Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of active treatment targeted at underlying disease (TTD)/potentially curative treatments versus palliative care (PC) in improving overall survival (OS) in terminally ill patients.

Design

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCT). Methodological quality of included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

Data sources

Medline and Cochrane databases were searched, with no language restriction, from inception to 19 October 2016.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Any RCT assessing the efficacy of any active TTD versus PC in adult patients with terminal illness with a prognosis of <6-month survival were eligible for inclusion.

Results

Initial search identified 8252 citations of which 10 RCTs (15 comparisons, 1549 patients) met inclusion criteria. All RCTs included patients with cancer. OS was reported in 7 RCTs (8 comparisons, 1158 patients). The pooled results showed no statistically significant difference in OS between TTD and PC (HR (95% CI) 0.85 (0.71 to 1.02)). The heterogeneity between pooled studies was high (I2=62.1%). Overall rates of adverse events were higher in the TTD arm.

Conclusions

Our systematic review of available RCTs in patients with terminal illness due to cancer shows that TTD compared with PC did not demonstrably impact OS and is associated with increased toxicity. The results provide assurance to physicians, patients and family that the patients' survival will not be compromised by referral to hospice with focus on PC.

Keywords: End of life care, PALLIATIVE CARE, Terminal illness

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review of randomised controlled trials to assess the benefits and risks associated with active treatment targeted at underlying disease versus palliative in the end-of-life setting.

One of the strengths of this study was the extensive, systematic literature search performed to identify all available randomised controlled trials in terminally ill patients.

A limitation of this systematic review is the availability of small number of studies with overall survival data.

Introduction

The diagnosis of a terminal illness for patients is shattering news.1 Following the diagnosis, patients along with their families are faced with several complex decisions relating to medical, spiritual, legal, or existential issues.1 The most concerning decision for patients and families alike following diagnosis of terminal illness relates to the choice of medical strategy of either opting for active treatment targeted at underlying disease (TTD) which can potentially be life-prolonging or curative, versus palliative care (PC) where the primary focus is on providing symptomatic relief and improving quality of life (QOL).2 The US Medicare regulations recommend PC for patients with terminal illness, ideally in hospice setting, if the expected survival is <6 months; conversely, PC or referral to hospice is considered inappropriate if expected survival is <6 months. However, findings from several studies show that application of these recommendations is far from optimal in real-life setting. For example, around 40% of patients with advanced lung cancer continued aggressive therapy through the final month of life.3 Overall, over 60% of patients with cancer receive aggressive TTD within the past 3 months of life.4–7 In fact, during the last decade, the number of patients receiving aggressive therapy within the last month of life grew8 which also reflects the increased healthcare spending in the past 6 months of life. On the other hand, use of hospice in the past 3 days of life minimally increased from 14.3% to 17%.2 9 10 In short, patients with terminal illness are not receiving care as per the professional societies' or Medicare recommendations.2

There are several reasons for not delivering the appropriate care to patients with terminal illness. One of the main reasons is lack of evidence or conflicting evidence related to benefits and harms associated with TTD versus PC.2 Findings from a randomised controlled trial (RCT) assessing the role of supportive care versus supportive care in addition to TTD in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of urothelial tract demonstrated no survival advantage with a combination treatment approach.11 Another study by Schmid et al12 which assessed the role of radiotherapy or chemotherapy (ie, TTD) compared with no treatment in patients with inoperable squamous carcinoma of the oesophagus showed no survival advantage with TTD. However, results from a RCT comparing supportive care versus supportive care plus TTD in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer showed a survival advantage with TTD.13

Given that physicians are not accurate in establishing patients' prognosis for course of disease or death,14 15 to make informed choice, patients and physicians alike need reliable evidence on benefits and risks associated with TTD versus PC. Accordingly, we performed a systematic review with a goal to synthesise all available evidence to reliably assess the efficacy and safety of TTD compared with PC in patients with terminal illness (with expected survival of <6 months).

Methods

This systematic review was performed according to a prespecified protocol and is reported according to PRISMA guidelines.16

Eligibility criteria

Any RCT enrolling patients with clearly stated predicted median survival of <6 months comparing an established TTD versus PC alone was eligible for inclusion. Studies of novel TTD treatments within a context of clinical trials were excluded. We also excluded trials comparing add-on PC to two active treatments. The distinction between PC versus TTD was made based on the original investigators intent (ie, symptom management vs curative or life prolonging intent) as stated in the introduction or methods of included studies.

