Abstract

Objective

To assess associations of elevated lipid levels during gestation with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Methods

This prospective cohort study was conducted in a tertiary maternal hospital in Shanghai, China from February to November 2014. Lipid constituents, including triglycerides (TGs), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) of 1310 eligible women were assessed in the first (10–13+ weeks), second (22–28 weeks) and third (30–35 weeks) trimesters consecutively. Associations of lipid profiles with HDP and/or GDM outcomes were assessed.

Results

Compared with the normal group, maternal TG concentrations were higher in the HDP/GDM groups across the three trimesters (p<0.001); TC and LDL-c amounts were only higher in the first trimester for the HDP and GDM groups (p<0.05). HDL-c levels were similar in the three groups. Compared with intermediate TG levels (25–75th centile), higher TG amounts (>75th centile) were associated with increased risk of HDP/GDM in each trimester with aORs (95% CI) of 2.04 (1.41 to 2.95), 1.81 (1.25 to 2.63) and 1.78 (1.24 to 2.54), respectively. High TG elevation from the first to third trimesters (>75th centile) was associated with increased risk of HDP, with an aOR of 2.09 (1.16 to 3.78). High TG elevation before 28 weeks was associated with increased risk of GDM, with an aOR of 1.67 (1.10 to 2.54). TG elevation was positively correlated with weight gain during gestation (R=0.089, p=0.005).

Conclusions

Controlling weight gain during pregnancy could decrease TG elevation and reduce the risk of HDP/GDM. TGs could be used as follow-up parameters during complicated pregnancy, while other lipids are meaningful only in the first trimester.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was a large prospective longitudinal cohort study, and previous reports assessing lipid levels have cross-sectional or retrospective designs, which could not avoid individual bias with respect to lipid level increase during gestation.

Lipid elevation was assessed here for the first time throughout pregnancy (from the first to third trimesters) among the same women in a large-scale research.

Maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index, weight gain, fasting glucose levels, gestational age and fasting state are associated with lipid levels, and were adjusted in this study.

Diet control may affect lipid levels in the third trimester, which might result in biased interpretation in the gestational diabetes mellitus group.

No lipid profile before pregnancy was obtained, constituting a study limitation.

Introduction

Pregnancy is considered a ‘stress test’ for metabolic and cardiovascular conditions of the body.1 2 Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are associated with an elevated risk of developing subsequent systemic hypertension and type II diabetes, affecting the cardiovascular system.3 Hyperlipidaemia, specifically hypertriglyceridaemia, is a well-known risk factor for metabolic syndromes. Indeed, triglyceride levels are significantly elevated in women with GDM/HDP compared to those without these metabolic syndromes, and such elevations are consistent in the first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy.4 5 However, associations of total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) levels in these populations with GDM/HDP are inconsistent in available reports.

Hyperlipidaemia is common in the second half of pregnancy as a physiologically required mechanism to maintain stable fuel supplementation to the fetus. It is also common to observe modest lipid level increases early in pregnancy, but significant elevations later in pregnancy.6 However, whether elevated lipid concentrations during gestation are associated with the risk of GDM/HDP could not be clarified in previous cross-sectional and retrospective studies. Thus, it is difficult to ascertain which level of lipid elevation is physiological or pathological. In addition, whether intrapregnancy weight gain and dietary modifications are correlated with elevated lipid levels remain unknown.

This prospective longitudinal cohort study aimed to provide a comprehensive description of lipid profile changes based on gestational age during pregnancy. We sought to test the hypothesis that a higher increase of triglyceride (TG) levels during gestation is associated with pregnancy complications such as GDM and HDP. In addition, we explored a possible correlation between weight gain and lipid profile elevation during gestation.

Methods

Setting and participants

This prospective cohort study was conducted at International Peace Maternity and Child Healthcare Hospital (IPMCHH), one of the largest obstetric care centres in Shanghai, China, with an annual delivery volume over 15 000. Participants were recruited from February to November 2014. Longitudinal lipid assessments were carried out during three periods: 10–13+ GW (first prenatal visit), 22–28 GW (second trimester) and 30–35+ GW (third trimester). Women with pre-pregnancy cardiovascular disease, chronic hypertension, pre-pregnancy diabetes or twin pregnancy were excluded. A total of 1376 women agreed to participate in this study and provided signed informed consent.

