ABSTRACT

Topoisomerase IIα is an essential enzyme that resolves topological constraints in genomic DNA. It functions in disentangling intertwined chromosomes during anaphase leading to chromosome segregation thus preserving genomic stability. Here we describe a previously unrecognized mechanism regulating topoisomerase IIα activity that is dependent on the F-box protein Fbxo28. We find that Fbxo28, an evolutionarily conserved protein, is required for proper mitotic progression. Interfering with Fbxo28 function leads to a delay in metaphase-to-anaphase progression resulting in mitotic defects as lagging chromosomes, multipolar spindles and multinucleation. Furthermore, we find that Fbxo28 interacts and colocalizes with topoisomerase IIα throughout the cell cycle. Depletion of Fbxo28 results in an increase in topoisomerase IIα−dependent DNA decatenation activity. Interestingly, blocking the interaction between Fbxo28 and topoisomerase IIα also results in multinucleated cells. Our findings suggest that Fbxo28 regulates topoisomerase IIα decatenation activity and plays an important role in maintaining genomic stability.

KEYWORDS: Cell cycle, decatenation, F-box protein, Fbxo28, mitosis, SCF, Topoisomerase IIα

Introduction

Topoisomerases are ubiquitous, essential nuclear enzymes involved in many aspects of DNA metabolism, including transcription, replication, recombination, and chromosome segregation during mitosis. Type IIα topoisomerases (Topo IIα) bind to both strands of double-stranded DNA by introducing double strand breaks thus triggering separation of daughter strands during DNA replication. Although supercoiled DNA can be relaxed by both type I and type II topoisomerases only Topo IIα can catenate or decatenate closed circular DNA (reviewed in 1). Topo IIα is cell cycle-regulated with protein levels increasing in G2/M phase and declining at the end of M-phase.2 Defects in type II topoisomerase–mediated processes can cause a delay in or arrest of cell cycle progression in response to unresolved topological intertwining between daughter duplexes. Inactivation of Topo IIα at late anaphase induces polyploidy as cells continue replicating DNA without cell division.3,4 Therefore, type II topoisomerase enzymes which are conserved from bacteria to human cells are also crucial for the segregation of chromosomes.5,6,7 A decatenation checkpoint monitors the decatenation status of chromosomes and delays entry into mitosis until the chromosomes are fully disentangled.8,9 Topo IIα is ubiquitylated in a BRCA1-dependent manner which correlates with higher DNA decatenation activity.10 Topo IIα is also a phosphorylation target of Plk1 in both interphase and mitosis.11 In addition, it has been shown that CK2 can modulate Topo IIα activity.12 Furthermore, the DNA relaxation activity of IIα is stimulated through phosphorylation by CK2.12

Ubiquitylation, the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to a protein substrate, is involved in a number of cellular processes.13 In a sequence of enzymatic events ubiquitin is activated by E1 (ubiquitin-activating) enzyme and transferred to an E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating) enzyme. Substrate specificity is mediated by E3 ubiquitin ligases that transfer ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to the specific substrate. The largest family of E3s are the cullin-RING based-ubiquitin ligases (CRLs). In mammalian cells, there are 8 cullin protein family members, CUL1-3, CUL4A and CUL4B, CUL5, CUL7 and CUL9.14 Depending on their combination, CRLs can modulate and ubiquitylate distinct substrates.15 The SCF(Skp1-Cul1-F-box) complex is the so far best characterized subfamily and consists of 4 subunits, Cul1, Rbx1, Skp1 and the substrate-binding F-box protein. F-box proteins are defined by a 40–50 amino acid F-box domain that binds Skp1.16,17 The Fbxw subfamily of F-box proteins recruits substrates through the WD40 domain, Fbxl proteins through leucine-rich repeats and the Fbxo subfamily with yet unknown domain(s). One well characterized F-box protein is Fbxw7, a tumor suppressor protein that regulates the levels of a number of substrates, i.e. cyclin E, c-MYC and c-Jun by ubiquitin-mediated degradation.18 A mechanism how Fbxw7 itself is regulated occurs through Plk2-dependent phosphorylation leading to a reduction of Fbxw7 protein levels.19 In the past years, also non-canonical, SCF-independent roles of human F-box proteins have been described.20

The SCF-Fbxo28 protein complex was recently identified as an E3 ubiquitin ligase that is involved in the regulation of c-MYC driven transcription, transformation and tumorigenesis. Cdk1-dependent phosphorylation of Fbxo28 is required for efficient ubiquitylation but not degradation of c-MYC by stimulating c-MYC-p300 interactions at target promoters.21 Apart from c-MYC, specific substrates of Fbxo28 remain to be identified.

Here we show that the F-box protein Fbxo28 regulates Topo IIα decatenation activity. We find that Fbxo28 interacts with Topo IIα both in vitro and in vivo. Ablation of Fbxo28 function leads to prolonged mitosis and mitotic defects as multinucleation, a phenotype that was also observed when the interaction of Fbxo28 and Topo IIα was impaired. We conclude that Fbxo28 regulates Topo IIα decatenation activity thus ensuring proper mitotic progression.

