Abstract

Affective forecasting often drives decision making. Although affective forecasting research has often focused on identifying sources of error at the event level, the present investigation draws upon the ‘realistic paradigm’ in seeking to identify factors that similarly influence predicted and actual emotions, explaining their concordance across individuals. We hypothesized that the personality traits neuroticism and extraversion would account for variation in both predicted and actual emotional reactions to a wide array of stimuli and events (football games, an election, Valentine’s Day, birthdays, happy/sad film clips, and an intrusive interview). As hypothesized, individuals who were more introverted and neurotic anticipated, correctly, that they would experience relatively more unpleasant emotional reactions, and those who were more extraverted and less neurotic anticipated, correctly, that they would experience relatively more pleasant emotional reactions. Personality explained 30% of the concordance between predicted and actual emotional reactions. Findings suggest three purported personality processes implicated in affective forecasting, highlight the importance of individual-differences research in this domain, and call for more research on realistic affective forecasts.

Keywords: affective forecasting, personality, individual differences, decision making, judgment

When making decisions, people often engage in affective forecasting, the process of predicting how future events will influence their emotional well-being. People tend to make bad decisions when their affective forecasts are steeped in error, and good decisions when their forecasts are realistic (Dunn & Laham, 2006; Hsee & Zhang, 2010; Wilson & Gilbert, 2005). The social-cognitive error paradigm, popular in this domain of research, has focused on identifying factors that differentially influence predicted versus actual emotional reactions (Hoerger, Quirk, Lucas, & Carr, 2009, 2010; see also, Mathieu & Gosling, 2012), thus resulting in discrepancies or error. In contrast, the ‘realistic paradigm’ (Funder, 1995) seeks to identify factors that comparably explain both predicted and actual emotional reactions, accounting for any degree of congruence across individuals in terms of who predicts and experiences more positive or negative reactions. Identifying factors that account for realistic affective forecasting could help to foster a balanced understanding of strengths and weaknesses in affective forecasting.

This investigation provides an illustrative example of the realistic paradigm in affective forecasting research by examining the extent to which personality dually explains predicted and actual reactions to a range of life events and laboratory stimuli, contributing to their concordance. In particular, theoretical evidence (Gray, 1994; also Corr, 2004, 2008) and empirical findings (Canli et al., 2001; Costa & McCrae, 1980; Gross, Sutton, & Ketelaar, 1998; Hoerger & Quirk, 2010; Tellegen, 1985; Zelenski & Larsen, 2001) on dispositional emotionality suggest that individuals who are more extraverted and less neurotic tend to experience more pleasant emotional reactions. The present investigation builds on this body of literature by examining whether neuroticism and extraversion are also associated with predicted emotional reactions. If so, personality could account for some of the relative match across individuals’ predicted and actual reactions.

A Historical Perspective: The Error Paradigm as the Prevailing Zeitgeist

Judgment research has traditionally drawn from two complementary perspectives, the realistic paradigm and the error paradigm (for reviews, see Funder, 1987, 1995, 2012). In the first half of the 20th century, this research was dominated by the realistic paradigm, which emphasizes the ways in which judgments are ‘good,’ defined as concordant across raters, stable, beneficial, or predictive of later behavior (e.g., Dymond, 1949; Taft, 1955; Vernon, 1933). With the rise of social and cognitive psychology in the 1980s, the error paradigm gained prominence (Funder, 1995, 2012; Swann & Seyle, 2005), emphasizing the ways in which judgments are ‘bad,’ or discordant from objective measurements, informant reports, actuarial data, or optimal reasoning. The prevailing focus on error is readily apparent in the emerging field of research on affective forecasting. For example, consistent with the error paradigm, 66% of articles in two recent meta-analyses (Levine, Lench, Kaplan, & Safer, 2012; Mathieu & Gosling, 2012) had titles that described affective forecasting using explicitly negative terms (e.g., error, bias, failure, ignorance, and emotional innumeracy1); no title described affective forecasting positively.

Affective forecasting studies have proceeded at two different levels of abstraction, increasingly shifting from descriptive to mechanistic research. Namely, descriptive studies have focused on the general level of the emotional event, aiming to identify whether forecasts are generally realistic versus error-prone. The central conclusions have been that affective forecasts can be prone to biases toward overestimating or underestimating the emotional intensity of future events (Wilson & Gilbert, 2013), and simultaneously, rank-order concordance is often moderate to high (rs from .30 to .50; Mathieu & Gosling, 2012), meaning that people can to some extent realistically gauge whether their emotional reactions will be more or less intense than the reactions of other individuals. Studies have moved toward the more specific question of what mechanisms – situational or individual-difference factors – influence predicted and actual emotional reactions.

Examples of mechanistic research from both the realistic and error paradigms across three common domains of judgment are provided in Table 1. In each domain, error research seeks to identify mechanisms that differentially affect predicted versus actual outcomes. In the affective forecasting domain, for example, emotional regulation strategies can affect actual emotional reactions considerably but bear little on emotional predictions, resulting in error (Dillard et al., 2010; Gilbert et al., 1998; Hoerger, 2012). Relatedly, an attentional bias called focalism, which leads people to focus on the most salient feature of an event, can affect predicted emotional reactions considerably but in some studies has been found to play less of a role in actual reactions, also resulting in error (Hoerger et al., 2009, 2010; Lench, Safer, & Levine, 2011; Wilson et al., 2000). These examples, focused on explaining differential variance in predicted versus actual reactions, contrast with research from the realistic paradigm seeking to identify mechanisms that explain substantive variance in both predicted and actual ratings simultaneously. For example, in the context of weather forecasting (see Table 1), geographic elevation affects regional variation in temperature, and because this information is widely documented, geographic elevation similarly affects weather forecasts, contributing toward them being realistic. Analogously, in the affective forecasting domain, some factors such as personality that shape actual emotional reactions might also underlie emotional predictions, contributing to realistic affective forecasting in terms of the relative positivity or negativity of reactions across individuals. Any particular forecast is likely multidetermined by a combination of concordance-enabling mechanisms that foster realistic forecasts and discordance-enabling mechanisms that that foster erroneous forecasts. Although recent trends in psychology have favored error research, understanding both realistic and error mechanisms is needed as these two complementary perspectives seek to answer different questions about the nature of judgment, such as understanding strengths versus weaknesses.

Table 1.

