Abstract

Objectives

Suboptimal medication adherence for infectious diseases such as tuberculosis (TB) results in poor clinical outcomes and ongoing infectivity. Directly observed therapy (DOT) is now standard of care for TB treatment monitoring but has a number of limitations. We aimed to develop and evaluate a smartphone-based system to facilitate remotely observed therapy via transmission of videos rather than in-person observation.

Design

We developed an integrated smartphone and web-based system (Mobile Interactive Supervised Therapy, MIST) to provide regular medication reminders and facilitate video recording of pill ingestion at predetermined timings each day, for upload and later review by a healthcare worker. We evaluated the system in a single arm, prospective study of adherence to a dietary supplement. Healthy volunteers were recruited through an online portal. Entry criteria included age ≥21 and owning an iOS or Android-based device. Participants took a dietary supplement pill once, twice or three-times a day for 2 months. We instructed them to video each pill taking episode using the system.

Outcome

Adherence as measured by the smartphone system and by pill count.

Results

42 eligible participants were recruited (median age 24; 86% students). Videos were classified as received—confirmed pill intake (3475, 82.7% of the 4200 videos expected), received—uncertain pill intake (16, <1%), received—fake pill intake (31, <1%), not received—technical issues (223, 5.3%) or not received—assumed non-adherence (455, 10.8%). Overall median estimated participant adherence by MIST was 90.0%, similar to that obtained by pill count (93.8%). There was a good relationship between participant adherence as measured by MIST and by pill count (Spearmans rs 0.66, p<0.001).

Conclusions

We have demonstrated the feasibility, acceptability and accuracy of a smartphone-based adherence support and monitoring system. The system has the potential to supplement and support the provision of DOT for TB and also to improve adherence in other conditions such as HIV and hepatitis C.

Keywords: adherence, Directly Observed Therapy, Smartphone

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our system is novel and was developed to be simple to use and relevant to patients with TB requiring directly observed treatment.

We tested the system for monitoring adherence at a range of pill frequencies (up to three times daily).

We tested for robustness against deliberate deception.

Initial technical problems with the system which reduced observed adherence in some individuals.

We tested the system in a predominantly young and technologically literate cohort, which, while ideal for identifying and reporting initial problems during the pilot stage, is not representative of a patient cohort.

Background

Non-adherence to medications is one of the main causes of suboptimal patient outcomes.1 For treatment of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), HIV and hepatitis C, non-adherence to medication reduces the patients' chances of recovery but also increases the risk of the development of drug resistance and the spread of disease in the community. These public health risks are considered to justify a more invasive approach to supporting and monitoring adherence, in contrast to other conditions where non-adherence poses risks that are mainly limited to the individual.

To address the issue of poor adherence for TB, the WHO developed directly observed treatment (DOT).2 This initiative primarily involves direct observation of adherence, which usually requires a patient to travel to a clinic daily. Limitations of this approach include the heavy burden it places on already overstretched health systems, the time and inconvenience for patients that can lead to employment challenges, loss of earnings and mental health problems;3 4 and frequent journeys on public transport which potentially expose other commuters to TB.5 6 Similar approaches to observed therapy have been suggested for HIV-infected individuals who have adherence challenges—in the past this has not been framed in terms of public health risk to the community, but as the benefits of virological suppression on HIV disease transmission have become more clearly established (and indeed now form the cornerstone of HIV public health policy), systematic programme-based adherence support approaches may also become more relevant for HIV.7–9

Since the introduction of DOT more than 20 years ago, mobile phone ownership has increased from 34 million subscriptions globally to more than 7 billion.10 11 The most rapid growth in the first quarter of 2016 was seen in India, Myanmar and Indonesia.10 Globally, smartphones now account for 50% of all mobile phone subscriptions and 80% of all new subscriptions. In middle-income countries such as Peru, Kenya, Philippines and Russia, one to two out of every four people own a smartphone.11 These figures are increasing rapidly. Smartphone subscriptions in Africa are predicted to increase by more than 200% by 2021.10 Smartphones are capable of recording and transmitting high-quality video to distant healthcare facilities, with potential benefits for public health that have not yet been fully exploited.

