Abstract

Objective

To determine whether treatment with recombinant human thrombomodulin (rhTM) increases survival among patients with severe septic-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Design

Single-centre, open-label, randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Single tertiary hospital.

Participant

92 patients with severe septic-induced DIC.

Interventions

Patients with DIC scores ≥4, as defined by the Japanese Association of Acute Medicine, were diagnosed with DIC. The envelope method was used for randomisation. The treatment group (rhTM group, n=47) was intravenously treated with rhTM within 24 hours of admission (day 0), and the control group (n=45) did not receive any anticoagulants, except in cases of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Primary and secondary measurements

Data were collected on days 0 (admission), 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 and 10. The primary outcome was survival at 28 and 90 days. The secondary end points comprised changes in DIC scores, platelet counts, d-dimer, antithrombin III and C reactive protein levels, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores. All analyses were conducted on an intent-to-treat basis.

Main results

The 28-day survival rates were 84% and 83% in the control and rhTM groups, respectively (p=0.745, log-rank test). The 90-day survival rates were 73% and 72% in the control and rhTM groups, respectively (p=0.94, log-rank test). Meanwhile, the rates of recovery from DIC (<4) were significantly higher in the rhTM group than in the control group (p=0.001, log-rank test). Relative change from baseline of d-dimer levels was significantly lower in the rhTM group than in the control group, on days 3 and 5.

Conclusions

rhTM treatment decreased d-dimer levels and facilitated DIC recovery in patients with severe septic-induced DIC. However, the treatment did not improve survival in this cohort.

Trial registration number

UMIN000008339.

Keywords: recombinant human thrombomodulin, disseminated intravascular coagulation, sepsis, C-reactive protein, D-dimer, survival

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of recombinant human thrombomodulin (rhTM) for patients with severe sepsis.

rhTM was administered to patients with severe sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which was defined by the Japanese Association of Acute Medicine criteria.

In the control group, no anticoagulant agent was administered.

The primary outcomes were the 28-day and 90-day survival rates.

This study was not a double-blind study.

This study might have presented a difference in the disease severity compared with other studies.

Introduction

Thrombomodulin (TM) is a cell membrane protein expressed on vascular endothelium. Although TM specifically binds to thrombin and inhibits thrombin activity, resulting in anticoagulant action, it also has anti-inflammatory effects and regulates high mobility group box 1 protein activity, a systemic inflammation mediator.1 2

In Japan, a multicentre, prospective, randomised, double-blind, phase III clinical trial3 of recombinant human TM (rhTM), an anticoagulant agent used for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), was performed from 2000 to 2005 and included 234 patients with DIC caused by infection or haematological malignancy. Results showed that although rhTM was associated with a significantly higher DIC resolution rate than heparin, this rate was not significantly different for patients with infection. Further, no difference in 28-day mortality rates of patients with infection or haematological malignancy was observed. The trial had several weaknesses: (1) the primary outcome was the DIC resolution rate, which is a physiological parameter and (2) the control group included patients with DIC who were treated with heparin, which is not the established and standard treatment for sepsis-induced coagulopathy.4

In 2011, Yamakawa et al5 reported a retrospective historical control study with the mortality rate as the primary outcome. Twenty patients with severe septic -induced overt DIC (DIC criteria of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis) who received rhTM between November 2008 and October 2009 were compared with 45 patients who did not receive rhTM between January 2006 and September 2008. The 28-day mortality rate was 25% for the rhTM group versus 47% for the control group. The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, C reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen degradation product (FDP) levels were significantly decreased in the rhTM group, whereas the platelet counts were significantly increased. Further, rhTM treatment also improved respiratory function in patients with sepsis-induced DIC.6

In 2013, a retrospective cohort study adjusted by the propensity score was performed in patients with Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) DIC scores ≥4 who required mechanical ventilation, exhibited multiple organ failure and presented with platelet counts <80 000/mm3. Mortality rates were significantly lower in patients treated with rhTM than in those who did not receive the therapy.7 Although these studies investigated the mortality rate as the primary outcome, they were all retrospective cohort studies, which had certain biases.

In 2013, Vincent et al8 reported a phase IIb double-blind randomised controlled trial (RCT) of rhTM, in which patients who fulfilled the DIC criteria of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis were treated with rhTM or a placebo. Results showed that the 28-day mortality rate tended to be lower in the rhTM group.

