Abstract

Objective

The annual outbreak of influenza is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality among the elderly population around the world. While there is an annual vaccine available to prevent or reduce the incidence of disease, not all older people in Korea choose to be vaccinated. There have been few previous studies to examine the factors influencing influenza vaccination in Korea. Thus, this study identifies nationwide factors that affect influenza vaccination rates in elderly Koreans.

Methods

We obtained data from the Fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2009 (KNHANES IV), a nationwide health survey in Korea. To assess influenza vaccination status, we analysed answers to a single question from the survey. From the respondents, we selected 3567 elderly population aged 65 years or older, to analyse the effects of variables including sociodemographic, health behavioural risk, health status and psychological factors on vaccination coverage. We identified factors that affect vaccination status using a multiple logistic regression analysis.

Results

The rate of influenza vaccination in this elderly population was 75.8%. Overall, the most significant determinants for choosing influenza vaccination were a recent history of health screening (adjusted OR (aOR) 2.26, 95% CI 1.92 to 2.66) and smoking (aOR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.98). Other contributing factors were age, household income, marital status, alcohol consumption, physical activity level, self-reported health status and a limitation in daily activities. In contrast, psychological factors, including self-perceived quality of life, stress and depressive mood, did not show close association with vaccination coverage.

Conclusions

To boost influenza vaccination rates in the elderly, an influenza campaign should focus on under-represented groups, especially smokers. Additionally, promoting routine health screening for the elderly may be an efficient way to help achieve higher vaccination rates. Our results highlight the need for a new strategy for the vaccination campaign.

Keywords: influenza, vaccination, elderly, factors

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The results of this study highlight potential factors associated with undervaccination among the elderly, which has an important public health implication for improving vaccination rates.

A cross-sectional study with a sample size of 3567 collected from a national health survey.

Assessment of nationwide factors associated with influenza vaccination in an elderly population.

Main limitations include a possible recall bias and having no further verification of vaccination status.

The generalisability of the study results might be limited due to the gender bias among the participants.

Introduction

Influenza is a highly contagious, viral, acute respiratory illness associated with elevated morbidity and mortality, particularly among high-risk individuals, including the elderly and those with underlying chronic diseases.1–3 The influenza mortality may be underestimated since influenza is not commonly recognised as a cause of mortality in the elderly.4–6 Despite this, around 90% of the influenza mortality occurs in people aged 65 years and older.7 This suggests that the elderly is one of the groups with the highest risk for serious complications in influenza.

Many studies have documented that influenza vaccination is a safe and cost-effective way of preventing influenza and pneumonia in the elderly and children.8–12 Annual influenza vaccinations have been shown to significantly reduce hospitalisations and mortality in older population.13 14 For this reason, the World Health Assembly encourages member states to increase influenza vaccination coverage for high-risk populations to 50% by 2006 and 75% by 2010.15 Additionally, the US department of Health and Human Services (HHS) targeted a minimum vaccination rate of 90% for people aged 65 years and older in 2010.16 In South Korea, the Korea Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) clearly recommend that annual influenza vaccinations are encouraged for all people aged 65 years or older and aimed to achieve a vaccination coverage >60% for this priority group.17

Some authors have reported that the estimated influenza vaccination coverage among the elderly in 2004–2005 was 77.2–79.9%.18 19 While this result surpassed the KCDC's goal, some discrepancies in coverage rate were observed between different groups within the elderly, and thus efforts to achieve better coverage for specific groups, such as those with low household income, and smokers, are still needed.17 In other countries, many authors also report that such discrepancies also exist within their populations.20–29 To improve coverage among under-represented populations, factors hindering vaccination acceptance should be identified and addressed.

Worldwide, acceptance of influenza vaccination across all age groups has been found to be associated with numerous factors, such as gender, age, educational level, marital status and recency of the last health check-up.24 29–39 Similarly, in South Korea, some previous studies have identified vaccination rates being influenced by these same factors.17–19 However, it appears that few studies have examined the nationwide elderly population of South Korea. Therefore, using the the Fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV), our study aimed to find determinants associated with influenza vaccination coverage within the elderly population and to address the limitations of Korea's ongoing vaccination campaign strategy.

