Abstract

Objective

To examine the effect of the first introduction of measles vaccine (MV) in Guinea-Bissau in 1979.

Setting

Urban community study of the anthropometric status of all children under 6 years of age.

Participants

The study cohort included 1451 children in December 1978; 82% took part in the anthropometric survey. The cohort was followed for 2 years.

Intervention

In December 1979, the children were re-examined anthropometrically. The participating children, aged 6 months to 6 years, were offered MV if they did not have a history of measles infection. There were no routine vaccinations in 1979–1980.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Age-adjusted mortality rate ratios (MRRs) for measles vaccinated and not vaccinated children; changes in nutritional status.

Results

The nutritional status deteriorated significantly from 1978 to 1979. Nonetheless, children who received MV at the December 1979 examination had significantly lower mortality in the following year (1980) compared with the children who had been present in the December 1978 examination but were not measles vaccinated. Among children still living in the community in December 1979, measles-vaccinated children aged 6–71 months had a mortality rate of 18/1000 person-years during the following year compared with 51/1000 person-years for absent children who were not measles vaccinated (MRR=0.30 (0.12–0.73)). The effect of MV was not explained by prevention of measles infection as the unvaccinated children did not die of measles infection.

Conclusions

MV may have beneficial non-specific effects on child survival not related to the prevention of measles infection.

Keywords: child mortality, eradication, measles vaccine, non-specific effects of vaccines

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There are few studies of what happened when the measles vaccine was introduced in low income countries. Since 1978, we have followed an urban community in Bissau, the capital of Guinea-Bissau, with anthropometric surveys.

More than 80% of children <6 years of age participated in the nutritional surveys and the measles vaccination campaign.

When the measles vaccine was introduced in 1979, mortality declined threefold from 1 year to the next. The difference was not explained by changes in nutritional status.

Although this is not a randomised study, it suggests strong beneficial non-specific effects of measles vaccine. Since measles is soon to be eradicated, it is well to remember that MV has beneficial non-specific effects on child survival.

Introduction

The general childhood immunisation programme became widespread in Africa only after UNICEF's Universal Childhood Immunization programme in the mid-1980s. At the time the recommended schedule was BCG and oral polio vaccine (OPV) at birth, diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis (DTP) and OPV in three doses with an interval of 4 weeks, starting at 2 or 3 months of age, plus measles vaccine (MV) at 9 months and booster doses of DTP and OPV in the second year of life. There are surprisingly few studies of what the introduction of different vaccines meant for overall child survival.1

At the Bandim Health Project (BHP), we have followed a small urban community, Bandim, in the capital of Guinea-Bissau since 1978 and we took part in the sequential introduction of the different vaccines before a full-fledged national programme was implemented in 1986 with UNICEF support. We followed the community with a demographic surveillance system from December 1978.

MV was offered to all children aged 6 months to 6 years of age at the first general vaccination campaign in December 1979.2 We therefore compared mortality in the prevaccination year with the year following the introduction of MV. There were no computers in Bissau at the time and we have previously only been able to provide an assessment of MV for children aged 6–36 months based on tallying the number of children under observations, the number of vaccinations and the number of deaths. The tallying methods provided limited possibilities for examining and controlling for the impact of age, nutritional status and other factors.2 Hence, to better assess the effect of MV, we have now digitalised the original data and reanalysed the data using more advanced statistical methods. Whereas the data previously have mainly been described in terms of the change in mortality rates in the community before and after the introduction of MV, we have now also compared the mortality of children who were eligible for MV and did or did not receive MV.

Methods

Background

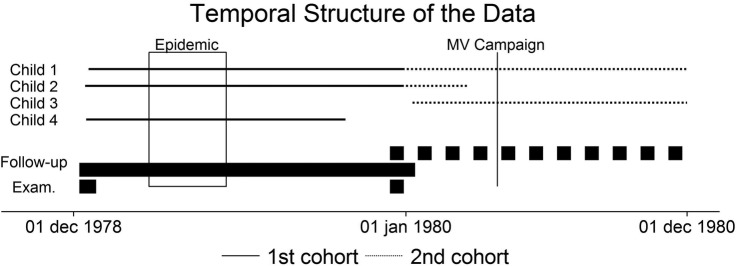

In the fall of 1978, a ‘de jure’ census was completed in the study area Bandim. After numbering the houses on a map, each household was visited and all the individuals living there were recorded with name, age and relation to the household head. An ongoing registration of births and deaths was set up employing local community activists who were trained and supervised by us. In December 1978, we conducted an anthropometric examination of all children <6 years of age to be able to assess malnutrition in this community3 (figure 1). Bandim had eight subdistricts and the inline examinations were conducted over 1–2 days in each of these subdistricts. Children absent on these days—usually because they were travelling—were not examined.

