Abstract

Objectives

Prior work has examined the shape of the income–mortality association, but work has not compared gradients between countries. In this study, we focus on changes over time in the shape of income–mortality gradients for 4 Nordic countries during a period of rising income inequality. Context and time differentials in shape imply that the relationship between income and mortality is not fixed.

Setting

Population-based cohort study of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

Participants

We collected data on individuals aged 25 or more in 1995 (n=12.98 million individuals, 0.84 million deaths) and 2003 (n=13.08 million individuals, 0.90 million deaths). We then examined the household size equivalised disposable income at the baseline year in relation to the rate of mortality in the following 5 years.

Results

A steep income gradient in mortality in men and women across all age groups except the oldest old in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. From the 1990s to 2000s mortality dropped, but generally more so in the upper part of the income distribution than in the lower part. As a consequence, the shape of the income gradient in mortality changed. The shift in the shape of the association was similar in all 4 countries.

Conclusions

A non-linear gradient exists between income and mortality in most cases and because of a more rapid mortality decline among those with high income the income gradient has become steeper over time.

Keywords: income, health inequality, mortality, cohort study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study documents that a non-linear income–mortality association exist among men and women in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden at all ages except among the oldest old.

From the 1990s to the 2000s the income–mortality gradient generally became steeper. The relationship between income and mortality has rapidly changed.

This cross-country comparison study is based on individual-level data from population-covering registers, so bias from self-selection or self-report of information is limited.

The findings of this study do not add any new knowledge of the mechanisms behind the association between income and mortality.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the research area of socioeconomic inequalities in health has been growing tremendously. Hence, we have ample evidence on the association between income and various health outcomes in most countries. While this association seems to exist across the whole income spectrum most studies in developed industrialised countries suggest diminishing marginal returns of income on health, both with regard to self-rated health,1 2 biological risk markers3 and mortality.4–7

Simultaneously with this surge of interest in health inequalities, most Western countries have witnessed a profound increase of inequality in the distribution of income.8 It has become a key issue for science, as well as for the political scene, to try to grasp what consequences and impacts such changes might have. The Nordic countries, where the levels of inequality in income and wealth in the 1960s and 1970s were extremely low in an international perspective, have not been immune to these global megatrends—growth of income inequality has been particularly sharp here.9–11 Between 1995 and 2008, the Gini coefficient increased by 29% in Finland and Sweden, 24% in Denmark, while the increase in Norway was rather modest (5%) with extreme variation between the years.9 The latter due to changes in taxation rules for capital income during specific years.

In this paper, we will estimate the income–mortality gradient from a comparative perspective with a focus on changes over time. In addition, earlier research on income and mortality has paid much less attention to mortality at older ages, despite the fact that most deaths occur in old age. Studies that do examine social inequalities in mortality in old age suggest that they resemble those in working age.12 13 We therefore study the influence of age on the relationship. The relationship between income and health is an effect of a complex time pattern of causality and selection, and it is difficult to unpick these two mechanisms.14 However, a thorough study of the shape of the association between income and mortality as such may be important for suggesting potential pathways and social interventions, it is nevertheless important to monitor how the income–mortality gradient changes as income inequalities have increased. The observed increase in income inequalities does not necessarily lead to changes in people's relative income position within a society; therefore, any changes in the income–mortality gradient could be indicative of the importance of absolute differences in income. A recent American study showed that the shape of the association is becoming steeper,15 but it is unclear whether this would generalise to Nordic countries, which have labour markets and welfare state programmes that are arguably very different to the USA. However, the four countries are also different to each other in ways that may influence the income–mortality gradient.16 The countries have been on slightly different economic trajectories, have been hit by booms and busts at different times, and, as already noted, have experienced varying income inequality trends. They are also quite different in terms of mortality trajectories, where particularly Denmark's poor performance is well known.17 In addition, in examining temporal and spatial differences, our findings have implications for how changeable the income–mortality relationship is, which is of broader relevance for income-related policies and their influence on population health.

We do so by analysing the shape and the possible changes of the shape of the income–mortality gradient in the Nordic countries using our ability to analyse large-scale harmonised microdata from registers. Our research questions are: (1) Do we find evidence for a non-linear association with steeper income gradients in mortality at the low end of the income distribution as compared with at the high end in the Nordic countries? (2) Do we find evidence for changes in the shape of the association over time? (3) Do we find cross-national variation in the association between income and mortality within the Nordic countries? (4) Do we find a similar, or different, association between income and mortality in different age groups?

