Abstract

Background

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) seriously affects the quality of life of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) as well as the response rate to chemotherapy. Acupuncture has a potential role in the treatment of CIPN, but at present there have been no randomized clinical research studies to analyze the effectiveness of acupuncture for the treatment of CIPN, particularly in MM patients.

Methods

The MM patients (104 individuals) who met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned into a solely methylcobalamin therapy group (500 μg intramuscular methylcobalamin injections every other day for 20 days; ten injections) followed by 2 months of 500 μg oral methylcobalamin administration, three times per day) and an acupuncture combined with methylcobalamin (Met + Acu) group (methylcobalamin used the same way as above accompanied by three cycles of acupuncture). Of the patients, 98 out of 104 completed the treatment and follow-ups. There were 49 patients in each group. The evaluating parameters included the visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/Gynecologic Oncology Group-Neurotoxicity (Fact/GOG-Ntx) questionnaire scores, and electromyographic (EMG) nerve conduction velocity (NCV) determinations. We evaluated the changes of the parameters in each group before and after the therapies and made a comparison between the two groups.

Results

After 84 days (three cycles) of therapy, the pain was significantly alleviated in both groups, with a significantly higher decrease in the acupuncture treated group (P < 0.01). The patients’ daily activity evaluated by Fact/GOG-Ntx questionnaires significantly improved in the Met + Acu group (P < 0.001). The NCV in the Met + Acu group improved significantly while amelioration in the control group was not observed.

Conclusions

The present study suggests that acupuncture combined with methylcobalamin in the treatment of CIPN showed a better outcome than methylcobalamin administration alone.

Trial registration

China Clinical Trials Register (registration no. ChiCTR-INR-16009079, registration date August 24, 2016).

Keywords: Acupuncture, CIPN, Methylcobalamin, Multiple myeloma

Background

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a common hematologic malignancy and the incidence rate increases every year worldwide. Proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib are commonly used for the initial treatment, as well as consolidation and maintenance therapies [1, 2]. However, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) during MM treatments is a dose-limiting side effect and the incidence rate of bortezomib-related neuropathy has been reported to be 30–60% [3, 4]. Common peripheral neuropathy symptoms in the distal limbs are symmetric sensory dysfunctions, with a variety of sensory losses such as glove or sock-shaped distribution, possibly associated with paresthesia and excessive pain. Other symptoms are movement disorders such as muscle weakness, muscle atrophy, diminished or disappeared limb and tendon reflexes, inability to fasten buttons as well as walking difficulties. In addition, autonomic nervous system disorders such as orthostatic hypotension, arrhythmia, bradycardia and other symptoms may occur.

Peripheral neuropathy is a key factor for drug dose and application duration restrictions, because patients often cannot tolerate symptoms, leading to a reduced drug dose and number of therapy cycles or even discontinuation of therapy. Therefore, reducing CIPN in MM treatments is a critical point for improving a patient’s quality of life and treatment outcome.

The therapy choices for CIPN treatments in MM patients are very limited but include neurotrophic drug treatment with methylcobalamin administered orally or as an intramuscular injection. The methylation of a functional group in methylcobalamin, a coenzyme of vitamin b12, enables drug availability and thereby promotes the metabolism of nucleic acids, proteins and lipids in nerve tissues. In addition, methylcobalamin stimulates cell lecithin synthesis, repairs damaged myelin and thereby improves nerve conduction velocity. First line treatments of neuropathic pain includes gabapentin, 5% lidocaine patches and opioid analgesics such as tramadol hydrochloride. Second line drugs include lamotrigine, carbamazepine and amitriptyline, as well as other antidepressants [5]. These drugs have various side effects, such as sedation, ataxia, dizziness, double vision, nausea and indigestion. The commonly used analgesics against neuropathic pain may work, but viable treatment options often do not completely relieve the symptoms.

