of the ERIC primers ERIC-1 and ERIC-2 (13), 10 ng of genomic DNA, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Roche Molecular System, Alameda, Calif.). The following PCR conditions were used with a model 2400 thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.): 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 52°C, and 8 min at 65°C and a final extension of 16 min at 65°C. Amplified products were resolved by electrophoresis in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer with a 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel, stained with ethidium bromide for 30 min, and photographed. An AmpliSize molecular ruler 50- to 2,000-bp ladder (Bio-Rad, Barcelona, Spain) (8 μl) was electrophoresed twice in each gel. Reactions were carried out three times to confirm reproducibility.

PCR-RFLP.

PCR was performed with primer pair ITS5-NL4b (10, 16). The PCR mixtures (50-μl volume) contained 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 μM concentrations of each primer, 10 ng of genomic DNA, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Roche Molecular Systems). Amplification was carried out with the following temperature profiles: initial denaturation of 5 min at 95°C; followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min 30 s at 72°C; and a final extension of 7 min at 72°C. Aliquots (7.5 μl) of PCR products were digested for 20 h with 5 U of restriction endonucleases. The restriction enzymes used were HaeIII, MboI, NarI, CfoI, and AluI. The restriction fragments were separated by electrophoresis in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer with a 17% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel, stained with ethidium bromide for 30 min, and photographed.

Data analysis.

Gel images were saved as TIFF files, normalized with the above mentioned molecular size marker, and further analyzed with BioNumerics software, version 1.5 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). DNA bands detected by computer were carefully verified by visual examination to correct unsatisfactory detection. Fingerprints were assigned to a different type when any band differences were observed. Variations in band intensity were not considered to be differences. To construct the dendrograms, levels of similarity between the profiles were calculated by using the band-matching Dice coefficient (SD) and the cluster analysis of similarity matrices was calculated with the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA). A band-matching tolerance of 0.9% was chosen, and similarity matrices of whole densitometric curves of the gel tracks were calculated by using the pairwise Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient (r value) (14). PCR-RFLP products of each enzyme were analyzed together to increase the technique's discriminatory power.

RESULTS

One hundred fifty-two cases of fungal keratitis were diagnosed during the period studied. The most common genus identified was Fusarium, which was isolated from 68 patients (44.6%). The most frequent species were F. solani (62 patients), followed by F. verticillioides (3 patients), F. oxysporum (2 patients), and F. dimerum (1 patient). Other relevant species were Candida albicans (25 patients), Paecilomyces lilacinus (10 patients), and Aspergillus flavus (7 patients). Aspergillus fumigatus was only isolated on two occasions.

Molecular genotyping.

