Abstract

Pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 1b (PCH1b) is an autosomal recessive disorder that causes cerebellar hypoplasia and spinal motor neuron degeneration, leading to mortality in early childhood. PCH1b is caused by mutations in the RNA exosome subunit gene, EXOSC3. The RNA exosome is an evolutionarily conserved complex, consisting of nine different core subunits, and one or two 3′-5′ exoribonuclease subunits, that mediates several RNA degradation and processing steps. The goal of this study is to assess the functional consequences of the amino acid substitutions that have been identified in EXOSC3 in PCH1b patients. To analyze these EXOSC3 substitutions, we generated the corresponding amino acid substitutions in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ortholog of EXOSC3, Rrp40. We find that the rrp40 variants corresponding to EXOSC3-G31A and -D132A do not affect yeast function when expressed as the sole copy of the essential Rrp40 protein. In contrast, the rrp40-W195R variant, corresponding to EXOSC3-W238R in PCH1b patients, impacts cell growth and RNA exosome function when expressed as the sole copy of Rrp40. The rrp40-W195R protein is unstable, and does not associate efficiently with the RNA exosome in cells that also express wild-type Rrp40. Consistent with these findings in yeast, the levels of mouse EXOSC3 variants are reduced compared to wild-type EXOSC3 in a neuronal cell line. These data suggest that cells possess a mechanism for optimal assembly of functional RNA exosome complex that can discriminate between wild-type and variant exosome subunits. Budding yeast can therefore serve as a useful tool to understand the molecular defects in the RNA exosome caused by PCH1b-associated amino acid substitutions in EXOSC3, and potentially extending to disease-associated substitutions in other exosome subunits.

Keywords: pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 1b, RNA exosome, EXOSC3, Rrp40, EXOSC2, RNA processing/degradation

THE RNA exosome is an evolutionarily conserved ribonuclease complex that is responsible for several essential RNA processing and degradation steps (Mitchell et al. 1997; Allmang et al. 1999; Schneider and Tollervey 2013). Major exosome substrates include mRNA, rRNA, and small RNAs. In addition to degrading aberrant and unneeded transcripts, the RNA exosome also trims precursor RNAs, including 5.8S rRNA (Mitchell et al. 1996). The RNA exosome thus plays critical roles in both RNA degradation and maturation.

The subunits of the RNA exosome complex are evolutionarily conserved and many were first identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a screen for ribosomal RNA processing (rrp) mutants (Mitchell et al. 1996, 1997; Allmang et al. 1999). S. cerevisiae Rrp subunits correspond to human EXOSC subunits. The functions of the RNA exosome have been extensively characterized in budding yeast (Sloan et al. 2012), and many are conserved in humans (Schilders et al. 2005; Staals et al. 2010; Lubas et al. 2011, 2015). Within the RNA exosome, six subunits comprise a core ring, and three putative RNA-binding subunits, including EXOSC3, form a cap that interacts with the core ring on one side of the complex (Figure 1A). The catalytic DIS3 subunit, which possesses both endo and exoribonuclease activities (Dziembowski et al. 2007; Lebreton et al. 2008; Schaeffer et al. 2009), associates with the opposite side of the core ring from the cap (Figure 1A) (Malet et al. 2010; Staals et al. 2010; Tomecki et al. 2010; Makino et al. 2013). RNA substrates can be threaded through the central channel of the core ring from the EXOSC3/cap side (Liu et al. 2006; Bonneau et al. 2009; Malet et al. 2010; Makino et al. 2013). Additional RNA entry points have also been identified (Liu et al. 2014; Wasmuth et al. 2014; Han and van Hoof 2016) that could provide insight into how the RNA exosome balances precise processing and complete degradation of RNA.

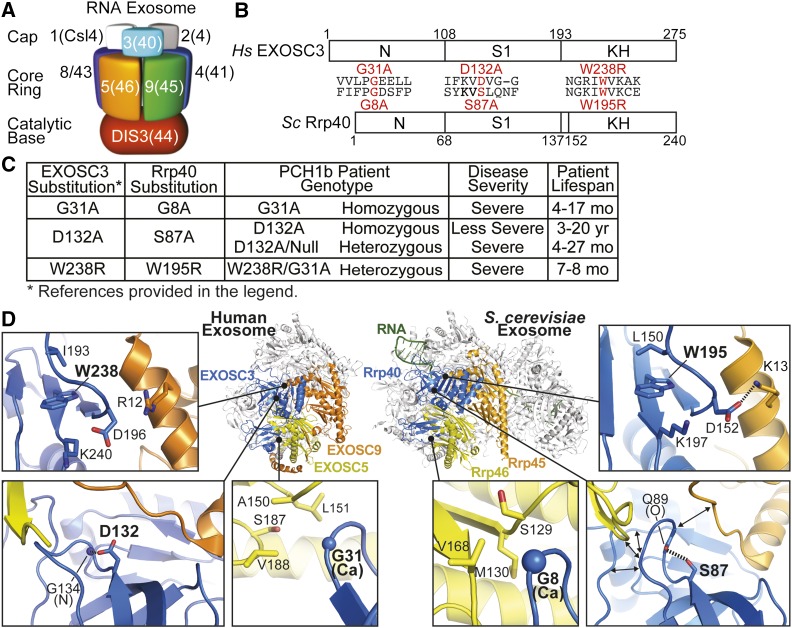

Figure 1.

Overview of PCH1b-associated amino acid substitutions in the human EXOSC3 subunit of the RNA exosome, and the corresponding substitutions in the budding yeast ortholog, Rrp40, examined in this study. (A) The RNA exosome is an evolutionarily conserved ribonuclease complex composed of 10 different subunits—three cap subunits: EXOSC1/Csl4 (Human/S. cerevisiae); EXOSC2/Rrp4; EXOSC3/Rrp40, six core subunits: EXOSC4/Rrp41; EXOSC5/Rrp46; EXOSC6/Mtr3; EXOSC7/Rrp42; EXOSC8/Rrp43; EXOSC9/Rrp45, and a catalytic base subunit: DIS3/Rrp44. Mutations in the EXOSC3 gene encoding a cap subunit [light blue, labeled with 3(40)] cause PCH1b (Wan et al. 2012), mutations in the EXOSC8 gene, encoding a core subunit [purple, labeled with 8(43)] cause PCH1c (Boczonadi et al. 2014), and mutations in the EXOSC2 gene, encoding a cap subunit [gray, labeled with 2(4)] cause a novel syndrome (Di Donato et al. 2016). (B) EXOSC3 and its budding yeast ortholog, Rrp40, contain three different domains: an N-terminal domain, a central S1 putative RNA binding domain, and a C-terminal putative RNA binding KH (K homology) domain. The position and flanking sequence of the major amino acid substitutions in PCH1b-associated human EXOSC3, and the substitutions generated in the S. cerevisiae ortholog of EXOSC3, Rrp40 (shown in red) are indicated. (C) Summary of the major amino acid substitutions identified in EXOSC3 in PCH1b patients (Wan et al. 2012) with corresponding substitutions in budding yeast Rrp40 generated in this study. Patient genotypes (Homozygous/Heterozygous) are reported, and disease severity and patient lifespans for each substitution (Wan et al. 2012; Schwabova et al. 2013; Eggens et al. 2014) are also presented to provide some context for the functional consequences of the different amino acid substitutions. (D) PCH1b-associated substitutions occur in EXOSC3 residues located near RNA exosome subunit interfaces. Structural models of the human RNA exosome (left) [PDB#2NN6 (Liu et al. 2006)] and S. cerevisiae RNA exosome (right) [PDB#4IFD; (Makino et al. 2013)] are depicted. The nine subunit human RNA exosome structure highlights the EXOSC3 (blue), EXOSC5 (yellow), and EXOSC9 (yellow) subunits. Zoomed-in views of three subunit interface regions show the locations of PCH1b-associated EXOSC3 substituted residues (G31, D132, and W238 residues in large, bold font). The S. cerevisiae RNA exosome structure highlights the orthologous Rrp40 (blue), Rrp46 (yellow), and Rrp45 (orange) subunits. Zoomed-in views show the locations of the evolutionarily conserved residues (G8, S87, and W195). S. cerevisiae Rrp40 G8 (EXOSC3 G31) is located in a hydrophobic pocket at an interface with Rrp46 (EXOSC5). Rrp40 S87 (EXOSC3 D132) and the backbone of Q89 are positioned to form a hydrogen bond that may organize the loop between strands β3 and β4, which is at the interface with both Rrp46 (EXOSC5) and Rrp45 (EXOSC9). Rrp40 W195 (EXOSC3 W238) sits in a large pocket, and could be important for positioning the loop of Rrp40 that forms an interface with Rrp45 (EXOSC5).

The RNA exosome is present in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA exosomes also require specific exosome cofactors (Butler and Mitchell 2010; Schaeffer et al. 2010), which help to guide the degradation and/or processing of specific RNAs. In particular, the cytoplasmic cofactor, the SKI complex, is required for all known cytoplasmic functions of the RNA exosome, but not for its nuclear functions (Jacobs Anderson and Parker 1998; van Hoof et al. 2000). Importantly, exosome cofactors characterized in budding yeast (Jacobs Anderson and Parker 1998; Allmang et al. 1999; Brown et al. 2000; van Hoof et al. 2000; LaCava et al. 2005; Vasiljeva and Buratowski 2006), are conserved in Metazoa, and possess conserved functions in humans (Schilders et al. 2007; Shcherbik et al. 2010; Lubas et al. 2011; Kowalinski et al. 2016).

Defects in the RNA exosome, and exosome cofactors, have been implicated in several genetic diseases. Mutations in SKI complex genes have been linked to tricho-hepato-enteric (THE) syndrome, which causes intestinal failure (Hartley et al. 2010; Fabre et al. 2012, 2013). In addition, mutations in the DIS3 catalytic subunit gene have been implicated in multiple myeloma (Chapman et al. 2011; Tomecki et al. 2013; Robinson et al. 2015). Recently, mutations in genes encoding structural exosome subunits have been linked to neurological diseases (Wan et al. 2012; Boczonadi et al. 2014; Di Donato et al. 2016). Mutations in the gene encoding the RNA exosome cap subunit, EXOSC3 (Figure 1, B and C), have been linked to pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 1b (PCH1b) (Wan et al. 2012). PCH1b does not appear to share common traits with THE syndrome or multiple myeloma. Instead, PCH1b patients exhibit significant atrophy of the pons and cerebellum, Purkinje cell abnormalities, and degeneration of spinal motor neurons (Wan et al. 2012). PCH1b patients also show microcephaly, muscle atrophy, and growth and developmental retardation (Rudnik-Schoneborn et al. 2013). Most PCH1b patients do not live past childhood. Elucidation of the molecular mechanisms that underlie PCH1b is therefore of critical importance for the development of new treatments.

Pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH) is a group of recessive, autosomal disorders caused by mutations in several genes. Like PCH1b, PCH1c is caused by mutations in a gene encoding an RNA exosome core subunit, EXOSC8 (Boczonadi et al. 2014) (Figure 1A). However, most PCH subtypes are caused by mutations in genes encoding tRNA splicing endonuclease subunits that function in tRNA processing (PCH2a, 2b, 2c, 4, 5, and 10) (Budde et al. 2008; Namavar et al. 2011; Hanada et al. 2013; Schaffer et al. 2014), a selenocysteinyl tRNA charging enzyme (PCH2d) (Agamy et al. 2010) or a mitochondrial arginyl-tRNA synthetase (PCH6) (Edvardson et al. 2007). A few PCH subtypes are caused by mutations that have no apparent link to the RNA exosome or tRNA, such as in genes encoding vaccinia-related kinase (PCH1a) (Renbaum et al. 2009), chromatin modifying protein 1A (PCH8) (Akizu et al. 2013), and adenosine monophosphate deaminase 2 (PCH9) (Mochida et al. 2012). Understanding how these disparate gene mutations cause PCH diseases with common traits requires study of the functional defects that lead to disease.