Hypothetical Examples of the Error Paradigm and Realistic Paradigm in Three Forecasting Contexts

| Paradigm | Weather Forecasting | Political Forecasting | Affective Forecasting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error Paradigm |

Goal: Identify sources of bias in weather forecasts |

Goal: Identify sources of bias in political polls (forecasts) |

Goal: Identify sources of bias in emotional predictions |

| Examples: Wet bias (overprediction of rain), Climate bias (ignoring secular changes in climate) |

Examples: Landline bias (conservative bias in polling only landline phones), Organizational bias (bias favoring the polling organizations’ views) |

Examples: Immune neglect (bias toward overlooking coping strategies), Focalism (bias toward ignoring non-central life events) |

|

| Realistic Paradigm |

Goal: Identify factors influencing both weather forecasts and observed weather, leading them to match |

Goal: Identify factors influencing both election polls as well as election results, leading them to match |

Goal: Identify factors influencing both predicted and actual emotional reactions, leading them to match in terms of relative ordering across individuals |

| Examples: Geographic latitude, geographic elevation, season | Examples: Incumbency status, state of the economy | Examples: Neuroticism, extraversion | |

Personality and Affective Forecasting Accuracy

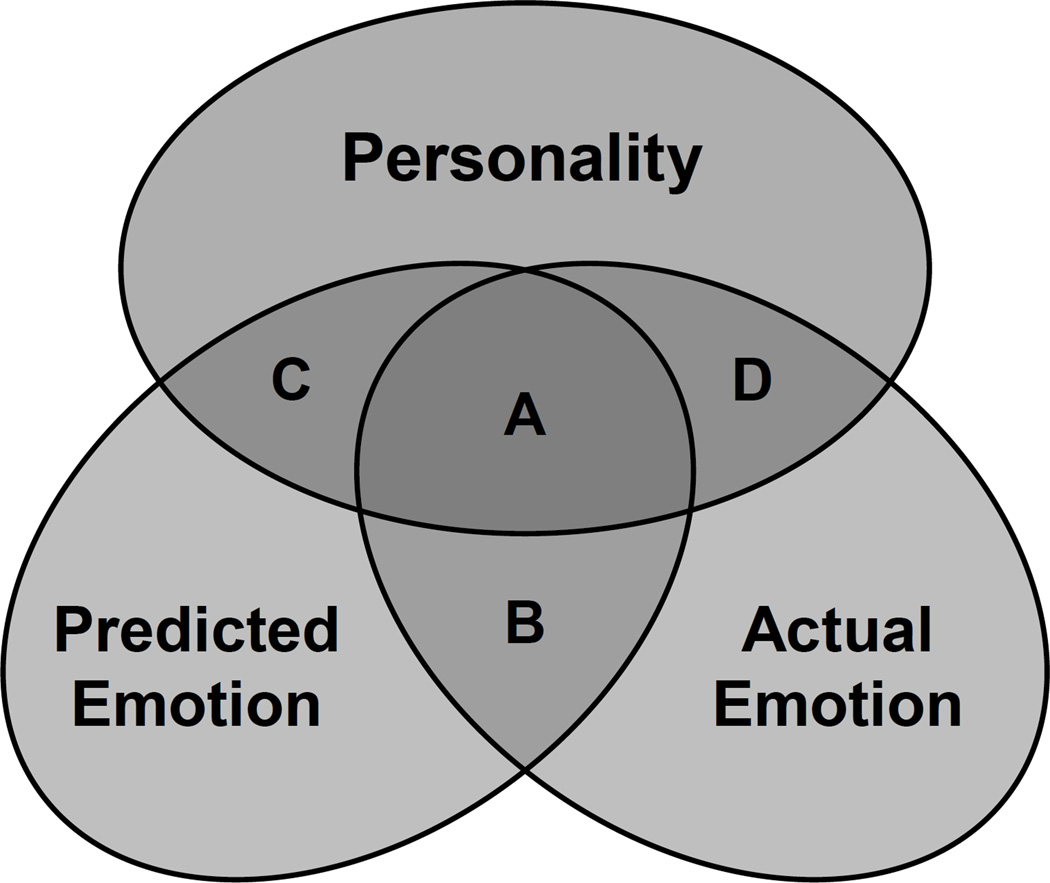

The realistic paradigm suggests new avenues for incorporating personality research into studies on affective forecasting. We begin by outlining how personality could logically and statistically explain concordance. Consider Figure 1. In this Venn diagram, predicted emotional reactions are realistic to the extent that they overlap with actual emotional reactions (Sections A and B), suggesting relative consistency across individuals in terms of who predicts and experiences more positive or negative reactions. Personality could contribute to realistic affective forecasting in two ways. For one, personality could account for a portion of the shared variance in predicted and actual emotional reactions (Section A), reflecting a general ‘dispositional emotionality’ that influences both predicted and actual emotional reactions to events or stimuli. Some theoretical evidence suggesting a broad role of personality in anticipation, approach motivation, and emotional response is consistent with this view (Corr, 2004, 2008; Gray, 1994; Hoerger & Quirk, 2010; Quirk, Subramanian, &Hoerger, 2007). As well, personality could simultaneously explain variance in predicted and actual reactions through two other distinct channels, one involving ‘prospection,’ the capacity to imagine one’s future (see Figure 1C), and another involving ‘experiential awareness’ related to contemplating one’s subjective experience (see Figure 1D). For example, some theorizing has emphasized the ways in which these two processes fundamentally differ (e.g., Dunn, Forrin, & Ashton-James, 2009; McConnell et al., 2011; Robinson & Clore, 2002), suggesting that different elements of personality might be involved in prospection versus emotional awareness.

Figure 1.

Personality and Realistic Affective Forecasting. Personality could account for realistic affective forecasting in terms of the relative ordering of positive to negative predicted and actual reactions across individuals. Namely, personality could explain common variance in both predicted and actual emotions (Section A), and simultaneously explain unique variance in predicted emotions (Section C) and actual emotions (Section D).

Prior research has provided robust evidence for the relationship between emotions and particular personality traits, especially neuroticism and extraversion. In particular, higher extraversion and lower neuroticism are associated with more pleasant actual emotional reactions to stimuli and life events (Canli et al., 2001; Costa & McCrae, 1980; Gross et al., 1998; Mroczek & Almeida, 2004; Nettle, 2006; Tellegen, 1985; Zelenski & Larsen, 2001). Although those studies have documented the overlap between personality and actual emotions using experimental (Canli et al., 2001; Gross et al., 1998; Zelenski & Larsen, 2001) or longitudinal (Costa & McCrae, 1980; Mroczek & Almeida, 2004; Tellegen, 1985) designs, none examined predicted emotional reactions to upcoming events or stimuli.