It remains unclear whether rhTM is effective in treating patients with severe septic -induced DIC. Therefore, studies with high evidence level are required. Our open-label RCT aimed to investigate whether rhTM treatment increases the 28-day and 90-day survival rates in patients with severe sepsis and JAAM DIC scores ≥4.9

Materials and methods

This single-centre open-label RCT was approved by our institutional ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients or their legal representatives. Patients aged ≥16 years who were transferred to our hospital with severe sepsis were enrolled if their JAAM DIC scores were ≥4 within 24 hours of admission (table 1).9

Table 1.

Japanese Association for Acute Medicine disseminated intravascular coagulation criteria

| Score | |

|---|---|

| Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria | |

| ≥3 | 1 |

| 0–2 | 0 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | |

| <80% or >50% decrease within 24 hours | 3 |

| ≥80 and <120; or 30% decrease within 24 hours | 1 |

| >120 | 0 |

| Prothrombin time | |

| ≥1.2 | 1 |

| <1.2 | 0 |

| Fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products, mg/L | |

| ≥25 | 3 |

| ≥10 and <25 | 1 |

| <10 | 0 |

| Diagnosis | |

| ≥4 points | DIC |

The exclusion criteria were (1) refusal to participate; (2) refusal of aggressive intensive treatment, including haemodialysis, mechanical ventilation and catecholamine administration; (3) emergency surgery within 24 hours of admission; (4) intracranial, pulmonary and/or intestinal haemorrhage; (5) fulminant hepatitis, decompensated liver cirrhosis or other irreversible severe hepatic disease; (6) past history of hypersensitivity to rhTM; and (7) pregnancy or potential pregnancy.

Number of cases and study duration

When our study was planned, the report by Yamakawa et al5 was the only study that investigated the efficacy of rhTM in patients with severe sepsis and sepsis-induced DIC. Therefore, the required number of patients was calculated on the basis of their report. When the observation and follow-up periods were set as 2 years and 90 days, respectively, each group required 47 patients to achieve over 80% power with α=0.05 on a log-rank test. At our institute, 53 and 52 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock who fulfilled the JAAM DIC criteria and who did not undergo emergency surgery within 24 hours after admission were admitted in 2010 and 2011, respectively. The number of patients required for the 2-year study was estimated to be 100. The enrolment period was August 2012 to July 2014.

Randomisation

Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were randomised into the rhTM or control group using the envelope method. Each opaque envelope enclosed a piece of paper specifying either rhTM or control group assignment. We created 50 envelopes for each group assignment, shuffled them and placed them in the designated storage box. Pre-registered co-investigators randomly selected envelopes from the box and treated patients according to group assignment.

Treatment protocol

In both groups, patients were treated under the Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2008 Guideline,10 in which grade I (recommendation as strong) denoted mandatory treatment and grade II (recommendation as weak) required treatment according to the attending physician's judgement.

The attending physician administered rhTM to patients within 3 hours after randomisation. rhTM (380 U/kg) was intravenously administered for 30 min.

Treatment was performed for a maximum of 6 days. When the JAAM DIC score was <4, rhTM treatment was terminated. In the control group, no anticoagulant agent was administered, except in cases of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, for which unfractionated heparin was administered. Unfractionated heparin was also administered to patients in the rhTM group with deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Investigated parameters

The baseline data were collected after randomisation. We obtained the following scores and laboratory data at the time of randomisation: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II), SOFA and JAAM DIC scores; prothrombin time/international normalised ratio (PTINR); and fibrinogen, d-dimer, antithrombin III (ATIII), soluble serum TM and procalcitonin (PCT) levels. We also measured the following scores and data at 24, 48, 72 hours, 5, 7 and 10 days after admission: SOFA and JAAM DIC scores, PTINR, and fibrinogen, d-dimer, and ATIII levels. Other laboratory tests included red blood cell (RBC) and white cell count (WCC) and haemoglobin, albumin, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, electrolyte (Na+, K+ and Cl−) and CRP levels, which were measured at the time of randomisation and 24, 48, 72 hours, 5, 7 and 10 days after admission.

We calculated the relative change from baseline for coagulation and inflammation data and albumin levels using the formula relative change from baseline=((measurement day value−day 0 value)/day 0 value). The relative change from baseline of the SOFA score was calculated using the formula (SOFA score at measurement day−SOFA score at day 0).