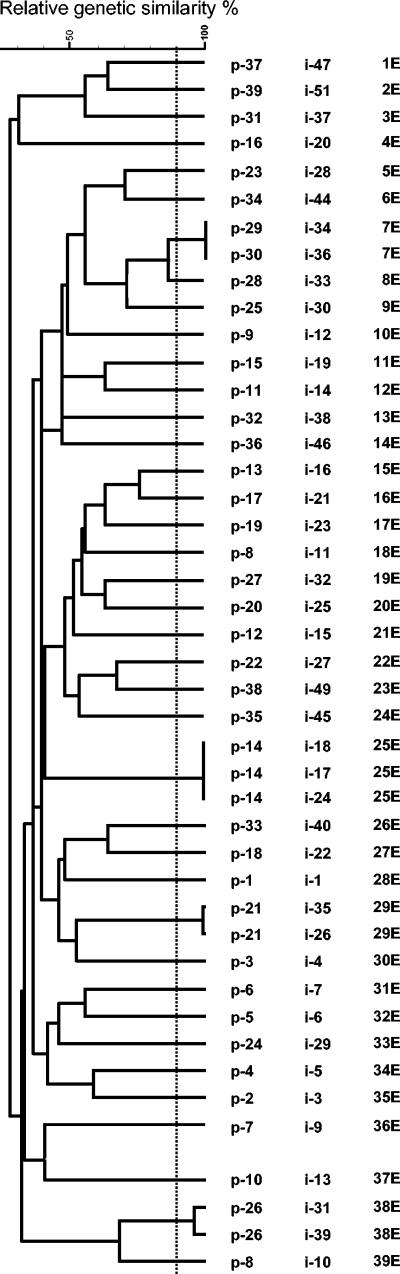

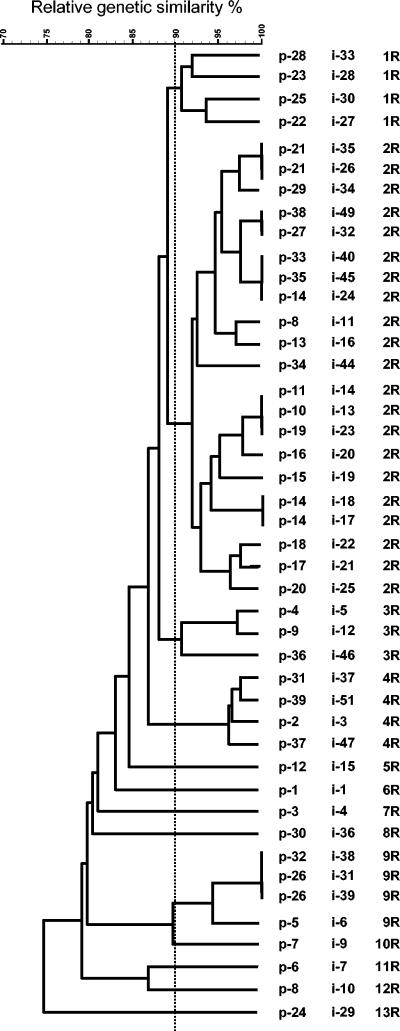

The fingerprints obtained with ERIC-PCR comprised 12 to 27 amplification bands ranging in size from 0.1 to 2.1 kb. Thirty-nine groups were obtained with the 44 isolates (Table 1; Fig. 1). Among epidemiologically related isolates (same patient), a relative genetic similarity of >90% was obtained for two pairs of isolates and one group of three isolates, i.e., the two isolates from patients 26 (95%) and 21 (98%) and the three isolates from patient 14 (100%), respectively. Among unrelated isolates (different patients), a relative genetic similarity of 100% was obtained for the isolates recovered from patients 29 and 30. The fingerprints obtained with PCR-RFLP comprised 1 to 8 amplification bands ranging in size from 0.1 to 1.2 kb. Thirteen groups were observed with the 44 isolates (Table 1; Fig. 2). Some of the isolates that were highly related by ERIC-PCR were also closely related by PCR-RFLP, i.e., those from patients 26 (100%) and 21 (100%), but in general, different groupings were obtained. Two of the three isolates from patient 14 also showed a relative genetic similarity of 100%, but the third was placed further away, although within the same group as the other two. The two isolates from patients 29 and 30, which showed a relative genetic similarity of 100% by ERIC-PCR, were placed in different groups by PCR-RFLP. Using the results from both techniques, we obtained 40 combined genotypes (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics and genotypes of patients with fusarial keratitisa

| Patient no. | Isolate no. | Sex | Age (yr) | Date (mo/day/yr) of isolation | ERIC-PCR type | PCR-RFLP type | Combined type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-1 | i-1 | F | 38 | 04/30/96 | 28E | 6R | 1ER |