We aimed to develop and evaluate a smartphone-based system to facilitate remote directly observed therapy via transmission of videos rather than in-person observation.

Methods

Design and development of the system

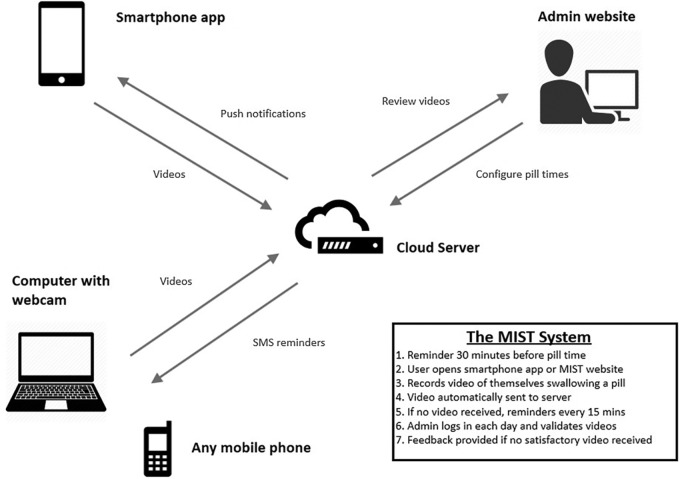

The system, which we called ‘Mobile Interactive Supervised Therapy’ (MIST), comprises integrated web and smartphone-based components (figure 1). The web component of the system allows the administrator to set the required time(s) of pill-taking each day, selected according to the frequency of therapy and patient preferences. Although a common time is usually set for all days of the week, the system allows this to be set to different times each day (eg, different on weekdays and weekends) and could be adjusted if the patient’ preference changes during the course of treatment. Once set, the system sends pill reminder notifications (via SMS or push service) to the patient's mobile phone 30 min prior to each scheduled pill time, with repeated reminders every 15 min continuing until the patient uses their smartphone to transmit a video of themselves taking the pill or 1 hour has passed since the planned time of ingestion. The system stores uploaded videos with a time and date stamp on a secure cloud server linked only to a subject number. Following successful upload videos are automatically deleted from the phone. The administrator web portal displays all active patients and shows whether a video has been received or not for the expected pill times, so that missing videos can be identified rapidly. To minimise the time required for review, multiple videos can be viewed on a single screen, with each step of each video adjusted automatically to take the same amount of time (sped up or slowed down as necessary) so that each step in each video occurs on the screen simultaneously. Previously submitted videos can also be reviewed if necessary.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the components of MIST system. MIST, Mobile Interactive Supervised Therapy.

To record and transmit the video, the patient starts the smartphone application and follows the on-screen instructions that guide them through a series of steps that are recorded by the phone video camera: holding the pill close to the camera, swallowing it with a sip of water and putting out the tongue to show that the pill is no longer present. Having completed these steps, the patient clicks stop and the video is uploaded automatically to the server. A back-up system was available in which the patient could upload and submit videos at the appropriate time via the MIST website using a personal computer with a webcam. Videos can only be uploaded from within the application, immediately after recording, so there is no ability to upload a previously recorded video.