Figure 1.

The duration of phases (first examination, second examination and follow-up periods) is shown with thick lines. Four examples of follow-up periods are shown with thin lines. Follow-up starts on a scheduled examination date; the first and the second follow-up periods do not overlap for a specific individual. MV, measles vaccine.

In early 1979, the area experienced a severe measles epidemic.3 4 At the re-examination in December 1979, the children who were present and older than 6 months were offered MV (Attenuvax, Merck-Sharp & Dome). However, two groups were not offered MV: first, children whose mother or guardian declared that the child had had measles in the 1979 epidemic or earlier; and second, children whose mother or guardian declared that the child had been vaccinated at the time of the epidemic. This latter group is called ‘suspected MV’ in the present analysis. When we conducted the re-examination, we believed that the children had received MV at the child clinic in town.

The measles vaccinations we administered were recorded on the child's growth card. Our team did not register who received MV, but we know from later inspection of these cards that children who were present, had not had measles infection, had not had ‘suspected MV’ and were at least 6 months old did receive MV.2

There was no community vaccination programme at the time in Guinea-Bissau. As shown below, the children who had ‘suspected MV’ had either received no MV or an MV which was no longer effective. Hence, the children not attending the examination in December 1979 had not received an effective vaccine and we considered these children MV unvaccinated in the present analyses. The children not attending the 1979 examination could be different from the ones who were attending. We have therefore used data from the 1978 examination to test whether mortality was likely to differ for children attending and not attending the examinations.

Follow-up

The sequence of events has been depicted in figure 1. A new census was conducted in the area in December 1981 to January 1982. Hence, through the demographic surveillance system, survival information was available for all children registered in the fall of 1978 and in December 1979. We followed the first cohort from the date of the scheduled 1978 examination until the date of the scheduled 1979 examination or until death or until the date of moving away from the study area, whichever came first. For the second period, follow-up started at the scheduled 1979 examination and ended on 1 December 1980, or at death or on the date of moving away (figure 1). A new round of measles vaccinations started in December 1980, and we therefore decided to end follow-up before the unvaccinated children were likely to receive vaccination.

Data control

The data from the two examinations in December 1978 and December 1979 were linked to the population register to facilitate long-term follow-up. Using the original examination forms, key variables for the survival analysis including date of birth, sex and examination dates were checked for consistency. The consistency and inconsistencies in relation to the previous analysis2 have been described in the online supplementary material.

bmjopen-2016-011317supp.pdf (51.7KB, pdf)

Analysis and statistical method

The children with a weight or length recorded in the 1978 examination or the 1979 examination, respectively, have been considered ‘examined’ in the respective year and the other children registered but without a weight or height measured have been considered ‘absent’. Furthermore, the children examined in the 1979 examination were classified as ‘measles vaccinated′’, ‘suspected MV’ and ‘previous measles infection’ according to the information provided during the examination.

The mortality of different groups has been compared using age-specific mortality rate ratios (MRRs) with age being age at start of a follow-up period. The reported CIs are exact. In this way, we have estimated age-specific and age-adjusted MRRs for several factors, including sex, examination status and vaccination status. To examine whether there were major differences between children being present and absent from the examination in December 1979, we used the anthropometric information from children who had taken part in the 1978 examination. The WHO z-scores for child growth were used to compare weight and height of children who participated or who were absent in the 1979 examination.5 We also compared the nutritional status of the 1978 and the 1979 cohorts.