Materials and methods

We selected two cohorts of the total populations in each country, alive and aged at least 25 at baseline in 1995 and 2003, except in Finland where instead of a total sample an 11% random sample of population with an oversample covering 80% of persons deceased during the study period was used. Probability weights were used to account for the sampling design in the analyses using the Finnish data, where each person has a weight depending on whether the person was included in the 11% sample of total population or the 80% sample of deaths. Weights correct the unequal sampling probability of these two parts of the data. For Norway, immigrants arriving in 1993 and later were not included. However, the relatively limited number of immigrants arriving to Norway these years, especially in middle-aged and older age categories, means that this is unlikely to influence results. These cohorts were then followed for 5 years for mortality from all causes, resulting in mortality measures from 1996 to 2000 and from 2004 to 2008 for respective cohort. Data on disposable income—including all taxable income of all household members and taking into account taxes and income transfers—were collected at baseline, and adjusted for household size. Income was categorised into 20 equally sized groups for each country at each of the two baselines. Age at baseline was recorded in 5-year groups from age 25 to 94 (25–29,…,90–94) and an open-ended category of 95 years or higher. Risk time was counted from the end of the calendar year where disposable income was measure until either death or the end of the fifth year of follow-up.

Data are gathered from official registers in the four countries. The different registers are linked for income and mortality on the individual level within each country; we aggregated data from these registers and combined them into one data set. For Denmark, data on income comes from the Integrated Database for Labour Market Research, and data on mortality comes from the Danish Causes of Death Register. For Finland, data on income come from the Finnish Tax Administration and the Social Insurance Institution, and data on mortality come from Statistics Finland. For Norway, the data on income come from the Norwegian Tax Register, while data on mortality come from the Statistics Norway. For Sweden, the data come from a multiple-linked register data of national routine registers, the Swedish Work and Mortality Data.18

Statistical analysis

The counts of deaths and the total time at risk were used in a modified Poisson regression, where we used the quasi-likelihood approach of McCullagh to account for extra-Poisson variation by introducing a dispersion parameter in the model that allows for the variance to be proportional to the mean.19 The effect of age and income on mortality was modelled with a two-dimensional P-spline.20 We used β-splines with 3 degrees of freedom as the basis of the P-spline. The smoothing parameter was selected using the Bayes Information Criterion (BIC). The local model fit was evaluated by comparing the stratum-specific observed and predicted mortality rates. Separate analyses were conducted by country, baseline year, sex and age (stratified by age 25–64 and age 65 and over). We used the predicted age-specific and income-specific mortality rates to calculate age-standardised mortality rates based on the 2010 European Standard Population.21

Results

The characteristics of the samples are given in table 1. As seen in total, across cohorts and countries, we analysed around 26 000 000 observations. The Finnish sample has a high number of deaths relative to the number of individuals and the time at risk because of the sampling design used.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Denmark 95 | Denmark 03 | Finland 95 | Finland 03 | Norway 95 | Norway 03 | Sweden 95 | Sweden 03 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons | 3 484 869 | 3 624 905 | 739 359 | 525 630 | 2 870 367 | 2 955 494 | 5 984 517 | 6 079 098 |

| Deaths | 286 820 | 270 140 | 170 388 | 164 022 | 216 718 | 201 746 | 459 509 | 444 571 |

| Risk time (million years) | 16.69 | 17.44 | 3.28 | 2.22 | 13.81 | 14.27 | 28.55 | 29.06 |

| Male (%) | 51.69 | 51.71 | 51.13 | 50.87 | 51.49 | 51.09 | 51.46 | 51.26 |

| Aged 25–29 | 368 476 | 323 530 | 39 360 | 34 157 | 328 530 | 263 215 | 609 156 | 523 487 |

| Aged 30–34 | 385 736 | 356 232 | 44 319 | 34 481 | 316 529 | 311 857 | 618 411 | 575 452 |

| Aged 35–39 | 357 249 | 400 048 | 47 817 | 41 134 | 309 020 | 322 499 | 574 479 | 633 544 |