Currently, it is unclear how the amino acid substitutions in EXOSC3 contribute to PCH1b disease, but it is unlikely that PCH1b is caused by complete inactivation of the RNA exosome as this complex is essential even in budding yeast (Mitchell et al. 1997). EXOSC3 amino acid substitutions may cause PCH1b by several potential mechanisms. First, EXOSC3 changes could affect a subset of RNA exosome functions. In yeast, mutations in another RNA exosome cap subunit gene, CSL4, disrupt some, but not other, functions of the RNA exosome (van Hoof et al. 2000). Second, EXOSC3 amino acid changes could affect RNA exosome-mediated degradation of tRNAs. The yeast RNA exosome degrades tRNAs (Wichtowska et al. 2013) and misprocessed precursors of initiator tRNAs (Kadaba et al. 2004). Third, EXOSC3 changes could reduce total RNA exosome activity. Finally, EXOSC3 changes could impair functions of EXOSC3 that are independent of the RNA exosome. This last mechanism seems less likely, as mutations in another exosome subunit gene, EXOSC8, cause PCH1c disease (Boczonadi et al. 2014).

To begin to address the molecular defects that underlie PCH1b disease, we have generated and analyzed amino acid substitutions in the budding yeast ortholog of EXOSC3, Rrp40, corresponding to substitutions in PCH1b patients. Unlike most rrp40 variants analyzed, which do not exhibit any discernable phenotypes in yeast, the rrp40-W195R variant, corresponding to EXOSC3-W238R in PCH1b, affects cell growth and RNA exosome function as the sole cellular copy. Moreover, the rrp40-W195R protein is unstable and does not associate efficiently with the RNA exosome in the presence of wild-type Rrp40. Mouse EXOSC3 variant levels are also reduced relative to wild-type EXOSC3 in a neuronal cell line. These results suggest a model for RNA exosome assembly that involves discrimination between wild-type and variant exosome subunits.

Materials and Methods

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains, plasmids, and chemicals

All DNA manipulations were performed according to standard methods (Sambrook et al. 1989), and all media were prepared by standard procedures (Adams et al. 1997). All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), United States Biological (Swampscott, MA), or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), unless otherwise noted. All S. cerevisiae strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplemental Material, Table S1. The rrp40∆ strain yAV1107 and rrp4Δ strain yAV1104 were previously described (Schaeffer et al. 2009), as was the ski7∆ strain yAV571 (van Hoof et al. 2000). The RRP40-TAP strain was obtained from GE Dharmacon. The wild-type strain MHY501, and doa3-1 strain MHY3646, were previously described (Chen and Hochstrasser 1996; Li et al. 2007).

The LEU2CEN6RRP40-Myc (pAC3161) plasmid was constructed by PCR amplification of the RRP40 promoter, 5′-UTR, and ORF from RRP40 genomic DNA plasmid (pAC3016), cloning into pRS425 plasmid (Sikorski and Hieter 1989) containing C-terminal 2xMyc tag and ADH1 terminator, and PCR amplification and cloning of RRP40-2xMyc-ADH1 into pRS315. The LEU2CEN6rrp40-G8A-Myc (pAC3162), rrp40-S87A-Myc (pAC3257), rrp40-W195A-Myc (pAC3163), rrp40-W195R-Myc (pAC3259), and rrp40-W195F-Myc (pAC3286) mutant plasmids were generated with rrp40 oligonucleotides encoding amino acid substitutions, RRP40-Myc (pAC3161) plasmid template, and QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). The LEU2CEN6RRP4 (pAV991) plasmid was constructed by PCR amplification of the RRP4 from S. cerevisiae genomic DNA, and cloning into pRS415 plasmid (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). The LEU2CEN6rrp4-G8A (pAV1181) and rrp4-G226D (pAV1183) mutant plasmids were generated with rrp4 oligonucleotides encoding amino acid substitutions, RRP4 (pAV991) plasmid template, and QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). The pAV188 his3-nonstop reporter plasmid was previously described (van Hoof et al. 2002).

The LEU2RRP40-Myc and rrp40-Myc mutant plasmids were transformed into the rrp40∆ strain yAV1107, selected on Ura− Leu− plates, and grown on 5-FOA Leu− plates to select for rrp40∆ cells that lack the URA3RRP40 plasmid, and contain only the LEU2RRP40-Myc or rrp40-Myc plasmid. The LEU2RRP40-Myc and rrp40-Myc plasmids were transformed into RRP40-TAP, wild-type MHY501, and doa3-1 MHY3646 strains, and selected on Leu− plates. The LEU2RRP4 and rrp4 mutant plasmids were transformed into the rrp4∆ strain yAV1104, selected on Ura− Leu− plates, and grown on 5-FOA Leu− plates to select for rrp4∆ cells that lack the URA3RRP4 plasmid, and contain only the LEU2RRP4 or rrp4 plasmid (File S1).

The Myc-Exosc3 (pAC3417) plasmid was constructed by PCR amplification of murine Exosc3 ORF (GenBank accession number NM_025513.3) using oligonucleotides (the 5′-primer encoding an N-terminal 2xMyc tag), and mouse cDNA from N2a cells, and cloning into pIGneo (Addgene) plasmid. The Myc-Exosc3G31A (pAC3418) and Myc-Exosc3W237R (pAC3420) mutant plasmids were generated with Exosc3 oligonucleotides encoding amino acid substitutions, Myc-Exosc3 (pAC3417) plasmid template, and QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). All constructs were sequenced to ensure the presence of each desired mutation, and the absence of any additional mutations.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae growth assays

To test the in vivo function of rrp40 mutants, rrp40∆ cells containing RRP40-Myc or rrp40-Myc mutant plasmid were serially diluted, spotted, and grown on solid medium plates, or grown in liquid medium and measured by recording optical density over time in a microplate reader. The in vivo function of rrp4 mutants was tested in similar growth assays, using rrp4∆ cells containing RRP4 or rrp4 mutant plasmid. For growth on solid media, rrp40∆ (yAV1107) cells containing only RRP40-Myc (pAC3161), rrp40-G8A-Myc (pAC3162), rrp40-S87A-Myc (pAC3257), rrp40-W195R-Myc (pAC3259), rrp40-W195A-Myc (pAC3163) or rrp40-W195F-Myc (pAC3286), or rrp4∆ (yAV1104) cells containing only RRP4 (pAV991), rrp4-G58V (pAV1181) or rrp4-G226D (pAV1183) plasmid were grown overnight at 30° to saturation in Leu− minimal medium. Cell concentrations were normalized to OD600 = 1, serially diluted in 10-fold dilutions, spotted on Leu− minimal media plates, or Leu− minimal media plates containing 25 µM 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and grown at 25, 30, and 37°. Plates were imaged after 1 and 2 days of growth. In the plasmid shuffle assay, rrp40∆ (yAV1107) cells containing RRP40URA3 maintenance plasmid and vector (pRS315), RRP40-Myc (pAC3161) or rrp40-Myc (pAC3161-3163, pAC3257, pAC3259, and pAC3286) were grown overnight at 30° to saturation in Ura− Leu− minimal medium. Cell concentrations were normalized and serially diluted, as before, and spotted on Ura− Leu− minimal medium plates, or Leu− minimal medium plates containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA), and grown at 25, 30, and 37°. For growth in liquid media, rrp40∆ cells (yAV1107) containing only RRP40-Myc or rrp40-Myc mutant plasmid or rrp4 (yAV1104) containing only RRP4 or rrp4 mutant plasmid were grown overnight at 30° to saturation in Leu− minimal medium, diluted to an OD600 = 0.01 in Leu− minimal media in a 24-well plate, and growth at 37° for RRP40/rrp40 cells, or 30° for RRP4/rrp4 cells, was monitored and recorded at OD600 in a BioTek SynergyMx microplate reader with Gen5 v2.04 software over 24 hr. Technical triplicates of each strain were measured, and the average of these triplicates was calculated and graphed.

His3-nonstop growth assay

The His3-nonstop growth assay was performed as previously described (Schaeffer et al. 2008). rrp40∆ cells (yAV1107) containing RRP40-Myc (pAC3161), rrp40-G8A-Myc (pAC3162), rrp40-S87A-Myc (pAC3257), rrp40-W195A-Myc (pAC3163), or rrp40-W195R-Myc (pAC3259) plasmid and his3-nonstop (pAV188) plasmid (van Hoof et al. 2002), encoding a His3-nonstop reporter, were serially diluted and spotted onto Ura− and Ura− His− minimal medium plates and grown at 37°. As a control, ski7Δ (yAV571) cells containing his3-nonstop plasmid (pAV188) were also assayed for growth on Ura− and Ura− His− minimal medium plates.

Total RNA isolation

To prepare S. cerevisiae total RNA from cell pellets of 10 ml cultures grown to OD600 = 0.5–0.8, cell pellets in 2 ml screw-cap tubes were resuspended in 1 ml TRIzol (Invitrogen), 300 µl glass beads were added, and cell samples were disrupted in Mini Bead Beater 16 Cell Disrupter (Biospec) for 2 min at 25°. For each sample, 100 µl of 1-bromo-3-chloropropane (BCP) was added, the sample was vortexed for 15 sec, and incubated at 25° for 2 min. Sample was centrifuged at 16,300 × g for 8 min at 4°, and the upper layer was transferred to a fresh microfuge tube. RNA was precipitated with 500 µl isopropanol, and the sample was vortexed for 10 sec to mix. Total RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 16,300 × g for 8 min at 4°. RNA pellet was washed with 1 ml of 75% ethanol, centrifuged at 16,300 × g for 5 min at 4°, and air-dried for 15 min. Total RNA was resuspended in 50 µl diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC, Sigma)-treated water, and stored at −80°.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For analysis of NEL025c CUT, U4 snRNA, and ITS-2 rRNA levels in rrp40 mutant cells, rrp40∆ (yAV1107) cells containing RRP40-Myc (pAC3161), rrp40-G8A (pAC3162), or rrp40-W195R-Myc (pAC3259) were grown in 2 ml Leu− minimal medium overnight at 30°, 10 ml cultures with an OD600 = 0.4 were prepared and grown at 37° for 5 hr. Cells were collected by centrifugation (2163 × g), transferred to 2 ml screw cap tubes and stored at −80°. Following total RNA isolation from each cell pellet, 1 µg RNA was reverse transcribed to first strand cDNA using the M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR was performed on technical triplicates of cDNA (10 ng) from three independent biological replicates using NEL025c, U4, ITS-2 primers and control ALG10 primers (0.5 µM; Table S2), and QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR master mix (Qiagen) on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems; Tanneal: 55°; 44 cycles). The mean RNA levels were calculated by the ∆∆Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001), normalized to mean RNA levels in RRP40 cells, and converted and graphed as RNA fold change relative to RRP40, with error bars that represent the SD from the mean.

Immunoblotting

For analysis of C-terminally Myc-tagged Rrp40 and rrp40 protein expression levels, rrp40∆ cells (yAV1107) or RRP40-TAP cells expressing Rrp40-Myc (pAC3161), rrp40-G8A-Myc (pAC3162), rrp40-S87A (pAC3257), rrp40-W195R-Myc (pAC3259), rrp40-W195A-Myc (pAC3163), or rrp40-W195F-Myc (pAC3286) protein, or containing vector (pRS315) were grown in 2 ml Leu− minimal medium overnight at 30° to saturation, and 10 ml cultures with an OD600 = 0.4 were prepared and grown at 30 and 37° for 5 hr. Cell pellets were collected by centrifugation, transferred to 2 ml screw-cap tubes and stored at −80°. For analysis of EXOSC3 expression levels, mouse N2a cells (Klebe and Ruddle 1969) were transiently transfected with bicistronic CMV-IRES-EGFP vector (pIGneo) containing Myc-Exosc3 (pAC3417), Myc-Exosc3G31A (pAC3418), or Myc-Exosc3W237R (pAC3420) plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and cells were collected 24 hr after transfection.