To our knowledge, only three studies have directly examined the relationship between personality traits and both predicted and actual reactions. In one study (Hoerger & Quirk, 2010), U.S. undergraduate participants completed an IPIP measure (Goldberg, 1999) of the Big 5 personality traits – neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness – and reported predicted and actual emotional reactions to Valentine’s Day. Higher extraversion and lower neuroticism were associated with more pleasant predicted and actual emotional reactions, though that study did not partition variance in order to determine whether personality contributed to realistic forecasts via a general ‘dispositional emotionality’ (see Figure 1A), separate processes involving ‘prospection’ (see Figure 1C) and ‘experiential awareness,’ (see Figure 1D), or all three. In a second study (Zelenski et al., 2013), U.S. undergraduates completed a brief adjective-based measure of extraversion (Saucier, 1994) and reported predicted and actual reactions to small-group activities in the lab, such as engaging in small talk or completing puzzles. As in Hoerger and Quirk (2010), they found that extraversion was associated with more pleasant predicted reactions. Surprisingly, personality was not related to actual reactions to their lab tasks, contrary to much of the personality-emotion literature (e.g., Canli et al., 2001; Zelenski & Larsen, 2001). In a third study (Quoidbach & Dunn, 2010), Belgian adults completed a neuroticism scale from the Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999) and an optimism measure (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994), and then reported predicted and actual reactions to President Obama’s electoral victory. No relationship between personality and predicted reactions was found, though it was unclear whether the context – Belgian’s reactions to U.S. politics – was evocative and representative. Nonetheless, personality was related to actual emotional reactions, reflecting its role in contemplating and reporting on subjective experience (see Figure 1D). In summary, some research suggests that higher extraversion and lower neuroticism may be related to more pleasant predicted and actual emotional reactions, though prior findings have been mixed, potentially affected by methodologic limitations, and have not distinguished dispositional emotionality from prospection and experiential awareness (see Figure 1).

Present Investigation

In the present investigation, we examined the role of personality in affective forecasting across a range of emotionally evocative stimuli and events. This included primary analyses of new and existing data on affective forecasting for football games, an election, Valentine’s Day, birthdays, happy and sad film clips, and an intrusive interview. Our primary aim was to examine whether personality was associated with both predicted and actual emotional reactions. Consistent with prior research (Canli et al., 2001; Mellers & McGraw, 2001; Nettle, 2006; Smits & Boeck, 2006; Zelenski & Larsen, 2001), we hypothesized that higher extraversion and lower neuroticism would be associated with more pleasant predicted and actual emotional reactions to these stimuli and events. Heterogeneity analyses examined whether effect sizes varied for neuroticism vs. extraversion. As well, prior research has found, albeit inconsistently, that findings can vary across the item content of personality surveys as well as for positive versus negative affect ratings (Corr, 2004; Grucza & Goldberg, 2007). Thus, we also dichotomized personality items as more or less relevant for affective forecasting (described in Methods) to explore the influence of item content, and we conducted another set of heterogeneity analyses to explore whether forecasts of negative affect and positive affect are equally influenced by personality. Our secondary aim was to examine whether personality accounted for shared variance in predicted and actual emotional reactions (see Figure 1A), unique variance in predicted emotions and unique variance in actual emotions (see Figure 1, C and D), or some combination of each.

Method

The investigation involved five samples of participants (N = 713). The studies included four real-world emotional events (Samples 1–4) and three emotionally evocative stimuli (Sample 5). The events and stimuli were intended to be relevant to the participants in these studies and vary in affective valence. Some studies focused on immediate emotional reactions, while others focused on the potentially more challenging task (Finkenauer et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2000) of predicting how one would feel days or weeks after a target event occurred. The studies also varied along a number of contextual dimensions (e.g., personal vs. societal relevance, field vs. lab setting), allowing us to examine the effects of personality across scenarios. The former three samples involved primary analyses of existing data (Hoerger et al., 2009, 2010; Hoerger, Quirk, Chapman, & Duberstein, 2012), and the latter two involved new data collection. The studies included measures of extraversion (Samples 3), neuroticism (Sample 5), or both (Sample 1, 2, and 4).

Sample 1: Football Game

Participants and Procedures

Sample 1 (Hoerger et al., 2009) involved 180 students (67% women; mean age = 19.6 years, SD = 2.7 years) at Michigan State University (MSU). Participants completed a personality measure at baseline and then provided predicted happiness ratings for one of nine home team college football games. At follow-up, they provided actual happiness ratings for the corresponding game. Half of participants happened to experience a winning game, and half a loss. All football games were held on Saturdays.

Emotion Ratings

Three days prior to the game, participants predicted how happy they would feel the following Monday both in the event of a win and a loss (predicted ratings for the game outcome that did not occur were discarded). Then, on the following Monday, they reported their actual current happiness. Predicted and actual emotion ratings were made on a 9-point happiness scale used in prior forecasting studies (Gilbert et al., 1998).

Personality

Participants completed 10-item IPIP (Goldberg, 1999) measures of Neuroticism (α = .87, e.g., “I often feel blue”) and Extraversion (α = .84, e.g., “I look at the bright side of life”). The IPIP scales have shown evidence for reliability and convergent validity with other personality measures (Goldberg, 1999).

Sample 2: Election

Participants and Procedures

Sample 2 (Hoerger et al., 2010) involved 57 MSU students (68% women; mean age = 19.5 years, SD = 1.3 years). At baseline, they completed a personality measure and provided predicted happiness ratings for the 2004 U.S. Presidential election; 65% of participants supported John Kerry and 35% supported George W. Bush. At follow-up after the election, participants reported their actual happiness.

Emotion Ratings

In the two months leading up to the election, participants predicted how happy they would feel two weeks after the election, both in the event Bush won and Kerry won (predicted ratings for a Kerry win were discarded). Two weeks after the election, they reported on their actual current level of happiness. Emotion ratings were made using the same 9-point happiness scale as in Sample 1.

Personality

Neuroticism (α = .86) and Extraversion (α = .85) were assessed using the same scales as in Sample 1.

Sample 3: Valentine’s Day

Participants and Procedures

Sample 3 (Hoerger, Quirk et al., 2012) included 325 students (80% women; mean age = 19.8 years, SD = 2.1 years) at Central Michigan University (CMU) studied in 2007. Methods were similar to the 2006 Valentine’s Day study noted previously (Hoerger & Quirk, 2010). In January, participants completed a personality measure and predicted their reactions to Valentine’s Day and each of two subsequent days (2/14, 2/15, and 2/16). In February they provided actual ratings of current emotions on each of those three days.

Emotion Ratings

Using 9-point rating scales, predicted and actual emotional reactions were rated along six dimensions: happiness, pleasure, joy, sadness, gloom, and misery. Negative affects were reverse coded, and ratings were averaged across emotions and days (2/14, 2/15, and 2/16) to yield composite indicators of predicted and actual reactions (average α = .91).