Evaluation of the system

Healthy volunteers were recruited by placing advertisements on an online portal for students and staff at the National University of Singapore. Inclusion criteria were age 21 or over and owning a compatible mobile device (iPhone or iPad or Android-based smartphone). Participants were excluded if they had an allergy or contraindication to the study pills. The study was approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

There were two study visits. At the initial visit, participants were asked about their prior technical experience with computers and smartphones using a seven-point Likert scale (1: ‘none’ to 7: ‘proficient’), medication history and history of medication adherence (proportion of previous medication courses fully completed (1: ‘none’ to 7: ‘all’)). Each participant was provided with a supply of test pills (either multivitamins (Webber Naturals, Coquitlam, Canada) or resveratrol 250 mg (Biovea, Singapore), a dietary supplement; the latter was used in preference when multiday dosing was being tested) for the 2-month duration of the intervention. Cohort allocation was sequential. The initial participants were asked to take a pill once daily. After the system had been evaluated and was stable for once-daily dosing (based on the incidence of technical problems preventing video upload falling consistently below 10% of pill taking episodes), the subsequent cohort of participants were asked to take pills two times per day and the final cohort three times daily at mutually agreed times.

The MIST application was installed onto the participant's smartphone, and they were given a demonstration on how to use the system to submit videos. They were asked to submit videos for all scheduled pill taking episodes. To test the ability of the system to detect deliberate deceit, all participants were also asked to try to circumvent the system once or twice during the 2-month study, at a time and in a manner of their choosing, by uploading a video where they appeared to take a pill but did not actually swallow their prescribed pill. They were given contact details of an independent researcher and asked to inform them when they had sent a sham video. The independent researcher kept a list and provided this to the study team at the completion of the study.

A research nurse accessed the MIST web portal at approximately the same time each day to review all videos submitted within the preceding 24-hour period. Videos submitted over a weekend were reviewed on the subsequent working day. If videos were found to be missing for three consecutive timeslots, the research nurse telephoned the participant to determine the cause. Participants were also given the contact number of the research nurse and asked to report any problems experienced with the system. After discussion with the participant, reasons for missing videos were categorised as either a technical problem or non-adherence. When participant non-adherence was detected, participants were counselled and a change in scheduled pill time was offered where this might address the underlying problem. Reported technical problems were rectified as quickly as possible, but the study was not interrupted.

At the final study visit, participants were asked to return their pill bottle and a pill count was performed. Participants were asked to evaluate whether they felt the system helped them adhere to their course of pills, using a seven point Likert scale (1: ‘strongly disagree’ to 7: ‘strongly agree’).

Sample size and analysis

A target sample size of 50 participants was selected based on pragmatic considerations of feasibility of recruitment and available resources and was thought likely to provide reasonable experience with the system. All analyses were based on the 2-month period of follow-up. Videos were classified as received—confirmed pill intake, received—uncertain pill intake (eg, due to poor lighting conditions), received—fake pill intake (eg, ingestion of a piece of candy), not received—technical issues (considered as a dose taken) or not received—assumed non-adherence (considered as a dose not taken).

Adherence for each individual was calculated in two ways. Adherence by pill count was calculated by ((pills dispensed−pills returned)/pills dispensed)×100. Adherence measured by the MIST system was calculated by ((videos received confirming pill intake+videos not received due to technical problems)/videos expected)×100. Where patients reported technical issues that prevented them recording or uploading the video, we counted this as an episode of adherence (because they were instructed to take the pill in the event they could not record the video, and they would have taken the pill prior to attempting to upload). Correlation was assessed using Spearman rank coefficient. A one-way ANOVA was performed to assess differences in adherence at increasing pill frequencies. All analyses were carried out using SPSS V.21.

Results

We assessed 48 healthy volunteers for participation, of which 42 met criteria and were recruited (median age 24 (range 22–40); 17 (45%) male; 36 (86%) students). Three were taking multivitamin supplements regularly prior to the study (changed to study multivitamins for the duration of the trial), and none were on any other medications. Eleven had taken medication courses previously, with a high self-reported adherence score (median 6 out of a scale of 7; range 4–7). Participants also reported high technical skill level with computers (median 6, range 5–6) and smartphones (median 6, range 4–6) on the same scale. The main device used for accessing MIST was Apple iPhone in 11, Android-based smartphone in 26 and a personal computer with webcam in 5. Twenty-three received a once a day regimen, 10 twice a day and 9 three times a day. Twenty-eight received resveratrol, and the remainder received a combination of resveratrol and multivitamins.