Background factors such as household type (polygamy/monogamy; sex of household head), number of generations in the household and ethnicity were available in the data and could be used for example, in a Poisson regression. However, owing to the limited number of events, we have not adjusted for these variables in our survival analyses as such adjustment would entail a substantial risk of overfitting the model.

Ethics

The study of nutritional status was planned between the SAREC (Swedish Agency for Research Collaboration with Developing Countries) and the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Guinea-Bissau. At the time, there was no national committee for research ethics. Interviews and anthropometric examinations were explained to the parents in terms of the MOH needing to know why mortality was so high. Participation was assumed to reflect parental consent.

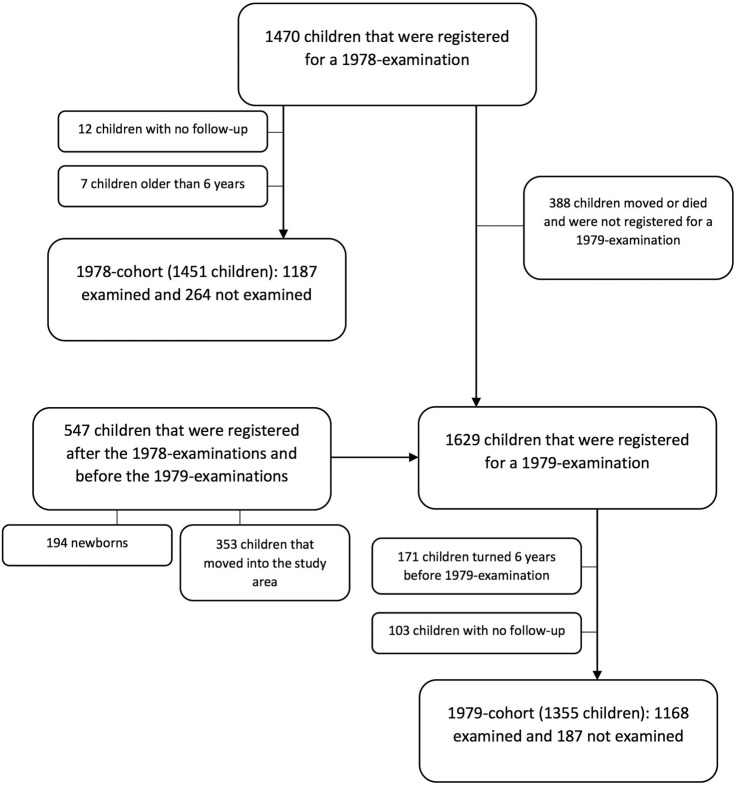

Results

In December 1978, 6217 individuals were registered in the census in Bandim; 1451 were <6 years of age and were invited to take part in the 1978 examination and 82% (1187/1451) participated (figure 2). In December 1979, 86% of children <6 years of age (1168/1355) took part in the 1979 examination (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of children taking part in the 1978 and 1979 cohorts.

As seen in table 1, mortality rates were very high during the first year of the study (table 1A). Mortality declined markedly in the second year of the study (table 1B). The age-adjusted MRR for the second year compared with the first year was 0.30 (0.21 to 0.45).

Table 1.

Mortality rates per 100 person-years (deaths/person-years) overall and by sex in Bandim, Guinea-Bissau. Children aged 0–5 years

| Age in months | All | Females | Males | Mortality rate ratio in females vs males (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) From 1978 examination, 1 year of follow-up | ||||

| 0–5 | 14.9 (24/160.5) | 14.3 (12/83.9) | 15.7 (12/76.7) | 0.91 (0.38 to 2.22) |

| 6–11 | 18.8 (23/122.2) | 20.1 (13/64.6) | 17.4 (10/57.6) | 1.16 (0.47 to 2.95) |

| 12–35 | 12.5 (57/456.2) | 10.7 (25/232.7) | 14.3 (32/223.5) | 0.75 (0.43 to 1.31) |

| 36–71 | 2.9 (16/560.3) | 2.4 (7/297.1) | 3.4 (9/263.2) | 0.69 (0.22 to 2.08) |

| Total* | 9.3 (120/1299.2) | 8.5 (57/678.3) | 10.1 (63/620.9) | 0.84 (0.59 to 1.20) |

