Abstract

Objectives

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) support the translation of research evidence into clinical practice. Key health questions in CPGs ensure that recommendations will be applicable to the clinical context in which the guideline is used. The objectives of this study were to identify CPGs for the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia; assess the quality of these guidelines using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument; and compare recommendations in relation to the key health questions that are relevant to the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia.

Methods

A multidisciplinary group identified key health questions that are relevant to the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia. The MEDLINE and EMBASE databases, websites of professional organisations and international guideline repositories, were searched for CPGs that met the inclusion criteria. The AGREE II instrument was applied by three raters and data were extracted from the guidelines in relation to the key health questions.

Results

In total, 3299 records were screened. 10 guidelines met the inclusion criteria. 3 guidelines scored well across all domains. Recommendations varied in specificity. Side effect concerns, rather than comparative efficacy benefits, were a key consideration in antipsychotic choice. Antipsychotic medication is recommended for maintenance of remission following a first episode of schizophrenia but there is a paucity of evidence to guide duration of treatment. Clozapine is universally regarded as the medication of choice for treatment resistance. There is less evidence to guide care for those who do not respond to clozapine.

Conclusions

An individual's experience of using antipsychotic medication for the initial treatment of first-episode schizophrenia may have implications for future engagement, adherence and outcome. While guidelines of good quality exist to assist in medicines optimisation, the evidence base required to answer key health questions relevant to the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia is limited.

Keywords: psychosis, antipsychotic

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to assess the quality of guidelines applicable to the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia.

A multidisciplinary group identified key health questions that informed a clinically focused, systematic approach to data extraction to enhance the relevance for medicines optimisation.

Robust application of a validated tool (AGREE II) to assess the quality of clinical practice guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia.

A limitation of the study is that only guidelines written in English were included.

The application of the AGREE II instrument reflects the quality of guideline reporting which may not always indicate all information about how the guideline was developed.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a complex mental illness that has a significant impact on the individual and their families. The lifetime risk of schizophrenia is ∼1% and typically manifests in early adulthood.1 The disorder is characterised by positive symptoms (such as delusions, hallucinations and disorganised speech), negative symptoms (such as social withdrawal and reduced motivation) and cognitive impairment.2 Approximately three-quarters of people who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia will experience a relapse with about one-fifth going on to have long-term symptoms and disability.1 3 The life expectancy of people with schizophrenia is reduced by 15–20 years compared to those without severe mental ill health, only 8% are in employment and the cost to society in England is estimated at £11.8 billion per year.4

In recent years, there has been an increasing emphasis on early intervention for people experiencing psychotic symptoms and on the reduction of the duration of untreated psychosis.5 Comprehensive programmes for the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia aim to promote recovery and improve quality of life and functional outcomes.6 Antipsychotic medication is a key component of the treatment offered, but the clinical use of these medicines differs in the management of first-episode schizophrenia in comparison to a relapse or recurrence of an established illness.7 At first presentation, a positive experience of using medication is likely to have long-term implications for adherence and outcome.8

Medicines optimisation is described by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as a person-centred approach to safe and effective medicines use, to ensure that people obtain the best possible outcomes from their medicines.9 To promote medicines optimisation, we must ensure that an individualised, evidence informed choice of medication is made available to service users.9 Translating the best available evidence into practice is a challenge, so clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are a useful summary of the most recent thinking in an area of clinical medicine. The Institute of Medicine describes CPGs as “statements that include recommendations intended to optimise patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options”.10 Guidelines and algorithms in mental healthcare can improve the quality of the services offered and the safety of medication use.11 12 Key health questions are used in guideline development processes to clarify the scope and purpose of the individual guideline.13 14 The definition of a set of clear and focused health questions will ensure that the recommendations are applicable to the clinical context in which the guideline is intended to be used.14

The quality of guidelines will have an impact on their applicability. The AGREE II tool has been used as a way of assessing the quality of guideline reporting in healthcare.15–18 A systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia was carried out by Gaebel et al15 in 2005. At this time, Gaebel et al did not include the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia when comparing the guidelines. Gaebel et al16 updated this work in 2011 by reviewing the most recent versions of CPGs that were considered to be of good quality in 2005. Differences in treatment recommendations have been evaluated by various authors in relation to guidelines that apply to the USA,19 or the difference in recommendations for single aspects of care such as maintenance treatment.20 Since guidelines are updated or new guidelines become available, it is important to continue to assess their quality and understand how the growing evidence base has influenced recommendations.

The aim of this paper is to review the quality of CPGs and compare guideline recommendations to inform practice in the field of first-episode schizophrenia. We sought to do this by adopting a systematic approach to retrieving relevant guidelines; using AGREE II to assess the quality of guidelines; developing a list of key health questions relevant to the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia and comparing guideline recommendations in relation to the key health questions identified.