Results

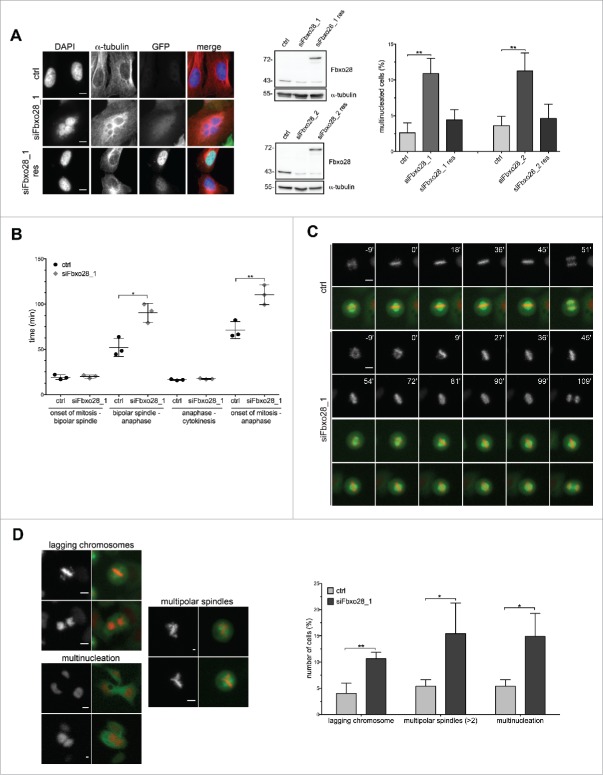

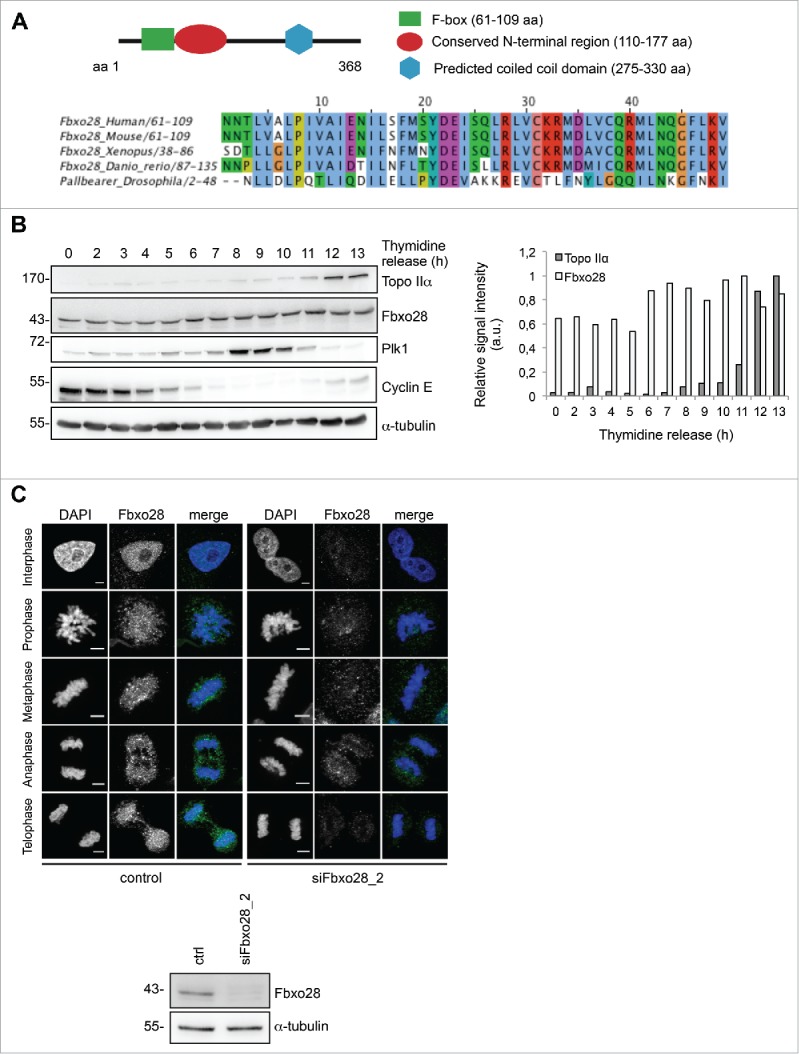

Depletion of Fbxo28 leads to multinucleation and prolonged mitosis

To unravel the function of the human F-box protein Fbxo28 in more detail, we first analyzed its evolutionary conservation and found that homologues exist both in vertebrates and Drosophila22,23 (Fig. 1A). To investigate whether Fbxo28 protein levels are regulated during the cell cycle, HeLa cells were synchronized with a double thymidine block at the G1/S boundary and released for different time points. Cell cycle progression was controlled by Western blot analysis of cell cycle marker proteins. We found that Fbxo28 protein levels increase and peak at the G2/M transition (Fig. 1B). To further study the localization of Fbxo28 during the cell cycle and for confirmation of the results with a second antibody, we decided to generate peptide antibodies in rabbits against Fbxo28. The specificity of this antibody has been verified by siRNA depletion of Fbxo28 (Fig. S1A). As shown in Fig. 1C endogenous Fbxo28 localized in the nucleus during interphase and in the vicinity of mitotic chromosomes during mitosis. We then generated a doxycycline-inducible GFP-Fbxo28 HeLa cell line and verified the localization of the chimeric GFP-Fbxo28 upon induction (Fig. S1B). As Fbxo28 protein localization is regulated during the cell cycle, we aimed to study the possible function of the protein in mitosis. We depleted Fbxo28 utilizing different siRNAs targeting different regions of Fbxo28 mRNA (Fig. S1A). Interestingly, we observed that siRNA-mediated downregulation of Fbxo28 leads to cells that harbor several nuclei (Fig. 2A). Around 12% of U2OS cells exhibited multinucleation in response to depletion of Fbxo28. To exclude off-target effects caused by siRNA-treatment we performed rescue experiments by generating the corresponding siRNA (siFbxo28 1,2 res)-resistant version of GFP-Fbxo28 which was coexpressed during siRNA-mediated depletion of endogenous Fbxo28. siRNA-resistant GFP-Fbxo28 was able to reduce the multinucleation phenotype nearly back to control levels, which was not the case upon expression of the GFP control (Fig. 2A). To explore the effect of Fbxo28 ablation on mitotic progression and duration in more detail and in real time, we used time-lapse video microscopy. Therefore, Fbxo28 was depleted in HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-α−tubulin/ RFP-H2B and cells were monitored 72h post siRNA transfection. Cells transfected with control siRNA completed mitosis within an average of around 71 min. Upon downregulation of Fbxo28 mitosis was prolonged up to 109 min (Fig. 2B). This was caused by an extended duration from bipolar spindle formation until anaphase (Fig. 2B and C, Movies 1 and 2). The average timing for bipolar spindle formation (19 min mean duration time from nuclear envelope breakdown until bipolar spindle formation) and the separation of chromosomes (mean duration time of 17 min starting from anaphase to cytokinesis) was not altered. This indicates that the overall prolonged time of mitosis could be due to problems in chromosome congression. In addition to a prolonged mitosis, mitotic defects were observed upon Fbxo28 siRNA-treatment manifesting in lagging chromosomes, multipolar spindles and multinucleated cells (Fig. 2D). We frequently observed multipolar spindle formation (Movies 3 and 4). These multipolar spindles often led to multinucleated cells which might point to a failure in chromosome attachment, in decatenation or in cytokinesis.

Figure 1.

Fbxo28 is an evolutionary conserved nuclear protein. (A) Scheme of Fbxo28 structure and protein alignment of the Fbxo28 F-box sequence from Human, Mouse, Xenopus, Danio rerio and Drosophila reveals a high conservation in multiple species. (B) HeLa cells were synchronized by a double thymidine block and released for 13 h. Fbxo28 (Fbxo28 ab2) and Topo IIα (Topo IIα ab2) protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. Cyclin E and Plk1 were used to monitor cell cycle progression. α−tubulin served as a loading control. The quantification shows relative Topo IIα and Fbxo28 signal intensities after normalization to the α−tubulin signals. (C) For indirect immunofluorescence analysis HeLa cells were treated twice with 10 nM control or Fbxo28 siRNA for 48 h. Cells were fixed and stained with Fbxo28 ab1 (green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue) and endogenous Fbxo28 localization was imaged throughout the cell cycle. Scale bar, 5 µm. Western blot showing downregulation of Fbxo28 (Fbxo28 ab1). α-tubulin served as a loading control.

Figure 2.

Fbxo28 depletion leads to multinucleation and prolonged mitosis. (A) U2OS cells were transiently transfected with control (ctrl) or Fbxo28 siRNA (siFbxo28_1, siFbxo28_2) and with GFP alone or siRNA-resistant version of GFP-Fbxo28 (res). Cells were synchronized with a double thymidine block for 48 h. Multinucleated cells (n = 450–700 cells for siFbxo28_2; n = 200 cells for siFbxo28_1) were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining from 3 independent experiments. Representative images of multinucleation upon Fbxo28 siRNA depletion. Western blot showing downregulation of Fbxo28 and expression of GFP-Fbxo28 siRNA-resistant plasmids (using Fbxo28 ab1). Quantification showing percentages of multinucleated cells. Error bars in the graph represent standard deviation (SD). Student's t-test was used to calculate p-values. ** denotes significance at P < 0.01. (B) HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-α-tubulin/RFP-H2B were transfected twice with control (ctrl, GL2) or Fbxo28 siRNA (siFbxo28_1) for 72 h and synchronized by a double thymidine block followed by live-cell imaging for 10–12 h. Quantification of live-cell imaging displaying the time from either onset of mitosis to the formation of a bipolar spindle, bipolar spindle to anaphase or anaphase to cytokinesis or onset of mitosis until anaphase. Scatter dot plot showing mean of 3 unbiased experiments. n = 38–127 cells each from 3 independent experiments. (C) Representative frame series of movies from prometaphase to anaphase of control and Fbxo28 siRNA treated cells with continuous time points (min) (gray: RFP-H2B; merge: GFP-α-tubulin/RFP-H2B). (D) HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-α-tubulin/RFP-H2B were treated as described in (B). Representative images of cells with lagging chromosomes, multinucleation and multipolar spindles upon Fbxo28 downregulation are shown (left). Quantification of live-cell imaging of lagging chromosomes, multinucleation and multipolar spindles (right). n = 50–145 cells each from 3 independent experiments. Scale bar, 10 µm. Error bars in the graph represent standard deviation, SD. Student's t-test was used to calculate p-values. *denotes significance at p < 0.05; **denotes significance at p < 0.01.