Yeast cell lysates were prepared by resuspension of cells in 0.3 ml RIPA-2 Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 1% NP40; 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitors [1 mM PMSF; 3 ng/ml PLAC (pepstatin A, leupeptin, aprotinin, and chymostatin)], addition of 300 µl glass beads, disruption in a Mini Bead Beater 16 Cell Disrupter (Biospec) for 4 × 1 min at 25°, and centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°. Mouse N2a cell lysates were prepared by lysis in RIPA-2 Buffer, and centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°. Protein lysate concentration was determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Life Technologies). Whole cell lysate protein samples (20–50 µg) were resolved on Criterion 4–20% gradient denaturing gels (Bio-Rad), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) and Myc-tagged Rrp40 and EXOSC3 proteins were detected with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody 9B11 (1:2000; Cell Signaling), TAP-tagged Rrp40 protein was detected with peroxidase anti-peroxidase (PAP) antibody (1:5000; Sigma). As loading controls, 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (Pgk1) protein was detected with anti-Pgk1 monoclonal antibody (1:30,000; Invitrogen), and eIF5A protein was detected with a rabbit anti-eIF5A polyclonal antibody (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For transfection control, GFP from pIGneo bicistronic EGFP-Myc-Exosc3 vectors was detected with anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Protein stability assay

To determine the stability of wild-type Rrp40-Myc and rrp40-Myc variant in rrp40∆ (yAV1107), wild-type (MHY501) or doa3-1 (MHY3646) cells expressing Rrp40-Myc (pAC3161), rrp40-G8A (pAC3162), or rrp40-W195R (pAC3259), were grown in 10 ml Leu− minimal medium overnight at 30°, and 200 ml cultures with an OD600 = 0.4 were prepared. rrp40∆ (yAV1107) and RRP40-TAP cultures were grown for 2 hr at 30 or 37° and wild-type (MHY501) and doa3-1 (MHY3646) cultures were grown at 37° for 2 hr. Cycloheximide (CHX, Sigma) was added to the cultures at a final concentration of 100 µg/ml. Samples (20 ml) were taken immediately after CHX addition at 0 time point. rrp40∆ and RRP40-TAP cultures were grown at 30° or 37°, and wild-type and doa3-1 cultures were grown at 37° and 20 ml samples were collected at 5–35 min time points every 5 min, or 0.5–4.5 hr every 30 min. Cell sample pellets were collected by centrifugation, transferred to 2 ml screw cap tubes and stored at –80°. Protein lysates from cell sample pellets were prepared by resuspension of cells in 0.3 ml RIPA-2 Buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (as above), addition of 300 µl glass beads, disruption in a Mini Bead Beater 16 Cell Disrupter (Biospec) for 4 × 1 min at 25°, and centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°. Protein lysate concentration was determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Life Technologies). Protein lysate (30 µg) from each time point was analyzed by denaturing SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody to detect Myc-tagged Rrp40 and rrp40 proteins, and anti-Pgk1 monoclonal antibody to detect Pgk1 as a loading control.

Quantitation of immunoblots

The band intensities/areas from all immunoblots were quantitated using ImageJ v1.4 software (National Institutes of Health, MD; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), and relevant percentages of protein were calculated in Microsoft Excel for Mac 2011 (Microsoft Corporation). To quantitate the percentage of rrp40-Myc variant relative to wild-type Rrp40-Myc protein in rrp40∆ cell and RRP40-TAP cells, rrp40-Myc intensity was normalized to Pgk1 intensity and Rrp40-Myc intensity. To quantitate and graph the relative intensity of Rrp40-TAP protein and wild-type Rrp40-Myc protein, or rrp40-Myc variant, in RRP40-TAP cells, the Rrp40-TAP and R/rrp40-Myc intensity was normalized to Pgk1 intensity, and the relative intensities of Rrp40-TAP and R/rrp40-Myc were graphed as two stack columns using Microsoft Excel. To quantitate the percentage of Myc-EXOSC3 variant relative to wild-type Myc-EXOSC3 protein, Myc-EXOSC3 variant intensity was normalized to GFP intensity and Myc-EXOSC3 intensity. In the Rrp40 protein stability assays, to quantitate the percentage remaining of wild-type Rrp40-Myc protein or rrp40-Myc variant in rrp40∆, RRP40-TAP, wild-type, or doa3-1 cells at each time point relevant to time 0, Rrp40-Myc or rrp40-Myc protein intensity at each time point was normalized to Pgk1 intensity and Rrp40-Myc, or rrp40-Myc, protein intensity at time 0. For the exponential decay curves, these Rrp40 protein percentages were plotted and best fit/least-squares exponential curves were calculated using Microsoft Excel. For the inset graphs, the natural logarithm (ln) of Rrp40 protein percentages at each time point were plotted and fitted with least-squares lines using Microsoft Excel. All best fit lines had reasonable correlation coefficients (R2 = 0.89–0.99). The slopes of the best fit lines were calculated to determine the decay rate constants (k) for the Rrp40 proteins, and the half-lives (t1/2) of the Rrp40 proteins were calculated using the equation t1/2 = ln(2)/k as previously used to determine protein half-lives (Belle et al. 2006). The quantitation is for specific experiments shown in figures, but is representative of multiple experiments.

Blue native-PAGE

Blue native-PAGE (BN-PAGE) was performed essentially as described in a published protocol (Wittig et al. 2006). For analysis of wild-type Rrp40-Myc and rrp40-Myc variants expressed in S. cerevisiae cells by BN-PAGE, wild-type (MHY501), doa3-1 (MHY3646), or rrp40∆ cells (yAV1107) cells expressing Rrp40-Myc (pAC3161), rrp40-G8A-Myc (pAC3162), rrp40-S87A (pAC3257), or rrp40-W195R-Myc (pAC3259) protein were grown in 2 ml Leu− minimal medium overnight at 30° to saturation, and 10 ml cultures with an OD600 = 0.4 were prepared; wild-type and doa3-1 cells were grown at 37°, and rrp40∆ cells at 30° for 5 hr. Cell pellets were collected by centrifugation, transferred to 2 ml screw-cap tubes and stored at −80°. Yeast cell lysates were prepared by resuspension of cells in 0.3 ml IPP150 Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; 150 mM NaCl; 0.1% NP40) supplemented with protease inhibitors [1 mM PMSF; 3 ng/ml PLAC (pepstatin A, leupeptin, aprotinin, and chymostatin)], addition of 300 µl glass beads, disruption in a Mini Bead Beater 16 Cell Disrupter (Biospec) for 4 × 1 min at 25°, and centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°. Whole cell lysate protein samples (20–50 µg) were mixed with nondenaturing loading dye and resolved on Criterion 4–20% gradient BN-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad). The upper chamber of the electrophoresis apparatus contained Cathode buffer B (50 mM Tricine; 7.5 mM Imidazole; 0.2% Coomassie blue G-250; pH 7), and the lower chamber contained Anode buffer (25 mM Imidazole, pH 7), and the BN-PAGE gel was resolved at 100 V for 2–3 hr at 4°. The proteins were transferred to PDVF membranes (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer (50 mM Tricine; 7.5 mM Imidazole; pH 7) at 20 V for 3 hr at 4°. Myc-tagged Rrp40 and rrp40 proteins were detected with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody, and the Pgk1 protein was detected with anti-Pgk1 monoclonal antibody as a loading control.

Glycerol gradient fractionation

For analysis of wild-type Rrp40-Myc and rrp40-W195R-Myc variants expressed in S. cerevisiae cells by glycerol gradient fractionation, doa3-1 (MHY3646) cells expressing Rrp40-Myc (pAC3161) or rrp40-W195R-Myc (pAC3259) protein were grown in 10 ml Leu− minimal medium overnight at 30° to saturation, and 200 ml doa3-1 cultures with an OD600 = 0.4 were prepared and grown at 37° for 5 hr. Cell pellets were collected by centrifugation, transferred to 2 ml screw-cap tubes, and stored at −80°. Yeast cell lysates were prepared by resuspension of cells in 0.5 ml native lysis buffer [10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5; 2 mM MgCl2; 10 mM KCl; 0.5% NP-40; 0.5 mM EDTA; 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM DTT; Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Invitrogen)], addition of 300 µl glass beads, disruption in a Mini Bead Beater 16 Cell Disrupter (Biospec) for 4 × 1 min at 25°, and centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°. Cell lysate (2 mg) was layered on top of a 10–30% glycerol gradient buffer [10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5; 2 mM MgCl2; 10 mM KCl; 0.5 mM EDTA; 150 mM NaCl] in 14 × 89 mm tubes (Beckman Coulter) and centrifuged in a SW 41 Ti swinging-bucket rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 134,000 × g for 12 hr at 4°. Gradients were fractionated as 500 µl fractions from top to bottom. Every other fraction (40 µl) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody to detect Myc-tagged Rrp40 and rrp40-W195R, and anti-Pgk1 monoclonal antibody to detect Pgk1 as a loading control.

Data availability

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article. All strains and plasmids employed are available upon request.

Results

PCH1b patients have mutations that alter conserved EXOSC3 residues

PCH1b is caused by mutations in the EXOSC3 exosome cap subunit gene (Wan et al. 2012), but, thus far, only a few specific amino acid substitutions have been definitively linked to PCH1b (Figure 1, B and C). Specifically, PCH1b patients homozygous for EXOSC3 (G31A) have a severe disease, while patients homozygous for EXOSC3 (D132A) have a less severe disease (Figure 1C) (Wan et al. 2012; Biancheri et al. 2013; Rudnik-Schoneborn et al. 2013; Schwabova et al. 2013; Eggens et al. 2014). EXOSC3 (D132A) has also been found in compound heterozygosity with likely null alleles in PCH1b patients with severe disease (Wan et al. 2012; Rudnik-Schoneborn et al. 2013; Eggens et al. 2014). On the other hand, EXOSC3 (G31A) has not been found in combination with obvious null alleles, but it has been found in compound heterozygosity with EXOSC3 (W238R) (Wan et al. 2012; Rudnik-Schoneborn et al. 2013). Although loss of EXOSC3 has been modeled in zebrafish by knockdown with antisense morpholinos (Wan et al. 2012), the functional consequences of specific amino acid substitutions in EXOSC3 have not previously been analyzed in detail.

To begin to analyze specific PCH1b-associated amino acid substitutions in EXOSC3, we generated a protein sequence alignment of human EXOSC3, the budding yeast EXOSC3 ortholog, Rrp40, and other eukaryotic EXOSC3/Rrp40 orthologs (Figure S1). The human RNA exosome subunit EXOSC2 is similar to EXOSC3, so we also included human EXOSC2 and its budding yeast ortholog, Rrp4, in the alignment. As EXOSC2 and EXOSC3 are replaced by Rrp4 in Archaea (Buttner et al. 2005; Lorentzen et al. 2007), we also aligned archaeal Rrp4. Human EXOSC3 residues substituted in PCH1b are among the most conserved residues in this protein (Figure S1). Only 10 human EXOSC3 residues are perfectly conserved in the sequences analyzed, and two of these conserved residues are the PCH1b-associated EXOSC3 residues, G31 and W238 (Figure S1 and Figure 1B). EXOSC3 residue D132 is also conserved in most EXOSC3/Rrp40 orthologs, but it is replaced by serine in budding yeast Rrp40 and most other ascomycete fungi Rrp40 orthologs (Figure S1 and Figure 1B). The EXOSC3/Rrp40 protein contains three domains: an N-terminal domain, an S1 putative RNA binding domain, and a KH putative RNA binding domain (Figure 1B). Notably, the human EXOSC3-G31/budding yeast Rrp40-G8 residue is located in the N-terminal domain, EXOSC3-D132/Rrp40-S87 residue is located in the S1 domain, and EXOSC3-W238/Rrp40-W195 residue is located in the KH domain (Figure 1B).