Measurements

Blood samples were collected at the outpatient clinic by a trained nurse after a 10–12 hour fasting period. Serum TC, LDL-c, HDL-c, TG and glucose concentrations were measured on a Hitachi type 7180 automatic biochemical analyser (Japan, Hitachi High-Tech Science Systems Corporation) and monitored by a well-trained inspector. Intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation in this analysis were ≤5% and ≤10%, respectively. Maternal body weight (kg) was obtained on an electronic scale at every follow-up visit, with weight gain recorded. Pre-pregnancy weights were recorded at the first obstetric clinic (self-reported). Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) was derived as the weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (metres), and the patients were classified as low weight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) or obese (≥30.0 kg/m2). Gestational age was based on the combination of last menstrual period and first-trimester ultrasound.

Other maternal characteristics, including maternal age (years), education (years of schooling), gravidity, parity, medical history, reproductive and prenatal history, smoking status and alcohol use, were obtained at the first clinic visit. All participants were followed up to the postpartum period. Maternal weight, blood pressure and complications at each antenatal clinical visit were recorded. Labour and delivery records, as well as postpartum and neonatal information, were recorded according to criteria included in the standardised data collection form.

Operational definitions

IPMCHH used the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups’ one-step criteria for GDM diagnosis. The one-step approach with 75 g, 2 hours Oral Glucose Tolerance Test, was performed at 24–28 weeks of gestation. GDM was diagnosed when 1 or more glucose indexes met or exceeded the following cut-offs: fasting, ≥5.1 mmol/L; 1 hour, 10.0 mmol/L; 2 hour, 8.5 mmol/L. Women diagnosed with GDM received nutritional counselling and/or dietary therapy, along with insulin if required. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy included gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg systolic or 90 mm Hg diastolic on at least two occasions 4–6 hours apart, with or without proteinuria (300 mg protein or more in a 24 hour urine sample or+on a urine dipstick).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics included means and SDs for continuous variables, and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Group comparisons were performed by a χ2 test or analysis of variance as appropriate. Associations of low HDL-c, high TGs, TC, and LDL-c with GDM or HDP, as well as a primary composite outcome, were assessed by multivariable logistic regression for factors with statistical significance in univariate analysis. Data for each lipid test (TC, LDL-c, HDL-c and TG levels) in each pregnancy trimester were divided into three groups: ‘low level’ (<25th centile); ‘intermediate level’ (between 25th and 75th centiles) and ‘high level’ (>75th centile). ‘Intermediate level’ was selected as a reference. Variable selection in the multivariable model was based on clinical and statistical significance. Confounding variables included maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, education years, fasting glucose levels and gestational age at blood collection. Linear regression was used to assess the correlation between TG elevation and weight gain. SPSS V.19.0 (SPSS, USA) was used for all analyses. p Value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

From February to November 2014, a total of 1376 eligible women consented to participate in this study, and their lipid concentrations were tested at the first prenatal visit. During follow-up, 9 women had miscarriage or pregnancy termination for fetal structure abnormalities before the second trimester; 10 others delivered before the third trimester blood collection. After third trimester lipid assessment, 8 women delivered at <34 gestational weeks. Meanwhile, 39 women chose other hospitals for delivery, and were lost to follow-up. Therefore, 1310 women (95.2%) were included in the final analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population.