Videos were classified into one of five categories (see table 1): received—confirmed pill intake (3475, 82.7% of the 4200 videos expected), received—uncertain pill intake (16/4200, <1%), received—fake pill intake (31/4200, <1%), not received—technical issues (223/4200, 5.3%) or not received—assumed non-adherence (455/4200, 10.8%). Reasons for non-adherence were often related to illness or overseas travel (participants could still take the pill and use the system overseas but often chose not to do so because of increased data charges). Participants reported sending 40 videos mimicking deliberate non-adherence, of which 28 were accurately identified by the observer, 12 were missed and 3 normal videos were incorrectly identified as showing deliberate non-adherence. The reported techniques for faking pill intake that were not detected included using an opaque cup into which the participant spat the pill while taking a sip of water and holding the pill under the tongue.

Table 1.

Overall numbers of expected videos received or not received (left column) and median proportion per patient (right column)

| Video outcomes |

||

|---|---|---|

| Videos expected (n=4200) | Total number in each category (proportion of all expected videos, %) | Median proportion per patient (%), (range) |

| Video received (n=3522) | ||

| Confirmed pill ingestion | 3475 (82.7) | 86.7 (41.1–99.2) |

| Uncertain pill ingestion | 16 (<1) | 0.0 (0–6.7) |

| Fake ingestion | 31 (<1) | 0.8 (0–5.0) |

| Video not received (n=678) | ||

| Assumed non-ingestion | 455 (10.8) | 8.3 (0–51.7) |

| Technical issue reported | 223 (5.3) | 3.3 (0–31.7) |

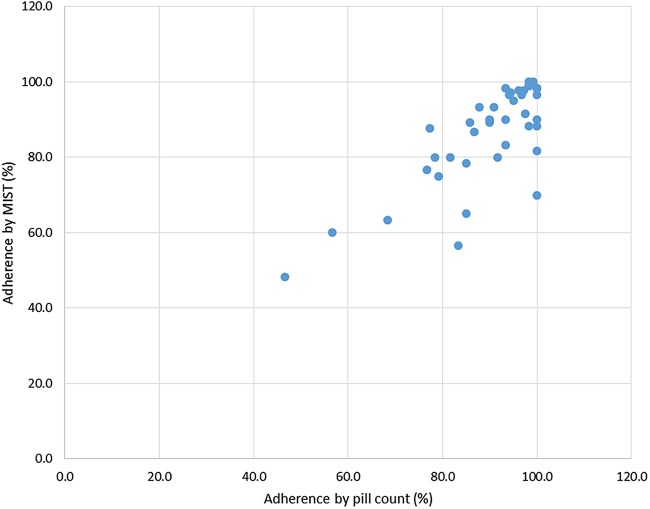

Overall the median estimated participant adherence by MIST was 90.0% (range 48.3–100%), similar to that obtained by pill count (93.8%, range 46.7–100.0%). There was a good relationship between participant adherence as measured by MIST and adherence by pill count (Spearmans correlation coefficient rs 0.66, p<0.001, see figure 2). Overall adherence by MIST was classified as ≥90% in 22 (52%) participants; 80–90% in 11 (26%) and <80% in 9 (21%); similar to the proportions obtained by pill count for these three categories (28 (66.7%), 7 (16.7%) and 7 (16.7%), respectively). There was no significant difference observed in adherence between once, twice or three times a day pill intake, measured by MIST (p=0.134), or pill count (p=0.414) (one-way ANOVA). Thirty per cent of technical problems were attributable to four individuals.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of adherence by MIST versus adherence by pill count. MIST, Mobile Interactive Supervised Therapy.

The system was perceived to be beneficial by the participants (a median score of 6 (range 4–7) of 7, when asked whether the system helped them to adhere to the course of medication).