| (B) From 1979 examination, 1 year of follow-up | ||||

| 0–5 | 3.8 (5/131.5) | 5.6 (4/71.7) | 1.7 (1/59.8) | 3.34 (0.33 to 164.3) |

| 6–11 | 5.8 (8/138.4) | 3.4 (2/58.5) | 7.5 (6/79.9) | 0.46 (0.04 to 2.55) |

| 12–35 | 4.3 (18/415.4) | 4.3 (9/209.2) | 4.4 (9/206.2) | 0.99 (0.35 to 2.80) |

| 36–71 | 0.6 (3/489.5) | 0.4 (1/254.3) | 0.9 (2/235.2) | 0.46 (0.01 to 8.88) |

| Total* | 2.8 (34/1174.8) | 2.7 (16/593.7) | 3.1 (18/581.1) | 0.92 (0.46 to 1.82) |

*Age-adjusted.

Clinical examination and simple treatment was offered in connection with the anthropometric examinations in December 1978, but mortality during the subsequent year was not lower for the children who attended than for those who were absent, the MRR being 1.35 (0.80 to 2.28) (table 2). In stark contrast, in the second year, the MRR was 0.49 (0.22 to 1.09) for those who were clinically examined compared with those who were absent in December 1979 (table 2).

Table 2.

Mortality rates per 100 person-years (deaths/person-years) according to presence at 1978 and 1979 examinations

| Mortality rate (deaths/person-years) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in months | Examined | Absent | Mortality rate ratio, examined vs absent (95% CI) |

| 1978 examination | |||

| 0–5 | 15.7 (18/114.9) | 13.1 (6/45.7) | 1.19 (0.45 to 3.67) |

| 6–11 | 18.2 (18/98.9) | 21.5 (5/23.3) | 0.85 (0.30 to 2.92) |

| 12–35 | 13.0 (51/391.8) | 9.3 (6/64.4) | 1.40 (0.60 to 3.98) |

| 36–71 | 3.4 (16/472.4) | 0 (0/87.9) | NA |

| Total* | 9.9 (103/1077.9) | 7.2 (17/221.3) | 1.35 (0.80 to 2.28) |

| 1979 examination | |||

| 0–5 | 4.5 (5/111.1) | 0 (0/20.4) | NA |

| 6–11 | 3.4 (4/118.2) | 19.8 (4/20.2) | 0.17 (0.03 to 0.92) |

| 12–35 | 3.8 (14/365.6) | 8.0 (4/49.8) | 0.48 (0.15 to 1.99) |

| 36–71 | 0.7 (3/427.6) | 0 (0/61.9) | NA |

| Total* | 2.6 (26/1022.5) | 5.2 (8/152.3) | 0.49 (0.22 to 1.09) |

Children aged 0–5 years.

*Age-adjusted.

NA, not applicable.

The following analysis is restricted to the age group 6–71 months because these children were eligible to receive MV. The mortality rate of ‘absent’ children was similar in the first and the second years of the study, the MRR being 0.89 (0.36 to 2.22) (table 2). Hence, the decline in mortality between 1979 and 1980 occurred among children who were present at the nutritional examinations. We compared the nutritional status in December 1978 and in December 1979 by calculating the age-specific z-score means and furthermore using a mixed effects models with a random intercept on child to estimate z-score differences between years (table 3). Age and year were included in the mixed effects model as predictors. All three z-scores were significantly lower in 1979 than in 1978 (p<0.001). Hence, the better survival during the second year (1980) was not explained by improved nutritional status. Using a linear normal model, there was no significant difference in 1978 between those who were examined and those who were absent in December 1979, the mean differences in z-scores for weight-for-age, height-for-age and weight-for-height being 0.07, 0.09 and 0.06, respectively, and the p values being 0.51, 0.50 and 0.61.

Table 3.