However, when grades III-IV neurotoxicity occurs, the neurological symptoms will be partially relieved once the chemotherapy drug doses or therapy cycles are reduced, but inevitably the therapeutic effect on MM is also diminished.

Acupuncture, first mentioned in the 5th century BC, is part of traditional Chinese medicine and its effects, especially in pain control, have been confirmed in clinical trials, which led to the usage of acupuncture also in many other countries. A questionnaire of 180 patients with peripheral neuropathy showed that 30% of them choose acupuncture as an alternative method of pain control [6].

Studies on humans and animals have identified the neurochemical basis of acupuncture effects on brain functions. Acupuncture can stimulate receptors or cause the regular discharge of nerve fibers, leading to peripheral and central nervous system activation, resulting in the release of a variety of neurotransmitters [7]. The specific effect of acupuncture depends on the acupuncture point choice, the form of stimulation and the duration of the therapy [8]. Chinese acupuncture, an adjunct therapy, has gained increased attention in the medical field at home and abroad in recent years. Prospective clinical trials have demonstrated that acupuncture was effective in treating pain caused by diabetes as well as HIV virus infections [9–17], and various clinical trials have shown the effect of acupuncture in alleviating neuropathic pain in cancer patients [18, 19]. In addition, a case series has proven the efficacy of body acupuncture in treating patients with CIPN [20], and a pilot study demonstrated that acupuncture improved nerve conduction in peripheral neuropathy [21]. In recent studies, statistically and clinically significant reductions in subjective measurements of bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy (BIPN) were observed after acupuncture treatment [22, 23]. However, to date, there have been no randomized controlled clinical research to analyze the effectiveness of acupuncture in treating CIPN of MM patients.

Since previous research showed that acupuncture had good treatment effects on peripheral neuropathy of diabetes and HIV/AIDS patients, we hypothesized that acupuncture treatment of MM CIPN will also have positive therapeutic effects.

Methods

Patients

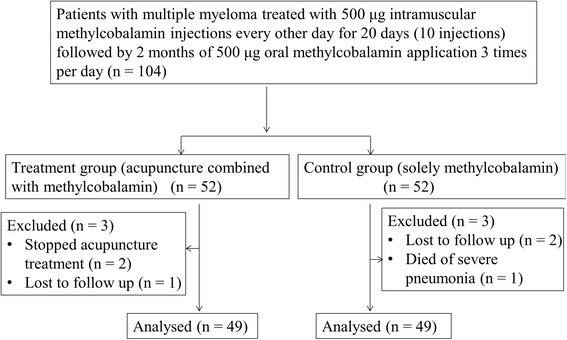

Four hundred twelve patients diagnosed with MM (not limited to the type or stage) were hospitalized for chemotherapy in our center between May 2010 and May 2014. The inclusion criteria were: diagnosed MM; baseline without peripheral neuropathy and peripheral neuropathy appeared after chemotherapy at grade II or above (according to the NCI CTCAE version 3.0 neuropathy severity assessment) [24]; EMG examinations showing disturbances in median and peroneal nerve conduction; platelet count greater than 30 × 109/L; no history of methylcobalamin allergy; having discontinued chemotherapy within 3 months and were willing to accept new therapy and sign an informed consent form. The exclusion criteria were: pregnancy; severe heart, liver or kidney dysfunction or other severe diseases (e.g. malignancies); neuropathy caused by tumor compression, nutritional disorders or infections or causes other than chemotherapy; refusal to sign the informed consent form. The remaining 104 MM patients who met the inclusion criteria in our center were randomly divided into two groups. 98 out of 104 completed the treatment and follow-up. In the Met + Acu group, two patients stopped acupuncture treatment because of scheduled stem cell transplantation and one patient was lost to follow up. In the control group, two patients were lost to follow up and one patient died of severe pneumonia. Finally, 49 patients who were treated with acupuncture combined with methylcobalamin (Met + Acu group) and 49 patients only treated with methylcobalamin (control group) were included for the outcome analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the present study