Methodology

Data sources and search strategy

The PubMed and EMBASE databases were searched for guidelines relating to the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia (search terms described in online supplementary material appendix 1). A number of guideline repositories and specialist websites were searched for relevant guidelines. A manual search of reference lists for all identified guidelines was conducted. The initial search was conducted for guidelines published between January 2009 and April 2016.

bmjopen-2016-013881supp_appendix1.pdf (318KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Guidelines were included if they contained recommendations about the pharmacological treatment of adults experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia. A multidisciplinary group, compromised of consultant psychiatrists, pharmacists and nurses, with expertise in the care of people experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia, identified key clinical questions that a clinician would consider when taking an algorithmic approach to the use of medication for adults presenting with a first episode of schizophrenia (box 1). These key questions then informed the selection of guidelines to be included in the analysis.

Box 1. Key health questions in an algorithmic approach to the pharmacological treatment of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia in adults presenting to an early intervention for psychosis service.

Initial presentation

Which antipsychotic medications should be offered for the initial management of positive symptoms associated with a first episode of schizophrenia?

What is the recommended dose of antipsychotic medications for first-episode schizophrenia?

What is the duration of an initial trial of an antipsychotic for people experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia?

Which antipsychotic medication should be considered when the person has not responded to the initial antipsychotic trialled?

How long should a second antipsychotic trial last following non-response to the initial antipsychotic medication?

Is there a role for long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications or depot antipsychotic formulations in the management of first-episode schizophrenia?

When are combinations of antipsychotic medication an appropriate treatment strategy for people experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia?

Maintenance of remission

Which antipsychotic medication is recommended for the maintenance of remission from positive symptoms following a first episode of schizophrenia?

What is the dose of maintenance antipsychotic medication following a first episode of psychosis?

What is the duration of maintenance treatment following a first episode of schizophrenia?

Can targeted intermittent treatment with antipsychotic medication be recommended in the management of first-episode schizophrenia?

Treatment resistance

When should clozapine be considered in the pharmacological management of first-episode schizophrenia?

What is the recommended dose of clozapine?

What is the recommended duration of a clozapine trial to adequately assess response?

What strategies can be recommended for people who have had an inadequate response to clozapine treatment?

Guidelines were included if they were written in English, and made treatment recommendations based on a systematic review of the evidence in relation to adults aged 18 years or older. One reviewer (DK) did an initial screen of titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible records. Two reviewers (DK and SMcW) then completed the second screen of abstracts to identify records that would undergo a full review. Where more than one record related to a single guideline development process, they were considered together.

Assessment of guideline quality

The AGREE II instrument contains 23 items grouped into 6 domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity and presentation, applicability and editorial independence.13 The items are rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Domain scores are then scaled between 0% and 100%. Following completion of the online AGREE II tutorial and practice exercise,21 three reviewers (DK, SMcW, IS) independently applied the AGREE II criteria to each guideline. Domain scores were calculated based on the sum of all ratings within the domain and scaled by including the minimum possible score and the difference between the maximum and minimum possible scores for that domain.21 The AGREE II score calculator from McMaster University was used to calculate the domain scores and assess inter-rater reliability.22 A low level of discrepancy between raters (<1.5 SDs from the mean domain score) was found for each of the six domains within each guideline. The raters used the domain scores to judge overall acceptability of the guidelines for the purpose of informing the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia.

Comparison of guideline recommendations

Data in relation to guideline recommendations for the key health questions (box 1) were extracted by one reviewer (DK) and then a second reviewer (CH) checked the accuracy of this work.