Search and study selection

A comprehensive search of Medline and Cochrane electronic databases, with no language restriction, was undertaken from inception to 19 October 2016. Search strategy is provided in online supplementary appendix 1. Two authors (AK and TR) reviewed all retrieved titles/abstracts and full-text articles independently. A third author (BD) reviewed any disagreements to arrive at consensus.

bmjopen-2016-014661supp_appendix.pdf (181.5KB, pdf)

Data collection

Data were abstracted on study and patient characteristics, treatment, and outcomes (overall survival (OS), QOL, treatment-related mortality (TRM), and adverse events). Data extraction was performed independently by two authors (TR and FAK) using a standardised data extraction form. The corresponding author (BD) resolved any disagreement during the data extraction process. Risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.17 The overall assessment of methodological quality was performed using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology.18

Statistical analysis

When appropriate, data were pooled for each outcome. Dichotomous data were summarised using risk ratio (RR) based on the number of events and total number of participants and pooled under random-effects model. In regards to time-to-event data, HR and 95% CIs were extracted, whenever reported. Otherwise, total number of participants and events per arm and the p value were obtained in order to calculate the observed minus expected value (O-E) and variance as per method by Tierney et al.19 Time-to-event data were pooled using generic inverse variance under the random-effects model. All data are reported with 95% CI. Calculation of the I2 statistic was used to assess for heterogeneity. An I2 <30% was considered low heterogeneity, between 30% and 50% moderate heterogeneity and over 50% high heterogeneity.20 The analyses were performed using Review Manager software (Review Manager (RevMan) [program]. Version 5.3 version. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Results

Study selection

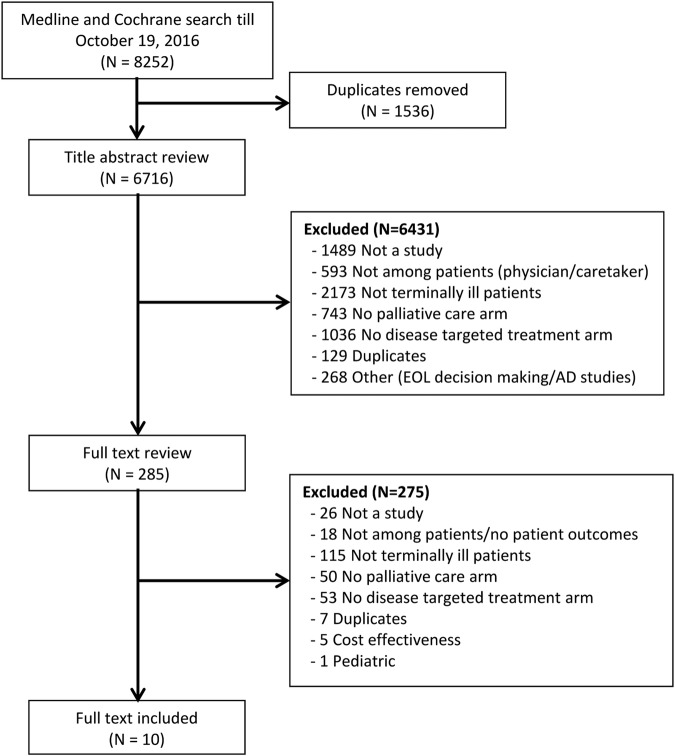

The initial search identified 8252 articles of which 10 RCTs (15 comparisons, 1549 patients) met the inclusion criteria.11–13 21–27 The study selection process is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the identification and selection of eligible studies for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Characteristics of included studies

As illustrated in table 1, all included studies enrolled patients with cancer. The majority of studies compared disease-targeted chemotherapy (12/15 comparisons) to PC alone11–13 21–26 while the remaining three studies used targeted drug therapy,27 radiotherapy,12 and hormone therapy26 on the TTD arm. The PC arm mainly consisted of analgesics (8/15 comparisons),11 13 22 25 26 blood product transfusions (7/15 comparisons),11 13 23 25–27 and palliative radiotherapy (5/15 comparisons).13 22 23

Table 1.

