Abstract

Introduction

There is no curative treatment available for patients with chemotherapy relapsed or refractory CD19+ B cells-derived acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (r/r B-ALL). Although CD19-targeting second-generation (2nd-G) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells carrying CD28 or 4-1BB domains have demonstrated potency in patients with advanced B-ALL, these 2 signalling domains endow CAR-T cells with different and complementary functional properties. Preclinical results have shown that third-generation (3rd-G) CAR-T cells combining 4-1BB and CD28 signalling domains have superior activation and proliferation capacity compared with 2nd-G CAR-T cells carrying CD28 domain. The aim of the current study is therefore to investigate the safety and efficacy of 3rd-G CAR-T cells in adults with r/r B-ALL.

Methods and analysis

This study is a phase I clinical trial for patients with r/r B-ALL to test the safety and preliminary efficacy of 3rd-G CAR-T cells. Before receiving lymphodepleting conditioning regimen, the peripheral blood mononuclear cells from eligible patients will be leukapheresed, and the T cells will be purified, activated, transduced and expanded ex vivo. On day 6 in the protocol, a single dose of 1 million CAR-T cells per kg will be administrated intravenously. The phenotypes of infused CAR-T cells, copy number of CAR transgene and plasma cytokines will be assayed for 2 years after CAR-T infusion using flow cytometry, real-time quantitative PCR and cytometric bead array, respectively. Moreover, several predictive plasma cytokines including interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, Soluble Interleukin (sIL)-2R-α, solubleglycoprotein (sgp)130, sIL-6R, Monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP1), Macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP1)-α, MIP1-β and Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), which are highly associated with severe cytokine release syndrome (CRS), will be used to forecast CRS to allow doing earlier intervention, and CRS will be managed based on a revised CRS grading system. In addition, patients with grade 3 or 4 neurotoxicities or persistent B-cell aplasia will be treated with dexamethasone (10 mg intravenously every 6 hours) or IgG, respectively. Descriptive and analytical analyses will be performed.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for the study was granted on 10 July 2014 (YLJS-2014-7-10). Written informed consent will be taken from all participants. The results of the study will be reported, through peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations and an internal organisational report.

Trial registration number

Keywords: IMMUNOLOGY, chimeric antigen receptor, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Third-generation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

CD19-targeting third-generation (3rd-G) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells modified by lentivirus are used for treating adults with r/r B cells-derived acute lymphoblastic leukaemia for the first time.

Twenty-four predictive plasma cytokines of severe cytokine release syndrome (CRS) are used to forecast CRS development, and a revised CRS grading system is adopted to manage severe CRS.

The study is not designed to compare the safety and efficacy of 3rd-G CAR-T cells to that of second-generation cells.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is a highly heterogeneous disease and is divided into three groups including B cells-derived (B-ALL), T cells-derived ALL and mixed lineage acute leukaemias based on immunophenotype. Among them, the most of ALL cases are B-ALL (∼74%) including early pre-B-ALL (∼10%), common ALL (∼50%), pre-B-ALL (∼10%), mature B-ALL (∼4%). Despite the fact that B-ALL occurs in children and adults, the prognosis of the two groups varies. Five-year survival rate of B-ALL in children was increased to more than 80%, whereas the prognosis is not as optimistic in adults.1 Many high-risk cases and special subgroups (such as r/r B-ALL) still lack efficient treatment. Moreover, clinicians face huge challenges in treating severe complications caused by the side effects of chemotherapy. Therefore, innovative approaches to further increase cure rate and improvement in quality of life are urgently needed for r/r adult B-ALL.

Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells

Cancer immunotherapy attempts to harness the power and specificity of the immune system to fight against cancer and has made five major breakthroughs (sipuleucel-T, ipilimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab and atezolizumab).2–7 T cells, as an attractive mediator of immunotherapy, have a specific inhibitory effect on the implantation and growth of cancer cells.8

Numerous studies demonstrated that their fully competent activation requires three signals including T-cell receptor engagement (signal 1), co-stimulation (signal 2) and cytokine stimulus (signal 3).9 However, B-lineage malignancies, for example B-ALL, generally lack signal 2 by absence of ligands of two major T-cell co-stimulatory molecules CD28 or 4-1BB. The lack of these ligands leads to rapid apoptosis of T cells after stimulation and immune escape of B-ALL cells.10 11 Therefore, the integration of signals 1 and 2 into a kind of functional proteins (such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)) expressed on T cells by gene engineering contributes to resolve these problems for B-ALL, and CAR-T therapy has become a promising strategy to treat patients with B-ALL.