Results

Search and selection of guidelines

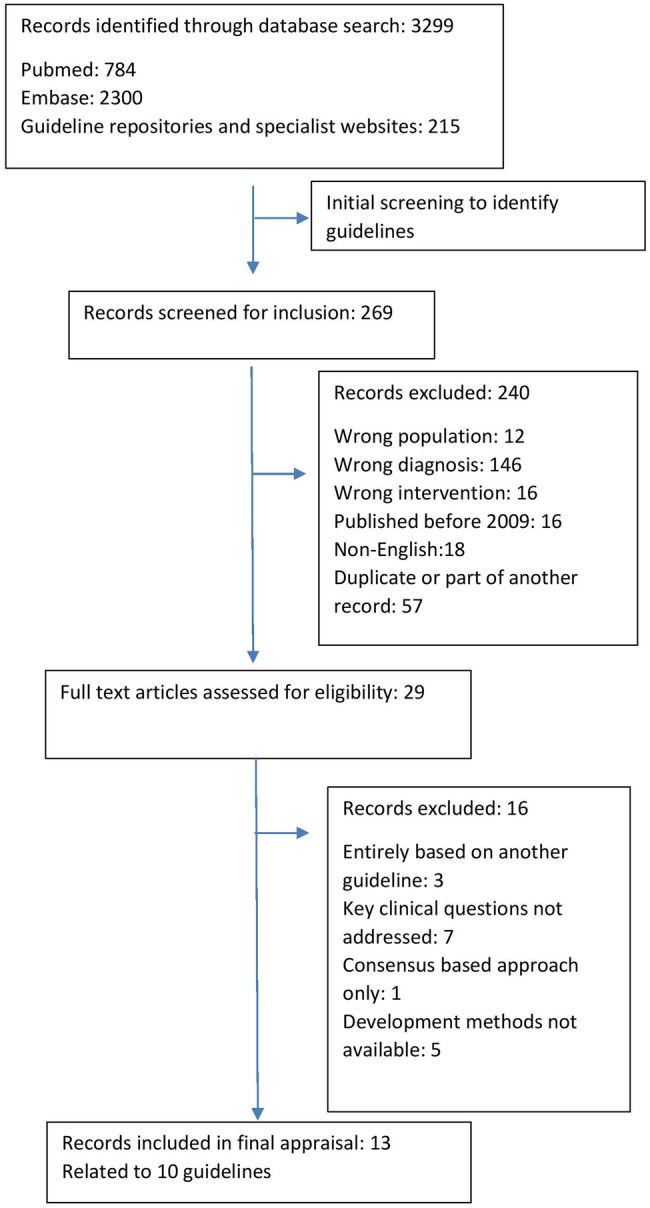

The search strategy identified a total of 3299 records which were screened and yielded a final number of 10 guidelines for inclusion in the analysis (figure 1). The guidelines and their general characteristics are listed in table 1. The guideline from the World Journal for the Society of Biological Psychiatrists (WFSBP) is published in three parts but considered as one guideline.23–25 The Royal Australia and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) guideline26 cross-references an Australian guide for the medical management of early psychosis,27 and they are therefore considered together. The reasons for excluding guidelines included lack of documented development methodology, language other than English, that the guideline was entirely based on another guideline or that it did not address the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram describing process of guideline selection.

Table 1.

General characteristics of guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia

| Title | Author/institution | Country | Publication date | End of search date* | Abbreviation and reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The 2009 Schizophrenia PORT Psychopharmacological Treatment Recommendations and Summary Statements | Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team | USA | December 2009 | March 2008 | PORT28 |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines for Schizophrenia and Incipient Psychotic Disorder | Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs | Spain | March 2009 | July 2007 | Spain29 |

| Management of Schizophrenia in Adults | Ministry of Health, Malaysia | Malaysia | May 2009 | Not described | Malaysia30 |

| Schizophrenia Clinical Practice Guidelines | Ministry of Health, Singapore | Singapore | April 2011 | Not described | Singapore31 |

| Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Clinical Psychopharmacology | British Association for Clinical Psychopharmacology | UK | 2011 | September 2008 | BAP32 |

| World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia | World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) | International | May 2012 to March 2015 | March 2012 | WFSBP23–25 |

| Management of Schizophrenia | Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network | Scotland | March 2013 | December 2011 | SIGN3 |

| The Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on schizophrenia | Harvard Medical School | USA | January 2013 | Not described. Paper submitted for publication December 2011 | Harvard33 |

| Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | UK | February 2014 | December 2008 (for pharmacologicalal treatment) | NICE34 |

| Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders | Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists | Australia and New Zealand | 2014 and 2016 | Not described | RANZCP26 27 |

*Final search date of the systematic review of evidence that informed the guideline development process.

Assessment of guideline quality

The standardised domain scores for each CPG are detailed in table 2. The domain scores for ‘scope and purpose’ were generally high with all but one guideline,33 scoring >80% (range 50–100%). There was wider variation among domain scores for stakeholder involvement, ranging from 20% to 90%. The reporting of development methodology as assessed by the ‘rigor of development’ domain was of variable quality with a range of 41% to 91%. In the domain ‘clarity of presentation’, CPGs generally scored well (range 52% to 96%) in contrast to the ‘applicability’ domain which had wide variability (14% to 79%). The reporting of ‘editorial independence’ in CPGs was scored between 25% and 97%. The guidelines selected were generally of good quality with three guidelines recommended for use as written, six guidelines acceptable with modifications and one not recommended. All reviewers were in agreement with the overall guideline acceptability.

Table 2.

Domain scores for CPGs addressing the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia using AGREE II as assessed by three raters and scaled as a percentage of the maximum possible score for each domain

| Domain | PORT (%) | Spain (%) | Malaysia (%) | Singapore (%) | BAP (%) | WFSBP (%) | SIGN (%) | Harvard (%) | NICE (%) | RANZCP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope and purpose | 85 | 85 | 100 | 96 | 93 | 83 | 96 | 50 | 100 | 81 |

| Stakeholder involvement | 54 | 80 | 93 | 75 | 63 | 44 | 90 | 20 | 89 | 67 |

| Rigour of development | 69 | 82 | 74 | 41 | 56 | 61 | 91 | 57 | 84 | 49 |

| Clarity of presentation | 85 | 89 | 94 | 94 | 83 | 52 | 96 | 78 | 94 | 83 |

| Applicability | 29 | 57 | 39 | 40 | 38 | 21 | 79 | 14 | 75 | 31 |

| Editorial independence | 78 | 75 | 97 | 25 | 39 | 64 | 78 | 86 | 86 | 42 |

| Overall assessment | Y | Y | Y/M | N | Y/M | Y/M | Y | Y/M | Y | Y/M |

N, guideline is not recommended; Y, guideline is recommended for use; Y/M, guideline is acceptable with modifications.

BAP, British Association of Psychopharmacology; CPG, clinical practice guidelines; NICE, National Institute of Clinical and Care Excellence; PORT, Patient Outcomes Research Team; RANCP, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; WFSBP, World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry.