Personality

As a proxy measure of Extraversion, we analyzed data from the 18-item TEPS (α = .85, Gard, Gard, Kring, & John, 2006), which assesses trait differences in positive emotionality (e.g., “When something exciting is coming up in my life, I really look forward to it”). The TEPS is a valid proxy as it has been shown in diverse samples to be associated with several de facto indicators of extraversion, such as positive affectivity, interpersonal involvement, activation, and approach motivation (Buck & Lysaker, 2013; Ho, Cooper, Hall, & Smillie, in press; Liu et al., 2012). No measure of neuroticism was included in the study.

Sample 4: Birthdays

Participants and Procedures

Participants (n = 55) were CMU students (76% female, mean age = 20.5 years, SD = 3.3), who were selected to have birthdays between late October and early December. At the start of the fall semester, participants predicted how they would feel the day after their birthday. Then, the day after their birthday, they reported their current emotional state and completed the personality measure. We focused on the day after birthdays, rather than birthdays themselves, to increase the challenge of the task as well as avoid potential pitfalls, such as some participants reporting actual reactions before their birthday had fully unfolded.

Emotion Ratings

Using 5-point rating scales, predicted and actual emotional reactions were rated along four dimensions: happiness, satisfaction, sadness, and disappointment. Negative affects were reverse coded and ratings averaged to yield composite indicators of predicted and actual reactions (average α = .80).

Personality

Extraversion was assessed using the 6-item sociability subscale (α = .69, e.g., “I can deal effectively with people”) from the TEIQue-SF (Petrides & Furnham, 2006), and Neuroticism was assessed using the 6-item emotional well-being scale (α = .88, e.g., “On the whole, I have a gloomy perspective on most things”) from the same instrument. The scales have been found to correlate with other measures of extraversion and neuroticism in large, diverse samples (Petrides et al., 2010; Siegling, Saklofske, Vesely, & Nordstokke, 2012).

Sample 5: Emotional Stimuli

Overview

In contrast to the prior studies involving real-world emotional events, participants in this sample were exposed to emotionally evocative stimuli designed to trigger three broad domains of emotion: happiness, sadness, and anxiety. Brief film clips are commonly used to evoke happiness and sadness (Gruber, Oveis, Keltner, & Johnson, 2008; Morrone-Strupinsky & Depue, 2004). Anxiety is often triggered through interpersonal encounters; for example, several studies have used an intrusive interview of highly personal questions to evoke anxiety (see Shean & Wais, 2000). In each of those studies, personality was associated with emotional reactivity, making the stimuli appropriate for the current investigation.

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 96 CMU students (67% women; mean age = 18.6 years, SD = 1.5 years). They provided predicted and actual reactions to emotionally-evocative laboratory stimuli, which included two film clips and an intrusive interview. At baseline, participants completed a web-based survey. This involved predicting their emotional reactions to each film clip based on descriptive narratives (119–153 words), predicting their reactions to an intrusive interview based on the interview questions, and completing personality measures. Approximately two months later, they attended a lab session where they experienced each of the stimuli and reported their actual emotional reactions.

Stimuli

The film clips, five minutes each, included college antics in Old School (happy film clip) and a funeral scene from Garden State (sad film clip). These specific film clips were chosen based on pilot testing demonstrating that they triggered the intended emotional response. The intrusive interview consisted of eight highly personal questions (e.g., “How do you react to criticism and praise by others and what are you criticized and praised for?”), which were designed to evoke temporary feelings of anxiety (for a review of this interview protocol, see Shean & Wais, 2000). Actual emotional reactions were reported immediately after each of these three stimuli. The film clips were presented in counterbalanced order on a 15-inch PC monitor, followed by the interview. As a series of emotionally evocative stimuli were used, we followed existing recommendations (Rottenberg, Ray, & Gross, 2007) to include neutral stimuli –specifically, five-minute film clips depicting nature scenes – immediately prior to the latter two emotionally evocative stimuli. This reduces the risk that contrast effects could bias ratings.

Emotion Ratings

Predicted and actual emotional reactions were assessed using three self-report methods common for triangulating emotional response (Larsen & Prizmic-Larsen, 2006): subjective emotion ratings (like those used in Samples 1–4), behavioral tendency ratings that indicate actions or urges relevant to emotion, and open-ended responses quantitatively coded by raters. In terms of open-ended responses, participants described predicted and actual reactions to each stimulus, e.g., “I would feel very sad and upset” (M = 16.2, SD = 11.4 words per response). Six psychology graduate students coded these responses using a 9-point emotion rating scale. Interrater reliability was excellent across 3,456 ratings (96 participants x 6 ratings x 6 raters), with an average measures intraclass correlation (ICC) of .97. Participants also rated predicted and actual reactions via four context-specific ratings of behavioral tendencies indicative of emotion (e.g., “wanting to cry,” “wanting to throw something out of frustration”); the specific item wording was customized for each stimulus, based on prior pilot testing, and participants responded using a 9-point rating scale. Finally, participants reported predicted and actual reactions for each stimulus by rating four subjective emotions (e.g., happiness, sadness), using a 9-point rating scale; the specific emotion words were customized by stimulus based on prior pilot testing. The behavioral tendency and subjective rating scales both demonstrated good internal consistency (average α = .81). The three types of emotion ratings demonstrated excellent convergent validity with an average intercorrelation of r = .58. Accordingly, they were averaged to yield composite indicators of predicted reactions and actual reactions for each of the three stimuli (average α = .78); higher scores were coded to reflect more pleasant (or less unpleasant) reactions.

Personality

Participants also completed 28 items assessing several indicators of Neuroticism (α = .93). The measure included the same 10-item IPIP measure from Studies 1 and 2 (Goldberg, 1999), as well as several related indicators, including a 9-item measure of trait social anxiety (e.g., “I sometimes avoid going to places where there will be many people because I will get anxious,” Raine, 1991), a 5-item measure of negative affect intensity (e.g., “I get upset easily,” Larsen, & Diener, 1987), and a 4-item measure of positive-affect shame (e.g., “Expressing enjoyment about a fun activity you’re engaged in makes you a bad person,” Kaufman, 2004). These scales have shown evidence for reliability and validity in prior studies examining their relationships with other measures of neuroticism (e.g., Goldberg, 1999, Völter et al., 2011; Williams, 1989). No measure of extraversion was included in the study.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the extent to which affective forecasts were realistic or error-prone at the event-level in each sample. Following prior procedures (Mathieu & Gosling, 2012), the zero-order correlation (r) between predicted and actual emotion ratings was used to gauge whether participants were realistic in terms of the relative order of who had the most positive to most negative reactions. The average absolute deviation (|Mpredicted-Mactual|/SDactual) between predicted and actual reactions was used as an omnibus indicator of overall error (e.g., Dunn, Brackett, Ashton-James, Schneiderman, & Salovey, 2007; Hoerger, Chapman, Epstein, & Duberstein, 2012), which represents the average number of standard deviations that predicted emotion ratings erred from actual emotion ratings. Effects were averaged within sample (for Sample 5) and then averaged across samples, weighted by sample size.