Methods

Study population

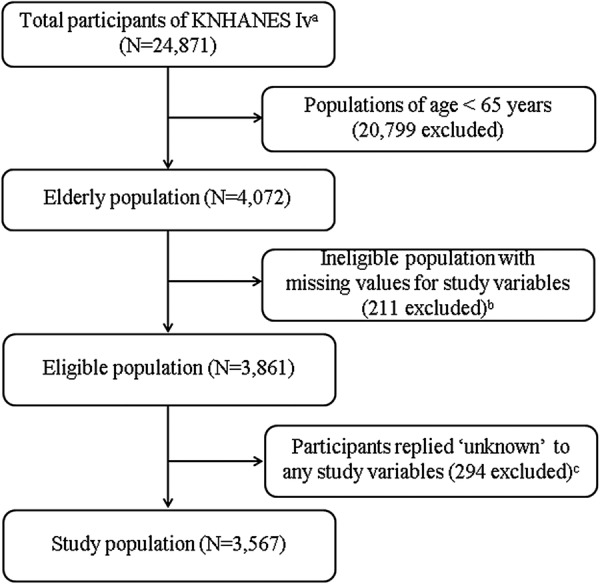

In this study, we used data obtained from the KNHANES IV (2007–2009) conducted by the KCDC. It is a nationwide survey representing the general population of Korea by population-based random sampling of 24 870 individuals across 600 national districts. For constructing the study sample in KNHANES IV, they carefully chose multiple households that represent their district via systematic sampling. Those chosen households received informed consent. The overall response rate of KNAHANES IV was 78.4%. The survey design includes stratified multistage probability sampling and includes comprehensive information on health status, health behaviour, quality of life and sociodemographics. After gaining informed consent, each survey respondent is interviewed face to face in their home by trained interviewers. From the source population of 24 871 individuals who participated in KNHANES IV, we first excluded the 20 799 individuals who were aged <65 years at the time of the survey. We then excluded 211 individuals whose responses to the study variables were missing. Finally, we excluded 294 individuals who responded ‘unknown’ to any of the study variables. This left a study population of 3567 (figure 1). Since the survey data used are publicly available, this study did not require the ethical approval of the Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

The study population framework. aThe Fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2009. bThe number of non-responders for vaccination status was zero. cThe number of responders for vaccination status as ‘unknown’ was zero.

Study variables

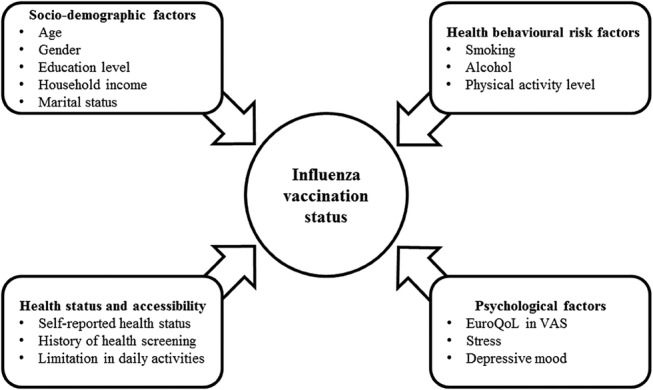

In the survey, influenza vaccination status was indicated by a single question ‘Have you been vaccinated against influenza during the past 12 months?’ and its answer (yes/no) was used as the dependent variable in our study. To identify possible factors associated with the influenza vaccination coverage, we categorised survey variables into four groups and chose potentially relevant variables for each group (figure 2). The four groups and their variables are as follows:

Figure 2.

Categorisation of the study variables in this study. VAS, visual analogue scale.

(1) Sociodemographic factors (age, sex, educational level, household income and marital status), (2) health behavioural risk factors (smoking status, alcohol consumption and physical activity level), (3) health status and accessibility factors (self-reported health status, a history of health screening in the past 2 years and a limitation in daily activities) and (4) psychological factors (the EuroQoL,40 41 stress and self-perceived depressive mood). We studied psychological factors because, although previous studies indicate that mental illness can affect vaccination coverage,42 43 very few previous papers that studied the determinants of influenza vaccination investigated the effects of different psychological factors.