Comparison of CPG content

Rating the quality of evidence used to support recommendations

Guideline development groups had a range of approaches to rating the quality of the evidence and grading the strength of related recommendations. The methodologies used are listed in the supplemental material (see online supplementary material, appendix 2). One CPG did not describe a method for grading evidence.33 PORT took a very direct approach of needing two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) as the minimum level of evidence required to make a recommendation.28 NICE requires the reader to understand the language used within the recommendations to interpret the strength of the recommendation.34 Other groups used methods of varying detail and complexity to describe the strength of evidence.3 23 26 29–32

bmjopen-2016-013881supp_appendix2.pdf (491.1KB, pdf)

Recommendations in relation to key health questions at initial presentation

A table comparing the recommendation from CPGs in relation to key health questions is available in online supplementary material appendix 3. Guidelines broadly agree that all antipsychotics are equally effective for the treatment of positive symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia.3 23 26 28–34 There is also a consensus that the most important consideration when helping a person make a decision about pharmacological treatment is the side effect profile of the antipsychotic.3 23 26 28–34 Five guidelines recommend second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) medications as the preferred initial choice because of the view that the side effect profiles of this group of medicines are more favourable.23 26 29 30 33 Olanzapine is specifically excluded as a recommended initial choice of antipsychotic medication from PORT,28 Harvard33 and RANZCP,26 because of the issue of metabolic side effects and weight gain. Harvard uses the additional consideration of efficacy in the maintenance phase of treatment in excluding quetiapine because of a poorer evidence base for maintenance of remission.33 All guideline development groups consider the evidence for the use of antipsychotic medications for first-episode schizophrenia to be of high quality even though not all antipsychotic medications have been tested in this cohort of patients. For example, WFSBP notes that haloperidol is the only first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) that has actually been used in trials in first-episode schizophrenia.23 Spain,29 and RANZCP,26 recommend an antipsychotic free assessment period using benzodiazepines to help alleviate distress.

bmjopen-2016-013881supp_appendix3.pdf (655.4KB, pdf)

The most common recommendation for the duration of an initial trial of antipsychotic medication is 4 weeks.29 31–34 Evidence that the majority of the benefit seen with antipsychotic medication will be apparent in the first two weeks of treatment is reflected in the potentially shorter trial period suggested by some guidelines.3 23 26 There is consensus regarding the lowest effective dose being used with a number of guidelines offering suggestions for FGA and SGA doses specific to the first episode of schizophrenia.23 26 28 33 The only exception to this dose recommendation is that of quetiapine, which requires a dose similar to that used in acute relapse based on the interpretation of the European First Episode Study35 trial by PORT.28

Oral medication is recommended with parenteral formulations reserved for those who prefer this route of administration or when poor adherence is a clinical priority.3 23 26 28–34 While monotherapy is ideal, there is recognition that combinations of antipsychotic medication may be useful in certain scenarios such as clozapine augmentation.3 23 26 28–34

Recommendations in relation to key health questions regarding the maintenance of remission following a first episode of schizophrenia

Recommendations regarding the duration of maintenance treatment following a first episode of schizophrenia vary between 1 and 2 years,3 24 26 29 30 34 with some guideline development groups failing to make any recommendation.28 31–33 RANZCP considers engagement with a first-episode schizophrenia service for up to 5 years to be beneficial.26 The antipsychotic medication used for relapse prevention is generally the antipsychotic used in the acute management of symptoms at the dose that was effective in the acute phase.3 24 28–31 33 Evidence for the superiority of medications such as olanzapine and risperidone, or inferiority of quetiapine in relapse prevention, is reflected in the recommendations of some guidelines.3 24 33 Targeted, intermittent treatment is a potential strategy that reduces side effect burden and the need for adherence to longer term medication use. The evidence, however, does not support this approach because of the increased risk of relapse in comparison to continuous treatment.24 28 32 34

Recommendations in relation to key health questions regarding treatment-resistant schizophrenia

There is consensus that the definition of treatment resistance is the failure of two trials of antipsychotic medication at optimal dose for an adequate period of time.3 23 26 28–34 Before making a diagnosis of treatment resistance, additional considerations include comorbid substance misuse and an assessment of treatment adherence. The interpretation of recent evidence regarding the efficacy of antipsychotic medication36 points to the trial of olanzapine, risperidone or amisulpride as one of the two antipsychotics used before a trial of clozapine is considered.3 33 Clozapine is universally recommended as the treatment of choice for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. The variation in doses suggested reflect the individuality of clozapine use in clinical practice,24 28 29 31–33 with the potential for delayed response to clozapine treatment leading to the longer duration of a trial of clozapine of up to 1 year recommended in some guidelines.26 28 29 32 The most common strategy suggested when there has been a partial response to clozapine despite dose optimisation is to combine clozapine with a second antipsychotic taking additional side effect profile and pharmacology into consideration.3 24 26 29–34 Lamotrigine is also considered by some CPGs to have sufficient evidence to recommend its use as a clozapine augmentation strategy.3 24 33 There is very little evidence to guide treatment options for those who do not have adequate symptom reduction despite clozapine augmentation.24 30 31 33

Discussion

Assessment of guideline quality

This systematic review identified 10 CPGs addressing the pharmacological management of first-episode schizophrenia which were assessed using the AGREE II instrument. The NICE, SIGN and Spanish guidelines scored best across all domains.3 29 34 The CPGs assessed were generally well presented with specific statements describing the scope and purpose of each guideline. The ‘rigor of development’ scores for each guideline reflected the quality of methodological reporting within the text of the guideline. Plans to update the guidelines were documented for six of the CPGs.3 28–31 34 Updates are currently due for two guidelines.29 30 The majority of recommendations regarding the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia in the NICE guidelines have not been updated since the 2009 version of the CPG.34 In most guidelines, there is significant cross-referencing of other similar guidelines.3 23 29–32 SIGN and Malaysia used the NICE evidence base as their foundation.3 30 This would appear reasonable as the NICE guideline was considered of very high quality in Gaebel et al's15 systematic review.