As we all know, CAR-T therapy harnesses antibody specificity, homing, tissue penetration and target destruction of T cells to fight cancers. It has following two advantages. For one, CAR functions are independent of Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules, and it contributes to overcoming HLA class I molecules downregulation which is one of tumour immune escape mechanisms; for another, target selection of CAR is not limited to protein antigens. The CAR-T cell prototype was first reported for the study of roles of Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules in T-cell activation by the Israeli immunologist Zelig Eshhar in 1989.12 However, the subsequent clinical results are disappointing due to poor persistence of the first-generation CAR-T cells in vivo, prompting the later incorporation of co-stimulatory signal domains from CD28, 4-1BB, CD134 or inducible co-stimulator into the CAR intracellular structure.11 13 14 The incorporation of these domains improved the persistence of CAR-T in preclinical and clinical study significantly, and achieved promising results in patients with B cells-derived tumours, especially B-ALL using second-generation (2nd-G) CAR-T therapy carrying CD28 or 4-1BB signal domains (table 1). However, the two domains determine different functional properties of CAR-T cells, for example, CD28-based CARs direct an immediate antitumour potency, whereas 4-1BB-based CARs have the capacity for long-term persistence.34 Do the third-generation (3rd-G) CARs combining 4-1BB and CD28 signalling domains have these two different functional properties for T cells? Although preclinical study showed that 3rd-G CAR-T cells had a higher activation status than that of 2nd-G,35 there is no clinical evidence yet for using them in treating patients with B-ALL. Therefore, a phase I clinical trial will be conducted to treat r/r B-ALL using anti-CD19 3rd-G CAR-T cells.

Table 1.

Selected clinical trials of anti-CD19 CAR-T for treatment of B-ALL

| Institute | CAR generation | Year | Patients | Number of ORS | Comments | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCH | 2nd-G (4-1BB) | 2016 | 36 | 91% | 91% MRD negative CR | 15 |

| MSKCC | 2nd-G (CD28) | 2015 | 44 | 84% | 84% CR; MRD negativity following CAR-T treatment is highly predictive of survival; many transition to allo-HSCT, serum CRP as a reliable indicator for the severity of CRS | 16–19 |

| NCI | 2nd-G (CD28) | 2015 | 39 | 61% | 61% CR; a dose-escalation trial | 20 21 |

| 2016 | 5 | 80% | 80% MRD negative CR; first allogeneic CAR without causing GVHD | 22 23 | ||

| UPENN | 2nd-G (4-1BB) | 2016 | 59 | 93% | 93% CR | 24 25 |

| 2016 | 8 | 50% | First humanised CAR in patients refractory to murine CAR | 26 | ||

| BCM | 2nd-G (CD28) | 2013 | 4 | 25% | First allogeneic CAR | 27 |

| CPLAGH | 2nd-G (4-1BB) | 2015 | 9 | 56% | First allogeneic CAR with causing GVHD | 28 |

| FHCRC | 2nd-G (CD28) | 2016 | 33 | 94% | First CAR with defined CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets | 29 30 |

| UTMACC | 2nd-G (CD28) | 2016 | 17 | 53% | First CAR generated using Sleeping Beauty | 31 |

| FAHZU | 2nd-G (4-1BB) | 2016 | 1 | 100% | First cerebral CRS | 32 |

| CAYB | 4th-G (CD28, 4-1BB, CD27) | 2016 | 50 | 88% | First 4th-G CAR with 86% CR | 33 |

2nd-G, second-generation; 4th-G, fourth-generation; BB, no fullname, 4-1BB is alternatively known as CD137 or TNFRSF9 (tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9); BCM, Baylor College of Medicine; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CAYB, China America Yuva Biomed; CPLAGH, Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital; CR, complete remission; CRP, C reactive protein; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; FAHZU, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University; FHCRC, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; HSCT, Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ORS, objective responses; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; MRD, minimal residual disease; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; NCI, National Cancer Institute; SCH, Seattle Children's Hospital; UPENN, University of Pennsylvania; UTMACC, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Methods