Study and patient characteristics

| Study, year | Years | Patients enrolled | Cancer type | Age (TTD vs PC) | TTD | PC offered in addition to TTD | PC | Expected median survival <6 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bellmunt, 2009 | 2003–2006 | 337 | Urothelial | NR | Chemotherapy | Yes | Pain medication, palliative chemotherapy, supportive care, antibiotics, corticosteroids | Yes |

| Cartei, 1993 | NR | 102 | Lung | Median (range): 57 (39–71) vs 56 (41–73) | Chemotherapy | Yes | Pain medication, radiotherapy, supportive care | Yes |

| Ciuleanu, 2009 | 2004–2006 | 303 | Pancreatic | Median (range): 58 (27–78) vs 57 (29–80) | Chemotherapy | Yes | Pain medication, supportive care, appetite stimulators | Yes |

| De Marinis, 1999a | 1990–1993 | 61 | Lung | NR | Chemotherapy | Unclear | Pain medication, radiotherapy, steroids, progestins | Yes |

| De Marinis, 1999b | 1990–1993 | 63 | Lung | NR | Chemotherapy | Unclear | Pain medication, radiotherapy, steroids, progestins | Yes |

| De Marinis, 1999c | 1990–1993 | 64 | Lung | NR | Chemotherapy | Unclear | Pain medication, radiotherapy, steroids, progestins | Yes |

| Lissoni, 1994a | NR | 50 | Pancreatic | Median (range): 56 (39–71) vs 57 (50–74) | Chemotherapy | Yes | Pain medication, supportive care, steroids, antiemetics, ansioliticos | Yes |

| Lissoni, 1994b | NR | 50 | Solid tumors | Median (range): 56 (38–72) vs 58 (42–71) | Drug therapy | Yes | Supportive care | Yes |

| Ranson, 2000 | 1995–1997 | 157 | Lung | Median (range): 65 (37–78) vs 64 (23–82) | Chemotherapy | Yes | Radiotherapy, supportive care, corticosteroids, antibiotics, antiemetics | Yes |

| Schmid, 1993a | 1987–1989 | 87 | Esophageal | Median: 55 vs 53 | Radiotherapy | Unclear | Intubation only | Yes |

| Schmid, 1993b | 1987–1989 | 86 | Esophageal | Median: 55 vs 53 | Chemotherapy | Unclear | Intubation only | Yes |

| Selawry, 1977a | NR | 150 | Lung | Median: 62 vs 59 | Chemotherapy | Unclear | NR | Yes |

| Selawry, 1977b | NR | 152 | Lung | Median: 59 vs 59 | Chemotherapy | Unclear | NR | Yes |

| Xinopoulos, 2008 | NR | 73 | Pancreatic | Mean (range): 66.5 (59–73) vs 66.6 (58–73) | Chemotherapy | Unclear | Plastic biliary endoprosthesis placement as needed | Yes |

NR, not reported; PC, palliative care; TTD, treatment targeted at underlying disease.