Guidelines were generally weakest in the applicability domain with little offered by way of support for implementation. Examples of tools used to support applicability included versions of the CPG for service users,3 29 34 algorithms26 29 33 34 and quality indicators.30 34 The inclusion of tools such as decision aids in guidelines may improve their applicability and make a collaborative approach to care more feasible in clinical practice.37 38 Overall assessment of quality was lowest for guidelines produced by specialist organisations, where limited stakeholder involvement added to poor applicability,23 32 33 or the reporting of development methodology was limited.23 26 33 Within the evidence base itself, publication bias is an important consideration.39 40 CPGs such as NICE and SIGN make significant efforts to measure the risk of bias in original trials.3 34 Response and remission are not well defined in the guidelines even though some recommend using rating scales to assess same.

Evidence-based recommendations are drawn up following an evaluation of available research and ranked according to the strength of the supporting evidence. Consensus-based recommendations are derived from the practical experience of the guideline developers. This methodology allows for the development of recommendations for clinical scenarios where the published evidence is weak or the evidence does not reflect the patient characteristics of everyday clinical practice.41 While the ‘rigor of development’ domain scores may be excellent in an AGREE assessment, the specificity of the subsequent recommendations vary. NICE emphasises that each treatment phase be considered an individual therapeutic trial and that this will encompass any new evidence that is published in relation to pharmacological approaches.34 In contrast, the WFSBP guideline evaluates the evidence in relation to each antipsychotic medication and Harvard makes more specific recommendations regarding the choice of antipsychotic medication.23 33 It is clear from the levels of evidence used to make recommendations in CPGs that the available research is not comprehensive enough to address all key health questions relevant to the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia. It is therefore reasonable to accept a transparent, consensus-based approach so that the reader can also take a view on the topic.

Clinical significance

Early intervention for those experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia has the potential to improve outcomes and is an important area of current research.42–45 Early intervention services provide a range of pharmacological, psychological and educational interventions with the aims of symptom remission and functional recovery with respect to personal, employment, educational and social outcomes.46 Antipsychotic medication is a key component of care.6 The clinical use of medication differs in this cohort of patients, who tend to be more sensitive to the effects of antipsychotic medication and more vulnerable to adverse effects than those in later phases of the illness.35 Specific guidelines that address the key health questions relevant to the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia are therefore required.

Navigating the varying side effect profiles of individual antipsychotic medicines has become the clinical priority when choosing the most appropriate medication in first-episode schizophrenia. Adverse effects have a significant impact on quality of life and adherence to medication,47 48 and this must be balanced against the fact that residual symptoms also have an impact on quality of life.49 Research among those experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia demonstrated the increased sensitivity to metabolic side effects of SGAs without greater efficacy when compared to FGAs.35 50 The risk of long-term neurological side effects such as tardive dyskinesia with FGAs has led to a consensus among some guideline development groups that SGAs are preferable in first-episode schizophrenia.23 26 29 30 33 Where FGAs are chosen, low potency FGAs such as chlorpromazine are preferred.3 23 32 Guidelines that relegate olanzapine to second-line treatment do so because of the relatively high risk of metabolic side effects and weight gain in particular.26 28 33 An antipsychotic free assessment period is recommended by two CPGs, presumably to allow for a clear picture of symptoms to be obtained at baseline.26 29 However, the feasibility of implementing this recommendation depends on ease of access to specialised assessments for first-episode schizophrenia and it may not be reasonable to delay treatment.

Approximately 20% of those who meet the diagnostic criteria for a first episode of schizophrenia will not go on to experience any subsequent episodes.1 The optimal duration of treatment following a first episode of schizophrenia is therefore an important health question. In one recent study, the relapse rate for those who discontinued medication following 18 months of treatment (and were in clinical remission for more than 12 months with 6 months or more of functional recovery) was twice that of those who continued maintenance antipsychotic medication over the 3-year study period.51 There is evidence of benefit for service users who remain in contact with an early intervention service for up to 5 years compared to those who do not.42 Wunderink et al52 have suggested shorter periods of antipsychotic use, arguing that despite reoccurrence of symptoms, quality of life at 7-year follow-up was better for those who had discontinued medication at 6 months than those who received maintenance antipsychotic medication. These findings have not been replicated and current practice supports maintenance treatment with informed choices to be made at an individual level regarding continuation of antipsychotic medication at ∼2 years following symptom remission of the first episode.53