To assess the potential interactions of PCH1b-associated EXOSC3/Rrp40 residues, we examined both human and budding yeast RNA exosome structures (Liu et al. 2006; Makino et al. 2013; Wasmuth et al. 2014) (Figure 1D). Based on these structures, the positions of the PCH1b-associated conserved residues (black, bold) in EXOSC3/Rrp40 (blue) are shown within the context of the RNA exosome (Figure 1D). Strikingly, although PCH1b-associated EXOSC3/Rrp40 residues are not clustered together in primary sequence, and are located in different EXOSC3/Rrp40 domains (Figure 1B) (Wan et al. 2012), the residues are all in positions that could be important for interactions with other RNA exosome subunits. Specifically, Rrp40 residue G8 is packed against Rrp46 residues S129, M130, and V168 (Figure 1D). Substituting any bulkier side chain at Rrp40 G8, including substitution to alanine corresponding to the PCH1b-associated G31A substitution, could interfere with Rrp40-Rrp46 interaction. Rrp40 residue S87 forms a hydrogen bond with Rrp40 Q89 (Figure 1D), which could be disrupted by S87A substitution in Rrp40 corresponding to the PCH1b-associated D132A substitution in EXOSC3. In the human exosome structure, the corresponding EXOSC3 residue D132 appears to form a hydrogen bond with EXOSC3 G134 (Figure 1D). Disrupting this hydrogen bond could impair the folding of a loop within the Rrp40/EXOSC3 S1 domain. Unlike Rrp40 residues G8 and S87, Rrp40 W195 is not located at an exosome subunit interface, but could still be important intersubunit interactions. Rrp40 W195 is located in a pocket surrounded by a loop containing Rrp40 D152, which is positioned to make a salt bridge to Rrp45 K13. In the human exosome structure, although not identically positioned, the corresponding EXOSC3 residue W238 is located in a pocket near EXOSC3 D196 and EXOSC9 R12. The Rrp40 W195R substitution could therefore alter the position of D152, which could weaken interaction with Rrp45. In addition to interactions with other exosome subunits, the PCH1b-associated EXOSC3/Rrp40 residues could also lie in close proximity to RNA or could contribute to interactions with RNA exosome cofactors.

We used the budding yeast S. cerevisiae to begin to assess the functional consequences of the PCH1b-associated EXOSC3-G31A, -D132A, and -W238R substitutions because these residues are highly conserved in EXOSC3/Rrp40 orthologs, and located in key structural EXOSC3/Rrp40 domains. Furthermore, the budding yeast RNA exosome has been extensively characterized, and is similar to the human RNA exosome (Sloan et al. 2012). As illustrated in Figure 1B, we created mutations in the budding yeast RRP40 gene that result in the following rrp40 amino acid substitution variants: rrp40-G8A (corresponding to EXOSC3-G31A); rrp40-S87A (corresponding to D132A); and rrp40-W195R (corresponding to W238R). These rrp40 variants were used to assess the functional consequences of these substitutions in the Rrp40 exosome subunit.

Amino acid substitutions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rrp40 corresponding to PCH1b-associated EXOSC3 substitutions impair function

In budding yeast, all of the core RNA exosome subunits are encoded by essential genes (Allmang et al. 1999). As a first test of the functional consequences of PCH1b-associated substitutions, we assessed whether the rrp40 mutant genes could complement the lethality of a yeast rrp40Δ mutant. For these studies, we examined the rrp40-G8A, rrp40-S87A, and rrp40-W195R variants (Figure 2). As the change of tryptophan 195 to arginine in rrp40-W195R is a dramatic change, we also changed tryptophan 195 to alanine (rrp40-W195A) to remove the large hydrophobic residue without simultaneously introducing a positive charge. In addition, we created a very conservative change of tryptophan 195 to phenylalanine (rrp40-W195F), which retains the large hydrophobic residue.

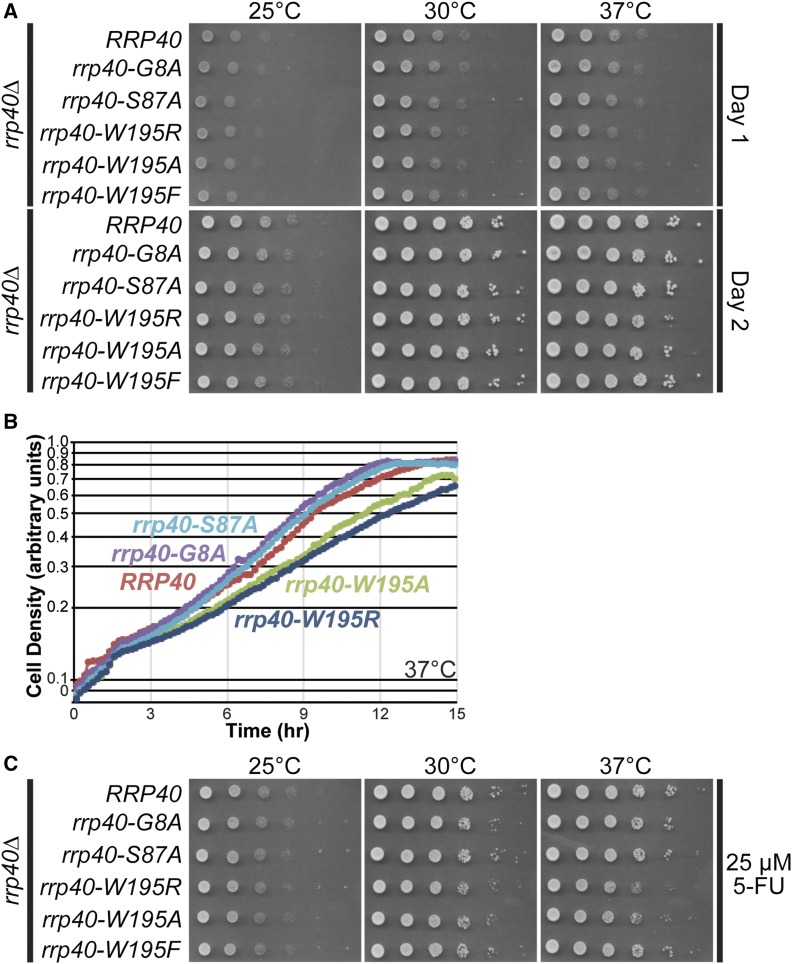

Figure 2.

S. cerevisiae cells that express rrp40-W195R or rrp40-W195A as the sole copy of Rrp40 show impaired growth at 37°. Growth of rrp40∆ cells containing only wild-type RRP40 or mutant rrp40 (G8A, S87A, W195R, W195A, or W195F) plasmid was analyzed by: (A) Serial dilution, spotting on minimal medium plates, and growth at indicated temperatures for 1 day (Day 1) or 2 days (Day 2). (B) Growth in liquid culture at 37° and optical density measurements over time. (C) Serial dilution, spotting on minimal medium plates containing 5-FU, and growth at indicated temperatures.

We grew rrp40∆ cells expressing each rrp40 substitution variant as the sole copy of the essential Rrp40, serially diluted and spotted the cells on plates, and incubated the plates at various temperatures (Figure 2A). In this solid medium end-point assay, rrp40-W195R and rrp40-W195A mutant cells gave rise to smaller colonies at 37°, indicative of a modest growth defect that is most noticeable on day 1 of growth. To provide a more quantitative comparison of growth rates, we also performed growth assays in liquid cultures at 37° (Figure 2B and Figure S2). This analysis revealed that rrp40-W195R and rrp40-W195A mutant cells grow at a slower rate than wild-type RRP40 cells, with doubling times increased by 13 and 20%, respectively, compared to RRP40 cells (Figure 2B and Figure S2A). The other rrp40 mutants analyzed, rrp40-G8A and rrp40-S87A, grew in a manner indistinguishable from wild-type RRP40 cells (Figure 2B). The rrp40-W195F mutant also grew similarly to wild-type RRP40 cells (Figure S2B). At 30°, the rrp40-W195R and rrp40-W195A mutant cells also reproducibly grew more slowly than the other mutants, although the difference was less pronounced than at 37°. In a plasmid shuffle assay, in which rrp40∆ cells containing an RRP40URA3 maintenance plasmid and each rrp40 mutant were grown on 5-FOA plates at several temperatures to select against the maintenance plasmid, the rrp40-W195R and rrp40-W195A mutant cells also showed slow growth at 30 and 37°, whereas rrp40-W195F cells showed no growth defect (Figure S3).

We took advantage of the fact that the exosome mutants, such as rrp6∆, are sensitive to the antimetabolite 5-FU, an inhibitor of thymidine synthesis that impairs both DNA and RNA metabolism (Fang et al. 2004; Lum et al. 2004). To further assess the function of rrp40-W195R and rrp40-W195A, we serially diluted and spotted rrp40 mutants on solid medium plates containing 5-FU, and incubated the plates at several temperatures (Figure 2C). The rrp40-W195R and rrp40-W195A mutant cells show reduced growth on 5-FU plates at 37° relative to wild-type RRP40 cells. In contrast, the rrp40-W195F mutant cells show growth similar to RRP40 cells. These results demonstrate that no single amino acid substitution in Rrp40, corresponding to a PCH1b-associated substitution in EXOSC3, causes a complete loss of Rrp40 function, and that substitutions that remove the large hydrophobic W195 residue modestly impair cell growth. These results are not surprising as Rrp40 is essential in budding yeast (http://www.yeastgenome.org), and loss of EXOSC3 is embryonic lethal in mice (http://www.mousephenotype.org); thus, some threshold level of function is likely required in EXOSC3 for viability and development in humans.

The rrp40-W195R mutant exhibits elevated levels of exosome RNA targets

To assess whether the slow growth observed for the rrp40-W195R mutant correlates with a change in RNA exosome function, we examined the steady-state level of several well defined RNA exosome target transcripts, the NEL025C cryptic unstable transcript (CUT), U4 snRNA, and ITS2 rRNA (Wasmuth and Lima 2012). Levels of NEL025C and U4 RNA were modestly, but statistically significantly, increased in rrp40-W195R mutant cells at 37° (Figure 3, A and B), consistent with the change in cell growth. The level of ITS2 RNA was not changed significantly, suggesting that not all targets are affected equally (Figure 3C). No significant difference in the level of the RNA targets was detected in the rrp40-G8A mutant cells. These results provide further evidence that RNA exosome function is compromised in the rrp40-W195R mutant cells.

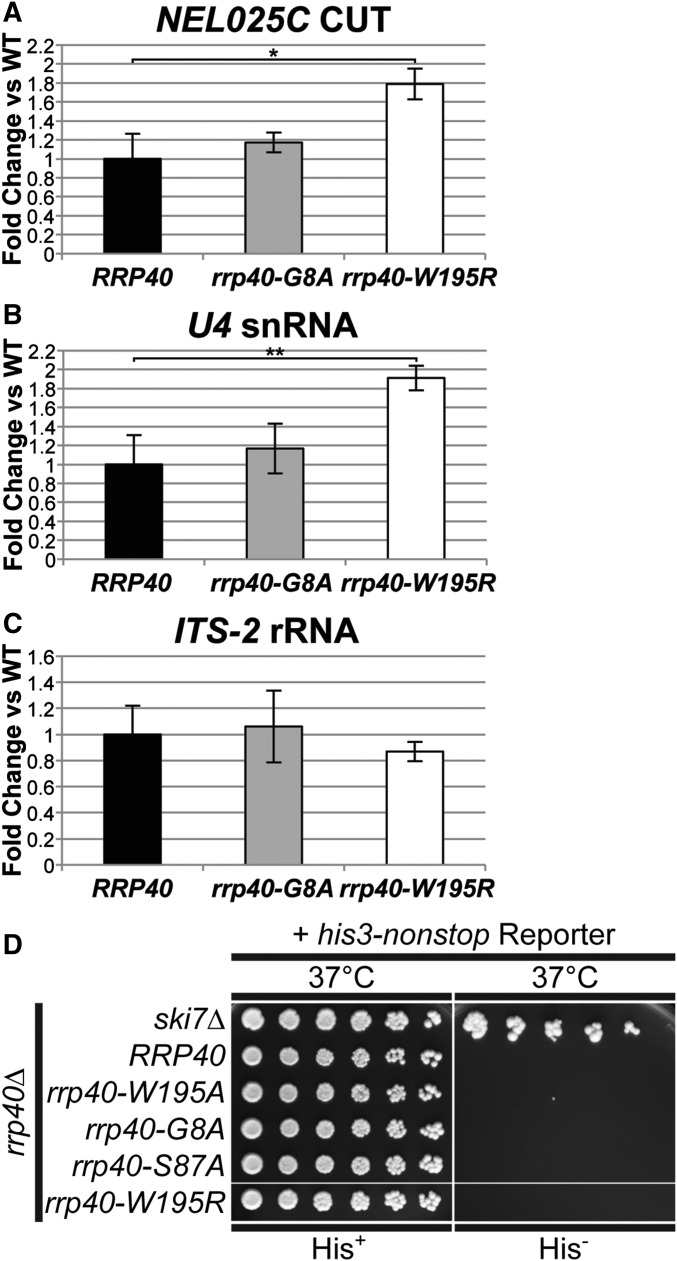

Figure 3.