Statistical analysis

We used univariate logistic regression to explore which factors of sociodemographics, behavioural risk, health status and accessibility, quality of life, and mental status were associated with an individual's influenza vaccination status. After a univariate logistic regression analysis, we used a multiple logistic analysis. The adjusted OR (aOR) and 95% CIs were calculated to show the strength of each association. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata V.12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).44

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of the study population are summarised in table 1. The population was equally divided into three age groups (65–69, 70–74 and ≥75 years). More women than men participated in the survey (40.7% men, 59.3% women) and around three-quarters of the participants were poorly educated (fewer than 6 years of formal education; 75.7%). Categorising household income into two groups (those earning US$<1000/month and those earning US$≥1000/month) divided the sample into about two approximately equal groups and more participants lived without a spouse (62.6%) than those who lived with one (37.4%). Additionally, most people were not current smokers (85.4%), drank little alcohol (68.5%) and never exercised (67.2%). In terms of health status and accessibility, most people reported that they felt unhealthy (44.4%) and most had undergone a recent health screening (55.2%). Generally, people had high scores (58.7% with ≥61) in the EuroQoL visual analogue system and reported that they frequently felt stressed (75.9%) and had recently felt that their mood had been depressive (78.6%). The univariate logistic analysis of factors associated with influenza vaccination status is presented in table 2. We found that people were more likely to be vaccinated as they aged (70.3% for 65–69 years vs 79.3% for ≥75 years) and when they categorised themselves as unhealthy (78.1% for those who reported themselves as unhealthy vs 73.4% for those who reported themselves as healthy). Smokers showed the lowest vaccination coverage with only 69.3% choosing vaccination. In contrast, the group which had recently undergone health screening showed the highest rate of vaccination (81.9%). Individuals who seldom engaged in physical activity showed lower vaccination rates than individuals from other physical activity levels. No significant associations with psychological factors were observed. In the univariate study, the factors that correlated most strongly with vaccination coverage were recent history of health screening (vaccinated percentage 81.9%, OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.81 to 2.47), age (vaccinated percentage 79.3%, OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.34 to 1.95 for ≥75 years and vaccinated percentage 78.8%, OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.89 for 70–74 years) and moderate physical activity (vaccinated percentage 79.5%, OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.63).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population, The Fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2009 (n=3567)

| Variable | n | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| 65–69 | 1326 | 37.2 |

| 70–74 | 1122 | 31.4 |

| ≥75 | 1119 | 31.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1450 | 40.7 |

| Female | 2117 | 59.3 |

| Education level | ||

| Elementary school (≤6 years) | 2700 | 75.7 |

| More than elementary school | 867 | 24.3 |

| Household income* | ||

| US$<1000 per month | 1648 | 46.2 |

| US$≥1000 per month | 1919 | 53.8 |

| Marital status† | ||

| Living with spouse | 2233 | 62.6 |

| Living without spouse | 1334 | 37.4 |

| Health behavioural risks | ||

| Smoking | ||

| Not current smoker or never-smoker | 3046 | 85.4 |

| Current smoker | 521 | 14.6 |

| Alcohol | ||

| Less than once per month or never tried | 2442 | 68.5 |

| More than once per month | 1125 | 31.5 |

| Physical activity level | ||

| Never | 2398 | 67.2 |

| More than once per week | 743 | 20.8 |

| Everyday | 426 | 12.0 |

| Health status and accessibility | ||

| Self-reported health status | ||

| Unhealthy | 1583 | 44.4 |

| Fair | 847 | 23.7 |

| Healthy | 1137 | 31.9 |

| History of health screening‡ | ||

| No | 1598 | 44.8 |

| Yes | 1969 | 55.2 |

| Limitation in daily activities | ||

| No | 1974 | 55.3 |

| Yes | 1593 | 44.7 |

| Psychological factors | ||

| EuroQoL in VAS | ||

| ≤30 | 304 | 8.5 |

| 31–60 | 1171 | 32.8 |

| ≥61 | 2092 | 58.7 |

| Stress | ||

| Frequently | 2706 | 75.9 |

| Rarely | 861 | 24.1 |

| Depressive mood§ | ||

| Frequently | 2805 | 78.6 |

| Rarely | 762 | 21.4 |

*US$1000=1 million Korean won (US$1=KRW1000).

†The term ‘spouse’ refers to an individual who is legally married, or cohabiting and ‘without spouse’ refers to an individual who is single, divorced or separated.

‡Health screening refers to national healthcare services conducted within 2 years.

§Depressive mood lasted longer than 2 weeks in a year.

VAS, visual analogue scale.

Table 2.