HDP were diagnosed in 60 of the 1310 women (4.58%) with 23 preeclampsia and 37 with gestational hypertension. Most cases were detected after 34 weeks of gestation. A total of 6 HDP cases were diagnosed before 34 gestational weeks, and good blood pressure control and term delivery were achieved. There was no significant difference in lipid levels between the preeclampsia and gestational hypertension groups (data not shown). Meanwhile, 137 women (10.46%) had GDM complications, including five cases who received insulin therapy. The HDP/GDM composite end point occurred in 188 women (14.35%). All women were of Han ethnicity, and none smoked or consumed alcohol during pregnancy (data not shown). Other maternal characteristics and neonatal outcomes of the study population are shown in table 1. Women complicated with the HDP/GDM composite outcome were older (30.56±3.47 vs 29.55±3.13, p<0.001) and heavier (pre-pregnancy BMI 22.07±2.93 vs 20.79±2.9, p<0.001), with higher fasting glucose levels at the first trimester (4.59±0.42 vs 4.45±0.36, p<0.001). In addition, the caesarean section rate (44.7% vs 34.0%, p=0.004) was higher and babies were delivered earlier in the HDP/GDM group (39.12±0.99 39.5±1.17, p<0.001).There were no differences between groups in gravidity, parity, blood collection timing in each trimester, neonatal gender, average birth weight, incidence of birth weight ≥4000 g and preterm birth rate.

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics and neonatal outcomes among patients with complications and control populations

| HDP/GDM (n=188) | NW (n=1122) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 30.56±3.47 | 29.55±3.13 | <0.001 |

| Educational levels (years) | 15.88±1.69 | 15.86±1.45 | 0.851 |

| Primiparous-n (%) | 168 (89.4%) | 1001 (89.2%) | 0.952 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI-n (%) | 22.07±2.93 | 20.79±2.9 | <0.001 |

| <18.5 (kg/m2) | 12 (6.4%) | 123 (11.0%) | <0.001 |

| 18.5–24.9 (kg/m2) | 149 (79.3%) | 938 (83.9%) | |

| 25.0–29.9 (kg/m2) | 24 (12.8%) | 56 (5.0%) | |

| ≥30.0 (kg/m2) | 3 (1.6%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Fasting glucose at blood test 1 (mmol/L) | 4.59±0.42 | 4.45±0.36 | <0.001 |

| GW at blood test 1 | 12.41±0.45 | 12.41±0.48 | 0.986 |

| GW at blood test 2 | 24.93±0.88 | 24.97±0.94 | 0.599 |

| GW at blood test 3 | 32.56±0.95 | 32.64±1 | 0.297 |

| Delivery gestation (GW) | 39.12±0.99 | 39.5±1.17 | <0.001 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3351.25±412.74 | 3350.03±412.74 | 0.970 |

| Placenta weight (g) | 647.63±216.19 | 643.91±198.78 | 0.815 |

| Caesarean section-n (%) | 84 (44.7%) | 381 (34.0%) | 0.004 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 87 (46.3%) | 582 (51.9%) | 0.156 |

| Preterm delivery (34–37 weeks) | 4 (2.1%) | 28 (2.5%) | 0.762 |

| Birth weight ≥4000 g, n (%) | 13 (6.9%) | 75 (6.7%) | 0.907 |

BMI, body mass index; GW, gestational week; HDP/GDM, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP)/gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM); NW, normal women.

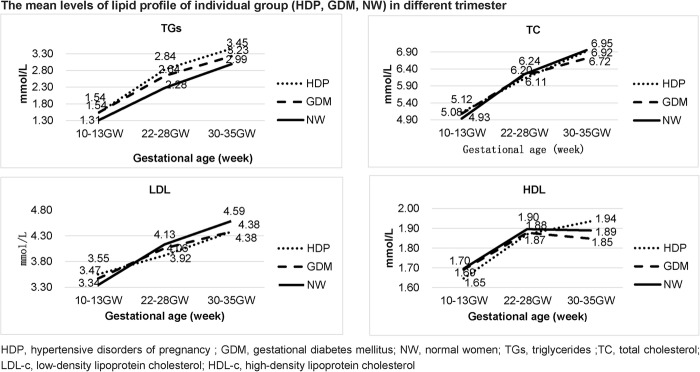

Lipid (TG, TC, LDL-c and HDL-c) profiles in the three groups (HDP, GDM and normal women (NW)) in different trimesters are depicted in figure 2. In the NW group, TG, TC and LDL-c concentrations increased progressively throughout pregnancy; meanwhile, HDL-c amounts increased from the first to second trimester with a slight decrease in the third trimester. Compared with the normal women group, the HDP and GDM groups showed higher TG concentrations throughout pregnancy, while TC and LDL-c concentrations were higher at the first clinical visit, but lower in the second and third trimesters. No statistically significant difference was observed in HDL-c levels among the three groups (figure 2).