Our primary aim was evaluated by examining the extent that personality correlated with predicted and actual emotional reactions. All correlations were in the expected direction (positive for extraversion, negative for neuroticism), so in conducting meta-analyses, R-values were used to reflect the magnitude of the effect. In Samples 1, 2, and 4, the multiple R was used to account for the fact that both neuroticism and extraversion were measured in each sample. Weighted averages were computed, first averaging within Sample 5 and then averaging across studies. Steiger’s Z-test for dependent correlations was used to examine whether personality correlated differentially with predicted versus actual emotional reactions, and given the large sample size (N = 713), the study was powered to detect correlations that differed by as little as .07 in the overall meta-analysis. In the event of a significant Q statistic, we planned to conduct three sets of heterogeneity analyses. These included examining the magnitude of findings across positive versus negative affect ratings (only Samples 3–5 included both), neuroticism vs. extraversion, and variation in findings across specific personality items. Personality items were classified as more conceptually relevant to affective forecasting (i.e., those mentioning feeling words or the future, 43 items, such as “I get upset easily” and “I get anxious when meeting people for the first time”) or less conceptually relevant to affective forecasting (25 items, such as “I believe I’m full of personal strengths” and “I would describe myself as a good negotiator”) by two raters (93% agreement, κ = .85), with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Our secondary aim was evaluated using a series of hierarchical regression analyses (for examples, see Seibold & McPhee, 1979; Zientek & Thompson, 2006). Within each sample, we computed 5 variance estimates: the total variance in predicted emotions explained by personality (Figure 1, Sections A+C), the total variance in actual emotions explained by personality (Sections A+D), the total incremental variance in predicted emotions explained by personality over and above that accounted for by actual emotions (Section C), the total incremental variance in actual emotions explained by personality over and above that accounted for by predicted emotions (Section D), and the total common variance (Section A), computed by subtracting the fourth variance estimate (Section D) from the second estimate (Sections A+D). F-tests were used to evaluate statistical significance, and findings were summarized with weighted-averages.

Results

Descriptive Overview

The descriptive analyses provide evidence for the ways in which affective forecasting is realistic across individuals and error-prone at the event-level. On average, predicted emotional reactions deviated from actual emotional reactions by 0.88 SD units, p < .001 (see Table 2), ranging from 0.67 to 1.22 SD units. At the same time, predicted and actual emotional reactions correlated r = .52, p < .001, ranging from r = .31 to .65, and suggesting some relative consistency across individuals. Both the correlations and estimates of error were statistically significant across all samples and stimuli. In summary, predicted and actual emotional reactions differ from perfect concordance, but are also significantly correlated.

Table 2.

Personality, Predicted Emotional Reactions, and Actual Emotional Reactions

| Concordance Between Predicted and Actual Emotions |

Personality Correlates of Predicted and Actual Emotions |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Emotional Stimulus/Event |

N | Dm | r | Personality Trait(s) |

Predicted r |

Actual r |

| 1 | Football Game | 180 | 1.22*** | .31*** | Extraversion | .37*** | .20** |

| Neuroticism | −.11 | −.23** | |||||

| 2 | Election | 57 | 1.02*** | .33** | Extraversion | .31* | .16 |

| Neuroticism | −.21 | −.09 | |||||

| 3 | Valentine’s Day | 325 | 0.75*** | .65*** | Extraversion | .30*** | .35*** |

| 4 | Birthday | 55 | 0.78** | .36** | Extraversion | .42** | .38** |

| Neuroticism | −.49*** | −.55*** | |||||

| 5.1 | Sad Film | 96 b | 0.69** | .64*** | Neuroticism | −.38*** | −.34*** |

| 5.2 | Happy Film | 96 | 0.67** | .51*** | Neuroticism | −.30** | −.40*** |

| 5.3 | Intrusive Interview | 96 | 0.70*** | .60*** | Neuroticism | −.51*** | −.48*** |

| Composite a | 713 | 0.88*** | .52*** | .36*** | .35*** | ||

Note. Dm = The average absolute deviation (|MpredictedMactual|/SDactual), or the average number of standard deviations that predicted emotion ratings erred from actual emotion ratings. r = the zero-order correlation between predicted emotion ratings and actual emotion ratings, reflecting the extent forecasts are realistic in terms of relative ordering across individuals. In all cases, higher values for predicted and actual emotion ratings reflect more pleasant emotions.

The composite is a weighted average. Effects were averaged within sample for Studies 5.1–5.3 and then averaged across Studies 1–5, weighted by sample size. For the composite values in the latter two columns, R-values were used in order to make all values positive (each effect was in the hypothesized direction), and in Studies 1, 2, and 4, multiple R was used to account for the combined effects of neuroticism and extraversion.

The same sample of participants completed Studies 5.1–5.3.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Aim 1: Personality Correlates of Predicted and Actual Emotions

Personality was hypothesized and found to correlate with both predicted and actual emotional reactions (see Table 2). Overall, personality correlated R = .36, p < .001, with predicted emotional reactions. As expected, extraversion was associated with more pleasant predicted emotional reactions, and neuroticism was associated with more unpleasant predicted emotional reactions. The magnitude of the effect varied from |r| = .11 to .51. Overall, personality correlated comparably with actual emotional reactions, R = .35, p < .001. Again, extraversion was associated with more pleasant actual reactions, and neuroticism with more unpleasant reactions. The magnitude of this effect ranged from |r| = .09 to .55. As well, the correlations between personality and predicted emotions (|r| = .33 to .40) and actual emotions (|r| = .29 to .41) were comparable across the varying methodologies employed in Sample 5.

For the composite estimate, personality was similarly associated with predicted and actual emotional reactions, Steiger’s Z = 0.30, p = .77. Although Steiger’s Z was also non-significant in each sample, there was significant variability in the magnitude of the difference between correlations for predicted versus actual reactions (Q = 32.46, p < .001). However, the planned heterogeneity analyses did not account for this cross-study variability. Specifically, personality-affect correlations were comparable for extraversion (predicted |r| = .33, actual |r| = .31, Z = 0.54, p = .59) and neuroticism (predicted |r| = .25, actual |r| = .28, Z = 0.63, p = .53). Consistent with that finding, individual personality items correlated similarly with predicted and actual emotional reactions regardless of whether the items were defined a priori as more relevant to affective forecasting (predicted |r| = .18, actual |r| = .19, Z = −0.28, p = .78) or less relevant (predicted |r| = .18, actual |r| = .18, Z = 0.14, p = .89). Moreover, personality scale scores correlated comparably with predicted and actual ratings for both positive (predicted |r| = .32, actual |r| = .35, Z = −0.72, p = .47) and negative (predicted |r| = .29, actual |r| = .32, Z = −0.79, p = .43) affects.