Discussion

We developed and tested a smartphone-based system to facilitate remote video observation of pill intake, which can provide real-time information about patient adherence and act to support and enhance adherence. We found that the system was well accepted by participants who all continued the study to the end, and most felt it contributed to their ability to adhere to a 2-month course of pills. It provided images of sufficient quality to allow reliable assessment of pill ingestion by a remote observer and the majority of attempts at cheating the system were detected—those that were not detected could likely be prevented by changes in procedures (such as the use of a transparent drinking cup, or by requiring participants to raise their tongue to show the sublingual area after swallowing). The system also appeared to give accurate estimates of overall adherence in comparison to pill counts. Thus, we have demonstrated feasibility of the system, based on participant acceptability, ease of implementation and accuracy.

The strengths of our study are that we have developed and described a novel system, and one that is relatively simple and easy to replicate. This study demonstrates the principle of the approach which is likely generalisable beyond the specific system we tested. Furthermore, we have tested the system over a substantial period of pill-taking (2 months) and using a range of pill frequencies (from once to three-times daily) that is representative of many clinical scenarios. A small proportion of participants were already taking pills at study entry, but this would be typical of a patient population starting TB treatment and does not affect the validity of the feasibility assessment. The limitations of the study are that we evaluated the system in parallel with continued system development—thus there were some initial technical problems that prevented transmission of videos in a small proportion of occasions, a substantial number of which were attributable to four individuals, likely due to specific phone compatibility issues. We made some assumptions about adherence during these episodes. As the majority of these technical issues occurred at the video upload stage, it was assumed that the pill had already been ingested. Technical issues only accounted for 5% of missed videos, and so alternative assumptions would not substantively alter our conclusions. In spite of initial temporary challenges, participants still maintained their commitment to using the system. Any such system reliant on smartphone connectivity is also likely to have intermittent challenges in patient populations, and it is important to think of this as just one way of adherence support. In some instances, this may need to be supplemented by verbal report, text messages or reversion to standard in-person observation. The study population was mainly young and well educated and technologically aware, which may not be generalisable to the target population in which directly observed therapy is most often used—patients with TB who tend to be from lower socioeconomic strata with fewer years of education.12 As a pilot study, the intervention was limited to a 2-month course of dietary supplements. TB treatment would last at least 6 months and have a higher chance of side effects, both factors which might adversely affect adherence.

This study adds to the limited published literature supporting telemedicine-based approaches to adherence support and monitoring. A number of studies assessed SMS or phone call medication reminders for TB13 14 and HIV.15–20 However, such systems can function as a reminder only and cannot provide a real-time assessment of adherence. Skype and videophones have been tested, but these were limited because a healthcare worker also had to be connected at the allotted time, which is resource heavy, and limits the ability of the patient to choose user friendly pill times.21–23 Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) has also been tested, but the technology is limited by the poor video resolution.24 Our system allows patients to submit high resolution videos, at a time of their choosing, and grants the healthcare worker the flexibility to review all the days' videos in a single session at a time that is convenient. One other published study has been carried out that used a system of smartphone transmission of images and text reminders similar to ours.25 This was shown to be feasible and acceptable in a small group of patients with TB in USA and Mexico, the majority of whom were also comfortable at baseline with various aspects of the technology and so were likely somewhat selected. Taken together, these two studies demonstrate strongly the feasibility of this potential approach to supporting and monitoring adherence. Upscaling such systems will not be without challenges. The network demands of the system are well within those of many countries, even those with limited resources, but the security of such systems must also be taken into consideration. While the videos uploaded to the server are de-identified, there will always exist a small risk that an individual's privacy could be compromised due to malicious activity. This is a challenge that any healthcare system provider must be alert to, and such systems should be appropriately encrypted.