We also calculated the number of patients who required mechanical ventilation and the number of ventilator-free days. The number of ventilator-free days was defined as the number of days without assisted mechanical ventilation through day 28. For patients who did not survive up to 28 days, the value was set as 0 days. Requirement or discontinuance of mechanical ventilation was decided by the staff physicians in the emergency department. Online supplementary table S1 shows the criteria for weaning off mechanical ventilation.11 We recorded the number of patients who required catecholamine treatment and its duration, which was performed according to the recommendations of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2008 Guideline, and recorded blood (concentrated RBCs, fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and platelets) and blood derivative administration amounts at 72 hours, 28 and 90 days after admission. We investigated haemorrhage-related side effects and the timing of haemorrhage occurrence.

bmjopen-2016-012850supp_table.pdf (184.5KB, pdf)

Adverse events

Adverse events were monitored prospectively via the daily evening conference. When adverse events occurred, one principle investigator (AH) reported them to our institutional ethics committee.

Adverse events were evaluated for the first 90 days after enrolment. Adverse events that were urgently reported were as follows: (1) death during the study, (2) life-threatening haemorrhage (eg, intracranial, pulmonary or intestinal tract haemorrhage), (3) extended hospitalisation due to haemorrhage, and (4) permanent disability and dysfunction due to haemorrhage. These events were assessed by the institutional ethics committee as well as external experts.

End points

The primary outcomes were the 28-day and 90-day survival rates. The secondary outcomes included 72 hours survival rates; number of days until DIC resolution;9 changes in SOFA scores, platelet counts, d-dimer values and CRP levels; blood and blood derivative administration amounts during the first 72 hours after diagnosis; and number of mechanical ventilation-free days.

Data analysis

An intent-to-treat analysis was used according to initial group assignment. When the basic assumptions of Student's t-test were not satisfied, a logarithmic transformation of the variables or the Mann-Whitney test was performed. For repeated comparisons, Bonferroni's correction was used. As our longitudinal data have comparisons with six hypotheses between the two groups, p<0.01 (0.05/6) was considered statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used for outcome analysis, in which 72-hour, 28-day or 90-day survival was set as the event occurrence. The log-rank test was used to compare the two groups. All p values were two-sided, and p<0.05 or p<0.01 was considered statistically significant.

All statistical analyses were performed with EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan),12 which is a graphical user interface for R V.3.1.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). More precisely, it is a modified version of R commander designed to add statistical functions frequently used in biostatistics.

Results

Study duration and enrolled patients

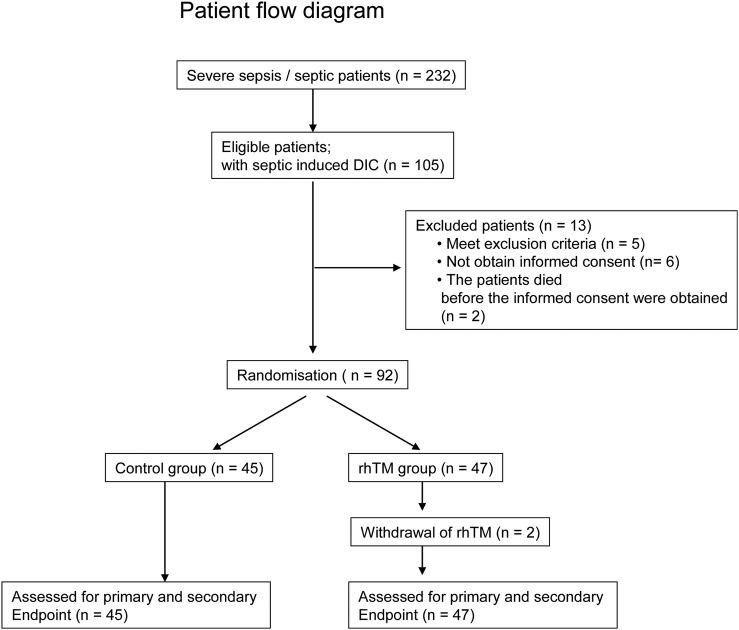

In total, 74 patients were enrolled through July 2014, which was less than planned. An extension of the patient enrolment period until February 2015 was approved by the institutional ethics committee. During the study period, 232 patients with severe sepsis were admitted to the hospital and provisionally enrolled in this study. Although 105 patients developed DIC within 24 hours after admission, 5 patients were excluded according to the exclusion criteria. Informed consent could not be obtained from eight other patients, including two patients who died. The two patients were solitary individuals, and we could not contact their legal representatives within 24 hours after admission. Thus, 92 patients were included in this study (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram. DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; rhTM, recombinant human thrombomodulin.