| Aged 40–44 | 353 540 | 372 412 | 54 633 | 43 054 | 300 356 | 304 457 | 574 120 | 570 888 |

| Aged 45–49 | 380 852 | 354 586 | 64 819 | 46 932 | 307 346 | 301 772 | 634 705 | 562 821 |

| Aged 50–54 | 351 585 | 348 562 | 52 927 | 52 222 | 250 182 | 288 993 | 591 274 | 573 443 |

| Aged 55–59 | 269 847 | 381 878 | 51 239 | 48 826 | 193 004 | 290 718 | 450 126 | 626 435 |

| Aged 60–64 | 233 337 | 291 984 | 56 588 | 38 891 | 173 985 | 204 459 | 396 974 | 491 131 |

| Aged 65–69 | 218 375 | 231 513 | 72 532 | 37 151 | 180 569 | 163 179 | 396 037 | 387 091 |

| Aged 70–74 | 203 213 | 187 788 | 80 874 | 41 510 | 183 078 | 153 878 | 397 139 | 345 634 |

| Aged 75–79 | 160 492 | 159 248 | 72 674 | 41 777 | 151 697 | 142 352 | 328 630 | 316 274 |

| Aged 80–84 | 113 953 | 118 123 | 61 036 | 33 576 | 101 051 | 116 867 | 232 558 | 261 321 |

| Aged 85–89 | 62 035 | 65 173 | 31 492 | 21 720 | 52 635 | 62 839 | 128 412 | 141 391 |

| Aged 90–94 | 21 631 | 27 334 | 7977 | 8688 | 19 678 | 25 036 | 43 616 | 57 153 |

