Abstract

Traumatic intracranial pseudoaneurysm is a rare complication of blunt trauma. It is even more rare when it presents as epistaxis. Massive epistaxis of a ruptured intracranial internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm is a major cause of mortality, which requires emergency intervention. We report a case of traumatic intracranial internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to skull base fracture, which presented with delayed onset of epistaxis. This was successfully treated by primary endovascular coil embolization. We discuss endovascular treatment options and review the literature.

Epistaxis is mostly a self-limiting medical condition.1 Traumatic intracranial pseudoaneurysm is a rare complication of blunt trauma. It is even more rare to present as epistaxis. Unfortunately, massive, even fatal epistaxis can occur secondary to the rupture of pseudoaneurysms of major intracranial vessels.2 The timely treatment of these lesions is necessary for the safety of these patients. There are several modalities of treatment of these lesions with varying degrees of complexity and inherent morbidity that needs to be tailored to the patients’ condition and access to specialized care. We report a case of traumatic intracranial internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to skull base fracture, which presented by delayed onset of epistaxis. This was successfully treated by primary endovascular coils embolization, as a stand-alone therapy given the peculiarity of the patient presentation and logistical aspects of his care. We discuss endovascular treatment options and literatures review.

Case Report

A 28-year-old man was transferred from another institution with uncontrolled intermittent epistaxis. He had a history of road traffic accident 9 months earlier with mild traumatic brain injury associated with multiple skull base fractures, from which he was stabilized and recovered completely. Two weeks prior to arrival, he developed torrential nasal bleeds that stopped spontaneously the first time, but required nasal packing the next time it occurred a few days later. The bleeds were becoming more frequent and heavier, thus he was transferred for urgent intervention. His evaluation included a CT of the brain that showed multiple areas of encephalomalacia (Figure 1). The sphenoid sinuses showed complete opacification with hyperdensity on both sides denoting hemosinus (Figure 2). Multiple non-displaced skull fractures were seen with a small bony defect at the superior aspect body the sphenoid bone on the left side (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Computer tomography of the brain showing multiple areas of encephalomalacia with no evidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

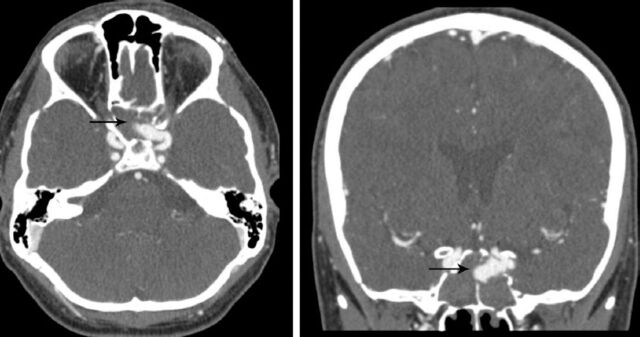

Figure 2.

The sphenoid sinuses show complete opacification with hyperdensity on both sides denoting hemosinus.

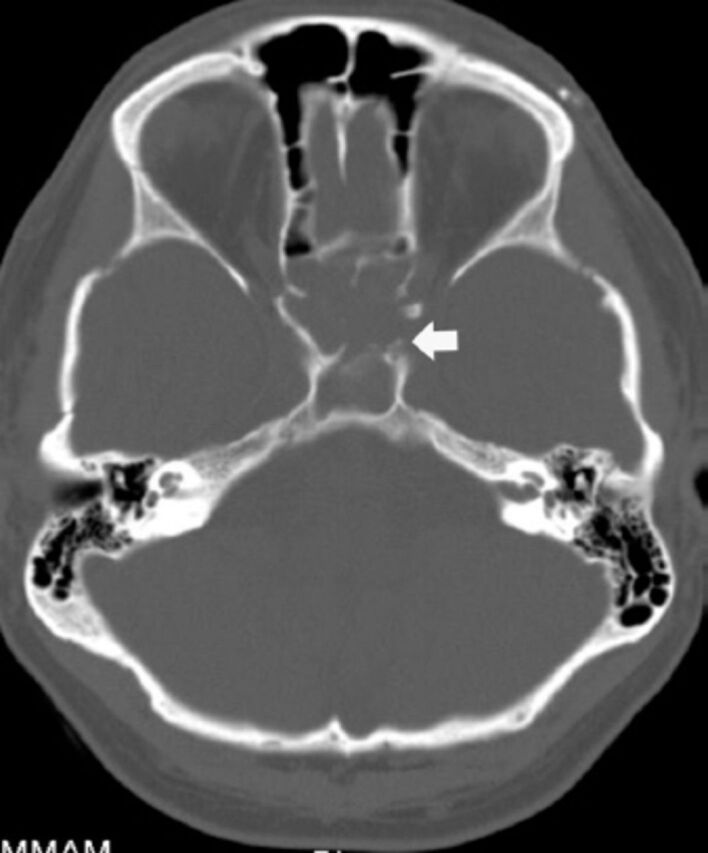

Figure 3.