Baseline variables

Table 2 shows the patient baseline variables. The control and rhTM groups included 45 and 47 patients, respectively. The mean patient ages in the two groups were 77.2 and 74.7 years, respectively. Almost all patients were elderly. Approximately 65% of patients were men. The mean APACHE II score in the control group was 19.7 points, compared with 17.8 points in the rhTM group. The mean soluble serum TM values were 6.3 ng/mL in the control group and 8.0 ng/mL in the rhTM group. The mean PCT levels were 36.8 ng/mL in the control group and 39.3 ng/mL in the rhTM group.

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | Control (n=45) | rhTM* (n=47) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 77.2 (73.6 to 80.7) | 74.7 (70.6 to 78.8) |

| Male, n (%) | 28 (62.2%) | 32 (68.1%) |

| APACHE II | 19.7 (18.0 to 21.5) | 17.8 (16.2 to 19.4) |

| Soluble TM (M: 2.1–4.1 ng/mL, F: 1.8–3.9 ng/mL) | 6.3 (5.5 to 7.0) | 8.0 (5.7 to 10.2) |

| PCT (<0.5 ng/mL) | 36.8 (17.6 to 56.1) | 39.3 (19.0 to 59.7) |

*rhTM, recombinant human thrombomodulin. The rhTM values were measured before the infusion of rhTM. The continuous variables were the mean (95% CI).

F, female; M, male; TM, thrombomodulin; PCT, procalcitonin.

Follow-up variables

Table 3 shows the patient follow-up variables. More patients developed sepsis-induced hypotension and received vasopressors in the control group than in the rhTM group. Bacteraemia was diagnosed in ∼50% patients. The frequency of bacteraemia was slightly higher in the rhTM group. The most frequent infection site was the lungs, comprising ∼40% of infections, followed by the urinary tract/kidneys, gastrointestinal tract and skin/tissue. Approximately 64% of the responsible organisms were Gram-negative bacilli in the control and rhTM groups, and 36% were Gram-positive cocci. The most frequently used antibiotic was carbapenem. Renal replacement therapy was initiated in six and five patients in the control and rhTM groups, respectively. Mechanical ventilation was used in 26 patients in the control group and 21 in the rhTM group. Approximately 50% patients required mechanical ventilation. The median (25th, 75th centile) of rhTM administration duration was 2 days (1, 5 days).

Table 3.

Follow-up variables

| Characteristics | Control (n=45) | rhTM* (n=47) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis-induced hypotension,† n (%) | 26 (57.8) | 17 (36.1) | 0.42 (0.96 to 6.09) | 0.059* |

| Vasopressor, n (%) | 27 (60.0) | 16 (34.0) | 0.35 (0.13 to 0.87) | 0.021* |

| Norepinephrine, n (%) | 23 (51.1) | 13 (28.9) | ||

| Dopamine, n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| Dobutamine, n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| Epinephrine, n (%) | 2 (4.45) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| Bacteraemia (blood culture positive) | 22 (48.9) | 29 (61.7) | 1.67 (0.68 to 4.19) | 0.294* |

| Site of infection, n (%) | 0.795‡ | |||

| Lung | 17 (37.8) | 19 (40.4) | ||

| Urinary tract/kidney | 18 (40.0) | 13 (27.7) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 8 (8.8) | 5 (10.6) | ||

| Skin/soft tissue | 3 (6.7) | 4 (8.5) | ||

| Others | 2 (44.4) | 3 (6.4) | ||

| Responsible organism | ||||

| Gram-negative rod | 27 (60.0) | 32 (68.0) | 1.42 (0.56 to 3.66) | 0.515* |

| Gram-positive coccus | 18 (40.0) | 15 (31.9) | ||

| Antibiotic | ||||

| Carbapenem | 26 (57.8) | 31 (66.0) | 0.530‡ | |

| Cephalosporin | 18 (40.0) | 14 (29.8) | ||

| Other | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.3) | ||

| Renal replacement therapy, n | 6 (13.3) | 5 (10.6) | 0.78 (0.17 to 3.33) | 0.756* |

| Duration, day | 9.0 (8.3, 13.5)§ | 3.0 (2.0, 6.0)§ | NA | 0.099¶ |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 26 (57.8) | 21 (44.7) | 0.59 (0.24 to 1.46) | 0.220* |

*Fisher's exact test was performed.