A control mechanism that arrests cells with spindle defects or defective kinetochore-microtubule attachments at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition is the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC).24 To show that the delay in mitosis in Fbxo28-depleted cells is not due to activation of the SAC, Western blotting was performed using an antibody against a marker of an active SAC, BubR1. We did not detect an increased phosphorylation of BubR1 in Western blot suggesting that the SAC is not activated upon ablation of Fbxo28 (Fig. S2). Together, these results imply that Fbxo28 exerts a critical function during mitosis by interfering with mitotic progression at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition.

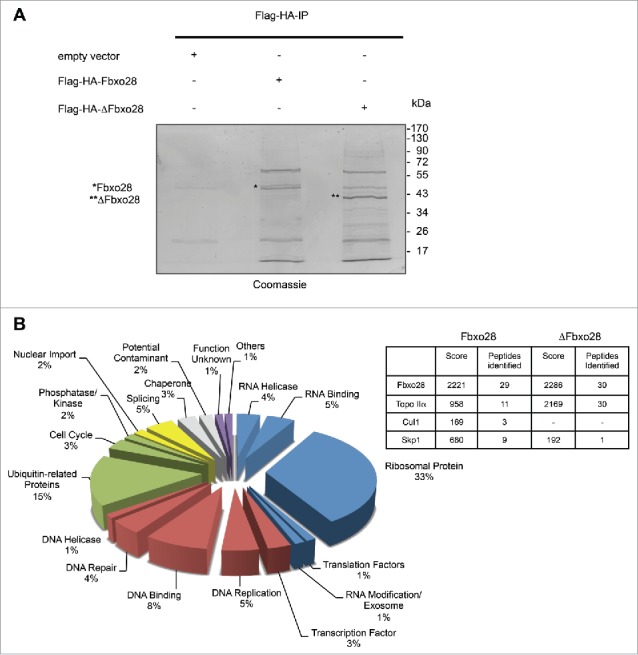

Fbxo28 interacts with topoisomerase IIα

Having established that Fbxo28 depletion delays mitotic progression, we aimed to identify novel interaction partners of the SCF-Fbxo28 ubiquitin ligase to obtain a better insight into its mitotic function. Flag-HA-Fbxo28 or Flag-HA-ΔFbox-Fbxo28 (ΔFbxo28) were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells subjected to a sequential immunopurification approach comprising immobilization on anti-Flag resin and elution with the 3x-Flag-peptide in the first step, with subsequent immobilization on anti-HA resin and elution with HA-peptide in the second step. The mutant protein, ΔFbxo28, that cannot form SCF complexes, was used to exclude that the observed interaction is mediated by Skp1 or Cul1. Eluted binding partners were analyzed by mass spectrometry (Fig. 3A). Most of the identified Fbxo28 binding partners were ubiquitin-related proteins, ribosomal proteins and DNA-binding proteins. Interestingly, among the putative interaction partners that we identified for Fbxo28, we found Topo IIα (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Identification of Fbxo28 interacting proteins. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-HA-Fbxo28, Flag-HA-ΔFbxo28 or control plasmid (Flag). MG132 was added 4h before harvesting the cells. Fbxo28 was immunoprecipitated first with an anti-Flag tag antibody followed by Flag-peptide elution. The eluate was then subjected to a second anti-HA immunoprecipitation with subsequent HA-peptide elution. The final elutions were separated by SDS-PAGE and proteins were stained with colloidal coomassie. The gel was sent for mass spectrometry analysis. Asterisk (*) indicates eluted Flag-HA-Fbxo28, double asterisk (**) indicates Flag-HA-ΔFbxo28. (B) Classification of identified proteins by functional category. Numbers indicate the percentage of identified proteins in each category. The table summarizes a selection of specifically identified proteins in the Flag-HA-Fbxo28 IP, Cul1 and Skp1 as known interaction partners and Topo IIα as a novel Fbxo28 interaction partner.

To investigate whether Fbxo28 and Topo IIα protein levels are similarly regulated during the cell cycle, we made again use of the HeLa time course shown in Fig. 1B. We find that Topo IIα protein levels slightly start to increase around 8h after release from the thymidine block at about the same time when Plk1 protein levels start to increase which marks end of G2/beginning of M-phase. Topo IIα levels peak during G1 phase after Plk1 levels decrease again (Fig. 1B).

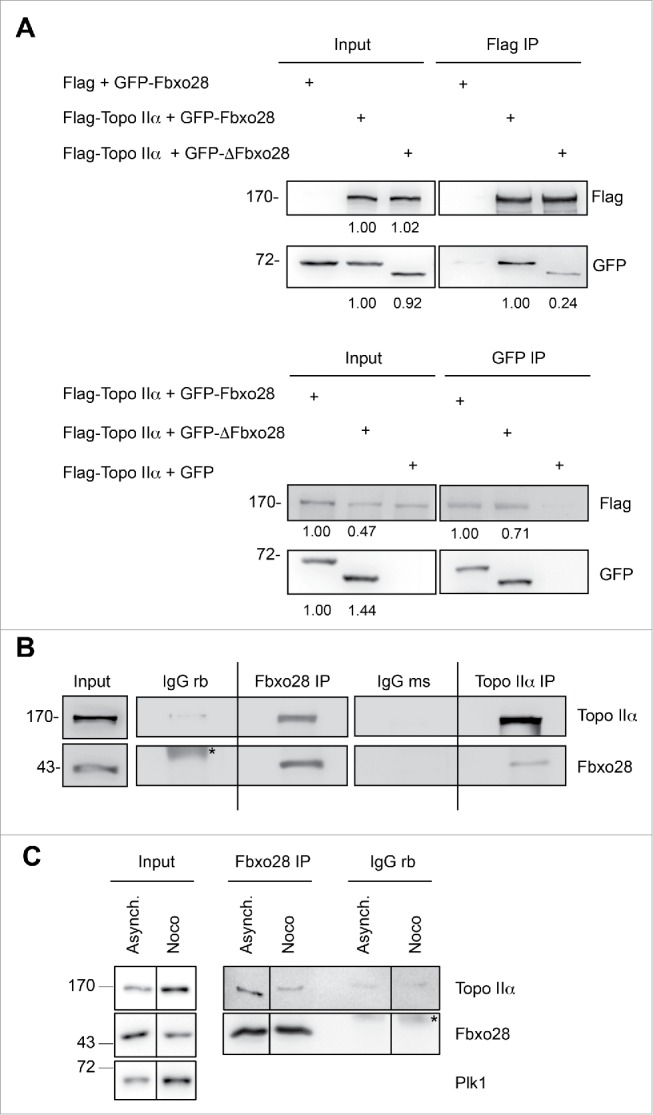

We then aimed to confirm the interaction between Fbxo28 and Topo IIα, a protein essential for faithful mitotic chromosome segregation. We first reproduced this interaction by using Flag-Topo IIα and GFP-Fbxo28 overexpression in HEK293T cells followed by reciprocal immunoprecipitations (Fig. 4A). The interaction between Fbxo28 and Topo IIα was partially dependent on the F-box as a weaker binding could be observed in both directions upon expression of GFP-ΔFbxo28 and Flag-Topo IIα. To further verify this interaction also in vivo, we immunoprecipitated endogenous Fbxo28 and showed that endogenous Topo IIα was found in the immunoprecipitates. Vice versa, endogenous Fbxo28 protein was detected in immunoprecipitates with Topo IIα antibodies (Fig. 4B). We also observed interaction of Topo IIα and Fbxo28 in mitotic cell extracts although to a smaller extent as in asynchronous cells (Fig. 4C). The interaction between the 2 proteins could also be confirmed in vitro in GST-pulldown experiments using recombinant GST-tagged Fbxo28 and IVT [35S]-Topo IIα (Fig. S3A). Furthermore, we found a clear colocalization of endogenous Fbxo28 and Topo IIα proteins in the nucleus throughout the cell cycle (Fig. S3B). Taken together, our data show that Fbxo28 and Topo IIα are colocalizing in the vicinity of DNA and are interacting in vivo and in vitro.