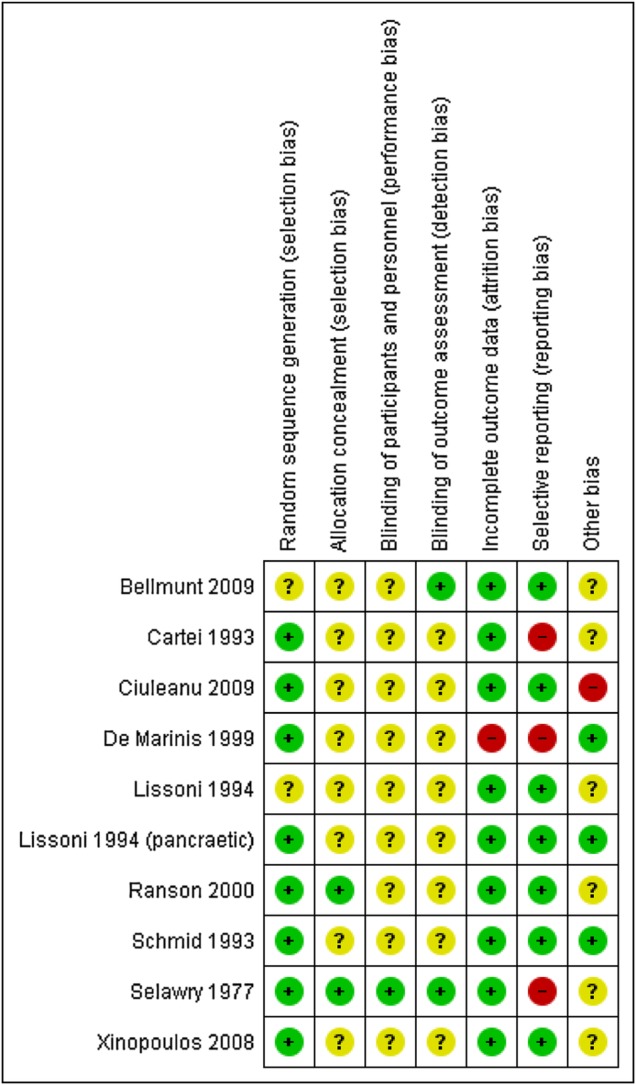

Risk of bias in included studies

The overall methodological quality of included studies ranged from moderate to low. As shown in figure 2, 80% of included studies (8/10) reported method of randomisation sequence generation. However, only 20% (2/10) of included studies were judged to have adequate allocation concealment and only 10% (1/10) involved blinding of participants/personnel or outcome assessors. Ninety per cent of studies (9/10) performed analysis as per intention-to-treat principle and 70% (7/10) studies reported all outcomes and did not involve selective reporting of outcomes.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias in included studies.