Study design

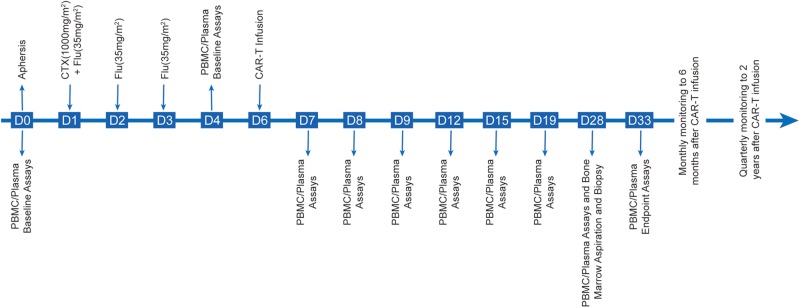

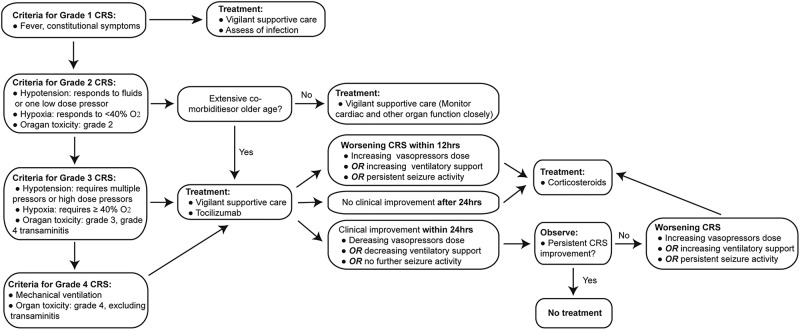

The phase I clinical trial (ClinicalTrial.gov number: NCT02186860) will be conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of anti-CD19 3rd-G CAR-T cells in patients with r/r B-ALL. We plan to enrol five patients from our clinical database for this trial, and the key inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in box 1. The general protocol schema and anti-CD19 3rd-G CAR structure are shown in figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Box 1. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study.

Inclusion criteria:

CD19+ B cell-derived acute lymphoblastic leukaemia as confirmed by immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry;

Chemotherapy relapsed or refractory, relapsed as defined by first or greater bone marrow relapse, refractory as defined by not achieving a complete remission (morphology <5% blasts) after two cycles of a standard chemotherapy regimen;

Male and female patients 18–65 years of age;

No available curative treatment options (such as haematopoietic stem cell transplantation);

Adequate organ function defined as: creatinine <2.5 mg/dL, aspartate transaminase–alanine transaminase ratio <3×upper limit of normal range, bilirubin <2.0 mg/dL;

Karnofsky performance status ≥60;

Expected survival time >3 months;

Adequate venous access for apheresis;

Ability to understand and give informed consent;

Measurable, morphological disease in the bone marrow (≥5% blasts).

Exclusion criteria:

Pregnant or lactating women;

Patients requiring T-cell immunosuppressive therapy;

Active central nervous system leukaemia;

Any concurrent active malignancies;

Patients with a history of a seizure disorder or cardiac disorder;

Previous treatment with any immunotherapy products;

Patients with HIV, hepatitis B or C infection;

Patients received haematopoietic stem cell transplantation;

Uncontrolled active infection.

Figure 1.

The general study schema. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Figure 2.

Anti-CD19 3rd-G CAR structure including FMC63 single-chain variable fragment (scFv), CD8α hinge and transmembrane, CD28 and 4-1BB signalling domains, and CD3ζ.e. 3rd-G, third-generation; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor.

In brief, adequate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from eligible participants will be leukapheresed for CAR-T production, and baseline copy number of CAR transgene and cytokines in plasma will be assayed on days 0 and 4. The T cells will be purified, transduced with lentivirus-expressing anti-CD19 3rd-G CAR and expanded in vitro with interleukin (IL)-7 and IL-15. On days 1–3, the patients will receive a lymphodepleting conditioning regimen consisting of cyclophosphamide (1000 mg/m2×1 day) and fludarabine (35 mg/m2×3 days) prior to CAR-T infusion. All participants will be administrated with a single infusion of one million CAR-T cells per kg on day 6. After intravenous (IV) infusion of CAR-T cells, the phenotypes of infused CAR-T cells, the copy number of CAR transgene and cytokines in plasma will be assayed on days 7–33. On day 28, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy will also be conducted. After day 33, observation and monitoring will be conducted monthly until 6 months after the infusion of CAR-T cells. Then, the same observation and monitoring will be conducted quarterly until 2 years after CAR-T infusion.