| p-2 | i-3 | M | 36 | 05/15/96 | 35E | 4R | 2ER |

| p-3 | i-4 | F | 40 | 10/24/96 | 30E | 7R | 3ER |

| p-4 | i-5 | M | 43 | 04/13/98 | 34E | 3R | 4ER |

| p-5 | i-6 | M | 68 | 05/05/99 | 32E | 9R | 5ER |

| p-6 | i-7 | M | 44 | 05/03/00 | 31E | 11R | 6ER |

| p-7 | i-9 | M | 76 | 07/23/00 | 36E | 10R | 7ER |

| p-8 | i-10 | M | 20 | 08/18/00 | 39E | 12R | 8ER |

| i-11 | 08/20/00 | 18E | 2R | 9ER | |||

| p-9 | i-12 | F | ? | 09/05/00 | 10E | 3R | 10ER |

| p-10 | i-13 | F | 31 | 01/13/02 | 37E | 2R | 11ER |

| p-11 | i-14 | M | 33 | 08/11/96 | 12E | 2R | 12ER |

| p-12 | i-15 | M | 20 | 02/18/97 | 21E | 5R | 13ER |

| p-13 | i-16 | M | 56 | 07/27/97 | 15E | 2R | 14ER |

| p-14 | i-17 | F | 27 | 02/26/98 | 25E | 2R | 15ER |

| i-18 | 03/01/98 | 25E | 2R | 15ER | |||

| i-24 | 03/11/98 | 25E | 2R | 15ER | |||

| p-15 | i-19 | M | 63 | 07/13/98 | 11E | 2R | 16ER |

| p-16 | i-20 | M | 35 | 09/29/98 | 4E | 2R | 17ER |

| p-17 | i-21 | M | 52 | 02/06/99 | 16E | 2R | 18ER |

| p-18 | i-22 | F | 73 | 05/17/99 | 27E | 2R | 19ER |

| p-19 | i-23 | M | 15 | 08/09/00 | 17E | 2R | 20ER |

| p-20 | i-25 | M | 36 | 03/28/99 | 20E | 2R | 21ER |

| p-21 | i-26 | M | 18 | 11/22/99 | 29E | 2R | 22ER |

| i-35 | 11/29/99 | 29E | 2R | 22ER | |||

| p-22 | i-27 | F | 39 | 06/08/00 | 22E | 1R | 23ER |

| p-23 | i-28 | M | 41 | 08/28/00 | 5E | 1R | 24ER |

| p-24 | i-29 | M | 29 | 10/10/00 | 33E | 13R | 25ER |

| p-25 | i-30 | M | 39 | 12/21/00 | 9E | 1R | 26ER |

| p-26 | i-31 | F | 41 | 12/04/01 | 38E | 9R | 27ER |

| i-39 | 12/08/01 | 38E | 9R | 27ER | |||

| p-27 | i-32 | M | 39 | 01/22/02 | 19E | 2R | 28ER |

| p-28 | i-33 | M | 31 | 01/13/98 | 8E | 1R | 29ER |

| p-29 | i-34 | M | 46 | 06/21/99 | 7E | 2R | 30ER |

| p-30 | i-36 | F | 33 | 02/22/00 | 7E | 8R | 31ER |

| p-31 | i-37 | M | ? | 01/24/92 | 3E | 4R | 32ER |

| p-32 | i-38 | F | 39 | 06/04/00 | 13E | 9R | 33ER |

| p-33 | i-40 | F | 40 | 10/29/96 | 26E | 2R | 34ER |

| p-34 | i-44 | M | 59 | 02/19/99 | 6E | 2R | 35ER |

| p-35 | i-45 | F | 48 | 11/13/99 | 24E | 2R | 36ER |

| p-36 | i-46 | M | 25 | 12/01/97 | 14E | 3R | 37ER |

| p-37 | i-47 | M | 44 | 04/12/00 | 1E | 4R | 38ER |

| p-38 | i-49 | F | 42 | 07/12/01 | 23E | 2R | 39ER |

| p-39 | i-51 | F | 43 | 07/24/02 | 2E | 4R | 40ER |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; E, ERIC-PCR genotype; R, PCR-RFLP genotype; ER, combined ERIC/RFLP genotype; ?, unknown.

FIG. 1.

SD and UPGMA cluster analysis based on ERIC-PCR-produced patterns. First column, patient number; second column, isolate number; third column, ERIC type.

FIG. 2.