Factors associated with influenza vaccination status in univariate logistic regression analysis (n=3567)

| Univariate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Vaccinated (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| 65–69 | 70.3 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| 70–74 | 78.8 | 1.57 (1.30 to 1.89) | <0.001 |

| ≥75 | 79.3 | 1.61 (1.34 to 1.95) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 75.0 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Female | 76.3 | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.25) | 0.391 |

| High education* | 77.9 | 1.16 (0.97 to 1.40) | 0.101 |

| High household income† | 76.9 | 1.14 (0.98 to 1.33) | 0.087 |

| Living alone‡ | 74.6 | 0.90 (0.77 to 1.06) | 0.2 |

| Health behavioural risks | |||

| Current smoking | 69.3 | 0.68 (0.55 to 0.83) | <0.001 |

| Frequent drinking§ | 73.5 | 0.84 (0.71 to 0.98) | 0.032 |

| Physical activity level | |||

| Never | 74.5 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| More than once per week | 79.5 | 1.33 (1.09 to 1.63) | 0.005 |

| Everyday | 76.5 | 1.11 (0.88 to 1.42) | 0.37 |

| Health status and accessibility | |||

| Self-reported health status | |||

| Unhealthy | 78.1 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Fair | 74.5 | 0.82 (0.67 to 0.99) | 0.042 |

| Healthy | 73.4 | 0.77 (0.65 to 0.92) | 0.005 |

| History of health screening¶ | 81.9 | 2.11 (1.81 to 2.47) | <0.001 |

| Limitation in daily activities | 78.0 | 1.24 (1.06 to 1.45) | 0.006 |

| Psychological factors | |||

| High EuroQoL: VAS | |||

| ≤30 | 75.7 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| 31–60 | 77.1 | 1.08 (0.81 to 1.46) | 0.592 |

| ≥61 | 75.0 | 0.97 (0.73 to 1.28) | 0.818 |

| Stressed | 74.3 | 0.90 (0.76 to 1.08) | 0.256 |

| Frequent depressive mood** | 74.9 | 0.94 (0.78 to 1.14) | 0.54 |

*‘Well education’ refers to those who studied in an elementary school.

†‘High household income’ refers to an income of more than 1 million won per month.

‡‘Living alone’ refers to an individual who is single, divorced or separated.

§Frequent drinking is defined by drinking more than once per week.

¶Health screening refers to national healthcare services conducted within 2 years.

**Depressive mood lasted longer than 2 weeks in a year.

VAS, visual analogue scale.

The multiple logistic regression analysis is presented in table 3. The results of the multiple logistic regression analysis were generally similar to those of the univariate study, and showed that the factors with the two highest aORs were age (2.06, 95% CI 1.68 to 2.52 for 70–74 years) and recent history of health screening (2.26, 95% CI 1.92 to 2.66). The factor with the lowest aOR was current smoking status (0.78, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.98).

Table 3.

Factors associated with influenza vaccination status in multiple logistic regression analysis (n=3567)

| Multiple |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Vaccinated (%) | aOR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| 65–69 | 70.3 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| 70–74 | 78.8 | 1.79 (1.48 to 2.17) | <0.001 |

| ≥75 | 79.3 | 2.06 (1.68 to 2.52) | <0.001 |

| High education* | 77.9 | 1.27 (1.03 to 1.57) | 0.025 |

| High household income† | 76.9 | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.33) | 0.143 |

| Living alone‡ | 74.6 | 0.82 (0.68 to 1.00) | 0.045 |

| Health behavioural risks | |||

| Current smoking | 69.3 | 0.78 (0.62 to 0.98) | 0.03 |

| Frequent drinking§ | 73.5 | 0.86 (0.72 to 1.04) | 0.124 |

| Physical activity level | |||

| Never | 74.5 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| More than once per week | 79.5 | 1.29 (1.05 to 1.59) | 0.017 |

| Health status and accessibility | |||

| Self-reported health status | |||

| Unhealthy | 78.1 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Fair | 74.5 | 0.85 (0.68 to 1.06) | 0.144 |

| Healthy | 73.4 | 0.79 (0.64 to 0.97) | 0.025 |

| History of health screening¶ | 81.9 | 2.26 (1.92 to 2.66) | <0.001 |

| Limitation in daily activities | 78.0 | 1.18 (0.99 to 1.41) | 0.072 |

*‘High education’ refers to those who studied in an elementary school.

†‘High household income’ refers to an income of more than 1 million won per month.