Figure 2.

The mean levels of lipid profile of individual group (HDP, GDM, NW) in different trimester. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; NW, normal women.

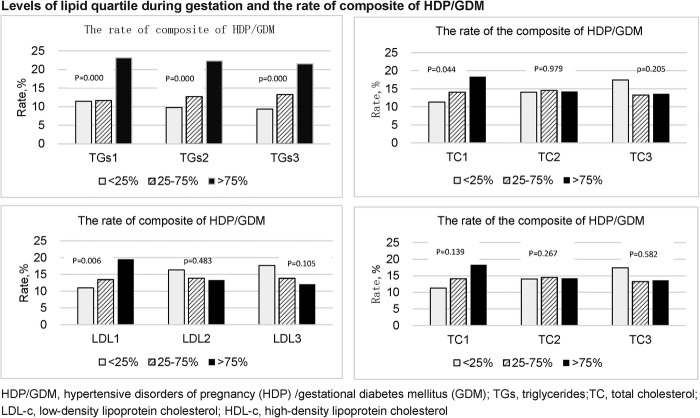

In the 4th quartile TG level group (>75th centile), the rate of composite end point (HDP/GDM) increased to 23.15%, from 11.48% in the1st quartile TG group (<25th centile) at the first lipid assessment. Similar results were obtained in the second (9.79% vs 22.29%) and third (9.37% vs 21.56%) trimesters (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Levels of lipid quartile during gestation and the rate of composite of HDP/GDM. HDP/GDM, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP)/gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

HDP/GDM prevalence increased with TC levels, from 11.29% in the 1st quartile TC group to 18.31% (p=0.044) in the 4th quartile TC group at the first clinical visit. Such a trend was not found in the second and third trimesters. Similar results were found for LDL-c. The incidence of composite HDP/GDM increased with LDL-c levels in early pregnancy, from 10.97% in the 1st quartile level group to 19.50% in the 4th quartile level group (p=0.006). Such a trend was not found in the second and third trimesters (figure 3).

Associations of lipid profile with HDP and GDM

Compared with the intermediate TG levels, the 4th quartile TG levels throughout pregnancy were associated with increased risks of combined HDP and GDM with aORs (95% CI) of 2.04 (1.41 to 2.95), 1.81 (1.25 to 2.63) and 1.78 (1.24 to 2.54), respectively, in the first, second and third trimesters. The 4th quartile levels of TGs throughout pregnancy were also a risk factor for the individual outcome of HDP with aORs (95% CI) of 1.94 (1.05 to 3.59), 1.83 (1.02 to 3.27) and 2.89 (1.72 to 4.84), respectively, in the first, second and third trimesters (table 2). Interestingly, TG elevation from the first to third trimesters was associated with increased risks of combined HDP/GDM (aOR=1.58, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.28, p=0.015) as well as HDP (aOR=2.09, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.78, p=0.015). The 4th quartile levels of TGs were associated with increased risks of GDM with aORs (95% CI) of 2.09 (1.37 to 3.17) and 1.93 (1.25 to 2.98) in the first and second trimesters, respectively. However, an elevated TG level in the third trimester was not a risk factor for GDM (aOR=1.51, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.28, p=0.54). Meanwhile, TG elevation from the first to second trimester was associated with increased risk of GDM (aOR=1.67, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.54, p=0.017).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis predicting HDP and/or GDM

| HDP |

GDM |

Composite of HDP/GDM |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| 4th quartile TGs at 1st trimester | 2.35 (1.30 to 4.23) | 1.94 (1.05 to 3.59)* | 2.21 (1.48 to 3.29) | 2.09 (1.37 to 3.17) | 2.28 (1.60 to 3.25) | 2.04 (1.41 to 2.95)* |