Treatments

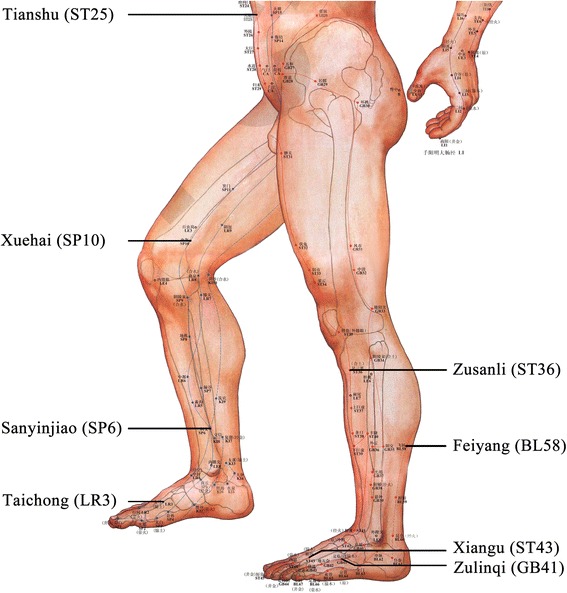

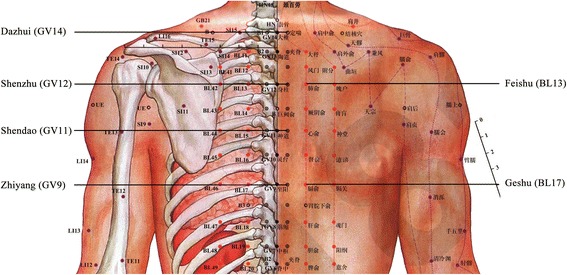

The control group received only 500 μg methylcobalamin intramuscularly every other day, 10 times and thereafter 500 μg orally three times a day. The Met + Acu group received the same methylcobalamin application with an additional acupuncture protocol according to the neurohumoral mechanism theory of acupuncture [25]. In all cases, the acupuncture was performed by the same senior physician who had acupuncture experience for 15 years. Every patient received needles bilaterally in the following acupoints: Supine position: bilateral Taichong (LR3), Xiangu (ST43), Zulinqi (GB41), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36), Xuehai (SP10), Tianshu (ST25); Prone position: Dazhui (GV14), Shenzhu (GV12), Shendao (GV11), Zhiyang (GV9), Feishu (BL13), Geshu (BL17) and Feiyang (BL58) (Figs. 2 and 3). The first acupuncture was in prone position acupoints with needle retention, followed by supine position acupoints. An aseptic procedure was executed with disposable, stainless steel 30–32 gauge needles, which were implanted to a depth of 0.3–1.0 in. into the acupoints until the patient felt dull pain or de qi [26], and were left in place for 30 min. The acupunctures were done daily for 3 days, then once every alternate day for 10 days as a treatment cycle. Each cycle was repeated every 28 days and the complete treatment included three cycles.

Fig. 2.

Scheme of acupuncture points on the legs, feet and ventral upper body

Fig. 3.

Scheme of acupuncture points on the dorsal upper body

Evaluation standards

The validated Ntx extension of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/Gynaecologic Oncology Group/Neurotoxicity (FACT/GOG-Ntx) questionnaire [27] was used to investigate the patients’ daily activities and evaluate the degree of neuropathy. The questionnaire included 7 questions about physical well-being, 7 questions about social/family well-being, 6 questions about emotional well-being, 7 questions about functional well-being and 9 questions about additional concerns. The VAS pain score [28] was used to assess neuralgia. The bilateral NCV of the arms and legs was determined by the same professional technician before and after treatment using Nicolet Viasys Viking Select EMG NCS equipment from the USA. Skin surface electrodes were used to record the average of the motor conduction velocities (MCV) of the bilateral median and peroneal nerves as well as sensory nerve conduction velocities (SCV) of the bilateral median and the sural nerves. All evaluation measurements were carried out before and after treatments.