‡‘Living alone’ refers to an individual who is single, divorced or separated.

aOR, adjusted OR; VAS, visual analogue scale. §Frequent drinking is defined by drinking more than once per week. ¶Health screening refers to national healthcare services conducted within 2 years.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify which factors are associated with recent vaccination against influenza within Korea via the results of the representative sample of the Korean population by the KNHANES. The influenza vaccination coverage rate in 2007–2009 among elderly Koreans was 75.8%. This result is above both the KCDC goal of 60%17 and the WHO goal of 75% vaccination coverage among the elderly by 2010.4 However, while the overall vaccination rate among the elderly surpasses these targets, certain populations—such as the younger elderly (70.3% in 65–69 years), those living alone (74.6%), smokers (69.3%), frequent drinkers (73.5%), those lacking physical activity (74.5%) and those regarding themselves as healthy (73.4%)—showed lower vaccination coverage than the WHO recommends. This indicates an uneven distribution of vaccination coverage within the elderly population.

Sociodemographic factors

Well-known factors that affect increased vaccination coverage are older age, higher education, higher household income and living alone.11 14 30 33 34 This suggests that future health policies should concentrate on encouraging younger groups to reach the WHO vaccination rate goal. Living alone reduces vaccination coverage, whereas high household income leads to more coverage. It is common to think that higher education and household wealth ensure both improved social status and greater access to health services. However, for those with high education and high incomes, living alone may reduce their chances of choosing vaccination. Therefore, healthcare professionals should in particular focus on the elderly who live alone.

Health behavioural risks

In this study, smoking was the most negatively influencing factor (aOR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.98). Smoking and alcohol consumption are again well-studied variables that negatively influence vaccination coverage.17 30 34 This implies that smokers among the elderly are the least protected population even though they are one of the highest risk groups facing influenza infection. In theory, smokers naturally could have more pulmonary complications than non-smokers such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer or pneumonia.45–47 It is plausible that people with more comorbidities have a higher chance of visiting hospitals and receiving vaccination recommendations. However, our study showed an opposite result. The same tendency is observed among those who frequently consume alcohol. Therefore, healthcare professionals should encourage such people to get vaccinations.

Health status and accessibility

A history of recent health screening was the factor most positively associated with vaccination (aOR 2.26, 95% CI 1.68 to 2.52). In contrast, a self-perception of better health was the factor most negatively associated with vaccination (aOR 0.79, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.97). Previous studies have clearly demonstrated that vaccination rates can be increased through health screening or recommendations from doctors.34 Our results suggest that many elderly people who regard themselves as healthy are not motivated to have a vaccination unless they are encouraged to visit a physician. The positive effects of health screening on vaccination coverage may be due to the national health policy that provides free influenza vaccinations to the vulnerable elderly at public health centres.18 Since the National Cancer Screening Program of the National Cancer Centre in Korea targets the elderly, it is also possible that people who used this service received a recommendation from a physician to accept an influenza vaccine. Thus, healthcare professionals should be reminded that a recommendation from a physician is one of the most successful strategies for improving vaccination coverage among the elderly.

Psychological factors

According to Lorenz et al,43 the vaccination rate among the mentally ill population is lower than that in the general population. This suggests that psychological factors, such as a stressed or depressive mood, may be associated with vaccination coverage. In our study, no psychological variables—including being stressed, a depressive mood or the respondent's perceived quality of life—were significantly associated with vaccination coverage. This discrepancy might be due to a cultural difference between study sites, the willingness of respondents to report mental illness, limitations of sample size among the non-vaccinated population or other factors not considered in the multivariable model.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, some respondents of KHNANES IV were interviewed during the summer and this may have led to a recall bias since most vaccination campaigns are generally conducted during a couple of months in autumn. For example, if a respondent had a vaccination last autumn, it is possible that he or she forgot their vaccination status at the time of the survey. Therefore, the vaccination rate is potentially underestimated. Second, there might be a significant gender bias (male 40.7% vs female 59.3%) because it was easier for housewives to visit the interviewers compared with other family members who were all invited to complete the survey during the daytime. The gender bias suggests that women were more likely to participate in this survey. Third, the collinearity between presumed independent variables (sociodemographic factors, health behavioural risk factors, health status and accessibility factors, and psychological factors) was not examined thoroughly, and possible dependency between variables may have undermined the integrity of the result.