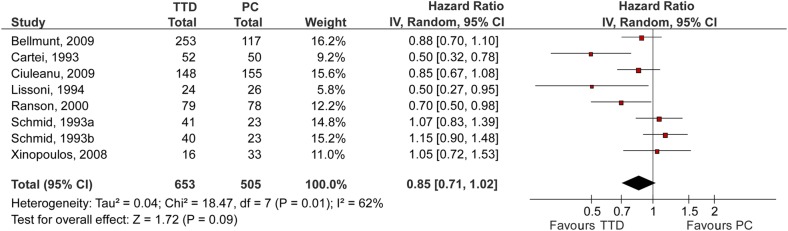

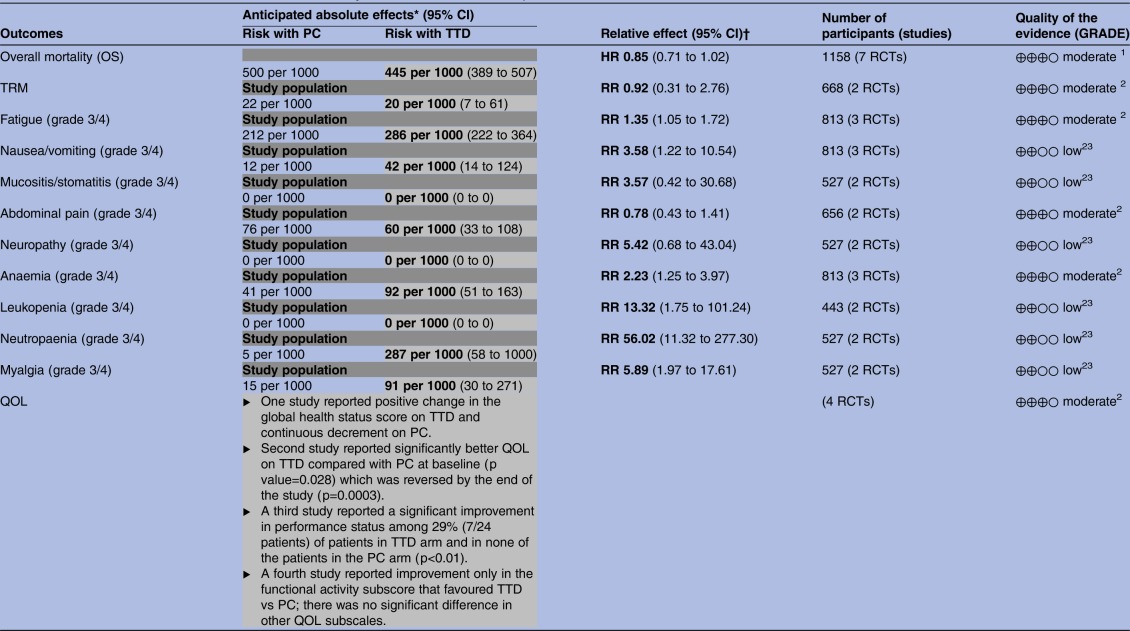

Outcomes

Patient outcomes are summarised in table 2. Figure 3 shows a forest plot comparing effects of TTD versus PC on the OS. OS was reported by seven RCTs (eight comparisons, 1158 patients).11–13 23–25 27 The pooled results showed no statistically significant difference in OS between TTD and PC (HR (95% CI) 0.85 (0.71 to 1.02)). The heterogeneity between pooled studies was high (I2=62.1%). Four studies included QOL as an outcome; however, data were not extractable for pooling.11 23 24 27 Only two RCTs (668 patients) reported TRM.11 25 There was no statistically significant difference in TRM between TTD and PC (RR (95% CI) 0.92 (0.31 to 2.76)). There was no heterogeneity between pooled studies (I2=0%). Seven RCTs (10 comparisons)11 13 22–26 discussed adverse events but only three (three comparisons)11 23 25 reported comparative data for both study arms. Overall, grade three or four adverse events were significantly more common on the TTD arm compared with PC (see table 2).

Table 2.

Evidence table for TTD versus PC alone in terminally ill adults GRADE evidence profile

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

1. High heterogeneity between studies.

2. Majority of studies not reporting data on outcome.

3. Wide CIs.

Any text which is either bold or in grey shading represents the risk associated with TTD.

*The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

†<1: Poorer results with PC; >1: poorer results with TTD; 1=no difference between effects of PC and TTD.

GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; OS, overall survival; PC, palliative care; QOL, quality of life; RCTs, randomised controlled trials; RR, risk ratio; TRM, treatment-related mortality; TTD, treatment targeted at underlying disease.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for overall survival. The summary estimate (HR) from individual studies is indicated by rectangles with lines representing the 95% CIs. The summary pooled estimate from all studies is represented by the diamond and the stretch of the diamond indicates the corresponding 95% CI. Summary estimates that fall to the left of the line (HR<1) indicate favourable survival on the treatment targeted at underlying disease (TTD) arm. Summary estimates that fall to the right of the line (HR>1) indicate favourable survival on the palliative care (PC) arm.

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review have several important implications for physicians, patients and policymakers. Physicians are obligated legally and ethically to provide patients with evidence on alternative management options in the end-of-life setting. Some states such as New York and California make the failure to discuss the management alternatives in terminal setting punishable by law (up to $5000 for repeated offences, and wilful violations by a jail term of up to 1 year).28 However, repeated assessments of the quality of decision-making in the end-of-life setting over the last two decades continue to show that is inadequate.1 In 2014, 55 million people died worldwide, the vast majority of whom did not receive adequate end-of-life care.29 The fundamental reason for this state of affairs is the lack of reliable estimates about the efficacy and safety of active treatment (TTD) versus PC in patients in terminal phase of their lives. Even though it is known that PC does improve survival when it is added to TTD,30 it is not known if TTD is superior to PC alone. Our systematic review fills this void. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review assessing the role of TTD compared with PC in patients with terminal illness with expected survival of <6 months. The findings showed that overall TTD compared with PC does not improve survival and is associated with significantly higher incidence of fatigue, nausea/vomiting, mucositis, grade III/IV neuropathy, anaemia, leukopenia, neutropaenia, and myalgia leading to poor QOL.