SD and UPGMA cluster analysis based on the combined AluI, CfoI, HaeIII, MboI, and NarI RFLP-produced patterns. First column, patient number; second column, isolate number; third column, PCR-RFLP type.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that F. solani is clearly the most common fungus causing keratitis, at least in the geographical region studied. This is, to our knowledge, the most extensive survey carried out in South America and seems to confirm that Fusarium is the most prevalent fungus on that continent. Other authors, though studying only a small number of cases, had indicated that this fungus was the most common cause of keratitis in Paraguay (9) and Argentina (18). Despite the high incidence of Fusarium, and although its ability to infect the eye has been demonstrated in numerous studies (2, 12), it is unknown whether only a few strains have this ability for eye invasion or whether this is a general feature of all strains of F. solani. This issue is key to determining the epidemiology of these infections. At least at the morphological and cultural levels, no differences were observed between environmental and corneal isolates of F. solani (12). Our study demonstrated a high heterogeneity in the genotypes of the isolates of F. solani causing keratitis. With a few exceptions, only those isolates collected from the same patient shared the same genotype. The fact that practically all of the cases included in the study were caused by trauma and that the fungi were implanted directly into the cornea through vegetable matter indicates that any environmental strain is able to cause corneal infection if the required conditions are met. Our study confirmed that fungal keratitis occurs in all age groups, though children tend to be less affected (2). In our case, only two of the 152 patients with fungal keratitis studied were under 18 years of age (data not shown). In general, fungal keratitis is more common in males than in females. This is probably because males are more associated with extensive outdoor activity, which involves a greater exposure to foreign bodies (2). Males were also predominant in this study.

O'Donnell (11), by using multilocus sequence data, had already demonstrated a high genetic diversity of F. solani and indicated that this taxon is indeed a species complex that contains at least 26 phylogenetically distinct species. Further studies are needed on the phylogenetic species placement of these isolates and whether keratitis may be linked to a particular phylogenetic group within such a complex.

ERIC-PCR, a technique commonly used for typing bacteria but also occasionally used for fungi (1, 7, 8), was more discriminatory than PCR-RFLP. It was also faster and easier to perform. However, the combination of the two techniques provided the most conclusive results. When only the first technique was used, it was shown that two isolates recovered from the same patient (patient 8) 2 days apart were genetically different (39E and 18E). This technique also showed that two isolates collected 8 months apart that had infected two patients (29 and 30) from two very distant regions (Itaquaquece and São Paulo) shared the same genotype (7E). Apart from these exceptions, comparatively, the epidemiologically related and unrelated isolates were best discriminated by the ERIC-PCR technique. This technique effectively distinguished between closely related isolates that may be indistinguishable by the other method. PCR-RFLP recognized significantly fewer genotypes, i.e., less than half of those recognized when ERIC-PCR was used. Combining the results of these two techniques showed that the isolates that infected patients 29 and 30 had different genotypes and confirmed that all of the isolates from the same patient yielded the same genotype. The only exceptions were the isolates that infected patient 8, which were also very different by PCR-RFLP (approximately 80% similarity). The fact that a patient was infected with two genotypes is very interesting. This can be a big problem for clinicians because it is not easy to be aware of a dual infection and since the two isolates can have different antifungal susceptibilities, its outcome can be complicated. Although mixed fusarial infections can be considered extremely rare, they have occasionally been detected. A case of a mixed infection by two species of Fusarium in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient also from Brazil was previously reported (4). In that case, the presence of both species was recognized by a morphological study. In the present case, morphological techniques alone were not enough to detect this mixed infection because both isolates were morphologically very similar.