| Aged 95 and older | 4548 | 6494 | 1072 | 1511 | 2707 | 3373 | 8880 | 13 033 |

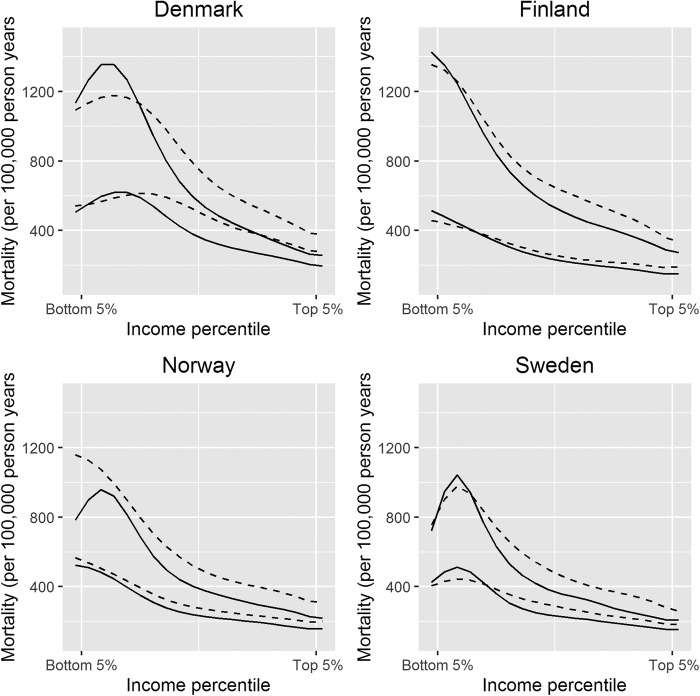

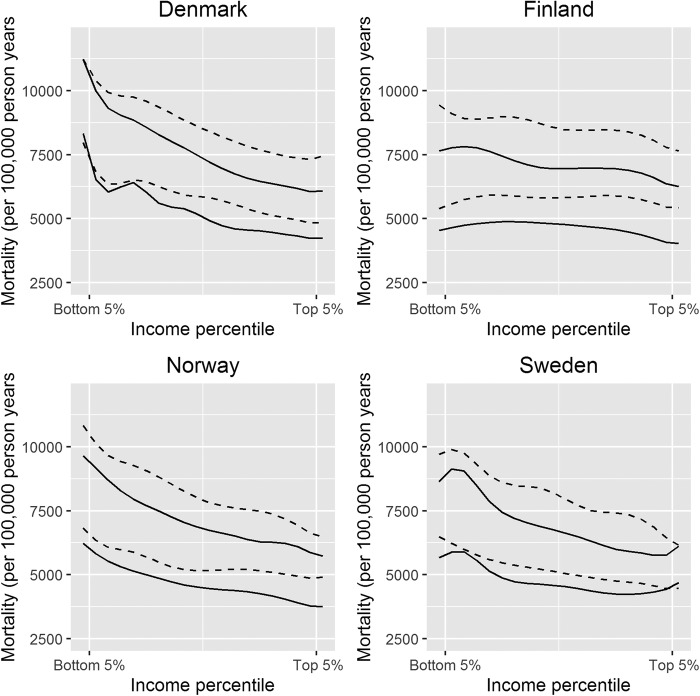

When we examined the age-standardised mortality among those aged 25–64 at baseline, we observed a similar change in the shape of the income gradient for men and women in all four countries. Mortality decreases the most for those above the median, which causes the income gradient to become steeper below the median, then relatively unchanged above (figure 1). One notable exception to this pattern is the change among men with incomes below the 10th centile in Norway, where mortality drops substantially. We also calculated the inflection percentile for each graph (see table 2). The inflection percentile is the point in the income distribution where the deceleration in the age-standardised mortality over adjacent categories is the strongest. Visually, the inflection percentile is the point of the graph where the curve changes direction from concave to convex, or reversed. Inspection of the inflection percentiles confirms the impression that the shape is steepest below the median, and that the inflection points move down in the income distribution over time, particularly in Denmark. When we looked at individuals aged 65 or more at baseline, we observed a much less steep income gradient in mortality, particularly in Finland where no gradient was observed. It should be noted that in absolute terms the difference between the top and bottom income percentiles among those aged 65 or more are larger due to the higher mortality in these ages, the comparisons of the gradients are therefore purely relative. We also observed less of a shift in shape as compared with the findings restricted to those aged between 25 and 64 at baseline (figure 2). If all individuals age 25 or more at baseline were included in the analysis, the age-standardised mortality resembled the association for those aged 65 years or more due to the influence of the age-standardisation weights used (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Age-standardised mortality for individuals aged 25–64 at baseline. Full-drawn lines are 2003, dotted lines are 1995. The upper set of lines in each plot is for men, the lower set is for women.

Table 2.

Age-standardised mortality at the inflection point in individuals aged 25–64 at baseline

| Country | Period | Sex | Inflection percentile | Age-standardised mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 1995 | Men | 40–44th | 882.42 |