Mean z-scores for children examined at age 0–4 years in 1978 and in 1979

| Weight-for-age z-score |

Length/height-for-age z-score |

Weight-for-length/height z-score* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in months | 1978 | 1979 | 1978 | 1979 | 1978 | 1979 |

| 0–5 | −0.50 [134] | −0.44 [126] | −0.61 [134] | −0.80 [122] | 0.02 [134] | 0.37 [121] |

| 6–11 | −0.60 [111] | −0.71 [134] | −0.63 [111] | −0.80 [133] | −0.28 [111] | −0.32 [133] |

| 12–36 | −0.85 [436] | −1.06 [426] | −1.37 [433] | −1.49 [425] | −0.18 [431] | −0.39 [425] |

| 36–60 | −0.81 [365] | −1.00 [341] | −1.41 [363] | −1.41 [340] | 0.04 [359] | −0.25 [339] |

| All ages | −0.76 (1.03) | −0.92 (1.03) | −1.21 (1.23) | −1.29 (1.22) | −0.09 (1.03) | −0.24 (1.06) |

| z-score difference† | −0.19 (−0.25, −0.14) | −0.14 (−0.20, −0.07) | −0.16 (−0.23, −0.10) | |||

[ ] is the number of children with a specific z-score in the age group; () is the SD for the z-scores.

*The WHO z-scores are based on measuring length for children under 2 years of age and height for children aged 2 years and older.

†From a random intercept model.

Apart from a clinical examination by a paediatrician which took place at both examinations, measles vaccination was the only intervention offered to children in the 1979 examination. Compared with the children who were present in December 1978 (did not receive MV), the MRR for children aged 6–71 months who received MV in December 1979 was 0.19 (0.10–0.36).

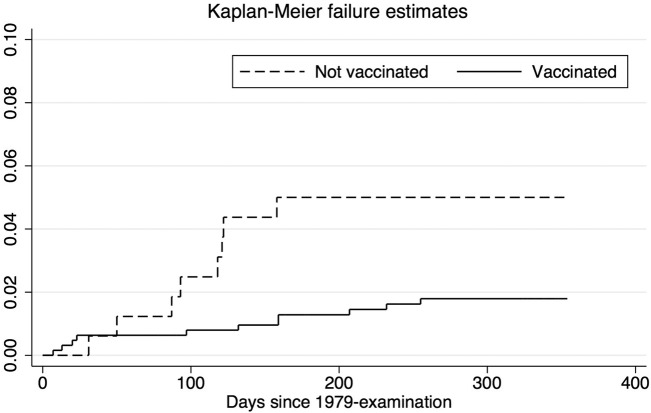

There was also a marked difference in mortality for children who received MV compared with absent children who did not receive MV in December 1979 (MRR=0.30 (0.12 to 0.73)) (table 4, figure 3). None of the deaths among absent children in the second year were due to measles infection. A small MV campaign was organised on 17 April 1980 for children <6 months of age in December 1979 and a few of the children absent in December 1979 may also have received MV in the April 1980 campaign. When we compared measles-vaccinated and absent children only between December 1979 and 17 April 1980, the MRR was 0.17 (0.06 to 0.52) (see online supplementary table 1).

Table 4.

December 1979–1980 mortality rates per 100 person-years (deaths/person-years) according to vaccination status

| Mortality rate (deaths/person-years) |

Mortality rate ratios MV vaccinated/absent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in months | Examined (MV vaccinated) | Examined (previous measles) | Examined (suspected MV) | Absent | |

| 6–11 | 3.7 (4/108.8) | 0 (0/2.8) | 0 (0/6.6) | 19.8 (4/20.2) | 0.19 (0.03–1.00) |

| 12–35 | 1.7 (4/238.7) | 5.0 (4/80.7) | 13.0 (6/46.2) | 8.0 (4/49.8) | 0.21 (0.04–1.12) |

| 36–71 | 1.4 (3/208.3) | 0 (0/137.7) | 0 (0/81.7) | 0 (0/61.9) | NA |

| Total* | 1.8 (11/555.8) | 1.9 (4/221.1) | 4.9 (6/134.5) | 5.1 (8/131.8) | 0.30 (0.12–0.73) |

Children aged 6–71 months (eligible for vaccination).

Children who were examined but reported previous measles infection or measles vaccination did not receive MV. Absent children did not receive MV.

*Age-adjusted.

MV, measles vaccine.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for children measles vaccinated or not vaccinated (absent) at the 1979 examination. Children with previous measles infection or suspected measles vaccination have not been presented.

