Pierobon and Lennon-Duménil highlight recent findings on how the mechanical properties of membranes affect uptake of surface-tethered antigen by B lymphocytes.

Abstract

Using an exquisite cell imaging approach based on DNA nanosensors, Spillane and Tolar (2016. J. Cell Biol. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201607064) explore how the physical properties of antigen-presenting cell surfaces affect how B cells internalize surface-tethered antigens. Soft and flexible surfaces promote mechanical force-mediated antigen extraction, whereas stiff surfaces lead to enzyme-mediated antigen release before subsequent internalization.

Endocytosis requires deformation of cell membranes and cytoskeleton remodeling (Doherty and McMahon, 2009; Johannes et al., 2015). When we think about the energy requirements of these processes, it is natural to assume that membrane mechanics are highly relevant but how they contribute to endocytosis in physiological contexts remains poorly investigated. In this issue, Spillane and Tolar address this question by studying how the mechanical properties of cellular membranes affect how B lymphocytes acquire antigen from the surface of neighboring cells. B cells that recognize antigen via their B cell receptor (BCR) internalize the antigen by endocytosis (Batista and Neuberger, 2000; Junt et al., 2007; Suzuki et al., 2009). Once internalized in B cells, antigens are degraded into antigenic peptides that are loaded onto major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and presented to primed T lymphocytes. This cooperative process between B and T cells that recognize the same antigen controls the subsequent formation of a germinal center of proliferating, activated B cells in lymphoid tissue and drives the production of high-affinity antibodies and a protective immune response (Mitchison, 2004). It is therefore important to unravel the primary rules that govern the endocytosis of surface-tethered antigen by B cells.

How does antigen extraction occur? Pioneering work from Batista and Neuberger (1998) showed that it occurs at the synapse that forms between the B lymphocyte and the antigen-presenting cell (APC). While performing these experiments, Batista et al. (2001) observed that B cells could eventually internalize entire pieces of APCs, leading them to suggest that antigen extraction might involve major mechanical processes. However, it took more than ten years to obtain a direct demonstration of the existence of this mechanical component. In 2013, Natkanski et al. (2013), inspired by early work on clathrin-coated pits (Moore et al., 1987), used plasma membrane sheets (PMS), as opposed to artificial planar lipid bilayers (PLB), to study antigen extraction by B cells. They showed that antigen extraction was far more efficient on PMS than PLB or glass and that it occurred through mechanical pulling by the B cell on BCR–antigen complexes, which promoted their internalization in clathrin-coated vesicles. The reason that antigen extraction was inefficient in PLB remained unclear at that time. Spillane and Tolar (2016) now suggest that this is because of the distinct physical properties exhibited by these two experimental systems.

In the meantime, an alternative mechanism for antigen extraction by B lymphocytes involving enzymatic antigen degradation at the synapse before endocytosis was identified (Yuseff et al., 2011).While studying the trafficking of MHC class II–containing lysosomes in B cells stimulated by antigens immobilized on polystyrene beads, Yuseff et al. (2011) observed that these vesicles were recruited and secreted at the B cell synapse where they released hydrolases that facilitated antigen capture. Lysosome recruitment at the interface between B cells and antigen-presenting cells was shown to result from centrosome reorientation. It was proposed that this enzyme-mediated mechanism couples the extraction of surface-tethered antigens to their processing for presentation onto MHC class II molecules in B lymphocytes (Yuseff et al., 2011, 2013; Reversat et al., 2015). Whether the mechanical and biochemical pathways of antigen extraction by B cells occurred concomitantly or, on the contrary, were exclusive, remained unanswered to date.

Spillane and Tolar (2016) address this question by using DNA-based nanosensors that allow antigens extracted by B cells through enzymatic degradation versus mechanical disruption to be distinguished. They found that the two mechanisms are used by B lymphocytes in a mutually exclusive manner and that the physical properties imposed by the APC surfaces on B cells determines which mechanism is used. Nondeformable rigid surfaces such as PLB promote antigen extraction through hydrolysis, whereas deformable flexible surfaces such as PMS lead to mechanical antigen extraction (Fig. 1). Mechanical extraction is the dominant antigen internalization mechanism observed in two types of APCs: follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) and conventional dendritic cells (DCs). However, if antigens fail to be mechanically internalized, B cells can switch to enzymatic degradation. In contrast, if mechanical extraction is successful, even if only partially, lysosomes are no longer recruited to the synapse and antigen extraction through hydrolysis is therefore inhibited. Whether the inhibition of lysosome recruitment at the synapse merely results from the internalization of BCR complexes, which would lead to detachment of B cells from the antigen-presenting surface, or if it involves additional inhibitory mechanisms is an interesting question. The surprising finding that mechanical internalization of a small fraction of surface-tethered antigens is sufficient to prevent enzymatic antigen extraction suggests that an active inhibitory mechanism is at work.