The FMC63 serves as CD19 antigen binding domain. The CD8α hinge domain contributes to bind CD19 antigen, which is close to membrane of tumour cells. The CD8α transmembrane domain is used to fix anti-CD19 CAR molecules on the membrane of T cells. The CD28 and 4-1BB signalling domains provide co-stimulation signals for T-cell activation. The CD3ζ transduces activating signals and activates T cells if the anti-CD19 CAR on these cells binds to CD19 antigens.

Generation of anti-CD19 3rd-G CAR-T cells

PBMCs will be obtained from eligible participants by leukapheresis and anti-CD19 3rd-G CAR-T cells will be generated as follows. Briefly, T cells from the leukapheresis product will be isolated and activated using Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 magnetic beads (Invitrogen Life Technologies). After 2–3 days of activation, the activated T cells will be transduced with lentivirus-expressing anti-CD19 3rd-G CAR in 24-well plates pretreated with RetroNectin (Takara) and then further expanded with X-VIVO 15 media (Lonza) containing IL-7 and IL-15 (5 ng/mL) to achieve the desired anti-CD19 3rd-G CAR-T cell dose.

Study objectives

The primary objective of this study is to assess the safety of a fixed single dose of autologous 3rd-G CAR-T cell infusion. Adverse events and laboratory values will be graded with the use of the National Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, V.3.0. All adverse events will be reported until the time of objective disease progression. The second objectives are to measure the antitumour response and persistence of 3rd-G CAR-T cells in vivo.

Immune monitoring

According to the general study schema, whole-blood samples will be collected for the assay of redirected T-cell subsets (naïve, central memory, effector memory and effector T cell), CAR transgene persistence and plasma cytokines (interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-6, IL-8, sIL-2R-α, sgp130, sIL-6R, MCP1, MIP1-α, MIP1-β, and GM-CSF) using flow cytometry, quantitative PCR and cytometric bead array, respectively. On day 28, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy will be performed. The levels of plasma cytokines will be used for prediction of severe cytokine release syndrome (CRS) development.