The response to MV is believed to be suboptimal before maternal antibodies have disappeared completely after about 12 months of age.6 Hence, it is worth noting that the difference between MV vaccinated children and absent children was marked for children aged 6–11 months at the time of vaccination, the MRR being 0.18 (0.03 to 1.00) (table 4).

Interestingly, the group we assumed to have been measles vaccinated during the epidemic (‘suspected MV’) and who were therefore not vaccinated by us had a mortality rate similar to the rate of the absent children, the MRR being 1.07 (0.33 to 3.45). We may have misunderstood the information about being vaccinated as we did not explore which vaccine they received during the epidemic; two children in the ‘suspected MV’ group died of measles during 1980.2 Alternatively, the MV they received may have been ineffective because storage conditions were not optimal in the 1970s.

We have previously reported that children who survive measles infection may have lower mortality than children who have not had measles infection.7–10 It is therefore worth noting that the children whose mother declared in December 1979 that their child had already had measles infection tended to have lower mortality than absent children, the MRR being 0.52 (0.13 to 2.10).

Previous studies have suggested that MV has a stronger beneficial effect for females than for males.11–14 The present study was too small to address this issue with certainty (see online supplementary table 2).

Discussion

Main observations

The introduction of MV was linked to a major reduction in mortality compared with both the mortality rate in the previous year and the mortality rate of those who remained measles-unvaccinated. The study also showed that the beneficial effect of MV was seen for the youngest children vaccinated at 6–11 months of age.

Strengths and weaknesses

For those who were present and received MV in December 1979, mortality declined fivefold compared with the previous year. Bandim experienced a major measles epidemic causing more than 50% of the deaths between December 1978 and December 1979,2 so a large part of this reduction in mortality is explained by the absence of measles infection. Still, when we compared measles-vaccinated and measles-unvaccinated children in the subsequent year, there was a threefold difference in mortality. This difference was not explained by prevention of measles infection as there were no measles deaths in the absent group during follow-up.

The children who were not present at the 1979 examination and therefore did not receive MV could have been inherently weaker. However, there is little support for this possibility. In the first year, after the 1978 examination, absent or travelling children did not have higher mortality than those taking part in the examination. Furthermore, the children who were absent in December 1979 had essentially the same mortality rate as the children who were absent in December 1978 (table 2) and there had not previously been a difference in nutritional status for the children who were respectively examined or absent at the 1979 examination.

Consistency or contradiction with previous studies

There are only four other studies comparing community mortality before and after the introduction of MV, three from Africa and one from India. In all studies, the reduction in mortality was at least 50%, clearly consistent with this study from Guinea-Bissau11 12 15 16 and suggesting that MV may prevent more than just measles infection; it has beneficial non-specific effects.

There is by now a fairly large number of studies which have compared mortality of measles-vaccinated and measles-unvaccinated children either by vaccinating in some but not in other districts or by comparing vaccinated and unvaccinated children within the same community.6 13

This study suggested a threefold to fourfold lower mortality among the measles-vaccinated children compared with the measles-unvaccinated children. An effect of this magnitude in an observational study may appear ‘unbelievable’. Randomised trials were not conducted in high-mortality countries before the introduction of MV, so we do not know the ‘true’ effect of MV versus no MV. However, a few small trials tested the effect of MV versus no MV in connection with studies of the introduction of MV before 9 months of age. In a randomised trial in Sudan, mortality was 91% (29–99%) lower between 5 and 9 months of age for children who received a high-titre MV compared with control vaccine (meningococcal vaccine).17 In Guinea-Bissau, children who received MV at 4.5 months of age in a randomised trial, and had not received neonatal vitamin A supplementation, had 67% (14–87%) lower mortality than controls randomised to no vaccine at 4.5 months of age.17 Several natural experiment studies have also suggested very strong effects of MV on mortality.6

The WHO's Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on immunisation recently reviewed the potential non-specific effects of BCG, DTP and MV.13 The review found that BCG and MV almost halved mortality and this effect was unlikely to be fully explained by prevention of tuberculosis or measles. SAGE concluded that further studies on the non-specific effects of vaccines are warranted.18