Figure 4.

Interaction between Topo IIα and Fbxo28. (A) Co-immunoprecipitation of Flag-Topo IIα and GFP-Fbxo28 or GFP-ΔFbxo28. Lysates from HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and subjected to immunoprecipitations using anti-Flag or anti-GFP antibodies. Immunoprecipitations were washed 5 times in lysis buffer. Input and IP samples were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against Flag-tag or GFP-tag. Quantifications of the Flag and GFP signal intensities are indicated below the corresponding blots. Flag and GFP signal intensities in the IP samples were normalized using the bait signal intensities. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous Fbxo28 and Topo IIα. Endogenous Fbxo28 and Topo IIα were immunoprecipitated from HEK293T lysates by anti-Fbxo28 (Fbxo28 ab2) and anti-Topo IIα (Topo IIα ab2) antibodies. IP with non-specific IgGs served as a control. Co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Asterisk (*) indicates unspecific band. The dividing lane marks the grouping of images from different parts of the same gel, as an intervening lane was removed for presentation purposes. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous Fbxo28 and Topo IIα. Endogenous Fbxo28 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of asynchronous or Nocodazole (Noco)-treated (mitotic) cells by anti-Fbxo28 antibodies (Fbxo28 ab2). IP with non-specific rabbit IgGs served as a control. Co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blotting using Topo IIα ab2 and Fbxo28 ab2. Plk1 was detected to monitor the cell cycle stage. Asterisk (*) indicates IgG heavy chains. The dividing lanes mark the grouping of images from different parts of the same gel, as an intervening lane was removed for presentation purposes.

Interaction between Fbxo28 and Topo IIα is required for proper progression through mitosis

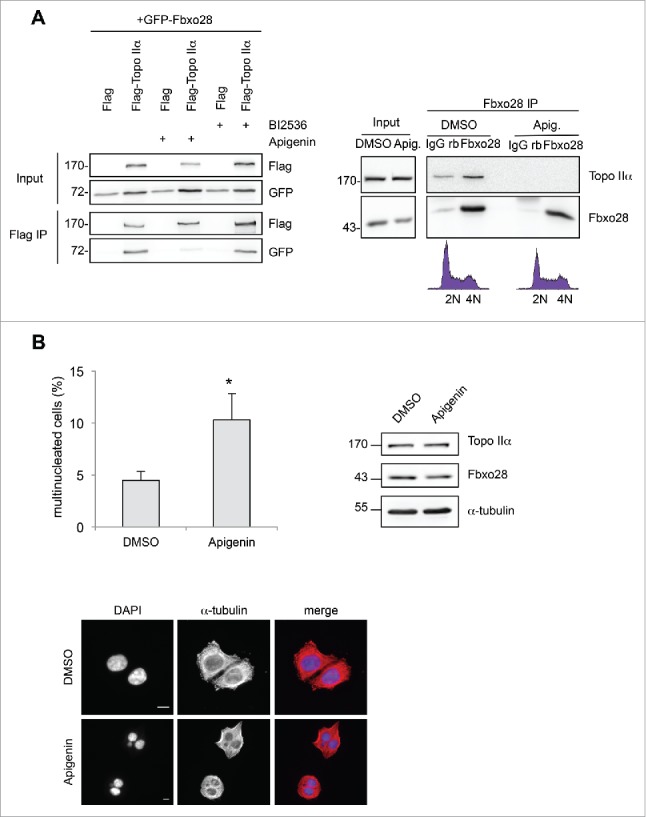

Posttranslational modifications including phosphorylation of Topo IIα have been shown to regulate its function. Both Plk1 and CK2 kinases have been found to regulate Topo IIα activity.11,12 As it is conceivable that the interaction between Topo IIα and Fbxo28 is dependent on phosphorylation by CK2 or Plk1 kinases we made use of small molecule inhibitors that block their enzymatic activity. Intriguingly, we found that treatment of cells with the Plk1 inhibitor BI2536 did not have an effect on the binding whereas the CK2 inhibitor Apigenin efficiently blocked the binding between Fbxo28 and Topo IIα after overexpression of both proteins. Also the interaction of endogenous Fbxo28 and Topo IIα was blocked after treatment with the CK2 inhibitor (Fig. 5A). We in turn asked whether Fbxo28 would regulate Topo IIα activity in mitosis. To analyze the function of the Fbxo28-Topo IIα interaction in mitosis we again used Apigenin treatment to block their interaction. We observed a multinucleation phenotype when binding between Fbxo28 and TopoIIα was impaired (Fig. 5B). Intriguingly, also down-regulation of Fbxo28 leads to a similar multinucleation phenotype (Fig. 2A). These results therefore indicate that the defects observed in mitosis are induced by loss of the Fbxo28 and TopoIIα interaction. Interestingly, Fbxo28 is also an in vitro substrate of CK2 indicating that this phosphorylation might also account or contribute to the multinucleation phenotype (Fig. S4).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of Fbxo28 binding to Topo IIα leads to multinucleated cells. (A) left, HEK293T cells were either transfected with GFP-Fbxo28 and Flag alone (control) or with Flag-Topo IIα for 24 h and treated either with 100 nM BI2536 (Plk1 inhibitor) for 2 h or 50 µM Apigenin (CK2 inhibitor) for 5 h. Flag-Topo IIα was immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag antibodies and samples were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against the Flag or GFP-tag. Right, Endogenous Fbxo28 (Fbxo28 ab2) and Topo IIα (Topo IIα ab2) were immunoprecipitated from HEK293T lysates (treated with either DMSO or 50 µM Apigenin for 5h). IP with non-specific IgGs served as a control. Co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blotting. (B) To synchronize cells in mitosis HeLa cells were treated with thymidine for 22 h, released from the thymidine block for 6 h and arrested in mitosis by Nocodazole treatment for 4 h. After mitotic shake-off and release from the Nocodazole block, 50 µM Apigenin was added to the cells for 5 h in order to inhibit CK2 kinase activity. Control cells were treated with DMSO. Multinucleation was analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy in 3 independent experiments (n = 55–85 cells for each independent experiment). Representative images illustrate multinucleation upon Apigenin treatment. Scale bar: 10 µm. The graph shows a quantification of multinucleated cells. Error bars in the graph represent SD. Student's t-test was used to calculate p-values. *denotes significance at P < 0.05. Topo IIα (Topo IIα ab1) and Fbxo28 (Fbxo28 ab2) protein levels were monitored by Western blotting.