| 4th quartile TGs at 2nd trimester | 1.97 (1.12 to 3.45)* | 1.83 (1.02 to 3.27)* | 2.05 (1.38 to 3.04)* | 1.93 (1.25 to 2.98) * | 1.97 (1.39 to 2.79)* | 1.81 (1.25 to 2.63)* |

| 4th quartile TGs at 3rd trimester | 2.28 (1.32 to 3.94)* | 2.89 (1.72 to 4.84)* | 1.63 (1.09 to 2.44)* | 1.51 (0.99 to 2.28)* | 1.80 (1.27 to 2.54)* | 1.78 (1.24 to 2.54)* |

| Higher (4th quartile) TGs elevation† | 1.88 (1.06 to 3.33)* | 2.09 (1.16 to 3.78)* | 1.24 (0.82 to 1.89) | 1.26 (0.83 to 1.94) | 1.49 (1.04 to 2.13)* | 1.58 (1.09 to 2.28)* |

| 4th quartile TC at 1st trimester | 1.77 (0.97 to 3.26) | 1.69 (0.91 to 3.13) | 1.10 (0.72 to 1.68) | 1.15 (0.75 to 1.78) | 1.37 (0.95 to 1.97) | 1.38 (0.95 to 2.01) |

| 4th quartile LDL at 1st trimester | 1.72 (0.95 to 3.10) | 1.48 (0.80 to 2.71) | 1.43 (0.96 to 2.14) | 1.41 (0.93 to 2.15) | 1.56 (1.09 to 2.12)* | 1.46 (1.01 to 2.10)* |

Adjusted confounding variables included maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, education years, fasting glucose levels and gestational age at blood collection.

*p<0.05.

‡Adjusted before mentioned variables plus weight gain during gestation.

BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TGs, triglycerides.

With respect to other lipid profiles, the 4th quartile levels of LDL-c in the first trimester were associated with increased risk of combined HDP and GDM (aOR=1.46, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.10, p=0.044). Meanwhile, elevated TC in the first trimester was not a risk factor for the composite HDP/GDM outcome (aOR=1.38, 95% CI 0.95 to 2.01, p=0.91) (table 2).

Linear regression analysis showed that TG elevation was positively correlated with weight gain during gestation after adjusting for pre-pregnancy BMI (R=0.089, p=0.005). Weight gain from the first to third trimesters in the GDM group was significantly lower than that in the non-GDM group (7.80±3.22 kg vs 9.32±3.00 kg, p<0.001).

Discussion

Main findings

This study yielded three main findings: (1) First, high levels of TGs during pregnancy were associated with increased risk of HDP and GDM; in addition, TG elevation throughout gestation also conferred increased risk of combined HDP and GDM. (2) Then high LDL-c amounts were associated with increased risk of composite HDP/GDM in the first trimester; no significant difference was observed in HDL-c levels among the three groups. (3) Finally, TG elevation was positively correlated with weight gain during gestation.

Maternal fat depots occurring during the first two trimesters of gestation are associated with both hyperphagia and increased lipogenesis. Elevated insulin levels or even enhanced insulin sensitivity in early pregnancy and increased activity of adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase (LPL) contribute to lipogenesis and hyperlipidaemia. In late pregnancy, there is an accelerated breakdown of fat depots to meet maximal fetal growth requirements, with significant elevation of lipids later in pregnancy.6 Decreased insulin sensitivity (regulated by human placental lactogen, cortisol and sex steroids), reduced adipose tissue LPL sensitivity, increased activity of hormone-sensitive lipase and enhanced amounts of free fatty acids in circulation are associated with hyperlipidaemia in late pregnancy.7–9 Our findings that the levels of lipids, including TGs, TC and LDL, increased gradually during gestation and peaked before delivery are consistent with other studies.10 11 This elevation of lipid amounts is a physiological requirement for maintaining stable fuel supplementation to the fetus.