†Sepsis-induced hypotension was defined as follows; despite adequate fluid resuscitation, vasopressors required to maintain mean arterial pressure ≥65 mm Hg.

‡χ2 Test was performed.

§The data were shown median and 25th and 75th centiles (25, 75 perventile).

¶Mann-Whitney test was performed.

NA, none available; rhTM, recombinant human thrombomodulin.

Outcome

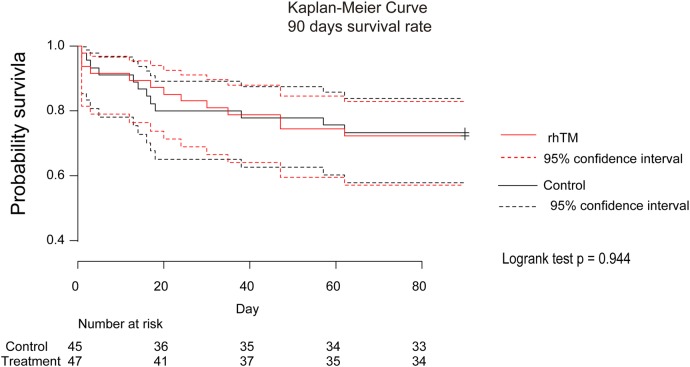

The 72 hours survival rates were 93% and 91% (Fisher's exact test, p=0.742) and 28-day survival rates were 84% and 83% (Fisher's exact test, p=0.717) in the control and rhTM groups, respectively. Online supplementary table S2 shows the results of Kaplan-Meier analysis, and figure 2 shows Kaplan-Meier curves for 90-day survival, illustrating survival rates of 73% and 72% in the control and rhTM groups, respectively (log-rank test, p=0.994).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of 90 days survival rate. The log-rank test showed that p=0.944. rhTM, recombinant human thrombomodulin.

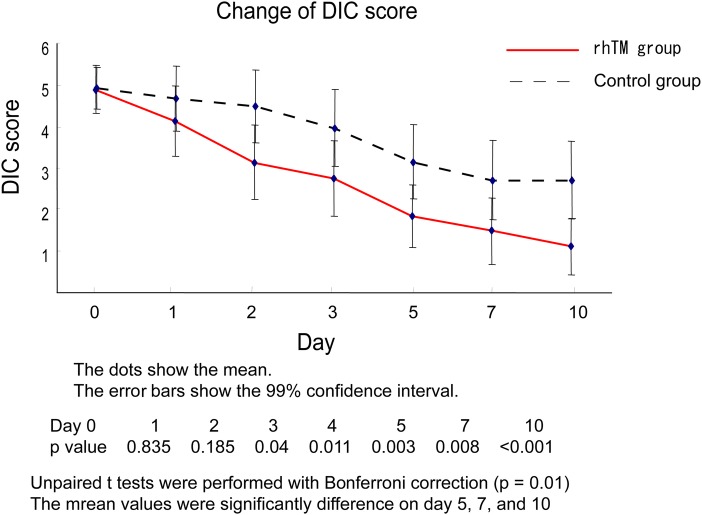

DIC resolution

The number of patients in whom DIC was resolved within 72 hours in the rhTM and control groups were 56% (27/48) and 40% (17/42), respectively (OR=2.45, 95% CI 0.95 to 6.52, p=0.0516, Fisher's exact test). The number of patients in whom DIC resolved within 7 days in the rhTM and control groups were 91% (39/43) and 61% (27/41), respectively (OR=4.96, 95% CI 1.36 to 22.97, p=0.0075, Fisher's exact test). Figure 3 shows the changes in the DIC score through 10 days. The mean DIC score was significantly lower in the rhTM group, beginning on day 5 (p<0.01).

Figure 3.