Multiple non-displaced skull fractures are seen with a small bony defect at the superior aspect body of sphenoid bone on the left side.

The CT angiogram of the brain demonstrated the presence of a large arterial out-pouching arising from the cavernous part of the left internal carotid artery protruding through a defect at the left superior-lateral aspect of the sphenoid sinus representing pseudoaneurysm, with its tip projecting well into the right side of the sphenoid sinus measuring 16 x 8 mm (Figure 4). He was shifted to the angiographic suite for embolization. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation to protect the airway in case of rebleeding during the procedure.

Figure 4.

Computer tomography angiogram of the brain demonstrating the presence of a large arterial out-pouching arising from the cavernous part of the left internal carotid artery protruding through a defect at the left superior-lateral aspect of the sphenoid sinus representing pseudoaneurysm, with its tip projecting well into the right side of sphenoid sinus measuring 16 x 8 mm.

A left internal carotid artery cerebral angiogram was performed using the standard projections, as well as oblique projections, and showed an aneurysm arising from the paraophthalmic segment of the internal carotid artery that projects anteriorly and medially into the sphenoid sinus (Figure 5). The aneurysm was multilobulated with multiple daughter sacs. It had a small neck to dome ratio. We decided to proceed with primary coiling. The aneurysm was cannulated using Echelon 14 microcatheter (eV3, Irvine, MN, USA) over 0.014” Silverspeed microguidewire (eV3, Irvine, MN, USA). Multiple detachable bare metal coils were deployed into the aneurysm to pack it tightly in sequential “baskets” distal first then proximal using 9 mm diameter coils for each to obviate the need for an adjunctive device. A completion angiogram showed near complete obliteration of the pseudoaneurysm with small residual flow into the neck with preservation of the origin, and flow into the ophthalmic artery (Figure 6). He tolerated the procedure and was extubated upon completion. There was no immediate complications and he received the post coiling heparinization protocol for 24 hours as is the usual practice at our institution when the coil mass is close to the origin of an important vessel, in this case, the ophthalmic artery. He was discharged from the hospital few days later. He was then followed up clinically at the outpatient and seen in the outpatient clinic with no further episodes of nasal bleeding or new neurologic deficit. A one-year follow up showed a stable coil mass with no evidence of recanalization.

Figure 5.

Left internal carotid artery oblique cerebral angiogram showing an aneurysm arising from the paraophthalmic segment of the internal carotid artery that projects anteriorly and medially into the sphenoid sinus.

Figure 6.

Completion angiogram showing near complete obliteration of the pseudoaneurysm with small residual flow into the neck with preservation of the origin and flow into the ophthalmic artery.

Discussion

Epistaxis is a common medical condition mainly arising from the anterior nasal cavity and self limited with compression. The causes of epistaxis include but not limited to dryness of the nasal mucosa, digital trauma, coagulopathy, hypertension, and blood dyscrasias. These are, for the most part, managed conservatively or with nasal packing.1 In cases where epistaxis is difficult to control or in the presence of risk factors, such as head trauma, radiation therapy, or head and neck tumors, a pseudoaneurysms should be considered as the cause of epistaxis.

A trauma patient can have epistaxis during presentation to the emergency department from injury of either the internal or external carotid artery branches. Injury to the external carotid artery branches is the most injury common cause of epistaxis, especially, the internal maxillary artery.2 Sometimes the injury will affect the skull base segments of the internal carotid artery due to the fracture edge injuring the artery during the deceleration of the head, as in our case with multiple skull base fractures.3 It can present as epistaxis immediately at the time of injury or in a delayed manner. If CT failed to show the site of injury leading to epistaxis, conventional angiography is indicated, which is the gold standard in evaluating these patients.4 If both CT angiography and digital subtraction angiography fails to show the site of injury and the patient continues to have epistaxis, repeat imaging in 3 weeks is advised; as 90% of patients with pseudoaneurysm will present in 3 weeks after injury, some of which have been reported to be fatal.5 Prompt treatment of pseudoaneurysms is warranted due to the high morbidity and mortality if not recognized and treated. The mortality rate if ruptured is up to 50%.6 An open surgical approach is geared towards exclusion of the aneurysm with parent vessel preservation of the artery or occlusion if necessary to allow for flow-reversal to heal the aneurysmal segment. Exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm is the definite treatment with the best long-term outcome, however, this is not always an option. The patient must have good collateral supply and pass the balloon occlusion test if feasible. Having good collaterals and passing the balloon occlusion test is not a guarantee for the patient to have no complications after parent vessel occlusion. It is important in this context to keep in mind that 22% of patients who passed the BTO developed complication after sacrificing the artery.7