CIPN severity assessment

CIPN was categorized according to the grading system published by Postma and Heimans (2000) [29].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad. Prism 5.01 statistical software. Assuming a mean value of the VAS score change was 2, standard deviation was 0.5 before and after treatment in the Met + Acu group, while the mean value of the VAS score change was 1.6; the standard deviation was 0 in the control group. A sample size of 41 in each group was considered to provide 95% power for detecting significant differences in the two groups (two-sided, α = 5%). To account for a 20% dropout, 104 patients in total (52 in each group) were included. The results are shown as the mean ± SEM. Between the two groups, single-factor analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) and Tukey’s test were used for analyses while an independent sample t-test was used in one group. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Results

The characteristics of the treatment and control groups are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups regarding the baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the MM patients

| Characteristic | Met + Acu Group (n = 49) | Control Group (n = 49) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 27 | 29* |

| Female | 22 | 20* |

| Age (average) | 62.46 | 65.29* |

| Type | ||

| IgG | 25 | 21* |

| IgA | 13 | 14* |

| IgD | 2 | 3* |

| Light chain (Kappa/lambda) | 9 | 11* |

| PN Grade (CTCAE) | ||

| Grade 2 | 20 | 19* |

| Grade 3 | 25 | 27* |

| Grade 4 | 4 | 3* |

| VAS scores | 5.57 ± 0.26 | 5.50 ± 0.24* |

| FACT/the GOG-Ntx scores | 36.48 ± 0.47 | 36.63 ± 0.55* |

* P > 0.05, compared between the Met + Acu and control groups before therapy

VAS pain scores

After 3 cycles of therapy, the pain was significantly mitigated in the Met + Acu group, while the VAS pain scores decreased in 85.7% of the patients (42/49). Pain in the control group was also eased and the VAS pain scores decreased in 77.6% of these patients (38/49). However, the VAS pain scores in the Met + Acu group decreased more significantly compared to the control group (P < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

VAS pain scores before and after treatment

| Group | n | Before therapy | After therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Met + Acu Group | 49 | 5.57 ± 0.257 | 3.23 ± 0.170*** △△ |

| Control Group | 49 | 5.50 ± 0.244 | 4.25 ± 0.197*** |

*** P < 0.001, compared before and after therapy

△△ P < 0.01, compared between the Met + Acu and control groups

Quality of life scores

Evaluated by FACT/the GOG-Ntx questionnaire scores, the nervous system symptoms improved significantly in the Met + Acu group (P < 0.001) after therapy, but not in the control group (P > 0.05), and the improvement was more significant in the Met + Acu group (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

FACT/the GOG-Ntx questionnaire scores before and after treatment

| Group | n | Before therapy | After therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Met + Acu Group | 49 | 36.48 ± 0.470 | 32.98 ± 0.542*** △ |

| Control Group | 49 | 36.63 ± 0.551 | 35.17 ± 0.518 |

*** P < 0.001, compared before and after therapy

△ P < 0.05, compared between the Met + Acu and control groups

Nerve conduction velocity

After treatments, there was no significant difference in MCV improvement in the Met + Acu group compared to the control group (P > 0.05). In contrast, before and after treatment in the Met + Acu group, the MCV of the bilateral median and peroneal nerves improved significantly after the acupuncture therapy (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively), while there was no obvious change in the control group (P > 0.05). The SCV of the sural nerve in the Met + Acu group improved significantly (P < 0.01), but there was no obvious change in the bilateral median nerve after the Met + Acu therapy (P > 0.05) (Table 4). Changes in the SCV of the sural and median nerve in the control group were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Comparing the SCV after therapy between the two groups, the SCV of the sural nerve in the Met + Acu group was significantly superior to the control group (P < 0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Nerve conduction velocity before and after treatment

| Group | n | MCV | SCV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral median nerve | Peroneal nerve | Bilateral median nerve | Sural nerve | |||