Aim 2: Hierarchical Analyses of Total, Unique, and Shared Variance

Hierarchical analyses showed that personality accounted for shared and unique variance in predicted and actual emotional reactions (see Table 3). In particular, neuroticism and extraversion explained 8% of the overlapping variance shared by predicted and actual emotional reactions (equivalent to Figure 1, Section A), an additional 5% of unique variance in predicted emotional reactions (equivalent to Figure 1, Section C), and an additional 4% of unique variance in actual emotional reactions (equivalent to Figure 1, Section D). This means that some personality processes directly account for the predicted-actual reaction link, whereas other aspects of personality had small independent effects on predicted or actual reactions. Each of these variance estimates differed across samples and stimuli, including within-subject in Sample 5 (see Table 3). Given the average correlation between predicted and actual emotions (r = .52, or R2 = .27), neuroticism and extraversion can be estimated to explain 30% of the direct correspondence, or relative consistency across individuals, between predicted and actual emotions (.08 / .27 = 30%).

Table 3.

Personality is Associated with Total, Unique, and Shared Variance in Predicted and Actual Emotional Reactions

| Venn Diagram Section c |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A+C | A+D | C | D | A | |||

| Study | Emotional Stimulus/Event |

N | Total Variance in Predicted Emotions Explained by Personality |

Total Variance in Actual Emotions Explained by Personality |

Unique Variance in Predicted Emotions Explained by Personality |

Unique Variance in Actual Emotions Explained by Personality |

Shared Variance in Predicted and Actual Emotions Explained by Personality |

| 1 | Football Game | 180 | .15*** | .06** | .11*** | .04* | .02 |

| 2 | Election | 57 | .10* | .03 | .07* | .00 | .03 |

| 3 | Valentine’s Day | 325 | .09*** | .12*** | .00 | .03** | .09*** |

| 4 | Birthday | 55 | .25*** | .30*** | .12* | .17** | .13** |

| 5.1 | Sad Film | 96 b | .14** | .19*** | .00 | .05* | .14** |

| 5.2 | Happy Film | 96 | .09*** | .16*** | .01 | .08** | .08** |

| 5.3 | Intrusive Interview | 96 | .26*** | .23*** | .07** | .04* | .19*** |

| Composite a | 713 | .13*** | .12*** | .05*** | .04*** | .08*** | |

Note.

The composite is a weighted average. Effects were averaged within sample for Studies 5.1–5.3 and then averaged across Studies 1–5, weighted by sample size.

The same sample of participants completed Studies 5.1–5.3.

See Figure 1 for a visual representation of each column.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Discussion

Personality was hypothesized and found to explain both predicted and actual emotional reactions to seven emotionally evocative stimuli and events, consistent with prior research (Canli et al., 2001; Mellers & McGraw, 2001; Smits & Boeck, 2006; Zelenski & Larsen, 2001) and theory (Corr, 2008; Funder, 2005; Gray, 1994; Robinson & Clore, 2002). In particular, individuals who were more introverted and neurotic were realistic in predicting that they would experience more unpleasant emotional reactions than their peers in response to these stimuli and events. Individuals who were more extraverted and less neurotic were realistic in predicting that they would experience more pleasant emotional reactions, relative to their peers. Personality accounted for realistic affective forecasting by explaining shared variance in predicted and actual emotional reactions (see Figure 1A), and by simultaneously accounting for unique variance in both predicted and actual emotions (see Figure 1C–D). These data have potential implications for theory and future research on realistic affective forecasting.

The present investigation highlights the importance of individual-differences research aimed at understanding realistic affective forecasting. Many forecasting studies have focused of describing errors at the general event-level (see Wilson & Gilbert, 2013), and studies aimed at identifying mechanisms have often focused on contextual factors accounting for error, such as situational features affecting attentional focus (Lench et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2000), social processes that facilitate rationalization (Gilbert et al., 1998), or culture (Lam et al., 2005). The few individual-difference studies have also mainly focused on explaining errors (Dunn et al., 2007; Hoerger, 2012; Hoerger, Chapman et al., 2012; Quoidbach & Dunn, 2010; Zelenski et al., 2013). In building on prior empirical findings (e.g., Canli et al., 2001; Zelenski & Larsen, 2001), our results make a theoretical contribution by showing that the traits extraversion and neuroticism are intricately related not just to the experience of emotion, but to the relative concordance between experienced and anticipated emotion. Consistent with prior theorizing, a single underlying personality process could account for shared variance in motivation, predicted emotions, and actual emotions, facilitating realistic affective forecasting and decision making (Corr, 2004, 2008; Hoerger & Quirk, 2010; Hoerger et al., 2007). In our investigation, neuroticism and extraversion explained about 30% of the direct link between predicted and actual reactions (see Figure 1A), suggestive of a single underlying process. What is this single process? It may reflect a very general dispositional emotionality, simultaneously related to actual emotions, predicted emotions, and perhaps other types of emotional reports (i.e., recollected, hypothetical). Yet, that single putative process only tells a partial story.

Two auxiliary processes contributing to realistic forecasting can be inferred from our data. In particular, we found that personality accounted for unique variance in predicted reactions (5%; see Figure 1C) and in actual reactions (4%; see Figure 1D). These findings lead us to speculate that two other personality processes, one related to prospection (projecting into the future) and one related to experiential awareness, are comparable in magnitude and may act in concert to facilitate realistic affective forecasts, in terms of the relative ordering of positive to negative reactions across individuals. This speculation is consistent with theories emphasizing that these two processes fundamentally differ (Dunn et al., 2009; McConnell et al., 2011; Robinson & Clore, 2002). In summary, our findings suggest that personality generally contributes to realistic affective forecasting in terms of who predicts and experiences more positive or negative emotional reactions, and our analyses lead us to hypothesize three personality processes underlying congruence: dispositional emotionality, prospection, and experiential awareness.

The ideas presented here suggest new avenues for research on affective forecasting drawing from the realistic paradigm. Namely, the present findings suggest the need to identify factors that simultaneously influence predicted and actual emotional reactions. As neuroticism and extraversion explained about 30% of the correspondence between predicted and actual reactions, there is room for future research to examine other individual-difference constructs that may account for additional variance in affective forecasting congruence. As our heterogeneity analyses were unable to account for variability in observed effects, future studies could build on our findings by attempting to elucidate the personality-related psychological processes that may account for shared or unique variance in predicted and actual emotions.