| Denmark | 2003 | Men | 30–34th | 945.78 |

| Denmark | 1995 | Women | 50–54th | 487.81 |

| Denmark | 2003 | Women | 35–39th | 480.99 |

| Finland | 1995 | Men | 20–24th | 1042.38 |

| Finland | 2003 | Men | 20–24th | 960.22 |

| Finland | 1995 | Women | 25–29th | 351.94 |

| Finland | 2003 | Women | 20–24th | 372.04 |

| Norway | 1995 | Men | 25–29th | 796.2 |

| Norway | 2003 | Men | 20–24th | 770.53 |

| Norway | 1995 | Women | 25–29th | 393.71 |

| Norway | 2003 | Women | 25–29th | 349.94 |

| Sweden | 1995 | Men | 20–24th | 838.07 |

| Sweden | 2003 | Men | 20–24th | 770.53 |

| Sweden | 1995 | Women | 25–29th | 384.7 |

| Sweden | 2003 | Women | 25–29th | 358.68 |

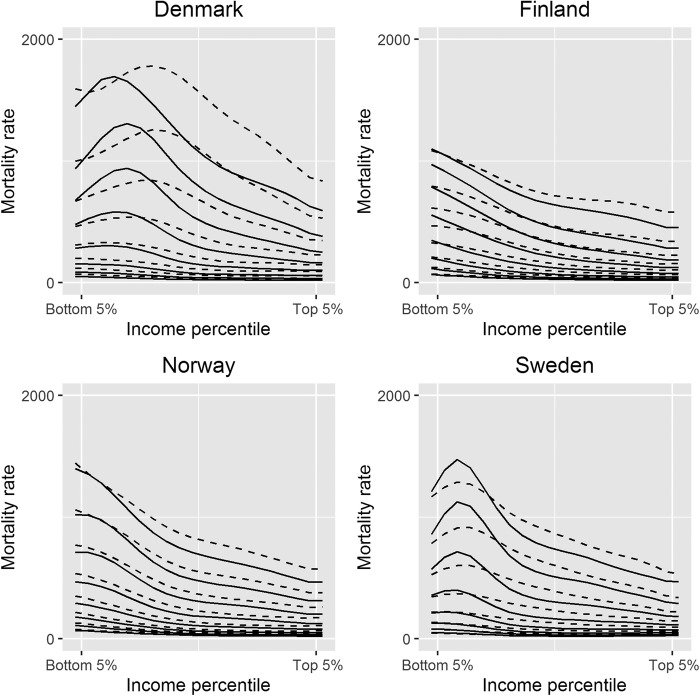

Figure 2.

Age-standardised mortality for individuals aged 65 or more at baseline. Full-drawn lines are 2003, dotted lines are 1995. The upper set of lines in each plot is for men, the lower set is for women.

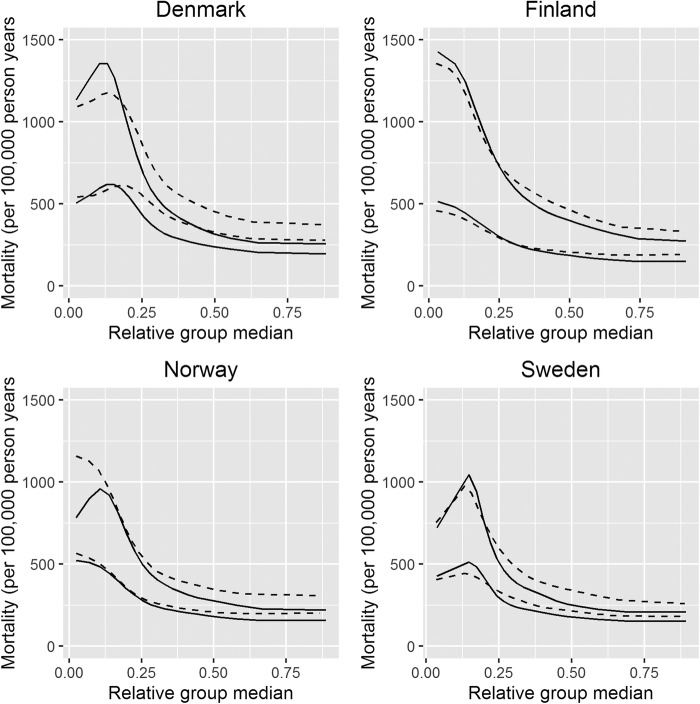

Since we so far have treated our income measure on a relative scale, the effects of changes in the distribution of income cannot readily be inferred from the findings. That is, our primary results are focused on changes in mortality at relative levels of the income distribution. To test the influence of changes in the distribution, we plotted the age-standardised mortality for all individuals 64 years or younger at baseline for each of the 20 categories at the median income of the category. This was done to take account of the fact that the absolute differences in income were much bigger between the top and bottom categories than between the middle categories. To make the figures comparable across time and between countries, we scaled the income axis to the difference in the median between the top 5% and bottom 5% income categories (figure 3). When compared with figure 1, the distances between the middle categories are compressed and the distances between the upper categories increased to illustrate the absolute differences in median income between the 20 categories. When compared with figure 1, the income-related inequality in mortality appears to be stronger, and the changes over time seem to benefit those with low incomes even less.

Figure 3.

Age-standardised mortality for individuals aged 25–64 at baseline plotted against the relative group median. Full-drawn lines are 2003, dotted lines are 1995. The upper set of lines in each plot is for men, the lower set is for women.