The rrp40-W195R mutant cells show elevated levels of exosome target transcripts but do not exhibit impaired cytoplasmic exosome function. (A–C) The rrp40-W195R mutant cells show a statistically significant increase in the levels of noncoding RNAs, (A) NEL025c CUT and (B) U4 snRNA, but not (C) ITS-2 rRNA, at 37°. Total RNA from rrp40∆ cells containing only wild-type RRP40 or mutant rrp40 (G8A; W195R) grown at 37° was measured by quantitative RT-PCR using NEL025c CUT, U4 snRNA, and ITS-2 rRNA primers as described in Material and Methods. Relative RNA levels were measured in triplicate biological samples, normalized to a control ALG10 transcript by the ∆∆Ct method, averaged, and shown graphically as fold increase relative to wild-type RRP40. Error bars denote SD. The difference in NEL025c CUT levels between rrp40-W195R and wild-type cells is significant (P = 0.0114; denoted by *) and the difference in U4 snRNA levels between rrp40-W195R and wild-type cells is very significant (P = 0.0090; denoted by **). The differences in RNA levels between rrp40-G8A and wild-type cells are not significant. Statistically significant differences in mean RNA levels were determined using the unpaired t-test. (D) The rrp40 mutant cells do not rescue a his3-nonstop mRNA reporter, which is degraded rapidly by the cytoplasmic RNA exosome (van Hoof et al. 2002), to restore growth on medium lacking histidine, suggesting that rrp40 mutants do not impact cytoplasmic RNA exosome function. As a control, deletion of SKI7, encoding a key cytoplasmic RNA exosome cofactor (van Hoof et al. 2000), rescues the his-nonstop reporter and thus confers growth on medium lacking histidine. The rrp40∆ cells containing wild-type RRP40 or mutant rrp40 (G8A; S87A; W195R; W195A) plasmid and the his3-nonstop mRNA reporter plasmid, and ski7∆ cells containing the his3-nonstop mRNA reporter plasmid were serially diluted and spotted onto minimal medium plates lacking histidine (His−) or control plates containing histidine (His+) and grown at 37°.

We next extended our analyses to assess whether these rrp40 variants affect the cytoplasmic functions of the RNA exosome. The rationale for examining cytoplasmic RNA exosome function is threefold: first, the cytoplasmic functions of the RNA exosome are nonessential, and thus distinct from those tested above (Jacobs Anderson and Parker 1998; Schaeffer et al. 2010); second, residue substitutions in a different RNA exosome cap protein (Csl4/EXOSC1) inactivate cytoplasmic RNA exosome function without blocking the essential (nuclear) function (van Hoof et al. 2000); and third, the hypothesis has been put forth that PCH1b and PCH1c are the result of a defect in cytoplasmic mRNA degradation by the RNA exosome (Boczonadi et al. 2014).

To examine cytoplasmic exosome function in rrp40 mutants, we employed a his3-nonstop reporter assay that exploits the observation that the budding yeast cytoplasmic RNA exosome is required for the degradation of mRNAs that lack stop codons (van Hoof et al. 2002). In cells with functional cytoplasmic exosome, the his3-nonstop mRNA reporter, which encodes the His3 protein and lacks stop codons, is degraded, no histidine is made, and the cells cannot grow on media lacking histidine. In cells with defective cytoplasmic RNA exosome, the his3-nonstop mRNA reporter is stabilized, biosynthesis of histidine proceeds, and cells can grow on media lacking histidine. The rrp40∆ cells expressing each rrp40 variant as the sole copy of Rrp40, and containing the his3-nonstop reporter, were serially diluted and spotted onto solid medium lacking histidine (His−) and control medium containing histidine (His+) (Figure 3D). As a control for impaired cytoplasmic exosome function, we also diluted and spotted a ski7Δ strain containing the his3-nonstop reporter, as Ski7 is a cofactor required for cytoplasmic exosome function (van Hoof et al. 2002). As expected, the ski7∆ control strain grew on His− medium (Figure 3D). In contrast, none of the experimental rrp40 mutants grew on His− medium, indicating that cytoplasmic exosome-mediated nonstop mRNA decay proceeds normally in cells expressing these rrp40 variants (Figure 3D). These results suggest that amino acid substitutions linked to PCH1b do not block the function of the cytoplasmic RNA exosome, at least in the budding yeast system.

The rrp40-W195R variant is expressed at low level and is unstable when expressed as the sole copy of Rrp40

To test whether amino acid substitutions in Rrp40 corresponding to those in PCH1b-associated EXOSC3 impact protein levels, we analyzed the steady-state expression of Myc-tagged wild-type Rrp40, rrp40-W195R, and the other rrp40 variants as the sole copy of Rrp40 in rrp40∆ cells grown at 30 and 37° by immunoblotting (Figure 4A). The steady-state level of the rrp40-W195R variant was reduced about threefold, whereas the levels of rrp40-S87A and rrp40-G8A variants were within twofold of wild-type Rrp40 at 37° (Figure 4A). The level of the rrp40-W195A variant, which also caused slow growth, was also reduced (57% of wild-type level) at 37° (Figure 4A). In contrast, the conservative rrp40-W195F variant level was modestly reduced (71% of wild-type level) (Figure 4A). These data indicate that the W195R substitution in Rrp40, corresponding to W238R in EXOSC3, strongly reduces the level of the protein at 37° and suggest the rrp40-W195R variant may be less stable than wild-type Rrp40.

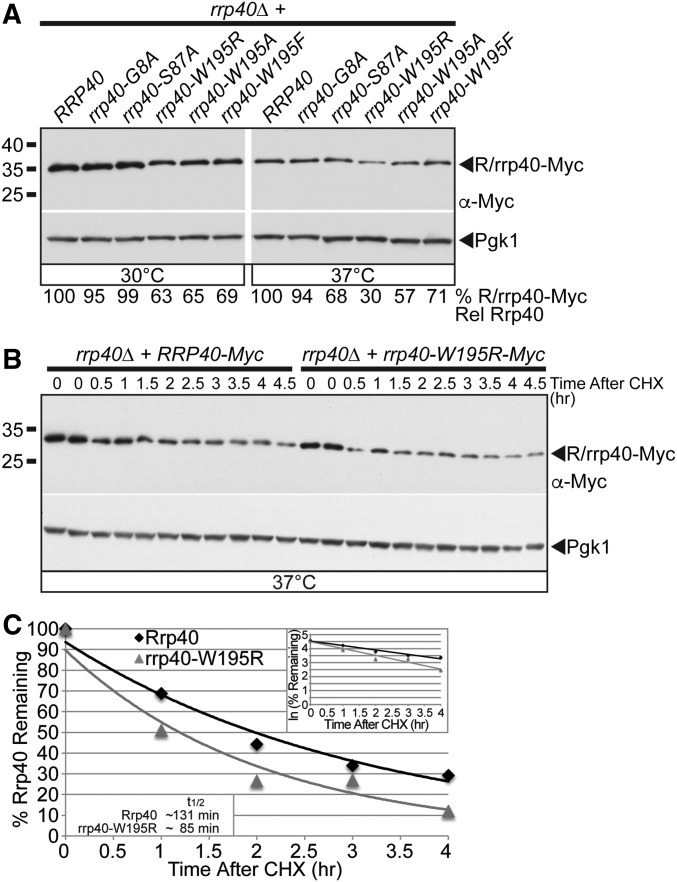

Figure 4.

The rrp40-W195R variant is less stable than wild-type Rrp40 in cells as the only copy of Rrp40. (A) The steady-state level of the rrp40-W195R and rrp40-W195A variant is decreased compared to wild-type Rrp40 in rrp40∆ cells at 37°. Lysates of rrp40∆ cells expressing Myc-tagged wild-type Rrp40 or rrp40 variant (G8A, S87A, W195A, W195R, and W195F) grown at 30 or 37° were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody to detect Myc-tagged Rrp40 and rrp40 variants (R/rrp40-Myc), and anti-Pgk1 antibody to detect Pgk1 as a loading control. The percentage of Rrp40-Myc or rrp40-Myc variant relative to wild-type Rrp40-Myc (% R/rrp40-Myc Rel Rrp40) is shown below each lane, and was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. (B) The rrp40-W195R variant is unstable in rrp40∆ cells at 37°. The rrp40∆ cells expressing Myc-tagged Rrp40 or rrp40-W195R were treated with the translation inhibitor CHX. Samples were collected over time (0–4.5 hr) and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody to detect Myc-tagged Rrp40 and rrp40-W195R protein (R/rrp40-Myc), and anti-Pgk1 antibody to detect Pgk1 as a loading control. (C) The immunoblot shown in (B) was quantitated to plot the percentage of Rrp40 and rrp40-W195R protein remaining at each time point relative to inhibition of translation at time 0 in rrp40∆ cells. The inset graph shows the natural logarithm (ln)-transformed percentages of Rrp40 and rrp40-W195R at time points 0–4 hr fitted with linear least-squares fit lines to determine the decay rate constant (k) for each protein. The inset half-lives (t1/2) of Rrp40 and rrp40-W195R in rrp40∆ cells at 37° were calculated from each decay rate constant using the equation t1/2 = ln(2)/k (Belle et al. 2006). Further details on the measurement of the percentages of protein using protein band intensities and calculation of the protein half-lives are described in Materials and Methods. Quantitation is for the specific experiment shown, but is representative of multiple experiments.

To examine the stability of the rrp40-W195R variant, we analyzed the levels of the Myc-tagged rrp40-W195R and wild-type Rrp40 proteins expressed in rrp40∆ cells over time at 37° after cycloheximide treatment (Figure 4B). The exponential decay curves from these data reveal that the rrp40-W195R variant is unstable with a shorter half-life (t1/2 ∼85 min) compared to wild-type Rrp40 (t1/2 ∼131 min) at 37° (Figure 4C). We also examined the stability of the rrp40-W195R and rrp40-G8A variants at 30° (Figure S4), and found that rrp40-W195R is unstable (t1/2 ∼116 min), but the rrp40-G8A variant is stable (t1/2 ∼255 min), relative to wild-type Rrp40 (t1/2 ∼222 min) at 30°. These results indicate that the rrp40-W195R variant is unstable relative to wild-type Rrp40.