The current policy for MV is based on the assumption that it would be better to vaccinate with MV after 12 months of age when maternal antibodies have disappeared and the children get a higher antibody response to MV.19 The only reason that MV is used at 9 months of age in low income countries is that if it was given at 12 months, too many children would catch measles before vaccination. Thus, the WHO recommends increasing the age of measles vaccination once measles infection is under control.20 However, it should be noted that all existing observations, including this study, contradict the current policy; in fact, all current studies suggest that the overall mortality effect of MV is better when given early.6 The reason is probably that the non-specific effects of MV are stronger when the vaccine is given early. We have recently reported that children who were measles vaccinated in the presence of a maternal antibody had much better survival than children measles vaccinated in the absence of a maternal antibody.21 This would explain why early vaccination is better because the earlier the vaccine is given, the more children will still have some maternal antibody.

Interpretation and implications

The idea that vaccines may have non-specific effects has been controversial and very few immunologists have examined potential mechanisms. However, the evidence is beginning to emerge. It has been shown that BCG induces epigenetic changes which reprogramme the innate immune system to stronger proinflammatory responses. Vaccines may also induce heterologous effects due to cross-reacting T-cell epitopes.22–24 MV may have such non-specific effects on the innate and adaptive immune system. We recently showed that MV versus no MV was associated with higher plasma MCP-1 levels. The effect was significant in its own right among females. Furthermore, MV had significantly positive effects on plasma interleukin (IL)-1Ra and IL-8 levels in females, but not in males.25

It has recently been suggested by a major paper in Science that the beneficial non-specific effects of MV are due to MV preventing the profound measles-induced immune amnesia, which is supposed to lead to excess mortality from other causes than measles infection.26 However, the problem with that hypothesis is that all available studies7–10—including the present one—suggest lower mortality rather than excess mortality among those who survive the acute phase of measles infection.

All vaccination policies regarding age of vaccination and number of doses are based entirely on assessment of the specific effects of the vaccine. The non-specific effects are probably more important than the specific effects for overall child survival and should be taken into consideration when vaccination policies are formulated. Based on current evidence6 and supported by this study, the recommendation to increase the age of MV to 12 months should be removed. It should also be considered changing policy from the current one-dose of MV to a two-dose schedule with the first dose being given earlier.17 However, the major future problem is what to do when measles infection has been eliminated or even eradicated. As long as we do not have a full understanding of the immunological mechanisms inducing beneficial non-specific effects and have not found alternative ways of inducing these effects, it would be unwise to remove the campaigns with MV27 28 and reduce the number of routine MV. MV has been the strongest promoter of better child health and it might cost dearly if we stopped or reduced the number of MVs.29

Footnotes

Contributors: The original examinations were conducted by LS and PA. Long-term follow-up was assured by CLM and AR. SWM, CSB and HR were responsible for the statistical analyses. The first draft was written by PA. All authors contributed to the final version of the paper. PA will act as the guarantor of the study.