The present research was balanced by several strengths and weaknesses. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to replicate a finding on individual differences in affective forecasting across such a wide array of emotional evocative stimuli and events. Other strengths included the relatively large sample size, the diversity of the study procedures, and the potential theoretical contribution of this research. However, the study samples were homogenous, consisting of young adult college students. Future studies aimed at understanding emotional processes and their role in decision making in samples more representative of the U.S. population could make an important contribution (Croyle, 2015).

Moreover, our findings are based on the aggregate of five specific studies. Point estimates for the personality-emotion link varied across studies (see Table 2), with stronger relationships observed for birthdays and the intrusive interview than for the election. The overall findings also differed from two prior reports, which found that personality was only related to predicted reactions (Zelenski et al., 2013) or only related to actual reactions (Quoidbach & Dunn, 2010). These differences could be due to the different types of stimuli (e.g., events that vary in valence or personal relevance, laboratory stimuli), differences in measurement (e.g., personality scales, emotion scales), or differences in the time span between predictions and the emotional event. Thus, more research is needed to account for cross-study variation in affective forecasting research.

Finally, future research seeking to demonstrate that affective forecasting research can improve decision making would be particularly timely. A number of studies have shown that affective forecasting is correlated with decision making (see Hoerger, Chapman et al., 2012), and shown that experimental manipulations of affective forecasting can augment decisions made by research participants in structured laboratory settings (see Gilbert et al., 2009). Research on health decision making is a growing national priority in the U.S. (PCORI, 2012), but few studies have examined whether affective forecasting interventions can improve decisions of broad societal significance, such as engagement in exercise (Ruby et al., 2011) and participation in cancer screenings (Dillard et al., 2010). Thus, more research is needed from both the realistic paradigm and error paradigm examining whether findings on affective forecasting can ultimately benefit significant real-world decisions.

In conclusion, we found that neuroticism and extraversion accounted for much of the relationship between predicted and actual emotional reactions. This investigation highlights the importance of individual-differences research in this domain and makes a theoretical contribution to emotion research by suggesting that traits contribute to realistic affective forecasting, namely the relative ordering of predicted and actual emotional reactions across individuals, through three putative processes: dispositional emotionality, prospection, and experiential awareness.

Acknowledgments

Funding Note

This work was supported by T32MH018911, K08AG031328, and U54GM104940 from the United States Department of Health and Human Services, and intramural grants from Michigan State University and Central Michigan University.

Footnotes

The exhaustive list of other error-focused terms includes the following: can’t predict, contrary to affective forecasts, do not anticipate, don’t learn, focalism, mispredict, misunderstand, more regret than imagined, neglect, unaware, and underestimating.

References

- Buck B, Lysaker PH. Consummatory and anticipatory anhedonia in schizophrenia: Stability, and associations with emotional distress and social function over six months. Psychiatry Research. 2013;205:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler R, McFarland C. Intensity bias in affective forecasting: The role of temporal focus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1480–1493. doi: 10.1177/0146167205274691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Zhao Z, Desmond JE, Kang E, Gross J, Gabrieli JDE. An fMRI study of personality influences on brain reactivity to emotional stimuli. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;115:33–42. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.115.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr PJ. Reinforcement sensitivity theory and personality. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr PJ. The reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality. Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:668–678. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croyle RT. Risks and opportunities for psychology’s contribution to the war on cancer. American Psychologist. 2015;70:221–224. doi: 10.1037/a0038869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard AJ, Fagerlin A, Dal Cin S, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Narratives that address affective forecasting errors reduce perceived barriers to colorectal cancer screening. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EW, Brackett MA, Ashton-James C, Schneiderman E, Salovey P. On emotionally intelligent time travel: Individual differences in affective forecasting ability. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:85–93. doi: 10.1177/0146167206294201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EW, Forrin ND, Ashton-James CE. On the excessive rationality of the emotional imagination: A two-systems account of affective forecasts and experiences. In: Markman KD, Klein WMP, Suhr JA, editors. Handbook of imagination and mental simulation. New York: Psychology Press; 2009. pp. 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EW, Laham SA. Affective forecasting: A user’s guide to emotional time travel. In: Forgas J, editor. Affect in social thinking and behavior. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2006. pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Dymond RF. A scale for the measurement of empathic ability. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1949;13:127–133. doi: 10.1037/h0061728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkenauer C, Gallucci M, van Dijk WW, Pollmann M. Investigating the role of time in affective forecasting: Temporal influences on forecasting accuracy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:1152–1166. doi: 10.1177/0146167207303021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder DC. Errors and mistakes: Evaluating the accuracy of social judgment. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:75–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder DC. On the accuracy of personality judgment: A realistic approach. Psychological Review. 1995;102:652–670. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder DC. Accurate personality judgment. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2012;21:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Gard MG, Kring AM, John OP. Anticipatory and consummatory components of the experience of pleasure: A scale development study. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:1086–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, Killingsworth MA, Eyre RN, Wilson TD. The surprising power of neighborly advice. Science. 2009;323:1617–1619. doi: 10.1126/science.1166632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, Pinel EC, Wilson TD, Blumberg SJ, Wheatley TP. Immune neglect: A source of durability bias in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:617–638. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: Mervielde I, Deary I, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. Personality Psychology in Europe. Vol. 7. Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press; 1999. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Personality dimensions and emotion systems. In: Ekman P, Davidson R, editors. The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 329–331. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Sutton SK, Ketelaar T. Affective-reactivity views. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Oveis C, Keltner D, Johnson SL. Risk for mania and positive emotional responding: Too much of a good thing? Emotion. 2008;8:23–33. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Goldberg LR. The comparative validity of 11 modern personality inventories: Predictions of behavioral acts, informant reports, and clinical indicators. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;89:167–187. doi: 10.1080/00223890701468568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PM, Cooper AJ, Hall PJ, Smillie LD. Factor structure and construct validity of the temporal experience of pleasure scales. Journal of Personality Assessment. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2014.940625. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M. Coping strategies and immune neglect in affective forecasting: Direct evidence and key moderators. Judgment and Decision Making. 2012;7:86–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M, Quirk SW. Affective forecasting and the Big Five. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;49:972–976. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M, Chapman B, Epstein RM, Duberstein PR. Emotional intelligence: A theoretical framework for individual differences in affective forecasting. Emotion. 2012;12:716–725. doi: 10.1037/a0026724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M, Epstein RM, Winters PC, Fiscella K, Duberstein PR, Gramling R, Kravitz RL. Values and Options in Cancer Care (VOICE): Study design and rationale for a patient-centered communication and decision-making intervention for physicians, patients with advanced cancer, and their caregivers. BMC Cancer. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M, Quirk SW, Chapman BP, Duberstein PR. Affective forecasting and self-rated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and hypomania: Evidence for a dysphoric forecasting bias. Cognition & Emotion. 2012;26:1098–1106. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.631985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M, Quirk SW, Lucas RE, Carr TH. Immune neglect in affective forecasting. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;43:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M, Quirk SW, Lucas RE, Carr TH. Cognitive determinants of affective forecasting errors. Judgment and Decision Making. 2010;5:365–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsee CK, Zhang J. General evaluability theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:343–355. doi: 10.1177/1745691610374586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 1999;2:102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman G. The psychology of shame: Theory and treatment of shame-based syndromes. second. New York: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lam KCH, Buehler R, McFarland C, Ross M, Cheung I. Cultural differences in affective forecasting: The role of focalism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:1296–1309. doi: 10.1177/0146167205274691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen R, Diener E. Affect intensity as an individual difference characteristic: A review. Journal of Research in Personality. 1987;21:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen R, Prizmic-Larsen Z. Measuring emotions: Implications of a multimethod perspective. In: Eid M, Diener E, editors. Handbook of Multimethod Measurement in Psychology. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 337–352. [Google Scholar]