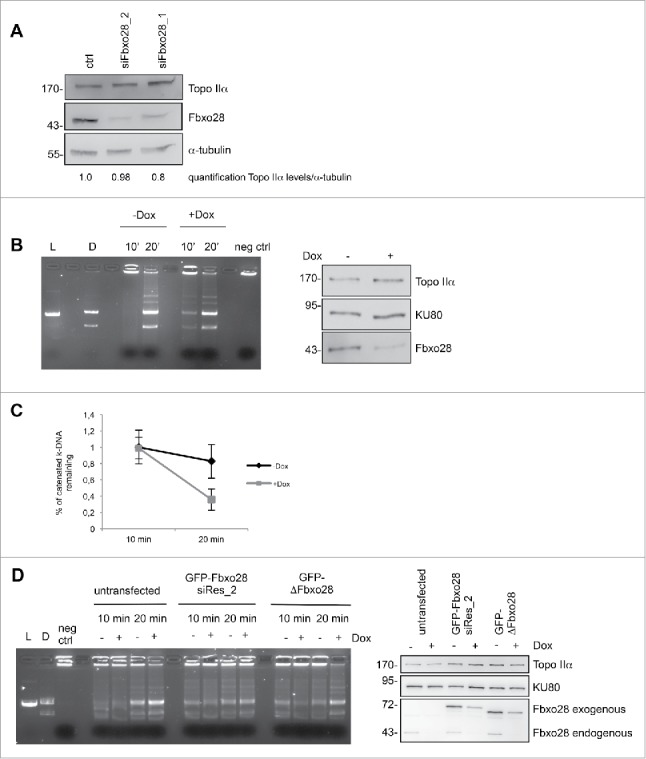

Fbxo28 regulates topoisomerase IIα induced DNA decatenation

Topo IIα is crucial for separating catenated chromosomes after DNA replication resulting in efficient chromosome condensation. As we found colocalization of Fbxo28 with Topo IIα in addition to their interaction in vitro and in vivo, we next investigated whether Fbxo28 might regulate Topo IIα protein levels. Therefore, Fbxo28 was downregulated with 2 different siRNAs and Topo IIα protein levels were monitored. We found that ablation of Fbxo28 function does not lead to a change in Topo IIα levels (Fig. 6A). As it has been previously shown that Topo IIα ubiquitylation by BRCA1 stimulates Topo IIα decatenation but not its degradation10 we investigated whether Fbxo28 might ubiquitylate Topo IIα. However, we did not observe an alteration in the ubiquitylation pattern of TopoIIα after Fbxo28 loss (Fig. S5), indicating that Fbxo28 is not ubiquitylating Topo IIα. To find out whether Fbxo28 is regulating Topo IIα dependent DNA decatenation activity, we performed in vitro decatenation assays using nuclear extracts from HeLa cells expressing doxycycline-inducible Fbxo28 shRNA that we generated using a Human Topoisomerase II assay kit. Briefly, 2 µg of nuclear extract was incubated with kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) for 10 or 20 min. After stopping the reactions, catenated versus decatenated DNA were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Fig. 6B shows an increase in decatenated DNA after 10 min upon Fbxo28 ablation (+Dox) compared to control cells (-Dox). This highter Topo IIα decatenation activity was not due to increase in Topo IIα protein levels as shown in the Western Blot. Quantification of the remaining k-DNA (kinetoplast DNA) showed also a 2-fold decrease in the absence of Fbxo28 (Fig. 6C). To confirm that the observed effect was specific, we performed a rescue experiment by co-expressing the corresponding siRNA (siFbxo28 1,2 res)-resistant version of GFP-Fbxo28 during siRNA-mediated depletion of endogenous Fbxo28. Expression of the mutant ΔFbxo28 could not rescue the increased decatenation activity (Fig. 6D). Together, these experiments show that Fbxo28 negatively regulates the decatenation activity of Topo IIα.

Figure 6.

Downregulation of Fbxo28 leads to an increased Topoisomerase IIα decatenation activity. (A) Fbxo28 downregulation does not affect Topo IIα levels. HeLa cells were transfected twice with 10 nM of control (GL2) or Fbxo28 oligos and incubated for 48 h. Cells were lysed and total protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting using Topo IIα ab1 and Fbxo28 ab2. Topo IIα protein levels were quantified relative to α-tubulin levels. (B) In vitro decatenation assay was carried out with nuclear extracts (2 µg) from Dox-inducible HeLa S/A shFbxo28 cell line (induced for 72 h). The reactions were stopped after 10 or 20 min and catenated vs. decatenated DNA was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. L, linearized k-DNA marker. D, decatenated k-DNA marker. Equally loaded amounts of Topo IIα (Topo IIα ab 2) and Fbxo28 (Fbxo28 ab 2) downregulation were verified by Western blotting (left). The DNA-binding protein KU80 served as a loading control. (C) Quantification of remaining k-DNA from 3 independent decatenation assays. (D) In vitro decatenation assay was carried out as in (b). Additionally GFP-Fbxo28 siRes_2 or GFP-ΔFbxo28 plasmids were transfected. Western blot showing equally loaded amounts of Topo IIα and Fbxo28 downregulation. L, linearized k-DNA marker. D, decatenated k-DNA marker.

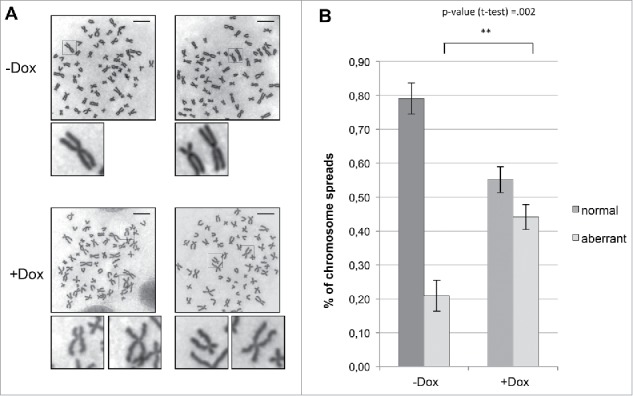

Centromeric enrichment of Topo IIα at distal arms of chromatids leads to unevenly condensed chromosomes with increasing rate of condensation toward the distal end (“curly“ phenotype).25 In order to confirm that silencing of Fbxo28 induces a similar phenotype caused by increased DNA decatenation, we prepared chromosome spreads in the presence and absence of Fbxo28. While control-treated cells showed a normal chromosomal conformation, silencing of Fbxo28 induced aberrant chromosome morphology characterized by a “curly“ phenotype which reflects a deficiency in chromatin structure (Fig. 7A). A number of these cells contained chromosomes that were unevenly condensed at centromeres with their distal arms showing a higher grade of condensation. The aberrant phenotype was increased about 2-fold when Fbxo28 function was impaired (Fig. 7B) and is likely caused by abnormal DNA decatenation.

Figure 7.

Fbxo28 depletion leads to aberrant chromosome morphology. HeLa S/A shFbxo28 cells induced with doxycycline for 72 h were treated with Colchicine for 1 h, harvested, and Giemsa-stained chromosome spreads were prepared. (A) Representative images show normal chromosome spreads in control (-Dox) cells and aberrant chromosome spreads in Fbxo28-depleted cells (+Dox), Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Quantification of the percentage of normal and aberrant chromosome spreads in control or Fbxo28-depleted cells from 3 independent experiments (n = 100 cells per experiment). Error bars in the graph represent SD. Student's t-test was used to calculate p-values. **denotes significance at P < 0.01.

Together, our findings indicate that Fbxo28 regulates Topo IIα decatenation activity.

Discussion

Fbxo28 is an evolutionary conserved F-box protein that has previously been shown to regulate c-MYC-dependent transcription.21 The present study provides evidence for a novel role of Fbxo28 in the regulation of Topo IIα. We found that Fbxo28 interacts both in vitro and in vivo with Topo IIα. We also observed that depletion of Fbxo28 leads to a delay in mitotic progression and results in multinucleation. In addition, as both proteins are localized in the nucleus it is conceivable that Fbxo28 regulates Topo IIα activity. Using Topo IIα-dependent decatenation assays we indeed found that ablation of Fbxo28 function led to an increase in Topo IIα decatenation activity (Fig. 6) suggesting that Fbxo28 might modulate Topo IIα activity. One possibility for Fbxo28 to regulate Topo IIα activity is to regulate its protein levels by ubiquitin-mediated degradation. However, as shown in Fig. 6A depletion of Fbxo28 did not alter Topo IIα protein levels. In addition, in spite of our intensive efforts we did not find a change in the ubiquitylation pattern of Topo IIα in the absence of Fbxo28 (Fig. S5). Nevertheless, we cannot entirely exclude that a weak ubiquitylation signal that is not detectable under the experimental conditions used regulates Topo IIα decatenation activity. As Topo IIα was shown to be ubiquitylated by other ubiquitin ligases, including BRCA1,10 it is possible that a potential Fbxo28-induced monoubiquitylation is covered by the polyubiquitylation signal caused by other ligases as BRCA1. It is also conceivable that Fbxo28 exerts its function to regulate Topo IIα independently of its ubiquitin ligase activity. In fact, ubiquitin-independent functions of F-box proteins and other ubiquitin ligases have been described previously.20,26 For example the HECT-type ubiquitin ligase NEDL1 enhances p53-mediated apoptotic death in a catalytic activity-independent manner.26 F–box proteins can selectively recognize different substrates/binding partners in a phosphorylation–dependent manner. We therefore postulate that Fbxo28 might regulate Topo IIα activity through direct binding which is dependent on phosphorylation by CK2 (Fig. 5A). This is supported by our finding that the binding between Fbxo28 and Topo IIα markedly decreased when CK2 catalytic activity was inhibited by the small molecule inhibitor Apigenin.27 Although Fbxo28 has been shown to form an active SCF-complex,21 our data suggest that Fbxo28 has an SCF-independent function in regulating Topo IIα decatenation. However, as a functional F-box seems to be required for the regulation of decatenation activity (Fig. 6D) and in part for interaction between Topo IIα and Fbxo28 (Fig. 4A), it is possible that Fbxo28 might only bind Skp1 to regulate Topo IIα activity. In fact, it has been shown previously that F-box protein/Skp1 dimers exist and are involved in centromere assembly and the recycling of endosomal components.28 Therefore, future work will be necessary to show whether dimerization of Fbxo28 and Skp1 regulates decatenation.