| Met + Acu group | Before treatment | 49 | 49.81 ± 0.78 | 44.59 ± 0. 78 | 49.58 ± 0.73 | 43.99 ± 0.63 |

| After treatment | 49 | 52.84 ± 0.81* | 47.88 ± 0.67** | 51.51 ± 0.64 | 46.87 ± 0.77**△△ | |

| Control group | Before treatment | 49 | 50.43 ± 0.70 | 45.09 ± 0.71 | 49.98 ± 0.94 | 44.11 ± 0.60 |

| After treatment | 49 | 51.05 ± 0.60 | 45.42 ± 0.76 | 50.40 ± 0.79 | 43.61 ± 0.51 | |

* P < 0.05, compared before and after therapy

** P < 0.01, compared before and after therapy

△△ P < 0.01, compared between the Met + Acu and control groups

These data suggested that the treatment of Met + Acu improved the MCV and SCV (except for the median nerve SCV) in the Met + Acu group, while a solely methylcobalamin treatment in the control group had no effect on SCVs or MCVs.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized, controlled, prospective study on the use of acupuncture in the treatment of multiple myeloma patients with CIPN grades II–IV [29]. After 84 days (three cycles) of therapy, although methylcobalamin treatment alone was helpful in relieving pain and improving the quality of life, the study showed that acupuncture combined with methylcobalamin for the treatment of CIPN was significantly superior in providing pain relief (VAS pain scores) and life quality improvement (FACT/GOG-Ntx questionnaire scores). Our results are in agreement with previous reports that acupuncture has a beneficial effect on peripheral neuropathy and are consistent with the study of Schroder et al [21]; nerve conduction in the sural nerve was improved best in our study [20, 21]. The SCV of the median nerve did not change after a Met + Acu therapy, which might reflect the choice of acupuncture points, indicating that they have a major impact on the therapeutic effects [30].

According to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory, the symptoms of CIPN are caused by the body’s failure to direct Qi (vital energy) and blood to the four limbs, resulting in sensory symptoms and impaired limb function while acupuncture restores body Qi and blood, and directs their flow to the extremities [20], which is supported by a studies which demonstrated that acupuncture led to vasodilation and enhanced blood perfusion [31, 32].

It has been suggested, that bortezomib mainly affects the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) of the primary sensory neurons leading to disturbed transcription, nuclear processing and transport, as well as cytoplasmic translation of mRNAs and histopathological changes in the DRG neurons. In addition, neural survival is compromised due to inhibition of nerve growth factor (NGF) transcription [33] and a highly significant correlation between the decrease in circulating levels of NGF and the severity of CIPN has been reported (P < 0.001) [34].

Previous animal studies noted that both protein and mRNA levels of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and GDNF family receptor alpha-1 (GFRalpha-1) were upregulated in the DRGs after acupuncture [35].

However, another recent study found that acupuncture significantly changed the expression of 17 hypothalamic proteins in a rat neuropathic pain model [36]. Taken together, though enhanced blood perfusion as result of acupuncture has been proven in humans, other mechanisms of specific gene expression changes have so far only been investigated in animal models. It is also unclear whether acupuncture leads to histological changes, which might be evaluated in future studies with biopsy-analyses [21]. In addition, since the acupoints were established in TCM several centuries ago, analysis of acupoints with advanced techniques like MRI may lead to improved results.

There were no obvious unexpected side effects during the treatments of both groups, and puncture site infections or bleeding did not occur during the acupuncture process, suggesting that acupuncture is a safe treatment for CIPN in MM patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study revealed, in agreement with previous pilot studies, that acupuncture for the treatment of CIPN as adjunct therapy leads to a significantly improved outcome in MM patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was financially supported by grants from the Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang Province, Program Number: 2010ZA057, 2014ZB060; the Science and Technology Project of the Health Department of Zhejiang Province, Program Number: 2013KYA071; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Program Number: 81471532, 81402353.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

XYH and ZC designed the study. XYH performed the study and statistical analysis, XYH and LJW assessed the efficacy and wrote the manuscript, HFS was responsible for acupuncture, GFZ, JSH, WJW, GQW, JMS, WYZ, JS, HH and ZC recruited and managed the patients. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University and informed written consent was obtained from all of the patients before their participation in the study.