- Lench HC, Safer MA, Levine LJ. Focalism and the underestimation of future emotion: When it’s worse than imagined. Emotion. 2011;11:278. doi: 10.1037/a0022792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine LJ, Lench HC, Kaplan RL, Safer MA. Accuracy and artifact: Reexamining the intensity bias in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;103:584–605. doi: 10.1037/a0029544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WH, Wang LZ, Zhu YH, Li MH, Chan RC. Clinical utility of the Snaith-Hamilton-Pleasure scale in the Chinese settings. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:184. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu MT, Gosling SD. The accuracy or inaccuracy of affective forecasts depends on how accuracy is indexed: A meta-analysis of past studies. Psychological Science. 2012;23:161–162. doi: 10.1177/0956797611427044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell AR, Dunn EW, Austin SN, Rawn CD. Blind spots in the search for happiness: Implicit attitudes and nonverbal leakage predict affective forecasting errors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2011;47:628–634. [Google Scholar]

- Meehl PE. The dynamics of structured personality tests. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1945;1:296–303. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200003)56:3<367::aid-jclp12>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellers BA, McGraw AP. Anticipated emotions as guides to choice. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:210–214. [Google Scholar]

- Micallef L, Rodgers P. Drawing area-proportional Venn-3 diagrams using ellipses; Presented at the annual meeting of the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing; Baltimore, MD. 2012. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Morrone-Strupinsky JV, Depue RA. Differential relation of two distinct, film-induced positive emotional states to affiliative and agentic extraversion. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36:1109–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Almeida DM. The effect of daily stress, personality, and age on daily negative affect. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:355–378. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettle D. The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. American Psychologist. 2006;61:622. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PCORI. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute: National priorities for research and research agenda. PCORI Board of Governor’s Meeting. 2012 doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. Retrieved from http://pcori.org/assets/PCORI-National-Priorities-and-Research-Agenda-2012-05-21-FINAL1.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Petrides KV, Furnham A. The role of trait emotional intelligence in a gender-specific model of organizational variables. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2006;36:552–569. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides KV, Vernon PA, Schermer JA, Ligthart L, Boomsma DI, Veselka L. Relationships between trait emotional intelligence and the Big Five in the Netherlands. Personality and Individual differences. 2010;48:906–910. [Google Scholar]

- Quirk SW, Subramanian L, Hoerger M. Effects of situational demand upon social enjoyment and preference in schizotypy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:624–631. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quoidbach J, Dunn EW. Personality neglect: The unforeseen impact of personal dispositions on emotional life. Psychological Science. 2010;21:1783–1786. doi: 10.1177/0956797610388816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. The Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ): A measure of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1991;17:555–564. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Clore GL. Belief and feeling: evidence for an accessibility model of emotional self-report. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:934–960. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Ray RD, Gross JJ. Emotion elicitation using films. In: Coan JA, Allen JJB, editors. The handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. London, England: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ruby MB, Dunn EW, Perrino A, Gillis R, Viel S. The invisible benefits of exercise. Health Psychology. 2011;30:67–74. doi: 10.1037/a0021859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucier G. Mini-Markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar Big-Five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1994;63:506–516. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16:201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Shean G, Wais A. Interpersonal behavior in schizotypy. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2000;188:842–846. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200012000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibold DR, McPhee RD. Commonality analysis: A method for decomposing explained variance in multiple regression analyses. Human Communication Research. 1979;5:355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Siegling AB, Saklofske DH, Vesely AK, Nordstokke DW. Relations of emotional intelligence with gender-linked personality: Implications for a refinement of EI constructs. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;52:776–781. [Google Scholar]

- Smits DJ, Boeck PD. From BIS/BAS to the big five. European Journal of Personality. 2006;20:255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB, Seyle C. Personality psychology’s comeback and its emerging symbiosis with social psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:155–165. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft R. The ability to judge people. Psychological Bulletin. 1955;52:1–23. doi: 10.1037/h0044999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A. Structures of mood and personality and their relevance to assessing anxiety, with an emphasis on self-report. In: Tuma AH, Maser JD, editors. Anxiety and the anxiety disorders. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1985. pp. 681–716. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon PE. Some characteristics of the good judge of personality. Journal of Social Psychology. 1933;4:42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Völter C, Strobach T, Aichert DS, Wöstmann N, Costa A, Möller HJ, Ettinger U. Schizotypy and behavioural adjustment and the role of neuroticism. PloS one. 2012;7:e30078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DG. Neuroticism and extraversion in different factors of the affect intensity measure. Personality and Individual Differences. 1989;10:1095–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. Affective forecasting: Knowing what to want. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. The impact bias is alive and well. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;105:740–748. doi: 10.1037/a0032662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TD, Wheatley TP, Meyers JM, Gilbert DT, Axsom D. Focalism: A Source of durability bias in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:821–836. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelenski JM, Larsen RJ. Susceptibility to affect: A comparison of three personality taxonomies. Journal of Personality. 2001;67:761–791. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelenski JM, Larsen RJ. Predicting the future: How affect-related personality traits influence likelihood judgments of future events. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:1000–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Zelenski JM, Whelan DC, Nealis LJ, Besner CM, Santoro MS, Wynn JE. Personality and affective forecasting: Trait introverts underpredict the hedonic benefits of acting extraverted. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104:1092–1108. doi: 10.1037/a0032281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zientek LR, Thompson B. Commonality analysis: Partitioning variance to facilitate better understanding of data. Journal of Early Intervention. 2006;28:299–307. [Google Scholar]