Evaluations of the efficacy of antipsychotic medication have not demonstrated superiority for any individual agent for those experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia,34 with response rates between 40% and 90%.54 Clozapine, for example, is no more effective than chlorpromazine as initial treatment.55 Response rates to subsequent trials of antipsychotic medications other than clozapine are poor.56 Recent evidence suggests that there may be some efficacy benefit for individual SGAs in the acute phase of established recurrent schizophrenia36 and for maintenance of remission.57 This evidence has been interpreted in guidelines by suggesting that risperidone, olanzapine or amisulpride should be used as one of the two antipsychotics recommended before a trial of clozapine is considered.3 33 While oral medication is recommended in CPGs, there is increasing interest in the use of long-acting antipsychotic injections early in schizophrenia treatment because of the potential to detect non-adherence early, reduce relapse and improve psychosocial functioning.58

Clozapine is universally accepted by guideline development groups as the antipsychotic of choice for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Approximately 60% of those who are considered treatment-resistant will respond to clozapine.59 Leucht et al's36 analysis of the efficacy of antipsychotic medication in the acute phase of multiepisode schizophrenia showed the relative benefit of clozapine. The use of clozapine is supported by open label studies, cohort studies and database studies with important positive outcomes such as reduced hospitalisation.60–62 However, in a recent multivariate meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials comparing clozapine and other antipsychotic medication, the Cochrane Collaboration failed to find any significant efficacy difference in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.63 The authors highlighted the many limitations of RCTs in the area of treatment resistance including varying definitions of treatment resistance. Differing doses of antipsychotics and the difficulty of blinding to clozapine treatment. Given the benefits of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia and the importance of early effective treatment for those experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia, it has been argued that clozapine should be considered earlier in the treatment algorithm as a second-line option.54

CPGs are not intended to dictate all aspects of care for patients. Individual factors such as personal preferences, comorbidity, concurrent medications and previous experience with medication will have an impact on the choices made. Although guidelines and algorithms in mental healthcare can improve the quality of medication use,11 12 CPGs are not always used in practice64–66 and implementation strategies do not always result in improved adherence to guideline recommendations.67 In the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) study, the authors identified 39% of the sample who could have benefited from a medication review because prescribing practices were not in line with current guidelines in the USA.68 For example, the use of olanzapine was relatively high, even though it is specifically not recommended in a first episode of schizophrenia by the PORT guidelines. The UK National Audit of Schizophrenia examined the implementation of NICE guidelines. While most of the sample of 5608 patients were receiving pharmacological treatment in line with the guideline, 11% were prescribed two or more antipsychotic medications and 10% were prescribed doses above the recommended limits.69 Despite the importance placed on early use of clozapine in CPGs, evidence suggests it is under-prescribed with many different strategies being used before clozapine is offered.70 71 Clozapine's effectiveness may diminish if used later in the illness, making it vitally important to identify treatment resistance and manage it appropriately as early as possible.72 Within the setting of an early intervention service, it may be feasible to implement guidelines more effectively when they are relevant to those experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia, are facilitated by local buy-in and reflect a multidisciplinary approach.64

Strengths and limitations

The clinical use of antipsychotic medication as part of the early intervention model of service delivery is an important topic of current research. A strength of this study is the identification of key health questions that are relevant to clinical practice and the comparison of guideline recommendations in relation to these key health questions. The AGREE II tool has been extensively used to evaluate the quality of CPGs in many aspects of clinical care including psychiatry.15 17 18 Using the AGREE II tool helps to identify guidelines that have a transparent, systematic method of development. For services that are not bound by national guidelines, this work could inform the development of local guidelines using methodology such as the ADAPTE process.14

The AGREE II tool does not evaluate the quality of the evidence that was used to formulate the recommendations. The subjectivity inherent in the application of the AGREE II tool is reduced by the independent scoring of CPGs by three raters and by further measuring any marked discrepancy between scores. While every effort was made to include all relevant guidelines for the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia, it is possible that some have been inadvertently excluded. We only included guidelines written in the English language. Many of the guidelines included were published more than 5 years ago and could therefore be considered out of date.10 A comparison of CPG content would ideally involve taking the various methods by which quality of evidence is evaluated and grouping them into one standard method.14 The AGREE tool includes an assessment of bias in relation to statements of conflict of interest for those involved in guideline development and stakeholder involvement. Even if conflicts of interest were declared, it was difficult to ascertain how this was managed and how it influenced final recommendations.73 The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation working group has developed an Evidence to Decision framework for CPGs that has the potential to ensure a structured, transparent approach to developing CPG recommendations.74