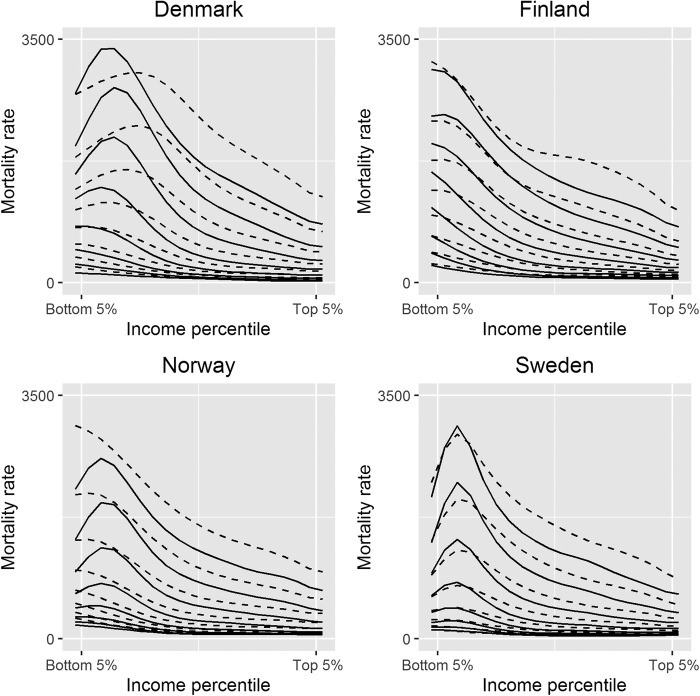

To compare the shape across age groups we present the associations between income and mortality rate stratified by age at baseline. The findings for men and women aged 25–64 are presented in figures 4 and 5, respectively. The associations for men and women aged 65 and over are shown in online supplementary figures S1 and S2. Our findings reproduce known differences between the countries. The results are striking in several respects. First, an association between income and mortality was present at all ages with the possible exception of the oldest old. This is consistently the case for men and for women in 1995 and in 2003 for all four countries. Second, there is a shallow or even positive income–mortality gradient in the lowest 10% of the income distribution among men and women aged 40–60 in Denmark and Sweden and also for men in Norway. Third, the drop in mortality from 1995 to 2003 appears to be much stronger at higher incomes than at lower. In fact, the mortality of men and women aged 45–64 in the lowest income groups generally increased in Denmark, Finland and Sweden or at least remained at the same level as in 1995.

Figure 4.

Association between age, income and mortality by age for men aged 25–64 at baseline. Full-drawn lines are 2003, dotted lines are 1995. There is a full-drawn and a dotted line for each 5-year age group, for example, the top two lines are for men aged 60–64 and the bottom two lines are men aged 25–29.

Figure 5.

Association between age, income and mortality by age for women aged 25–64 at baseline. Full-drawn lines are 2003, dotted lines are 1995. There is a full-drawn and a dotted line for each 5-year age group, for example, the top two lines are for women aged 60–64 and the bottom two lines are women aged 25–29.

bmjopen-2015-010974supp_figures.pdf (395KB, pdf)

Discussion

A steep income gradient in mortality exists across age groups and between genders in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Our findings document differences in the association according to sex and age, and a noticeable change in the shape of the association over a fairly short period of time. From 1995 to 2003 mortality dropped, but more in the upper part of the income distribution than in the lower part. As a consequence, the non-linearity of the income gradient in mortality became stronger. The shift in the shape of the association was similar in all four countries, but with some important differences. In Denmark and Sweden, the mortality was lower at the very bottom of the income distribution than at the 10th–15th centiles in 1995 and 2003. This finding at the low end of the income distribution was not observed in Finland, but was also seen among men in Norway in 2003, but not in 1995. This has been observed in Swedish income register data before,2 and we have conducted tests and sensitivity analyses on individual-level data in the Swedish registers without finding one conclusive answer to why these reversed patterns in the association is observed at the bottom of the income distribution. Therefore, we can only speculate on what causes this anomaly. It is likely not caused by only one factor; instead we suggest that it is driven by a number of factors: migration, non-taxable incomes as well as tax evasion in combination with some degree of measurement error for mortality and income. Thus, the disparities between the countries may reflect idiosyncrasies of the tax systems and in the efficiency of registering income and mortality.