We also observed that silencing of Fbxo28 induces a slower mitotic progression between metaphase and anaphase and results in multipolar spindles and multinucleation (Fig. 2B–D). This phenotype could be caused by a failure in proper chromosome congression and centrosome fragmentation.29,30 Alternatively, the delay in mitosis might lead to both unscheduled sister chromatid separation and premature centriole disengagement followed by multipolar spindle formation (reviewed in31). Besides multinucleation in response to Fbxo28 downregulation, a similar phenotype has also been observed when the interaction between Fbxo28 and Topo IIα was inhibited upon CK2 inhibition.

In conclusion, our data indicate that Fbxo28 controls DNA decatenation through binding to Topo IIα and point to a role of Fbxo28 in regulating chromosome morphology in order to ensure proper chromosome segregation in mitosis.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

Fbxo28 cDNA (IRATp970B0145D) was received from Imagenes (Berlin, Germany) PCR amplified and cloned into the XhoI–BamHI sites of pEGFP-C3 (Takara Bio Inc. Germany). To generate pEGFP-C3-Fbxo28, which lacks the F-box domain (aa 61–109) (pCMV-3Tag-1A-ΔFbxo28), 2 fragments were amplified via PCR from pCMV-3Tag1A-Fbxo28. Fragment 1 corresponding to 1–180 bp (BamHI/blunt end) and fragment 2 corresponding to 328–1107 bp (blunt end/XhoI), blunt end ligated, PCR-amplified and cloned into pEGFP-C3 via BamHI/XhoI sites. Fbxo28 siRNA resistant fragment was generated by Geneart (Darmstadt, Germany) and cloned into pEGFP-C3 via XhoI-KpnI. HA-tag was introduced N-terminal into pCMV-3Tag1A-Fbxo28 or pCMV-3Tag1A-ΔF-Box-Fbxo28 plasmid by PCR via BamHI/XhoI or into pCMV-3Tag1A (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) via BamHI/PstI. pCDNA3-puro-3xFlag-hTopo IIα was kindly provided and described in.32

Cell culture and synchronization

HEK293T or HeLa cells (ACC 635, DSMZ Braunschweig, Germany) were cultured in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) containing 4.5 g/l glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), HeLa (ATCC CCL-2) (D. Beach, Cold Spring Harbour) and U2OS (ATCC HTB-96) (A. Fry/E. Nigg, Basel) cells were cultured in DMEM containing 1.0 g/l glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C in 5% CO2.

HeLa GFP-α-tubulin/RFP-H2B cells (D. Gerlich, ETH Zürich) were cultured in DMEM 1 g/l glucose, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and 500 µg/ml G418 (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany) and 0.5 µg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich).

HeLa cells were arrested in mitosis by treatment with 100 ng/ml Nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h.

HeLa cells were used for cell cycle synchronization experiments as best sychronization rates could be obtained in this cell line. This cell line was also mainly used for immunfluorescence and live cell imaging experiments.

In U2OS cells both the nuclear localization of Fbxo28 and the mitotic defect in response to Fbxo28 siRNA confirmed the results that were observed in HeLa cells.

HEK293T cells were treated 5 h with 50 µM Apigenin (Sigma-Aldrich) or 2 h with 100 nM BI2536 (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany) for CK2 and Plk1 inhibition, respectively. HEK293T cells were used in transient transfection experiments because highest transfection rates could be obtained.

For the double thymidine block, cells were treated twice with 2 mM thymidine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h and released for 8 h in between.

Cells were arrested in mitosis by the addition of 2.5 mM thymidine for 22 h, subsequent release from the thymidine block for 6 h and treatment with 100 ng/ml Nocodazole (AppliChem) for 4 h.

Generation of stable HeLa S/A cell line for conditional Fbxo28 knockdown

HeLa S/A cells (O.Gruss, ZMBH, Heidelberg) were transiently co-transfected with the engineered recombination plasmid pBi-9 harboring Fbxo28 siFbox_2 miRNA sequence and the pCAGGS.Flpe vector (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA). One day after transfection (day 1) the cells were selected with puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) (5µg/ml) for cells carrying pCAGGS.Flpe vector. The following day (day 2) Ganciclovir (Alpha Diagnostic Intl. Inc., San Antonio, TX, USA) (10 µM) was added and cells positive for miRNA integration were selected for 4 d. Afterwards the media was changed against media without selective antibiotics (day 6) and cell clones were grown until colony formation. Finally surviving clones were picked and analyzed for integration by Western blotting after doxycycline (2 µg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) induction.

Generation of stable tet-inducible HeLa T-Rex-GFP-Fbxo28 cell line

GFP-Fbxo28 was cloned into pCDNA5-FRT vector (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) via HindIII and NotI. HeLa T-Rex cells (M. Lemberg, ZMBH, Heidelberg) were co-transfected with pCDNA5-FRT-GFP-Fbxo28 and pOG44 (Invitrogen) vector and selected with Hygromycin B (400 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich). Surviving clones were picked and analyzed for integration by Western blotting after doxycycline induction.

Plasmid and siRNA transfection

For siRNA transfections HeLa or U2OS cells were twice transfected with the indicated siRNA (10–100 nM final concentration) and with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HEK293T cells were transfected for 24 h with 10 µg plasmid DNA for 10 cm dish, or 20–27 µg plasmid DNA for 15 cm dish using polyethylenimine (Polysciences, Eppelheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

siRNAs were directed against the following sequences:

siFbxo28_2: 5′-GCUUUAUGUCCUACGACGAtt 3-; siFbxo28_3:

5′-GCUUUAUGUCCUACGACGAtt-3′; siFbxo28_1: published (17)

firefly luciferase Gl2 (control): 5′-CGUACGCGGAAUACUUUCGAtt-3′;

siFbxo28_2, siFbxo28_3 and Gl2 were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Darmstadt, Germany).

Antibodies

A rabbit anti-Fbxo28 antibody was raised against a synthetic peptide spanning residues 19–32 ((Ac-) DGGSSLASGSTQRQC (-CONH2)) of Fbxo28 (Innovagen, Sweden). The antibody was purified using the corresponding peptide immobilized on CNBr-activated Sepharose (Fbxo28 ab1).