Abbreviations

- CIPN

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy

- EMG

Electromyography

- MCV

Motor conduction velocity

- Met + Acu

Methylcobalamin + acupuncture

- MM

Multiple myeloma

- NCV

Nerve conduction velocity

- SCV

Sensory conduction velocity

- VAS

Visual analogue scale

Contributor Information

Xiaoyan Han, Email: yanwei3525@126.com.

Lijuan Wang, Email: wanglj730@163.com.

Hongfei Shi, Email: shf499@163.com.

Gaofeng Zheng, Email: gougoubababa@163.com.

Jingsong He, Email: hjs2005@263.net.

Wenjun Wu, Email: wenjun96@163.com.

Jimin Shi, Email: jiminshi@126.com.

Guoqing Wei, Email: weiguoqing2000@sina.com.

Weiyan Zheng, Email: zhengwy2006@live.cn.

Jie Sun, Email: jsun1492@zju.edu.cn.

He Huang, Email: hehuangyu@126.com.

Zhen Cai, Phone: +86-571-56734727, Email: caiz@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Moreau P, Richardson PG, Cavo M, Orlowski RZ, San Miguel JF, Palumbo A, et al. Proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma: 10 years later. Blood. 2012;120(5):947–59. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-403733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chauhan D, Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Richardson P, Anderson KC. Proteasome inhibitor therapy in multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(4):686–92. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bang SM, Lee JH, Yoon SS, Park S, Min CK, Kim CC, et al. A multicenter retrospective analysis of adverse events in Korean patients using bortezomib for multiple myeloma. Int J Hematol. 2006;83(4):309–13. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.A30512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson PG, Briemberg H, Jagannath S, Wen PY, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. Frequency, characteristics, and reversibility of peripheral neuropathy during treatment of advanced multiple myeloma with bortezomib. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(19):3113–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Y, Garcia MK, Chang DZ, Chiang J, Lu J, Yi Q, et al. Multiple myeloma, painful neuropathy, acupuncture? Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(3):319–25. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318173a520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunelli B, Gorson KC. The use of complementary and alternative medicines by patients with peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 2004;218(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulett GA, Han J, Han S. Traditional and evidence-based acupuncture: history, mechanisms, and present status. South Med J. 1998;91(12):1115–20. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donald GK, Tobin I, Stringer J. Evaluation of acupuncture in the management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Acupunct Med. 2011;29(3):230–3. doi: 10.1136/acupmed.2011.010025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abuaisha BB, Costanzi JB, Boulton AJ. Acupuncture for the treatment of chronic painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy: a long-term study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;39(2):115–21. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(97)00123-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C, Ma YX, Yan Y. Clinical effects of acupuncture for diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Tradit Chin Med. 2010;30(1):13–4. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6272(10)60003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao JL, Li ZR. Clinical observation on mild-warm moxibustion for treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2008;28(1):13–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn AC, Bennani T, Freeman R, Hamdy O, Kaptchuk TJ. Two styles of acupuncture for treating painful diabetic neuropathy--a pilot randomised control trial. Acupunct Med. 2007;25(1–2):11–7. doi: 10.1136/aim.25.1-2.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao HL, Gao X, Gao YB. Clinical observation on effect of acupuncture in treating diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2007;27(4):312–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang H, Shi K, Li X, Zhou W, Cao Y. Clinical study on the wrist-ankle acupuncture treatment for 30 cases of diabetic peripheral neuritis. J Tradit Chin Med. 2006;26(1):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips KD, Skelton WD, Hand GA. Effect of acupuncture administered in a group setting on pain and subjective peripheral neuropathy in persons with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(3):449–55. doi: 10.1089/1075553041323678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galantino ML, Eke-Okoro ST, Findley TW, Condoluci D. Use of noninvasive electroacupuncture for the treatment of HIV-related peripheral neuropathy: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5(2):135–42. doi: 10.1089/acm.1999.5.