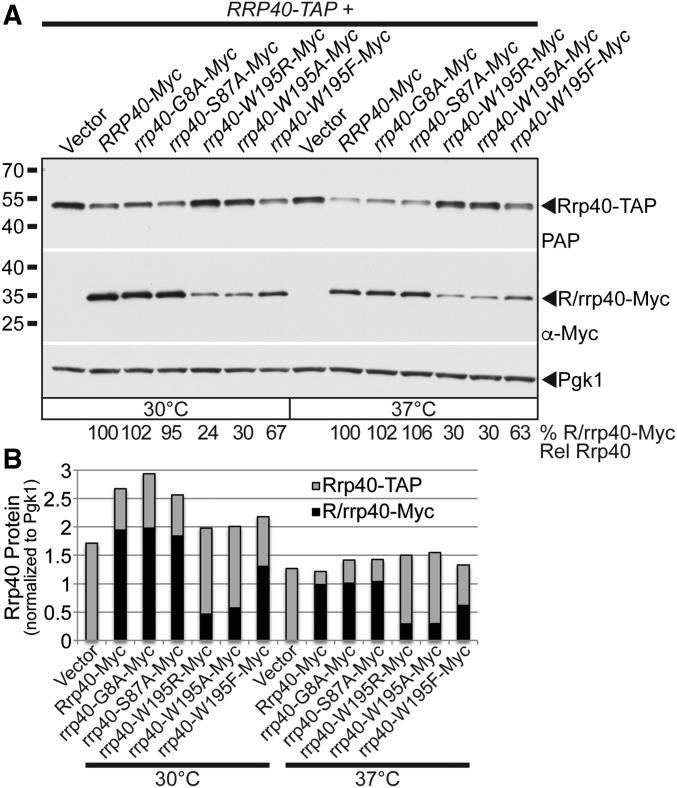

The rrp40-W195R variant is expressed at greatly reduced level when coexpressed with wild-type Rrp40 in an in vivo competition assay

A potential explanation for the reduced stability of the rrp40-W195R variant in rrp40∆ cells could be that the rrp40-W195R variant does not assemble efficiently into the exosome complex, and is therefore targeted for degradation by the proteasome. If this impaired exosome assembly model is correct, one prediction would be that the rrp40-W195R variant would be out-competed by wild-type Rrp40 for assembly into the exosome in an in vivo competition setting. We examined the expression of Myc-tagged wild-type Rrp40, and rrp40 variants, in RRP40-TAP cells that coexpress a tandem affinity purification (TAP)-tagged copy of wild-type Rrp40 at 30 and 37° by immunoblotting (Figure 5A). The steady-state levels of the rrp40-W195R and rrp40-W195A variants were decreased (to 24–30% of the wild-type level) in the RRP40-TAP cells at both 30 and 37° (Figure 5A). However, the level of the conservative rrp40-W195F variant was much less affected (Figure 5A), suggesting that a large hydrophobic residue is required at position 195 in Rrp40. In contrast, the levels of rrp40-G8A and rrp40-S87A variants were similar to wild-type Rrp40 level (95–106%) (Figure 5A). Quantitation of the levels of Rrp40-Myc, rrp40-Myc variants, and Rrp40-TAP in the immunoblot show that, in RRP40-TAP cells with low levels of rrp40-W195R or rrp40-W195A variants, there was a high level of Rrp40-TAP, whereas in cells with high levels of rrp40-G8A-Myc or rrp40-S87A-Myc variant, there was a low level of Rrp40-TAP (Figure 5B). These data show that the level the rrp40-W195R variant is quite reduced in RRP40-TAP cells coexpressing wild-type Rrp40, and that the level of rrp40-W195R is much lower in RRP40-TAP cells (24% of wild-type level; Figure 5A) than it is in rrp40∆ cells (63% of wild-type level; Figure 4A) at 30°. These results suggest that the rrp40-W195R variant is more unstable in the presence wild-type Rrp40, and that rrp40-W195R cannot compete efficiently with wild-type Rrp40 for assembly into the exosome.

Figure 5.

In an in vivo competition experiment, the rrp40-W195R-Myc variant is present at a greatly reduced level relative to wild-type Rrp40-Myc in cells coexpressing wild-type Rrp40-TAP. (A) rrp40-W195R-Myc and rrp40-W195A variants are expressed at lower steady-state levels compared to Rrp40-Myc in RRP40-TAP cells at 30 and 37°. Lysates of RRP40-TAP cells expressing wild-type Rrp40-Myc, or variant rrp40-Myc (G8A, S87A, W195R, W195A, and W195F) grown at 30 or 37° were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody to detect Myc-tagged Rrp40 and rrp40 variants (R/rrp40-Myc), PAP antibody to detect Rrp40-TAP, and anti-Pgk1 antibody to detect Pgk1 as a loading control. The percentage of Rrp40-Myc and rrp40-Myc variant relative to wild-type Rrp40-Myc (% R/rrp40-Myc Rel Rrp40) is shown below each lane, and was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. (B) The immunoblot in (A) was quantitated to graph the relative intensity of wild-type Rrp40-Myc, variant rrp40-Myc, Rrp40-TAP protein bands in cells coexpressing R/rrp40-Myc and Rrp40-TAP at 30 and 37°. Cells with low levels of rrp40-W195R-Myc or rrp40-W195A-Myc variant have high levels of Rrp40-TAP. Cells with high levels of rrp40-G8A-Myc or rrp40-S87A variant have low levels of Rrp40-TAP. Further details on the measurement of the protein band intensities are described in Materials and Methods. Quantitation is for the specific experiment shown, but is representative of multiple independent experiments.

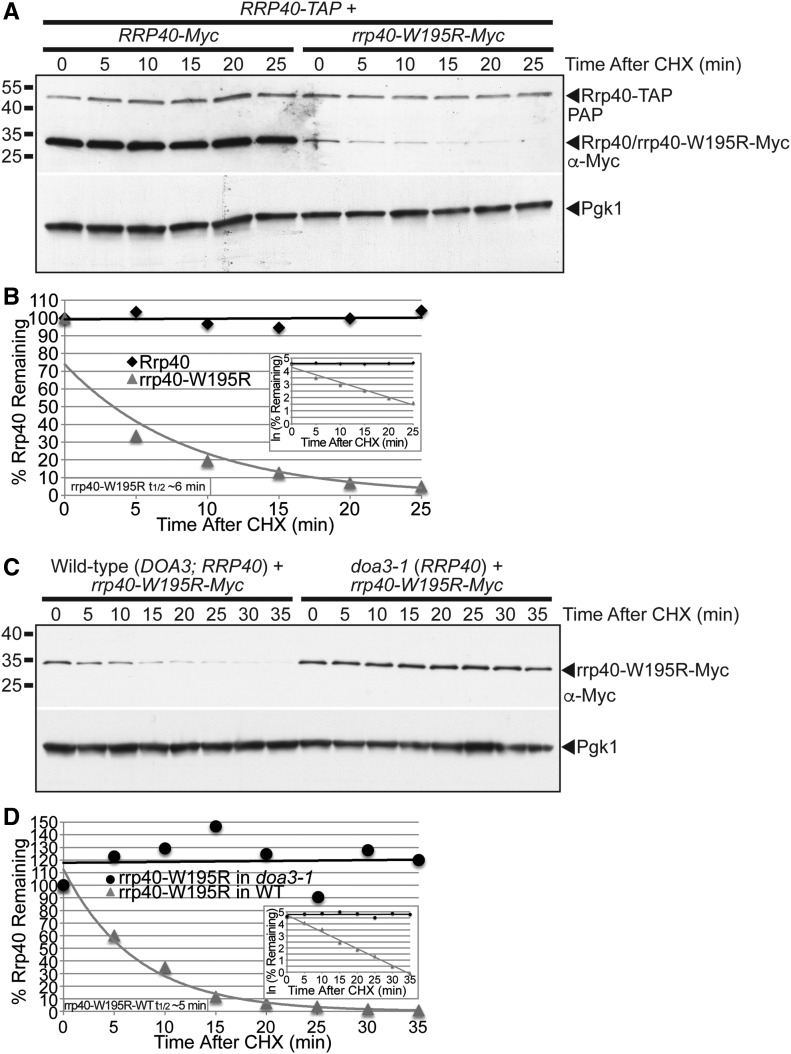

The rrp40-W195R variant is highly unstable, and rapidly degraded by the proteasome when coexpressed with wild-type Rrp40

To assess the stability of the rrp40-W195R variant in the presence of wild-type Rrp40, we examined the levels of Myc-tagged rrp40-W195R and Myc-tagged, wild-type Rrp40 in RRP40-TAP cells grown at 30° over time after cycloheximide treatment (Figure 6A). The exponential decay curves from these data reveal that the rrp40-W195R-Myc variant is highly unstable in RRP40-TAP cells with a very short half-life (t1/2 ∼6 min) compared to wild-type Rrp40-Myc at 30° (Figure 6B). In comparison, the half-life of rrp40-W195R-Myc in rrp40∆ cells at 30° was much longer (t1/2 ∼116 min), as described previously (Figure S4). This in vivo competition assay suggests that wild-type Rrp40 is assembled more efficiently in a stable RNA exosome complex than the rrp40-W195R variant.

Figure 6.

The rrp40-W195R variant is unstable and degraded by the proteasome in S. cerevisiae cells coexpressing wild-type Rrp40. (A) The level of rrp40-W195R-Myc variant decreases more rapidly than wild-type Rrp40-Myc over time in cells coexpressing wild-type Rrp40-TAP at 30°. RRP40-TAP cells expressing wild-type Rrp40-Myc or rrp40-W195R variant at 30° were treated with CHX to inhibit translation. Samples were collected over time (0–25 min) and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody to detect Myc-tagged proteins (Rrp40/rrp40-W195R-Myc), peroxidase anti-peroxidase (PAP) antibody to detect Rrp40-TAP, and anti-Pgk1 antibody to detect Pgk1 as a loading control. (B) The immunoblot shown in (A) was quantitated to plot the percentage of Rrp40-Myc and rrp40-W195R-Myc protein remaining at each time point relative to inhibition of translation at time 0 in RRP40-TAP cells. The inset graph shows the natural logarithm (ln)-transformed percentages of Rrp40 and rrp40-W195R at time points 0–25 min fitted with linear least-squares fit lines to determine the decay rate constant (k) for each protein. The inset half-life (t1/2) of rrp40-W195R in RRP40-TAP cells at 30° of ∼6 min was calculated from the decay rate constant using the equation t1/2 = ln(2)/k (Belle et al. 2006). (C) The level of rrp40-W195R-Myc variant is increased in doa3-1 proteasome mutant cells coexpressing wild-type Rrp40 at 37°. Wild-type or doa3-1 cells expressing rrp40-W195R-Myc protein at 37° were treated with CHX. Samples were collected over time (0–35 min) and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody to detect rrp40-W195R-Myc protein, and anti-Pgk1 antibody to detect Pgk1 as a loading control. (D) The immunoblot shown in (C) was quantitated to plot the percentage of rrp40-W195R-Myc protein at each time point in wild-type and doa3-1 mutant cells. The inset graph shows the natural logarithm (ln)-transformed percentages of rrp40-W195R at time points 0–35 min in wild-type or doa3-1 cells fitted with linear least-squares fit lines to determine the decay rate constant (k) for each protein. The inset half-life (t1/2) of rrp40-W195R in wild-type cells at 30° of ∼5 min was calculated as described in (B). Further details on the measurement of the protein band intensities and calculation of the protein half-lives are described in Materials and Methods. Quantitation is for the specific experiment shown, but is representative of multiple experiments.

We hypothesized that the rapid degradation of the rrp40-W195R variant in cells coexpressing wild-type Rrp40 is mediated by the proteasome. To directly test this hypothesis, we compared the stability of rrp40-W195R-Myc in wild-type cells with fully functional proteasome to doa3-1 mutant cells expressing a temperature-sensitive variant of the Doa3 proteasome subunit (Li et al. 2007). Both wild-type and doa3-1 cells also expressed endogenous, untagged, wild-type Rrp40. We examined the stability of rrp40-W195R in wild-type or doa3-1 cells at 37° over time after cycloheximide treatment (Figure 6C). The stability of rrp40-W195R is greatly increased in doa3-1 cells shifted to the nonpermissive temperature of 37°, where proteasome function is impaired compared to wild-type cells (Figure 6C). The exponential decay curves from these data reveal that rrp40-W195R is stable over the course of 35 min in doa3-1 proteasome mutant cells, but is very unstable with a short half-life (t1/2 ∼5 min) in wild-type cells (Figure 6D). These results indicate that the rrp40-W195R variant is degraded by the proteasome, and suggest that cells can selectively discriminate and target the rrp40-W195R variant for proteasome-mediated degradation when wild-type Rrp40 is available.