The shape of the association is similar for men and women, but the strength of the gradient is clearly stronger for men. This is partly an effect of the lower absolute numbers of deaths among women, but could also be caused by a weaker relationship between income and mortality among women which other studies has noted before.22 23

With this study we make no claims of identifying causal pathways from income to health or vice versa. Many other studies have attempted this, but whether or not these efforts can be considered successful depends in large part on what one holds to be reasonable criteria for causal inference (see, eg, ref. 14 for a general discussion). Given the large potential for confounding, including the difficult problem of the potential impacts of morbidity on income, it is difficult to think of situations where exogenous variation could be identified that would allow for a study of causal effects of income for the whole adult population in the four countries at two points in time across age groups. Therefore, what we provide here should be considered a description of an association. The interpretation of why these associations came to be has to rest on assumptions that come from outside this study. Nevertheless, the relatively dramatic change in the shape of the association over a relatively short time period suggests that the income–mortality relationship is fairly flexible in nature, and influenced by macro trends that are not country specific. The specific macro trend that was one of the main motives for conducting this study has been the large increase in income inequality in the Nordic countries, a macro phenomenon that is commonly linked to health outcomes both in relative and absolute terms. From this standpoint, we would conclude, as others have done,24 that the findings in this study support the notion of a failure by the welfare state in its efforts to implement measures against health inequalities.

We found that the association between income and mortality was present at all ages except perhaps for the youngest and the oldest old, but that the association varied by age. In absolute terms, it is clear that the income gradient in mortality does increase with age, but appear to diminish from about age 75, where labour incomes have been long replaced with capital incomes and other retirement income arrangements. This pattern might follow if accumulated risk increases the steepness of the income–mortality gradient (through health selection, causation or both) over the course of working life, while the substantial decreases in income due to retirement (which is not a consequence of ill health) weakens the relative gradient. However, it is important to note that individuals with different ages at baseline belong to different birth cohorts, which might also explain the difference in association by age.

The remarkable similarity of the shift in shape over time in the four countries despite—among other things—considerable difference in mortality may indicate that there are cohort or period effects, which are common for individuals in the four countries. Furthermore, the processes behind the changes in the association between all-cause mortality and income can also be related to the cause of death-specific mortality trends in different income groups. The income–mortality association is to some extent different depending on what cause of death that is examined.25 There is evidence concerning Finland that specific causes of death contribute differently to the change in income gradient in all-cause mortality, mainly in ages 35–64 where decreasing deaths to cardiovascular diseases in all income groups is cancelled out by increased mortality to causes related to alcohol-related causes, particularly in the lowest income quintile.26 27

Studies have previously examined the shape of the association between income and mortality in different ways, many of them in the populations used for the analyses presented here.4 7 22 27–30 The shape of the association in this study is broadly consistent with what has previously been observed, but this study provides the opportunity for direct comparison between countries, changes over time and across age groups. In addition, there is an even larger literature on income inequality and mortality.31 This literature is not complete without connection to our purpose. As noted by Deaton14 and others, the shape of the income–mortality association within countries will affect the association between income inequality and mortality between them even in the absence of a causal effect of inequality in itself.32 33

In conclusion, we observe an income gradient in mortality in most cases up until the oldest old. If anything, the overall decline in mortality which has been stronger in the higher income groups has led to a strengthening of the income–mortality gradient and its non-linearity.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in the development of the study aim. Data were managed by LHM, JIE, JR and LT. Data analysis was performed by LHM and JR. The first draft was written by LHM and JF. All authors participated with comments and suggestions on the first draft. The second draft after review comments was revised by JR and JF.

Funding: This study is carried out as part of the Inequality Impacts project, funded by the Joint Committee for Nordic Research Councils for the Humanities and the Social Sciences (NOS-HS) 4.4-2015-61.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Permission to analyse aggregated data was obtained.