Other antibodies used in this study: rabbit anti-Fbxo28 (A302–377A) (Fbxo28 ab2) and rabbit anti-Topo IIα (A300–054A) (Topo IIα ab1) were from Bethyl (Montgomery, TX, USA); rabbit anti-GFP (NB600–303, Novus, Abingdon, UK); rabbit-anti-Skp1 (sc-7163), mouse anti-Plk1 (F-8, sc-17783), mouse anti-cyclin E (HE12, sc-247), mouse anti-Topo IIα (A-8, sc-165986) (Topo IIα ab2) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, (Heidelberg, Germany); mouse anti-α-tubulin (T5168) and mouse anti-Flag M2 (F3165) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich; rabbit anti-KU80 (#2753) was purchased from Cell signaling (Leiden, Netherlands); mouse anti-BubR1 was from Babco (Richmond, CA, USA); mouse anti-Mad2 (PA5–2159) was from Thermo Scientific (Darmstadt, Germany). Secondary antibodies for Western blotting were peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) and goat anti-mouse (Novus). Secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence were goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes, Life Technology, Darmstadt, Germany).

In vitro decatenation assay

In vitro decatenation assay kit was purchased from Topogen (Port Orange, Florida, USA), and the assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Topo IIα extract preparation from HeLa S/A shFbxo28 cell lines was prepared from 1×10 cm dish per condition as suggested by the Topogen protocol.

Purification and analysis of Fbxo28 interacting proteins

HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-HA-Fbxo28, Flag-HA-ΔFbxo28 or Flag-HA-empty vector as control and incubated for 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared with NP40 lysis buffer (40 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitors) and pre-cleared with Sepharose beads CL-4B (Amersham Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C. Fbxo28 was immunopurified with anti-Flag M2 affinity beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were washed 3–4 times with NP40 buffer and eluted by competition with 3xFlag-peptide (Sigma-Aldrich) (500 ng/µl). The eluate was then subjected to a second immunopurification over night with an anti-HA resin (Sigma-Aldrich), before elution by competition with HA-peptide (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The eluate was then subjected to an acetone precipitation, boiled in sample buffer. 2% of the Flag-elution and 5% of HA-elution were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, performed according to a standard protocol.33

The other samples were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by colloidal blue staining and sent for mass spectrometry analysis.

Mass spectrometry analysis

For identification of Flag-HA-Fbxo28 interacting proteins, Flag-HA-ΔFbxo28 immunoprecipitates were prepared as described above, resolved by SDS-PAGE following colloidal blue staining. The gel lanes were cut into slices, digested with trypsin after reduction and alkylation of cystines. Tryptic peptides were analyzed by nanoLC-ESI-MS/MS using a nanoAcquity UPLC system (Waters GmbH, Eschborn, Germany) coupled online to an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Data were acquired by scan cycles of one FTMS scan with a resolution of 60000 at m/z 400 and a range from 300 to 2000 m/z in parallel with 6 MS/MS scans in the ion trap of the most abundant precursor ions. Instrument control, data acquisition and peak integration were performed using the Xcalibur software 2.1 (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Database searches were performed against the SwissProt database with taxonomy “human” using the MASCOT search engine (Matrix Science, London, UK; version 2.2.2). MS/MS files from the individual gel slices of each lane were merged into a single search. Peptide mass tolerance for database searches was set to 5 ppm and fragment mass tolerance was set to 0.4 Da. Significance threshold was p < 0.01. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set as fixed modification. Variable modifications included oxidation of methionine and deamidation of asparagine and glutamine. One missed cleavage site in case of incomplete trypsin hydrolysis was allowed.

Immunofluorescence microscopy and live-cell imaging

For immunofluorescence staining, cells grown on coverslips were treated with PEM (100 mM Pipes pH 6.8, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.2% Triton X-100) for 50 sec, fixed for 10 min with 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature, treated with 0.5% SDS for 1 min, permeabilized 10 min with PBS/0.2% Triton X-100 and blocked with 3% BSA/PBS for 20–30 min. Alternatively, cells grown on coverslips were fixed with −20°C methanol for 8 min, washed with PBS and blocked with 3% BSA/PBS for 20–30 min. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 3% BSA/PBS for 1–2 h, then washed 3x with PBS, and incubated with secondary antibodies and 1 µg/ml Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen) for 1 h. After washing for 3 times with PBS, coverslips were mounted onto glass slides with ProLong Gold (Molecular Probes).

For cell imaging, the Zeiss motorized inverted Observer Z1 microscope was used, containing mercury arc burner HXP 120 C and LED module Colibri. Filter combinations: GFP (38 HE) DsRed (43 HE) and DAPI (49) with the AxioCam MR3 camera system and a 63 × /1.4 Oil Pln Apo DICII objective. Alternatively, images were obtained with a Zeiss LSM700 upright motorized confocal microscope with a 63x NA 1.4 oil immersion objective. Images were then processed with Image J (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij) to produce the figures.

For live cell imaging experiments HeLa GFP-α-tubulin/RFP-H2B cells were blocked by a double thymidine block, together with a double siRNA transfection. After the second thymidine release, 2.5 × 104 cells were seeded per Ibidi dish chamber. The cells were monitored by a 20x/0.4 LD PlnN PH2 DICII objective on an inverted microscope (Zeiss motorized Observer.Z1) connected to a AxioCam MR3 camera system at 5% CO2 and 37°C. LED module Colibri.2 with 470 nm for GFP and 590 nm for RFP were used for fluorochrome excitation. Multi-point images were taken with 5 z-stacks spaced 2 µm apart every 3 min for 10 or 12 h by Cell Zeiss ZEN blue software. Maximum intensity projection of the fluorescent channels and background subtraction was performed by ImageJ software to create 8-bit RGB TIFF files and movies.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Cell lysates were prepared with NP-40 lysis buffer following short sonification (Bioruptor, diagenode) or with Triton X-100 buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitors). For endogenous Topo IIα or Fbxo28 immunoprecipiations, lysates were prepared with TEMP extraction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM PMSF) according to the TopoGEN protocol. For co-immunoprecipitations 1–6 mg of cell lysate were incubated with 1–6 µg of specific antibodies in lysis buffer for 2 h or overnight at 4°C on a rotating wheel. Incubation of normal mouse/ or rabbit IgGs (Santa Cruz) was done as control. Protein G or Protein A beads (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany) were added for 1–4 h, followed by 3 to 4 times washing with lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitated proteins were boiled at 95°C for 10 min in 4 × SDS buffer and finally analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Immunoreactive signals were detected with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany).

In vivo ubiquitylation assay

HeLa S/A shFbxo28 cells were induced with doxycycline for 48 h and transfected with HA-ubiquitin plasmid for 24 h. Before harvesting, cells were treated with 10 µM MG132 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 h. Cells were scratched off the plate, washed twice with PBS and cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.25 M NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4). Protease inhibitors and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM, 10 mM) (Sigma-Aldrich) were freshly added to the lysis buffer and cells were lysed 30 min at 4°C. Endogenous Topo IIα was immunoprecipitated for 2 h at 4°C with additional 0.1% SDS added to the lysis buffer. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred over night by wet blotting to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was denatured for 30 min at 4°C in Western blot denaturing Buffer (6 M guanidine-HCL, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF) and washed for several times with PBS before ubiquitin was detected with a HA-antibody.

In vitro kinase assay

1 μg of GST-tag alone or GST-Fbxo28 purified from E. coli were incubated with 150 U or 500 U recombinant CK2 (NEB), isolated from E. coli, in a 30 μl reaction volume with NEBuffer for Protein Kinases (NEB) supplemented with 33 μM ATP and 5 μCi [γ-32P]-ATP for 30 min at 30°C. The samples were then boiled with sample buffer for 5 min at 95°C and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, coomassie staining and autoradiography.

Chromosome spreads

HeLa S/A shFbxo28 cells were treated with 2 µg/ml doxycycline for 72 h to induce expression of Fbxo28 shRNA. The cells were then treated with 0.1 μg/ml colchicine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h to induce metaphase arrest before harvesting by trypsinization. The cells were incubated in 75 mM KCl hypotonic buffer for 10 min at 37°C, fixed by methanol: glacial acetic acid (3:1), dropped onto cold glass slides and stained by 5% Giemsa (Roth) in water. Digital images were captured using the Zeiss motorized inverted Observer Z1 microscope equipped with color CCD camera AxioCam ICc 3 and a 63×/1.4 Oil Pln Apo DICII objective and analyzed by using the ImageJ software.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge C. Farr, O. Gruss, D. Gerlich, M. Lemberg for providing reagents. The members of our lab are thanked for comments and critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Krebshilfe (grant no 110924) and the DKFZ PhD program.