Management of 3rd-G CAR T-cell toxicities

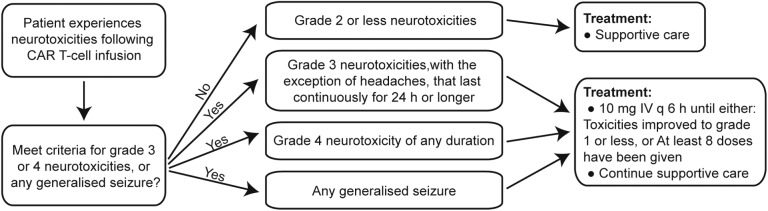

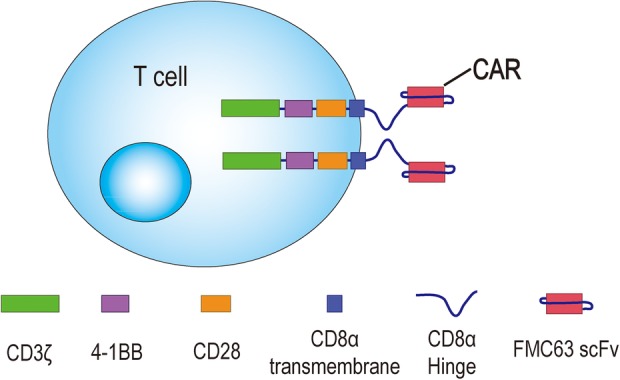

The most significant and life-threatening complication associated with CAR-T infusion is CRS, which is a non-antigen-specific toxicity that occurs as a result of high-level immune activation and is characterised by fever, nausea, myalgias, capillary leak, hypoxia and hypotension. The symptoms usually coincide with in vivo CAR-T expansion and elevation of certain serum cytokines, and occur a few days after CAR-T infusion but can be as early as 24 hours depending on the co-stimulatory domains in the CAR structures. Apart from identification of accurate predictors for CRS, the ability to manage CRS is vital to protect patient safety after CAR-T cell therapy. Therefore, the following treatment algorithm for the management of CRS based on a revised CRS grading system was proposed by Lee DW36 and will be adopted in the current study (figure 3). For neurotoxicities due to CAR-T cells might in some cases, will be managed as follows. Briefly, dexamethasone (10 mg IV every 6 hours) will be given for grade 3 neurotoxicities other than headaches lasting more than 24 hours, grade 4 neurotoxicities of any duration and for any seizures (figure 4).37 In addition, patients with persistent B-cell aplasia will be administered IV IgG when the serum IgG level is <400 mg/dL in this study because persistent B-cell aplasia caused by CAR-T cells could result in an increased risk of infection.

Figure 3.

CRS treatment algorithm. CRS, cytokine release syndrome.

Figure 4.

Neurotoxicities treatment algorithm. CRS, cytokine release syndrome; IV Q6h, intravenously every 6 hours.

Data management

A trial management committee was formed by our study team members. The data are collected, cleaned and sent to the committee by AZ and D-HW on a weekly basis, and meetings are held with principle investigator on monthly basis to discuss the trial's progress. All data are double-entered to a computer to prevent data entry errors. The transfer of the data is encrypted to protect patients' confidentiality.

Statistical analysis

The variables will be analysed using GraphPad Prism V.5.0, and the results will be shown as the mean and SD. Two-way analysis of variance was used to determine the significance of the differences between the means in all experiments, and p values of <0.05 will be assumed to be statistically significant.

Ethical issue

The trial will be conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2008). Written informed consent will be taken from all participants by the study physician. Patients will be free to withdraw from the trial at any time and their information will be restricted to the study physician. This trial protocol received Institutional Review Board approval in July 2014.

Dissemination

The participants, healthcare professionals, the public and other relevant groups will be informed of the study results, and the results will be published in a peer-reviewed journal after the completion of the trial.

Discussion

There are about 9000 new cases (0.69 per 100 000) of ALL in the China each year, and over 80% of adult ALL will attain a complete remission with standard induction regimens. Regardless of further consolidation therapy and maintenance chemotherapy, up to 20% of patients will be refractory to initial therapy and an additional 30%–60% of patients will relapsed. The long-term leukaemia-free survival rate is <50% and most patients with r/r ALL will die of their disease.38 For this reason, CAR-T cell therapy, engineering T cells with a CAR that alters T-cell specificity and function to recognise tumour antigens, is under investigation for the treatment of r/r adult B-ALL. Obviously, target selection is essential for the success of CAR-T immunotherapy. Several targets can be used for anti-B-ALL CAR-T development, such as CD19, CD22, CD20, CD24 and so on. Among these targets, CD19 is the most promising one for CAR-T cell of B-ALL because of its wide expression by malignant B cells, including most lymphomas and lymphocytic leukaemias, and is highly restricted to normal mature B cells and B-cell precursors without impairing the haematopoietic stem cells.39 40

To date, there are 12 phase I/II trials using anti-CD19 CAR-T for B-ALL (as shown in table 1). Eleven trials (∼92%) selected 2nd-G CAR carrying CD28 or 4-1BB domains, and these 2nd-G CAR-T cells have achieved promising results in patients with B-ALL. Furthermore, three products including CTL019 (Novartis, Switzerland), JCAR015 (Juno therapeutics, USA) and KTE-C19 (Kite Pharma, USA) were granted breakthrough therapy designation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, distinct signalling of CD28 or 4-1BB co-receptors have different influence on the metabolic characteristics of CAR-T cells and balance the response towards long-term persistence (long-lived memory) or immediate antitumour potency (short-lived effect cells). Moreover, a preclinical study showed that 3rd-G CAR-T cells combining CD28 and 4-1BB co-receptors had superior in vitro activation and proliferation capacity compared with 2nd-G CAR-T cells carrying CD28 signal domains, and both kinds of cells displayed in vivo comparable efficacy in eliminating CD19+ B cells.35 Another preclinical study demonstrated that in vivo persistence of 3rd-G CAR-T cells was inferior to that of 2nd-G ones.41 But there is a lack of clinical data of 3rd-G CAR-T cells in patients. Thus, the safety and efficacy of these cells should be investigated in patients with B-ALL.