References

- 1.Mackenbach JP, Martikainen P, Looman CW et al. The shape of the relationship between income and self-assessed health: an international study. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:286–93. 10.1093/ije/dyh338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fritzell J, Nermo M, Lundberg O. The impact of income: assessing the relationship between income and health in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2004;32:6–16. 10.1080/14034950310003971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rehkopf DH, Krieger N, Coull B et al. Biologic risk markers for coronary heart disease: nonlinear associations with income. Epidemiology 2010;21:38–46. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30b89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehkopf DH, Berkman LF, Coull B et al. The non-linear risk of mortality by income level in a healthy population: US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey mortality follow-up cohort, 1988–2001. BMC Public Health 2008;8:383 10.1186/1471-2458-8-383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmot M. The influence of income on health: views of an epidemiologist. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:31–46. 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brønnum-Hansen H, Baadsgaard M. Widening social inequality in life expectancy in Denmark. A register-based study on social composition and mortality trends for the Danish population . BMC Public Health 2012;12:994 10.1186/1471-2458-12-994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blakely T, Kawachi I, Atkinson J et al. Income and mortality: the shape of the association and confounding New Zealand Census-Mortality Study, 1981–1999. Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:874–83. 10.1093/ije/dyh156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piketty T. Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: The Belknapp Press of Harvard University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritzell J, Bäckman O, Ritakallio V-M. Income inequality and poverty: do the Nordic countries still constitute a family of their own? In: Kvist J, ed.. Changing social equality the Nordic welfare model in the 21st century . Bristol: Policy Press, 2012:165–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolan B, Salverda W, Checchi D et al. Changing inequalities and societal impacts in rich countries: thirty countries’ experiences. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.OECD. Divided we stand: why inequality keeps rising. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huisman M, Kunst AE, Andersen O et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality among elderly people in 11 European populations. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:468–75. 10.1136/jech.2003.010496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann R. Socioeconomic inequalities in old-age mortality: a comparison of Denmark and the USA. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1986–92. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deaton A. Health, inequality, and economic development. J Econ Literature 2003;41:113–58. 10.1257/.41.1.113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowd JB, Albright J, Raghunathan TE et al. Deeper and wider: income and mortality in the USA over three decades. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:183–8. 10.1093/ije/dyq189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kvist J, Fritzell J, Hvinden B et al. Equality and the Nordic welfare model: principles, pressures and perspectives. In: Kvist J, ed.. Changing social equality. The Nordic welfare model in the 21st century. Bristol: Policy Press, 2012:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen K, Davidsen M, Juel K et al. The divergent life-expectancy trends in Denmark and Sweden—and some potential explanations. In: Crimmins E, Preston S, Cohen B, eds. International differences in mortality at older ages: dimensions and sources. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2010:385–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.2015. Swedish Work and Mortality Database (HSIA/WMB): Centre for Health Equity Studies. http://www.chess.su.se/research/data-materials/the-swedish-work-and-mortality-database-hsia-wmb.

- 19.McCullagh P. Quasi-likelihood functions. Ann Stat 1983;11:59–67. 10.1214/aos/1176346056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eilers PH, Marx BD. Flexible smoothing with B-splines and penalties. Stat Sci 1996;11:89–102. 10.1214/ss/1038425655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pace M, Lanzieri G, Glickman M et al. Revision of the European Standard Population: report of Eurostat's task force. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013.

- 22.Backlund E, Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ. The shape of the relationship between income and mortality in the United States: evidence from the National longitudinal mortality study. Ann Epidemiol 1996;6:12–20. 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00090-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martelin T. Mortality by indicators of socioeconomic status among the Finnish elderly. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1257–78. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90190-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackenbach JP. The persistence of health inequalities in modern welfare states: the explanation of a paradox. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:761–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann R. Socioeconomic differences in old age mortality. Dordrecht: Springer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martikainen P, Mäkelä P, Peltonen R et al. Income differences in life expectancy: the changing contribution of harmful consumption of alcohol and smoking. Epidemiology 2014;25:182–90. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarkiainen L, Martikainen P, Laaksonen M. The changing relationship between income and mortality in Finland, 1988–2007. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:21–7. 10.1136/jech-2012-201097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofoss D, Dahl E, Elstad JI et al. Selection and mortality: a ten-year follow-up of income decile mortality in Norway. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:558–63. 10.1093/eurpub/cks126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martikainen P, Mäkelä P, Koskinen S et al. Income differences in mortality: a register-based follow-up study of three million men and women. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:1397–405. 10.1093/ije/30.6.1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martikainen P, Valkonen T, Moustgaard H. The effects of individual taxable income, household taxable income, and household disposable income on mortality in Finland, 1998–2004. Popul Stud (Camb) 2009;63:147–62. 10.1080/00324720902938416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynch J, Smith GD, Harper SA et al. Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1. A systematic review. Milbank Q 2004;82:5–99. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00302.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gravelle H. How much of the relation between population mortality and unequal distribution of income is a statistical artefact? BMJ 1998;316:382 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfson MC, Kaplan G, Lynch J et al. Relation between income inequality and mortality: empirical demonstration. West J Med 2000;172:22 10.1136/ewjm.172.1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010974supp_figures.pdf (395KB, pdf)