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang YP, Ji L, Li JT, Pu JQ, Liu FJ. Effects of acupuncture on diabetic peripheral neuropathies. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2005;25(8):542–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minton O, Higginson IJ. Electroacupuncture as an adjunctive treatment to control neuropathic pain in patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(2):115–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alimi D, Rubino C, Pichard-Leandri E, Fermand-Brule S, Dubreuil-Lemaire ML, Hill C. Analgesic effect of auricular acupuncture for cancer pain: a randomized, blinded, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(22):4120–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong R, Sagar S. Acupuncture treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy--a case series. Acupunct Med. 2006;24(2):87–91. doi: 10.1136/aim.24.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schroder S, Liepert J, Remppis A, Greten JH. Acupuncture treatment improves nerve conduction in peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(3):276–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bao T, Goloubeva O, Pelser C, Porter N, Primrose J, Hester L, et al. A pilot study of acupuncture in treating bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with multiple myeloma. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):396–404. doi: 10.1177/1534735414534729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia MK, Cohen L, Guo Y, Zhou Y, You B, Chiang J, et al. Electroacupuncture for thalidomide/bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma: a feasibility study. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:41. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-7-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Rusch V, Jaques D, Budach V, et al. CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13(3):176–81. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng X. Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Beijing: Foreign Language Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong J, Gollub R, Huang T, Polich G, Napadow V, Hui K, et al. Acupuncture de qi, from qualitative history to quantitative measurement. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(10):1059–70. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang HQ, Brady MF, Cella D, Fleming G. Validation and reduction of FACT/GOG-Ntx subscale for platinum/paclitaxel-induced neurologic symptoms: a gynecologic oncology group study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17(2):387–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huskisson EC. Measurement of pain. Lancet. 1974;2(7889):1127–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)90884-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Postma TJ, Heimans JJ. Grading of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Ann Oncol. 2000;11(5):509–13. doi: 10.1023/A:1008345613594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang ZJ, Wang XM, McAlonan GM. Neural acupuncture unit: a new concept for interpreting effects and mechanisms of acupuncture. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:429412. doi: 10.1155/2012/429412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litscher G, Wang L, Huber E, Nilsson G. Changed skin blood perfusion in the fingertip following acupuncture needle introduction as evaluated by laser Doppler perfusion imaging. Lasers Med Sci. 2002;17(1):19–25. doi: 10.1007/s10103-002-8262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takayama S, Watanabe M, Kusuyama H, Nagase S, Seki T, Nakazawa T, et al. Evaluation of the effects of acupuncture on blood flow in humans with ultrasound color Doppler imaging. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:513638. doi: 10.1155/2012/513638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Argyriou AA, Bruna J, Marmiroli P, Cavaletti G. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity (CIPN): an update. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;82(1):51–77. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavaletti G, Bogliun G, Marzorati L, Zincone A, Piatti M, Colombo N, et al. Early predictors of peripheral neurotoxicity in cisplatin and paclitaxel combination chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(9):1439–42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dong ZQ, Ma F, Xie H, Wang YQ, Wu GC. Changes of expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor in dorsal root ganglions and spinal dorsal horn during electroacupuncture treatment in neuropathic pain rats. Neurosci Lett. 2005;376(2):143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao Y, Chen S, Xu Q, Yu K, Wang J, Qiao L, et al. Proteomic analysis of differential proteins related to anti-nociceptive effect of electroacupuncture in the hypothalamus following neuropathic pain in rats. Neurochem Res. 2013;38(7):1467–78. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.