Change of DIC score. Unpaired t-test with Bonferroni correction was performed in the rhTM group versus control group at days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 and 10. The p<0.001 (0.05/6) was considered statistically significant. DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; rhTM, recombinant human thrombomodulin.

Coagulation data

Online supplementary table S3 shows data for d-dimer, platelet, PTINR, fibrinogen and ATIII. The relative changes from baseline in the levels of d-dimer were significantly lower in the rhTM group than in the control group, on days 3 and 5. The relative changes from baseline for platelet counts, PTINR, fibrinogen and ATIII were not different between the groups at any time point.

Inflammation data

WCC and CRP counts were not different between the groups at any time point (see online supplementary table S3).

SOFA scores

The relative changes from baseline for respiratory SOFA scores and total SOFA scores were not significantly different between the groups at any time point (see online supplementary table S4).

Ventilator-free days, blood transfusion amounts, and albumin and heparin use

The mean number of ventilator-free days in the rhTM and control groups were 15.5 (10.7 to 20.2) and 17.5 days (9.2 to 17.7), respectively (see online supplementary table S5). The difference of 2.0 days (−4.4 to 8.4) between the groups was not significant (p=0.530). The transfusion amounts of RBCs, FFP and platelets were not different between the groups. Four patients (8.5%, 4/47) were administered albumin in the rhTM group compared with 16 patients (35.6%, 16/45) in the control group. Seven patients with deep venous thrombosis in the control group and one in the rhTM group were treated with unfractionated heparin.

Other laboratory findings

Online supplementary table S6 shows albumin, ALP, ALT, AST, LDH, total bilirubin, BUN, creatinine, Na, Cl, RBC and haemoglobin data for both groups at days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 and 10. Although serum albumin values were significantly higher in the rhTM group only on day 1, the relative change from baseline was not significantly different between the groups. Other laboratory data were not significantly different between the groups.

Adverse events

One patient in the control group and two in the rhTM group experienced adverse events that required either treatment alterations or additional therapies. The patient in the control group developed melena caused by large intestinal diverticulitis and underwent transcatheter arterial embolisation. One patient in the rhTM group developed bleeding from an ulcer at the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb (Foster Ib) and received RBC transfusion and endoscopic haemostasis (clipping). Another patient in this group was diagnosed with meningitis and severe sepsis with DIC and was treated with rhTM. Brain CT on day 2 revealed a large cerebral infarction, and rhTM administration was discontinued. On day 3, the patient exhibited disturbances in consciousness; brain CT was repeated, revealing a haemorrhagic brain infarction. Following a review, the ethics committee concluded that the causal relationship between haemorrhagic complications and rhTM administration was unclear.

Post hoc analysis

Survival rate

We selected the patients with mechanical ventilation from the study population and performed a survival analysis at 28 and 90 days for the rhTM and control groups. The 28-day survival rates in the treatment and control groups were 71% (15/21) and 69% (18/26; OR=1.1, 95% CI 0.27 to 4.8, p=1.0, Fisher's exact test), respectively. The 90-day survival rates in the treatment and control groups were 62% (13/21) and 62% (16/26; OR=1.0, 95% CI 0.27 to 3.9, p=1, Fisher's exact test), respectively.

APACHE II scores were ≥20 (severe) or <20 (moderate status; online supplementary table S7). The moderate and severe groups included 51 and 41 patients, respectively. In the severe group, 90-day survival rates were 52% and 60% in the control and rhTM groups, respectively (log-rank test p=0.524), with similar findings recorded in the moderate group.

DIC resolution

The 28-day mortality rate among patients in whom DIC was resolved within 7 days was 2.6% (1/39) in the rhTM group compared with 50.0% (4/8) among those in whom DIC was not resolved (OR=0.03, 95% CI 0.0 to 0.4, p=0.0018, Fisher's exact test). In the control group, the 28-day mortality rate among patients in whom DIC was resolved within 7 days was 0% (0/27); conversely, the rate for those in whom DIC was not resolved was 50% (9/18; OR=0, 95% CI 0.0 to 0.2, p<0.001, Fisher's exact test). The mortality rate was significantly lower among patients in whom DIC was resolved.