CRS, as the most common severe adverse event, occurs a few days after CAR-T therapy and usually results from in vivo CAR-T proliferation and dramatic elevation of several serum cytokines including IL-6 and IFN-γ. Unfortunately, the CRS observed in clinical trials have not been exactly reproduced in mouse model systems and these leukaemia xenograft models may not be fit for further investigation of long-term effects of CAR-T cells. For one, engrafted human CAR-T cells may be challenged by residual elements of the immune system from immunocompromised mice. For another, it is difficult to assess CAR-T toxicity because human CD19 expression profile may not be equivalent to that of mouse.41 Therefore, the ability to predict and manage severe CRS in clinical trials is vital to protect patients' interests because early interventions could limit the efficacy of CAR-T immunotherapy while the late ones could increase morbidity and mortality of treated patients. For this reason, a novel CRS severity grading system and a treatment algorithm for CRS management based on severity was proposed 2 years ago (as shown in figure 3). Furthermore, some predictive biomarkers for CRS were recently identified, and the authors found that peak levels of 24 cytokines including IFN-γ, IL-6, sgp130 and sIL-6R in the first month after CAR-T infusion were highly associated with severe CRS.42 In addition, preclinical results from our lentiviral technology provider demonstrated that CD19-targeting 3rd-G CAR-T cells were efficient in the elimination of leukaemia xenograft.43 Therefore, a phase I clinical trial using a revised CRS grading system and severe CRS predictive biomarkers for CRS management is conducted for the first time in adult patients with r/r ALL to assess the safety and efficacy of CD19-targeting 3rd-G CAR-T cells modified by lentivirus.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Hao Liu for English editing of the manuscript. The generous participation and contributions of the volunteers in the study are very gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Contributors: X-YT, BZ and HC conceptualised the idea. HC, BZ and D-HW designed the study. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing. All authors reviewed the protocol. X-YT, G-LH, YS, WC and AZ will conduct the analyses. HC is the principle investigator.

Funding: This work is funded by a grant from Clinical Feature and Application Research of Capital (grant number Z111107058811107).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Approved by the Institutional Review Board at Affiliated Hospital of Academy of Military Medical Sciences, China.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The technical appendix, statistical code and data set are available from the corresponding author at chenhu217@aliyun.com. The participants gave informed consent for the data sharing.