With the advances in endovascular techniques and equipment, these have replaced the previous use of the open surgical technique for both parent vessel occlusion and preservation of the artery. The same requirements and risks apply for parent vessel occlusion by the endovascular method as the open surgical technique with the risk of strokes. The choice of endovascular technique is variable and is individualized on a case by case basis according to the anatomy and clinical status of the patient. Packing of the pseudoaneurysm with coils is achievable, but it has risks of rupture in the acute phase when it is contained by the hematoma only.8 This option is sufficient in most cases where the neck of the pseudoaneurysm is narrow as in our case. If the neck is wide, coiling can be performed with balloon remodeling. The advantage of these 2 techniques is sparing the patient the need for antiplatelets therapy post procedure in case a stent is deployed.

If the vessel wall is dysplastic and the neck is wide, treatment can be performed with the stent assistance prior or after placement of the coils to reconstruct the vessel and contain the coil mass. This can be performed with the use of single stent or with a stent within stent technique.9 If the operator feels the pseudoaneurysm is small or too fragile to hold the coils, treatment can be performed with stents only. Pseudoaneurysms were reported to heal after placement of 2-3 overlapping intracranial stents to divert the flow away from the aneurysm, and to help reconstruct the wall of the artery by neointima formation on the stents struts.9 Recently, several articles were published on the use of flow diverting stents and covered stents as the sole treatment, or with coils as the treatment for the pseudoaneurysms.10 Covered stents show limited success compared with flow diverting stents due to the stiffness of the delivery system, which needs to be pushed through a diseased and tortuous anatomy risking complications of another dissection or vasospasm. The other risk of covered stents is the occlusion of adjacent branches, such as the posterior communicating or the ophthalmic arteries.11

In conclusion, patients who presents with massive epistaxis following a history of head trauma, no matter how recent or remote, should be evaluated for the presence of pseudoaneurysm as the cause, especially of the internal carotid artery. Treatment should be prompt due to the high mortality if not recognized. Endovascular techniques are the treatment method of choice, which should be individualized to the patient’s condition, risk factors, and anticipated compliance with medical treatment and follow up plans.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Pope LE, Hobbs CG. Epistaxis:an update on current management. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:309–314. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.025007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang CW, Xie XD, You C, Mao BY, Wang CH, He M, et al. Endovascular treatment of traumatic pseudoaneurysm presenting as intractable epistaxis. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11:603–611. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2010.11.6.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheong JH, Kim JM, Kim CH. Bony protuberances on the anterior and posterior clinoid processes lead to traumatic internal carotid artery aneurysm following craniofacial injury. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;49:49–52. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2011.49.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stafa A, Leonardi M. Role of neuroradiology in evaluating cerebral aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol. 2008;14(Suppl 1):23–37. doi: 10.1177/15910199080140S106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontela PS, Tampieri D, Atkinson JD, Daniel SJ, Teitelbaum J, Shemie SD. Posttraumatic pseudoaneurysm of the intracavernous internal carotid artery presenting with massive epistaxis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7:260–262. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000216418.01278.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purgina B, Milroy CM. Fatal traumatic aneurysm of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery with delayed rupture. Forensic Sci Int. 2015;247:e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elias AE, Chaudhary N, Pandey AS, Gemmete JJ. Intracranial endovascular balloon test occlusion:indications, methods, and predictive value. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2013;23:695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jao SY, Weng HH, Wong HF, Wang WH, Tsai YH. Successful endovascular treatment of intractable epistaxis due to ruptured internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to invasive fungal sinusitis. Head Neck. 2011;33:437–440. doi: 10.1002/hed.21305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Juretschke F, Castro E, Mateo Sierra O, Iza B, Manuel Garbizu J, Fortea F, et al. Massive epistaxis resulting from an intracavernous internal carotid artery traumatic pseudoaneurysm:complete resolution with overlapping uncovered stents. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009;151:1681–1684. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amenta PS, Starke RM, Jabbour PM, Tjoumakaris SI, Gonzalez LF, Rosenwasser RH, et al. Successful treatment of a traumatic carotid pseudoaneurysm with the Pipeline stent:Case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2012;3:160. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.105099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan HQ, Li MH, Zhang PL, Li YD, Wang JB, Zhu YQ, et al. Reconstructive endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with the Willis covered stent:medium-term clinical and angiographic follow-up. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:1014–1020. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.JNS10373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]