Both HDP and GDM are metabolic dysfunction disorders during pregnancy, and have the characteristics of insulin resistance.12 13 TG, TC and LDL concentrations were higher in the HDP/GDM group in the first trimester as shown above. These findings suggested that lipids in early gestational age show a more maternal metabolic condition than the physiological requirement for fetal growth. We found that maternal TG concentrations were higher in the HDP group across the three pregnancy trimesters, with elevated TG levels associated with HDP. These findings are consistent with a recent study by Ray et al4 demonstrating that elevated serum levels of TGs are associated with the risk of developing pregnancy-associated hypertension. The association between dyslipidaemia and the risk of preeclampsia is biologically plausible and compatible with the current knowledge of preeclampsia pathophysiology. GDM is associated with an elevated risk of developing subsequent type II diabetes. Patients with GDM showed higher TG amounts during pregnancy. Despite an ongoing debate regarding insulin resistance status in GDM, the association found between GDM and high TG levels in the present and other studies support the insulin resistance theory.5 14

The associations of elevated concentrations of lipids (specifically TGs) during gestation with the risk of GDM/HDP could not be clarified in cross-sectional and retrospective studies, making it difficult to ascertain which level of lipid elevation is physiological or pathological.15–17 As shown above, high TG elevation from the first to third trimesters was associated with HDP, which could be explained as follows. First, too much and too fast plasma lipid elevation may induce endothelial dysfunction secondary to oxidative stress.18 19 A second possible mechanism is the pathological process of preeclampsia via dysregulation of lipoprotein lipase, resulting in a dyslipidaemic lipid profile.20

A third possible mechanism may be via the metabolic characteristics of the ‘insulin resistance syndrome’, namely hyperinsulinemia.21 The association of elevated TG levels with GDM should be interpreted with caution in this study. Since interventions, including nutritional counselling and/or dietary therapy alongside insulin if required, could change the natural process of insulin resistance in this subgroup, we only found that stark TG elevation before intervention was associated with increased risk of GDM prevalence.

It is well known that weight gain during gestation is associated with pregnancy outcomes. Thus, IOM proposed a certain range of weight gain for women with a different pre-pregnancy BMI category.22 However, it remains unknown whether weight gain is correlated with lipid level changes during gestation. As shown above, TG elevation was positively correlated with weight gain after adjusting for pre-pregnancy BMI. This finding has clinical implications. Through dietary modifications and maternal weight control during pregnancy, TG level elevation could be reduced and HDP prevalence could be lowered in the high-level TG group. Qiu et al23 found that high dietary fibres can decrease TG concentration and reduce preeclampsia risk.

Strengths and limitations

This was a large prospective longitudinal cohort study, with the same women assessed from early pregnancy to delivery. Lipid levels were assessed in the first, second and third trimesters, as well as elevations during gestation. Although several meta-analyses have been published in this field, few studies examined lipids at multiple points during pregnancy.5 This study allows an understanding of the relationship between lipid levels during pregnancy and the development of hypertension and GDM. Maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain, fasting glucose levels, gestational age and fasting state are associated with lipid levels, and were adjusted in this study. An important limitation of this study is that all women with GDM received dietary guidance once diagnosis was established. Diet control may affect the third trimester lipid levels in the GDM group. In addition, we did not assess lipid profiles before pregnancy; thus, whether maternal weight control before pregnancy is associated with subsequent lipid levels and pregnancy outcomes remains unclear. Finally, the obesity rate was low in the study population, making it impossible to analyse the associations of lipid levels with HDP/GDM in this specific subgroup; this limits the generalisation of our findings to other populations with much higher rates of obesity.

Conclusion

Overall, in a large prospective longitudinal cohort study, we found that both hypertriglyceridaemia and highly elevated TG levels during gestation constitute risk factors for HDP/GDM. Maternal weight gain during pregnancy was positively correlated with TG level elevation. Controlling weight gain in pregnancy could decrease TG elevation and reduce the risk of HDP/GDM. TGs could be used as a follow-up index in complicated pregnancy, while the levels of other lipids are meaningful only in the first trimester.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cheng Lei, the information engineer of IPMCHH, for support in data collection. The authors would like to thank Yuan Long for carrying out biochemical tests, and the midwives in the labour and delivery rooms for detailed delivery records.