Conclusions

The aims of early intervention for those experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia are to reduce symptoms and improve outcomes. Optimal use of antipsychotic medication is critical and clinical practice differs for the first-episode cohort in comparison to those experiencing multiepisode schizophrenia. CPGs can guide medicines optimisation, but it is important for the target users to assess the quality of CPGs so that they can have confidence in the recommendations made. The AGREE II instrument is a useful way of structuring this assessment. CPGs of good methodological quality for the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia exist but deficiencies in the evidence base make it difficult to address the key health questions relevant to medicines optimisation in clinical practice. Further research is required to guide choice and dose of medication, duration of treatment and the management of treatment resistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: DK developed the concept. DK, GC and SMcW contributed to the search for data. DK, SMcW and IS were involved in the application of the AGREE II tool. DK and CH participated in the extraction of data. JS and MC participated in a substantive review of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific financial support.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2016;388:86–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowen P, Harrison P, Burns T. Shorter Oxford textbook of psychiatry. Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of Schizophrenia. SIGN 131, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schizophrenia Commission. The abandoned illness: a report from the Schizophrenia Commission. London: Rethink Mental Illness, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGorry P, Bates T, Birchwood M. Designing youth mental health services for the 21st century: examples from Australia, Ireland and the UK. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202(54):s30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertolote J, McGorry P. Early intervention and recovery for young people with early psychosis: consensus statement. Br J Psychiatry 2005;187:s116–s19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Delman HM et al. Pharmacological treatments for first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2005;31:705–22. 10.1093/schbul/sbi032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert M, Conus P, Eide P et al. Impact of present and past antipsychotic side effects on attitude toward typical antipsychotic treatment and adherence. Eur Psychiatry 2004;19:415–22. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. NG 5. 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2016, http://www.nice.org.uk. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM et al. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. National Academies Press, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes TR, Paton C. Role of the prescribing observatory for mental health. Br J Psychiatry 2012;201:428–9. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paton C, Adroer R, Barnes TR. Monitoring lithium therapy: the impact of a quality improvement programme in the UK. Bipolar Disord 2013;15:865–75. 10.1111/bdi.12128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AGREE Next Steps Consortium. Appraisal of guidelines for research & evaluation II. AGREE II Instrument The AGREE Research Trust. 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2015, https://www.agreetrust.org. [Google Scholar]

- 14.ADAPTE Collaboration. The ADAPTE process: resource toolkit for guideline adaptation. Version 2.0. Retrieved 8 June 2015, http://www.g-i-n.net. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaebel W, Weinmann S, Sartorius N et al. Schizophrenia practice guidelines: international survey and comparison. Br J Psychiatry 2005;187:248–55. 10.1192/bjp.187.3.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaebel W, Riesbeck M, Wobrock T. Schizophrenia guidelines across the world: a selective review and comparison. Int Rev Psychiatry 2011;23:379–87. 10.3109/09540261.2011.606801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castellani A, Girlanda F, Barbui C. Rigour of development of clinical practice guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder: systematic review. J Affect Disord 2015;174:45–50. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazzano AN, Green E, Madison A et al. Assessment of the quality and content of national and international guidelines on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy using the AGREE II instrument. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009189 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore TA. Schizophrenia treatment guidelines in the United States. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 2011;5:40–9. 10.3371/CSRP.5.1.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeuchi H, Suzuki T, Uchida H et al. Antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia in the maintenance phase: a systematic review of the guidelines and algorithms. Schizophr Res 2012;134:219–25. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levinson AJ, Brouwers M, Durocher L, et al. AGREE II Tutorial and Practice Exercise. AGREE Enterprise. http://www.agreetrust.org/resource-centre/agree-ii-training-tools/

- 22.McMaster University. AGREE II rater concordance calculator 2008. http://fhswedge.csu.mcmaster.ca/cepftp/qasite/AGREEIIRaterConcordanceCalculator.html

- 23.Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry 2012;13:318–78. 10.3109/15622975.2012.696143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry 2013;14:2–44. 10.3109/15622975.2012.739708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia Part 3: Update 2015 Management of special circumstances: depression, suicidality, substance use disorders and pregnancy and lactation. World J Biol Psychiatry 2015;16:142–70. 10.3109/15622975.2015.1009163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2016;50:410–72. 10.1177/0004867416641195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ENSP Medical Management Writing Group. Medical management in early psychosis: a guide for medical practitioners. Orygen Youth Health Research Centre, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull 2010;36:71–93. 10.1093/schbul/sbp116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Working Group of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Schizophrenia and Incipient Psychotic Disorder. Mental Health Forum, coordination. Clinical practice guideline for schizophrenia and incipient psychotic disorder. Madrid: Quality Plan for the National Health System of the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs. Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research, 2009. Clinical Practice Guideline: CAHTA. Number 2006/05–2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Management of schizophrenia in adults. 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2015, http://www.acadmed.org.my. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministry of Health, Singapore. Schizophrenia Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2015, http://www.moh.gov.sg.

- 32.Barnes TR. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford) 2011;25:567–620. 10.1177/0269881110391123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osser DN, Roudsari MJ, Manschreck T. The psychopharmacology algorithm project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on schizophrenia. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2013;21:18–40. 10.1097/HRP.0b013e31827fd915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. CG178. 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2015, http://www.nice.org.uk. [PubMed]