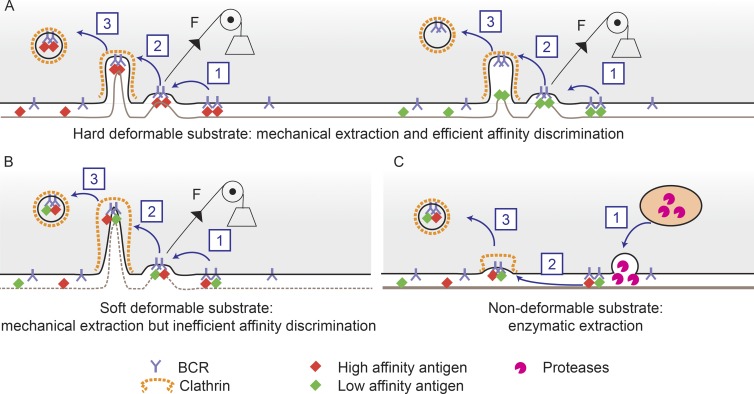

Figure 1.

Antigen extraction by B cells depends on the physical properties of the antigen-coated surface. (A) On a rigid deformable substrate, antigens are recognized by the BCR and gathered into microclusters. (1) Mechanical forces pull on antigen–BCR complexes. (2 and 3) High-affinity antigens are internalized into clathrin-coated pits (2), whereas low-affinity antigens detach from the BCR upon tension and only the BCR is internalized (3): Mechanical energy is therefore used for affinity discrimination. (B) On a flexible and deformable substrate, antigens are recognized by the BCR and internalized as described in A. However, because the softer substrate allows a higher degree of deformation, affinity discrimination is less stringent. (C) On nondeformable antigens (or very stiff substrates), such as plastic or glass, B cells secrete hydrolases after polarization of lysosomes at the synapse (1), this promotes antigen release from the substrate (2) and subsequent internalization (3) of soluble antigens.

The findings by Spillane and Tolar (2016) have important immunological implications. In their previous work they had shown that low-affinity antigens are not efficiently internalized through mechanical pulling as the association of low-affinity antigen with the BCR is disrupted by the forces generated by mechanical pulling, whereas interactions between high-affinity antigens and the BCR resist such forces (Natkanski et al., 2013). Remarkably, this new study suggests that this phenomenon, referred to as “affinity discrimination,” depends on the physical properties of the APC surface. In FDCs, affinity discrimination is high as their surface, which is more rigid and less deformable than the surface of DCs, resists mechanical pulling by B cells. In contrast, affinity discrimination is low when antigens are exposed on DCs, as their flexible surface deforms in response to mechanical forces exerted by B lymphocytes. These findings imply that antigen presentation by different APCs may lead to differential antigen internalization and therefore to distinct B cell responses in terms of antibody production. Indeed, FDCs are the main APCs in the context of T–B cooperation in the germinal center reaction, during which higher affinity BCRs (and thus antibodies) are selected (Batista and Harwood, 2009). The contribution of conventional DCs to presentation of antigens to B cells in vivo is not clearly defined. However, subcapsular sinus macrophages can present surface-tethered antigens to naive B lymphocyte at the periphery of follicles; whether or not these APCs control affinity discrimination remains to be investigated. Interestingly, macrophages were recently reported to be among the stiffer immune cells (Bufi et al., 2015), suggesting that they might be effective at helping B cells selectively capture high-affinity antigens.