Footnotes

Contributors: WC designed the study. WC, HS and XL performed the experiments and analysed the data. YC and BH implemented the survey. All authors contributed to the data interpretation and writing of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (STCSM), grant number (134119a1100).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ethics review board of International Peace Maternity and Child Healthcare Hospital (number 201424).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Sattar N, Greer IA. Pregnancy complications and maternal cardiovascular risk: opportunities for intervention and screening? BMJ 2002;325:157–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartha JL, González-Bugatto F, Fernández-Macías R et al. Metabolic syndrome in normal and complicated pregnancies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;137:178–84. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermes W, Franx A, van Pampus MG et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in women who had hypertensive disorders late in pregnancy: a cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208:474.e1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray JG, Diamond P, Singh G et al. Brief overview of maternal triglycerides as a risk factor for pre-eclampsia. BJOG 2006;113:379–86. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00889.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryckman KK, Spracklen CN, Smith CJ et al. Maternal lipid levels during pregnancy and gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2015;122:643–51. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrera E, Ortega-Senovilla H. Maternal lipid metabolism during normal pregnancy and its implications to fetal development. Clinical Lipidology 2010;5:899–911. doi:10.2217/clp.10.64 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaaja R. Lipid abnormalities in pre-eclampsia: implications for vascular health. Clin Lipidol 2011;6:71–8. doi:10.2217/clp.10.82 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan EA, Enns L. Role of gestational hormones in the induction of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1988;67:341–7. doi:10.1210/jcem-67-2-341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams C, Coltart TM. Adipose tissue metabolism in pregnancy: the lipolytic effect of human placental lactogen. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1978;85:43–6. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1978.tb15824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farias DR, Franco-Sena AB, Vilela A et al. Lipid changes throughout pregnancy according to pre-pregnancy BMI: results from a prospective cohort. BJOG 2016;123:570–8. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vahratian A, Misra VK, Trudeau S et al. Prepregnancy body mass index and gestational age-dependent changes in lipid levels during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:107–13. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e45d23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaaja R, Tikkanen MJ, Viinikka L et al. Serum lipoproteins, insulin, and urinary prostanoid metabolites in normal and hypertensive pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 1995;85:353–6. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(94)00380-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barquiel B, Herranz L, Hillman N et al. Prepregnancy body mass index and prenatal fasting glucose are effective predictors of early postpartum metabolic syndrome in Spanish mothers with gestational diabetes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2014;12:457–63. doi:10.1089/met.2013.0153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sánchez-Vera I, Bonet B, Viana M et al. Changes in plasma lipids and increased low-density lipoprotein susceptibility to oxidation in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes: consequences of obesity. Metabolism 2007;56:1527–33. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2007.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enquobahrie DA, Williams MA, Butler CL et al. Maternal plasma lipid concentrations in early pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens 2004;17:574–81. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.03.666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lima VJ, Andrade CR, Ruschi GE et al. P49 serum lipid levels in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Sao Paulo Med J 2011;129:73–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashinakunti SV. Lipid profile in preeclampsia—a case–control study. J Clin Diagn Res 2010;4:2748–51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sattar N, Bendomir A, Berry C et al. Lipoprotein subfraction concentrations in preeclampsia: pathogenic parallels to atherosclerosis. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89:403–8. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00514-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sattar N, Gaw A, Packard CJ et al. Potential pathogenic roles of aberrant lipoprotein and fatty acid metabolism in preeclampsia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:614–20. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09827.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C, Austin MA, Edwards KL et al. Functional variants of the lipoprotein lipase gene and the risk of preeclampsia among non-Hispanic Caucasian women. Clin Genet 2006;69:33–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaaja R, Laivuori H, Laakso M et al. Evidence of a state of increased insulin resistance in preeclampsia. Metabolism 1999;48:892–6. doi:10.1016/S0026-0495(99)90225-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 548: weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:210–12. doi:http://10.1097/01.AOG.0000425668.87506.4c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu C, Coughlin KB, Frederick IO et al. Dietary fiber intake in early pregnancy and risk of subsequent preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens 2008;21:903–9. doi:10.1038/ajh.2008.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]