There are several potential advantages of using a system such as MIST for TB compared to standard DOT. It should be noted that DOT is itself lacking in a strong evidence base. Studies from India and Ghana have shown adherence rates with DOT ranging from 63% to 93%,26–28 and a meta-analysis did not identify any significant difference in treatment completion rates between DOT and self-administered treatment.29 A more patient-friendly alternative such as MIST may in itself motivate adherence. Adherent patients could take their pills from their own home or office at a time of their choosing, resulting in less time off work and lost earnings. Second, in some settings MIST has the potential for enhancing adherence compared to standard DOT. MIST has the potential for more frequent monitoring than most DOT programmes, which do not monitor adherence at weekends or more than once a day. In low or middle income countries that are unable to provide in person DOT, video DOT could be deployed at minimal cost, by taking advantage of a resource that an increasing proportion of the population already own. Finally, video DOT allows for more efficient use of healthcare systems. For the majority of patients who would require limited or no support to maintain adherence, DOT represents an unnecessary allocation of healthcare resources. Using the MIST system, non-adherent individuals could be rapidly identified. Resources could then be targeted at providing them the extra support they need, which may include mandating a return to in-person DOT. This individualised approach to patient care would allow for more appropriate allocation of healthcare resources, which may help address the estimated annual funding gap of US$1.6 billion for TB care in low and middle income countries.30

The applicability of the system would extend beyond TB, to any condition where adherence is important, and a short period of intensive adherence monitoring would be beneficial, especially when there is a public health component. The system could provide support during hepatitis C treatment where adherence may be limited by side effects, or during HIV treatment to identify if suboptimal adherence is contributing to a viral rebound.

In summary, we have demonstrated the feasibility and potential for a smartphone-based adherence support and monitoring system. Further work is warranted to test this in diverse patient populations, particularly in TB where DOT is regarded as the standard of care, but is delivered only with variable success. Randomised controlled trials are needed to compare this approach to locally appropriate standard-of-care adherence support and monitoring approaches, preferably evaluating the impact on clinical disease outcomes as well as intermediate measures of adherence.

Acknowledgments

This research is part of Singapore Programme of Research Investigating New Approaches to Treatment of Tuberculosis (SPRINT-TB; http://www.sprinttb.org).

Footnotes

Contributors: JSM and NIP contributed to clinical study concept and design. ZW, BQ, PW and WTO contributed to smartphone system design, development and testing. JSM, YP and ARS involved in patient recruitment and follow-up. All authors involved in manuscript preparation and review.

Funding: This research is supported by National University of Singapore (NUS) under its Start-up grant awarded to NIP.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board, Singapore.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB et al. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2005;1:189–99 (published online first 25 Mar 2008). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. Global Tuberculosis Report 2015: WHO, 2015. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (accessed 16 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee HK, Teo SSH, Barbier S et al. The impact of direct observed therapy on daily living activities, quality of life and socioeconomic burden on patients with tuberculosis in primary care in Singapore. Proc Singapore Healthcare 2016. http://psh.sagepub.com/content/early/2016/07/22/2010105816652148.full.pdf+html [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sagbakken M, Bjune GA, Frich JC. Humiliation or care? A qualitative study of patients’ and health professionals’ experiences with tuberculosis treatment in Norway. Scand J Caring Sci 2012;26:313–23. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horna-Campos OJ, Sanchez-Perez HJ, Sanchez I et al. Public transportation and pulmonary tuberculosis, Lima, Peru. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:1491–3. 10.3201/eid1310.060793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamudio C, Krapp F, Choi HW et al. Public transportation and tuberculosis transmission in a high incidence setting. PLoS One 2015;10:e0115230 10.1371/journal.pone.0115230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505. 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaur AH, Belzer M, Britto P et al. Directly observed therapy (DOT) for nonadherent HIV-infected youth: lessons learned, challenges ahead. AIDS Res Human Retroviruses 2010;26:947–53. 10.1089/aid.2010.0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMahon JH, Medland N. 90-90-90: how do we get there? Lancet HIV 2014;1:e10–1. 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)70017-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ericsson Mobility Report 2016: Ericsson. https://www.ericsson.com/res/docs/2016/ericsson-mobility-report-2016.pdf (accessed 11 Apr 2016).