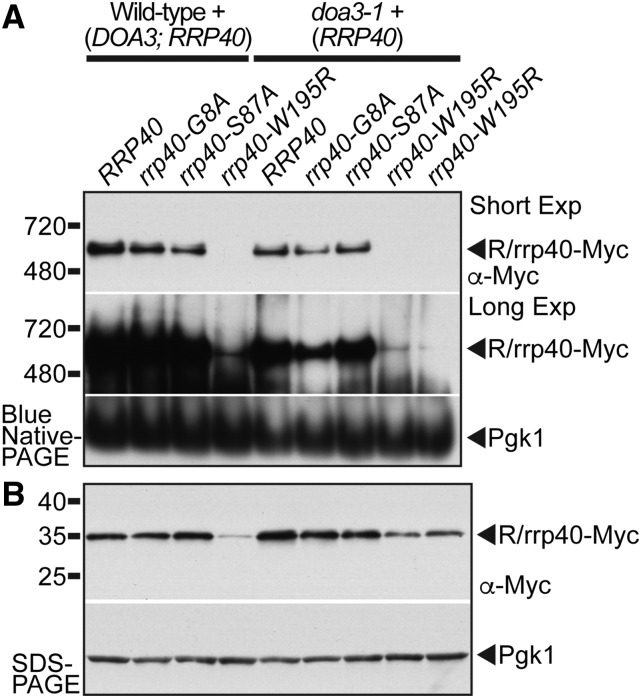

The rrp40-W195R variant associates less efficiently with the exosome complex when coexpressed with wild-type Rrp40

The reduced stability of the rrp40-W195R variant when coexpressed with wild-type Rrp40 could be explained by reduced assembly into the exosome complex. To examine the association of rrp40 variants with the exosome, we assessed the amount and size of Myc-tagged Rrp40 and rrp40 complexes in wild-type and doa3-1 cells grown at 37° by native-PAGE (Figure 7A). We used the doa3-1 proteasome mutant cells to increase the amount of rrp40-W195R for comparison to wild-type Rrp40. A high amount of wild-type Rrp40 in wild-type and doa3-1 cells migrates as a single complex of ∼600 kDa on a native gel (Figure 7A). This band size is consistent with the 600 kDa size reported for the 11-subunit yeast exosome complex (Liu et al. 2006). In contrast, a very low amount of the rrp40-W195R variant migrating as a 600 kDa complex is detected even upon long exposure of the immunoblot (Figure 7A). The amounts of the rrp40-G8A and rrp40-S87A variants migrating as a 600 kDa complex are similar to wild-type Rrp40 (Figure 7A). Importantly, analysis of the same lysates used in the native-PAGE by denaturing SDS-PAGE shows that the level of rrp40-W195R does increase in doa3-1 cells relative to wild-type cells (Figure 7B). The reduced amount of rrp40-W195R in the 600 kDa complex on the native gel is therefore not just due to low levels of this variant. We also find that a greater amount of the rrp40-W195R variant is present in the 600 kDa complex when it is the only copy of Rrp40 in rrp40∆ cells (Figure S5). To complement the native gel analysis of rrp40-W195R, we also examined wild-type and rrp40-W195R proteins in doa3-1 cells by glycerol gradient fractionation (Figure S6). While the majority of wild-type Rrp40 is present in fractions from the middle of the gradient (fractions 7–13; Figure S6A), the majority of the rrp40-W195R is present in the heaviest fraction (fraction 21; Figure S6B). These results suggest the rrp40-W195R variant associates less efficiently with the RNA exosome than wild-type Rrp40.

Figure 7.

The rrp40-W195R variant associates less efficiently than wild-type Rrp40 with the RNA exosome complex in S. cerevisiae cells coexpressing wild-type Rrp40. (A) Unlike wild-type Rrp40, only a low amount of the rrp40-W195R variant in doa3-1 cells migrates as a 600 kDa complex that is consistent with the size of the 11-subunit exosome (Liu et al. 2006) by native gel electrophoresis. In contrast, a similar amount of rrp40-G8A and rrp40-S87A variant compared to wild-type Rrp40 migrates as a 600 kDa complex. Lysates of wild-type and doa3-1 temperature-sensitive proteasome mutant cells expressing Myc-tagged wild-type Rrp40 or variant rrp40 (G8A, S87A, and W195R) were grown at 37° and analyzed by BN-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody to detect Myc-tagged Rrp40 proteins (R/rrp40-Myc) and anti-Pgk1 antibody to detect Pgk1 as a loading control. (B) In the same lysates analyzed by native PAGE in (A), the amount of rrp40-W195R variant in doa3-1 cells is increased and stabilized relative to wild-type cells analyzed by denaturing SDS-PAGE. Lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting anti-Myc antibody to detect Myc-tagged Rrp40 proteins (R/rrp40-Myc), and anti-Pgk1 antibody to detect Pgk1 as a loading control.

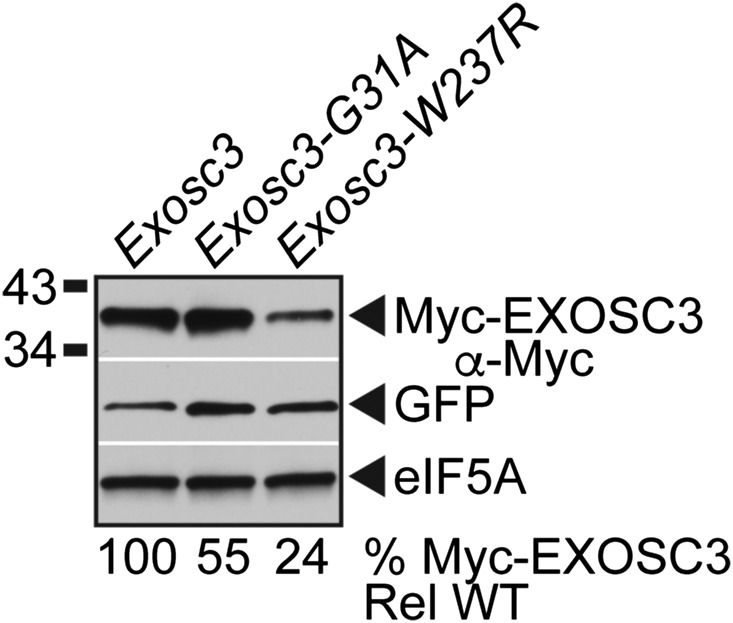

The mouse EXOSC3-W237R variant is expressed at reduced level when coexpressed with wild-type EXOSC3 in neuronal cells

The results presented here have employed budding yeast to assess the functional consequences of amino acid substitutions that occur in EXOSC3 in PCH1b patients. To determine whether the results obtained using budding yeast Rrp40 extend to EXOSC3 to mammalian cells, we generated substitutions in mouse EXOSC3 corresponding to PCH1b-associated substitutions and those analyzed in budding yeast Rrp40: mouse EXOSC3-G31A (human EXOSC3-G31A/yeast rrp40-G8A) and mouse EXOSC3-W237R (human EXOSC3-W238R/yeast rrp40-W195R). Wild-type and variant EXOSC3 proteins were N-terminally Myc-tagged to permit detection. We transfected plasmids that express these mouse EXOSC3 proteins into a mouse N2a neuronal cell line (Klebe and Ruddle 1969), and analyzed the steady-state levels of these Myc-tagged proteins by immunoblotting (Figure 8). To control for transfection efficiency, we employed bicistronic plasmids that coexpress GFP. Notably, the N2a cells express endogenous EXOSC3 as well as the transfected Myc-EXOSC3 proteins. The steady-state level of the mouse EXOSC3-G31A variant was partly reduced (to 55% of wild-type level), whereas the mouse EXOSC3-W237R variant level was reduced fourfold relative to wild-type mouse EXOSC3 (Figure 8). These results suggest that the mouse EXOSC3-W237R variant, corresponding to PCH1b-associated EXOSC3-W238R variant, is unstable in the presence of wild-type EXOSC3, and that mammalian cells have conserved the mechanism to discriminate between wild-type and variant EXOSC3 subunits.

Figure 8.

Variants of murine EXOSC3, corresponding to PCH1b-associated EXOSC3 variants, are expressed at reduced level in a mouse neuronal cell line. The steady-state levels of murine Myc-EXOSC3-G31A or Myc-EXOSC3-W237R variant are decreased relative to wild-type Myc-EXOSC3 in mouse N2a cells. Lysates of mouse N2a cells transfected with bicistronic vectors expressing murine Myc-EXOSC3 or Myc-EXOSC3 variant (G31A; W237R) and GFP were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody to detect Myc-EXOSC3 proteins, and anti-GFP antibody to detect GFP as a transfection control. eIF5A protein was detected with anti-eIF5A antibody as a loading control. Percentage of Myc-EXOSC3 protein relative to GFP and wild-type Myc-EXOSC3 (% Myc-Exosc3 Rel WT) is shown below each lane, and was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Quantitation is for the specific experiment shown, but is representative of multiple experiments.

Discussion

Here, we report results of the functional impact of amino acid substitutions in the S. cerevisiae EXOSC3 ortholog, Rrp40, corresponding to those in PCH1b-associated EXOSC3. As the human EXOSC3 protein does not substitute for the function of the essential S. cerevisiae Rrp40 protein (Brouwer et al. 2001), we generated the amino acid substitutions in Rrp40 corresponding to those present in EXOSC3 in PCH1b patients. Our study reveals that, although a number of PCH1b-associated substitutions alter evolutionarily conserved residues present in the EXOSC3/Rrp40 protein, most of these substitutions do not alter RNA exosome function to a detectable degree in the budding yeast assays employed. However, the W195R substitution in Rrp40, corresponding to W238R in EXOSC3, causes a reproducible reduction in yeast cell growth, RNA exosome function and Rrp40 protein levels. These results provide insight into possible mechanisms of RNA exosome dysfunction, and also suggest that the relative severity of such mutations can be assessed using budding yeast. Notably, PCH1b patients compound heterozygous for EXOSC3 (W238R) and EXOSC3 (G31A) have severe disease and do not live beyond 1 year (Wan et al. 2012). Moreover, no PCH1b patients homozygous for EXOSC3 (W238R) have been reported. Given the impact of the W195R substitution on Rrp40 function, homozygosity for EXOSC3 (W238R) could severely impair RNA exosome function, which could be incompatible with life. Genome sequencing has identified dozens of other nonsynonymous mutations in EXOSC3 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/). Budding yeast could be a useful tool in the analysis of the functional impact of EXOSC3 substitutions and could provide important information for the diagnosis of PCH1b patients and/or genetic counseling of heterozygous carriers.

Most amino acid substitutions in budding yeast Rrp40 corresponding to those in PCH1b-associated EXOSC3 that we examined did not greatly alter RNA exosome function or protein levels in the assays that we employed. This result is not that surprising, given that the RNA exosome is essential for key RNA processing steps such as rRNA maturation (Mitchell et al. 1996) and aberrant RNA turnover (van Hoof et al. 2002), but indicates that these substitutions do not cause complete loss of the Rrp40/EXOSC3 protein.

Very recently, substitutions in a second exosome cap subunit, EXOSC2, corresponding to budding yeast Rrp4, have been linked to a novel syndrome characterized by retinitis pigmentosa, hearing loss, premature aging, and intellectual disability that shows little overlap with PCH1b (Di Donato et al. 2016). As shown in the sequence alignment in Figure S1, one of the residues changed in these EXOSC2 syndrome patients (EXOSC2-G30) is located in the analogous position within the N-terminal domain to the EXOSC3-G31 residue that is changed in PCH1b. Conservation from yeast to human, and between the paralogs EXOSC2 and EXOSC3, suggests that G30 and G31, respectively, are functionally important. However, we tested the function of rrp4 variants corresponding to these syndrome-associated EXOSC2 substitutions (G30V and G198D) as the sole copy of the essential Rrp4 protein, and found that they do not impair cell growth (Figure S7). Thus, like changes in Rrp40 corresponding to those in PCH1b-associated EXOSC3, substitutions in Rrp4 corresponding to those in disease-associated EXOSC2 are unlikely to cause a total loss of protein function, and most likely exert subtle effects on RNA exosome function.