Conclusion

Although the influenza vaccination rate in elderly Koreans reached the WHO target coverage rate, more should be done to increase the vaccination rate for under-represented populations, such as those with low household income, those who live alone, smokers, people who frequently consume alcohol and, in particular, people who have not recently undergone a health screening. The results of this study may help to guide health professionals in their design of a better strategy to encourage influenza vaccination among the elderly.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Adrian Laurenzi and Diana Post for English proofreading.

Footnotes

Contributors: SMP provided substantial contributions to the study design. DSK was involved in analysis of data. All authors were involved in interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. SMP was involved in final approval of the version to be published. All authors provided agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately resolved.

Funding: KK received a scholarship from the BK21-plus education programme provided by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Williamson GD et al. The impact of influenza epidemics on mortality: introducing a severity index. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1944–50. 10.2105/AJPH.87.12.1944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hak E, Nordin J, Wei F et al. Influence of high-risk medical conditions on the effectiveness of influenza vaccination among elderly members of 3 large managed-care organizations. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann AG, Mangtani P, Russell CA et al. The impact of targeting all elderly persons in England and Wales for yearly influenza vaccination: excess mortality due to pneumonia or influenza and time trend study. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e002743 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans MR, Watson PA. Why do older people not get immunised against influenza? A community survey. Vaccine 2003;21:2421–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baltussen RM, Reinders A, Sprenger MJ et al. Estimating influenza-related hospitalization in the Netherlands. Epidemiol Infect 1998;121:129–38. 10.1017/S0950268898008966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castilla J, Arregui L, Baleztena J et al. [Incidence of influenza and influenza vaccine effectiveness in the 2004–2005 season]. An Sist Sanit Navar 2006;29:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordin J, Mullooly J, Poblete S et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing hospitalizations and deaths in persons 65 years or older in Minnesota, New York, and Oregon: data from 3 health plans. J Infect Dis 2001;184:665–70. 10.1086/323085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitman RJ, White LJ, Sculpher M. Estimating the clinical impact of introducing paediatric influenza vaccination in England and Wales. Vaccine 2012;30:1208–24. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitman RJ, Nagy LD, Sculpher MJ. Cost-effectiveness of childhood influenza vaccination in England and Wales: results from a dynamic transmission model. Vaccine 2013;31:927–42. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichol KL, Margolis KL, Wuorenma J et al. The efficacy and cost effectiveness of vaccination against influenza among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 1994;331:778–84. 10.1056/NEJM199409223311206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scuffham PA, West PA. Economic evaluation of strategies for the control and management of influenza in Europe. Vaccine 2002;20:2562–78. 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00154-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brydak L, Roiz J, Faivre P et al. Implementing an influenza vaccination programme for adults aged >/=65 years in Poland: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Clin Drug Investig 2012;32:73–85. 10.2165/11594030-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Govaert TM, Thijs CT, Masurel N et al. The efficacy of influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. JAMA 1994;272:1661–5. 10.1001/jama.1994.03520210045030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross PA, Hermogenes AW, Sacks HS et al. The efficacy of influenza vaccine in elderly persons. A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:518–27. 10.7326/0003-4819-123-7-199510010-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Organization WH. Influenza vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2005;33:279–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shalala DE, Satcher D. Healthy people, 2010: conference edition. DIANE Publishing, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryu SY, Kim SH, Park HS et al. Influenza vaccination among adults 65 years or older: a 2009–2010 community health survey in the Honam region of Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:4197–206. 10.3390/ijerph8114197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kee SY, Lee JS, Cheong HJ et al. Influenza vaccine coverage rates and perceptions on vaccination in South Korea. J Infect 2007;55:273–81. 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.04.354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim JW, Eom CS, Kim KH et al. Coverage of influenza vaccination among elderly in South Korea: a population-based cross sectional analysis of the season 2004–2005. J Korean Geriatr Soc 2009;13:215–21. 10.4235/jkgs.2009.13.4.215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quach S, Hamid JS, Pereira JA et al. Influenza vaccination coverage across ethnic groups in Canada. CMAJ 2012;184:1673–81. 10.1503/cmaj.111628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Baz I, Aguilar I, Moran J et al. Factors associated with continued adherence to influenza vaccination in the elderly. Prev Med 2012;55:246–50. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams WW, Lu PJ, Lindley MC et al. , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza vaccination coverage among adults—National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2008–09 influenza season. MMWR Suppl 2012;61:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jimenez-Garcia R, Hernndez-Barrera V, Rodriguez-Rieiro C et al. Are age-based strategies effective in increasing influenza vaccination coverage? The Spanish experience. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2012;8:228–33. 10.4161/hv.18433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.La Torre G, Iarocci G, Cadeddu C et al. Influence of sociodemographic inequalities and chronic conditions on influenza vaccination coverage in Italy: results from a survey in the general population. Public Health 2010;124:690–7. 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blank PR, Schwenkglenks M, Szucs TD. Influenza vaccination coverage rates in five European countries during season 2006/07 and trends over six consecutive seasons. BMC Public Health 2008;8:272 10.1186/1471-2458-8-272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindley MC, Wortley PM, Winston CA et al. The role of attitudes in understanding disparities in adult influenza vaccination. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:281–5. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singleton JA, Santibanez TA, Wortley PM. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination of adults aged > or = 65: racial/ethnic differences. Am J Prev Med 2005;29:412–20. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Topuzoglu A, Ozaydin GA, Cali S et al. Assessment of sociodemographic factors and socio-economic status affecting the coverage of compulsory and private immunization services in Istanbul, Turkey. Public Health 2005;119:862–9. 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horby PW, Williams A, Burgess MA et al. Prevalence and determinants of influenza vaccination in Australians aged 40 years and over—a national survey. Aust N Z J Public Health 2005;29:35–7. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2005.tb00745.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Endrich MM, Blank PR, Szucs TD. Influenza vaccination uptake and socioeconomic determinants in 11 European countries. Vaccine 2009;27:4018–24. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamal KM, Madhavan SS, Amonkar MM. Determinants of adult influenza and pneumonia immunization rates. J Am Pharm Assoc 2003;43:403–11. 10.1331/154434503321831120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaux S, Van Cauteren D, Guthmann JP et al. Influenza vaccination coverage against seasonal and pandemic influenza and their determinants in France: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2011;11:30 10.1186/1471-2458-11-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shahrabani S, Benzion U. The effects of socioeconomic factors on the decision to be vaccinated: the case of flu shot vaccination. Isr Med Assoc J 2006;8:630–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landi F, Onder G, Carpenter I et al. Prevalence and predictors of influenza vaccination among frail, community-living elderly patients: an international observational study. Vaccine 2005;23:3896–901. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez Callejas A, Campins Marti M, Martinez Gomez X et al. [Influenza vaccination in patients admitted to a tertiary hospital. Factors associated with coverage]. An Pediatr (Barc) 2006;65:331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez-Rieiro C, Esteban-Vasallo MD, Dominguez-Berjon MF et al. Coverage and predictors of vaccination against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza in Madrid, Spain. Vaccine 2011;29:1332–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tuppin P, Choukroun S, Samson S et al. [Vaccination against seasonal influenza in France in 2010 and 2011: decrease of coverage rates and associated factors]. Presse Med 2012;41:e568–76. 10.1016/j.lpm.2012.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu SS, Yang P, Li HY et al. [The coverage rate and obstructive factors of influenza vaccine inoculation among residents aged above 18 years in Beijing from 2007 to 2010]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2011;45:1077–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santos-Sancho JM, Lopez-de Andres A, Jimenez-Trujillo I et al. Adherence and factors associated with influenza vaccination among subjects with asthma in Spain. Infection 2013;41:465–71. 10.1007/s15010-013-0414-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.EuroQol G. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinto Prades JL. A European measure of health: the EuroQol. Rev Enferm 1993;16:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wheelock A, Thomson A, Sevdalis N. Social and psychological factors underlying adult vaccination behavior: lessons from seasonal influenza vaccination in the US and the UK. Expert Rev Vaccines 2013;12:893–901. 10.1586/14760584.2013.814841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorenz RA, Norris MM, Norton LC et al. Factors associated with influenza vaccination decisions among patients with mental illness. Int J Psychiatry Med 2013;46:1–13. 10.2190/PM.46.1.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boston RC, Sumner AE. STATA: a statistical analysis system for examining biomedical data. Adv Exp Med Biol 2003;537:353–69. 10.1007/978-1-4419-9019-8_23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishii Y. Smoking and respiratory diseases. Nihon Rinsho 2013;71:416–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khuder SA. Effect of cigarette smoking on major histological types of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2001;31:139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bartal M. COPD and tobacco smoke. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2005;63:213–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]