- 11.Penetration rate of smartphones worldwide by country in 2015: Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/539395/smartphone-penetration-worldwide-by-country/ (accessed 11 Nov 2016).

- 12.Oxlade O, Murray M. Tuberculosis and poverty: why are the poor at greater risk in India? PLoS One 2012;7:e47533 10.1371/journal.pone.0047533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bediang G, Stoll B, Elia N et al. SMS reminders to improve the tuberculosis cure rate in developing countries (TB-SMS Cameroon): a protocol of a randomised control study. Trials 2014;15:35 10.1186/1745-6215-15-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunawararak P, Pongpanich S, Chantawong S et al. Tuberculosis treatment with mobile-phone medication reminders in northern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2011;42:1444–51 (published online first: 2012/02/04). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Shalev N et al. Timed short messaging service improves adherence and virological outcomes in HIV-1-infected patients with suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;58:e113–15. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182359d2a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.da Costa TM, Barbosa BJ, Gomes e Costa DA et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial to assess the effects of a mobile SMS-based intervention on treatment adherence in HIV/AIDS-infected Brazilian women and impressions and satisfaction with respect to incoming messages. Int J Med Inform 2012;81:257–69. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy H, Kumar V, Doros G et al. Randomized controlled trial of a personalized cellular phone reminder system to enhance adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2011;25:153–61. 10.1089/apc.2010.0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mbuagbaw L, van der Kop ML, Lester RT et al. Mobile phone text messages for improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a protocol for an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002954 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safren SA, Hendriksen ES, Desousa N et al. Use of an on-line pager system to increase adherence to antiretroviral medications. AIDS Care 2003;15:787–93. 10.1080/09540120310001618630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simoni JM, Huh D, Frick PA et al. Peer support and pager messaging to promote antiretroviral modifying therapy in Seattle: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;52:465–73 (published online first: 17 Nov 2009). 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b9300c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeMaio J, Schwartz L, Cooley P et al. The application of telemedicine technology to a directly observed therapy program for tuberculosis: a pilot project. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:2082–4. 10.1086/324506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gassanov MA, Feldman LJ, Sebastian A et al. The use of videophone for directly observed therapy for the treatment of tuberculosis. Can J Public Health 2013;104:e272 (published online first: 05 July 2013). 10.17269/cjph.104.3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirsaeidi M, Farshidpour M, Banks-Tripp D et al. Video directly observed therapy for treatment of tuberculosis is patient-oriented and cost-effective. Eur Respir J 2015;46:871–4. 10.1183/09031936.00011015 (published online first: 21 Mar 2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman JA, Cunningham JR, Suleh AJ et al. Mobile direct observation treatment for tuberculosis patients: a technical feasibility pilot using mobile phones in Nairobi, Kenya. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:78–80. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garfein RS, Collins K, Munoz F et al. Feasibility of tuberculosis treatment monitoring by video directly observed therapy: a binational pilot study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015;19:1057–64. 10.5588/ijtld.14.0923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gopi PG, Vasantha M, Muniyandi M et al. Risk factors for non-adherence to directly observed treatment (DOT) in a rural tuberculosis unit, South India. Indian J Tuberc 2007;54:66–70. (published Online First: 20 June 2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danso E, Addo IY, Ampomah IG. Patients’ compliance with tuberculosis medication in Ghana: evidence from a periurban community. Adv Public Health 2015;2015:6 10.1155/2015/948487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandit N, Choudhary SK. A study of treatment compliance in directly observed therapy for tuberculosis. Indian J Community Med 2006;31:241. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volmink J, Garner P. Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD003343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Tuberculosis financing and funding gaps 2013. http://www.who.int/tb/dots/funding_gaps/en/ (accessed 8 Jul 2016).