A key question is how defects in the critically important and ubiquitously expressed RNA exosome complex cause tissue-specific defects. This question is particularly intriguing because mutations in the EXOSC3 cap subunit gene affect mostly spinal motor neurons and Purkinje cells (Wan et al. 2012), but mutations in the EXOSC8 core subunit gene also affect oligodendroglia cells (Boczonadi et al. 2014). In addition, mutations in the EXOSC2 cap subunit gene cause a novel syndrome that is not similar to PCH disease (Di Donato et al. 2016). We suggest that PCH-associated substitutions in EXOSC3 or EXOSC8, and disease-related substitutions in EXOSC2, trigger subtle functional changes, perhaps impacting a specific subset of target RNAs. Such target RNAs could be different for the two PCH subtypes and the novel syndrome. For PCH1b, initial identification of the altered target RNAs in budding yeast expressing rrp40 variants by RNA-Seq would be informative. However, subsequent RNA-Seq identification of the disease-relevant target RNAs would likely need to be carried out in neuronal cells. Notably, our results suggest that merely knocking down EXOSC2, 3, or 8 expression in neuronal cells is unlikely to be as informative as examining the effect of specific disease-associated substitutions. Based on our analyses of the rrp40-W195R variant in yeast, initial mammalian studies could focus on the effects of the EXOSC3-W238R substitution variant in neuronal cells.

In contrast to the other substitutions in Rrp40 examined, corresponding to those in PCH1b-associated EXOSC3, we detected altered function for the W195R substitution in Rrp40. The presence of a bulky hydrophobic residue at this position seems to be required, as rrp40-W195R expression in rrp40∆ cells conferred a growth defect and an increase in the levels of exosome RNA targets at 37° when expressed as the sole copy of Rrp40, but cells expressing rrp40-W195F cells did not show a growth defect. Notably, the steady-state level and stability of the rrp40-W195R variant in rrp40Δ cells was reduced compared to wild-type Rrp40 at 37° (Figure 4, A and B) and at 30° (Figure 4A and Figure S4). We conclude that the rrp40-W195R substitution makes the Rrp40 protein less stable, leading to a decreased Rrp40 protein level and impaired production and/or function of the RNA exosome.

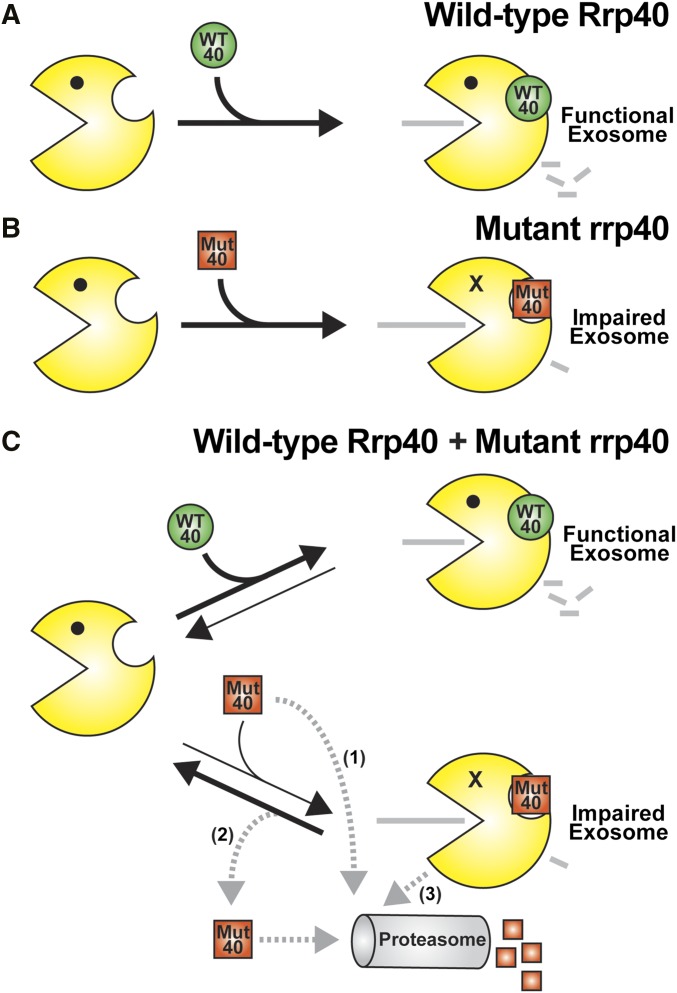

Our studies of the rrp40-W195R and -195A variants yielded a surprising finding that could have implications for understanding RNA exosome assembly and quality control (Figure 9). In rrp40∆ cells that express only the rrp40-W195R or –W195A variant (Figure 9B), the steady-state level of the rrp40 variant is partly reduced (63–65%) compared to wild-type Rrp40 at 30° (Figure 4A). However, in cells that express both wild-type Rrp40 and rrp40-W195R or –W195A (Figure 9C), the steady-state level of the rrp40 variant is greatly decreased (24–30%) relative to wild-type Rrp40 at 30° (Figure 5A). In addition, the stability of the rrp40-W195R variant in cells coexpressing wild-type Rrp40 is greatly decreased (t1/2 ∼6 min) compared to cells that express only rrp40-W195R (t1/2 ∼116 min) at 30° (Figure 6B and Figure S4). This finding suggests a model (Figure 9C) where cells assemble functional RNA exosome complex by distinguishing between wild-type Rrp40 and rrp40 variant. In support, we find that the rrp40-W195R variant does not associate as efficiently with the exosome complex in cells coexpressing wild-type Rrp40 compared to cells that express only rrp40-W195R (Figure 7 and Figure S6).

Figure 9.

Model for exosome assembly and function. (A) When cells express wild-type Rrp40 (WT 40) as the only copy of Rrp40, the exosome assembles properly to produce a fully functional exosome. (B) When cells express variant rrp40-W195R (Mut 40) as the only copy of Rrp40, the exosome shows impaired function as evidenced by a modest decrease in cell growth, altered levels of exosome target transcripts, and subunit instability. (C) When cells express both wild-type Rrp40 (WT 40) and variant rrp40-W195R (Mut 40), the rrp40-W195R is highly unstable and degraded rapidly in a proteasome-dependent manner. As indicated by the black arrows depicting RNA exosome complex assembly and disassembly, the rrp40-W195R protein (Mut 40) could be assembled into the RNA exosome less efficiently than the wild-type Rrp40 (WT 40), or the exosome complex assembled with rrp40-W195R (Mut 40) could be disassembled more rapidly than the exosome containing wild-type Rrp40. Importantly, reduced association of rrp40-W195R with the exosome in cells expressing wild-type Rrp40 is supported by native gel and glycerol gradient analysis. Several possible routes for degradation of rrp40-W195R (Mut 40) exist (gray dashed arrows): (1) Mut 40 subunit could be degraded directly without ever being incorporated into the RNA exosome; (2) Mut 40 subunit that results from disassembly of the exosome complex could be targeted for degradation; or (3) the entire RNA exosome assembled with Mut 40 could be targeted for degradation. Further studies will be required to distinguish between these possible mechanisms for rapid, proteasome-mediated turnover of the rrp40 variant.

Several possible mechanisms for exosome assembly could explain how cells show preference for a wild-type exosome subunit as compared to a variant subunit. Although exosome assembly factors have not yet been identified, there could be chaperones that help to ensure assembly of an optimal exosome complex. Like the proteasome, these chaperones could control the assembly of specific exosome subcomplexes or regulate the order in which specific exosome subunits or subcomplexes associate (Tomko and Hochstrasser 2013). In such a scenario, the rate of assembly of the variant subunit into the RNA exosome might be decreased relative to assembly of a wild-type subunit (Figure 9C). An alternative possibility is that assembly of Rrp40, and possibly other subunits, into the RNA exosome could be reversible at a significant rate (Figure 9C). The defects in interactions with other RNA exosome subunits caused by PCH1b-associated substitutions could increase the rate of disassembly from the complex. Thus, in the presence of wild-type Rrp40, the variant rrp40 subunit could be replaced and subsequently degraded. Further studies will be required to understand how the RNA exosome can apparently discriminate between wild-type and variant subunits.

Very little is known about RNA exosome assembly and quality control. However, a previous study of the Trypanosoma brucei RNA exosome subunits, TbRRP4 and TbRRP45, showed that high level expression of tagged TbRRP4 or TbRRP45 led to proteasome-dependent turnover of the corresponding endogenous exosome subunit (Estevez et al. 2003). Based on this latter study, and other previous work showing that neither TbRRP4 nor TbRRP45 was detected independent of fractions containing the RNA exosome complex in glycerol density gradient analysis (Estevez et al. 2001), these authors proposed that, when these subunits are not incorporated into the RNA exosome, they are subject to rapid degradation. Another finding consistent with altered RNA exosome subunit stoichiometry leading to subunit turnover comes from the recent study of EXOSC8 mutations in PCH1c patients (Boczonadi et al. 2014). This latter study reported that EXOSC8 mutations (or EXOSC8 knockdown) that reduced the steady-state level of EXOSC8 protein led to a concomitant decrease in the level of EXOSC3 protein (Boczonadi et al. 2014). Consistent with these observations on the T. brucei and human RNA exosome, our results in yeast and mammalian cells showing that rrp40/EXOSC3 variant levels are reduced in the presence of wild-type subunit suggest that a conserved mechanism exists to ensure formation, and/or maintenance, of optimal RNA exosome complex.

In summary, the work presented here provides a rapid screening approach that exploits budding yeast to identify the most functionally impaired amino acid changes linked to PCH1b disease. In addition, our analyses of rrp40 variants provide insight into a possible mechanism for RNA exosome assembly and quality control that could be impacted by the PCH1b-associated substitutions.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Corbett and van Hoof laboratories for critical discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grants (GM058728) to A.H.C. and (GM099790) to A.v.H. S.B. was supported by NIH R25 GM099644. B.A. was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Science Education Program award #52006923 to Emory University. J.C.V. was supported by a summer research stipend from The University of Texas Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at Houston. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Emory University, or The University of Texas.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: M. Hampsey

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.116.195917/-/DC1.

Literature Cited

- Adams A., Gottschling D. E., Kaiser C. A., Stearns T., 1997. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Agamy O., Ben Zeev B., Lev D., Marcus B., Fine D., et al. , 2010. Mutations disrupting selenocysteine formation cause progressive cerebello-cerebral atrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87: 538–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akizu N., Cantagrel V., Schroth J., Cai N., Vaux K., et al. , 2013. AMPD2 regulates GTP synthesis and is mutated in a potentially treatable neurodegenerative brainstem disorder. Cell 154: 505–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allmang C., Petfalski E., Podtelejnikov A., Mann M., Tollervey D., et al. , 1999. The yeast exosome and human PM-Scl are related complexes of 3′ → 5′ exonucleases. Genes Dev. 13: 2148–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle A., Tanay A., Bitincka L., Shamir R., O’Shea E. K., 2006. Quantification of protein half-lives in the budding yeast proteome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 13004–13009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancheri R., Cassandrini D., Pinto F., Trovato R., Di Rocco M., et al. , 2013. EXOSC3 mutations in isolated cerebellar hypoplasia and spinal anterior horn involvement. J. Neurol. 260: 1866–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boczonadi V., Muller J. S., Pyle A., Munkley J., Dor T., et al. , 2014. EXOSC8 mutations alter mRNA metabolism and cause hypomyelination with spinal muscular atrophy and cerebellar hypoplasia. Nat. Commun. 5: 4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau F., Basquin J., Ebert J., Lorentzen E., Conti E., 2009. The yeast exosome functions as a macromolecular cage to channel RNA substrates for degradation. Cell 139: 547–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer R., Allmang C., Raijmakers R., van Aarssen Y., Egberts W. V., et al. , 2001. Three novel components of the human exosome. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 6177–6184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. T., Bai X., Johnson A. W., 2000. The yeast antiviral proteins Ski2p, Ski3p, and Ski8p exist as a complex in vivo. RNA 6: 449–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde B. S., Namavar Y., Barth P. G., Poll-The B. T., Nurnberg G., et al. , 2008. tRNA splicing endonuclease mutations cause pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Nat. Genet. 40: 1113–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. S., Mitchell P., 2010. Rrp6, Rrp47 and cofactors of the nuclear exosome. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 702: 91–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner K., Wenig K., Hopfner K. P., 2005. Structural framework for the mechanism of archaeal exosomes in RNA processing. Mol. Cell 20: 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman M. A., Lawrence M. S., Keats J. J., Cibulskis K., Sougnez C., et al. , 2011. Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature 471: 467–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Hochstrasser M., 1996. Autocatalytic subunit processing couples active site formation in the 20S proteasome to completion of assembly. Cell 86: 961–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]