- 35.Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2008;371:1085–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013;382:951–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel SR, Bakken S, Ruland C. Recent advances in shared decision making for mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2008;21:606 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32830eb6b4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ 2014;348:g3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med 2008;358:252–60. 10.1056/NEJMsa065779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mavridis D, Efthimiou O, Leucht S et al. Publication bias and small-study effects magnified effectiveness of antipsychotics but their relative ranking remained invariant. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:161–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samalin L, Guillaume S, Courtet P et al. Methodological differences between pharmacological treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder: what to do for the clinicians? Compr Psychiatry 2013;54:309–20. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norman RM, Manchanda R, Malla AK et al. Symptom and functional outcomes for a 5 year early intervention program for psychoses. Schizophr Res 2011;129:111–15. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Austin SF, Mors O, Secher RG et al. Predictors of recovery in first episode psychosis: the OPUS cohort at 10 year follow-up. Schizophr Res 2013;150:163–8. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill M, Crumlish N, Clarke M et al. Prospective relationship of duration of untreated psychosis to psychopathology and functional outcome over 12 years. Schizophr Res 2012;141:215–21. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gardsjord ES, Romm KL, Friis S et al. Subjective quality of life in first-episode psychosis. A ten year follow-up study. Schizophr Res 2016;172:23–8. 10.1016/j.schres.2016.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organisation, International Early Psychosis Association. An International Consensus Statement about Early Intervention and Recovery for Young People with Early Psychosis 2004. http://www.iris-initiative.org.uk/silo/files/early-psychosis-declaration.pdf

- 47.Dixon LB, Stroup TS. Medications for first-episode psychosis: making a good start. Am J Psychiatry 2015;172:209–11. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14111465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hynes C, Keating D, McWilliams S et al. Glasgow antipsychotic side-effects scale for clozapine—development and validation of a clozapine-specific side-effects scale. Schizophr Res 2015;168:505–13. 10.1016/j.schres.2015.07.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haro JM, Novick D, Perrin E et al. Symptomatic remission and patient quality of life in an observational study of schizophrenia: is there a relationship? Psychiatry Res 2014;220:163–9. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sikich L, Frazier JA, McClellan J et al. Double-blind comparison of first-and second-generation antipsychotics in early-onset schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder: findings from the treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS) study. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:1420–31. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mayoral-van Son J, de la Foz VOG, Martinez-Garcia O et al. Clinical outcome after antipsychotic treatment discontinuation in functionally recovered first-episode nonaffective psychosis individuals: a 3-year naturalistic follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry 2016;77:492–500. 10.4088/JCP.14m09540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wunderink L, Nieboer RM, Wiersma D et al. Recovery in remitted first-episode psychosis at 7 years of follow-up of an early dose reduction/discontinuation or maintenance treatment strategy: long-term follow-up of a 2-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry 2013;70:913–20. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karson C, Duffy RA, Eramo A et al. Long-term outcomes of antipsychotic treatment in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:57 10.2147/NDT.S96392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Remington G, Agid O, Foussias G et al. Clozapine's role in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia. Amer J Psychiatry 2013;170:146–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H et al. Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003;28:995–1010. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agid O, Arenovich T, Sajeev G et al. An algorithm-based approach to first-episode schizophrenia: response rates over 3 prospective antipsychotic trials with a retrospective data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:1439–44. 10.4088/JCP.09m05785yel [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Álvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2011;37:619–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heres S, Lambert M, Vauth R. Treatment of early episode in patients with schizophrenia: the role of long acting antipsychotics. Eur Psychiatry 2014;29 (Suppl 2):1409–13. 10.1016/S0924-9338(14)70001-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meltzer HY. Treatment of the neuroleptic-nonresponsive schizophrenic patient. Schizophr Bull 1992;18:515–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa051688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones PB, Barnes TR, Davies L et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect on Quality of Life of second-vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:1079–87. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stroup TS. What is the role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia? J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:1261–2. 10.4088/JCP.14com09518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Samara MT, Dold M, Gianatsi M et al. Efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of antipsychotics in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry 2016;73:199–210. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forsner T, Hansson J, Brommels M et al. Implementing clinical guidelines in psychiatry: a qualitative study of perceived facilitators and barriers. BMC psychiatry 2010;10:8 10.1186/1471-244X-10-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barbui C, Girlanda F, Ay E et al. Implementation of treatment guidelines for specialist mental health care. Schizophr Bull 2014;40:737–9. 10.1093/schbul/sbu065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Howes OD, Vergunst F, Gee S et al. Adherence to treatment guidelines in clinical practice: study of antipsychotic treatment prior to clozapine initiation. Br J Psychiatry 2012;201:481–5. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.105833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Girlanda F, Fiedler I, Becker T et al. The evidence–practice gap in specialist mental healthcare: systematic review and meta-analysis of guideline implementation studies. Br J Psychiatry 2016. 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.179093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robinson DG, Schooler NR, John M et al. Prescription practices in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: data from The National RAISE-ETP Study. Am J Psychiatry 2015;172:237–48. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Royal College of Psychiatrists. Report of the Second Round of the National Audit of Schizophrenia (NAS2) 2014. Health Care Quality Improvement Partnership, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taylor DM, Young C, Paton C. Prior antipsychotic prescribing in patients currently receiving clozapine: a case note review. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Üçok A, Çikrikçili U, Karabulut S et al. Delayed initiation of clozapine may be related to poor response in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;30:290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nielsen J, Nielsen RE, Correll CU. Predictors of clozapine response in patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia: results from a Danish Register Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;32:678–83. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318267b3cd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campsall P, Colizza K, Straus S et al. Financial relationships between organizations that produce clinical practice guidelines and the biomedical industry: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002029 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002029y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016;353:i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013881supp_appendix1.pdf (318KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013881supp_appendix2.pdf (491.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013881supp_appendix3.pdf (655.4KB, pdf)