However, differences in the 28-day and 90-day survival rates were not observed between the control and rhTM groups among patients who experienced DIC resolution within 3 or 7 days of admission (see online supplementary table S8). Differences in the 28-day and 90-day survival rates were not observed between patients who experienced DIC resolution within 3 days in the rhTM group and those who experienced resolution within 7 days in the control group. Online supplementary figure S1 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve.

bmjopen-2016-012850supp_figure.pdf (43.9KB, pdf)

Discussion

Our single-centre, open-label RCT found that rhTM treatment did not increase 72-hour, 28-day or 90-day survival rates among patients with severe septic -induced DIC. The results were different from a series of reports describing the effectiveness of rhTM.5–7 13 According to our findings, a sample size of ∼23 000 would be required to demonstrate a significant difference between the rhTM and control groups within our observation period.

Through 2015, five retrospective studies reported the efficacy of rhTM in patients with sepsis and DIC.5–7 13 14 These studies reported mortality rates of 8.3–40% in the rhTM group and 33–57% in the control group. These mortality rates were higher than our values. This may be explained by differences in disease severity. In four of the studies, patients with sepsis who required mechanical ventilation were included.5–7 14 In contrast, one phase IIb study8 and another retrospective subanalysis15 of a phase III clinical trial3 reported mortality rates of 17.8% in the rhTM group and 21.4% in the control group, respectively, and 21.6% in the rhTM group and 31.6% in the control group, respectively. The former study diagnosed DIC according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) criteria, and the latter study diagnosed DIC according to the JAAM DIC criteria. As we also administered rhTM to patients with sepsis according to the JAAM DIC criteria, our mortality rates may be lower than those of the retrospective studies. However, our mortality rates were similar to those of the two prospective studies. We believe that our results provide real-world evidence of the efficacy of rhTM in Japan.

rhTM treatment significantly decreased DIC scores compared with the control group, indicating that the drug facilitated DIC resolution. Compared with the control group, rhTM treatment significantly lowered d-dimer levels on days 3 and 5. The results almost matched those of two RCTs.3 8 However, platelet counts and prothrombin times were not different between the groups. Thus, decreases in FDP values may induce declines in the DIC score (the changes in the FDP values are shown in online supplementary table S2).

Aikawa et al15 stated that “the 28-day mortality rate among patients in whom the DIC resolved was 3.7% (1/27) in rhTM group, the rate for those in whom the DIC did not resolve was 46.2% (6/13) (p=0.0026, Fisher's exact test). In the heparin treatment group, the 28-day mortality rate among patients in whom the DIC resolved was 15% (3/20); the rate for those in whom the DIC did not resolve was 43.8% (7/16) (p=0.0732, Fisher's exact test).” They reported that “the 28-day mortality rates were significantly lower for patients in whom the JAAM DIC was resolved within 7 days than in those in whom the JAAM DIC was not resolved.” Our results were similar to theirs.

We examined patients who experienced DIC resolution within 3 or 7 days, but no difference in survival rates was recorded between the rhTM and control groups. Moreover, survival rates were not different between patients in the rhTM group who experienced DIC resolution within 3 days and those in the control group who experienced DIC resolution within 7 days. These results illustrated that the 28-day mortality rates were lower for patients in whom JAAM DIC was resolved within 7 days, but the outcome did not change after the use of rhTM if patients recovered from DIC within 7 days.

There were no differences in SOFA scores, number of ventilator-free days and volume of blood transfusion between the rhTM and control groups. Conversely, albumin and heparin use were lower in the rhTM group, although the small number of patients precludes any definitive conclusions. A decline in the DIC score by the rhTM use may not improve the outcome of patients with severe septic-induced DIC compared with the control group. Our study did not uncover sufficient evidence of the effects of treatment with rhTM for sepsis-induced DIC on patient outcome. However, rhTM use has been drastically increasing in Japan despite a lack of clear evidence of its effectiveness.16

Our results unfortunately could not find an effectiveness of rhTM. Yet, we believe that the ongoing phase III study (Clinical trials. gov identifier. NCT01598831) could reveal whether our results would be closer to the truth or our study method is inappropriate.

Study limitations

As this study was the open-label RCT, this may have differences in the behaviour of patients and/or study staff. In addition, it requires caution and prudence for interpretation of our results due to a single-centre study. Our entry criteria targeted those patients diagnosed as DIC in accordance with the JAAM DIC criteria. For the ongoing phase III study performed in Europe/the USA, the entry criteria are set for patients with cardiovascular dysfunction or respiratory failure and severe sepsis with PTINR>1.40. Therefore, it is more severe than our entry criteria. Our study might show a difference in disease severity as compared to other studies. The number of patients calculated before the study might not possibly be appropriate. The ongoing phase III study planned that the estimated enrolment was 800 patients. The small number of patients in our study may have caused no significant result.