Although many fungal species have been referenced in a recent comprehensive review of fungal ocular infections (12), this study has also shown that several rare fungi usually found as laboratory contaminants are able to cause keratitis. Laboratory isolates from clinical material should therefore be considered on an individual basis, and as they may be of clinical importance, they cannot be disregarded as contaminants (15). Clinicians should also be aware, as we have demonstrated here, that two different strains of the same species can infect the same eye concomitantly, especially if they belong to ubiquitous genera such as Aspergillus, Candida, or Fusarium. More than one colony should be collected from cultures derived from corneal samples, even if they are morphologically similar, to type them (if possible) and to avoid problems with treatment when multiple strains with different antifungal susceptibilities are present.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias from the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo of Spain (PI 020114). The senior author (P. G.) acknowledges research funds from ISHAM and Conselho National de Desenvolvimiento Cientifico e Tecnologico (CNPq) of Brazil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bart-Delabesse, E., J. Sarfati, J. P. Debeaupuis, W. van Leeuwen, A. van Belkum, S. Bretagne, and J. P. Latge. 2001. Comparison of restriction fragment length polymorphism, microsatellite length polymorphism, and random amplification of polymorphic DNA analyses for fingerprinting Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2683-2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrens-Baumann, W. 1999. Mycosis of the eye and its adnexa, p. 201. In W. Behrens-Baumann (ed.), Developments in ophthalmology, vol. 32. Karger, Basel, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Hoog, G. S., J. Guarro, J. Gené, and M. J. Figueras. 2000. Atlas of clinical fungi, p. 1126. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- 4.Guarro, J., M. Nucci, T. Akiti, and J. Gené. 2000. Mixed infection caused by two species of Fusarium in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3460-3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarro, J., C. Rubio, J. Gené, J. Cano, J. Gil, R. Benito, M. J. Moranderia, and E. Míguez. 2003. Case of keratitis caused by an uncommon Fusarium species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5823-5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guarro, J., L. A. Vieira, D. de Freitas, J. Gené, L. Zaror, A. L. Hofling-Lima, O. Fischman, C. Zorat-Yu, and M. J. Figueras. 2000. Phaeoisaria clematidis as a cause of keratomycosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2434-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leenders, A. C. A. P., A. van Belkum, M. Behrendt, A. Luijendijk, and H. A. Verbrugh. 1999. Density and molecular epidemiology of Aspergillus in air and relationship to outbreaks of Aspergillus infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1752-1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta, Y. R., A. Mehta, and Y. B. Rosato. 2002. ERIC and REP-PCR banding patterns and sequence. Analysis of the internal transcribed spacer of rDNA of Stemphylium solani isolates from cotton. Curr. Microbiol. 44:323-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mino de Kaspar, H., G. Zoulek, M. E. Paredes, R. Alborno, D. Medina, M. Centurion de Morinigo, M. Ortiz de Fresco, and F. Aguero. 1991. Mycotic keratitis in Paraguay. Mycoses 34:251-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Donnell, K. 1993. Fusarium and its near relatives, p 225-233. In D. R. Reynolds and J. W. Taylor (ed.), The fungal holomorph: mitotic, meiotic and pleomorphic speciation in fungal systenatics. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 11.O'Donnell, K. 2000. Molecular phylogeny of the Nectria haematococca-Fusarium solani species complex. Mycologia 92:919-938. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas, P. A. 2003. Current perspectives on ophthalmic mycoses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:730-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Versalovic, J., T. Koeuth, and J. R. Lupski. 1991. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6823-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinuesa, P., J. L. W. Redemaker, F. J. Bruijn, and D. Werner. 1998. Genotypic characterization of Bradyrhizobium strains nodulating endemic woody legumes of the Canary Islands by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA (16S rDNA) and 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacers, repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR genomic fingerprinting, and partial 16S rDNA sequencing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2096-2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vismer, H. F., W. F. O. Marasas, J. P. Rheeder, and J. J. Joubert. 2002. Fusarium dimerum as a cause of human eye infection. Med. Mycol. 40:399-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White, T. J., T. Bruns, S. Lee, and J. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, p. 315-322. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Geldfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols: a guide to the methods and applications. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 17.Zapater, R. C. 1986. Opportunistic fungus infections. Fusarium infections (keratomycosis by Fusarium). Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 27:68-69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zapater, R. C., and A. Arrechea. 1975. Mycotic keratitis by Fusarium. A review and report of two cases. Ophthalmologica (Basel) 170:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]