How are the mechanical forces controlling antigen uptake produced? Previous studies by Natkanski et al. (2013) identified the actin-based motor protein Myosin II as a requirement for mechanical antigen extraction. However, how Myosin II generates these forces remains to be established. From a cell biological perspective, the work by Spillane and Tolar (2016) raises the fundamental question of how mechanical forces in general contribute to endocytosis in vivo. At least part of the molecular complexes that can be internalized by cells in tissues are likely to exist in an immobilized form, for example, bound to cell surfaces or to the extracellular matrix. Are Myosin II–dependent forces generally used for receptor-mediated endocytosis in the complex environment of tissues, although it has been shown to be dispensable in most forms of endocytosis ex vivo? If yes, how is this process modulated by the mechanical properties of the cell environment? We are confident that the increasing effort of cell biologists to productively interact with biophysicists will help address these physiologically relevant questions in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This work was supported by funding from the city of Paris, the H2020 European Research Council (Strapacemi 243103), the DCBIOL Labex (ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02-PSL and ANR-11-LABX-0043), the Association Nationale pour la Recherche et de la Technologie (ANR-09-PIRI-0027-PCVI), and the InnaBiosanté foundation (Micemico).

References

- Batista F.D., and Harwood N.E.. 2009. The who, how and where of antigen presentation to B cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9:15–27. 10.1038/nri2454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista F.D., and Neuberger M.S.. 1998. Affinity dependence of the B cell response to antigen: a threshold, a ceiling, and the importance of off-rate. Immunity. 8:751–759. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80580-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista F.D., and Neuberger M.S.. 2000. B cells extract and present immobilized antigen: implications for affinity discrimination. EMBO J. 19:513–520. 10.1093/emboj/19.4.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista F.D., Iber D., and Neuberger M.S.. 2001. B cells acquire antigen from target cells after synapse formation. Nature. 411:489–494. 10.1038/35078099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bufi N., Saitakis M., Dogniaux S., Buschinger O., Bohineust A., Richert A., Maurin M., Hivroz C., and Asnacios A.. 2015. Human primary immune cells exhibit distinct mechanical properties that are modified by inflammation. Biophys. J. 108:2181–2190. 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.03.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty G.J., and McMahon H.T.. 2009. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78:857–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes L., Parton R.G., Bassereau P., and Mayor S.. 2015. Building endocytic pits without clathrin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16:311–321. 10.1038/nrm3968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junt T., Moseman E.A., Iannacone M., Massberg S., Lang P.A., Boes M., Fink K., Henrickson S.E., Shayakhmetov D.M., Di Paolo N.C., et al. 2007. Subcapsular sinus macrophages in lymph nodes clear lymph-borne viruses and present them to antiviral B cells. Nature. 450:110–114. 10.1038/nature06287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison N.A. 2004. T-cell–B-cell cooperation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:308–312. 10.1038/nri1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M.S., Mahaffey D.T., Brodsky F.M., and Anderson R.G.W.. 1987. Assembly of clathrin-coated pits onto purified plasma membranes. Science. 236:558–563. 10.1126/science.2883727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natkanski E., Lee W.Y., Mistry B., Casal A., Molloy J.E., and Tolar P.. 2013. B cells use mechanical energy to discriminate antigen affinities. Science. 340:1587–1590. 10.1126/science.1237572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reversat A., Yuseff M.I., Lankar D., Malbec O., Obino D., Maurin M., Penmatcha N.V., Amoroso A., Sengmanivong L., Gundersen G.G., et al. 2015. Polarity protein Par3 controls B-cell receptor dynamics and antigen extraction at the immune synapse. Mol. Biol. Cell. 26:1273–1285. 10.1091/mbc.E14-09-1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane K.M., and Tolar P.. 2016. B cell antigen extraction is regulated by physical properties of antigen-presenting cells. J. Cell Biol. 10.1083/jcb.201607064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K., Grigorova I., Phan T.G., Kelly L.M., and Cyster J.G.. 2009. Visualizing B cell capture of cognate antigen from follicular dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 206:1485–1493. 10.1084/jem.20090209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuseff M.I., Reversat A., Lankar D., Diaz J., Fanget I., Pierobon P., Randrian V., Larochette N., Vascotto F., Desdouets C., et al. 2011. Polarized secretion of lysosomes at the B cell synapse couples antigen extraction to processing and presentation. Immunity. 35:361–374. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuseff M.-I., Pierobon P., Reversat A., and Lennon-Duménil A.-M.. 2013. How B cells capture, process and present antigens: A crucial role for cell polarity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13:475–486. 10.1038/nri3469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]