Conclusion

rhTM treatment decreased d-dimer values in patients with severe septic-induced DIC but did not increase survival rates. We do not recommend the routine use of rhTM in these patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Sasaki, Dr Kobayashi, Dr Inaka, Dr Inagaki, Dr Oda, Dr Kiriyama, Dr Nakao, Dr Ikeda, Dr Shigeta, Dr Tachino, Dr Nagashima, Dr Makinouchi, Dr Hiruma and Dr Kobayakawa for their critical contribution to this study.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Dr Ryou Sasaki, Dr Kentarou Kobayashi, Dr Aki Inaka, Dr Takashi Inagaki, Dr Hiroko Oda, Dr Yuko Kiriyama, Dr Shunichirou Nakao, Dr Keiko Ikeda, Dr Kenta Shigeta, Dr Joutarou Tachino, Dr Ayaka Nagashima, Dr Ryuichirou Makinouchi, Dr Hiromitu Hiruma and Dr Masao Kobayakawa.

Contributors: MW, TU and AH performed the acquisition of the data. TU, AH and NT revised the manuscript and approved the final version. AK and AH contributed to the conception of the work and approved the final version. NT and AH performed the statistical analysis. In addition, all authors had agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Research from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (26A201).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: NCGM-G-001163-00.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.2n6v4.

References

- 1.Esmon CT. The interactions between inflammation and coagulation. Br J Haematol 2005;131:417–30. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abeyama K, Stern DM, Ito Y et al. The N-terminal domain of thrombomodulin sequesters high-mobility group-B1 protein, a novel antiinflammatory mechanism. J Clin Invest 2005;115:1267–74. 10.1172/JCI22782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito H, Maruyama I, Shimazaki S et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin (ART-123) in disseminated intravascular coagulation: results of a phase III, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J Thromb Haemost 2007;5:31–41. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02267.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levi M, Toh CH, Thachil J et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol 2009;145:24–33. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07600.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamakawa K, Fujimi S, Mohri T et al. Treatment effects of recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin in patients with severe sepsis: a historical control study. Crit Care 2011;15:R123 10.1186/cc10228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa Y, Yamakawa K, Ogura H et al. Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin improves mortality and respiratory dysfunction in patients with severe sepsis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;72:1150–7. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182516ab5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamakawa K, Ogura H, Fujimi S et al. Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin in sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: a multicenter propensity score analysis. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:644–52. 10.1007/s00134-013-2822-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent JL, Ramesh MK, Ernest D et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin, ART-123, in patients with sepsis and suspected disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med 2013;41:2069–79. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828e9b03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gando S, Iba T, Eguchi Y et al. A multicenter, prospective validation of disseminated intravascular coagulation diagnostic criteria for critically ill patients: comparing current criteria. Crit Care Med 2006;34:625–31. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000202209.42491.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 2008;36:296–327. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacIntyre NR, Cook DJ, Ely EW Jr et al. Evidence-based guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support: a collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians; the American Association for Respiratory Care; and the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 2001;120(6 Suppl):375S–95S. 10.1378/chest.120.6_suppl.375S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013;48:452–8. 10.1038/bmt.2012.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato T, Sakai T, Kato M et al. Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin administration improves sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation and mortality: a retrospective cohort study. Thromb J 2013;11:3 10.1186/1477-9560-11-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshimura J, Yamakawa K, Ogura H et al. Benefit profile of recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin in sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: a multicenter propensity score analysis. Crit Care 2015;19:78 10.1186/s13054-015-0810-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aikawa N, Shimazaki S, Yamamoto Y et al. Thrombomodulin alfa in the treatment of infectious patients complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation: subanalysis from the phase 3 trial. Shock 2011;35:349–54. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318204c019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murata A, Okamoto K, Mayumi T et al. Recent change in treatment of disseminated intravascular coagulation in Japan: an epidemiological study based on a national administrative database. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016;22:21–7. 10.1177/1076029615575072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012850supp_table.pdf (184.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012850supp_figure.pdf (43.9KB, pdf)