Decisions to discontinue with TTD and focus on PC are accompanied by an assessment that such treatments would be ineffective, potentially harmful or medically futile.2 Therefore, for patients and physicians our systematic review provides a long-awaited empirical answer on benefits and harms associated with TTD compared with PC. Based on research synthesis of all available randomised evidence, we found that patients with terminal illness and their physicians can avoid the impulse to ‘try anything or everything’ in desire to potentially prolong survival due to uncertainty if TTD is superior to PC. We demonstrated that this is not the case, and, in fact, TTD is typically more toxic. Our results, therefore, can be used to facilitate shared decision-making in end of life care setting, which is often difficult for physicians, patients and families. Our results may assist patients and physicians when making a decision on whether to continue or discontinue TTD and make an informed choice between TTD versus PC. Given that unrealistic patient and physician expectations are key barriers to improving the quality of end-of-life care,31 providing reliable evidence to ‘serve as a neutral arbiter’,32 our results may help assure patients, physicians and family members that focus on PC and hospice referral may not compromise the patient life expectancy but, in fact, result in higher quality of end-of-life care. If acted on, our findings may help improve referral to hospice; as stated above, over 16% of patients with cancer who die in hospice care are in hospice for <3 days while many do not receive hospice care at all.33 34 Similarly, our results may minimise unnecessary suffering as many patients with a terminal prognosis receive chemotherapy in the last month of life.35 Therefore, the findings from our systematic review may inform the referral to hospice for patients with terminal illness and avoid the late referrals to hospice; early referrals to hospice can help patients enjoy the full benefits of hospice care, more fulfilling remaining days of their lives while avoiding toxicity of unnecessary treatment. For policymakers, the evidence from this systematic review should promote a discussion on reimbursement practices where providers are more likely to be reimbursed for shared conversations with patients instead of administering aggressive therapy.36

Our study has several limitations, mainly due to selective outcome reporting and methodological quality of the primary studies eligible for this analysis. For example, of the 10 RCTs that met the inclusion criteria only 7 (eight comparisons) reported survival as an outcome, which is surprising, given that life expectancy is the most important outcome for patients with terminal illness.37 Additionally, QOL was also measured and reported in only 4 of the 10 studies; these studies used different QOL measures making comparisons more difficult. However, despite selective reporting in individual studies, these findings represent the totality of the currently available evidence. The overall methodological quality of included studies ranged from moderate to low, which can be attributed to lack of allocation concealment and blinding. Whether, the lack of allocation concealment is an artefact of reporting or conduct38 could not be determined since study protocols were not available. Regarding the lack of blinding, we believe this issue is not a major concern because survival was the main outcome for our study; mortality is an objective outcome and blinding is important in cases where the outcome is subjective.

In summary, our systematic review of available RCTs in patients with terminal illness shows that TTD compared with PC does not impact survival and is associated with increased toxicity. The results provide assurance to physicians, patients, and family that the patients with estimated survival of <6 months would be better off by referral to hospice. Whether new drugs with potentially life prolonging potential and safer toxicity profile will challenge these findings can only be determined in future well designed RCTs with adequate power. The average sample size in included studies was 124, which provides 15% power to detect a 15% survival difference (HR of 0.85 observed in this meta-analysis). To detect a 15% survival difference with 80% power and a 0.05 level of significance, a sample size of 1194 patients is needed. In the mean time, the physicians should be judicious in actively treating patients whose estimated survival is <6 months and provide information on benefits and risks associated with TTD versus PC to facilitate shared decision-making.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Ambuj Kumar @drambuj

Contributors: TR, AK and BD contributed to the study concept and design. TR, AK and FAK performed the data abstraction, analysis and interpretation. TR and AK participated in the drafting of the manuscript. TR, AK, FAK and BD performed the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. TR performed the statistical analysis. BD obtained funding. “TR and FAK were responsible for procurement of full text of all articles for data abstraction, printing of data abstraction forms and entering of data for analysis.” AK and BD were involved in the study supervision. TR, AK, FAK and BD approved final version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding: This work was supported by Department of Defense (grant number W81-XWH-09-2-0175) (PI: Djulbegovic).