Funding: The original project was funded by SIDA, Sweden. The reanalysis was supported by the Danish Council for Development Research, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark and Novo Nordisk. CSB holds a starting grant from the ERC (ERC-2009-StG-243149). CVIVA is supported by a grant from the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF108). The work on the non-specific effects of vaccines had European Union FP7 support for OPTIMUNISE (grant: Health-F3-2011-261375). PA held a research professorship grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Disclaimer: The funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The original study was conducted at the request of the Ministry of Health in Guinea-Bissau.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Aaby P, Whittle HC, Benn CS. Vaccine programmes must consider their effect on general resistance. BMJ 2012;344:e3769 10.1136/bmj.e3769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aaby P, Bukh J, Lisse IM et al. . Measles vaccination and reduction in child mortality: a community study from Guinea-Bissau. J Infect 1984;8:13–21. 10.1016/S0163-4453(84)93192-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aaby P, Bukh J, Lisse IM et al. . Measles mortality, state of nutrition, and family structure: a community study from Guinea-Bissau. J Infect Dis 1983;147:693–701. 10.1093/infdis/147.4.693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aaby P, Bukh J, Lisse IM et al. . Overcrowding and intensive exposure as determinants of measles mortality. Am J Epidemiol 1984;120:49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr 2006;(Suppl)450:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aaby P, Martins CL, Ravn H et al. . Is early measles vaccination better than later measles vaccination? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2015;109:16–28. 10.1093/trstmh/tru174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aaby P, Samb B, Andersen M et al. . No long-term excess mortality after measles infection: a community study from Senegal. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:1035–41. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaby P, Lisse I, Mølbak K et al. . No persistent T lymphocyte immunosuppression or increased mortality after measles infection: a community study from Guinea-Bissau. Pediatr Inf Dis J 1996;15:39–44. 10.1097/00006454-199601000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aaby P, Samb B, Simondon F et al. . Low mortality after mild measles infection compared to uninfected children in rural West Africa. Vaccine 2002;21:120–6. 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00430-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aaby P, Bhuyia A, Nahar L et al. . The survival benefit of measles immunisation may not be explained entirely by the prevention of measles disease. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:106–15. 10.1093/ije/dyg005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aaby P, Samb B, Simondon F et al. . Divergent mortality for male and female recipients of low-titer and high-titer measles vaccines in rural Senegal. Am J Epidemiol 1993;138:746–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desgrées du Loû A, Pison G, Aaby P. The role of immunizations in the recent decline in childhood mortality and the changes in the female/male mortality ratio in rural Senegal. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:643–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Soares-Weiser K, Reingold A. Systematic review of the non-specific effects of BCG, DTP and measles containing vaccines. http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/april (accessed 1 Jun 2014).

- 14.Aaby P, Martins CL, Garly ML et al. . Non-specific effects of standard measles vaccine at 4.5 and 9 months of age on childhood mortality: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c6495 10.1136/bmj.c6495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Kasongo Project Team. Influence of measles vaccination on survival pattern of 7–35-month-old children in Kasongo, Zaire. Lancet 1981;1:764–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapoor SK, Reddaiah VP. Effectiveness of measles immunization on diarrhea and malnutrition related mortality in 1–4-year-olds. Indian J Pediatr 1991;58:821–3. 10.1007/BF02825442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aaby P, Ibrahim SA, Libman MD et al. . The sequence of vaccinations and increased female mortality after high-titre measles vaccine: trials from rural Sudan and Kinshasa. Vaccine 2006;24:2764–71. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization. Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization. April 2014 - conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2014;89:221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaby P, Martins CL, Garly ML et al. . The optimal age of measles immunization in low-income countries: a secondary analysis of the assumptions underlying the current policy. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000761 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meeting of the immunization Strategic Advisory Group of experts, November 2006—conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2007;82:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aaby P, Martins CL, Garly ML et al. . Measles vaccination in the presence or absence of maternal measles antibody: impact on child survival. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:484–92. 10.1093/cid/ciu354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinnijenhuis J, Quintin J, Preijers F et al. . Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109:17537–42. 10.1073/pnas.1202870109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benn CS, Netea MG, Selin LK et al. . A small jab—a big effect: nonspecific immunomodulation by vaccines. Trends Immunol 2013;34:431–9. 10.1016/j.it.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh RM, Selin LK. No one is naïve: the significance of heterologous T-cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2002;2:417–26. 10.1038/nri820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen KJ, Søndergaard M, Andersen A et al. . A randomized trial of an early measles vaccine at 4½ months of age in Guinea-Bissau: sex-differential immunological effects. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e97536 10.1371/journal.pone.0097536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mina MJ, Metcalf CJ, de Swart RL et al. . Long-term measles-induced immunomodulation increases overall childhood infectious disease mortality. Science 2015;348:694–9. 10.1126/science.aaa3662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.FIsker AB, Rodrigues A, Martins C et al. . Reduced mortality after general measles vaccination campaign in rural Guinea-Bissau. Pediatr Inf Dis J 2015;34:1369–76. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byberg S, Thysen SM, Rodrigues A et al. . A general measles vaccination campaign and subsequent child mortality in urban Guinea-Bissau. Vaccine 2017;35:33–39. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aaby P, Samb B, Simondon F et al. . Non-specific beneficial effect of measles immunisation: analysis of mortality studies from developing countries. BMJ 1995;311:481–5. 10.1136/bmj.311.7003.481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011317supp.pdf (51.7KB, pdf)