References

- [1].Chen SH, Chan NL, Hsieh TS. New mechanistic and functional insights into DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem 2013; 82:139-70; PMID:23495937; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-100002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Heck MM, Hittelman WN, Earnshaw WC. Differential expression of DNA topoisomerases I and II during the eukaryotic cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988; 85:1086-90; PMID:2829215; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ishida R, Sato M, Narita T, Utsumi KR, Nishimoto T, Morita T, Nagata H, Andoh T. Inhibition of DNA topoisomerase II by ICRF-193 induces polyploidization by uncoupling chromosome dynamics from other cell cycle events. J Cell Biol 1994; 126:1341-51; PMID:8089169; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oliveira RA, Hamilton RS, Pauli A, Davis I, Nasmyth K. Cohesin cleavage and Cdk inhibition trigger formation of daughter nuclei. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12:185-92; PMID:20081838; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Holm C, Goto T, Wang JC, Botstein D. DNA topoisomerase II is required at the time of mitosis in yeast. Cell 1985; 41:553-63; PMID:2985283; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(85)80028-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Uemura T, Ohkura H, Adachi Y, Morino K, Shiozaki K, Yanagida M. DNA topoisomerase II is required for condensation and separation of mitotic chromosomes in S. pombe. Cell 1987; 50:917-25; PMID:3040264; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90518-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kato J, Nishimura Y, Imamura R, Niki H, Hiraga S, Suzuki H. New topoisomerase essential for chromosome segregation in E. coli. Cell 1990; 63:393-404; PMID:2170028; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90172-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Downes CS, Clarke DJ, Mullinger AM, Gimenez-Abian JF, Creighton AM, Johnson RT. A topoisomerase II-dependent G2 cycle checkpoint in mammalian cells. Nature 1994; 372:467-70; PMID:7984241; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/372467a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Deming PB, Cistulli CA, Zhao H, Graves PR, Piwnica-Worms H, Paules RS, Downes CS, Kaufmann WK. The human decatenation checkpoint. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98:12044-9; PMID:11593014; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.221430898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lou Z, Minter-Dykhouse K, Chen J. BRCA1 participates in DNA decatenation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005; 12:589-93; PMID:15965487; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li H, Wang Y, Liu X. Plk1-dependent phosphorylation regulates functions of DNA topoisomerase IIalpha in cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:6209-21; PMID:18171681; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M709007200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ackerman P, Glover CV, Osheroff N. Phosphorylation of DNA topoisomerase II by casein kinase II: modulation of eukaryotic topoisomerase II activity in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1985; 82:3164-8; PMID:2987912; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Komander D, Rape M. The ubiquitin code. Annu Rev Biochem 2012; 81:203-29; PMID:22524316; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Skaar JR, Pagan JK, Pagano M. SCF ubiquitin ligase-targeted therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014; 13:889-903; PMID:25394868; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrd4432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zimmerman ES, Schulman BA, Zheng N. Structural assembly of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2010; 20:714-21; PMID:20880695; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zheng N, Schulman BA, Song L, Miller JJ, Jeffrey PD, Wang P, Chu C, Koepp DM, Elledge SJ, Pagano M, et al.. Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 2002; 416:703-9; PMID:11961546; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/416703a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schulman BA, Carrano AC, Jeffrey PD, Bowen Z, Kinnucan ER, Finnin MS, Elledge SJ, Harper JW, Pagano M, Pavletich NP. Insights into SCF ubiquitin ligases from the structure of the Skp1-Skp2 complex. Nature 2000; 408:381-6; PMID:11099048; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35042620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Welcker M, Clurman BE. FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: a tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division, growth and differentiation. Nat Rev Cancer 2008; 8:83-93; PMID:18094723; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cizmecioglu O, Krause A, Bahtz R, Ehret L, Malek N, Hoffmann I. Plk2 regulates centriole duplication through phosphorylation-mediated degradation of Fbxw7 (human Cdc4). J Cell Sci 2012; 125:981-92; PMID:22399798; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.095075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nelson DE, Randle SJ, Laman H. Beyond ubiquitination: the atypical functions of Fbxo7 and other F-box proteins. Open Biol 2013; 3:130131; PMID:24107298; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rsob.130131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cepeda D, Ng HF, Sharifi HR, Mahmoudi S, Cerrato VS, Fredlund E, Magnusson K, Nilsson H, Malyukova A, Rantala J, et al.. CDK-mediated activation of the SCF(FBXO) (28) ubiquitin ligase promotes MYC-driven transcription and tumourigenesis and predicts poor survival in breast cancer. EMBO Mol Med 2013; 5:999-1018; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/emmm.201202341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ferrandon D. Ubiquitin-proteasome: pallbearer carries the deceased to the grave. Immunity 2007; 27:541-4; PMID:17967407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xiao H, Wang H, Silva EA, Thompson J, Guillou A, Yates JR Jr, Buchon N, Franc NC. The Pallbearer E3 ligase promotes actin remodeling via RAC in efferocytosis by degrading the ribosomal protein S6. Dev Cell 2015; 32:19-30; PMID:25533207; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Musacchio A, Salmon ED. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007; 8:379-93; PMID:17426725; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gallego-Paez LM, Tanaka H, Bando M, Takahashi M, Nozaki N, Nakato R, Shirahige K, Hirota T. Smc5/6-mediated regulation of replication progression contributes to chromosome assembly during mitosis in human cells. Mol Biol Cell 2014; 25:302-17; PMID:24258023; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E13-01-0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Li Y, Ozaki T, Kikuchi H, Yamamoto H, Ohira M, Nakagawara A. A novel HECT-type E3 ubiquitin protein ligase NEDL1 enhances the p53-mediated apoptotic cell death in its catalytic activity-independent manner. Oncogene 2008; 27:3700-9; PMID:18223681; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1211032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lolli G, Cozza G, Mazzorana M, Tibaldi E, Cesaro L, Donella-Deana A, Meggio F, Venerando A, Franchin C, Sarno S, et al.. Inhibition of protein kinase CK2 by flavonoids and tyrphostins. A structural insight. Biochemistry 2012; 51:6097-107; PMID:22794353; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi300531c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jonkers W, Rep M. Lessons from fungal F-box proteins. Eukaryot Cell 2009; 8:677-95; PMID:19286981; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/EC.00386-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Krauss SW, Spence JR, Bahmanyar S, Barth AI, Go MM, Czerwinski D, Meyer AJ. Downregulation of protein 4.1R, a mature centriole protein, disrupts centrosomes, alters cell cycle progression, and perturbs mitotic spindles and anaphase. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28:2283-94; PMID:18212055; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.02021-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Logarinho E, Maffini S, Barisic M, Marques A, Toso A, Meraldi P, Maiato H. CLASPs prevent irreversible multipolarity by ensuring spindle-pole resistance to traction forces during chromosome alignment. Nat Cell Biol 2012; 14:295-303; PMID:22307330; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Maiato H, Logarinho E. Mitotic spindle multipolarity without centrosome amplification. Nat Cell Biol 2014; 16:386-94; PMID:24914434; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Farr CJ, Antoniou-Kourounioti M, Mimmack ML, Volkov A, Porter AC. The α isoform of topoisomerase II is required for hypercompaction of mitotic chromosomes in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42:4414-26; PMID:24476913; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gku076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hassepass I, Voit R, Hoffmann I. Phosphorylation at serine 75 is required for UV-mediated degradation of human Cdc25A phosphatase at the S-phase checkpoint. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:29824-9; PMID:12759351; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M302704200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.