Disclaimer: The funding agency did not play a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The researchers worked independently of the funding agency for this systematic review.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuyama R, Reddy S, Smith TJ. Why do patients choose chemotherapy near the end of life? A review of the perspective of those facing death from cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3490–6. 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temel JS, McCannon J, Greer JA et al. Aggressiveness of care in a prospective cohort of patients with advanced NSCLC. Cancer 2008;113:826–33. 10.1002/cncr.23620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braga S, Miranda A, Fonseca R, al The aggressiveness of cancer care in the last three months of life: a retrospective single centre analysis. Psychooncology 2007;16:863–8. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/pon.1140/asset/1140_ftp.pdf?v=1&t=if5nhyp4&s=d16669f8d895a9851c491006aac5ae0972502107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keam B, Oh DY, Lee SH et al. Aggressiveness of cancer-care near the end-of-life in Korea. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2008;38:381–6. http://jjco.oxfordjournals.org/content/38/5/381.full.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martoni AA, Tanneberger S, Mutri V. Cancer chemotherapy near the end of life: the time has come to set guidelines for its appropriate use. Tumori 2007;93:417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soh TI, Yuen YC, Teo C et al. Targeted therapy at the end of life in advanced cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2012;15:991–7. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonsalves WI, Tashi T, Krishnamurthy J et al. Effect of palliative care services on the aggressiveness of end-of-life care in the Veteran's Affairs cancer population. J Palliat Med 2011;14: 1231–5. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:315–21. 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emanuel EJ, Young-Xu Y, Levinsky NG et al. Chemotherapy use among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:639–43. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellmunt J, Theodore C, Demkov T et al. Phase III trial of vinflunine plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone after a platinum-containing regimen in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4454–61. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmid EU, Alberts AS, Greeff F et al. The value of radiotherapy or chemotherapy after intubation for advanced esophageal carcinoma—a prospective randomized trial. Radiother Oncol 1993;28:27–30. 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90181-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cartei G, Cartei F, Cantone A et al. Cisplatin-cyclophosphamide-mitomycin combination chemotherapy with supportive care versus supportive care alone for treatment of metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:794–800. 10.1093/jnci/85.10.794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2000;320:469–72. 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glare P, Virik K, Jones M et al. A systematic review of physicians’ survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 2003;327:195–8. 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007;8:16 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selawry O, Krant M, Scotto J et al. Methotrexate compared with placebo in lung cancer. Cancer 1977;40:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Marinis F, Rinaldi M, Ardizzoni A et al. The role of vindesine and lonidamine in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized FONICAP trial. Italian Lung Cancer Task Force. Tumori 1999;85:177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranson M, Davidson N, Nicolson M et al. Randomized trial of paclitaxel plus supportive care versus supportive care for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1074–80. 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xinopoulos D, Dimitroulopoulos D, Karanikas I et al. Gemcitabine as palliative treatment in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer previously treated with placement of a covered metal stent. A randomized controlled trial. J BUON 2008;13:341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciuleanu TE, Pavlovsky AV, Bodoky G et al. A randomised phase III trial of glufosfamide compared with best supportive care in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma previously treated with gemcitabine. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1589–96. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lissoni P, Ardizzoia A, Meregalli S et al. A clinical-study of immunotherapy versus endocrine therapy versus chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep 1994;1:1277–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lissoni P, Barni S, Ardizzoia A et al. A randomized study with the pineal hormone melatonin versus supportive care alone in patients with brain metastases due to solid neoplasms. Cancer 1994;73:699–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Astrow AB, Popp B. The palliative care information act in real life. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1885–7. 10.1056/NEJMp1102392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB. Death, dying, and end of life. JAMA 2016;315:270–1. 10.1001/jama.2015.19102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron NB et al. Barriers to quality end-of-life care for patients with blood cancers. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3126–32. 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH, Ashcroft RE. Epistemologic inquiries in evidence-based medicine. Cancer Control 2009;16:158–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Connor NR, Hu R, Harris PS et al. Hospice admissions for cancer in the final days of life: independent predictors and implications for quality measures. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3184–9. 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen J, Pivodic L, Miccinesi G et al. International study of the place of death of people with cancer: a population-level comparison of 14 countries across 4 continents using death certificate data. Br J Cancer 2015;113:1397–404. 10.1038/bjc.2015.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Chang CH et al. Quality of end-of-life cancer care for Medicare beneficiaries: regional and hospital-specific analyses. In: Boronner KK, ed. Washington DC: The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Prectice, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith TJ, Girtman J, Riggins J. Why academic divisions of hematology/oncology are in trouble and some suggestions for resolution. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:260–4. 10.1200/jco.2001.19.1.260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greisinger AJ, Lorimor RJ, Aday LA et al. Terminally ill cancer patients. Their most important concerns. Cancer Pract 1997;5:147–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soares HP, Daniels S, Kumar A et al. Bad reporting does not mean bad methods for randomised trials: observational study of randomised controlled trials performed by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. BMJ 2004;328:22–4. 10.1136/bmj.328.7430.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014661supp_appendix.pdf (181.5KB, pdf)