References

- 1.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet 2008;371:1030–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:411–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:265–77. 10.1038/nrc3258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:711–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 2015;372:320–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2018–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2016;387:1909–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00561-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.June CH. Adoptive T cell therapy for cancer in the clinic. J Clin Invest 2007;117:1466–76. 10.1172/JCI32446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keppler SJ, Rosenits K, Koegl T et al. Signal 3 cytokines as modulators of primary immune responses during infections: the interplay of type I IFN and IL-12 in CD8 T cell responses. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e40865 10.1371/journal.pone.0040865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imai C, Mihara K, Andreansky M et al. Chimeric receptors with 4-1BB signaling capacity provoke potent cytotoxicity against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2004;18:676–84. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kowolik CM, Topp MS, Gonzalez S et al. CD28 costimulation provided through a CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer Res 2006;66:10995–1004. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross G, Waks T, Eshhar Z. Expression of immunoglobulin-T-cell receptor chimeric molecules as functional receptors with antibody-type specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989;86:10024–8. 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finney HM, Akbar AN, Lawson AD. Activation of resting human primary T cells with chimeric receptors: costimulation from CD28, inducible costimulator, CD134, and CD137 in series with signals from the TCR zeta chain. J Immunol 2004;172:104–13. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milone MC, Fish JD, Carpenito C et al. Chimeric receptors containing CD137 signal transduction domains mediate enhanced survival of T cells and increased antileukemic efficacy in vivo. Mol Ther 2009;17:1453–64. 10.1038/mt.2009.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner RA, Finney O, Smithers H et al. Prolonged functional persistence of CD19CAR t cell products of defined CD4:CD8 composition and transgene expression determines durability of MRD-negative ALL remission. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(Suppl); abstr 3048. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brentjens RJ, Riviere I, Park JH et al. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood 2011;118:4817–28. 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:177ra38 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davila ML, Riviere I, Wang X et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:224ra25 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park JH, Riviere I, Wang X et al. Implications of minimal residual disease negative complete remission (MRD-CR) and allogeneic stem cell transplant on safety and clinical outcome of CD19-targeted 19-28z CAR modified T cells in adult patients with relapsed, refractory B-cell ALL. Blood 2015;126:682. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2015;385:517–28. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DW, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yuan CM et al. Safety and response of incorporating CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in typical salvage regimens for children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2015;126:684. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brudno JN, Somerville RP, Shi V et al. Allogeneic T cells that express an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor induce remissions of B-cell malignancies that progress after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation without causing graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1112–21. 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.5929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brudno JN, Somerville R, Shi V et al. Allogeneic T-cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor cause remissions of B-cell malignancies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without causing graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2015;126:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1507–17. 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maude SL, Teachey DT, Rheingold SR et al. Sustained remissions with CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells in children with relapsed/refractory ALL. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(Suppl); abstr 3011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maude SL, Barrett DM, Rheingold SR et al. Efficacy of humanized CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells in children with relapsed ALL. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(Suppl); abstr 3007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cruz CR, Micklethwaite KP, Savoldo B et al. Infusion of donor-derived CD19-redirected virus-specific T cells for B-cell malignancies relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant: a phase 1 study. Blood 2013;122:2965–73. 10.1182/blood-2013-06-506741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai H, Zhang W, Li X et al. Tolerance and efficacy of autologous or donor-derived T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors in adult B-ALL with extramedullary leukemia. Oncoimmunology 2015;4:e1027469 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1027469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turtle CJ, Hanafi LA, Berger C et al. CD19 CAR-T cells of defined CD4+:CD8+ composition in adult B cell ALL patients. J Clin Invest 2016;126:2123–38. 10.1172/JCI85309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turtle CJ, Hanafi LA, Berger C et al. Rate of durable complete response in ALL, NHL, and CLL after immunotherapy with optimized lymphodepletion and defined composition CD19 CAR-T cells. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(Suppl); abstr 102. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kebriaei P, Singh H, Huls MH et al. Phase I trials using Sleeping Beauty to generate CD19-specific CAR T cells. J Clin Invest 2016;126:3363–76. 10.1172/JCI86721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu Y, Sun J, Wu Z et al. Predominant cerebral cytokine release syndrome in CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cell therapy. J Hematol Oncol 2016;9:70 10.1186/s13045-016-0299-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong L, Chang L, Gao Z et al. Chimeric antigen receptor 4SCAR19-modified T cells in acute lymphoid leukemia: a phase II multi-center clinical trial in China. Blood 2015;126:3774. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Stegen SJ, Hamieh M, Sadelain M. The pharmacology of second-generation chimeric antigen receptors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015;14:499–509. 10.1038/nrd4597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karlsson H, Svensson E, Gigg C et al. Evaluation of intracellular signaling downstream chimeric antigen receptors. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0144787 10.1371/journal.pone.0144787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee DW, Gardner R, Porter DL et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood 2014;124:188–95. 10.1182/blood-2014-05-552729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN. Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: recognition and management. Blood 2016;127:3321–30. 10.1182/blood-2016-04-703751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frey NV, Luger SM. How I treat adults with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2015;126:589–96. 10.1182/blood-2014-09-551937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haso W, Lee DW, Shah NN et al. Anti-CD22-chimeric antigen receptors targeting B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2013;121:1165–74. 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kochenderfer JN, Rosenberg SA. Treating B-cell cancer with T cells expressing anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:267–76. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalaitsidou M, Kueberuwa G, Schutt A et al. CAR T-cell therapy: toxicity and the relevance of preclinical models. Immunotherapy 2015;7:487–97. 10.2217/imt.14.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teachey DT, Lacey SF, Shaw PA et al. Identification of predictive biomarkers for cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor t-cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Discov 2016;6:664–79. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bai Y, Kan S, Zhou S et al. Enhancement of the in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy of CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells through the delivery of modified TERT mRNA. Cell Discov 2015;1:15040 10.1038/celldisc.2015.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]